What is metastatic melanoma

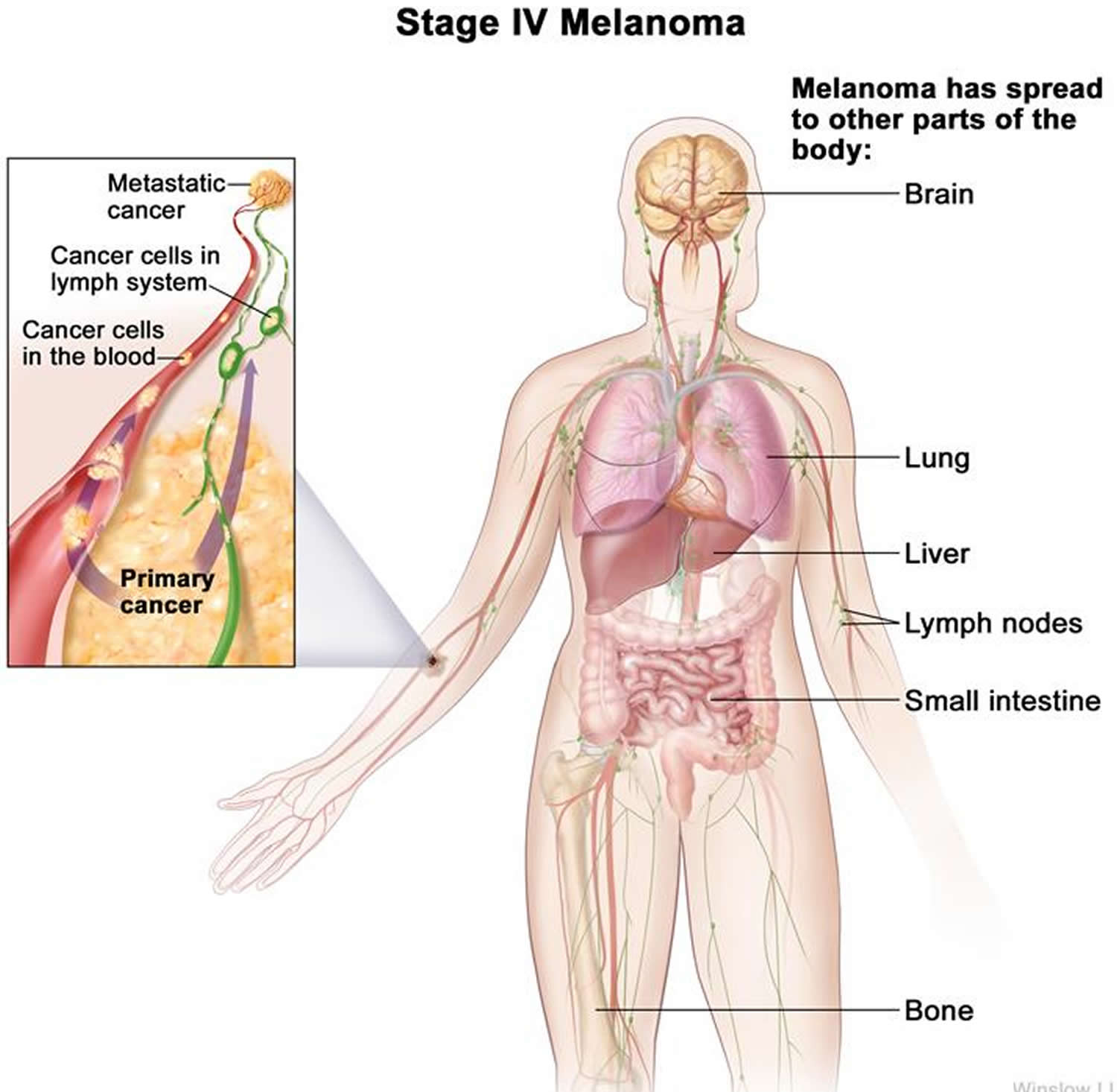

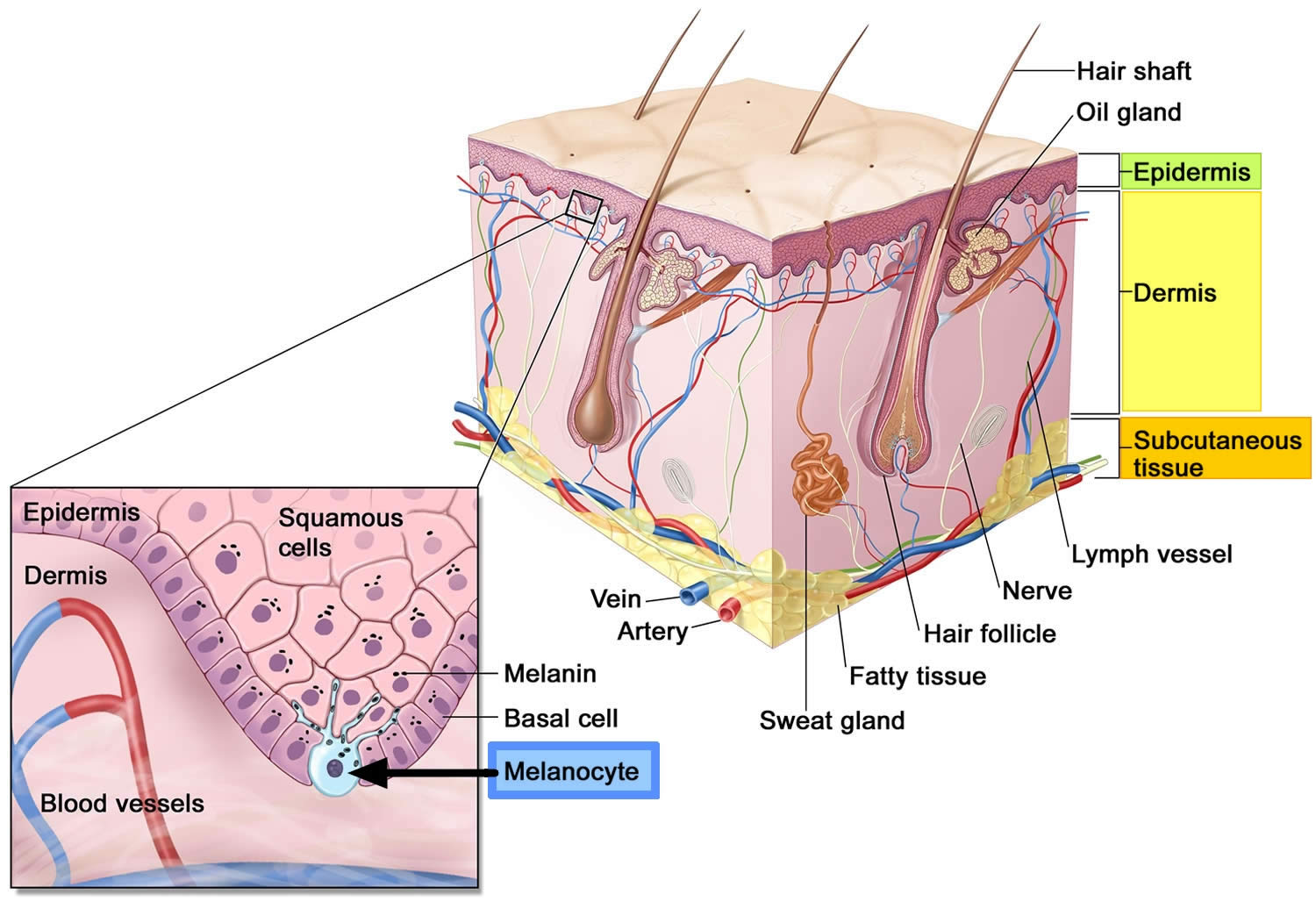

Melanoma is a cancer that begins in the melanocytes (a type of skin cells that produce melanin and melanin gives your skin its color). Metastatic melanoma is considered to be a late form of stage IV (stage 4) of melanoma cancer also known as advanced melanoma and occurs when cancerous melanoma cells in the epidermis metastasize (spread) and progress to other organs of the body that are located far from the original site to internal organs, most often the lung, followed in descending order of frequency by the liver, brain, bone and gastrointestinal tract 1. The two main factors in determining how advanced the melanoma is into Stage IV (the “M” category, for “metastases”) are the site of the distant metastases (nonvisceral, lung or any other visceral metastatic sites) and whether or not the serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level is elevated. LDH (lactate dehydrogenase), an enzyme found in your blood and almost every other cell of your body, turns sugar into energy, and the more you have in your blood or other body fluid, the more damage has been done to your body’s tissues.

It is crucial to diagnose melanoma in its early stages before it metastasizes, as once it has spread, it is difficult to locate its origin and so treatment and patient’s survival rate tends to be hindered 2.

An estimated 178,560 cases of melanoma will be diagnosed in the U.S. in 2018 3. Of those, 87,290 cases will be in situ (noninvasive), confined to the epidermis (the top layer of skin), and 91,270 cases will be invasive, penetrating the epidermis into the skin’s second layer (the dermis) 3.

