Acute myelogenous leukemia

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is a cancer of the blood cells and bone marrow — the spongy tissue inside bones where blood cells are made. AML is not a single disease. Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the name given to a group of leukemias that develop in the myeloid cell line in the bone marrow. The word “acute” in acute myelogenous leukemia denotes the disease’s rapid progression. It’s called myelogenous leukemia because it affects a group of white blood cells called the myeloid cells, which normally develop into the various types of mature blood cells, such as red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets excluding lymphocytes. In acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), there are too many of a specific type of immature white blood cells called a myeloblasts or leukemic blasts. These immature white blood cells the bone marrow, preventing it from making normal blood cells. They can also spill out into the bloodstream and circulate around the body. Due to their immaturity they are unable to function properly to prevent or fight infection. Inadequate numbers of red cells and platelets being made by the marrow can cause anemia, easy bleeding, and/or bruising.

Acute myelogenous leukemia is also known as acute myeloid leukemia, acute myeloblastic leukemia, acute granulocytic leukemia and acute nonlymphocytic leukemia.

AML is the most common type of acute leukemia in adults. Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) cancer usually gets worse quickly if it is not treated. Possible risk factors include smoking, previous chemotherapy treatment, and exposure to radiation.

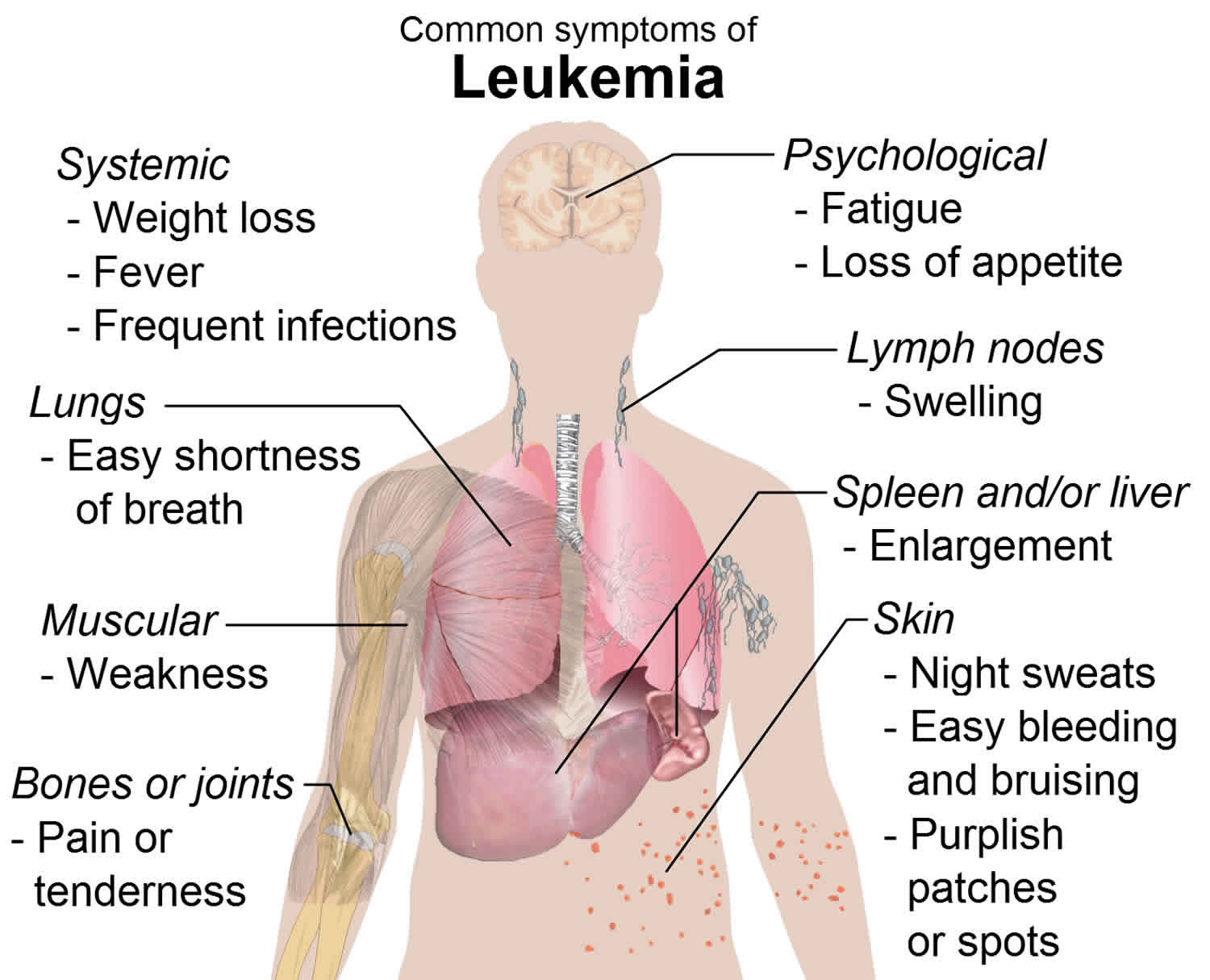

Symptoms of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) include:

- Fever

- Shortness of breath

- Easy bruising or bleeding

- Bleeding under the skin

- Weakness or feeling tired

- Weight loss or loss of appetite

Tests that examine the blood and bone marrow diagnose acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Treatments include chemotherapy, other drugs, radiation therapy, stem cell transplants, and targeted therapy. Targeted therapy uses substances that attack cancer cells without harming normal cells. Once the leukemia is in remission, you need additional treatment to make sure that it does not come back.

Figure 1. Blood cells production in bone marrow

Figure 2. Blood cells development

Acute myelogenous leukemia types

