Lymphangiomatosis

Lymphangiomatosis is a benign overgrowth (proliferation) of lymphatic vessels 1. There is a lack of consensus among the medical community as to the proper terminology for disorders and malformations associated with lymphatics. Lymphangiomatosis literally means lymphatic vessel tumor or cyst condition 2. Lymphangiomatosis is a multisystemic disorder, characterized by congenital malformation of the lymphatic system with channels and presence of cysts that result from an increase both in the size and number of thin-walled lymphatic channels that are abnormally interconnected and dilated 1. Lymphangiectasis refers to dilatation of lymphatics. Lymphangiomas are a relatively localized collection of abnormal lymphatic vessels, composed of multiple dilated lymphatic channels lined by endothelial cells. There are very rare reports of cases with multiple lymphangiomas 3. In some patients there is overlap between these and so exact classification becomes problematic. Lymphangiomatosis may involve a single organ system; 75% of cases involve multiple organs and can occur anywhere in the body including abdominal lymphangiomatosis where it involves the mesentery, omentum, mesocolon and retroperitoneum 4. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract may be affected, but the incidence in the intestinal wall is very low 5. In the few cases described in the literature, the symptomatology was characterized mainly by abdominal pain and bleeding. Aggressive surgery should be avoided in asymptomatic cases, because it is now known that these lesions are benign 6.

The lymphatic system is part of your immune system made up of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, the small nodules where certain white blood cells (lymphocytes) and other cells that participate in the immune regulatory system of your body that help to protect your body from infection and foreign substances. Lymphatic vessels reach every part of the body except the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord), which has its own specialized system. The lymphatic system has three main functions:

- to maintain fluid balance,

- to defend the body against disease by producing lymphocytes, and

- to absorb fats and fat soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) from the small intestine and transport them to the blood, bypassing the liver.

When fluid leaves arteries and enters the soft tissue and organs of the body, it does so without red or white blood cells. This thin watery fluid is known as lymph. The lymphatic system consists of a network of tubular channels (lymph vessels) that transport lymph back into the bloodstream. Lymph accumulates between tissue cells and contains proteins, fats, and lymphocytes. As lymph moves through the lymphatic system, it passes through the network of lymph nodes that help the body to deactivate sources of infection (e.g., viruses, bacteria, etc.) and other potentially injurious substances and toxins. Groups of lymph nodes are located throughout the body, including in the neck, under the arms (axillae), at the elbows, and in the chest, abdomen, and groin. The lymphatic system also includes the spleen, which filters worn-out red blood cells and produces lymphocytes; and bone marrow, which is the spongy tissue inside the cavities of bones that manufactures blood cells.

Lymphangiomatosis is generally considered as congenital malformation of the lymphatic system associated with alterations in the circulatory dynamics of the lymph 6. Lymphangiomatosis, like other lymphatic malformations, is thought to be the result of congenital errors of lymphatic development occurring prior to the 20th week of gestation 4. Lymphangiomatosis may also occur in association with better-characterized disease such as Gorham’s disease. Gorham’s disease is a form of lymphangiomatosis in which the lymphatics proliferate in bone, resulting in progressive bone loss. Another disease, which has a similar sounding name, is Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), a distinct disorder caused by proliferation of smooth muscle-like cells that, despite the similarity in the names, is unrelated to lymphangiomatosis. LAM occurs almost exclusively in women, while lymphangiomatosis is not as gender restricted.

Lymphangiomatosis can occur at any age, but the incidence is highest in children and teenagers, typically presenting by age 20 and, although it is technically benign, these deranged lymphatics tend to invade surrounding tissues and cause problems due to invasion and/or compression of adjacent structures 7. Lymphangiomatosis affects males and females of all races and exhibits no inheritance pattern. Because it is so rare, and commonly misdiagnosed, it is not known exactly how many people are affected by lymphangiomatosis. Lymphangiomatosis is most common in the bones and lung 4 and shares some characteristics with Gorham’s disease. Up to 75% of patients with lymphangiomatosis have bone involvement, leading some to conclude that lymphangiomatosis and Gorham’s disease should be considered as a spectrum of disease rather than separate diseases 8. When it occurs in the lungs, lymphangiomatosis has serious consequences and is most aggressive in the youngest children 9. When lymphangiomatosis extends into the chest it commonly results in the accumulation of chyle in the linings of the heart and/or lungs 4. Chyle is composed of lymph fluid and fats that are absorbed from the small intestine by specialized lymphatic vessels called lacteals during digestion. The accumulations are described based on location: chylothorax is chyle in the chest; chylopericardium is chyle trapped inside the sack surrounding the heart; chyloascites is chyle trapped in the linings of the abdomen and abdominal organs. The presence of chyle in these places accounts for many of the symptoms and complications associated with both lymphangiomatosis and Gorham’s disease 10. The incidence of lymphangiomatosis is unknown and it is often misdiagnosed. It is separate and distinct from lymphangiectasis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma 9. Its unusual nature makes lymphangiomatosis (and Gorham’s disease) a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge 11. A multidisciplinary approach is generally necessary for optimal diagnosis and symptom management.

Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis

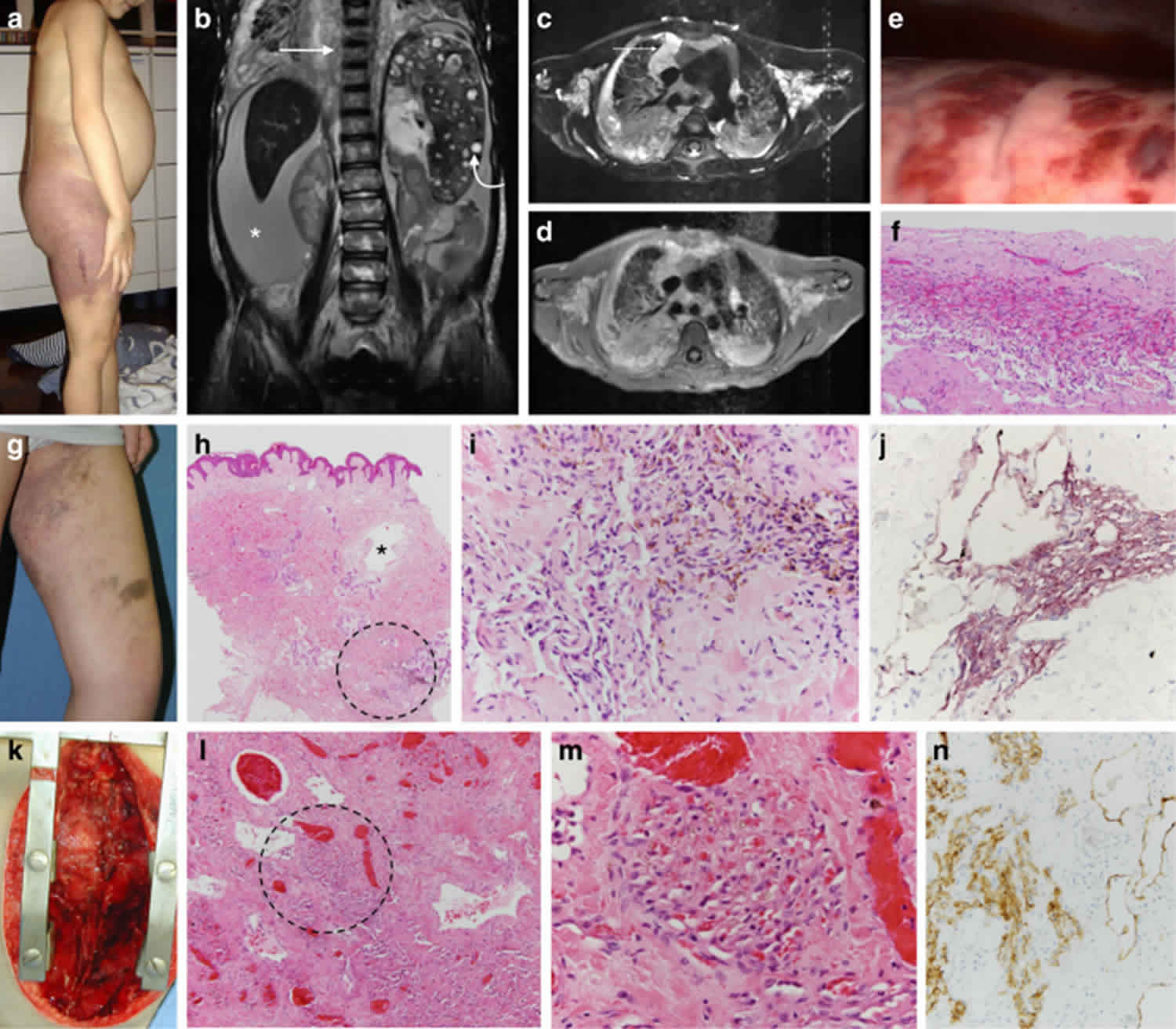

Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis is a rare lymphatic system abnormality associated with a poor prognosis 12. Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis involves multiple parts of the body, especially the lungs and chest. The hallmarks of kaposiform lymphangiomatosis include multifocal, intra- and extra-thoracic lymphatic malformations, thrombocytopenia and consumptive coagulopathy 13.

Symptoms of kaposiform lymphangiomatosis usually start during childhood, and include shortness of breath (dyspnea) and cough due to the accumulation of fluid around the lungs (pleural effusion) and heart (pericardial effusion). Other common symptoms include chest and body pain, abnormal bleeding and bruising, and soft masses under the skin. Blood collections may form under the skull (epidural hematoma) 12.

The exact prevalence and incidence of kaposiform lymphangiomatosis is unknown, but the disease is very rare. Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis usually presents at birth or early childhood, however reports exist of disease manifestations later in life 12. Males and females appear equally affected.

The exact cause of kaposiform lymphangiomatosis is unknown, however genetic factors and changes in utero are thought to contribute to disease development and it is not thought to be inherited in families.

Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis is diagnosed based on the symptoms, laboratory testing, and a biopsy of tumor tissue 14. There is no specific treatment for kaposiform lymphangiomatosis. Treatment is based on the symptoms and treatment options may include surgical procedures to drain excess fluid and reduce the size of masses, chemotherapy medications and steroids. Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis prognosis is generally poor as the disease is progressive despite medical intervention. Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis tends to be a progressive condition that gets worse with time. The most serious complications include the build-up of fluid around the lungs and heart, and the risk for abnormal bleeding 15.

Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis causes

The cause of kaposiform lymphangiomatosis is unknown. Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis is the result of an abnormality in formation of the lymph system during fetal development 12.

Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis symptoms

The symptoms of kaposiform lymphangiomatosis may be different from person to person. Some people may be more severely affected than others, and some people may develop symptoms at later ages than others. Symptoms usually begin in childhood and typically include 15:

- Difficulty breathing (dyspnea)

- Cough

- Abnormal bleeding due to low platelet count (thrombocytopenia)

- Bruising

- Mass under the skin

Other symptoms may include bony changes due to bone tissue destruction and fever. A few people with kaposiform lymphangiomatosis did not have symptoms until adulthood 16.

Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis diagnosis

The diagnosis of kaposiform lymphangiomatosis is based on the symptoms and the distinct features of the tumors formed in kaposiform lymphangiomatosis 17. A small sample of tumor tissue examined under a microscope (biopsy) can help confirm the diagnosis. Tumor genetic testing may also show specific genetic changes that can help with the diagnosis 14.

Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis treatment

There is no specific treatment for kaposiform lymphangiomatosis, but patients are treated with a combination of medical and surgical therapies. Treatment is based on managing the symptoms and controlling the growth of abnormal lymph vessels. Medical therapies may include combinations of steroids, chemotherapy and immunomodulators (inferferon, siolimus, vincristine) but responses are unpredictable 18. Surgical procedures are usually for symptomatic benefit and may include surgical procedures to drain excess fluid; however splenectomy appears beneficial in some patients for refractory thrombocytopenia.

Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis prognosis

The duration and outcome of a rare disease like kaposiform lymphangiomatosis is influenced by many factors. These include the severity of the symptoms, the availability of treatment, other medical conditions and lifestyle factors.

People with kaposiform lymphangiomatosis may begin to have symptoms in childhood. The first symptoms may include a dry cough and body pain. Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis is a progressive condition that gets worse over time. Some of the symptoms such as the build-up of fluid around the lungs and heart and abnormal bleeding may be life threatening.

The 5-year survival for kaposiform lymphangiomatosis was 51%; overall survival was 34% 19. The cause of death in most instances was cardio-respiratory failure. Mean interval between diagnosis and death was 2.75 years (range, 1.1 to 6.5 years) 19. Outcome for survivors varied; median follow-up was 2.5 years. Three patients continue on pharmacotherapy. Two patients, off treatment for more than 10 years, reported chronic musculoskeletal pain as a prominent, long-term issue. Only one of these patients had major respiratory symptoms; the other had cutaneous staining and functional limitation in the affected extremity prior to therapy. One patient, who presented as an adult, never required intervention and denied any problems 19.

Pulmonary lymphangiomatosis

Pulmonary lymphangiomatosis also called diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis, is a disease in which the overgrowth (proliferation) of lymphatic vessels (lymphangiomatosis) occurs in the lungs, pleura and typically the surrounding soft tissue of the chest (mediastinum) 20.

Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis affects males and females in equal numbers. Most cases have been reported infants and children, but the disorder has occurred in adults as well. The disorder has been reported in individuals of every race and ethnicity. The exact incidence or prevalence is unknown. Pulmonary lymphangiomatosis often goes misdiagnosed or undiagnosed, making it difficult to determine true frequency of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis in the general population.

Pulmonary lymphangiomatosis causes

The exact cause of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis is unknown. Lymphangiomatosis in general is believed to result from abnormalities in the development of the lymphatic vascular system during embryonic growth. No environmental, immunological or genetic risk factors that may play a role in the development of the disorder have been identified.

The symptoms of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis are caused by complications due to the overproduction (proliferation), widening (dilation), and thickening of lymphatic vessels throughout the lungs.

Researchers are studying whether vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3) plays a role in the development of lymphangiomatosis. Researchers have determined that affected tissue in individuals with lymphangiomatosis have high levels of VEGFR-3, a chemical that most likely promotes the growth of lymphatic vessels. A better understanding of such underlying mechanisms should lead to targeted therapies for individuals with lymphangiomatosis.

Pulmonary lymphangiomatosis symptoms

The symptoms and severity of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis can vary from one person to another and there is no typical or standard presentation for the disorder. Generally, pulmonary lymphangiomatosis progresses faster in children than adults. Some individuals may eventually experience life-threatening complications, while others have mild symptoms that can go undiagnosed well until adulthood. Consequently, it is important to note that one person’s experience can vary dramatically from another’s. Affected individuals and parents of affected children should talk to their physician and medical team about their specific case, associated symptoms and overall prognosis.

