What is mechanical ventilation

Mechanical ventilation is a life support treatment. A mechanical ventilator is a machine that helps people breathe when they are not able to breathe enough on their own. The mechanical ventilator is also called a ventilator, respirator, or breathing machine. Most patients who need support from a ventilator because of a severe illness are cared for in a hospital’s intensive care unit (ICU). People who need a ventilator for a longer time may be in a regular unit of a hospital, a rehabilitation facility, or cared for at home.

Mechanical ventilation is a machine that supports breathing. These machines mainly are used in hospitals.

Ventilators most often are used:

- During surgery if you’re under anesthesia (that is, if you’re given medicine that makes you sleep and/or causes a loss of feeling)

- If a disease or condition impairs your lung function

Mechanical ventilators:

- Get oxygen into the lungs.

- Remove carbon dioxide from the body. (Carbon dioxide is a waste gas that can be toxic.)

- Help people breathe easier.

- Breathe for people who have lost all ability to breathe on their own.

A ventilator often is used for short periods, such as during surgery when you’re under general anesthesia. The term “anesthesia” refers to a loss of feeling and awareness. General anesthesia temporarily puts you to sleep. The medicines used to induce anesthesia can disrupt normal breathing. A ventilator helps make sure that you continue breathing during surgery.

A ventilator also may be used during treatment for a serious lung disease or other condition that affects normal breathing.

Some people may need to use ventilators long term or for the rest of their lives. In these cases, the machines can be used outside of the hospital—in long-term care facilities or at home.

A ventilator doesn’t treat a disease or condition. It’s used only for life support.

Mechanical ventilation is a “life-sustaining treatment”. It is a treatment that can prolong life. It may be needed for only a short time. However, some people cannot be weaned off the ventilator and do not want to stay on the machine. Other people who know they have a very severe lung or health problem may not even want to use a ventilator at all. That is because the ventilator cannot fix their underlying condition.

Some people have very specific thoughts about if and when they should be placed on a ventilator. Although the healthcare team helps people and their families make tough decisions about the end of life, it is the person him or herself who has the final say. If a person cannot talk or communicate decisions, the healthcare team will talk with his or her legally authorized representative (usually a parent, wife or husband, adult child, or next of kin).

It is important that you talk with your family members and your health care provider about using a ventilator and what you would like to happen in different situations. The more clearly you explain your values and choices to friends, loved ones and the heatlhcare team, the easier it makes it for them to follow your wishes if and when you are unable to make decisions yourself. Advance directives are ways to also put your wishes in writing to share with others. In the hospital, nurses, doctors and social workers can provide information about an advance directive form. You can also obtain information on advance directives from your primary care provider, state Attorney General’s office, public health department, or organizations such as Aging With Dignity (https://agingwithdignity.org/) and PREPARE for Your Care (https://prepareforyourcare.org).

Basics of mechanical ventilation

The ventilator is connected to the person through a tube (endotracheal or ET tube) that is placed into the mouth or nose and down into the windpipe. When the health care provider places the endotracheal tube into the person’s windpipe, it is called an intubation. Some people go through surgery to have a hole place in their neck and a tube (tracheostomy or “trach” tube) is connected through that hole. The trach tube is able to stay in as long as needed. At times a person can talk with a trach tube in place by using a special adapter called a speaking valve. The ventilator blows gas (air plus oxygen as needed) into a person’s lungs. It can help a person by doing all of the breathing or just assisting the person’s breathing. The ventilator can deliver higher levels of oxygen than delivered by a mask or other devices. The ventilator can also provide what is called positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP). This helps to hold the lungs open so that the air sacs do not collapse. The tube in the windpipe also makes it easier to remove mucus if someone has a weak cough.

Mechanical ventilation itself does not cause pain. Some people don’t like the feeling of having the tube in their mouth or nose. They cannot talk because the tube passes between the vocal cords into the windpipe. They also cannot eat by mouth when this tube is in place. A person may feel uncomfortable as air is pushed into their lungs. Sometimes a person will try to breathe out when the ventilator is trying to push air in. This is working (or fighting) against the ventilator and makes it harder for the ventilator to help.

People on ventilators may be given medicines (sedatives or pain controllers) to make them feel more comfortable. These medicines may also make them sleepy. Sometimes, medications that temporarily prevent muscle movement (neuromuscular blocking agents) are used to allow a person to breathe with the ventilator. These agents are typically used when a person has very severe lung injury; they are stopped as soon as possible and always before ventilator support is removed.

Mechanical ventilation patient monitoring

Patients on mechanical ventilation will be hooked up to a monitor that measures heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation (“O2 sats”). Other tests that may be done include chest-x-rays and blood drawn to measure oxygen and carbon dioxide (“blood gases”). Members of the health care team (including doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists) will use this information to assess the patient’s status and make adjustments to the ventilator if necessary.

Mechanical ventilation indications

Mechanical ventilation is used:

- To get oxygen into the lungs and body

- To help the body get rid of carbon dioxide through the lungs

- To ease the work of breathing—Some people can breath on their own, but it is very hard. They feel short of breath and uncomfortable.

- To breathe for a person who is not breathing because of injury to the nervous system, like the brain or spinal cord, or who has very weak muscles.

Many factors affect the decision to begin mechanical ventilation. Because no mode of mechanical ventilation can cure a disease process, the patient should have a correctable underlying problem that can be resolved with the support of mechanical ventilation. This intervention should not be started without thoughtful consideration because intubation and positive-pressure ventilation are not without potentially harmful effects.

Mechanical ventilation is indicated when the patient’s spontaneous ventilation is inadequate to sustain life. In addition, it is indicated as a measure to control ventilation in critically ill patients and as prophylaxis for impending collapse of other physiologic functions. Physiologic indications include respiratory or mechanical insufficiency and ineffective gas exchange.

Common indications for mechanical ventilation include the following:

- Bradypnea or apnea with respiratory arrest 1

- Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Tachypnea (respiratory rate >30 breaths per minute)

- Vital capacity less than 15 mL/kg

- Minute ventilation greater than 10 L/min

- Arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) with a supplemental fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) of less than 55 mm Hg

- Alveolar-arterial gradient of oxygen tension (A-a DO2) with 100% oxygenation of greater than 450 mm Hg

- Clinical deterioration

- Respiratory muscle fatigue

- Obtundation or coma

- Hypotension

- Acute partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) greater than 50 mm Hg with an arterial pH less than 7.25

- Neuromuscular disease

The trend of these values should influence clinical judgment. Increasing severity of illness should prompt the clinician to consider starting mechanical ventilation.

Types of mechanical ventilation

Non-invasive mechanical ventilation

A mask that has been sized correctly for you is placed on your face. It covers either your nose or your nose and mouth. A machine then helps your breathing. This helps decrease the work of breathing and gives you more oxygen.

Non-invasive mechanical ventilation may be used if you are finding it hard to breathe but you’re still able to breathe on your own.

Invasive mechanical ventilation

A breathing tube (endotracheal or ET tube) is placed in your mouth. The tube goes into your windpipe. A machine then helps with your breathing. In severe cases, the machine may breathe for you while your lung function improves. Medicines are given to help keep you as comfortable as possible. The breathing tube is removed when you are better and can breathe on your own.

Your doctor may give you invasive mechanical ventilation if:

- You have severe trouble breathing or you can’t breathe on your own.

- You are confused or can’t think clearly.

- You have other health problems that make it more likely that non-invasive ventilation won’t work.

- You have received non-invasive ventilation but it hasn’t helped your breathing.

Talk with your doctor and your family ahead of time about what kind of treatment you want for your condition.

Mechanical ventilation settings

Modern ventilators are classified by their method of cycling from the inspiratory phase to the expiratory phase. That is, they are named after the parameter that signals the termination of the positive-pressure inspiration cycle of the machine. The signal to terminate the inspiratory activity of the machine is either a preset volume (for a volume-cycled ventilator), a preset pressure limit (for a pressure-cycled ventilator), or a preset time factor (for a time-cycled ventilator).

Volume-cycled ventilation is the most common form of ventilator cycling used in adult medicine because it provides a consistent breath-to-breath tidal volume. Termination of the delivered breath is signaled when a set volume leaves the ventilator.

Positive-pressure ventilation means that airway pressure is applied at the patient’s airway through an endotracheal or tracheostomy tube. The positive nature of the pressure causes the gas to flow into the lungs until the ventilator breath is terminated. As the airway pressure drops to zero, elastic recoil of the chest accomplishes passive exhalation by pushing the tidal volume out.

Today, negative-pressure ventilation is used in only a few situations. The cuirass, or shell unit, allows negative pressure to be applied only to the patient’s chest by using a combination of a form-fitted shell and a soft bladder. It provides a suitable and attractive option for patients with neuromuscular disorders, especially those with residual muscular function, because it does not require a tracheostomy with its inherent problems.

Summary of initial ventilator setup

Initial settings for ventilation may be summarized as follows:

- Assist-control mode

- Tidal volume set depending on lung status – Normal = 12 mL/kg ideal body weight; COPD = 10 mL/kg ideal body weight; ARDS = 6-8 mL/kg ideal body weight

- Rate of 10-12 breaths per minute

- FIO2 of 100%

- Sighs rarely needed

- PEEP only as indicated after first arterial blood gas determination, ie, shunt greater than 25%

- Inability to oxygenate with an FIO2 less than 60%

Mechanical ventilation modes

After deciding to start positive-pressure ventilation with a volume-cycled ventilator, the clinician must now select the safest initial mode of machine operation.

