Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) is now called undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) or malignant fibrous cytoma, is a cancer believed to originate from primitive mesenchymal cells; arising from soft tissue or bone, usually in the extremities or retroperitoneum 1. The term malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) was removed from the 2013 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone 2. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma is now classified under the undifferentiated or unclassified sarcomas group 3. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma or MFH cancer can occur anywhere in the body, but it usually occurs in the legs (especially the thighs ~50% of the cases), arms (~20% of the cases) or back of the abdomen 4. Retroperitoneal malignant fibrous histiocytoma represent about 16% of the cases and, those involving the peritoneal cavity, about 5-10% 4. Involvement of the abdominal viscera is described as extremely rare. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma may also occur in a part of the body where a patient received radiation therapy in the past. Malignant fibrous histiocytomas are aggressive tumors, often grow quickly and spread to other parts of the body, including the lungs. They usually occur in older adults, and they may sometimes occur as a second cancer in patients who had retinoblastoma. Typically, malignant fibrous histiocytoma occurs in adults (range 32-80; mean 59 years) with a slight male predilection with an Male: Female ratio of 1.2:1 5.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of late adult life, currently it accounts for ~5% of adult sarcomas 6 and has a slight male predominance 7. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma has been categorized into five subtypes: (a) storiform or pleomorphic, (b) myxoid, (c) giant cell, (d) inflammatory and (e) angiomatoid 8. The most common is storiform or pleomorphic that forms 50–60% of all such tumors while myxoid type is the second most common at 25% 5. One risk factor is radiotherapy 9; about 20% of all sarcomas are the undifferentiated or unclassified type and about a quarter of those are radiation related 10. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma has an aggressive biological behavior and a poor prognosis. Patients usually present late with metastasis, most frequently to lungs or lymph nodes 11. Imaging like computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans play a role in defining the extent of the disease and the treatment is mainly surgical. There may be a role for neoadjuvant or adjuvant radiotherapy 12. This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria 13.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma treatment usually consists of aggressive en bloc resection with a wide margin. En bloc resection involves the surgical removal of the entirety of a tumor without violating its capsule, and requires resection of the lesion encased by a continuous margin of healthy tissue 14. Supplementary neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy 15 is especially useful in reducing the local recurrence rate 16. Limb-sparing surgery is usually possible 16.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma key points

- Malignant fibrous histiocytoma is a curable disease.

- The term “Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma” has been changed by the WHO to Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma Not Otherwise Specified.

- The mainstays of treatment for malignant fibrous histiocytoma are complete surgical excision most often supplemented with adjuvant radiation therapy.

- Chemotherapy is reserved for patients at the highest risk of disease recurrence or patients that already have recurrence.

- Patients with recurrent malignant fibrous histiocytoma can still be cured.

- Favorable prognostic factors that correspond to superior survival include small tumor size, low grade, extremity location, superficial location, and localized disease.