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is classified into eight different subtypes based on the appearance of the leukemic cells under the microscope. Two of the main systems that have been used to classify AML into subtypes are the French-American-British (FAB) classification and the newer World Health Organization (WHO) classification. Each subtype provides information on the type of blood cell involved and the point at which it stopped maturing properly in the bone marrow. This is known as the French-American-British (FAB) classification system.

The current World Health Organisation’s classification system for AML uses additional information obtained from more specialised laboratory techniques, like genetic studies, to classify AML more precisely. This information also provides more reliable information regarding the likely course (prognosis), of a particular subtype of AML, and the best way to treat it.

Some subtypes of AML are associated with specific symptoms, for example, acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APML or M3) is associated with bleeding and abnormalities in blood clotting.

The French-American-British (FAB) classification of AML

In the 1970s, a group of French, American, and British leukemia experts divided AML into subtypes, M0 through M7, based on the type of cell the leukemia develops from and how mature the cells are. This was based largely on how the leukemia cells looked under the microscope after routine staining.

Subtypes M0 through M5 all start in immature forms of white blood cells. M6 AML starts in very immature forms of red blood cells, while M7 AML starts in immature forms of cells that make platelets.

Table 1. The French, American, and British leukemia classification of AML

| FAB subtype | Name |

| M0 | Undifferentiated acute myeloblastic leukemia |

| M1 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia with minimal maturation |

| M2 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia with maturation |

| M3 | Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) |

| M4 | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia |

| M4 eos | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia with eosinophilia |

| M5 | Acute monocytic leukemia |

| M6 | Acute erythroid leukemia |

| M7 | Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia |

World Health Organization (WHO) classification of AML

The FAB classification system can be useful, but it doesn’t take into account many of the factors that are now known to affect prognosis (outlook). The World Health Organization (WHO) system, most recently updated in 2016, includes some of these factors to try to better classify AML.

