Muenke syndrome

Muenke syndrome also known as Muenke nonsyndromic coronal craniosynostosis or FGFR3-associated coronal synostosis syndrome, a genetic disorder characterized by the premature closure of certain bones of the skull (craniosynostosis) during development, which affects the shape of the head and face. Muenke syndrome accounts for an estimated 4 percent of all cases of craniosynostosis 1. Many people with Muenke syndrome have a premature fusion of skull bones along the coronal suture (coronal craniosynostosis), the growth line that goes over the head from ear to ear. Other parts of the skull may also be malformed. These changes can result in an abnormally shaped head, wide-set eyes, and flattened cheekbones. About 5 percent of affected individuals have an enlarged head (macrocephaly). People with Muenke syndrome may also have mild abnormalities of the hands or feet, and hearing loss has been observed in some cases. Most people with Muenke syndrome have normal intellect, but developmental delay and learning problems are possible.

The signs and symptoms of Muenke syndrome vary among affected people, and some features overlap with those seen in other craniosynostosis syndromes. A small percentage of people with the gene mutation associated with Muenke syndrome do not have any of the characteristic features of the disorder.

Muenke syndrome occurs in about 1 in 30,000 newborns 1.

Children with Muenke syndrome and craniosynostosis are best managed by a pediatric craniofacial clinic that typically includes a craniofacial surgeon and neurosurgeon, clinical geneticist, ophthalmologist, otolaryngologist, pediatrician, radiologist, psychologist, dentist, audiologist, speech therapist, and social worker 2. Depending on severity, the first craniosynostosis repair (fronto-orbital advancement and cranial vault remodeling) is typically performed between ages three and six months. An alternative approach is endoscopic strip craniectomy, which is a less invasive procedure and is typically performed prior to age three months.

Postoperative increased intracranial pressure and/or the need for secondary or tertiary extracranial contouring may occur. The need for secondary revision procedures is inversely related to the age of the affected individual at the time of initial repair. The location of the fused/synostotic suture, type of fixation, and the use of bone grafting do not have a significant effect on the need for revision.

Standard treatments for sensorineural hearing loss; early speech therapy and intervention programs for those with developmental delay, intellectual impairment, behavioral problems, and/or hearing loss; surgical correction for strabismus; lubrication for exposure keratopathy 2.