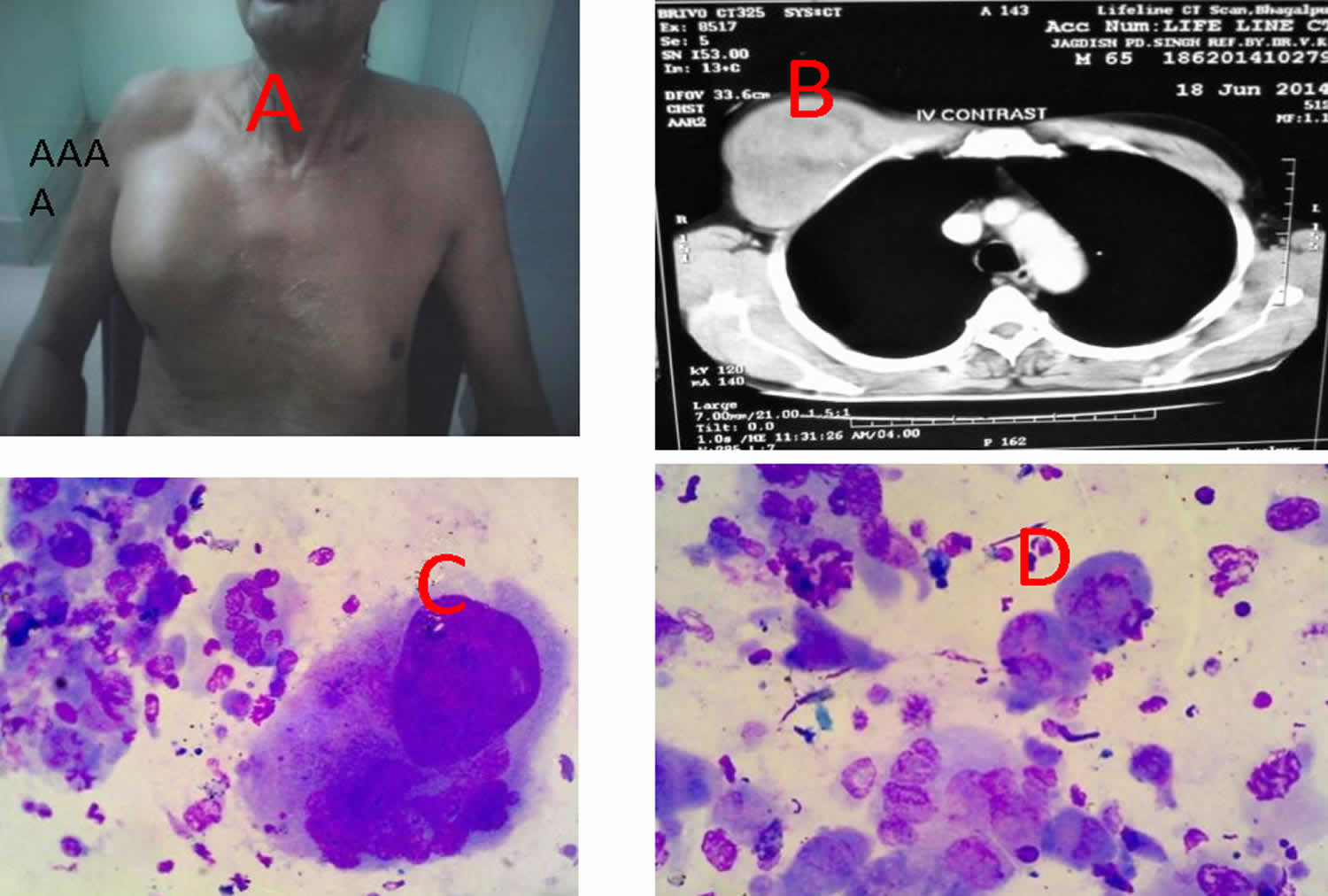

Figure 1. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

Footnote: (A) Photograph showing large soft mass in right upper chest wall (B) CT scan revealing destructive lesion involving pectoralis muscle & pushing the pleura (C,D) microphotograph showing pleomorphic tumour cells with bizarre nuclei & osteoclastlike giant cells

[Source 8 ]What is a soft tissue sarcoma?

A sarcoma is a type of cancer that starts in tissues like bone or muscle. Bone and soft tissue sarcomas are the main types of sarcoma. Soft tissue sarcomas can develop in soft tissues like fat, muscle, nerves, fibrous tissues, blood vessels, or deep skin tissues. They can be found in any part of the body. Most of them start in the arms or legs. They can also be found in the trunk, head and neck area, internal organs, and the area in back of the abdominal (belly) cavity (known as the retroperitoneum). Sarcomas are not common tumors.

The most common types of sarcoma in adults are:

- Malignant fibrous histiocytoma or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma

- Liposarcoma

- Leiomyosarcoma

Certain types occur more often in certain parts of the body more often than others. For example, leiomyosarcomas are the most common type of sarcoma found in the abdomen (belly), while liposarcomas and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas are most common in legs. But pathologists (doctors who specialize in diagnosing cancers by how they look under the microscope), may not always agree on the exact type of sarcoma. Sarcomas of uncertain type are very common.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma causes

Scientists don’t know exactly what causes most soft tissue sarcomas, but they have found some risk factors that can make a person more likely to develop these cancers. And research has shown that some of these risk factors affect the genes in cells in the soft tissues.

Risk factors can include radiation treatment for another malignancy like Hodgkin’s lymphoma 17, post breast cancer resection radiotherapy 9, background history of Paget’s disease, non ossifying fibroma and fibrous dysplasia. Soft tissue sarcoma has been linked to certain syndromes such as Werner, Gardner, Li Fraumeni and Von Recklinghausen 8.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma symptoms

As with all sarcomas of soft tissue and bone, malignant fibrous histiocytoma is rare, with just a few thousand cases diagnosed each year. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of soft tissue typically presents in a patient that is approximately 50 to 70 years of age though it can appear at any age. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma is very rare in persons less than 20 years old.

There is a slight male predominance. Soft tissue malignant fibrous histiocytoma can arise in any part of the body but most commonly in the lower extremity, especially the thigh. Other common locations include the upper extremity and retroperitoneum. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma has been reported to occur in the lungs, liver, kidneys, bladder, scrotum, vas deferens, heart, aorta, stomach, small intestine, orbit, central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), paraspinal area, dura mater, facial sinuses, nasal cavity, oral cavity, nasopharynx, and soft tissues of the neck 18.

Symptoms are usually a painless, enlarging palpable mass. Local mass effect symptoms may be caused depending on location. Patients often complain of an enlarging painless soft-tissue mass or lump (typically 5-10 cm in diameter) that has arisen over a short period of time ranging from weeks to months 19. The majority of malignant fibrous histiocytoma tumors are intramuscular. It is not uncommon for patients to report trauma to the affected area. For example, patients will state that they “ran into the corner of a table” and have had a thigh lump since. Trauma as far as what experts know does not cause malignant fibrous histiocytoma but rather the incident draws attention to the site. The mass does not usually cause any pain unless it is compressing a nearby nerve. Symptoms such as weight loss and fatigue are not typical but can present in patients with advanced disease. Retroperitoneal tumors can become quite large before they are detected as patients do not feel a mass per se, but rather associated constitutional symptoms such as anorexia, increased abdominal pressure, fever, malaise, and weight loss 10. The tumor is often large at presentation and may cause displacement of the bowel, kidney, ureter, and/or bladder.