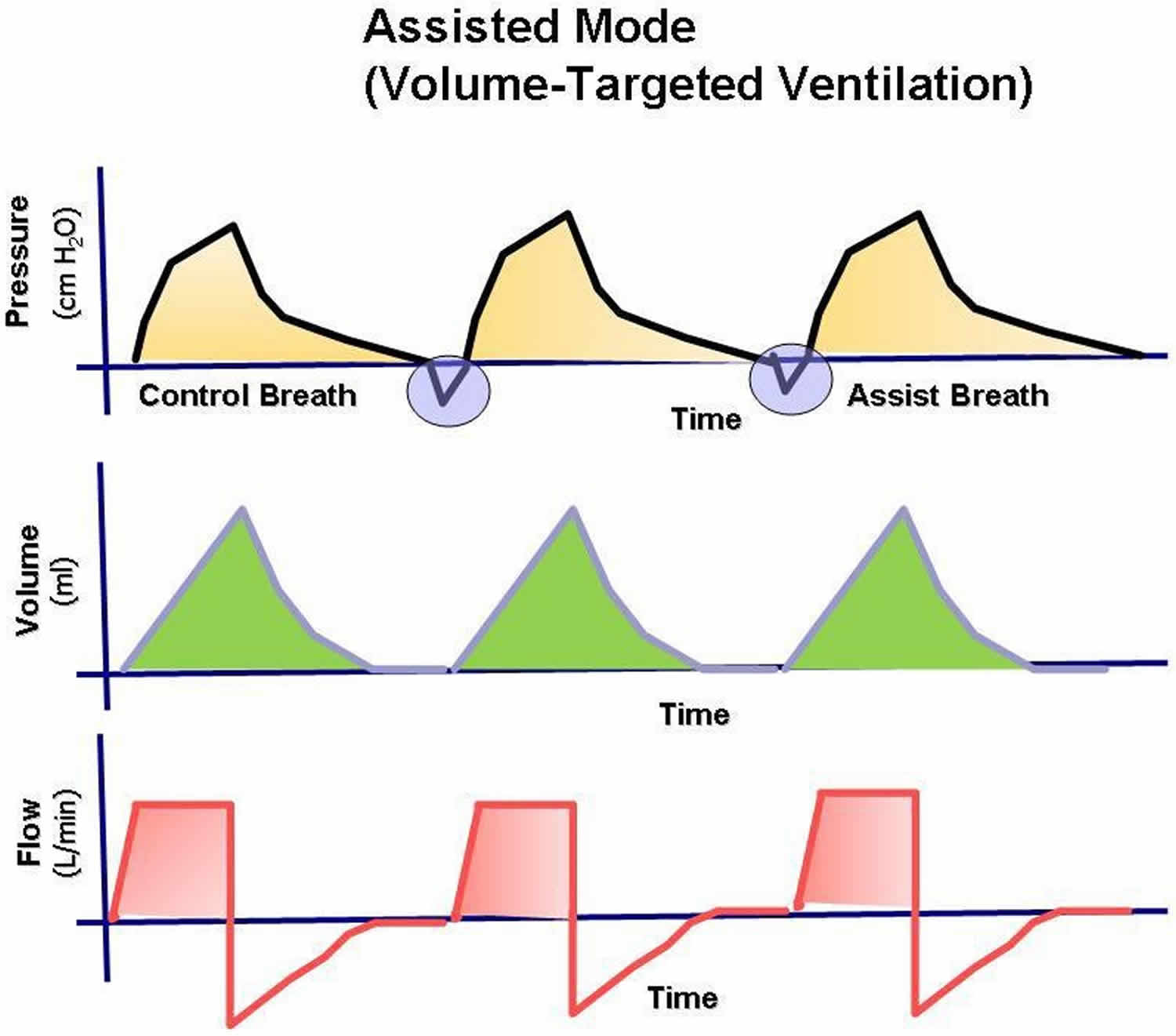

In most circumstances, the initial mode of ventilation should be the assist-control mode, in which a tidal volume and rate are preset and guaranteed. The patient can affect the frequency and timing of the breaths. If the patient makes an inspiratory effort, the ventilator senses a decrease in the circuit pressure and delivers the preset tidal volume. In this way, the patient can dictate a comfortable respiratory pattern and may trigger additional machine-assisted breaths above the set rate. If the patient does not initiate inspiration, the ventilator automatically delivers the preset rate and tidal volume, ensuring minimum minute ventilation. In the assist-control mode, the work of breathing is reduced to the amount of inspiration needed to trigger the inspiratory cycle of the machine. This trigger is adjusted by setting the sensitivity of the machine to the degree of pressure decrease desired in the circuit (Figure 1).

Assist-control differs from controlled ventilation because the patient can trigger the ventilator to deliver a breath and, thereby, adjust their minute ventilation.

Figure 1. Assisted Mode mechanical ventilation

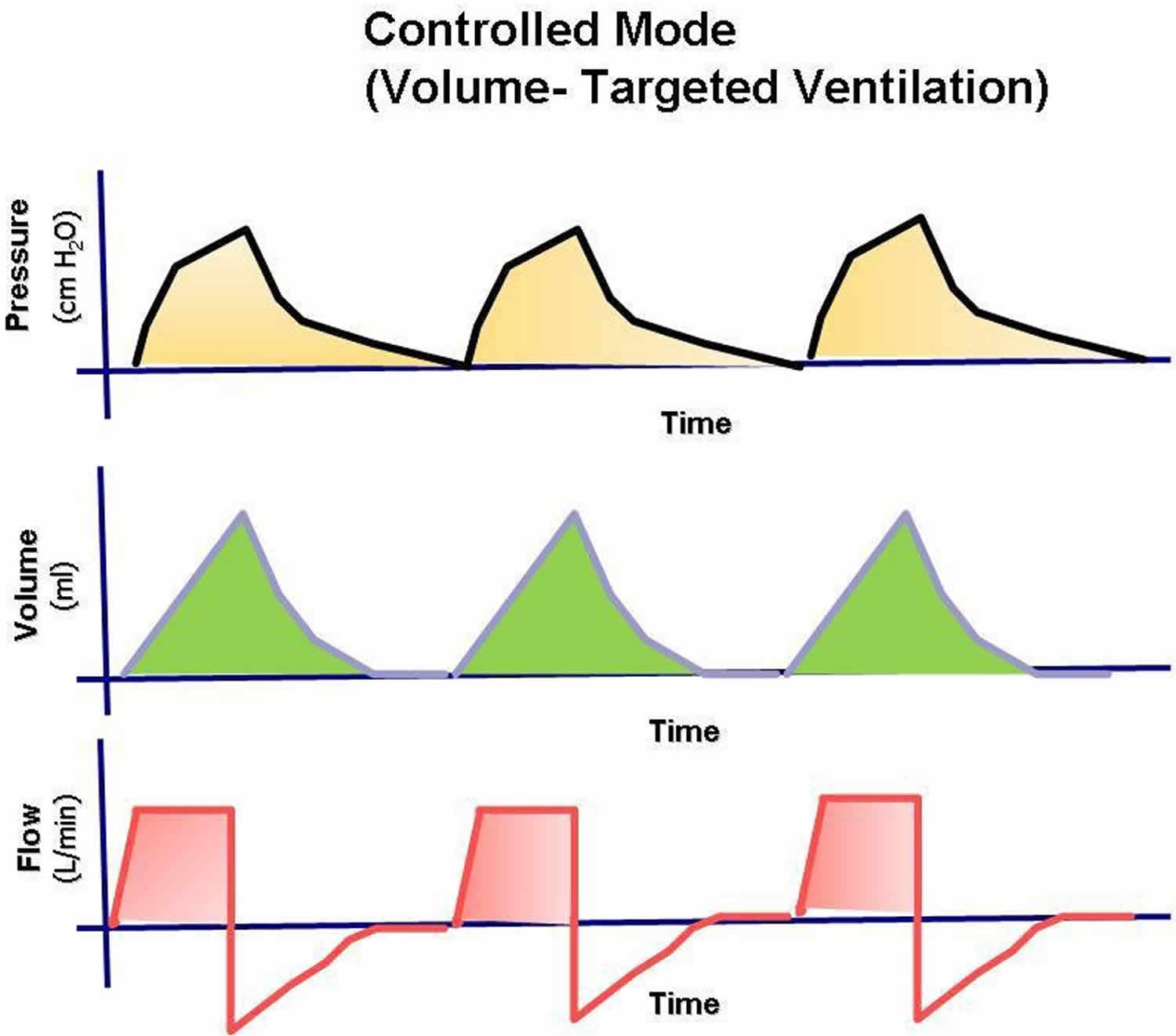

In controlled ventilation, the patient receives only breaths initiated by the ventilator at the preset rate (Figure 2). Although the work of breathing is not eliminated, controlled mode mechanical ventilation gives the respiratory muscles the greatest amount of rest because the patient needs only to create enough negative pressure to trigger the machine. An added advantage is that the patient can achieve the required minute ventilation by triggering additional breaths above the set back-up rate.

In controlled ventilation, the patient receives only breaths initiated by the ventilator at the preset rate (Figure 2). Although the work of breathing is not eliminated, controlled mode mechanical ventilation gives the respiratory muscles the greatest amount of rest because the patient needs only to create enough negative pressure to trigger the machine. An added advantage is that the patient can achieve the required minute ventilation by triggering additional breaths above the set back-up rate.Figure 2. Controlled Mode mechanical ventilation

In most cases, a minute ventilation that provides a reasonable pH based on the respiratory rate is determined by the patient’s chemoreceptors and stretch receptors. The respiratory center in the central nervous system receives input from the chemical receptors (arterial blood gas tensions) and neural pathways that sense the mechanical work of breathing (mechanoreceptors). The respiratory rate and respiratory pattern are the result of input from these chemoreceptors and mechanical receptors, which allow the respiratory center to regulate gas exchange. In the assist-control mode, this process is accomplished with the minimum work of breathing.