The WHO system divides AML into several groups:

AML with certain genetic abnormalities (gene or chromosome changes)

- AML with a translocation between chromosomes 8 and 21 [t(8;21)]

- AML with a translocation or inversion in chromosome 16 [t(16;16) or inv(16)]

- APL with the PML-RARA fusion gene

- AML with a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 11 [t(9;11)]

- AML with a translocation between chromosomes 6 and 9 [t(6:9)]

- AML with a translocation or inversion in chromosome 3 [t(3;3) or inv(3)]

- AML (megakaryoblastic) with a translocation between chromosomes 1 and 22 [t(1:22)]

- AML with the BCR-ABL1 (BCR-ABL) fusion gene*

- AML with mutated NPM1 gene

- AML with biallelic mutations of the CEBPA gene (that is, mutations in both copies of the gene)

- AML with mutated RUNX1 gene*

*This is still a “provisional entity,” meaning it’s not yet clear if there’s enough evidence that it’s a unique group.

AML with myelodysplasia-related changes

AML related to previous chemotherapy or radiation

AML not otherwise specified (This includes cases of AML that don’t fall into one of the above groups, and is similar to the FAB classification.)

- AML with minimal differentiation (FAB M0)

- AML without maturation (FAB M1)

- AML with maturation (FAB M2)

- Acute myelomonocytic leukemia (FAB M4)

- Acute monoblastic/monocytic leukemia (FAB M5)

- Pure erythroid leukemia (FAB M6)

- Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (FAB M7)

- Acute basophilic leukemia

- Acute panmyelosis with fibrosis

Myeloid sarcoma (also known as granulocytic sarcoma or chloroma)

Myeloid proliferations related to Down syndrome

Undifferentiated and biphenotypic acute leukemias are not strictly AML, but are leukemias that have both lymphocytic and myeloid features. They are sometimes called mixed phenotype acute leukemias (MPALs).

Acute myelogenous leukemia causes

Acute myelogenous leukemia is caused by damage to the DNA of developing cells in your bone marrow. When this happens, blood cell production goes wrong. The bone marrow produces immature cells that develop into leukemic white blood cells called myeloblasts. These abnormal cells are unable to function properly, and they can build up and crowd out healthy cells. In most cases, it’s not clear what causes the DNA mutations that lead to leukemia. Radiation, exposure to certain chemicals and some chemotherapy drugs are known risk factors for acute myelogenous leukemia.

Mutations in many different genes can be found in AML, but larger changes in one or more chromosomes are also common. Even though these changes involve larger pieces of DNA, their effects are still likely to be due to changes in just one or a few genes that are on that part of the chromosome. Several types of chromosome changes may be found in AML cells:

- Translocations are the most common type of chromosome change. A translocation means that a part of one chromosome breaks off and becomes attached to a different chromosome. The point at which the break occurs can affect nearby genes – for example, it can turn on oncogenes or turn off genes like RUNX1 and RARa, which would normally help blood cells to mature.

- Deletions occur when part of a chromosome is lost. This can result in the cell losing a gene that helped keep its growth in check (a tumor suppressor gene).

- Inversions occur when part of a chromosome gets turned around, so it’s now in reverse order. This can result in the loss of a gene (or genes) because the cell can no longer read its instructions (much like trying to read a book backward).

- Addition or duplication means that there is an extra chromosome or part of a chromosome. This can lead to too many copies of certain genes within the cell. This can be a problem if one or more of these genes are oncogenes.

There are many types of AML, and different cases of AML can have different gene and chromosome changes, some of which are more common than others. Doctors are trying to figure out why these changes occur and how each of them might lead to leukemia. For example, some are more common in leukemia that occurs after chemotherapy for another cancer.

Some changes seem to have more of an effect on a person’s prognosis (outlook) than others. For instance, some changes might affect how quickly the leukemia cells grow, or how likely they are to respond to treatment.

Risk factors for developing acute myelogenous leukemia

Factors that may increase your risk of acute myelogenous leukemia include:

- Increasing age. The risk of acute myelogenous leukemia increases with age. Acute myelogenous leukemia is most common in adults age 65 and older.

- Your sex. Men are more likely to develop acute myelogenous leukemia than are women.

- Previous cancer treatment. People who’ve had certain types of chemotherapy and radiation therapy may have a greater risk of developing AML.