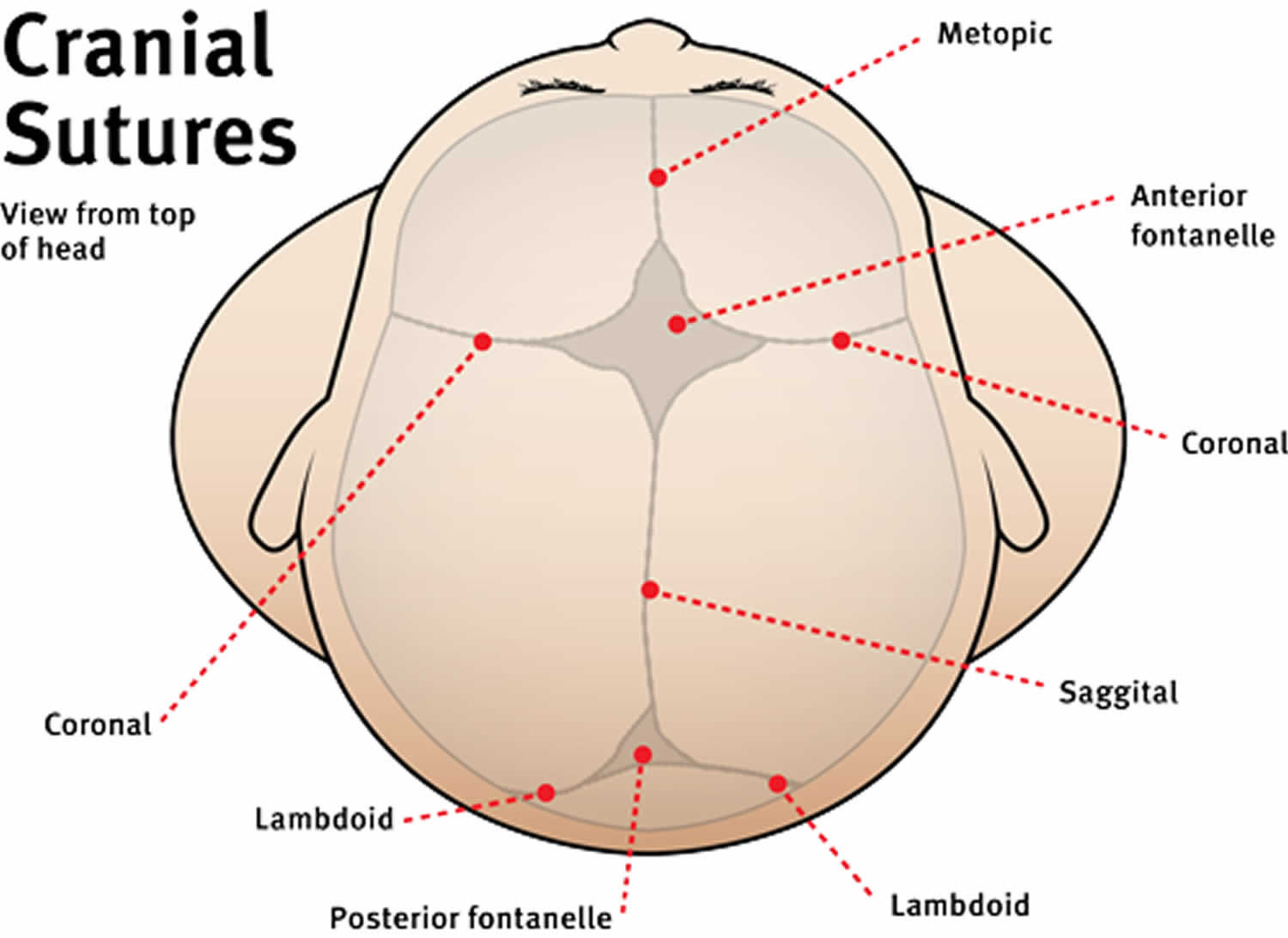

Figure 1. Cranial sutures of babies

Figure 2. Muenke syndrome

Footnote: 4-month-old with Muenke syndrome. Note the temporal bossing (prominence at the temple region), tall head shape and wide-spaced eyes.

Muenke syndrome causes

Mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene causes Muenke syndrome. The FGFR3 gene provides instructions for making a protein that is involved in the development and maintenance of bone and brain tissue. The mutation associated with Muenke syndrome causes the FGFR3 protein to be overly active, which interferes with normal bone growth and allows the bones of the skull to fuse before they should.

Muenke syndrome inheritance pattern

Muenke syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder.

Often autosomal dominant conditions can be seen in multiple generations within the family. If one looks back through their family history they notice their mother, grandfather, aunt/uncle, etc., all had the same condition. In cases where the autosomal dominant condition does run in the family, the chance for an affected person to have a child with the same condition is 50% regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

- When one parent has the abnormal gene, they will pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. Each of their children therefore has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting the changed gene and being affected by the condition.

- There is also a 50% (1 in 2) chance that a child will inherit the normal copy of the gene. If this happens the child will not be affected by the disorder and cannot pass it on to any of his or her children.

Figure 3 illustrates autosomal dominant inheritance. The example below shows what happens when dad has the condition, but the chances of having a child with the condition would be the same if mom had the condition.

Figure 3. Muenke syndrome autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Muenke syndrome symptoms

Individuals with Muenke syndrome typically have the following conditions:

- Craniosynostosis: early closure of one or more of the seams between the skull bones, causing an abnormal skull. This results in a skull shape with increased vertical height. Typically, one or both coronal sutures (the seams that run from ear to ear over top of the head and meet at the soft spot in the middle) are fused, causing a very tall forehead and wide, short skull.

- Midface hypoplasia: decreased growth of the midface. This does not typically contribute to obstructive sleep apnea and airway concerns.

- Hypertelorism: wide-set eyes.

The signs and symptoms of Muenke syndrome vary among affected people, and some findings overlap with those seen in other craniosynostosis syndromes. Between 6 percent and 7 percent of people with the FGFR3 gene mutation do not have any of the characteristic features of the disorder 1.

Many people with Muenke syndrome have a premature fusion of skull bones along the coronal suture, the growth line which goes over the head from ear to ear. Other parts of the skull may be affected as well. These changes can result in an abnormally shaped head, temporal bossing, wide-set eyes, ptosis or proptosis (usually mild), strabismus, flattened cheekbones, midface retrusion (usually mild) and highly arched palate or cleft lip and palate. Unilateral coronal synostosis results in anterior plagiocephaly (asymmetry of the skull and face). About 5 percent of affected individuals have an enlarged head (macrocephaly). Some people with Muenke syndrome have mild abnormalities of the hands or feet 1. Hearing loss is present in about one third of patients 2. While most people with Muenke syndrome have normal intellect, developmental delay and learning disabilities have been reported 3. Compared to normative populations, individuals with Muenke syndrome have also been reported to be at increased risk for developing some behavioral and emotional problems 4.

