What is maltose

Maltose or malt sugar is the least common disaccharide that is derived from hydrolysis by enzymes (α-amylase and β-amylase) of starch in nature. Maltose is present in germinating grain, in a small proportion in corn syrup, and forms on the partial hydrolysis of starch. Maltose has a sweet taste, but is only about 30-60% as sweet as sugar, depending on the concentration 1. A 10% solution of maltose is 35% as sweet as sucrose (table sugar) 2. Maltose is used as a sweetening agent and fermentable intermediate in brewing. There is no specific dietary requirements exist for maltose.

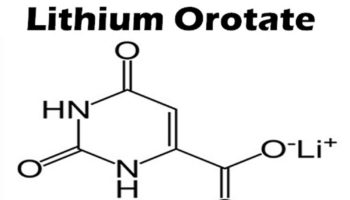

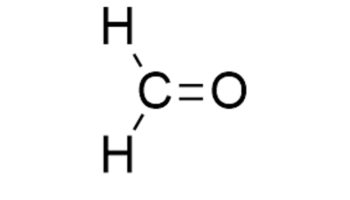

Maltose is a disaccharide formed from two units of glucose joined together with an glycosidic bond (see Figure 1 below). Maltose is broken down by the maltase enzyme, which catalyses the hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond, into two glucose molecules. Maltose is a reducing sugar 3 because the ring of one of the two glucose units can open to present a free aldehyde group; the other one cannot because of the nature of the glycosidic bond. The results of this study 4 indicate that the utilization of circulating maltose elicits similar metabolic effects as glucose. The change in serum maltose after infusion was not accompanied by a significant elevation of glucose, suggesting that extracellular hydrolysis of maltose to glucose is minimal. Since human serum contains almost no maltose activity 5, it is conceivable that maltose enters tissue cells intact and is subsequently metabolized.

Beer is made from four basic building blocks: water, malted barley, and hops. Malting is a process of bringing grain to the point of its highest possible starch content by allowing it to begin to sprout roots and take the first step to becoming a photosynthesizing plant. At the point when the maximum starch content is reached, the seed growth is stopped by heating the grain to a temperature that stops growth but allows an important natural enzyme diastase to remain active. Barley, once “malted” is very high in the type of starches that an enzyme called diastase (found naturally on the surface of the grain, just under the husk) can convert starch quite easily into the disaccharide called maltose. Maltose sugar is then fermented or metabolized by the yeasts to create carbon dioxide and ethyl alcohol.

In humans, maltose is broken down by various maltase enzymes, providing two glucose molecules which can be further processed: either broken down to provide energy, or stored as glycogen. The lack of the sucrase-isomaltase enzyme in humans causes sucrose intolerance, but because there are four different maltase enzymes, complete maltose intolerance is extremely rare 6.

Congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency is a disorder that affects a person’s ability to digest certain sugars and it is characterized by the deficiency or absence of the enzymes sucrase and isomaltase. People with with congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency cannot break down the sugars sucrose and maltose and other compounds made from these sugar molecules (carbohydrates). Congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency usually becomes apparent after an infant is weaned and starts to consume fruits, juices, and grains. After ingestion of sucrose or maltose, an affected child will typically experience stomach cramps, bloating, excess gas production, and diarrhea. These digestive problems can lead to failure to gain weight and grow at the expected rate (failure to thrive) and malnutrition. Most affected children are better able to tolerate sucrose and maltose as they get older. The prevalence of congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency is estimated to be 1 in 5,000 people of European descent. This condition is much more prevalent in the native populations of Greenland, Alaska, and Canada, where as many as 1 in 20 people may be affected.