- Exposure to radiation. People exposed to very high levels of radiation, such as survivors of a nuclear reactor accident, have an increased risk of developing AML.

- Dangerous chemical exposure. Exposure to certain chemicals, such as benzene, is linked to a greater risk of AML.

- Smoking. AML is linked to cigarette smoke, which contains benzene and other known cancer-causing chemicals.

- Other blood disorders. People who’ve had another blood disorder, such as myelodysplastic syndromes, myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera or thrombocythemia, aplastic anemia and paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria, are at greater risk of developing AML.

- Having a family history of AML. Although most cases of AML are not thought to have a strong genetic link, having a close relative (such as a parent, brother, or sister) with AML increases your risk of getting the disease.Someone who has an identical twin who got AML before they were a year old has a very high risk of also getting AML.

- Genetic disorders. Certain genetic disorders, such as Down syndrome (being born with an extra copy of chromosome 21) and Trisomy 8 (being born with an extra copy of chromosome 8), are associated with an increased risk of AML.

- Some syndromes that are caused by genetic mutations (abnormal changes) present at birth seem to raise the risk of AML. These include:

- Fanconi anemia

- Bloom syndrome

- Ataxia-telangiectasia

- Diamond-Blackfan anemia

- Schwachman-Diamond syndrome

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome

- Neurofibromatosis type 1

- Severe congenital neutropenia (also called Kostmann syndrome)

Many people with AML have no known risk factors, and many people who have risk factors never develop the cancer.

Acute myelogenous leukemia symptoms

General signs and symptoms of the early stages of acute myelogenous leukemia may mimic those of the flu or other common diseases. Signs and symptoms may vary based on the type of blood cell affected.

Signs and symptoms of acute myelogenous leukemia include:

- Fever

- Bone pain

- Lethargy and fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Pale skin

- Frequent infections

- Easy bruising

- Unusual bleeding, such as frequent nosebleeds and bleeding from the gums

Symptoms from low red blood cell counts (anemia)

Red blood cells carry oxygen to all of the cells in the body. A shortage of red blood cells can cause:

- Tiredness (fatigue)

- Weakness

- Feeling cold

- Feeling dizzy or lightheaded

- Headaches

- Pale skin

- Shortness of breath

Symptoms from low white blood cell counts

Infections can occur because of a shortage of normal white blood cells (leukopenia), specifically a shortage of infection-fighting white blood cells called neutrophils (a condition called neutropenia). People with AML can get infections that don’t seem to go away or may get one infection after another. Fever often goes along with the infection.

Although people with AML can have high white blood cell counts due to excess numbers of leukemia cells, these cells don’t protect against infection the way normal white blood cells do.

Symptoms from low blood platelet counts

Platelets normally help stop bleeding. A shortage of blood platelets (called thrombocytopenia) can lead to:

- Bruises (or small red or purple spots) on the skin

- Excess bleeding

- Frequent or severe nosebleeds

- Bleeding gums

- Heavy periods (menstrual bleeding) in women

Symptoms caused by high numbers of leukemia cells

The cancer cells in AML (called blasts) are bigger than normal white blood cells and have more trouble going through tiny blood vessels. If the blast count gets very high, these cells can clog up blood vessels and make it hard for normal red blood cells (and oxygen) to get to tissues. This is called leukostasis. Leukostasis is rare, but it is a medical emergency that needs to be treated right away. Some of the symptoms are like those seen with a stroke, and include:

- Headache

- Weakness in one side of the body

- Slurred speech

- Confusion

- Sleepiness

When blood vessels in the lungs are affected, people can have shortness of breath. Blood vessels in the eye can be affected as well, leading to blurry vision or even loss of vision.

Bleeding and clotting problems

- Patients with a certain type of AML called acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) might have problems with bleeding and blood clotting. They might have a nosebleed that won’t stop, or a cut that won’t stop oozing. They might also have calf swelling from a blood clot called a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or chest pain and shortness of breath from a blood clot in the lung (called a pulmonary embolism or PE).