In a large international study of Muenke syndrome, 40.8% were reported to have intellectual disability and 66.3% had developmental delay, with speech delay the most common type (61.1%) 5. Approximately 24% had a diagnosis of ADHD.

Muenke syndrome complications

Patients with Muenke syndrome may be at greater risk for elevated intracranial pressure than other syndromes, and hearing loss is much more frequently encountered. Early surgical reconstruction for craniosynostosis may reduce the risk for complications including complications related to increased intracranial pressure (e.g., behavioral changes) 2.

Muenke syndrome diagnosis

Although the diagnosis of Muenke syndrome is suggested by clinical findings, it is established by the presence of the FGFR3 gene mutation.

Muenke syndrome should be suspected in individuals with the following clinical and radiographic findings.

Clinical features

- Facial asymmetry

- Brachycephaly (reduced anteroposterior dimension of the skull), turribrachycephaly (a “tower-shaped” skull), or cloverleaf skull

- Sutural ridging over both (or less commonly one) of the coronal sutures accompanied by:

- Ipsilateral

- Flattening of the forehead

- Elevation of the superior orbital rim

- Elevation of the eyebrow

- Anterior placement of the ear

- Deviation of the nasal root

- Contralateral

- Frontal bossing of the forehead

- Depression of the eyebrow

- Ipsilateral

- Temporal bossing

- Macrocephaly without craniosynostosis

- Craniosynostosis with sensorineural hearing loss

Radiographic findings

- Head CT with three-dimensional reconstruction demonstrating:

- Unilateral coronal craniosynostosis

- Bilateral coronal craniosynostosis

- Synostosis of other sutures (lambdoid, metopic, sagittal, squamosal)

- Extracranial radiographic features can include:

Muenke syndrome treatment

The treatment of Muenke syndrome is dependent upon both functional and appearance-related needs, and should be addressed immediately after your child is born. Because of the complex issues that can be associated with Muenke syndrome, your child should be treated at a medical center that includes the pediatric specialists across the many clinical areas your child may need. Children with Muenke syndrome are best managed by a pediatric craniofacial clinic where a team of health care professionals, including a craniofacial surgeon and neurosurgeon, medical geneticist, ophthalmologist, otolaryngologist, pediatrician, radiologist, psychologist, dentist, audiologist, speech therapist, and social worker may work to address their individuals needs.

Because every patient with syndromic craniosynostosis has unique problems, the timing and course of surgical treatment is highly individualized. It is important to see a surgeon with expertise in pediatric plastic and reconstructive surgery who specializes in treating these rare conditions.

Depending on severity, the first craniosynostosis repair may be performed between ages three and six months. Early surgery may reduce the risk for complications. Follow-up surgeries and/or other medical procedures may be needed 2.

As your child grows, she should also have access to psychosocial support services to address any mental, social or psychological issues that accompany these conditions.

Muenke syndrome prognosis

Following craniosynostosis repair, the need for a second procedure is increased in those with Muenke syndrome compared to those with craniosynostosis without the defining pathogenic variant. The reasons for a second procedure vary by individual and can include:

- Severe initial clinical presentation requiring a staged repair

- Cranial vault abnormalities including temporal bulging and recurrent supraorbital retrusion requiring extracranial contouring (i.e., use of a cement such as calcium phosphate to contour the surface of the skull)

- Postoperative increased intracranial pressure

- Recurrent deformity requiring a second transcranial repair:

- The need for a surgical revision for aesthetic reasons (typically temporal bulging) has been reported in multiple series 9.

- According to Thomas et al 10, individuals with craniosynostosis and the defining pathogenic variant for Muenke syndrome were more likely to require early intervention with a posterior release operation (at age ~6 months) to prevent excess frontal bulging than were those without the defining pathogenic variant.

- Seven (24.1%) of 29 individuals with the p.Pro250Arg pathogenic variant underwent a second surgery (6/7 had increased intracranial pressure) as compared to two (4.3%) of 47 without the pathogenic variant. This difference in reoperation rate was statistically significant 10.

- In the report of Honnebier et al 9, 16 individuals with Muenke syndrome required a second procedure: seven required a second transcranial procedure; 15 were expected to undergo extracranial contouring. Note that none had increased intracranial pressure.

- However, a study by Ridgway et al 11 challenges the above findings, reporting a frequency of frontal revision in individuals with Muenke syndrome who had fronto-orbital advancements that was lower than previously reported. This study found that the need for secondary revision procedures was inversely related to the age of the affected individual at the time of the initial repair. The location of the fused/synostotic suture, type of fixation, and the use of bone grafting do not have a significant effect on the need for revision.