Affected infants develop symptoms soon after they first ingest sucrose, as found in modified milk formulas, fruits, or starches. Symptoms may include explosive, watery diarrhea resulting in abnormally low levels of body fluids (dehydration), abdominal swelling (distension), and/or abdominal discomfort. In addition, some affected infants may experience malnutrition, resulting from malabsorption of essential nutrients, and/or a delay in growth and weight gain (failure to thrive), resulting from nutritional deficiencies. In some cases, individuals may exhibit irritability; colic; abrasion and/or irritation (excoriation) of the skin on the buttocks as a result of prolonged diarrhea episodes; and/or vomiting. Symptoms of this disorder vary among affected individuals. Symptoms are usually more severe in infants and young children than in adults.

Symptoms of congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency may be absent in an affected infant who is breast-fed or who is on a lactose-only formula; however, as soon as sucrose is introduced into the diet through fruit juices, solid food, medications, and/or other sources, symptoms may rapidly develop. Intolerance to starch may disappear within the first few months or years of life while sucrose intolerance, responsible for most of the symptoms of this disorder, often improves as the affected child ages, exhibiting only occasional or mild symptoms in adulthood. In some cases, symptoms may not be manifested until the onset of puberty.

Symptoms exhibited in infants and young children are usually more pronounced than those of the affected adults because the diet of younger individuals often includes a higher carbohydrate intake. In addition, the time it takes for intestinal digestion is less in infants or young children. In some cases, the development of kidney stones (renal calculi) may be associated with congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency.

Treatment of congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency focuses on dietary management through a low-sucrose or sucrose-free diet. In addition, a low-starch or starch-free diet is advised in some cases, especially in the first few years of life. Some affected individuals may show signs of sucrose tolerance during the second decade of life, but many others may exhibit a life-long sucrose intolerance. Individuals affected with this disorder may benefit from ingesting fresh baker’s yeast, which exhibits sucrase activity, after sucrose ingestion. Researchers suggest that the yeast be taken on a full stomach as sucrase activity is much more effective when the gastric juices are diluted.

The orphan drug sacrosidase oral solution (Sucraid) has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of congenital sucrose isomaltose malabsorption. This oral solution is an enzyme replacement therapy that contains the enzyme sucrase (sacrosidase), obtained from baker’s yeast and glycerin. Sucraid has been found to relieve many of the symptoms associated with sucrose ingestion by individuals with this disorder. Sacrosidase oral solution is manufactured by QOL Medical, LLC.

Genetic counseling is recommended for affected individuals and their families. Other treatment is symptomatic and supportive. For example, fluid and electrolyte replacement after episodes of diarrhea may be indicated to stave off dehydration and/or other associated symptoms.

A team approach for infants with congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency may be of benefit and may include pediatricians, physicians who diagnose and treat disorders of the digestive tract (gastroenterologists), specialists who will assess and plan a diet that best achieves proper growth and development (nutritionists), special social support, and other medical services.

Figure 1. Maltose

Is maltose a monosaccharide?

No. Maltose is a disaccharide formed from two units of glucose joined together with an glycosidic bond.

Is maltose a reducing sugar?

Yes, Maltose is a reducing sugar 3 because the ring of one of the two glucose units can open to present a free aldehyde group; the other one cannot because of the nature of the glycosidic bond.

Where is maltose found?

Maltose is a component of malt, a substance which is obtained in the process of allowing grain to soften in water and germinate. It is also present in highly variable quantities in partially hydrolysed starch products like maltodextrin, corn syrup and acid-thinned starch.

Not many traditional foods are naturally high in maltose. When starchy foods such as cereal grains, corn, potatoes, legumes, nuts and some fruits and vegetables are digested, maltose results. When you cook these foods, the maltose content increases. For example, raw sweet potatoes don’t have any maltose, but cooked sweet potatoes contain approximately 11 grams of maltose per cup. Maltose is also found in molasses, which is a sweet product that gives a distinct flavor to baked goods. There are also some malted beverages that are served as a hot chocolate-like product with milk, or as a malted milkshake.