Rare signs and symptoms of malignant fibrous histiocytoma include episodic hypoglycemia and rapid tumor enlargement during pregnancy 19. Additionally, malignant fibrous histiocytoma has been associated with hematopoietic diseases such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and malignant histiocytosis.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma may also occur secondary to radiation exposure and shrapnel injury and may be seen adjacent to metallic fixation devices, including total joint prostheses 19. Early and complete surgical removal using wide or radical resection is indicated because of the aggressive nature of the tumor.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma diagnosis

Often an x-ray is obtained as the first imaging test. Usually this is followed with an MRI. MRI is the most useful test to image soft tissue tumors as it provides very valuable information about the mass such as the size, location, and proximity to neurovascular structures. It is important to note that the diagnosis of a cancerous tumor cannot be made by MRI alone. For patients that are unable to undergo MRI because of metallic implants such as pacemakers, a CT scan may be obtained.

As with other soft-tissue tumors, MRI is the imaging method of choice because of its ability to provide superior contrast between tumor and muscle, excellent definition of surrounding anatomy, and ease of imaging in multiple planes 20. However, no single imaging technique can provide a specific histologic diagnosis of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, and biopsy is usually necessary. After analyzing all of the information that has been gathered, if the mass remains suspicious for sarcoma the patient will likely be referred to a physician who specializes in sarcoma. The specialist, usually an orthopaedic oncologist or general surgical oncologist, will then likely perform additional tests and arrange for a biopsy.

If the radiologist is asked to perform a biopsy on a potentially malignant soft-tissue mass, the orthopedic surgeon resecting the mass must be consulted first. With certain tumors, the biopsy tract must be removed with the mass; a presurgical image-guided biopsy performed without appropriate orthopedic consultation may result in more extensive surgery (including amputation) than would have been necessary otherwise.

When the diagnosis of malignant fibrous histiocytoma is suspected, it is important to determine if a tumor is isolated (localized) or has spread (metastatic). When soft tissue sarcomas spread, they most commonly metastasize to the lungs. As such, a CT scan of the chest is routinely obtained to determine the presence or absence of metastatic disease. While sarcomas including malignant fibrous histiocytoma can spread to other sites such as lymph nodes and bones, it is fairly uncommon. The role of tests such as bone scan and PET scan is not totally clear 21. There is considerable variability among physicians as to whether these additional studies are useful.

Macroscopic appearance

Macroscopically, these tumors are typically large (5-20 cm) well circumscribed but unencapsulated with a grey firm heterogeneous cut surface sometimes with areas of necrosis 5.

Biopsy

A biopsy is a procedure in which diagnostic tissue is obtained. Biopsies can be performed by different methods. A needle biopsy involves inserting a small needle into the tumor to obtain a specimen 22. Needle biopsies, can often be performed in the physician’s office. If the tumor is in a location that is difficult to feel or there are structures near the tumor that could be damaged, then a CT-guided needle biopsy might be arranged.

An open biopsy is a surgical procedure that is usually performed in the operating room under sedation or anesthesia. With incisional biopsies, just a small part of the tumor is removed for analysis. With excisional biopsies, the entire mass is removed. Excisional biopsies are usually reserved for small tumors (less than 3 cm).

The decision to remove part of the mass or the entire mass at the time of biopsy is extremely critical. The importance of having a sarcoma specialist either perform the actual biopsy or guide the treating surgeon in planning a biopsy cannot be overstated.

The biopsy is often the first step to a successful limb-sparing procedure. The location of the biopsy incision and technical aspects of obtaining tissue can have a major impact on subsequent operations 23.

The tissue obtained from the biopsy is evaluated by a pathologist. The pathologist uses a number of diagnostic tools including light microscopy, immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and molecular studies to make the diagnosis. In addition to making a diagnosis, the pathologist also provides an important piece of information called the grade. The grade refers to a tumor’s appearance under the microscope and is a reflection of a tumor’s aggressiveness. High grade tumors behave more aggressively meaning they have a higher tendency to recur and spread. Low grade tumors are less aggressive and have a lower tendency to recur and spread. The grade is not a guarantee of a tumor’s behavior but rather is one of the factors that helps the treatment team make recommendations.

Histology

Microscopically malignant fibrous histiocytoma are heterogeneous fibroblastic tumors made up of poorly differentiated fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, histiocyte-like cells with significant cellular pleomorphism, storiform architecture and also demonstrate bizarre multi-nucleated giant cells 5. They are sometimes difficult to distinguish from other high-grade sarcomas. A number of histological subtypes have been described including 24:

- Storiform-pleomorphic: most common 50-70% of cases

- Myxoid: 25% of cases, myxofibrosarcoma. The myxoid subtype must contain at least 50% myxoid areas by definition. Occasionally an entire nodule of tumor can have a myxoid appearance causing diagnostic confusion including less aggressive entities such as myxoma or nodular fasciitis. Unlike the other sub-types of malignant fibrous histiocytoma, the myxoid form tends to be less aggressive and as a result is associated with a better prognosis.