The most common cause of melanoma is attributed to ultraviolet radiation (UV) exposure, family history, and personal history of melanoma 4. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the incidence of skin cancer is on the rise due to the excessive UV rays that individuals are being exposed to. Additionally, lighter skinned people who have lack of skin pigmentation have a much higher risk of getting nonmelanoma or melanoma skin cancers than compared to dark-skinned patients, due to their increased risk of UV-induced sunburn skin damage 5.

Melanomas can develop anywhere on the skin, but they are more likely to start on the trunk (chest and back) in men and on the legs in women. The neck and face are other common sites.

Having darkly pigmented skin lowers your risk of melanoma at these more common sites, but anyone can get melanoma on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, and under the nails. Melanomas in these areas make up a much larger portion of melanomas in African Americans than in whites.

Melanomas can also form in other parts of your body such as the eyes, mouth, genitals, and anal area, but these are much less common than melanoma of the skin.

Melanoma is much less common than basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers. But melanoma is more dangerous because it’s much more likely to spread to other parts of the body if not caught early.

Most melanoma cells still make melanin, so melanoma tumors are usually brown or black. But some melanomas do not make melanin and can appear pink, tan, or even white.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the skin

Footnote: Anatomy of the skin, showing the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Melanocytes are in the layer of basal cells at the deepest part of the epidermis.

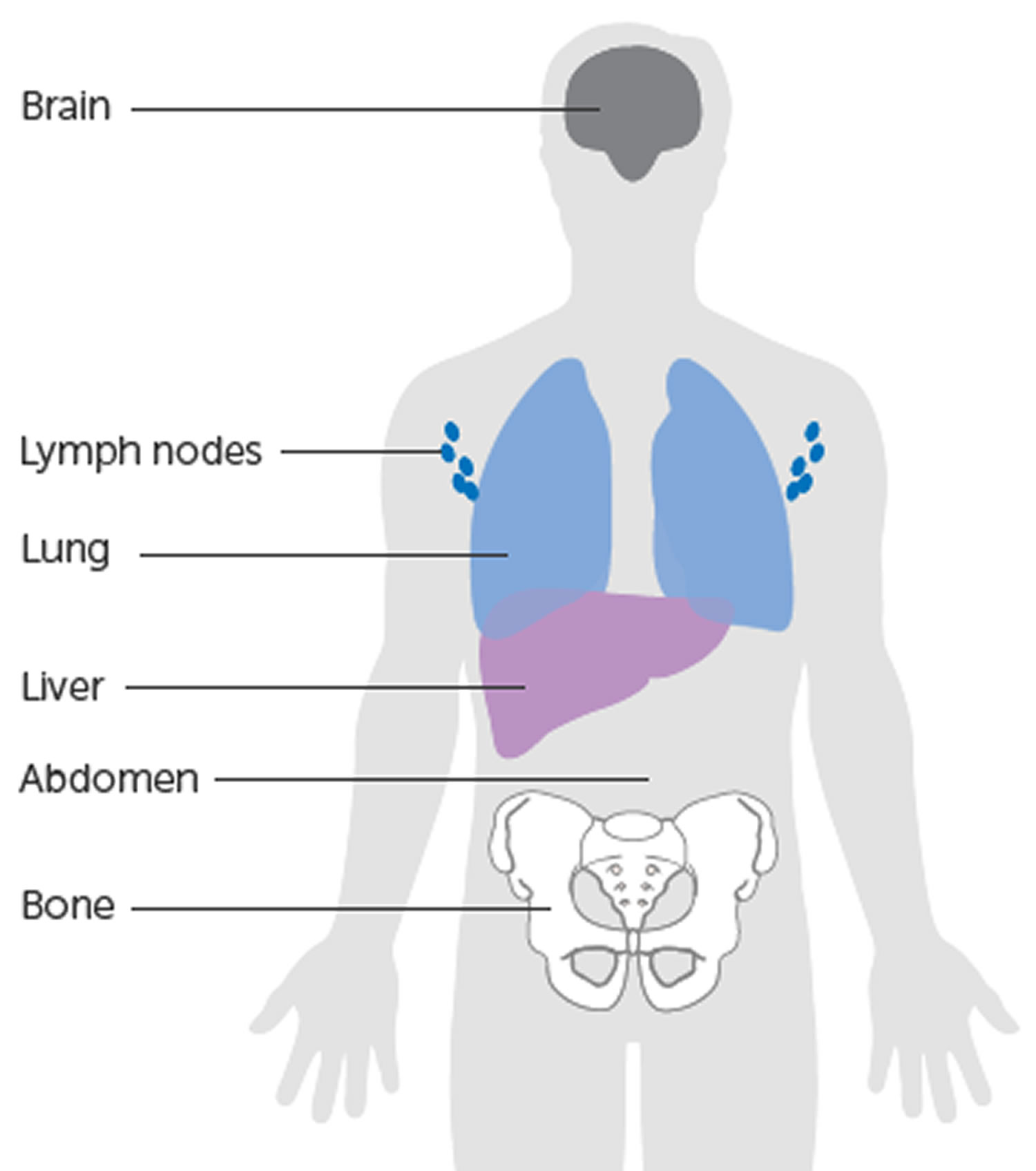

Figure 2. Where metastatic melanoma spread to

[Source 6 ]Figure 3. Metastatic melanoma

Footnote: Figure 2A, Anterior view. Numerous small pigmented lesions distributed widely on the abdomen and chest. B, Posterior view. Numerous small pigmented lesions and, on the left scapula, a larger pigmented lesion that is blackish and irregular.

