What is mantle cell lymphoma

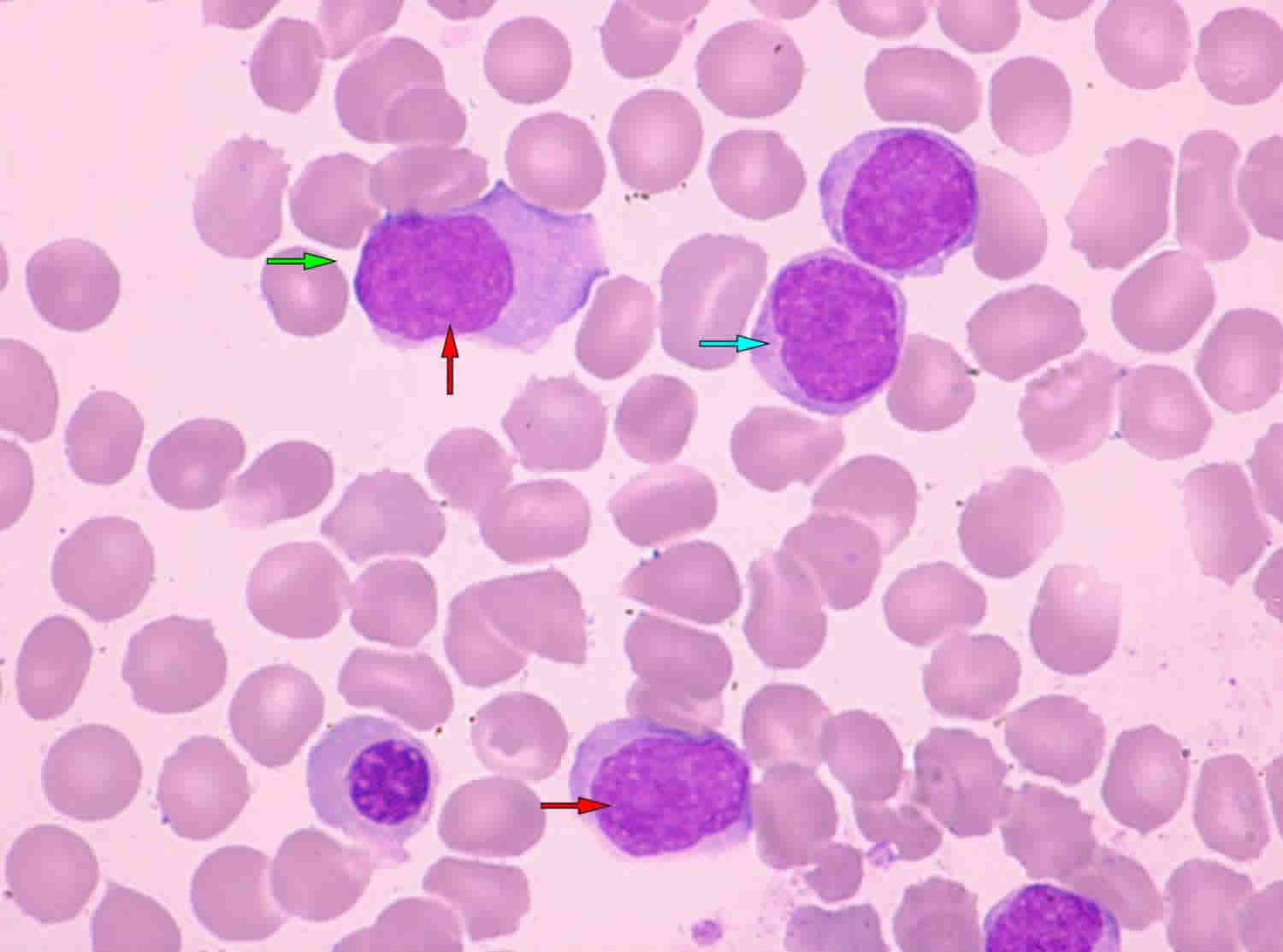

Mantle Cell lymphoma is a rare typically aggressive (fast-growing) type of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma that arises from cells originating in the “mantle zone” 1. Mantle cell lymphoma is a mature B-cell neoplasm usually composed of monomorphic small to medium-sized lymphoid cells with irregular nuclear contours 2. Most people with mantle cell lymphoma are diagnosed with aggressive, widespread disease (stage 3 or 4). Unlike some other types of aggressive lymphomas, however, mantle cell lymphoma is rarely curable with current therapies 3. Even if the initial treatment works, the disease comes back in virtually all patients 3. Mantle cell lymphoma accounts for roughly 6 percent of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases in the United States.