A second possible advantage of this mode of mechanical ventilation is that cycling the ventilator into the inspiratory phase maintains normal ventilatory activity and, therefore, prevents atrophy of the respiratory muscles.

A potential disadvantage of the assist-control mode is respiratory alkalosis in a small subset of patients whose respiratory drive supersedes the chemoreceptors and mechanical receptors. Patients with a potential for alveolar hyperventilation and hypocapnia in the assist-control mode include those with end-stage liver disease, those in the hyperventilatory stage of sepsis, and those with head trauma. These conditions are typically identified with the first arterial blood gas results, and the assist-control mode of ventilation can then be changed to an alternate mode.

Another possible disadvantage is the potential for serial preset positive-pressure breathes to retard venous return to the right side of heart and to affect global cardiac output. Nevertheless, the assist-control mode may be the safest initial choice for mechanical ventilation. It may be switched to another option if hypotension or hypocarbia are evident from the first arterial blood gas results.

Alternative Modes of Mechanical Ventilation

In the last 2 decades, several modes of ventilation have emerged from the successful merging of the ventilator and computer technologies. Staying abreast of emerging ventilator modifications can be a formidable and ongoing challenge for physicians.

Dual-control ventilation modes were designed to combine the advantages of volume-control ventilation (guaranteed minute ventilation) with pressure-control ventilation (rapid, variable flow at a preset or limited peak airway pressure). These dual-control modes attempt to increase the safety and comfort of mechanical ventilation. Although these new technologies seem promising, no findings from randomized trials indicate improved patient outcomes (including mortality).

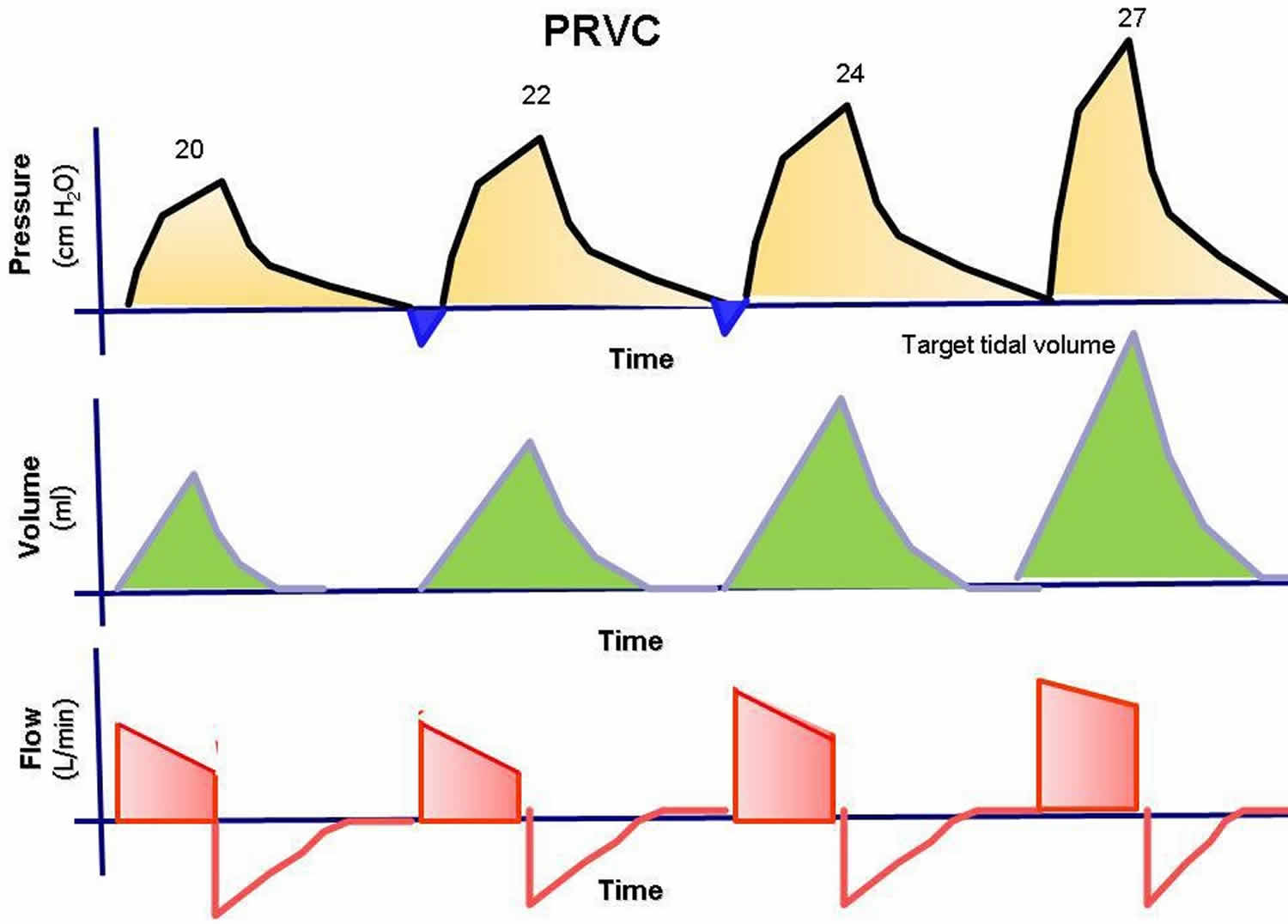

Dual-control, breath-to-breath, pressure-limited, time-cycled ventilation

This mode has been called pressure-regulated volume-control (PRVC), adaptive pressure ventilation, auto-flow, volume-control plus, or variable-pressure control ventilation according to various commercial ventilators. This mode is under the dual control of pressure and volume. The physician presets a desired tidal volume, and the ventilator delivers a pressure-limited (controlled) breath until that preset tidal volume is achieved. The breath is essentially like a conventional pressure-controlled ventilation breath, but the ventilator can guarantee a predetermined minute ventilation.

Breath to breath, the inspiratory pressure is automatically adjusted down or up according to the patient’s lung compliance and/or resistance to deliver a preset tidal volume. The ventilator monitors each breath and compares the delivered tidal volume with the set tidal volume. If the delivered volume is too low, it increases the inspiratory pressure on the next breath. If it is too high, it decreases the inspiratory pressure to the next breath. This adjustment gives the patient the lowest peak inspiratory pressure needed to achieve a preset tidal volume. The advantage of this mode is that it gives the physician the opportunity to deliver a minimum minute ventilation at the lowest peak airway pressures possible.

Figure 3. Pressure-regulated volume-controlled ventilation (PRVC)

Dual-control breath-to-breath, pressure-limited, flow-cycled ventilation

This mode has been called volume-support ventilation (VSV ) or variable-pressure-support according to which ventilator is used. This mode is a combination of pressure support ventilation (PSV) and volume-control ventilation. Like pressure support ventilation (PSV), the patient triggers every breath, controlling his or her own respiratory frequency and inspiratory time. This mode delivers a breath exactly like conventional pressure support ventilation (PSV), but the ventilator can guarantee minute ventilation. The pressure support is automatically adjusted up or down according to the patient’s lung compliance and/or resistance to deliver a preset tidal volume.

This mode is similar to the dual-control breath-to-breath, pressure-limited, time-cycled ventilation except that it is flow cycled, which means that the patient determines the respiratory rate and inspiratory time. The mode cannot be used in a patient who lacks spontaneous breathing effort.

Volume support has also been marketed as a self-weaning mode. Therefore, as the patient’s effort and/or compliance or resistance improve, pressure support is automatically titrated down without the need for input from a physician or therapist.

A number of potential problems can arise. If the patient’s metabolic demand increases, raising the tidal volume, the pressure support decreases to provide less ventilatory support when the patient needs it most. The clinician must be aware that, as the level of pressure support drops, mean airway pressure decreases. This effect may result in hypoxemia. The other concern is that the tidal volume must be correctly set to the patient’s metabolic needs. If the tidal volume is set too high, weaning is delayed. If it is set too low, the work of breathing may be more than what the patient can reasonably accomplish.

Automode and variable support or variable-pressure control

This mode is basically the combination of the 2 modes described above. If the patient has no spontaneous breaths, the ventilator is set up in the pressure-regulated volume-control (PRVC) mode. However, when the patient takes 2 consecutive breaths, the mode is switched to volume-support ventilation (VSV ). If the patient becomes apneic for 12 seconds, the ventilator switches back to pressure-regulated volume-control (PRVC) mode.

Automode and variable support or variable-pressure control was designed for automatic weaning from pressure control to pressure support depending on the patient’s effort. This ventilatory mode can also be used in conventional volume control and volume support. Again, the mode depends on the patient’s effort. To the authors’ knowledge, no randomized trials have been conducted to evaluate this automode, and no evidence suggests that this type of weaning is more effective than conventional weaning.

Dual control within a breath

This mode has been called volume-assured pressure support or pressure augmentation according to various manufacturers. This mode can switch from pressure control to volume control within a single specific breath cycle. After a breath is triggered, rapid and variable flow creates pressure to reach the set level of pressure support. The tidal volume that is delivered from the machine is monitored. If the tidal volume equals the minimum set tidal volume, the patient receives a typical pressure-supported breath, which makes this mode essentially like volume support. However, if the tidal volume is less than the set tidal volume, the ventilator switches to a volume-controlled breath with constant flow rate until the set tidal volume is reached.

One study compared volume-assured pressure support with simple assist-control volume support and showed a 50% reduction in the work of breathing, lowered airway resistance, and lowered intrinsic PEEP. However, because of its complexity, this mode is rarely used.