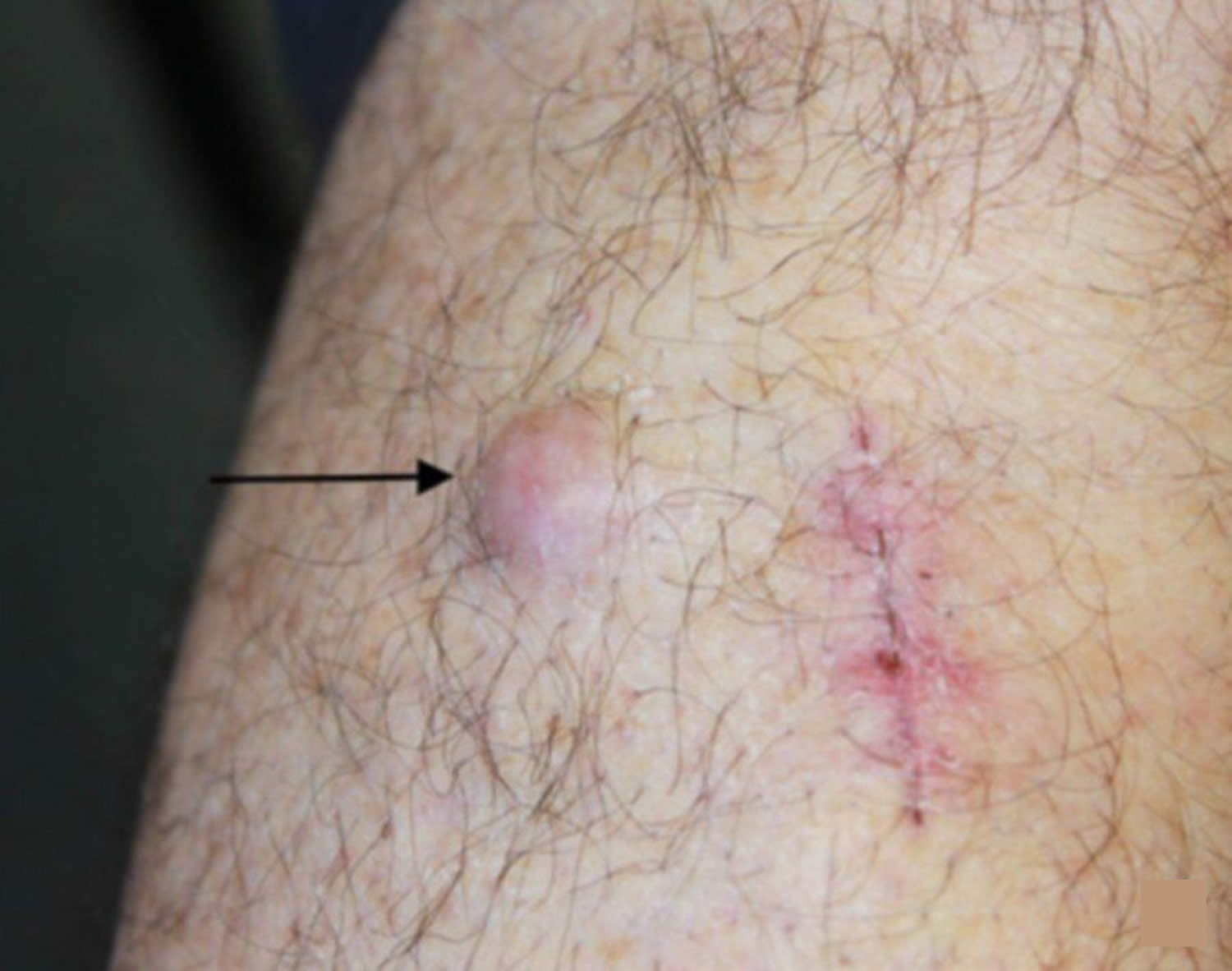

[Source 7 ]Figure 4. Metastatic melanoma local spread

[Source 8 ]Figure 5. Metastatic melanoma distant spread

[Source 8 ]Melanoma metastasis sites

Melanoma can spread to almost anywhere in the body but the most common places for it to spread are the:

- lymph nodes

- lungs

- liver

- bones

- brain

- abdomen

Metastatic melanoma classification

Metastatic melanoma can be classified into local recurrence, in transit metastasis, nodal metastasis, and haematogenous spread.

Local recurrence of melanoma

Local recurrence is defined as a recurrence of melanoma within 2 cm of the surgical scar of primary melanoma. It can result either from direct extension of the primary melanoma or from spread via the lymphatic vessels.

In-transit melanoma metastases

In-transit metastases are melanoma deposits within the lymphatic vessels more than 2 cm from the site of the primary melanoma.

Nodal melanoma metastasis

Nodal metastasis is metastatic melanoma involving the lymph nodes. Every site on the body drains initially to one or two nearby lymph node basins. The lymph nodes first involved are the regional lymph nodes. Usually, the involved lymph nodes become enlarged and may be be felt as a lump through the skin.

Hematogenous spread of melanoma

Hematogenous spread is spread of melanoma cells in the bloodstream, which can happen either by a tumor invading blood vessels or secondary to lymph node involvement. Once in the bloodstream, melanoma cells can travel to distant sites in the body and deposit. It can proliferate in any tissue but most often grows in the lungs, in or under the skin, the liver and brain. Many patients also develop metastases in bone, gastrointestinal tract, heart, pancreas, adrenal glands, kidneys, spleen and thyroid.

Diffuse melanosis cutis

Diffuse melanosis cutis is a rare presentation of metastatic melanoma in which the entire skin surface changes color.

Melanoma-associated leukoderma

Melanoma-associated leukoderma is depigmentation that occurs in patients with metastatic melanoma. It may present as white areas within a melanoma due to regression, halo melanoma, or as white patches resembling vitiligo distant from the melanoma. Leukoderma associated with metastatic melanoma is also known as melanoma-associated vitiligo.

Leukoderma can also be triggered by drugs used to treat metastatic melanoma, such as ipilimumab, immune checkpoint inhibitors (pembrolizumab, nivolumab), and BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib)

Metastatic melanoma staging

If you receive a diagnosis of melanoma, the next step is to determine the extent (stage) of the cancer. This process is called staging. Melanoma staging means finding out if the melanoma has spread from its original site in the skin. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics. Melanoma staging can be very complex, so if you have any questions about the stage of your cancer or what it means, ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

To assign a stage to your melanoma, your doctor will:

- Determine the thickness. The thickness of a melanoma is determined by carefully examining the melanoma under a microscope and measuring it with a special tool. The thickness of a melanoma helps doctors decide on a treatment plan. In general, the thicker the tumor, the more serious the disease. Thinner melanomas may only require surgery to remove the cancer and some normal tissue around it. If the melanoma is thicker, your doctor may recommend additional tests to see if the cancer has spread before determining your treatment options.

- See if the melanoma has spread to the lymph nodes. If there’s a risk that the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, your doctor may recommend a procedure known as a sentinel node biopsy. A sentinel lymph node is defined as the first lymph node to which cancer cells are most likely to spread from a primary tumor. Sometimes, there can be more than one sentinel lymph node. During a sentinel node biopsy, a dye is injected in the area where your melanoma was removed. The dye flows to the nearby lymph nodes. The first lymph nodes to take up the dye are removed and tested for cancer cells. If these first lymph nodes (sentinel lymph nodes) are cancer-free, there’s a good chance that the melanoma has not spread beyond the area where it was first discovered.