The specific symptoms associated with diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis depend upon the size and exact location of affected lymphatic vessels. The disorder often causes a variety of general, nonspecific symptoms including fatigue and nausea as well as symptoms more directly related to the chest, including chest pain, wheezing, shortness of breath (dyspnea), chronic cough, and coughing up blood (hemoptysis). Chest tightness, recurrent respiratory infections and recurrent pneumonia have also been reported in individuals with diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Some individuals give a history of asthma but the symptoms may actually be secondary to the lymphangiomatosis rather than true asthma.

Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis can eventually cause compression of nearby structures in the chest, bony destruction leading to the appearance of “holes” in adjacent bones (lytic bone lesions), and other complications such as the accumulation of lymph fluid (chyle) in the space between the lung surface and chest wall (pleural space), a condition known as chylous pleural effusions. A collapsed lung (pneumothorax) can also occur. Some of these complications can be life-threatening e.g. when chylous pleural effusions become large enough to make breathing difficult, and when chyle accumulates in the sac around the heart (pericardial effusion) and makes it difficult for the heart to pump blood. The excess fluid in the lungs and other spaces also can lead to severe infection, as bacteria can rest in these excess fluid pockets.

Pulmonary lymphangiomatosis diagnosis

A diagnosis of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis is based upon identification of characteristic symptoms, a detailed patient history, a thorough clinical evaluation, and a variety of specialized tests. Because of the disorder’s rarity and varying presentation in each individual, obtaining a correct diagnosis can be challenging.

Clinical testing and workup

Pulmonary function tests may be used to help diagnose diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. This group of tests can evaluate how well the lungs are functioning. Affected individuals often have a restrictive pattern or a mixed restrictive and obstructive pattern of lung function.

Lymphoscintigraphy is a specialized procedure in which small amounts of radioactive material is used to help create pictures (called scintigrams) of the lymphatic system. Lymphoscintigraphy is used to help obtain a diagnosis of lymphatic disease and/or to assess the extent of the disease.

Surgical removal and microscopic examination of affected lung tissue (lung biopsy) may be used to confirm a diagnosis of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. However, a lung biopsy is not always possible and can be associated with complications such as the accumulation of chyle within the thoracic cavity and around the lungs (chylothorax). If an area of bone is affected, a bone biopsy may be performed.

Various imaging techniques including plain x-rays, ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to determine the location, behavior and extent of the disorder. Plain x-rays can reveal snow-white patches (infiltrates) or chylous effusions. During and ultrasound, high-frequency radio waves are used to create a picture of internal organs. During CT scanning, a computer and x-rays are used to create a film showing cross-sectional images of certain tissue structures. An MRI uses a magnetic field and radio waves to produce cross-sectional images of particular organs and bodily tissues.

Pulmonary lymphangiomatosis treatment

No specific treatment for diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis is universally accepted. Current therapies are supportive and essentially palliative, aiming to relieve clinical symptoms that are apparent in each individual 21. Treatment may require the coordinated efforts of a team of specialists. Pediatricians, surgeons, pulmonologists, radiologists, and other healthcare professionals may need to systematically and comprehensively plan effective treatment. In extremely rare cases, spontaneous remission, in which symptoms go away on their own, has been reported.

Specific therapeutic procedures and interventions may vary, depending upon numerous factors, such as disease severity; the size and location of the lymphatic abnormalities; the presence or absence of certain symptoms; an individual’s age and general health; and/or other elements. Decisions concerning the use of particular drug regimens and/or other treatments should be made by physicians and other members of the health care team in careful consultation with the patient or parents based upon the specifics of the case; a thorough discussion of the potential benefits and risks, including possible side effects and long-term effects; patient preference; and other appropriate factors.

A wide variety of potential therapies have been tried in individuals with diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. There are no standardized treatment protocols or guidelines for affected individuals. Due to the rarity of the disease, there are no treatment trials that have been tested on a large group of patients. Various treatments have been reported in the medical literature as part of single case reports or small series of patients. Treatment trials would be very helpful to determine the long-term safety and effectiveness of specific medications and treatments for individuals with diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis.

Surgical removal (excision) of affected tissue can be performed and has been effective in some cases when the disease is more localized. However, this is typically not the case in diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. When surgery is attempted, diseased lymphatic tissue is often difficult to distinguish from healthy tissue, making it challenging to completely remove all affected tissue. Any diseased tissue left behind can cause recurrence of the disorder. In addition, it may be impossible to remove all of the diseased lymphatic tissue because of its location near or around vital organs.

Sclerotherapy is a procedure in which a solution, called a sclerosant or sclerosing agent, is injected directly into the lesion. This solution causes scarring within the lesion, eventually causing it to shrink or collapse. In most cases, the antibiotic doxycycline is the sclerosing agent used. Sclerotherapy may require multiple sessions to be effective and has demonstrated good results in some cases. Again, however, this is of limited value in a widespread disease such as diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis,but could for example be used to partially treat pleural effusions, or the build-up of chyle in the space between the lungs and chest wall.