Automatic tube compensation

This mode is specifically used for weaning and is designed to overcome the resistance of the endotracheal tube by means of continuous calculations. These calculations deal with known resistive coefficients of the artificial airway (size and length), tracheal pressures, and measurement of instantaneous flow. These calculations allow the ventilator to supply the appropriate pressure needed to overcome this resistance throughout the entire respiratory cycle. To the authors’ knowledge, no studies have proven that this mode is any better than spontaneous breathing trials.

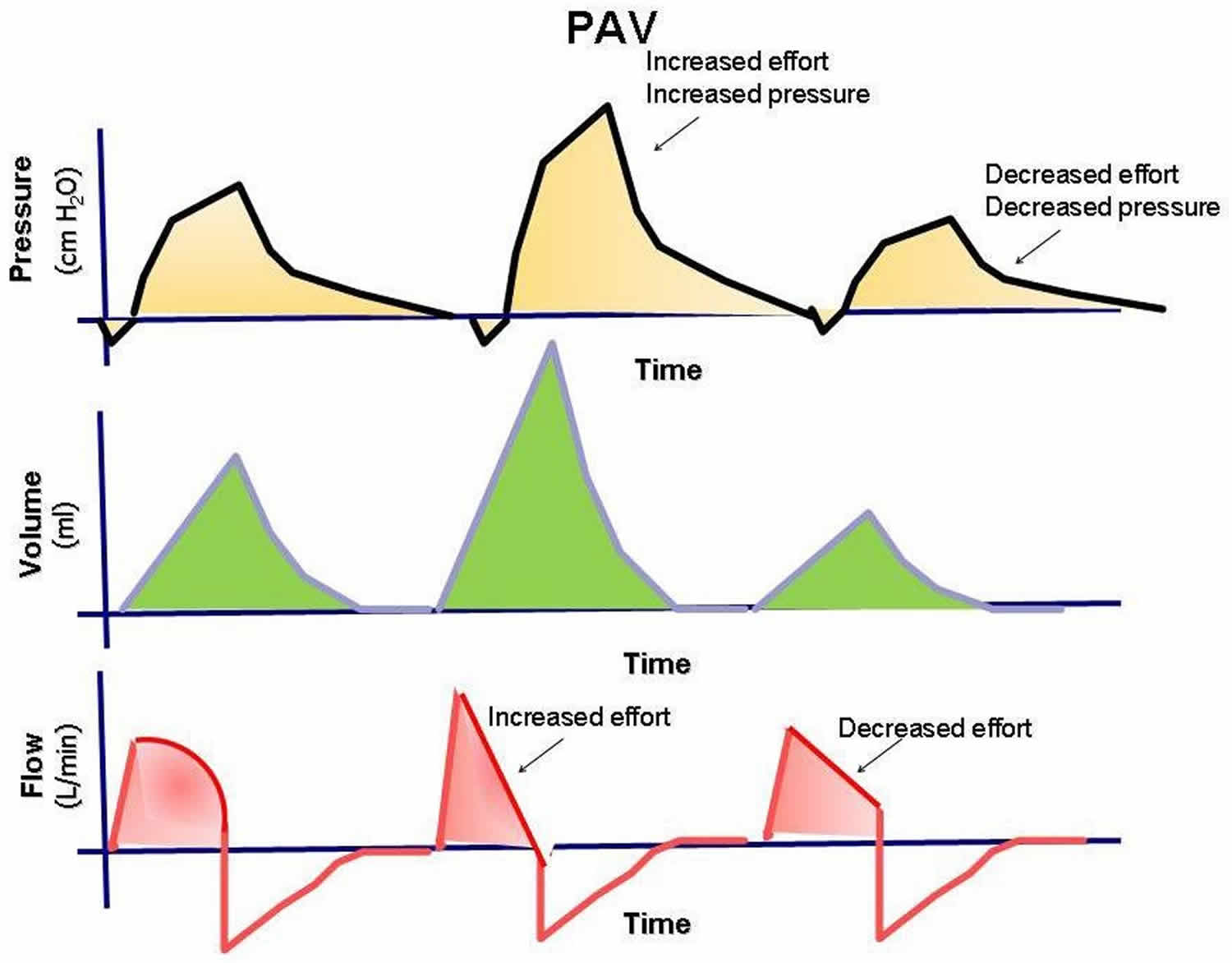

Proportional assist ventilation

Proportional assist ventilation (PAV) mode was designed to decrease the work of breathing and improve patient-ventilator synchrony 2. Proportional assist ventilation (PAV) mode adjusts airway pressure in proportion to the patient’s effort. Unlike other modes in which the physician presets a specific tidal volume or pressure, proportional assist ventilation (PAV) lets the patient determine the inspired volume and the flow rate. This mode requires continuous measurements of resistance and compliance to determine the amount of pressure to give. The support given is a proportion of the patient’s effort and is normally set at 80%. This support is always changing according to patient’s effort and lung dynamics. If the patient’s effort and/or demand are increased, the ventilator support is increased, and vice versa, to always give a set proportion of the breath. The patient’s work of breathing remains constant regardless of his or her changing effort or demand. Proportional assist ventilation (PAV) mode can be used only in patients with spontaneous respiratory efforts. Proportional assist ventilation (PAV) mode has promise, but the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved it for commercial use.

Figure 4. Proportional assist ventilation mode (PAV)

Airway pressure–release ventilation

Bilevel, or biphasic, ventilation is a relatively new mode of ventilation that has recently gained popularity. The ventilator is set at 2 pressures (high CPAP, low CPAP), and both levels are time cycled. The high pressure is maintained for most of the time, while the low pressure is maintained for short intervals of usually less than 1 second to allow exhalation and gas exchange to occur. The patient can breathe spontaneously during high or low pressure. Airway pressure–release ventilation mode has the benefit of alveolar recruitment. Its disadvantage is that the tidal volume is variable. The clinician must be constantly aware of the patient’s minute ventilation to prevent severe hypercapnia or hypocapnia.

Figure 5. Airway pressure–release ventilation mode (APRV)

Tidal volume and rate

For a patient without preexisting lung disease, the tidal volume and rate are traditionally selected by using the 12-12 rule. A tidal volume of 12 mL for each kilogram of lean body weight is programmed to be delivered 12 times a minute in the assist-control mode.

For patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the tidal volume and rate are slightly reduced to the 10-10 rule to prevent overinflation, hyperventilation, and auto–positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). A tidal volume of 10 mL/kg lean body weight is delivered 10 times a minute in the assist-control mode.

In acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the lungs may function best and volutrauma (see Complications of Mechanical Ventilation) is minimized with low tidal volumes of 6-8 mL/kg. Tidal volumes are preset at 6-8 mL/kg of lean body weight in the assist-control mode. This ventilatory strategy is called lung-protective ventilation. These lowered volumes may lead to slight hypercarbia. An elevated PCO2 is typically recognized and accepted without correction, leading to the term permissive hypercapnia. However, the degree of respiratory acidosis allowable is a pH not less than 7.25. The respiratory rate of the ventilator may need to be adjusted upward to increase the minute ventilation lost by using smaller tidal volumes.