- Look for signs of cancer beyond the skin. For people with more-advanced melanomas, doctors may recommend imaging tests to look for signs that the cancer has spread to other areas of the body. Imaging tests may include X-rays, CT scans and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. These imaging tests generally aren’t recommended for smaller melanomas with a lower risk of spreading beyond the skin.

Other factors may go into determining the risk that the cancer may spread (metastasize), including whether the skin over the area has formed an open sore (ulceration) and how many dividing cancer cells (mitoses) are found when looking under a microscope.

Most melanoma specialists refer to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- The extent of the main (primary) tumor (T): How deep has the cancer grown into the skin? Is the cancer ulcerated?

- Tumor thickness: The thickness of the melanoma is called the Breslow thickness. In general, melanomas less than 1 millimeter (mm) thick (about 1/25 of an inch) have a very small chance of spreading. As the melanoma becomes thicker, it has a greater chance of spreading.

- Ulceration: Ulceration is a breakdown of the skin over the melanoma. Melanomas that are ulcerated tend to have a worse outlook.

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs ? (Melanoma can spread almost anywhere in the body, but the most common sites of spread are the lungs, liver, brain, bones, and the skin or lymph nodes in other parts of the body.)

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

The staging system in the table below uses the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage). It is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. Sometimes, if surgery is not possible right away or at all, the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests. The clinical stage will be used to help plan treatment. Sometimes, though, the cancer has spread further than the clinical stage estimates, and may not predict the patient’s outlook as accurately as a pathologic stage.

There are both clinical and pathologic staging systems for melanoma. Since most cancers are staged with the pathologic stage, we have included that staging system below. If your cancer has been clinically staged, it is best to talk to your doctor about your specific stage.

The table below is a simplified version of the TNM system. It is based on the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system, effective January 2018. It’s important to know that melanoma cancer staging can be complex. If you have any questions about the stage of your cancer or what it means, please ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 1. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system for Melanoma

| AJCC Stage | Melanoma Stage Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | This stage is also known as melanoma in situ. The cancer is confined to the epidermis, the outermost skin layer (Tis). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 1 | The tumor is no more than 2 mm (2/25 of an inch) thick and might or might not be ulcerated (T1 or T2a). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant parts of the body (M0) | |

| 2 | The tumor is more than 2 mm thick (T2b or T3) and may be thicker than 4 mm (T4). It might or might not be ulcerated. The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 3A | The tumor is no more than 2 mm thick and might or might not be ulcerated (T1 or T2a). The cancer has spread to 1 to 3 nearby lymph nodes, but it is so small that it is only seen under the microscope (N1a or N2a). It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 3B | There is no sign of the primary tumor (T0) AND: The cancer has spread to only one nearby lymph node (N1b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor (without reaching the nearby lymph nodes) (N1c) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| OR | ||

| The tumor is no more than 4 mm thick and might or might not be ulcerated (T1, T2, or T3a) AND: The cancer has spread to only one nearby lymph node (N1a or N1b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor (without reaching the nearby lymph nodes) (N1c) OR It has spread to 2 or 3 nearby lymph nodes (N2a or N2b) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | ||

| 3C | There is no sign of the primary tumor (T0) AND: The cancer has spread to 2 or more nearby lymph nodes, at least one of which could be seen or felt (N2b or N3b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, and it has reached the nearby lymph nodes (N2c or N3c) OR It has spread to nearby lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3b or N3c) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| OR | ||

| The tumor is no more than 4 mm thick, and might or might not be ulcerated (T1, T2, or T3a) AND: The cancer has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, and it has reached nearby lymph nodes (N2c or N3c) OR The cancer has spread to 4 or more nearby lymph nodes (N3a or N3b), or it has spread to nearby lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3b or N3c) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | ||

| OR | ||

| The tumor is more than 2 mm but no more than 4 mm thick and is ulcerated (T3b) OR it is thicker than 4 mm but is not ulcerated (T4a). The cancer has spread to one or more nearby lymph nodes AND/OR it has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor (N1 or higher). It has not spread to distant parts of the body. | ||

| OR | ||

| The tumor is thicker than 4 mm and is ulcerated (T4b) AND: The cancer has spread to 1 to 3 nearby lymph nodes, which are not clumped together (N1a/b or N2a/b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, and it might (N2c) or might not (N1c) have reached 1 nearby lymph node) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | ||

| 3D | The tumor is thicker than 4 mm and is ulcerated (T4b) AND: The cancer has spread to 4 or more nearby lymph nodes (N3a or N3b) OR It has spread to nearby lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3b) It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, AND it has spread to at least 2 nearby lymph nodes, or to lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3c) OR It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 4 | The tumor can be any thickness and might or might not be ulcerated (any T). The cancer might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (any N). It has spread to distant lymph nodes or to organs such as the lungs, liver or brain (M1). | |

Footnotes: The staging system in the table above uses the pathologic stage also called the surgical stage. This is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. Sometimes, if surgery is not possible right away (or at all), the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of physical exams, biopsies, and imaging tests. The clinical stage will be used to help plan treatment. Sometimes, though, the cancer has spread farther than the clinical stage estimates, so it may not predict a person’s outlook as accurately as a pathologic stage. If your cancer has been clinically staged, it is best to talk to your doctor about your specific stage.

[Source 9 ]Metastatic melanoma life expectancy

The 5-year survival rate for a metastatic melanoma is about 31.9% 10. The 10-year survival is about 10% to 15% 11. The outlook is better if the spread is only to distant parts of the skin or distant lymph nodes rather than to other organs, and if the blood level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is normal.

- The survival differences among M categories will be useful for clinical trial stratification; however, the overall prognosis of all patients with stage IV melanoma remains poor, even among patients with M1a. For this reason, the Melanoma Staging Committee recommended no stage groupings for stage IV.

Table 2. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system (M category) for Stage 4 Melanoma

| M (metastasis) | Site | Serum LDH |

|---|---|---|

| M0 | No distant metastases | NA |

| M1a | Distant skin, subcutaneous, or nodal metastases | Normal |

| M1b | Lung metastases | Normal |

| M1c | All other visceral metastases | Normal |

| Any distant metastasis | Elevated |

Abbreviations: NA = not applicable; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase.

[Source 12]Staging for Distant Metastatic Melanoma (stage 4)

In patients with distant metastases, the site(s) of metastases and elevated serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) are used to delineate the M1 stage into three M categories: M1a, M1b, and M1c. One-year survival rates among 7,972 stage 4 patients were 62% for M1a, 53% for M1b, and 33% for M1c melanomas (see Figure 1A) 12.

Patients with distant metastasis in the skin, subcutaneous tissue, or distant lymph nodes and a normal LDH level are categorized as M1a; they have a relatively better prognosis compared with those patients with metastases located in any other distant anatomic site (see Figure 1A) 12. Patients with metastasis to the lung (or with a combination of lung and skin or subcutaneous metastases) and a normal LDH level are categorized as M1b and have an intermediate prognosis. Those patients with metastases to any other visceral sites or at any location with an elevated LDH level are designated as M1c and have the worst prognosis (see Figure 1A and 1B).