Bone or joint pain

- Some people with AML have bone pain or joint pain caused by the buildup of leukemia cells in these areas.

Swelling in the abdomen

- Leukemia cells may build up in the liver and spleen, making them larger. This may be noticed as a fullness or swelling of the belly. The lower ribs usually cover these organs, but when they are enlarged the doctor can feel them.

Symptoms caused by leukemia spread

Spread to the skin

- If leukemia cells spread to the skin, they can cause lumps or spots that may look like common rashes. A tumor-like collection of AML cells under the skin or other parts of the body is called a chloroma, granulocytic sarcoma, or myeloid sarcoma. Rarely, AML will first appear as a chloroma, with no leukemia cells in the bone marrow.

Spread to the gums

Certain types of AML may spread to the gums, causing swelling, pain, and bleeding.

Spread to other organs

Less often, leukemia cells can spread to other organs. Spread to the brain and spinal cord can cause symptoms such as:

- Headaches

- Weakness

- Seizures

- Vomiting

- Trouble with balance

- Facial numbness

- Blurred vision

On rare occasions AML can spread to the eyes, testicles, kidneys, or other organs.

Enlarged lymph nodes

Rarely, AML can spread to lymph nodes (bean-sized collections of immune cells throughout the body), making them bigger. Affected nodes in the neck, groin, underarm areas, or above the collarbone may be felt as lumps under the skin.

Although any of the symptoms and signs above may be caused by AML, they can also be caused by other conditions. Still, if you have any of these problems, especially if they don’t go away or are getting worse, it’s important to see a doctor so the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

Acute myelogenous leukemia diagnosis

If you have signs or symptoms of acute myelogenous leukemia, your doctor may recommend that you undergo diagnostic tests, including:

- Blood tests. Most people with acute myelogenous leukemia have too many white blood cells, not enough red blood cells and not enough platelets. The presence of blast cells — immature cells normally found in bone marrow but not circulating in the blood — is another indicator of acute myelogenous leukemia.

- Bone marrow test. A blood test can suggest leukemia, but it usually takes a bone marrow test to confirm the diagnosis. During a bone marrow biopsy, a needle is used to remove a sample of your bone marrow. Usually, the sample is taken from your hipbone (posterior iliac crest). The sample is sent to a laboratory for testing.

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap). In some cases, it may be necessary to remove some of the fluid around your spinal cord to check for leukemia cells. Your doctor can collect this fluid by inserting a small needle into the spinal canal in your lower back.

- Genomic testing. Laboratory tests of your leukemia cells can identify specific genes, chromosome changes, and other issues unique to your leukemia, as well as to find genetic changes or mutations. This can help determine your prognosis and guide your treatment.

If your doctor suspects leukemia, you may be referred to a doctor who specializes in blood cancer (hematologist or medical oncologist).

Determining your AML subtype

If your doctor determines that you have AML, you may need further tests to determine the extent of the cancer and classify it into a more specific AML subtype.

Your AML subtype is based on how your cells appear when examined under a microscope. Special laboratory testing also may be used to identify the specific characteristics of your cells.

Your AML subtype helps determine which treatments may be best for you. Doctors are studying how different types of cancer treatment affect people with different AML subtypes.

Acute myelogenous leukemia treatment

Treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia depends on several factors, including the subtype of the disease, your age, your overall health and your preferences.

In general, AML treatment falls into two phases:

- Remission induction therapy. The purpose of the first phase of treatment is to kill the leukemia cells in your blood and bone marrow. However, remission induction usually doesn’t wipe out all of the leukemia cells, so you need further treatment to prevent the disease from returning.

- Consolidation therapy. Also called post-remission therapy, maintenance therapy or intensification, this phase of treatment is aimed at destroying the remaining leukemia cells. It’s considered crucial to decreasing the risk of relapse.

Therapies used in these phases include:

- Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy is the major form of remission induction therapy, though it can also be used for consolidation therapy. Chemotherapy uses chemicals to kill cancer cells in your body. People with AML generally stay in the hospital during chemotherapy treatments because the drugs destroy many normal blood cells in the process of killing leukemia cells. If the first cycle of chemotherapy doesn’t cause remission, it can be repeated.