Lymphoma is the most common blood cancer. The body has two main types of lymphocytes that can develop into lymphomas: B lymphocytes (B cells) and T lymphocytes (T cells). Lymphoma occurs when cells of the immune system called lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, grow and multiply uncontrollably. Cancerous lymphocytes can travel to many parts of the body, including the lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow, blood, or other organs, and form a mass called a tumor.

Mantle cell lymphoma affects the B cells (B lymphocytes). Mantle cell lymphoma develops in the part of the lymph node called the mantle zone. The abnormal B lymphocytes start to collect in the lymph nodes or body organs. They can then form tumors and begin to cause problems within the lymphatic system or the organ where they are growing.

There are several variants of Mantle cell lymphoma 2:

- Blastoid: An aggressive variant where cells resemble lymphoblasts with dispersed chromatin and a high mitotic rate.

- Pleomorphic: An aggressive variant where cells are pleomorphic, but many are large with oval to irregular nuclear contours, generally pale cytoplasm, and other prominent nucleoli in at least some of the cells.

- Small-cell: Cells are small round lymphocytes with more clumped chromatin, either admixed or predominant, mimicking a small lymphocytic lymphoma

- Marginal zone-like: There are prominent foci of cells with abundant pale cytoplasm resembling marginal zone or monocytoid B cells, mimicking a marginal zone lymphoma, sometimes these paler foci also resemble proliferation centers of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma most often affects men over the age of 60. Mantle cell lymphoma may be aggressive (fast- growing), but it can also behave in a more indolent (slow-growing) fashion in some patients. Mantle cell lymphoma comprises about five percent of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The disease is called “mantle cell lymphoma” because the tumor cells originally come from the “mantle zone” of the lymph node. mantle cell lymphoma is usually diagnosed as a late-stage disease that has typically spread to the gastrointestinal tract and bone marrow.

Frequently, mantle cell lymphoma is diagnosed at a later stage of disease and in most cases involves the gastrointestinal tract and bone marrow.

Overproduction of a protein called cyclin D1 in the lymphoma cells is found in more than 90 percent of patients with mantle cell lymphoma 4. Identification of excess cyclin D1 from a biopsy is considered a very sensitive tool for diagnosing mantle cell lymphoma. One-quarter to one-half of patients with mantle cell lymphoma also have higher-than-normal levels of certain proteins that circulate in the blood, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and beta-2 microglobulin. Measuring these and other proteins can help physicians determine how aggressive an individual patient’s mantle cell lymphoma is and may guide therapy decisions.

A bone marrow biopsy, computed tomography (CT) scan, or positron emission tomography (PET) scan may be used to determine what areas of the body

are involved by the mantle cell lymphoma.

Figure 1. Locations of major lymph nodes

Figure 2. Functions of lymph nodes in the lymphatic system

Figure 3. Lymph node anatomy

Mantle cell lymphoma biology

While defined as a mature B-non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma has a clinical presentation and natural course that often mimic its more aggressive B-non-Hodgkin Lymphoma counterparts. Patients commonly have lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, bone marrow involvement, and gastrointestinal infiltration at the time of diagnosis 1. Mantle cell lymphoma is classically defined by the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation which juxtaposes the CCDN1 gene encoding cyclin D1 to the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH), resulting in the overexpression of cyclin D1. Alternatively, less-frequent alterations in CCND2 and CCND3, encoding cyclin D2 and D3, respectively, have been identified in mantle cell lymphoma lacking the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocation 5. However, over the past decade, further investigation into the pathogenesis of mantle cell lymphoma has defined other molecular abnormalities that define cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma.

SOX11, a SOX family transcription factor with a role in cell fate and differentiation, has been identified as a reliable diagnostic and prognostic marker of mantle cell lymphoma in both cyclin D1-positive and -negative disease 6. Microarray analyses and protein expression quantification by immunohistochemistry have shown that SOX11 overexpression is an independent molecular feature of mantle cell lymphoma regardless of cyclin D1 status. Furthermore, a complex transcription signature accompanies the overexpression of SOX11. This includes the regulation of the transcription factor PAX5, which is critical for late B-cell differentiation 7. Increased PAX5 levels repress the key transcriptional regulators of plasma cell differentiation BLIMP1, XB1, and IRF4. Supporting this, increased SOX11 expression correlates with an unmutated or minimally mutated IGHV genotype, a marker of germinal center maturation and differentiation into memory B-cells 8. Loss of SOX11 expression, and subsequent downregulation of PAX5, correlates with a hypermutated IGHV genotype, reflective of early steps towards plasma cell differentiation. Clinically, low SOX11 expression correlates with a more indolent and non-nodal leukemic phase presentation, whereas increased SOX11 expression portends a more aggressive phenotype with nodal and extra-nodal sites of involvement. Taken together, the implementation of CCND2, CCND3, SOX11, and IGHV analysis has expanded criteria for the molecular diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma.