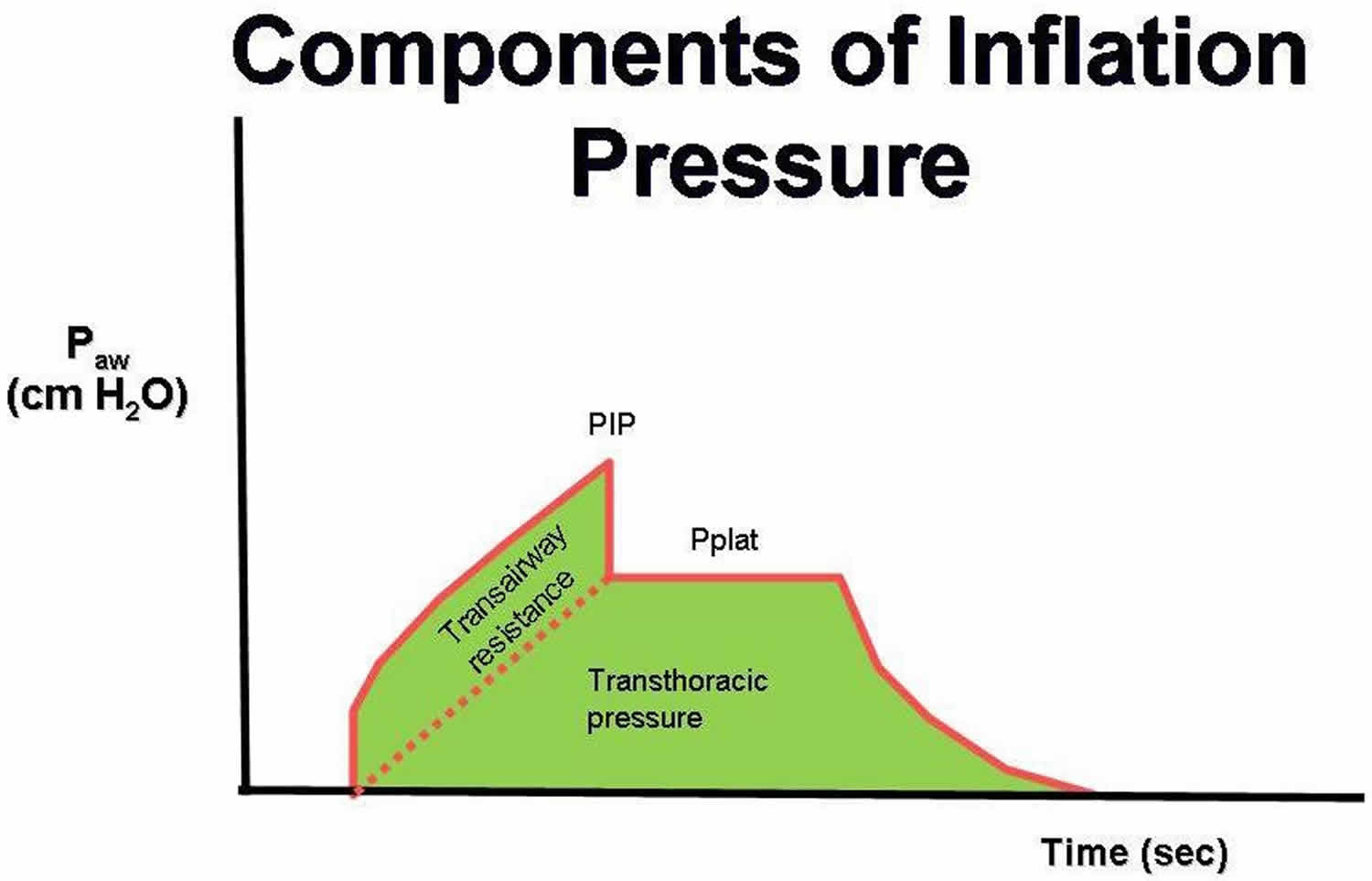

Double-checking the selected tidal volume

After a tidal volume is selected, the peak airway pressure necessary to deliver a single breath should be determined. As the tidal volume increases, so does the pressure required to force that volume into the lung. Persistent breath-to-breath peak pressures greater than 45 cm water are a risk factor for barotrauma. The tidal volume suggested by the above rules may need to be decreased in some patients to keep the peak airway pressure less than 45 cm water.

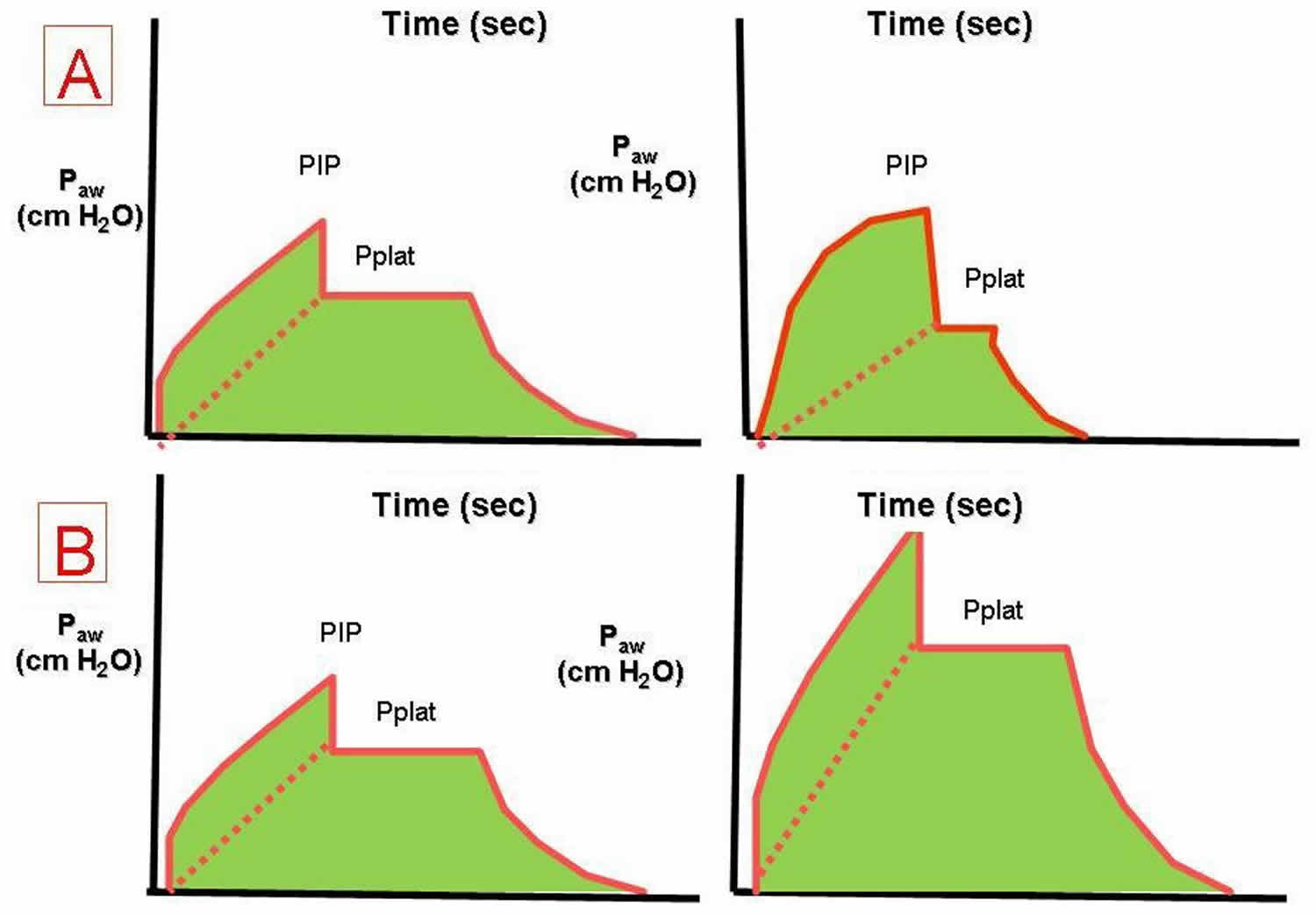

Figure 6. Components of mechanical ventilation inflation pressures

Abbreviations: Paw = airway pressure; PIP = peak airway pressure; Pplat = plateau pressure

Some researchers have suggested that plateau pressures should be monitored as a means to prevent barotrauma in the patient with ARDS. Plateau pressures are measured at the end of the inspiratory phase of a ventilator-cycled tidal volume. The ventilator is programmed not to allow expiratory airflow at the end of the inspiration for a set time, typically half a second. The pressure measured to maintain this lack of expiratory airflow is the plateau pressure. Barotrauma is minimized when the plateau pressure is maintained at less than 30 cm water (Figure 7). Monitoring the peak and plateau pressures allows physicians to make clinical judgments on the progress of their patient.

Figure 7. Plateau pressure mechanical ventilation

Footnote: The effects of decreased respiratory system compliance (A) and increased airway resistance (B) on the pressure-time waveform.

Abbreviations: Paw = airway pressure; PIP = peak airway pressure; Pplat = plateau pressure

Sighs

Because a spontaneously breathing individual typically sighs 6-8 times each hour to prevent microatelectasis, some investigators once recommended that periodic machine breaths that were 1.5-2 times the preset tidal volume be given 6-8 times per hour. However, the peak pressure often needed to deliver such a volume was high enough to predispose the patient to barotrauma. At present, accounting for sighs is not recommended if the patient is receiving tidal volumes of 10-12 mL/kg or if the patient requires PEEP. When a low tidal volume is used, sighs are preset at 1.5-2 times the tidal volume and delivered 6-8 times an hour if the peak and plateau pressures are within acceptable limits.

Initial fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2)

The highest priority at the start of mechanical ventilation is providing effective oxygenation. For the patient’s safety after intubation, the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) should always be set at 100% until adequate arterial oxygenation is documented. A short period with an FIO2 of 100% is not dangerous to the patient receiving mechanical ventilation and offers the clinician several advantages. First, an FIO2 of 100% protects the patient against hypoxemia if unrecognized problems occur as a result of the intubation procedure. Second, using the PaO2 measured with an FIO2 of 100%, the clinician can easily calculate the next desired FIO2 and quickly estimate the shunt fraction. Nevertheless, FiO2 should be quickly titrated down to the minimal level required to maintain adequate oxygenation to avoid barotrauma.

The degree of shunt with 100% FIO2 can be estimated by applying this general rule: The measured PaO2 is subtracted from 700 mm Hg. For each difference of 100 mm Hg, the shunt is 5%. A shunt of 25% should prompt the clinician to consider the use of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP).

Inadequate oxygenation despite the administration of 100% oxygen should lead to a search for complications of endotracheal intubation (eg, right mainstem intubation) or positive-pressure breathing (pneumothorax). If such complications are not present, PEEP is needed to treat the intrapulmonary shunt pathology. Because only a few disease processes can create an intrapulmonary shunt, a clinically significant estimated shunt should narrow the potential source of hypoxemia to the following conditions:

- Alveolar collapse – Major atelectasis

- Alveolar filling with something other than gas – Lobar pneumonia

- Water and protein – ARDS

- Water – Congestive heart failure

- Blood – Hemorrhage

Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is a mode of therapy used in conjunction with mechanical ventilation. At the end of mechanical or spontaneous exhalation, PEEP maintains the patient’s airway pressure above the atmospheric level by exerting pressure that opposes passive emptying of the lung. This pressure is typically achieved by maintaining a positive pressure flow at the end of exhalation. This pressure is measured in centimeters of water.

PEEP therapy can be effective when used in patients with a diffuse lung disease that results in an acute decrease in functional residual capacity (FRC), which is the volume of gas that remains in the lung at the end of a normal expiration. Functional residual capacity (FRC) is determined by primarily the elastic characteristics of the lung and chest wall. In many pulmonary diseases, functional residual capacity (FRC) is reduced because of the collapse of the unstable alveoli. This reduction in lung volume decreases the surface area available for gas exchange and results in intrapulmonary shunting (unoxygenated blood returning to the left side of the heart). If functional residual capacity (FRC) is not restored, a high concentration of inspired oxygen may be required to maintain the arterial oxygen content of the blood in an acceptable range.