- Inflammatory: 5-10% of cases (tends to occur in the retroperitoneum)

- Giant cell: 5-10% of cases

- Angiomatoid

- relatively non-aggressive

- metastases uncommon

- usually occurs in young adults/adolescents

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma staging

Once all of the imaging studies and biopsy have been performed, the stage of disease can be assigned. The most commonly used staging system is the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system for soft tissue sarcoma, which is based on 4 key pieces of information (see Tables 1 and 2). Patients often inquire about the stage of their disease. It must be kept in mind that stage is not a guarantee of a tumor’s behavior. Staging merely provides guidelines for the treatment team on how best to manage a given tumor to optimize clinical outcome.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system 25:

- The extent of the tumor (T): How large is the cancer?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant organs such as the lungs?

- The grade (G) of the cancer: How much do the sarcoma cells look like normal cells?

Grade

The grade is partly used to determine the stage of a sarcoma. The staging system divides sarcomas into 3 grades (1 to 3). The grade of a sarcoma helps predict how rapidly it will grow and spread. It’s useful in predicting a patient’s outlook and helps determine treatment options.

The grade of a sarcoma is determined using a system known as the French or FNCLCC system, and is based on 3 factors:

- Differentiation: Cancer cells are given a score of 1 to 3, with 1 being assigned when they look a lot like normal cells and 3 being used when the cancer cells look very abnormal. Certain types of sarcoma are given a higher score automatically.

- Mitotic count: How many cancer cells are seen dividing under the microscope; given a score from 1 to 3 (a lower score means fewer cells were seen dividing)

- Tumor necrosis: How much of the tumor is made up of dying tissue; given a score from 0 to 2 (a lower score means there was less dying tissue present).

Each factor is given a score, and the scores are added to determine the grade of the tumor. Sarcomas that have cells that look more normal and have fewer cells dividing are generally placed in a low-grade category. Low-grade tumors tend to be slow growing, slower to spread, and often have a better outlook (prognosis) than higher-grade tumors. Certain types of sarcoma are automatically given higher differentiation scores. This affects the overall score so much that they are never considered low grade. Examples of these include synovial sarcomas and embryonal sarcomas. Here’s what the grade numbers mean:

- GX: The grade cannot be assessed (because of incomplete information).

- Grade 1 (G1): Total score of 2 or 3

- Grade 2 (G2): Total score of 4 or 5

- Grade 3 (G3): Total score of 6, 7 or 8

Defining TNM

There are different staging systems for soft tissue sarcomas depending on where the cancer is in the body.

- Head and neck

- Trunk and extremities (arms and legs)

- Abdomen and thoracic (chest) visceral organs

- Retroperitoneum

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage. Of the 4 main locations, only 2 (Trunk and Extremities and Retroperitoneum) have stage groupings.

The staging system in Tables 1 and 2 below uses the pathologic stage also called the surgical stage. It is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. Sometimes, if surgery is not possible right away or at all, the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests. The clinical stage will be used to help plan treatment. Sometimes, though, the cancer has spread further than the clinical stage estimates, and may not predict the patient’s outlook as accurately as a pathologic stage.

The system described below is the most recent AJCC system, effective January 2018. Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 1. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Trunk and Extremities Sarcoma Stages

Stage groupingTrunk and Extremities Sarcoma Stage description*

| AJCC stage | Stage grouping | Trunk and Extremities Sarcoma Stage description* |

|---|---|---|

| IA | T1 N0 M0 G1 or GX | The cancer is 5 cm (2 inches) or smaller (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The cancer is grade 1 (G1) or the grade cannot be assessed (GX). |

| IB | T2, T3, T4 N0 M0 G1 or GX | The cancer is:

It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The cancer is grade 1 (G1) or the grade cannot be assessed (GX). |

| II | T1 N0 M0 G2 or G3 | The cancer is 5 cm (2 inches) or smaller (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The cancer is grade 2 (G2) or grade 3 (G3). |

| IIIA | T2 N0 M0 G2 or G3 | The cancer is larger than 5 cm (2 inches) but not more than 10 cm (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The cancer is grade 2 (G2) or grade 3 (G3). |

| IIIB | T3 or T4 N0 M0 G2 or G3 | The cancer is:

It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The cancer is grade 2 (G2) or grade 3 (G3). |

| IV | Any T N1 M0 Any G | The cancer is any size (Any T) AND it has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). It can be any grade. |

| OR | ||

| Any T Any N M1 Any G | The cancer is any size (Any T) AND it has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has spread to distant sites such as the lungs (M1). It can be any grade. | |

Footnote: *The following categories are not listed in the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Table 2. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Retroperitoneum Sarcoma Stages

| AJCC stage | Stage grouping | Retroperitoneum Sarcoma Stage description* |

|---|---|---|

| IA | T1 N0 M0 G1 or GX | The cancer is 5 cm (2 inches) or smaller (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The cancer is grade 1 (G1) or the grade cannot be assessed (GX). |

| IB | T2, T3, T4 N0 M0 G1 or GX | The cancer is:

It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The cancer is grade 1 (G1) or the grade cannot be assessed (GX). |

| II | T1 N0 M0 G2 or G3 | The cancer is 5 cm (2 inches) or smaller (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The cancer is grade 2 (G2) or grade 3 (G3). |

| IIIA | T2 N0 M0 G2 or G3 | The cancer is larger than 5 cm (2 inches) but not more than 10 cm (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The cancer is grade 2 (G2) or grade 3 (G3). |

| IIIB | T3 or T4 N0 M0 G2 or G3 | The cancer is:

It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). The cancer is grade 2 (G2) or grade 3 (G3). |

| OR | ||

| Any T N1 M0 Any G | The cancer is any size (Any T) AND it has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). It can be any grade. | |

| IV | Any T Any N M1 Any G | The cancer is any size (Any T) AND it has spread to nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has spread to distant sites such as the lungs (M1). It can be any grade. |

Footnote: *The following categories are not listed in the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma treatment

If you’ve been diagnosed with a soft tissue sarcoma, your treatment team will discuss your options with you. It’s important to weigh the benefits of each treatment option against the possible risks and side effects.

There are essentially three main types of treatment that will need to be coordinated to treat the malignant fibrous histiocytoma:

- Surgery

- Radiation

- Chemotherapy

The main treatment of malignant fibrous histiocytoma remains complete surgical excision, with margins of at least 2 cm with a role for neoadjuvant/adjuvant radiotherapy and doxorubicin based chemotherapy 12.

Sarcoma treatment requires a multimodality approach and hence a team of physicians will participate in a patient’s care. Based on your treatment options, you might have different types of doctors on your treatment team. These doctors could include:

- An orthopedic surgeon: specializes in diseases of the bones, muscles, and joints (for sarcomas in the arms and legs)

- A surgical oncologist: treats cancer with surgery (for sarcomas in the abdomen [belly] and retroperitoneum [the back of the abdomen])

- A thoracic surgeon: treats diseases of the lungs and chest with surgery (for sarcomas in the chest)

- A medical oncologist: treats cancer with medicines like chemotherapy

- A radiation oncologist: treats cancer with radiation therapy

- A physiatrist (or rehabilitation doctor): treats injuries or illnesses that affect how you move

Surgery

Surgery is commonly used to treat soft tissue sarcomas. Depending on the site and size of a sarcoma, surgery might be able to remove the cancer. The goal of surgery is to remove the entire tumor along with at least 1 to 2 cm (less than an inch) of the normal tissue around it. This is to make sure that no cancer cells are left behind. When the removed tissue is looked at under a microscope, the doctor will check to see if cancer is growing in the edges (margins) of the specimen.

- If cancer cells are found at the edges of the removed tissue, it is said to have positive margins. This means that cancer cells may have been left behind. When cancer cells are left after surgery, more treatment − such as radiation or another surgery — might be needed.

- If cancer isn’t growing into the edges of the tissue removed, it’s said to have negative or clear margins. The sarcoma has much less chance of coming back after surgery if it’s removed with clear margins. In this case, surgery may be the only treatment needed.

When the tumor is in the abdomen, it can be hard to remove it and enough normal tissue to get clear margins because the tumor could be next to vital organs that can’t be taken out.

Amputation and limb-sparing surgery

In the past, many sarcomas in the arms and legs were treated by removing the limb (amputation). Today, this is rarely needed. Instead, the standard is surgery to remove the tumor without amputation. This is called limb-sparing surgery. A tissue graft or an implant may be used to replace the removed tissue. This might be followed by radiation therapy.

Sometimes, an amputation can’t be avoided. It might be the only way to remove all of the cancer. Other times, key nerves, muscles, bone, and blood vessels would have to be removed along with the cancer. If removing this tissue would mean leaving a limb that doesn’t work well or would result in chronic pain, amputation may be the best option.

Surgery if sarcoma has spread

If the sarcoma has spread to distant sites (like the lungs or other organs), all of the cancer will be removed if possible. That includes the original tumor plus the areas of spread. If it isn’t possible to remove all of the sarcoma, then surgery may not be done at all.

Most of the time, surgery alone cannot cure a sarcoma once it has spread. But if it has only spread to a few spots in the lung, the metastatic tumors can sometimes be removed. This can cure patients, or at least lead to long-term survival.

Lymph node dissection

If lymph nodes near the tumor are enlarged, cancer may be in them. During surgery, some of the swollen nodes may be sent to the lab and checked for cancer. If cancer is found, the lymph nodes in the area will be removed. Radiation might be used in that area after surgery.

Treatments used with surgery

Sometimes chemotherapy (chemo), radiation, or both may be given before surgery. This is called neoadjuvant treatment. It can be used to shrink the tumor so that it can be removed completely. Chemotherapy or radiation can also be given before surgery to treat high-grade sarcomas when there’s a high risk of the cancer spreading.