Figure 4. Mantle cell lymphoma proposed molecular pathogenesis and progression

[Source 9]Mantle cell lymphoma prognosis

Mantle cell lymphoma is thought to be an aggressive disease in most patients, associated with early relapse and poor long-term survival. Most patients present in Stage III or IV mantle cell lymphoma. Spleen, bone marrow and liver are common metastatic sites.

Patients presenting with peripheral blood, bone marrow and possibly splenic involvement but without adenopathy are reported to have better prognosis.

How long mantle cell lymphoma take to relapse, and how long a second response may last, depends largely on the patient’s response to the initial course of treatment and the biology of their disease, which can vary greatly from patient to patient 3

The mantle cell lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI) incorporates patient age, performance status, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and white blood cell count into a formula to stratify patients as low, intermediate, or high risk; 5-year overall survival for MIPI-low patients was 83% compared with 34% in MIPI-high patients, with a high MIPI score also predicting inferior response to therapy 10. A similar tool, the Biologic mantle cell lymphoma International Prognostic Index, incorporates the Ki-67 proliferation rate, usually readily obtained from pathology specimens, to better identify high-risk disease 11.

Among the various clinical and pathologic factors analyzed in a population-based study reported by the British Columbia Cancer Agency (n=440), non-nodal presentation, defined as patients presenting with lymphocytosis and/or splenomegaly, was the single factor most strongly associated with prolonged time to treatment and excellent overall survival. In this study, median time to treatment was 35 months without a negative impact on overall survival in patients deemed suitable for initial observation. Other characteristics of the observed patients included good performance status, absence of B-symptoms, non-blastoid morphology, and Ki67 percentage of less than 30%. There were no significant differences in the observed versus treatment groups, including in age at diagnosis, sex, leukocyte count, platelet count, stage, TP53 and SOX11 expression by immunohistochemistry, and MIPI risk score 12.

While there are no prospective data guiding observation in patients based on SOX11 or TP53 expression, these are additional variables that can be considered clinically to predict disease course. In the British Columbia study above, P53 positivity was defined as strong nuclear staining and SOX11 was positive if any cells stained positive. A second study by the European mantle cell lymphoma Network sorted patients into groups based on percentage of P53-positive cells (1–10%, 10–50%, and over 50%) and SOX11 cells (0%, 1–10%, and over 10%) by immunohistochemistry 13. In this study, the cohort with over 50% TP53 expression had poorer prognosis, while SOX11 expression was not a reliable prognostic marker, possibly owing to an under-representation of patients with non-nodal disease. Another explanation is a difference in methods to determine SOX11 positivity, as Navarro et al. 8 used a combination of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to measure SOX11 RNA, immunohistochemistry to measure SOX11 protein, and gene expression profiling and observed an improved clinical outcome with low SOX11 expression.

It is important to note that no patients in the above cohorts were observed with the pathologic blastoid variant of mantle cell lymphoma, which continues to be a clinical challenge 14. This group, which comprises less than 20% of total mantle cell lymphoma diagnoses, features medium-sized lymphocytes with indistinct cytoplasm and dispersed chromatin compared with classical-type mantle cell lymphoma with smaller lymphocytes and condensed chromatin. In a subgroup analysis of all modern trials, the patients with blastoid phenotype have inferior survival and remission rates. A further understanding of the disease process in these patients is greatly needed for the development of novel therapies. Thus, when deciding on initial observations, we consider all of the aforementioned disease features and balance this with the patient’s preferences and other comorbidities. It should be remembered that many patients will not behave as their risk features predict, so close monitoring for progression of disease is necessary in all observed patients.

Mantle cell lymphoma life expectancy

Survival: 3-5 years median survival 2.

The median overall survival for the low-risk group was not reached (5-year overall survival of 60%). The median overall survival for the intermediate risk group was 51 months and 29 months for the high risk group 9.

Mantle cell lymphoma symptoms

The symptoms of mantle cell lymphoma are similar to those of most other types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The most common symptom of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is one or more painless swellings in the:

- neck

- armpit

- groin

These swellings are enlarged lymph nodes.

Lymph nodes, also known as lymph glands, are pea-sized lumps of tissue found throughout the body (see Figures 1 to 3). Lymph nodes contain white blood cells that help to fight against infection.