Applying PEEP increases alveolar pressure and alveolar volume. The increased lung volume increases the surface area by reopening and stabilizing collapsed or unstable alveoli. This splinting, or propping open, of the alveoli with positive pressure improves the ventilation-perfusion match, reducing the shunt effect.

After a true shunt is modified to a ventilation-perfusion mismatch with PEEP, lowered concentrations of oxygen can be used to maintain an adequate PaO2. PEEP therapy may also be effective in improving lung compliance. When FRC and lung compliance are decreased, additional energy and volume are required to inflate the lung. By applying PEEP, the lung volume at the end of exhalation is increased. The already partially inflated lung requires less volume and energy than before for full inflation.

When used to treat patients with a diffuse lung disease, PEEP should improve compliance, decrease dead space, and decrease the intrapulmonary shunt effect. The most important benefit of the use of PEEP is that it enables the patient to maintain an adequate PaO2 at a low and safe concentration of oxygen (< 60%), reducing the risk of oxygen toxicity (see Complications of Mechanical Ventilation).

Because PEEP is not a benign mode of therapy and because it can lead to serious hemodynamic consequences, the ventilator operator should have a definite indication to use it. The addition of external PEEP is typically justified when a PaO2 of 60 mm Hg cannot be achieved with an FIO2 of 60% or if the estimated initial shunt fraction is greater than 25%. No evidence supports adding external PEEP during initial setup of the ventilator to satisfy misguided attempts to supply prophylactic PEEP or physiologic PEEP.

Many clinicians use the least-PEEP philosophy, which recommends using the lowest positive pressure that provides an adequate PaO2 with a safe FIO2. Another manner of selecting the optimal PEEP is based on identifying the low inflection point on the volume-pressure curve generated breath to breath by using modern mechanical ventilators. PEEP should be set 1-2 cm of water pressure above this measured low inflection point to obtain the optimal PEEP.

Because trials comparing higher versus lower levels of PEEP in adults with acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) have been underpowered to detect small but potentially important effects on mortality or to explore subgroup differences, Briel et al performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from 2299 patients in 3 trials. Treatment with higher versus lower levels of PEEP was not associated with improved hospital survival: 374 hospital deaths occurred in 1136 patients (32.9%) assigned to treatment with higher PEEP, and 409 hospital deaths occurred in 1163 patients (35.2%) assigned to lower PEEP (adjusted relative risk 0.94) 3. However, in the subgroup of patients with ARDS, higher levels were associated with improved survival: 324 hospital deaths (34.1%) occurred in the higher PEEP group and 368 (39.1%) occurred in the lower PEEP group (adjusted relative risk 0.90) 3.

Because PEEP basically resets the baseline of the pressure-volume curve, the peak and plateau pressures will be affected. The clinician should pay close attention to the status of these pressure measurements.

PEEP adjustment

A PEEP level of less than 10 cm water rarely causes hemodynamic problems in the absence of intravascular volume depletion. The cardiodepressant effects of PEEP are often minimized with judicious intravascular volume support or cardiac inotropic support. Although peak pressure is related to the development of barotrauma, arterial hypotension is related to the mean airway pressure that may decrease venous return to the heart or decrease right ventricular function.

A PEEP level greater than 10 cm water is generally an accepted indication to monitor cardiac output by using a Swan-Ganz catheter. However, if the patient remains clinically stable with an adequate urine output, then hemodynamic monitoring may not be necessary. When PEEP greater than 10 cm water is necessary, the left atrial filling pressure can be estimated after an adjustment is made for the effect of the PEEP on the transducer of the catheter. The equation commonly used is LAP = PCWP – (PEEP/3), where LAP is left atrial pressure and PCWP is pulmonary capillary wedge pressure.

Withdrawal of PEEP from a patient should not be attempted in most clinical situations until the patient has achieved satisfactory oxygenation with an FIO2 of 40% or less. Formal weaning from PEEP is then undertaken by reducing the PEEP in 3- to 5-cm of water decrements while the hemoglobin-oxygen saturations are monitored. An unacceptable decrease in the hemoglobin-oxygen saturation should prompt the clinician to immediately reinstitute the last PEEP level that provided good hemoglobin-oxygen saturation.

Prone positioning

Prone positioning has been used in patients with ARDS and severe hypoxia and improves FRC, postural drainage of secretions, and ventilation-perfusion matching. Moving the intubated patient from the supine position to the prone position requires a coordinated effort from the nursing staff, respiratory therapists, and physicians to prevent inadvertent extubation or loss of various lines and tubes. Prone positioning may improve oxygenation in greater than 50% of such patients, but no survival benefit has been documented.

Sedation, protocols, and prophylaxis

Most patients receiving mechanical ventilation need sedation given by means of continuous infusion or scheduled dosing to help with anxiety and psychological stress inherent with this intervention. Daily interruption of sedation, when clinically allowable, decreases the number of days of mechanical ventilation. This sedation holiday helps the patient become reoriented and prevents the unintended prolonged effects of sedation. Such interruptions also help in assessing the patient for the appropriateness of weaning and hasten the transition to spontaneous respiration. Additionally, it is important to avoid oversedation as it decreases ventilator-free days and increases ICU length of stay.

Studies have demonstrated that protocols driven by respiratory therapy safely decrease the number of ventilator days. These protocols allow the respiratory therapists to begin spontaneous breathing trials when they consider the patient a candidate for weaning.

Elevating the head of the patient’s bed by greater than 30° decreases the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Likewise, rates of ventilator-associated pneumonia can be decreased with implementation of gastrointestinal prophylaxis with histamine-2 blocking agents or proton-pump inhibitors, as well as deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. Each of these measures should be undertaken in all patients receiving mechanical ventilation unless a contraindication is present.

Weaning from mechanical ventilation

Mechanical ventilation can be life saving, but its use also has risks. Mechanical ventilation also doesn’t fix the problem that led to the person needing the ventilator in the first place; it just helps support a person until other treatments become effective, or the person gets better on their own. The health care team always tries to help a person get off the ventilator at the earliest possible time. “Weaning” refers to the process of getting the patient off the ventilator. Some patients may be on a ventilator for only a few hours or days, while others may require the ventilator for longer. How long you may need to be on a ventilator depends on many factors. These can include your overall strength, how well your lungs were before going on the ventilator, and how many other organs are affected (like your brain, heart and kidneys). Some people never improve enough to be taken off the mechanical ventilation completely or at all.

When to withdraw mechanical ventilation

Weaning or, as some physicians prefer, “liberation from mechanical ventilation,” is an important issue. Unnecessary delays in the withdrawal of mechanical ventilatory support increase the patient’s risks for complications and increase the length of ICU stay and hospital costs. However, premature withdrawal from the ventilator can also be deleterious.

Weaning should be considered when the event that precipitated the patient’s need for mechanical support is adequately addressed. Patients should be evaluated each day to determine if they are a candidate for weaning. Patients who may be able to support their own ventilation and oxygenation can often be recognized by assessing objective measurements or by asking the following questions:

- Is the process responsible for the patient’s respiratory failure resolving or improving?

- Is the patient hemodynamically stable? Is the patient free of active cardiac ischemia or unstable arrhythmias, and vasopressor support absent or minimal?

- Is oxygenation adequate with a PaO2 of greater than 60 mm Hg with an FiO2 of less than 40% and a PEEP of less than 5 cm water?

- Are mental and neuromuscular statuses appropriate with the patient on minimal or no sedation? Does the patient have adequate strength of the respiratory muscles?

- Are the acid-base status and electrolyte status optimized?

- Is the patient afebrile?

- Are the patient’s adrenal and thyroid functions adequate to allow for weaning?

Numerous weaning parameters can be used to help predict successful extubation. However, no weaning protocol is 100% accurate in predicting successful weaning and extubation. These weaning parameters must be tailored for each clinical scenario.

For instance, if the rapid, shallow breathing index (the respiratory rate/tidal volume, or frequency/tidal volume [f/Vt]) is less than 105, the patient is likely to be weaned from mechanical ventilation. The investigators who derived this number examined primarily middle-aged patients. However, data from follow-up studies of patients older than 70 years suggest that a slightly higher rapid, shallow breathing index of less than 130 may be acceptable.

These parameters give no insight into whether a patient can protect his or her airway or clear secretions. Clinical judgment and experience play a large role in the physician’s decision to withdraw mechanical ventilatory support. If a patient cannot be extubated and/or if the results of the rapid, swallow breathing test are not satisfactory, the reason for the failure must be evaluated and treated.

Parameters commonly used to assess a patient’s readiness to be weaned from mechanical ventilatory support include the following:

- Respiratory rate less than 25 breaths per minute

- Tidal volume greater than 5 mL/kg

- Vital capacity greater than 10 mL/k

- Minute ventilation less than 10 L/min

- PaO2/FIO2 greater than 200

- Shunt (Qs/Qt) less than 20%

- Negative inspiratory force (NIF) less than (more negative) -25 cm water

- f/Vt less than 105, or less than 130 in elderly patients

Additionally, it has been reported that intercostal retraction after adding dead space may help in the detection of susceptibility to extubation failure 4.

How to withdraw mechanical ventilation

Weaning from mechanical ventilation is intended to shift the work of breathing from the ventilator back to the patient over time. An issue separate from discontinuing ventilator support is determining if the patient can maintain his or her airway and be extubated safely. The weaning process must ensure the patient’s safety while avoiding undue delay that might increase the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.

The 3 general approaches to weaning from mechanical ventilation are:

- Synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV),

- Pressure-support ventilation (PSV), and a

- Spontaneous breathing trial (SBT).

In synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV), breaths are either a mandatory ventilator-controlled breath or a spontaneous breath with or without pressure support. The original intent of synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) was to let the patient’s respiratory muscles rest during the mandatory breaths and to work during the spontaneous breaths (see image below). Weaning is accomplished by decreasing the number of mandatory breaths, gradually increasing the workload of the respiratory muscles. Weaning is typically done by 2 breaths every 1–2 hours. The patient’s heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation indicate his or her ability to accomplish the work of breathing.

Evidence now suggests that the respiratory muscles are not able to rest during the mandatory breaths and that this mode may actually result in muscle fatigue and prolonged mechanical ventilation. Findings from randomized trials suggest that synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) weaning delays extubation compared with pressure-support ventilation (PSV) and spontaneous breathing trial and that it should not be the primary mode of weaning in most patients. However, synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) weaning does ensure that the patient receives some ventilatory support, and it may be favored in institutions where the staffing level of respiratory therapists is not optimal.

In pressure-support ventilation (PSV) weaning, all breaths are spontaneous and combined with enough pressure support to ensure that each breath generates a reasonable tidal volume. Pressure support lowers the work of breathing for the patient. Weaning is performed by gradually decreasing the amount of pressure support and by transferring an increased proportion of the work to the patient. This transfer is continued until the pressure support approaches 5-6 cm water. When the patient can tolerate this level of ventilatory support, extubation is usually successful. Studies have demonstrated that pressure-support ventilation (PSV) weaning reduces the number of days on mechanical ventilation compared with synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) alone. Pressure-support ventilation (PSV) can be used in conjunction with synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) when a patient is weaned from mechanical ventilation (see Figure 8 below). The coupling of these 2 modes is an especially attractive option in frail patients with underlying chronic illnesses.

Figure 8. Synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) and pressure-support (PS) ventilation

Footnote: The pressure, volume, and flow to time waveforms for synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) with pressure-support ventilation.

The preferred method of weaning is the spontaneous breathing trial (SBT). This is an attempt to gauge how the patient might do if he or she is immediately removed from the ventilator. This method is also referred to as the “sink-or-swim” trial. The key is to withdraw ventilatory support while oxygenation is continued.

The simplest form of spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) is the T-piece trial. The patient is disconnected from the ventilator, and the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube is hooked to a flow-by oxygen system, usually from the wall oxygen outlet. The transition from the ventilator tubing to the new tubing attached to the wall oxygen outlet requires extra work and patient monitoring by the respiratory therapist.

The same assessment can be made by using the continuous positive-airway pressure (CPAP) mode while the patient is still connected to the ventilator. This is a relatively common method of assessing the patient’s ability to do the work of breathing by himself or herself. Variations on this theme include adding a small amount of pressure and using a CPAP of 5 cm water or a CPAP of 0 but with a pressure-support ventilation (PSV) of 5-6 cm water to offset the resistance from the artificial airway. To the authors’ knowledge, no controlled studies have shown any superiority in assessing the outcomes of weaning between these approaches.

In some studies, approximately 80% of patients receiving mechanical ventilation do not require prolong weaning. This observation explains why spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) is both useful and practical. This approach has had the most success with weaning in randomized controlled trials. Therefore, it is a preferred approach to removing patients from mechanical ventilation.

The spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) should last 30-90 minutes. At the end of the spontaneous breathing trial (SBT), the patient should be evaluated for possible extubation, as his or her blood pressure, respiratory rate, heart rate, and gas exchange are also considered. A spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) should be performed only once a day. Several spontaneous breathing trial (SBT)s a day offer no additional benefit compared with one.

Complications of mechanical ventilation

Complications that can develop from using mechanical ventilation and are sometimes life threatening can include:

- Infections: The endotracheal tube or trach tube allows germs (bacteria) to get into the lungs more easily. This can cause an infection like pneumonia. Ventilator-associated pneumonia can be a serious problem and may mean a person has to stay on the machine longer. Pneumonia can often be treated with antibiotics.

- Collapsed lung (pneumothorax): Sometimes, a part of the lung that is weak can become too full of air and start to leak. The leak lets air get into the space between the lung and the chest wall. Air in this space takes up room so the lung starts to collapse. If this air leak happens, the air needs to be removed from this space. A different kind of tube (chest tube) can be placed into the chest between the ribs to drain out the extra air. The tube allows the lung to re-expand and seal the leak. The chest tube usually has to stay in for some time to make sure the leak has stopped. Rarely, a sudden collapse of the lung can cause death.

- Lung damage: The pressure of putting air into the lungs with a ventilator can damage the lungs. Doctors try to keep this risk at a minimum by using the lowest amount of pressure that is needed. Very high levels of oxygen may be harmful to the lungs as well. Doctors only give as much oxygen as it takes to make sure the body is getting enough to supply vital organs. Sometimes it is hard to reduce this risk when the lungs are damaged. However, this damage may heal if a person is able to recover from the serious illness.

- Side effects of medications: Sedatives and pain medications can cause a person to seem confused or delirious, and these side effects may continue to affect a person even after the medications are stopped. The healthcare team tries to adjust the right amount of medication for a person. Different people will react to each medicine differently. If an agent to prevent muscle movement is needed, the muscles may be weak for a period of time after the medication is stopped. This may get better over time. Unfortunately, in some cases, the weakness remains for weeks to months.

- Inability to discontinue ventilator support: Sometimes, the condition which led a person to need a ventilator does not improve despite treatment. When this happens, the healthcare team will discuss your treatment preferences regarding continued ventilator support with you, if you are able. Often the healthcare team will have these discussions with your family, as you may be unable to participate due to the severe nature of your illness. In situations where a person is not recovering or is getting worse, a decision may be made to discontinue ventilator support and allow death to occur.

- Complications of intubation: Complications that can occur during placement of an endotracheal tube include upper airway and nasal trauma, tooth avulsion, oral-pharyngeal laceration, laceration or hematoma of the vocal cords, tracheal laceration, perforation, hypoxemia, and intubation of the esophagus. Inadvertent intubation of the right mainstem bronchus is reported in 3-9% of all intubations in adults. Aspiration rates are 8–19% in intubations performed in adults without anesthesia. Sinusitis, tracheal necrosis or stenosis, glottic edema, and ventilator-associated pneumonia may occur with prolonged use of endotracheal tubes.

- Ventilator-induced lung injury: With ventilator-induced lung injury, the alveolar epithelium is at risk for both barotrauma and volutrauma.

- Barotrauma: Barotrauma refers to rupture of the alveolus with subsequent entry of air into the pleural space (pneumothorax) and/or the tracking or air along the vascular bundle to the mediastinum (pneumomediastinum). The true prevalence of barotrauma is difficult to establish, but reports suggest a rate of 10%. Large tidal volumes (> 10 mL/kg) and elevated peak inspiratory and plateau pressures (Pplat > 35) are the most important risk factors. Studies in patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) demonstrated that the severity of the underlying lung pathology is a better predictor of barotrauma than the observed peak inspiratory pressure. Even so, peak inspiratory pressures of less than 45 mm Hg and plateau pressures of less than 30-35 mm Hg are recommended. The inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio can be adjusted by increasing the inspiratory flow rate, by decreasing the tidal volume, and by decreasing the ventilatory rate. Attention to the inspiratory-to-expiratory ratio is important to prevent barotrauma in patients with obstructive airway disease (eg, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Management of barotrauma includes addressing specific complications (eg, chest tube for pneumothorax), lowering plateau pressure to less than 30 by reducing tidal volume and PEEP, and managing the underlying disorder. Barotrauma may be associated with increased mortality, although it is often not the direct cause of death.

- Volutrauma: Volutrauma refers to the local overdistention of normal alveoli. Volutrauma has gained recognition over the last 2 decades and is the impetus for the lung protection ventilation with lower tidal volumes of 6–8 mL/kg. Computed tomography scans have demonstrated that ARDS has a heterogeneous pattern of lung involvement. Abnormal consolidated lung is dispersed within normal lung tissue. When a mechanical ventilation breath is forced into the patient, the positive pressure tends to follow the path of least resistance to the normal or relatively normal alveoli, potentially causing overdistention. This overdistention sets off an inflammatory cascade that augments or perpetuates the initial lung injury, causing additional damage to previously unaffected alveoli. The increased local inflammation lowers the patient’s potential to recover from ARDS. The inflammatory cascade occurs locally and may augment the systemic inflammatory response as well. Thus, it is possible to develop this atelectrauma without high tidal volumes, indicating the need to have a high index of suspicion for this complication 5. Another aspect of volutrauma associated with positive ventilation is the shear force associated with the opening and closing effects on collapsible alveoli. This has also been linked to worsening the local inflammatory cascade. PEEP prevents the alveoli from totally collapsing at the end of exhalation and may be beneficial in preventing this type of injury. Since volutrauma was recognized, lung-protective ventilation strategy is recommended in all patients with ARDS or acute lung injury 6. Of note, lung-protective ventilation has not been shown to decrease mortality or other outcomes in non-ARDS mechanically ventilated patients.

- Oxygen toxicity: Oxygen toxicity is a function of increased FIO2 and its duration of use. Oxygen toxicity is due to the production of oxygen free radicals, such as superoxide anion, hydroxyl radical, and hydrogen peroxide. Oxygen toxicity can cause a variety of complications ranging from mild tracheobronchitis and absorptive atelectasis to diffuse alveolar damage that is indistinguishable from ARDS. No consensus has been established for the level of FIO2 required to cause oxygen toxicity, but this complication has been reported in patients given a maintenance FIO2 of 50% or greater. The clinician is encouraged to use the lowest FIO2 that accomplishes satisfactory oxygenation. The medical literature suggests that the clinician should attempt to attain an FIO2 of 60% or less within the first 24 hours of mechanical ventilation. If necessary, PEEP should be considered a means to improve oxygenation while a safe FIO2 is maintained. When PEEP is effective and not contraindicated because of hemodynamics or other reasons, the patient can usually be oxygenated while the risks of oxygen toxicity are limited.