Chemo and/or radiation may also be used after surgery. This is called adjuvant treatment. The goal is to kill any cancer cells that may be left in the body to lower the risk of the cancer coming back.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy rays (such as x-rays) or particles to kill cancer cells. It’s a key part of soft tissue sarcoma treatment.

- Most of the time radiation is given after surgery. This is called adjuvant treatment. It’s done to kill any cancer cells that may be left behind after surgery. Radiation can affect wound healing, so it may not be started until a month or so after surgery.

- Radiation may also be used before surgery to shrink the tumor and make it easier to remove. This is called neoadjuvant treatment.

Radiation can be the main treatment for sarcoma in someone who isn’t healthy enough to have surgery. Radiation therapy can also be used to help ease symptoms of sarcoma when it has spread. This is called palliative treatment.

Types of radiation therapy

- External beam radiation: This is the type of radiation therapy most often used to treat sarcomas. Treatments are often given daily, 5 days a week, usually for several weeks. In most cases, a technique called intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is used. This better focuses the radiation on the cancer and lessens the damage to healthy tissue.

- Proton beam radiation: This uses streams of protons instead of x-ray beams to treat the cancer. Although this has some advantages over intensity modulated radiation therapy in theory, it hasn’t been proven to be a better treatment for soft tissue sarcoma. Proton beam therapy is not widely available.

- Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT): For this treatment, one large dose of radiation is given in the operating room after the tumor is removed but before the wound is closed. Giving radiation this way means that it doesn’t have to travel through healthy tissue to get to the area that needs to be treated. It also allows nearby healthy areas to be shielded more easily from the radiation. Often, intraoperative radiation therapy is only one part of radiation therapy, and the patient gets some other type of radiation after surgery.

- Brachytherapy: Sometimes called internal radiation therapy, is a treatment that places small pellets (or seeds) of radioactive material in or near the cancer. For soft tissue sarcoma, these pellets are put into catheters (very thin, soft tubes) that have been placed during surgery. Brachytherapy may be the only form of radiation therapy used or it can be combined with external beam radiation.

Chemoradiation

After surgery, some high-grade sarcomas may be treated with radiation and chemotherapy at the same time. This is called chemoradiation.

This may also be done before surgery in cases where the sarcoma cannot be removed or removing it would cause major damage. Sometimes, chemoradiation can shrink the tumor enough to take care of these issues so it can be removed.

Chemoradiation can cause major side effects. And not all experts agree on its value in treating sarcoma. Radiation alone after surgery seems to works as well as chemoradiation. Still for some cases, this may be a treatment option to consider.

Side effects of radiation treatment

Side effects of radiation therapy depend on the part of the body treated and the dose given. Common side effects include:

- Skin changes where the radiation went through the skin, which can range from redness to blistering and peeling

- Fatigue

- Nausea and vomiting (more common with radiation to the belly)

- Diarrhea (most common with radiation to the pelvis and belly)

- Pain with swallowing (from radiation to the head, neck, or chest)

- Lung damage leading to problems breathing (from radiation to the chest)

- Bone weakness, which can lead to fractures or breaks years later

Radiation of large areas of an arm or leg can cause swelling, pain, and weakness in that limb.

Side effects of radiation therapy to the brain for metastatic sarcoma include hair loss (in this case, it can be permanent), headaches, and problems thinking.

If given before surgery, radiation may cause problems with wound healing. If given after surgery, it can cause long-term stiffness and swelling that can affect how well the limb works.

Many side effects improve or even go away after radiation is finished. Some though, like bone weakness and lung damage, can be permanent.

Chemotherapy

The role of chemotherapy in the treatment of malignant fibrous histiocytoma is not entirely clear. Chemotherapy (chemo) is the use of drugs given into a vein or taken by mouth to treat cancer. These drugs enter the bloodstream and reach all areas of the body, making this treatment useful for cancer that has spread (metastasized) to other organs.

Several clinical trials incorporating the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin have shown trends in improved event-free survival without a major impact on overall survival. The results of a large meta-analysis which included almost 1,600 soft tissue sarcoma patients concluded that the addition of chemotherapy improved overall survival by less than 10% 26. Results were better in patients with extremity tumors than in patients with axial or retroperitoneal tumors. More recently, clinical trials incorporating ifosfamide and doxorubicin have demonstrated an improvement in disease-free survival 27. One of the major limitations of chemotherapy is the associated toxicities with the doses necessary to have a significant impact on disease-specific survival. The addition of supportive drugs such as hematopoietic growth factors has allowed for higher doses and trends in improved survival are being observed.

Unfortunately, the interpretation of these and other chemotherapy trials results has varied so much that it has become difficult for patients to decipher the information in order to make decisions regarding chemotherapy as part of their treatment. The decision to incorporate chemotherapy in the treatment of malignant fibrous histiocytoma must be made with the guidance of a medical oncologist. Chemotherapy probably should be given to patients who already have metastatic disease or who are at the highest risk for developing metastatic disease. Most often, chemotherapy will likely be administered in the setting of a clinical trial.