The swelling is caused by a certain type of white blood cell, known as lymphocytes, collecting in the lymph node.

However, it’s highly unlikely you have non-Hodgkin lymphoma if you have swollen lymph nodes, as these glands often swell as a response to infection.

General symptoms (B symptoms). You might have other general symptoms such as:

- Heavy sweating at night

- Fever that come and go with no obvious cause

- Losing a lot of weight (more than one tenth of your total weight) for no known reason

- Unexplained skin rash or itchy skin

Doctors call this group of symptoms B symptoms. Some people with non-Hodgkin lymphoma have these symptoms, but many don’t.

Other symptoms

- Fatigue

- Hepatosplenomegaly (enlarged liver and spleen)

- Lymphocytosis

- Pain in the chest, abdomen, or bones (for no known reason)

- Persistent cough or feeling of breathlessness

Mantle cell lymphoma can spread to the bowel and in rare cases to the stomach. If this happens, it can cause symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain and sickness.

A few people with lymphoma have abnormal cells in their bone marrow when they’re diagnosed. This may lead to:

- Persistent tiredness or fatigue

- An increased risk of infections

- Excessive bleeding – such as nosebleeds, heavy periods and spots of blood under the skin.

Mantle cell lymphoma stages

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Stages

After someone is diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, doctors will try to figure out if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes how much cancer is in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. .

Tests used to gather information for staging can include:

- Physical exam

- Biopsies of enlarged lymph nodes or other abnormal areas

- Blood tests

- Imaging tests, such as PET and CT scans

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy (often but not always done)

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap – this may not need to be done)

In general, the results of imaging tests such as PET or CT scans are the most important when determining the stage of the lymphoma.

Lugano classification

A staging system is a way for members of a cancer care team to sum up the extent of a cancer’s spread. The current staging system for non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in adults is known as the Lugano classification, which is based on the older Ann Arbor system.

The stages are described by Roman numerals I through IV (1-4). Limited stage (I or II) lymphomas that affect an organ outside the lymph system (an extranodal organ) have an E added (for example, stage IIE).

Stage I

Either of the following means the disease is stage I:

- The lymphoma is in only 1 lymph node area or lymphoid organ such as the tonsils (I).

- The cancer is found only in 1 area of a single organ outside of the lymph system (IE).

Stage II

Either of the following means the disease is stage II:

- The lymphoma is in 2 or more groups of lymph nodes on the same side of (above or below) the diaphragm (the thin band of muscle that separates the chest and abdomen). For example, this might include nodes in the underarm and neck area (II) but not the combination of underarm and groin nodes (III).

- The lymphoma is in a group of lymph node(s) and in one area of a nearby organ (IIE). It may also affect other groups of lymph nodes on the same side of the diaphragm.

Stage III

Either of the following means the disease is stage III:

- The lymphoma is in lymph node areas on both sides of (above and below) the diaphragm.

- The lymphoma is in lymph nodes above the diaphragm, as well as in the spleen.

Stage IV

- The lymphoma has spread widely into at least one organ outside the lymph system, such as the bone marrow, liver, or lung.

Bulky disease

This term is often used to describe large tumors in the chest. It is especially important for stage II lymphomas, as bulky disease might need more intensive treatment.

Mantle cell lymphoma treatment

The type of treatment selected for a patient with mantle cell lymphoma depends on multiple factors, including the stage of disease, the age of the patient, and the patient’s overall health. For the subset of patients who do not yet have symptoms and who have a relatively small amount of slow- growing disease, “watchful waiting” may be an acceptable option 15. With this strategy, patients’ overall health and disease are monitored through regular checkup visits and various evaluating procedures, such as laboratory and imaging tests.

Active treatment is started if the patient begins to develop lymphoma-related symptoms or there are signs that the disease is progressing based on testing during follow-up visits.

Mantle cell lymphoma is usually diagnosed once it has spread throughout the body, and the majority of these patients will require treatment. Initial treatment approaches for aggressive mantle cell lymphoma in younger patients include combination chemotherapy, typically in combination with the monoclonal antibody rituximab (Rituxan), as first-line treatment, followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (in which patients receive their own stem cells), though rituximab is not specifically approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for mantle cell lymphoma. Combination chemotherapy containing cytarabine plus the immunotherapeutic monoclonal antibody rituximab are recommended as aggressive induction therapy and are associated with durable remissions in newly diagnosed patients. Consolidation high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell is often utilized to prolong remission in younger, medically fit patients. For older or less fit patients, less intensive chemotherapy followed by a prolonged course of rituximab alone, known as maintenance therapy, is often recommended. A common chemotherapeutic treatment approach used to treat mantle cell lymphoma is called R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). Bendamustine (Treanda) in combination with rituximab is another common first-line treatment option. Several additional intensified chemotherapy combinations are also used in combination with rituximab, particularly in younger patients.