A variety of drugs have been reported in the medical literature for the treatment of individuals with diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Two commonly used drugs are interferon alfa 2b and glucocorticoids. Other medications that have been tried include bisphosphates, thalidomide, and rapamycin. Recently, researchers have reported encouraging results with drugs that inhibit, either directly or indirectly, the production of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3), specifically the drugs propranolol and bevacizumab.

Radiotherapy, or the use of radiation to destroy affected tissue, has also been tried in individuals with diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis where surgery is not an option.

Some individuals have been treated by dietary adjustments such as restricting fat, except for a particular type of fat known as medium chain triglycerides. Dietary treatments, however, have generally proven ineffective. Drainage of fluid around lungs and heart may be necessary in some cases (pleural or pericardial drainage). Some individuals have also undergone artificial destruction of the pleural space (pleurodesis) to prevent fluid accumulation there. Surgical removal of part of the pleura has also been tried (pleurectomy). Lung transplantation has been used to treat some patients with severe disease that has not responded to any other therapy, but due to the extensive nature of the disease in the chest, this surgery can be very challenging.

Are there dietary recommendations for infants with pulmonary lymphangiomatosis?

There is no published dietary guidelines for infants with pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Conservative treatment options such as total parenteral nutrition (TPN), medium chain triglyceride (MCTG), and high protein diet appear to be ineffective 22.

Lymphangiomatosis causes

The cause of lymphangiomatosis is not yet known. As stated earlier, it is generally considered to be the result of congenital errors of lymphatic development occurring prior to the 20th week of gestation 7. Because of the overlap in involved systems, appearance of the diseases on imaging, and the presence of a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) some have concluded that lymphangiomatosis and Gorham’s disease should be considered as two forms of a single disease rather than two distinct conditions 23. However, the root causes of these conditions remains unknown and further research is necessary.

Lymphangiomatosis symptoms

Lymphangiomatosis is a multi-system disorder. Symptoms depend on the organ system involved and, to varying degrees, the extent of the disease. Early in the course of the disease patients are usually asymptomatic, but over time the abnormally proliferating lymphatic channels that constitute lymphangiomatosis are capable of massive expansion and infiltration into surrounding tissues, bone, and organs 7. Because of its slow course and often vague symptoms, the condition is frequently under-recognized or misdiagnosed 24.

Early signs of disease in the chest include wheezing, cough, and feeling short of breath, which is often misdiagnosed as asthma 4. The pain that accompanies bone involvement may be attributed to “growing pains” in younger children. With bone involvement the first indication for disease may be a pathological fracture. Symptoms may not raise concern, or even be noted, until the disease process has advanced to a point where it causes restrictive compression of vital structures 7. Furthermore, the occurrence of chylous effusions seems to be unrelated to the pathologic “burden” of the disease, the extent of involvement in any particular tissue or organ, or the age of the patient 25. This offers one explanation as to why, unfortunately, the appearance of chylous effusions in the chest or abdomen may be the first evidence of the disease.

Following are some of the commonly reported symptoms of lymphangiomatosis, divided into the regions or systems in which the disease occurs:

- Cardiothoracic region – Symptoms that arise from disease of the cardiothoracic region include a chronic cough, wheezing, dyspnea (shortness of breath)—especially serious when occurring at rest or when lying down—fever, chest pain, rapid heartbeat, dizziness, anxiety, and coughing up blood or chyle 4. As the deranged lymphatic vessels invade the organs and tissues in the chest they put stress on the heart and lungs, interfering with their ability to function normally. Additionally, these lymphatic vessels may leak, allowing fluid to accumulate in the chest, which puts further pressure on the vital organs, thus increasing their inability to function properly 7. Accumulations of fluid and chyle are named based on their contents and location: pulmonary edema (the presence of fluid and/or chyle in the lung), pleural effusions (fluid in the lung lining), pericardial effusions (fluid in the heart sack), chylothorax (chyle in the pleural cavity); and chylopericardium (chyle in the heart sack).

- Abdomen – Lymphangiomatosis has been reported in every region of the abdomen, though the most reported sites involve the intestines and peritoneum; spleen, kidneys, and liver. Often there are no symptoms until late in the progression of the disease. When they do occur, symptoms include abdominal pain and/or distension; nausea, vomiting, diarrhea; decreased appetite and malnourishment. When the disease affects the kidneys the symptoms include flank pain, abdominal distension, blood in the urine, and, possibly, elevated blood pressure, which may result in it being confused with other cystic renal disease.11 When lymphangiomatosis occurs in the liver and/or spleen it may be confused with polycystic liver disease 26. Symptoms may include abdominal fullness and distension; anemia, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), fluid accumulation in the abdomen(ascites), decreased appetite, weight loss, fatigue; late findings include liver failure 27.