Elevated serum LDH

The updated AJCC Melanoma Staging Database demonstrated that an elevated serum LDH is an independent and highly significant predictor of survival outcome among patients with stage IV disease. Thus 1- and 2-year overall survival rates for those stage IV patients in the 2008 AJCC Melanoma Staging Database with a normal serum LDH were 65% and 40%, respectively, compared with 32% and 18%, respectively, when the serum LDH was elevated at the time of staging (Figure 1B). Therefore, serum LDH should be measured at the time stage IV disease is documented, and if the LDH level is elevated, those patients are assigned to M1c regardless of the site of their distant metastases.

Factors other than stage can also affect survival. For example:

- Older people generally have shorter survival times than younger people, regardless of stage.

- Melanoma is uncommon among African Americans, but when it does occur, survival times tend to be shorter than when it occurs in whites. Some studies have found that melanoma tends to be more serious if it occurs on the sole of the foot or palm of the hand, or if it is in a nail bed. (Cancers in these areas make up a larger portion of melanomas in African Americans than in whites.)

- People with melanoma who have weakened immune systems, such as people who have had organ transplants or who are infected with HIV, also are at greater risk of dying from their melanoma.

Figure 6. Metastatic melanoma life expectancy

Footnote: Survival curves of 7,635 patients with metastatic melanomas at distant sites (stage 4) subgrouped by (A) the site of metastatic disease and (B) serum lactose dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. LDH values are not used to stratify patients. Curves in (A) are based only on site of metastasis. The number of patients is shown in parentheses.

Footnote: Survival curves of 7,635 patients with metastatic melanomas at distant sites (stage 4) subgrouped by (A) the site of metastatic disease and (B) serum lactose dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. LDH values are not used to stratify patients. Curves in (A) are based only on site of metastasis. The number of patients is shown in parentheses.SQ = subcutaneous.

[Source 12]Metastatic melanoma prognosis

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options. According to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program (based on 2012–2018 statistics), those with distant metastatic melanoma have a 5-year survival rate of 31.9% 10.

The prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options depend on the following:

- The thickness of the tumor and where it is in the body.

- How quickly the cancer cells are dividing.

- Whether there was bleeding or ulceration of the tumor.

- How much cancer is in the lymph nodes.

- The number of places cancer has spread to in the body.

- The level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the blood.

- Whether the cancer has certain mutations (changes) in a gene called BRAF.

- The patient’s age and general health.

Metastatic melanoma symptoms

The most important warning sign of melanoma is a new spot on the skin or a spot that is changing in size, shape, or color. Another important sign is a spot that looks different from all of the other spots on your skin (known as the ugly duckling sign). If you have one of these warning signs, have your skin checked by a doctor.

The ABCDE rule is another guide to the usual signs of melanoma. Be on the lookout and tell your doctor about spots that have any of the following features:

- A is for Asymmetry: One half of a mole or birthmark does not match the other.

- B is for Border: The edges are irregular, ragged, notched, or blurred.

- C is for Color: The color is not the same all over and may include different shades of brown or black, or sometimes with patches of pink, red, white, or blue.

- D is for Diameter: The spot is larger than 6 millimeters across (about ¼ inch – the size of a pencil eraser), although melanomas can sometimes be smaller than this.

- E is for Evolving: The mole is changing in size, shape, or color.

Some melanomas don’t fit these rules. It’s important to tell your doctor about any changes or new spots on the skin, or growths that look different from the rest of your moles.

Other warning signs are:

- A sore that doesn’t heal

- Spread of pigment from the border of a spot into surrounding skin

- Redness or a new swelling beyond the border of the mole

- Change in sensation, such as itchiness, tenderness, or pain

- Change in the surface of a mole – scaliness, oozing, bleeding, or the appearance of a lump or bump

Be sure to show your doctor any areas that concern you and ask your doctor to look at areas that may be hard for you to see. It’s sometimes hard to tell the difference between melanoma and an ordinary mole, even for doctors, so it’s important to show your doctor any mole that you are unsure of.

The symptoms of stage 4 metastatic melanoma depend on where the cancer is in the body. They might include:

- hard or swollen lymph nodes

- hard lump on your skin

- unexplained pain

- feeling very tired or unwell

- unexplained weight loss

- yellowing of eyes and skin (jaundice)

- build up of fluid in your abdomen – ascites

- abdominal pain

Symptoms if melanoma has spread to the lymph nodes

Lymph nodes are small round organs that are part of your body’s lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is a part of your immune system. The lymphatic system consists of a network of vessels and organs that contains lymph, a clear fluid that carries infection-fighting white blood cells as well as fluid and waste products from the body’s cells and tissues. In a person with cancer, lymph can also carry cancer cells that have broken off from the main tumor.

Many types of cancer spread through the lymphatic system, and one of the earliest sites of spread for these cancers is nearby lymph nodes.

The most common symptom if melanoma has spread to the lymph nodes is that they feel hard or swollen. Swollen lymph nodes in the neck area can make it hard to swallow.

Cancer cells can also stop lymph fluid from draining away. This might lead to swelling in the neck or face due to fluid buildup in that area. The swelling due to build-up of lymph fluid in soft body tissues when the lymph system is damaged or blocked is called lymphedema.

Symptoms if melanoma has spread to the lungs

You may have any of these symptoms if your melanoma has spread into your lungs:

- a cough that doesn’t go away

- breathlessness

- ongoing chest infections

- coughing up blood

- a buildup of fluid between the chest wall and the lung (a pleural effusion).

Symptoms if melanoma has spread to the liver

You might have any of the following symptoms if your melanoma has spread to your liver:

- discomfort or pain on the right side of your tummy (abdomen)

- feeling sick

- poor appetite and weight loss

- a swollen abdomen called ascites (a condition in which fluid collects in spaces within your abdomen)

- yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice)

- itchy skin

Symptoms if melanoma has spread to your bone

You might have any of the following symptoms if your melanoma has spread to the bones:

- pain from breakdown of the bone – the pain is continuous and people often describe it as gnawing

- backache, which gets worse despite resting

- weaker bones – they can break more easily

- raised blood calcium (hypercalcemia), which can cause dehydration, confusion, sickness, tummy (abdominal) pain and constipation

- low levels of blood cells – blood cells are made in the bone marrow and can be crowded out by the cancer cells, causing anemia, increased risk of infection, bruising and bleeding

Metastatic melanoma in the spinal bones can cause pressure on the spinal cord. If it isn’t treated, it can lead to weakness in your legs, numbness, paralysis and loss of bladder and bowel control (incontinence). This is called spinal cord compression. It is an emergency so if you have these symptoms, you need to contact your cancer specialist straight away or go to the accident and emergency department.

Symptoms if melanoma has spread to the brain

You might have any of the following symptoms if your melanoma has spread to your brain:

- headaches

- nausea and vomiting

- weakness of a part of the body

- fits (seizures)

- personality changes or mood changes

- eyesight changes or visual disturbances

- ataxia (impaired balance or coordination)

- confusion

- mental status alterations

- difficulty speaking

However, 10% of patients may be asymptomatic.

Figure 7. Metastatic melanoma in the brain (MRI scan)

Metastatic melanoma treatment

Stage 4 metastatic melanomas are often hard to cure, as they have already spread to distant lymph nodes or other areas of the body. Skin tumors or enlarged lymph nodes causing symptoms can often be removed by surgery or treated with radiation therapy.