Although allogeneic stem cell transplantation (in which patients receive stem cells from a related or unrelated donor) is very intensive and causes various side effects, including possibly graft-versus- host disease, it may increase response times for selected younger patients whose disease has relapsed (returned after treatment).

Bortezomib (Velcade) is approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Studies with bortezomib show that the drug may be effectively combined with conventional chemotherapy.

Lenalidomide (Revlimid) is another treatment for mantle cell lymphoma approved by the FDA for patients who have relapsed or progressed after two prior therapies, one of which included bortezomib. Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory agent that affects the growth and survival of tumor cells by altering the body’s immune cells. It may be given in combination with rituximab.

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) is approved by the FDA for treatment of mantle cell lymphoma in patients who have received at least one prior therapy and is also used to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia and Waldenström macroglobulinemia. This therapy is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, which stops signals in cancer cells that are responsible for growth and survival.

Treatment options may change as new treatments are discovered and current treatments are improved. Therefore, it is important that patients check with their physician or with the Lymphoma Research Foundation (https://www.lymphoma.org/) for any treatment updates that may have recently emerged.

Follow-up

Patients in remission should have regular visits with a physician who is familiar with their medical history and the treatments they have received. Medical tests (such as blood tests and PET/CT scans) may be required at various times during remission to evaluate the need for additional treatment.

Patients and their caregivers are encouraged to keep copies of all medical records and test results as well as information on the types, amounts, and duration of all treatments received. This documentation will be important for keeping track of any effects resulting from treatment or potential disease recurrences.

References- Schieber M, Gordon LI, Karmali R. Current overview and treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. F1000Research. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1136. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14122.1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6069726/

- Mantle cell lymphoma. https://seer.cancer.gov/seertools/hemelymph/51f6cf57e3e27c3994bd5357/

- Acalabrutinib Receives FDA Approval for Mantle Cell Lymphoma. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2017/acalabrutinib-fda-mantle-cell-lymphoma

- Mantle Cell Lymphoma. https://www.lymphoma.org/aboutlymphoma/nhl/mcl/

- Salaverria I, Royo C, Carvajal-Cuenca A, et al. : CCND2 rearrangements are the most frequent genetic events in cyclin D1 – mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2013;121(8):1394–402. 10.1182/blood-2012-08-452284

- Mozos A, Royo C, Hartmann E, et al. : SOX11 expression is highly specific for mantle cell lymphoma and identifies the cyclin D1-negative subtype. Haematologica. 2009;94(11):1555–62. 10.3324/haematol.2009.010264

- Vegliante MC, Palomero J, Pérez-Galán P, et al. : SOX11 regulates PAX5 expression and blocks terminal B-cell differentiation in aggressive mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2013;121(12):2175–85. 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438937

- Navarro A, Clot G, Royo C, et al. : Molecular subsets of mantle cell lymphoma defined by the IGHV mutational status and SOX11 expression have distinct biologic and clinical features. Cancer Res. 2012;72(20):5307–16. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1615

- Vose, J.M. (2017). Mantle cell lymphoma: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and clinical management. American journal of hematology, 92 8, 806-813.

- Hoster E, Klapper W, Hermine O, et al. : Confirmation of the mantle-cell lymphoma International Prognostic Index in randomized trials of the European Mantle-Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(13):1338–46. 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.2466

- Hoster E, Rosenwald A, Berger F, et al. : Prognostic Value of Ki-67 Index, Cytology, and Growth Pattern in Mantle-Cell Lymphoma: Results From Randomized Trials of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1386–94. 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.8387

- Abrisqueta P, Scott DW, Slack GW, et al. : Observation as the initial management strategy in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2489–95. 10.1093/annonc/mdx333

- Aukema SM, Hoster E, Rosenwald A, et al. : Expression of TP53 is associated with the outcome of MCL independent of MIPI and Ki-67 in trials of the European MCL Network. Blood. 2018;131(4):417–20. 10.1182/blood-2017-07-797019

- Bernard M, Gressin R, Lefrère F, et al. : Blastic variant of mantle cell lymphoma: A rare but highly aggressive subtype. Leukemia. 2001;15(11):1785–91. 10.1038/sj.leu.2402272

- Mantle Cell Lymphoma. https://www.lymphoma.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/LRF_FACTSHEET_MANTLE_CELL_LYMPHOMA_MCL.pdf