- Skeletal system – Symptoms of lymphangiomatosis in the skeletal system are the same as those of Gorham’s disease. Frequently asymptomatic, skeletal lymphangiomatosis may be discovered incidentally or when a pathological fracture occurs. Patients may experience pain of varying severity in areas around the effected bone. When the disease occurs in the bones of the spine, neurological symptoms such as numbness and tingling may occur due to spinal nerve compression 28. Progression of disease in the spine may lead to paralysis. Lymphangiomatosis in conjunction with Chiari 1 malformation also has been reported 29.

Lymphangiomatosis diagnosis

Because lymphangiomatosis is rare and has a wide spectrum of clinical, histological, and imaging features, diagnosing lymphangiomatosis can be challenging 30. Plain x-rays reveal the presence of lytic lesions in bones, pathological fractures, interstitial infiltrates in the lungs, and chylous effusions that may be present even when there are no outward symptoms 11.

The most common locations of lymphangiomatosis are the lungs and bones and one important diagnostic clue is the coexistence of lytic bone lesions and chylous effusion 4. An isolated presentation usually carries a better prognosis than does multi-organ involvement; the combination of pleural and peritoneal involvement with chylous effusions and lytic bone lesions carries the least favorable prognosis 31.

When lung involvement is suspected, high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans may reveal a diffuse liquid-like infiltration in the mediastinal and hilar soft tissue, resulting from diffuse proliferation of lymphatic channels and accumulation of lymphatic fluid; diffuse peribronchovascular and interlobular septal thickening; ground-glass opacities; and pleural effusion 32. Pulmonary function testing reveals either restrictive pattern or a mixed obstructive/restrictive pattern 4. While x-rays, HRCT scan, MRI, ultrasound, lymphangiography, bone scan, and bronchoscopy all can have a roll in identifying lymphangiomatosis, biopsy remains the definitive diagnostic tool 32. However, there are reports of biopsy resulting in serious complications, such as chylothorax 33.

Microscopic examination of biopsy specimens reveals an increase in both the size and number of thin walled lymphatic channels along with lymphatic spaces that are interconnecting and dilated, lined by a single attenuated layer of endothelial cells involving the dermis, subcutis, and possibly underlying fascia and skeletal muscle 34. The histological features of the lymphangiomatosis are non-specific, and the definitive diagnosis requires the demonstration of an hyperproliferation of normal lymphatic vessels with normal endothelium, predominantly in the context of submucosa, with disruption of the muscular layer and sometimes of the serosa 1. Additionally, Tazelaar, et al. 9, described a pattern of histological features of lung specimens from nine patients in whom no extrathoracic lesions were identified, which they termed “diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis”.

Recognition of the disease requires a high index of suspicion and an extensive workup. Because of its serious morbidity, lymphangiomatosis must always be considered in the differential diagnosis of lytic bone lesions accompanied by chylous effusions, in cases of primary chylopericardium, and as part of the differential diagnosis in pediatric patients presenting with signs of interstitial lung disease 35.

Lymphangiomatosis treatment

There is no standard approach to the treatment of lymphangiomatosis and no cure. Lymphangiomatosis treatment often is aimed at reducing symptoms 32. Surgical intervention may be indicated when complications arise and a number of reports of response to surgical interventions, medications, and dietary approaches can be found in the medical literature 32.

Treatment modalities that have been reported in the medical literature, by system, include:

- Cardiothoracic – Thoracocentesis, pericardiocentesis, pleurodesis, ligation of thoracic duct, pleuroperitoneal shunt, radiation therapy, pleurectomy, pericardial window, pericardiectomy, thalidomide, interferon alpha 2b, Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN), medium chain triglyceride (MCT) and high protein diet, chemotherapy, sclerotherapy, transplant;

- Gastrointestinal/liver/spleen/kidney – interferon alpha 2b, sclerotherapy, resection, percutaneous drainage, Denver shunt, Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN), medium chain triglyceride (MCT) and high protein diet, transplant, splenectomy;

- Skeletal system – interferon alpha 2b, bisphosphonates (i.e. pamidronate), surgical resection, radiation therapy, sclerotherapy, percutaneous bone cement, bone grafts, prosthesis, surgical stabilization.

Lymphangiomatosis life expectancy

Lymphangiomatosis is a multi-system disorder. Lymphangiomatosis life expectancy depends on regions or body systems in which the disease occurs.

The 5-year survival for kaposiform lymphangiomatosis was 51%; overall survival was 34% 19. The cause of death in most instances was cardio-respiratory failure. Mean interval between diagnosis and death was 2.75 years (range, 1.1 to 6.5 years) 19. Outcome for survivors varied; median follow-up was 2.5 years. Three patients continue on pharmacotherapy. Two patients, off treatment for more than 10 years, reported chronic musculoskeletal pain as a prominent, long-term issue. Only one of these patients had major respiratory symptoms; the other had cutaneous staining and functional limitation in the affected extremity prior to therapy. One patient, who presented as an adult, never required intervention and denied any problems 19.

Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis (pulmonary lymphangiomatosis) prognosis is generally poor and treatment is largely supportive, on account of no specific targeting treatments available for this disorder, only with routine symptomatic follow-up 36. Pulmonary lymphangiomatosis can frequently present in childhood, and lead to infiltrative disease, restrictive and/or obstructive ventilation dysfunction, respiratory failure, chylous effusions, lytic bone lesions and mediastinal compression 37, and even death in child and adolescents 38. Children less than 16 years old have a higher mortality rate (∼40%) than adults (0%) 22. Primary causes of death are respiratory failure, infections, and accumulation of chylous fluid. Other manifestations include cervical lymphangioma, pericardial effusions, chyloptysis, hemoptysis, protein-wasting enteropathy, lymphedema, and splenic lesions 39. Lymphangiomas can be associated with the lung parenchyma, pleura, mediastinum, and chest wall. The disease is often misdiagnosed due to nonspecific symptoms (eg, chest pain, chest tightness, shortness of breath, dyspnea, wheezing). Interestingly, patients with lymphangiomatosis with either bone or soft tissue involvement have a better prognosis than those with bone and soft tissue involvement 40. Lymphangiomatosis with bone involvement, can occur without lung involvement 41.

References- Giuliani A, Romano L, Coletti G, et al. Lymphangiomatosis of the ileum with perforation: A case report and review of the literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2019;41:6-10. Published 2019 Mar 29. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2019.03.010 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6449703

- What is lymphangiomatosis? https://www.lgdalliance.org/patient-professional-resources/what-is-lymphangiomatosis

- Watanabe T, Kato K, Sugitani M, Hasunuma O, Sawada T, Hoshino N, Kaneda N, Kawamura F, Arakawa Y, Hirota T. A case of multiple lymphangiomas of the colon suggesting colonic lymphangiomatosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:781–784.

- Faul, J.L., Berry, G.J., Colby, T.V., Ruoss, S.J., Walter, M.B, Rosen, G.D., and Raffin, T.A. Thoracic Lymphangiomas, Lymphangiectasis, Lymphangiomatosis, and Lymphatic Dysplasia Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med., Volume 161, Number 3, March 2000, 1037-1046.

- Agha RA, Borrelli MR, Farwana R, Koshy K, Fowler AJ, Orgill DP; SCARE Group. The SCARE 2018 statement: Updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int J Surg. 2018 Dec;60:132-136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028

- Jung SW, Cha JM, Lee JI, et al. A case report with lymphangiomatosis of the colon. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(1):155-158. doi:10.3346/jkms.2010.25.1.155 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2800000

- Huaringa, A.J., Chittari, L.M., Herzog, C.E., Fanning, C.V., Haro, M. & Eftekhari, F. Pleuro-Pulmonary Lymphangiomatosis: Malignant Behavior Of A Benign Disease . The Internet Journal of Pulmonary Medicine. 2005; 5(2).

- Aviv RI, McHugh K, Hunt J. Angiomatosis of bone and soft tissue: a spectrum of disease from diffuse lymphangiomatosis to vanishing bone disease in young patients. Clin Radiol. 2001 Mar;56(3):184-90.

- Tazelaar HD, Kerr D, Yousem SA, Saldana MJ, Langston C, Colby TV. Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Hum Pathol. 1993 Dec;24(12):1313-22.

- Duffy BM, Manon R, Patel RR, Welsh JS. A case of Gorham’s disease with chylothorax treated curatively with radiation therapy. Clin Med Res. 2005;3(2):83-86. doi:10.3121/cmr.3.2.83 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1183437

- Yeager ND, Hammond S, Mahan J, Davis JT, Adler B. Unique diagnostic features and successful management of a patient with disseminated lymphangiomatosis and chylothorax. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008 Jan;30(1):66-9.

- Croteau SE, Kozakewich HPW, Perez-Atayde AR, & cols. Kaposiform Lymphangiomatosis: A Distinct Aggressive Lymphatic Anomaly. The Journal of pediatrics. 2014; 164(2):383-388. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3946828

- Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/kaposiform-lymphangiomatosis-1?lang=us

- Barclay SF Inman KW, Luks VL, McIntyre JB, Al-Ibraheemi A, Church AJ, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. A somatic activating NRAS variant associated with kaposiform lymphangiomatosis.. Genet Med. Dec 13, 2018; epub:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30542204

- Ozeki M., Fujino A., Matsuoka K., Nosaka S., Kuroda T & Fukao T. Clinical Features and Prognosis of Generalized Lymphatic Anomaly, Kaposiform Lymphangiomatosis, and Gorham–Stout Disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016; 63:832–838. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26806875

- Safi F, Gupta A, Adams D, Anandan V, McCormack FX & Assaly R. Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis, a newly characterized vascular anomaly presenting with hemoptysis in an adult woman. Ann Am Thorac Soc. January, 2014; 11(1):92-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24460439

- Goyal P, Alomari AI & Kozakewich HP. Imaging features of kaposiform lymphangiomatosis. Pediatr Radiol. August, 2016; 46(9):1282-90. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27053281