In some cases, a deposit of metastatic melanoma can be surgically removed. This is an appropriate treatment option with the aim of cure when there is a solitary metastasis of the skin, in the subcutaneous tissue or of a lymph node. Sometimes surgery is done when there is felt to be one metastasis to another organ such as the liver. Metastases in internal organs are sometimes removed, depending on how many there are, where they are, and how likely they are to cause symptoms. Surgery may also be helpful in reducing symptoms and improving quality of life, even if it will not be expected to cure the disease.

Metastases that cause symptoms but cannot be removed may be treated with radiation, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, or chemotherapy.

The treatment of metastatic melanomas has changed in recent years as newer forms of immunotherapy and targeted drugs have been shown to be more effective than chemotherapy 13.

Immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda), nivolumab (Opdivo), nivolumab combined with relatlimab (Opdualag) or nivolumab or pembrolizumab plus ipilimumab (Yervoy) have been shown to help some people with advanced melanoma live longer. Combinations of checkpoint inhibitors might be more effective, although they’re also more likely to result in serious side effects. People who get any of these drugs need to be watched closely for serious side effects. Other types of immunotherapy might also help, but these are only available through clinical trials (https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials).

In about half of all melanomas, the melanoma cancer cells have changes in the BRAF gene. If you have changes in the BRAF gene, doctors describe your melanoma as BRAF positive. (If you don’t have changes, then your melanoma is BRAF negative.) The BRAF gene makes the melanoma cells produce too much BRAF protein, which can make melanoma cells grow. If a BRAF gene change is found, treatment with newer targeted therapy drugs – typically a combination of a BRAF inhibitor and a MEK inhibitor – might be a good option. Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab or nivolumab might be another option, as well as a combination of targeted drugs plus the immune checkpoint inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq). Like the checkpoint inhibitors, these drugs can help some people live longer, although they haven’t been shown to cure these melanomas.

A small portion of melanomas have changes in the C-KIT gene. These melanomas might be helped by targeted drugs such as imatinib (Gleevec) and nilotinib (Tasigna), although, again, these drugs aren’t known to cure these melanomas.

Immunotherapy using interferon or interleukin-2 can help a small number of people with stage IV melanoma live longer. Higher doses of these drugs seem to be more effective, but they can also have more severe side effects, so they might need to be given in the hospital.

Chemotherapy can help some people with stage IV melanoma by slowing the rate of progression of metastatic melanoma but it does not cure it, however, other treatments are usually tried first. Dacarbazine (DTIC) and temozolomide (Temodar) are the chemo drugs used most often, either by themselves or combined with other drugs. A chemotherapy agent is sometimes successfully infused into a limb to treat in-transit metastases (isolated limb perfusion) but this technique can have serious complications. Electrochemotherapy is a new treatment that uses electrical impulses to enhance effectiveness bleomycin or cisplatin injected directly into skin metastases. Even when chemotherapy shrinks these cancers, the cancer usually starts growing again within several months.

Some doctors may recommend biochemotherapy, which is a combination of chemotherapy and either interleukin-2, interferon, or both. This can often shrink tumors, which might make patients feel better, although it has not been shown to help patients live longer.

It’s important to carefully consider the possible benefits and side effects of any recommended treatment before starting it.

Because stage 4 melanoma is hard to cure with current treatments, patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial (https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials). Many studies are now looking at new targeted drugs, immunotherapies, chemotherapy drugs, and combinations of different types of treatments.

Even though stage 4 melanoma is often hard to cure, a small portion of people respond very well to treatment and survive for many years after diagnosis.

Targeted therapy drugs for melanoma skin cancer

About half of all melanomas have changes (mutations) in the BRAF gene. Melanoma cells with these changes make an altered BRAF protein that helps them grow. Some drugs target this and related proteins, such as the MEK proteins.

If you have melanoma that has spread beyond the skin, a biopsy sample of it will likely be tested to see if the cancer cells have a BRAF mutation. Drugs that target the BRAF protein (BRAF inhibitors) or the MEK proteins (MEK inhibitors) aren’t likely to work on melanomas that have a normal BRAF gene.

Most often, if a person has a BRAF mutation and needs targeted therapy, they will get both a BRAF inhibitor and a MEK inhibitor, as combining these drugs often works better than either one alone.

BRAF inhibitors

Some of the targeted cancer drugs for BRAF positive melanoma work by blocking the BRAF protein. They are called BRAF inhibitors. They can slow or stop the growth of the cancer.

Some of the BRAF inhibitors include:

- Vemurafenib (Zelboraf)

- Dabrafenib (Tafinlar)

- Encorafenib (Braftovi)

BRAF inhibitors are drugs that attack the BRAF protein directly. BRAF inhibitors can shrink or slow the growth of tumors in some people whose melanoma has spread or can’t be removed completely.

BRAF inhibitors are taken as pills or capsules, once or twice a day.

BRAF inhibitors common side effects can include skin thickening, rash, itching, sensitivity to the sun, headache, fever, joint pain, fatigue, hair loss, and nausea. Less common but serious side effects can include heart rhythm problems, liver problems, kidney failure, severe allergic reactions, severe skin or eye problems, bleeding, and increased blood sugar levels.

Some people treated with BRAF inhibitors develop new squamous cell skin cancers. These cancers are usually less serious than melanoma and can be treated by removing them. Still, your doctor will want to check your skin often during treatment and for several months afterward. You should also let your doctor know right away if you notice any new growths or abnormal areas on your skin.

MEK inhibitors

The BRAF protein can affect other proteins, such as MEK, which makes cancer cells divide and grow in an uncontrolled way. The MEK gene works together with the BRAF gene, so drugs that block MEK proteins can also help treat melanomas with BRAF gene changes. MEK inhibitors are another type of targeted cancer drug. MEK inhibitors work by blocking the MEK protein, which slows down the growth of cancer cells.

Two MEK inhibitors for melanoma are:

- Trametinib (Mekinist)

- Binimetinib (Mektovi)

- Cobimetinib (Cotellic)

MEK inhibitors can be used to treat melanoma that has spread or can’t be removed completely.

You usually have a BRAF inhibitor with a MEK inhibitor as having the combination of drugs can work better. This seems to shrink tumors for longer periods of time than using either type of drug alone. The usual combinations for melanoma include:

- dabrafenib with trametinib

- encorafenib and binimetinib

Some side effects (such as the development of other skin cancers) are actually less common with the combination.

MEK inhibitors are pills taken once or twice a day.

MEK inhibitors common side effects can include rash, nausea, diarrhea, swelling, and sensitivity to sunlight. Rare but serious side effects can include heart lung, or liver damage; bleeding or blood clots; vision problems; muscle damage; and skin infections.

Drugs that target cells with C-KIT gene changes

A small portion of melanomas have changes in the C-KIT gene that help them grow. These changes are more common in melanomas that start in certain parts of the body:

- On the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, or under the nails (known as acral melanomas)

- Inside the mouth or other mucosal (wet) areas

- In areas that get chronic sun exposure

Some targeted drugs, such as imatinib (Gleevec) and nilotinib (Tasigna), can affect cells with changes in C-KIT. If you have an advanced melanoma that started in one of these places, your doctor may test your melanoma cells for changes in the C-KIT gene, which might mean that one of these drugs could be helpful.

Drugs that target different gene changes are also being studied in clinical trials.