Follow-up care and surveillance

Probably about 1/3 of patients with extremity malignant fibrous histiocytoma and closer to 1/2 of patients with retroperitoneal malignant fibrous histiocytoma will experience recurrence either in the primary site (local recurrence) or at a distant site (distant recurrence or metastasis). Most recurrences usually develop in the first 2 years following treatment but may occur at any time during a patient’s lifetime. The frequency and length of follow-up vary according to the number of risk factors an individual has for developing a recurrence. On average patients are followed for approximately 10 years. Patients with large or high grade tumors will likely be evaluated every few months initially where as patients with low grade or small tumors will probably be seen annually. A follow-up exam consists of a physical examination and a chest evaluation in the form of an x-ray or CT-scan. Depending on the circumstances, an MRI of the primary site may be obtained.

If a recurrence is detected, the treatment team collaborates again to determine the roles of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Most local recurrences can be effectively treated with additional surgery. For recurrent local disease that is resectable, approximately 2/3 of patients experience long term survival 28. If no prior radiation was administered, the affected area should receive radiation for the recurrence. Metastatic disease represents the most serious type of recurrence and most commonly occurs in the lungs. Individual treatment plans vary significantly depending on a host of patient and disease factors as well as the limitations imposed by previous treatments. For patients that have isolated resectable pulmonary metastases, it is possible to achieve extended survival in approximately 20% to 50% of patients 29. Chemotherapy is often incorporated into the treatment of patients with distant recurrence. Unfortunately, patients with unresectable recurrent disease have a uniformly poor prognosis.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma prognosis

Most malignant fibrous histiocytoma are of high grade (3 and 4) and are aggressive in their biological behavior. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma frequently metastasize (30-50% at diagnosis) and locally recur despite aggressive treatment 24. In a study done by Kearney et al. 30, a local recurrence rate of 51% was seen in patients with a ‘complete excision’.

Prognostic factors include 31, 32, 33:

- Tumor size: smaller being better

- Location

- superficial is better

- distal is better

- Histological grade

- Histological subtype: the myxoid subtype has a better prognosis as compared to the storiform-pleomorphic subtype 6.

Favorable prognostic factors include age less than 60 years old, tumor size less than 5 cm, superficial location, low grade, the absence of metastatic disease, and a myxoid subtype. Older patients with large (> 5cm), deeply seated, high grade tumors do not have as favorable an outcome. For example, patients with a small low grade tumor are likely to achieve complete cure. For patients with large, deep, high grade tumors (Stage 3), the 5 year survival estimates range from 34 to 70% 34. A tumor located superficially in the subcutaneous tissues of the distal extremity and measuring less than 5 cm, has a 5-year survival of 80%, whereas a proximal large (>5 cm) and deep tumor has a 5-year survival of 55% 16.

The overall 5-year survival is between 25-70% 35. Pezzi et al. 11 found that the primary tumor size indicated the 5-year survival rate: tumors <5 cm had a survival rate of 82%; 5–10 cm, 68%; and >10 cm, 51%. The intermediate grade tumors showed a 5-year survival rate of 80%, and the 5-year survival rate for high-grade tumors was 60%. Survival rates for both grades were affected by size: tumors of high grade and smaller than 5 cm in diameter had a survival rate of 79%; 5–10 cm, 63%; and more than 10 cm, 41%.

References- Kumar V., Abbas A.K., Aster J.C. 9th ed. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2013. Robbins Basic Pathology.

- Doyle, L.A. (2014), Sarcoma classification: An update based on the 2013 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. Cancer, 120: 1763-1774. doi:10.1002/cncr.28657 https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28657

- Edge S.B., Greene F.L., Page D.L., Fleming I.D., Fritz A.G., Balch C.M. 8th ed. Springer – Verlag New York, Inc.; USA: 2017. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System for Soft Tissue Sarcoma.

- Karki B, Xu YK, Wu YK, Zhang WW. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the abdominal cavity: CT findings and pathological correlation. (2012) World journal of radiology. 4 (4): 151-8. doi:10.4329/wjr.v4.i4.151

- Meyers SP. MRI of bone and soft tissue tumors and tumorlike lesions, differential diagnosis and atlas. Thieme Publishing Group. (2008) ISBN:3131354216

- Razek AA, Huang BY. Soft tissue tumors of the head and neck: imaging-based review of the WHO classification. Radiographics. 2011 Nov-Dec;31(7):1923-54. doi: 10.1148/rg.317115095

- Weiss S.W., Enzinger F.M. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: an analysis of 200 cases. Cancer. 1978;41(June (6):2250–2266.

- Seomangal K, Mahmoud N, McGrath JP. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma, now referred to as Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma: A Case Report of an unexpected histology of a subcutaneous lesion. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;60:299-302. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.06.035 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6611999

- Kocer B., Gulbahar G., Erdogan B., Budakoglu B., Erekul S., Dural K. A case of radiation-induced sternal malignant fibrous histiocytoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgical resection. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2008;(December 6):138.

- Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma. http://sarcomahelp.org/mfh.html

- Pezzi C.M., Rawlings M.S., Esgro J.J., Pollock R.E., Romsdahl M.M. Prognostic factors in 227 patients with Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma. Cancer. 1992;69(8):2098–2103.