In Muenke syndrome a discrepancy between severity of the craniofacial findings (e.g., severe midface retrusion, widely spaced eyes) and neurologic findings (e.g., increased intracranial pressure, hydrocephalus, structural brain anomalies, severe developmental delay, or severe intellectual disability) has been noted 9: severe early clinical findings such as recurrent deformity and the need for a second major procedure did not correlate with postoperative risk for increased intracranial pressure.

Hearing loss

Hearing loss is often sensorineural. Standard treatments for hearing loss apply, including special accommodations for school-aged children, hearing aids, and (potentially) cochlear implants 12.

Developmental delay

Individuals with Muenke syndrome are at increased risk for behavioral problems, intellectual disability, and developmental delay 4; thus, referral for speech therapy and early intervention is indicated. Referral to a developmental and/or behavioral specialist for assessment and treatment is recommended.

Ocular abnormalities

- Strabismus surgery/correction is indicated to prevent amblyopia.

- Because surgical correction of craniosynostosis is a priority, delay in strabismus surgery in the first two years of life is common; however, earlier correction of strabismus should be considered to achieve binocularity.

- In those with proptosis, lubrication for exposure keratopathy is indicated.

- Muenke syndrome. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/muenke-syndrome

- Kruszka P, Addissie YA, Agochukwu NB, et al. Muenke Syndrome. 2006 May 10 [Updated 2016 Nov 10]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1415

- Kress W, Schropp C, Lieb G, Petersen B, Busse-Ratzka M, Kunz J, Reinhart E, Schafer WD, Sold J, Hoppe F, Pahnke J, Trusen A, Sorensen N, Krauss J, Collmann H. Saethre-Chotzen syndrome caused by TWIST 1 gene mutations: functional differentiation from Muenke coronal synostosis syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:39–48.

- Yarnell CM, Addissie YA, Hadley DW, Guillen Sacoto MJ, Agochukwu NB, Hart RA, Wiggs EA, Platte P, Paelecke Y, Collmann H, Schweitzer T, Kruszka P, Muenke M. Executive Function and Adaptive Behavior in Muenke Syndrome. J Pediatr. 2015;167:428–34.

- Kruszka P, Addissie YA, Yarnell CM, Hadley DW, Guillen Sacoto MJ, Platte P, Paelecke Y, Collmann H, Snow N, Schweitzer T, Boyadjiev SA, Aravidis C, Hall SE, Mulliken JB, Roscioli T, Muenke M. Muenke syndrome: An international multicenter natural history study. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A:918–29.

- Agochukwu NB, Solomon BD, Benson LJ, Muenke M. Talocalcaneal coalition in Muenke syndrome: report of a patient, review of the literature in FGFR-related craniosynostoses, and consideration of mechanism. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:453–60.

- Muenke M, Gripp KW, McDonald-McGinn DM, Gaudenz K, Whitaker LA, Bartlett SP, Markowitz RI, Robin NH, Nwokoro N, Mulvihill JJ, Losken HW, Mulliken JB, Guttmacher AE, Wilroy RS, Clarke LA, Hollway G, Ades LC, Haan EA, Mulley JC, Cohen MM Jr, Bellus GA, Francomano CA, Moloney DM, Wall SA, Wilkie AO, Zackai EH. A unique point mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 gene (FGFR3) defines a new craniosynostosis syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:555–64.

- Graham JM Jr, Braddock SR, Mortier GR, Lachman R, Van Dop C, Jabs EW. Syndrome of coronal craniosynostosis with brachydactyly and carpal/tarsal coalition due to Pro250Arg mutation in FGFR3 gene. Am J Med Genet. 1998;77:322–9.

- Honnebier MB, Cabiling DS, Hetlinger M, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, Bartlett SP. The natural history of patients treated for FGFR3-associated (Muenke-type) craniosynostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:919–31.

- Thomas GP, Wilkie AO, Richards PG, Wall SA. FGFR3 P250R mutation increases the risk of reoperation in apparent “nonsyndromic” coronal craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:347–52.

- Ridgway EB, Wu JK, Sullivan SR, Vasudavan S, Padwa BL, Rogers GF, Mulliken JB. Craniofacial growth in patients with FGFR3 Pro250Arg mutation after fronto-orbital advancement in infancy. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:455–61.

- Agochukwu NB, Solomon BD, Muenke M. Hearing loss in syndromic craniosynostoses: otologic manifestations and clinical findings. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014b;78:2037–47