- Adams DM, Ricci KW. Vascular Anomalies: Diagnosis of Complicated Anomalies and New Medical Treatment Options. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. Jun 2019; 33(3):455-470. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31030813

- Croteau SE, Kozakewich HP, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis: a distinct aggressive lymphatic anomaly. J Pediatr. 2014;164(2):383-388. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.013 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3946828

- Diffuse Pulmonary Lymphangiomatosis. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/diffuse-pulmonary-lymphangiomatosis

- Biscotto, Igor, Rodrigues, Rosana Souza, Forny, Danielle Nunes, Barreto, Miriam Menna, & Marchiori, Edson. (2019). Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia, 45(5), e20180412. Epub September 16, 2019.https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-3713/e20180412

- Fukahori S, Tsuru T, Asagiri K, Nakamizo H, Asakawa T, Tanaka H, Tanaka Y, Akiba J, Yano H, Yagi M. Thoracic lymphangiomatosis with massive chylothorax after a tumor biopsy and with disseminated intravenous coagulation–lymphoscintigraphy, an alternative minimally invasive imaging technique: report of a case. Surg Today. 2011 Jul;41(7):978-82. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4383-0

- Dupond, J.L., Bermont, L., Runge, M., de Billy, M. Plasma VEGF determination in disseminated lymphangiomatosis-Gorham-Stout syndrome: a marker of activity? A case report with a 5-year follow-up. Bone.2010 Mar;46(3):873-6.

- Venkatramani R, Ma NS, Pitukcheewanont P, Malogolowkin MH, Mascarenhas L. Gorham’s disease and diffuse lymphangiomatosis in children and adolescents. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011 Apr;56(4):667-70

- Zisis C, Spiliotopoulos K, Patronis M, Filippakis G, Stratakos G, Tzelepis G, Bellenis I. Diffuse lymphangiomatosis: are there any clinical or therapeutic standards? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007 Jun;133(6):1664-5.

- O’Sullivan DA, Torres VE, de Groen PC, Batts KP, King BF, Vockley J. Hepatic lymphangiomatosis mimicking polycystic liver disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998 Dec;73(12):1188-92.

- Miller C, Mazzaferro V, Makowka L, ChapChap P, Demetris J, Tzakis A, Esquivel CO, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Orthotopic liver transplantation for massive hepatic lymphangiomatosis. Surgery. 1988 Apr;103(4):490-5.

- Watkins RG 4th, Reynolds RA, McComb JG, Tolo VT. Lymphangiomatosis of the spine: two cases requiring surgical intervention. Spine. 2003 Feb 1;28(3):E45-50.

- Jea A, McNeil A, Bhatia S, Birchansky S, Sotrel A, Ragheb J, Morrison G. A rare case of lymphangiomatosis of the craniocervical spine in conjunction with a Chiari I malformation. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2003 Oct;39(4):212-5.

- Shah V, Shah S, Barnacle A, Sebire NJ, Brock P, Harper JI, McHugh K. Mediastinal involvement in lymphangiomatosis: a previously unreported MRI sign. Pediatr Radiol. 2011 Aug;41(8):985-92.

- CS Wong, TYC Chu. Clinical and radiological features of generalised lymphangiomatosis. Hong Kong Med J 2008;14:402-4.

- DU Ming-hua, YE Ruan-jian, SUN Kun-kun, LI Jian-feng, SHEN Dan-hua, WANG Jun and GAO Zhan-cheng. Diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis: a case report with literature review. Chinese Medical Journal. 2011;124(5):797-800

- Harnisch, E., Sukhai, R., Oudesluys-Murphy, AM., Serious complications of pulmonary biopsy in a boy with chylopericardium and suspected pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. BMJ Case Reports 2010; Published 1 January 2010;published online 6 May 2010, doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2009.2206

- Lymphangiomatosis. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/softtissuelymphangiomatosis.html

- Martinez-Pajares JD, Rosa-Camacho V, Camacho-Alonso JM, Zabala-Arguelles I, Gil-Jaurena JM, Milano-Manso G. Spontaneous chylous pericardial effusion: report of two cases. An Pediatr (Barc). 2010 Jul;73(1):42-6.

- Ozeki M, Fukao T, Kondo N. Propranolol for intractable diffuse lymphangiomatosis. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1380-2. 10.1056/NEJMc1013217

- Satria MN, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Moss J. Pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Lymphat Res Biol. 2011;9(4):191-193. doi:10.1089/lrb.2011.0023 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3246407

- Zhao J, Wu R, Gu Y. Pathology analysis of a rare case of diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(6):114. doi:10.21037/atm.2016.03.30 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4828737

- Radhakrishnan K. Rockson SG. The clinical spectrum of lymphatic disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1131:155–184.

- Faul JL, et al. Thoracic lymphangiomas, lymphangiectasis, lymphangiomatosis, and lymphatic dysplasia syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1037–1046.

- Aviv RI. McHugh K. Hunt J. Angiomatosis of bone and soft tissue: A spectrum of disease from diffuse lymphangiomatosis to vanishing bone disease in young patients. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:184–190.