Natural maltose foods (from highest maltose content to low)

- Sweet potato, cooked, baked in skin, with salt [Sweetpotato]. Maltose: 14590mg

- Sweet potato, cooked, boiled, without skin [Sweetpotato]. Maltose: 8791mg

- Sweet potato, cooked, boiled, without skin, with salt [Sweetpotato]. Maltose: 8791mg

- Sweet potato, cooked, baked in skin, without salt [Sweetpotato]. Maltose: 6933mg

- Prairie Turnips, boiled (Northern Plains Indians). Maltose: 5473mg

- Spelt, uncooked. Maltose: 3047mg

- Edamame, frozen, unprepared. Maltose: 2073mg

- Edamame, frozen, prepared. Maltose: 1557mg

- Broccoli, raw. Maltose: 1235mg

- Tomato products, canned, paste, with salt added. Maltose: 683mg

- Tomato products, canned, paste, without salt added. Maltose: 683mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, cooked, boiled, drained, with salt. Maltose: 611mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, cooked, boiled, drained, without salt. Maltose: 611mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, canned, whole kernel, drained solids. Maltose: 543mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, frozen, kernels, cut off cob, boiled, drained, with salt. Maltose: 430mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, frozen, kernels on cob, cooked, boiled, drained, with salt. Maltose: 430mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, frozen, kernels on cob, cooked, boiled, drained, without salt. Maltose: 430mg

- Peas, green, cooked, boiled, drained, with salt. Maltose: 429mg

- Peas, green, cooked, boiled, drained, without salt. Maltose: 429mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, frozen, kernels on cob, unprepared. Maltose: 428mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, frozen, kernels cut off cob, boiled, drained, without salt. Maltose: 420mg

- Peas, green, raw. Maltose: 420mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, raw. Maltose: 419mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, frozen, kernels cut off cob, unprepared. Maltose: 386mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, canned, vacuum pack, no salt added. Maltose: 329mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, canned, vacuum pack, regular pack. Maltose: 329mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, canned, brine pack, regular pack, solids and liquids. Maltose: 313mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, canned, no salt added, solids and liquids. Maltose: 313mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, canned, cream style, no salt added. Maltose: 306mg

- Corn, sweet, yellow, canned, cream style, regular pack. Maltose: 306mg

- Potatoes, mashed, dehydrated, flakes without milk, dry form. Maltose: 282mg

- Peas, green, canned, no salt added, solids and liquids. Maltose: 264mg

- Peas, green, canned, regular pack, solids and liquids. Maltose: 264mg

- Peas, green, canned, no salt added, drained solids. Maltose: 261mg

- Peas, green, frozen, cooked, boiled, drained, with salt. Maltose: 256mg

- Peas, green, frozen, cooked, boiled, drained, without salt. Maltose: 256mg

- Peas, green, frozen, unprepared. Maltose: 208mg

- Cucumber, with peel, raw. Maltose: 133mg

- Potatoes, mashed, dehydrated, prepared from flakes without milk, whole milk and butter added. Maltose: 124mg

- Peas, green (includes baby and lesuer types), canned, drained soilds, unprepared. Maltose: 116mg

- Cabbage, raw. Maltose: 80mg

- Spinach souffle. Maltose: 35mg

- Potato pancakes. Maltose: 22mg

- Belitz, H.-D.; Grosch, Werner; Schieberle, Peter (2009-01-15). Food Chemistry. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 863. ISBN 9783540699330

- Spillane, W. J. (2006-07-17). Optimizing Sweet Taste in Foods. Woodhead Publishing. p. 271. ISBN 9781845691646.

- Fruton, Joseph S (1999). Proteins, Enzymes, Genes: The Interplay of Chemistry and Biology. Chelsea, Michigan: Yale University Press. p. 144. ISBN 0300153597

- The Metabolism of Circulating Maltose in Man. The Journal of Clinical Investigation Volume 50, 1971. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC292018/pdf/jcinvest00194-0034.pdf

- Weser, E., and M. H. Sleisenger. 1967. Metabolism of circulating disaccharides in man and the rat. J. Clin. Invest. 46: 499.

- Whelan, W. J.; Cameron, Margaret P. (2009-09-16). Control of Glycogen Metabolism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 60. ISBN 9780470716885.