Immunotherapy for melanoma skin cancer

Immunotherapy is the use of medicines to help a person’s own immune system recognize and destroy melanoma cancer cells more effectively. You have immunotherapy if your melanoma is BRAF negative. If your melanoma is BRAF positive, you may have targeted cancer drugs or immunotherapy.

Several types of immunotherapy can be used to treat melanoma.

The immunotherapy drugs for melanoma are:

- Ipilimumab (Yervoy)

- Pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

- Nivolumab (Opdivo)

- Atezolizumab (Tecentriq)

You might have a combination of drugs such as nivolumab and ipilimumab.

These drugs are given as an intravenous (IV) infusion, typically every 2 to 6 weeks, depending on the drug and why it’s being given.

Some of the more common side effects of immunotherapy drugs can include fatigue, cough, nausea, skin rash, poor appetite, constipation, joint pain, and diarrhea.

Immunotherapy drugs more serious side effects but occur less often include:

- Infusion reactions: Some people might have an infusion reaction while getting these drugs. This is like an allergic reaction, and can include fever, chills, flushing of the face, rash, itchy skin, feeling dizzy, wheezing, and trouble breathing. It’s important to tell your doctor or nurse right away if you have any of these symptoms while getting these drugs.

- Autoimmune reactions: These drugs remove one of the safeguards on the body’s immune system. Sometimes the immune system responds by attacking other parts of the body, which can cause serious or even life-threatening problems in the lungs, intestines, liver, hormone-making glands, kidneys, or other organs.

It’s very important to report any new side effects to someone on your health care team as soon as possible. If serious side effects do occur, treatment may need to be stopped and you might be given high doses of corticosteroids to suppress your immune system.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

An important part of the immune system is its ability to keep itself from attacking normal cells in the body. To do this, it uses “checkpoints,” which are proteins on immune cells that need to be turned on (or off) to start an immune response. Melanoma cells sometimes use these checkpoints to avoid being attacked by the immune system. But these drugs target the checkpoint proteins, helping to restore the immune response against melanoma cells.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are now one of the mainstays of treatment for advanced melanomas. Researchers are now looking for ways to make these drugs work even better. One way to do this might be by combining them with other treatments, such as other types of immunotherapy or targeted drugs.

PD-1 inhibitors

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) are drugs that target PD-1, a protein on immune system cells called T cells that normally help keep these cells from attacking other cells in the body. By blocking PD-1, these drugs boost the immune response against melanoma cells. This can often shrink tumors and help people live longer.

They can be used to treat melanomas:

- That can’t be removed by surgery

- That have spread to other parts of the body

- After surgery (as adjuvant treatment) for certain stage 2 or 3 melanomas to try to lower the risk of the cancer coming back

These drugs are given as an intravenous (IV) infusion, typically every 2 to 6 weeks, depending on the drug and why it’s being given.

PD-L1 inhibitor

Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) is a drug that targets PD-L1, a protein related to PD-1 that is found on some tumor cells and immune cells. Blocking this protein can help boost the immune response against melanoma cells.

Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) can be used along with cobimetinib and vemurafenib in people with melanoma that has the BRAF gene mutation, when the cancer can’t be removed by surgery or has spread to other parts of the body.

This drug is given as an intravenous (IV) infusion every 2 to 4 weeks.

CTLA-4 inhibitor

Ipilimumab (Yervoy) is another drug that boosts the immune response, but it has a different target. It blocks CTLA-4, another protein on T cells that normally helps keep them in check.

It can be used to treat melanomas that can’t be removed by surgery or that have spread to other parts of the body. It might also be used for less advanced melanomas after surgery (as an adjuvant treatment) in some situations, to try to lower the risk of the cancer coming back.

When used alone, this drug doesn’t seem to shrink as many tumors as the PD-1 inhibitors, and it tends to have more serious side effects, so usually one of those other drugs is used first. Another option in some situations might be to combine this drug with one of the PD-1 inhibitors. This can increase the chance of shrinking the tumors (slightly more than a PD-1 inhibitor alone), but it can also increase the risk of side effects.

This drug is given as an intravenous (IV) infusion, usually once every 3 weeks for 4 treatments (although it may be given for longer when used as an adjuvant treatment).

LAG-3 inhibitor

Relatlimab targets LAG-3, another checkpoint protein on certain immune cells that normally helps keep the immune system in check.

This drug is given along with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab (in a combination known as Opdualag). It can be used to treat melanomas that can’t be removed by surgery or that have spread to other parts of the body.

This drug is given as an intravenous (IV) infusion, typically once every 4 weeks.

Talimogene laherparepvec (Imlygic or T-VEC)

Doctors might use another type of immunotherapy called talimogene laherparepvec (Imlygic), also known as T-VEC, which they inject directly into the melanoma, to treat melanomas in the skin or lymph nodes that can’t be removed with surgery. You might have talimogene laherparepvec (Imlygic or T-VEC) for melanoma that can’t be removed with surgery or has spread to certain areas of the body such as the lymph nodes or skin. Talimogene laherparepvec (Imlygic or T-VEC) is a weakened form of the cold sore virus. The changed virus grows in the cancer cells and destroys them. It also works by helping the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells. The virus is injected directly into the tumors, typically every 2 weeks. This treatment can sometimes shrink these tumors, and might also shrink tumors in other parts of the body.

Side effects of talimogene laherparepvec (Imlygic or T-VEC) can include flu-like symptoms and pain at the injection site.

Interleukin-2 (IL-2)

Interleukins are proteins that certain cells in the body make to boost the immune system in a general way. Lab-made versions of interleukin-2 (IL-2) are sometimes used to treat melanoma. They are given as intravenous (IV) infusions, at least at first. Some patients or caregivers may be able to learn how to give injections under the skin at home.

Interleukin-2 (IL-2) can sometimes shrink advanced melanomas when used alone. However, interleukin-2 (IL-2) is not used as much as in the past, because the immune checkpoint inhibitors are more likely to help people and tend to have fewer side effects. But interleukin-2 (IL-2) might be an option if these drugs are no longer working.

Side effects of interleukin-2 (IL-2) can include flu-like symptoms such as fever, chills, aches, severe tiredness, drowsiness, and low blood cell counts. In high doses, interleukin-2 (IL-2) can cause fluid to build up in the body so that the person swells up and can feel quite sick. Because of this and other possible serious side effects, high-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) is given only in the hospital, in centers that have experience with this type of treatment.

When deciding whether to use interleukin-2 (IL-2), patients and their doctors need to take into account the potential benefits and side effects of this treatment.

Melanoma vaccines

Vaccines to treat melanoma are being studied in clinical trials.

Melanoma vaccines are, in some ways, like the vaccines used to prevent diseases such as polio, measles, and mumps that are caused by viruses. Melanoma vaccines usually contain weakened viruses or parts of a virus that can’t cause the disease. The vaccine stimulates the body’s immune system to destroy the more harmful type of virus.

In the same way, killed melanoma cells or parts of cells (antigens) can be used as a vaccine to try to stimulate the body’s immune system to destroy other melanoma cells in the body. Usually, the cells or antigens are mixed with other substances that help boost the immune system as a whole. But unlike vaccines that are meant to prevent infections, these vaccines are meant to treat an existing disease.

Making an effective vaccine against melanoma has proven to be harder than making a vaccine to fight a virus. The results of studies using vaccines to treat melanoma have been mixed so far, but many newer vaccines are now being studied and may hold more promise.