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia: Ventilator-associated pneumonia is a life-threatening complication with mortality rates of 33-50%. It is reported to occur in 8-28% of patients given mechanical ventilation. The incidence is 1-4 cases per 1000 ventilator days. The risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia is highest immediately after intubation. Ventilator-associated pneumonia is estimated to occur at a rate of 3% per day for the first 5 days, 2% per day for next 5 days, and 1% per day thereafter. Ventilator-associated pneumonia occurs more frequently in trauma, neurosurgical, or burn units than in respiratory units and medical intensive care units. Ventilator-associated pneumonia is defined as a new infection of the lung parenchyma that develops within 48 hours after intubation. The diagnosis can be challenging. Ventilator-associated pneumonia should be suspected when a new or changing pulmonary infiltrate in seen in conjunction with fever, leukocytosis, and purulent tracheobronchial secretions. However, many diseases can cause this clinical scenario. Examples include aspiration pneumonitis, atelectasis, pulmonary thromboembolism, drug reactions, pulmonary hemorrhage, and radiation-induced pneumonitis. Qualitative and quantitative cultures of protected brush and bronchoalveolar lavage specimens may help with the diagnosis, but the utility of these techniques is still debated. Microorganisms implicated in ventilator-associated pneumonia that occurs in the first 48 hours after intubation are flora of the upper airway, including Haemophilus influenza and Streptococcus pneumonia. After this early period, gram-negative bacilli such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Escherichia coli; and Acinetobacter, Proteus, and Klebsiella species predominate. Staphylococcus aureus, especially methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), typically becomes a major infective agent after 7 days of intubation and mechanical ventilation. Most of the medical literature recommends initial therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics that cover pathogens resistant to multiple drugs until the sensitivities of the causative organism are identified. Knowledge of organisms that cause ventilator-associated pneumonia in the individual ICU and the pattern of antibiotic resistance is imperative. Choices of antibiotics should be tailored to the microorganisms and the antimicrobial resistance observed in each ICU. It is important to use an infection-prevention bundle to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. One such bundle can be remembered by the mnemonic I COUGH. I is for incentive spirometry; C is for cough and deep breathing; O is oral care; U is for understanding; G is for getting out of bed; H is for head of bed elevated 7.

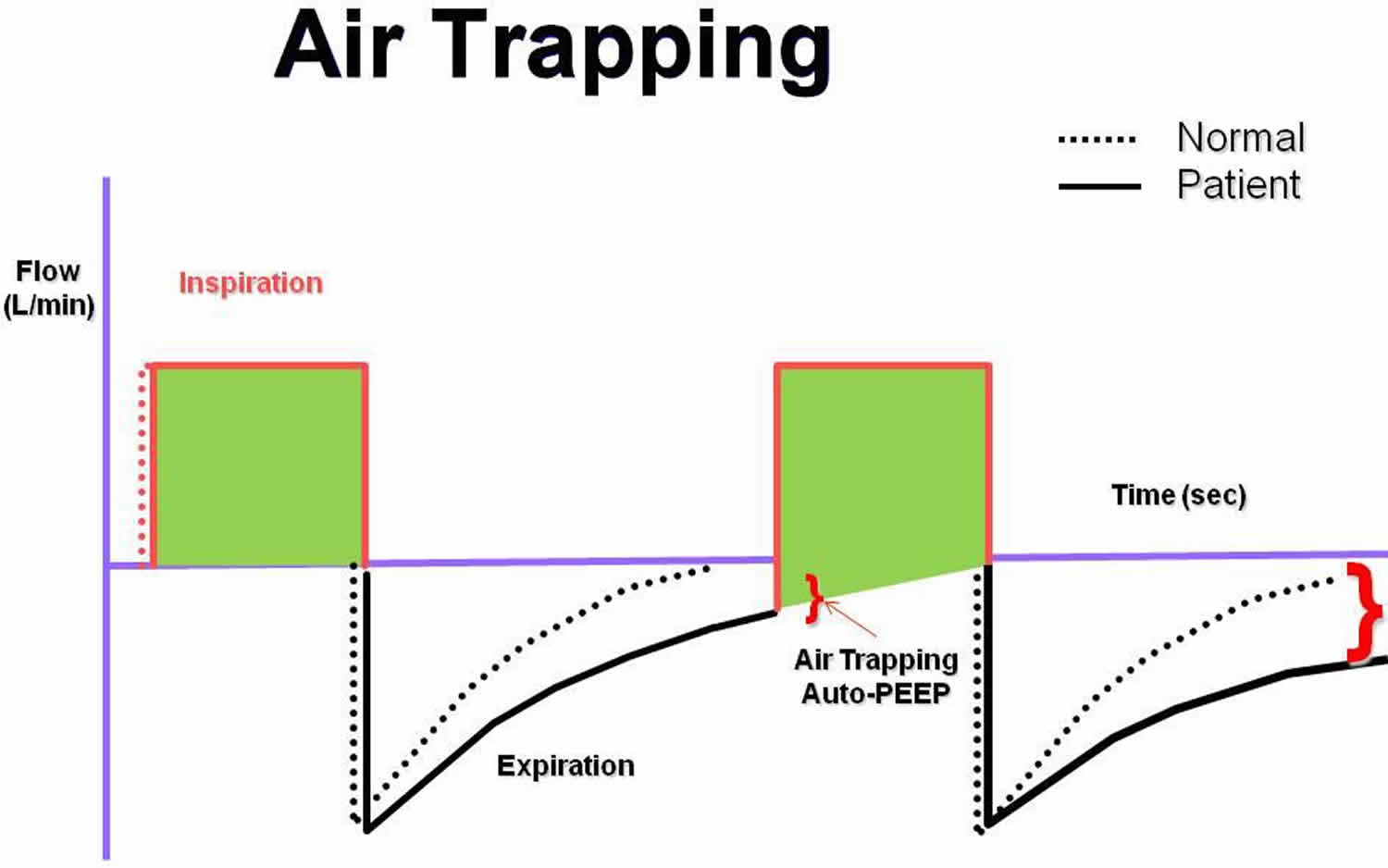

- Intrinsic PEEP, or auto-PEEP: Intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) or auto-PEEP is a complication of mechanical ventilation that most frequently occurs in patients with COPD or asthma who require prolonged expiratory phase of respiration 8. These patients may have difficulty in totally exhaling the ventilator-delivered tidal volume before the next machine breath is delivered. When this problem occurs, a portion of each subsequent tidal volume may be retained in the patient’s lungs, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as breath stacking (see Figure 9 below). If this goes unrecognized, the patient’s peak airway pressure may increase to a level that results in barotrauma, volutrauma, hypotension, patient-ventilator dyssynchrony, or death. Manometry performed by using an esophageal balloon to record changes in pleural pressure is the most accurate way to recognize intrinsic PEEP. However, this technology is not available at most institutions. Therefore, clinicians must anticipate this complication and carefully monitor the measured peak airway pressure. When intrinsic PEEP is diagnosed, the patient should temporarily be released from mechanical ventilation to allow for full expiration. The ventilator can then be adjusted to shorten inspiration by decreasing the set tidal volume, increasing the inspiratory flow rate, or reducing the frequency of respirations. These maneuvers, if performed properly, can increase the expiratory time. The normal inspiratory to expiratory ratio (I:E ratio) is 1:2. In patients with obstructive airway disease, the target I:E ratio should be 1:3 to 1:4.

- Cardiovascular effects: Mechanical ventilation always has some effect on the cardiovascular system. Positive-pressure ventilation can decrease preload, stroke volume, and cardiac output. Positive-pressure ventilation also affects renal blood flow and function, resulting in gradual fluid retention. The incidence of stress ulcers and sedation-related ileus is increased when patients receive mechanical ventilation. In fact, mechanical ventilation is a primary indication for gastrointestinal prophylaxis. Positive pressure maintained in the chest may decrease venous return from the head, increasing intracranial pressure and worsening agitation, delirium, and sleep deprivation.

Figure 9. Air trapping

Footnote: The flow to time waveform demonstrating auto–positive end-expiratory pressure (auto-PEEP).

References- Wozniak DR, Lasserson TJ, Smith I. Educational, supportive and behavioural interventions to improve usage of continuous positive airway pressure machines in adults with obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jan 8. 1:CD007736

- Ambrosino N, Rossi A. Proportional assist ventilation (PAV): a significant advance or a futile struggle between logic and practice?. Thorax. 2002 Mar. 57(3):272-6.

- Briel M, Meade M, Mercat A, et al. Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010 Mar 3. 303(9):865-73.

- Solsona JF, Diaz Y, Vazquez A, Gracia MP, Zapatero A, Marrugat J. A pilot study of a new test to predict extubation failure. Crit Care. 2009 Apr 14. 13(2):R56

- Muthiah MP, Zaman MK. Mechanical ventilation simplified. South Med J. 2009 Dec. 102 (12):1196-7.

- Amato MB, Barbas CS, Medeiros DM, Magaldi RB, Schettino GP, Lorenzi-Filho G, et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998 Feb 5. 338(6):347-54.

- Cassidy MR, Rosenkranz P, McCabe K, Rosen JE, McAneny D. I COUGH: reducing postoperative pulmonary complications with a multidisciplinary patient care program. JAMA Surg. 2013 Aug. 148 (8):740-5.

- Rossi A, Polese G, Brandi G, Conti G. Intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEPi). Intensive Care Med. 1995 Jun. 21(6):522-36.