- Chen K.-H., Chou T.-M., Shieh S.-J. Management of extremity malignant fibrous histiocytoma: a 10-year experience. Formos. J. Surg. 2015;48:1–9.

- Agha RA, Borrelli MR, Farwana R, Koshy K, Fowler AJ, Orgill DP; SCARE Group. The SCARE 2018 statement: Updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int J Surg. 2018 Dec;60:132-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028

- Howell EP, Williamson T, Karikari I, et al. Total en bloc resection of primary and metastatic spine tumors. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(10):226. doi:10.21037/atm.2019.01.25 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6595209

- Manaster BJ, Disler DG, May DA et-al. Musculoskeletal imaging, the requisites. Mosby Inc. (2002) ISBN:0323011896

- Skinner HB. Current diagnosis & treatment in orthopedics. McGraw-Hill Medical. (2003) ISBN:0071387587

- Mandal S., Mandal A.K. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma following radiation therapy and chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;12(February (1):52–55.

- Cong Z, Gong J. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the liver: CT findings in five histopathological proven patients. Abdom Imaging. 2011 Oct. 36(5):552-6.

- Pleomorphic Sarcoma (Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma) of Soft Tissue Imaging. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/391453-overview

- Amit P, Patro DK, Basu D, Elangovan S, Parathasarathy V. Role of Dynamic MRI and Clinical Assessment in Predicting Histologic Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Bone Sarcomas. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013 Feb 5.

- Jager, P. L.; Hoekstra, H. J.; Leeuw, J.; van Der Graaf, W. T.; de Vries, E. G.; and Piers, D.: Routine bone scintigraphy in primary staging of soft tissue sarcoma; Is it worthwhile? Cancer, 89(8): 1726-31, 2000.

- Heslin, M. J.; Lewis, J. J.; Woodruff, J. M.; and Brennan, M. F.: Core needle biopsy for diagnosis of extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol, 4(5): 425-31, 1997.

- Mankin, H. J.; Mankin, C. J.; and Simon, M. A.: The hazards of the biopsy, revisited. Members of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 78(5): 656-63, 1996.

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N et-al. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. W B Saunders Co. (2005) ISBN:0721601871

- Soft Tissue Sarcoma Stages. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/soft-tissue-sarcoma/detection-diagnosis-staging/staging.html

- Adjuvant chemotherapy for localised resectable soft-tissue sarcoma of adults: meta-analysis of individual data. Sarcoma Meta-analysis Collaboration. Lancet, 350(9092): 1647-54, 1997.

- Leyvraz, S.; Bacchi, M.; Cerny, T.; Lissoni, A.; Sessa, C.; Bressoud, A.; and Hermann, R.: Phase I multicenter study of combined high-dose ifosfamide and doxorubicin in the treatment of advanced sarcomas. Swiss Group for Clinical Research (SAKK). Ann Oncol, 9(8): 877-84, 1998.

- Midis, G. P.; Pollock, R. E.; Chen, N. P.; Feig, B. W.; Murphy, A.; Pollack, A.; and Pisters, P. W.: Locally recurrent soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities. Surgery, 123(6): 666-71, 1998.

- Billingsley, K. G.; Burt, M. E.; Jara, E.; Ginsberg, R. J.; Woodruff, J. M.; Leung, D. H.; and Brennan, M. F.: Pulmonary metastases from soft tissue sarcoma: analysis of patterns of diseases and postmetastasis survival. Ann Surg, 229(5): 602-10; discussion 610-2, 1999.

- Kearney M.M., Soule E.H., Ivins J.C. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: a retrospective study of 167 cases. Cancer. 1980;45(January (1):167–178.

- Coindre, J. M. et al.: Prognostic factors in adult patients with locally controlled soft tissue sarcoma. A study of 546 patients from the French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group. J Clin Oncol, 14(3): 869-77, 1996.

- Gaynor, J. J.; Tan, C. C.; Casper, E. S.; Collin, C. F.; Friedrich, C.; Shiu, M.; Hajdu, S. I.; and Brennan, M. F.: Refinement of clinicopathologic staging for localized soft tissue sarcoma of the extremity: a study of 423 adults. J Clin Oncol, 10(8): 1317-29, 1992.

- Pisters, P. W.; Leung, D. H.; Woodruff, J.; Shi, W.; and Brennan, M. F.: Analysis of prognostic factors in 1,041 patients with localized soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. J Clin Oncol, 14(5): 1679-89, 1996.

- Salo, J. C.; Lewis, J. J.; Woodruff, J. M.; Leung, D. H.; and Brennan, M. F.: Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the extremity. Cancer, 85(8): 1765-72, 1999.

- Ahlén J, Enberg U, Larsson C, et al. Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma, Aggressive Fibromatosis and Benign Fibrous Tumors Express mRNA for the Metalloproteinase Inducer EMMPRIN and the Metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MT1-MMP. Sarcoma. 2001;5(3):143-149. doi:10.1080/13577140120048601 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2408369/pdf/SRCM-05-143.pdf