Living with melanoma

When cancer treatment ends, people begin a new chapter in their lives, one that can bring hope and happiness, but also worries and fear. No two people are alike. Each person has their own way of coping and learning to manage these emotions. It will take time and practice. Getting practical and emotional support can help you cope with a diagnosis of melanoma, life during treatment and life after melanoma.

Follow-up after melanoma treatment

Your follow-up schedule should include regular skin and lymph node exams by yourself and by your doctor. How often you need follow-up doctor visits depends on the stage of your melanoma when you were diagnosed and other factors. People with melanoma that doesn’t go away completely with treatment will have a follow-up schedule that is based on their specific situation.

For stage 4 metastatic melanoma, a typical schedule might include physical exams every 3 to 6 months for several years. After that, exams might be done less often. Imaging tests such as ultrasounds or CT scans might be done as well, especially for people who had more advanced stage disease.

It’s also important for melanoma survivors to do regular self-exams of their skin and lymph nodes. Most doctors recommend this at least monthly. You should see your doctor if you find any new lump or change in your skin. You should also report any new symptoms (for example, pain, cough, fatigue, loss of appetite) that don’t go away. Melanoma can sometimes come back many years after it was first treated.

Coping

Coping with cancer can be difficult. Help and support are available, including things you can do, people that can help and ways to cope with a diagnosis of melanoma.

You may be more able to cope and make decisions if you have information about your type of cancer and its treatment. Information helps you to know what to expect.

Taking in information can be difficult, especially when you have just been diagnosed. Make a list of questions before you see your doctor. Take someone with you to remind you what you want to ask. They can also help you to remember the information that was given. Getting a lot of new information can feel overwhelming.

Ask your doctors and nurses to explain things again if you need them to.

Remember that you don’t have to sort everything out at once. It might take some time to deal with each issue. Ask for help if you need it.

Talking to other people

Talking to your friends and relatives about your cancer can help and support you. But some people are scared of the emotions this could bring up and won’t want to talk. They might worry that you won’t be able to cope with your situation.

It can strain relationships if your family or friends don’t want to talk. But talking can help increase trust and support between you and them.

Help your family and friends by letting them know if you would like to talk about what’s happening and how you feel.

You might find it easier to talk to someone outside your own friends and family. Or you may prefer to see a counselor. Some people feel better having a person-to-person connection with a counselor who can give one-on-one attention and encouragement. Your cancer care team may be able to recommend a counselor who works with cancer survivors.

Staying positive

In recent years, much attention has been paid to the importance of having a positive attitude. Some people go so far as to suggest that such an attitude will stop the cancer from growing or keep it from coming back. Please do not allow others’ misguided attempts to encourage positive thinking place this burden on you.

You might be better able to manage your life and cancer history when you’re able to look at things in a positive light, but that’s not always possible. It’s good to work toward having a positive attitude, which can help you feel better about life now. Just remember you don’t have to act “positive” all the time. Don’t beat yourself up or let others make you feel guilty when you’re feeling sad, angry, anxious, or distressed.

Cancer is not caused by a person’s negative attitude nor is it made worse by a person’s thoughts. Don’t let the positive attitude myths stop you from telling your loved ones or your cancer care team how you feel.

Learning to live with uncertainty

Here are some ideas that have helped others deal with uncertainty and fear and feel more hopeful:

- Be informed. Learn what you can do for your health now and about the services available to you. This can give you a greater sense of control.

- Be aware that you don’t have control over cancer recurrence. It helps to accept this rather than fight it.

- Be aware of your fears, but don’t judge them. Practice letting them go. It’s normal for these thoughts to enter your mind, but you don’t have to keep them there. Some people picture them floating away, or being vaporized. Others turn them over to a higher power to handle. However you do it, letting them go can free you from wasting time and energy on needless worry.

- Express your feelings of fear or uncertainty with a trusted friend or counselor. Being open and dealing with emotions helps many people feel less worried. People have found that when they express strong feelings, like fear, they’re better able to let go of these feelings. Thinking and talking about your feelings can be hard. But if you find cancer is taking over your life, it often helps to find a way to express your feelings.

- Take in the present moment rather than thinking of an uncertain future or a difficult past. If you can find a way to feel peaceful inside yourself, even for a few minutes a day, you can start to recall that peace when other things are happening – when life is busy and confusing.

- Use your energy to focus on wellness and what you can do now to stay as healthy as possible. Try to make healthy diet changes. If you are a person who smokes, this is a good time to quit.

- Find ways to help yourself relax.

- Be as physically active as you can.

- Control what you can. Some people say that putting their lives back in order makes them feel less fearful. Being involved in your health care, getting back to your normal life, and making changes in your lifestyle are among the things you can control. Even setting a daily schedule can give you more power. And while no one can control every thought, some say they’ve resolved not to dwell on the fearful ones.

Support groups

Some groups are formal and focus on learning about cancer or dealing with feelings. Others are informal and social. Some groups are made up of only people with cancer or only caregivers, while some include spouses, family members, or friends. Other groups focus on certain types of cancer or stages of disease. The length of time groups meet can range from a set number of weeks to an ongoing program. Some programs have closed membership and others are open to new, drop-in members.

It’s very important that you get information about any support group you are considering. Ask the group leader or facilitator what types of patients are in the group and if anyone in the group is dealing with survival after cancer.

Online support groups may be another option for support. The Cancer Survivors Network, an online support community supported by your American Cancer Society is just one example. You can visit this community at https://csn.cancer.org. There are many other good communities on the Internet that you can join as well, although you’ll want to check them out before joining.

References- Swavey S, Tran M. Porphyrin and phthalocyanine photosensitizers as PDT agents: a new modality for the treatment of melanoma. In Tech. 2013. doi:10.5772/54940

- Melanoma of the vulva and vagina: principles of staging and their relevance to management based on a clinicopathologic analysis of 85 cases. Seifried S, Haydu LE, Quinn MJ, Scolyer RA, Stretch JR, Thompson JF. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015; 22(6):1959-66.

- Melanoma. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/melanoma

- Emerging trends in the epidemiology of melanoma. Nikolaou V, Stratigos AJ. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jan; 170(1):11-9.

- Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Ipilimumab Versus Placebo After Complete Resection of Stage III Melanoma: Initial Efficacy and Safety Results From the EORTC 18071 Phase III Trial. Alexandria, VA: The Journal of Clinical Oncology; 2014. doi:10.1200/jco.2014.32.18_suppl.lba9008

- About advanced melanoma. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/melanoma/advanced-melanoma/about-advanced-melanoma

- Contreras-Steyls M, Herrera-Acosta E, Moyano B, Herrera E. Melanoma primario con metástasis cutáneas múltiples [Primary melanoma with multiple skin metastases]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011 Apr;102(3):226-9. Spanish. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2010.06.025

- Cutaneous metastases. https://www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/skin-metastases

- Melanoma Skin Cancer Stages. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/melanoma-skin-cancer-stages.html

- Melanoma of the Skin — Cancer Stat Facts. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html

- Survival Rates for Melanoma Skin Cancer, by Stage. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates-for-melanoma-skin-cancer-by-stage.html

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong S, et al. Final Version of 2009 AJCC Melanoma Staging and Classification. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(36):6199-6206. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2793035/

- Treatment of Melanoma Skin Cancer, by Stage. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/treating/by-stage.html