- Targeted therapy. Targeted therapy uses drugs that attack specific vulnerabilities within your cancer cells. The drug midostaurin (Rydapt) stops the action of an enzyme within the leukemia cells and causes the cells to die. Midostaurin is only useful for people whose cancer cells have the FLT3 mutation. This drug is administered in pill form.

- Other drug therapy. Arsenic trioxide (Trisenox) and all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) are anti-cancer drugs that can be used alone or in combination with chemotherapy for remission induction of a certain subtype of AML called promyelocytic leukemia. These drugs cause leukemia cells with a specific gene mutation to mature and die, or to stop dividing.

- Bone marrow transplant. A bone marrow transplant, also called a stem cell transplant, may be used for consolidation therapy. A bone marrow transplant helps re-establish healthy stem cells by replacing unhealthy bone marrow with leukemia-free stem cells that will regenerate healthy bone marrow. Prior to a bone marrow transplant, you receive very high doses of chemotherapy or radiation therapy to destroy your leukemia-producing bone marrow. Then you receive infusions of stem cells from a compatible donor (allogeneic transplant). You can also receive your own stem cells (autologous transplant) if you were previously in remission and had your healthy stem cells removed and stored for a future transplant.

- Clinical trials. Some people with leukemia choose to enroll in clinical trials to try experimental treatments or new combinations of known therapies.

Acute myelogenous leukemia prognosis

Acute myelogenous leukemia is an aggressive form of cancer that typically demands quick decision-making. The most important factor in predicting prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the genetic make-up of the leukemic cells. Certain cytogenetic changes are associated with a more favorable prognosis than others. This means that they are more likely to respond well to treatment, and may even be cured.

Favorable cytogenetic changes include: a translocation between chromosome 8 and 21 t(8;21), inversion of chromosome 16; inv(16) and a translocation between chromosome 15 and 17; t(15;17). This final change is found in AML subtype acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML or M3). APML is treated differently to other types of AML, and usually has the best overall prognosis.

Other cytogenetic changes are associated with an average or intermediate prognosis, while others are associated with a poor, or unfavorable prognosis. It is important to note that in most cases of AML, neither ‘good’ nor ‘bad-risk’ cytogenetic changes are found. People with ‘normal’ cytogenetics are also regarded as having an average prognosis.

Prognostic factors for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML)

The subtype of acute myelogenous leukemia can be important in helping to determine a person’s prognosis (outlook). But other factors can also affect why some patients with AML have a better outlook than others. These are called prognostic factors. Prognostic factors help doctors determine a person’s risk of the leukemia coming back after treatment, and therefore if they should get more or less intensive treatment. Some of these include:

Chromosome (cytogenetic) abnormalities

AML cells can have many kinds of chromosome changes, some of which can affect a person’s prognosis. Those listed below are some of the most common, but there are many others. Not all leukemias have these abnormalities. Patients whose AML doesn’t have any of these usually have an outlook that is between favorable and unfavorable.

Favorable abnormalities:

- Translocation between chromosomes 8 and 21 (seen most often in patients with M2)

- Translocation or inversion of chromosome 16

- Translocation between chromosomes 15 and 17 (seen most often in patients with M3)

Unfavorable abnormalities:

- Deletion (loss) of part of chromosome 5 or 7

- Translocation or inversion of chromosome 3

- Translocation between chromosomes 6 and 9

- Translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22

- Abnormalities of chromosome 11 (at the spot q23)

- Loss of a chromosome, so the cell has only 1 copy instead of the normal 2 (known as monosomy)

- Complex changes (those involving 3 or more chromosomes)

Gene mutations

People whose leukemia cells have certain gene mutations may have a better or worse outlook.

For instance, people with AML that has a mutation in the FLT3 gene tend to have a poorer outlook, although new drugs that target cells with this abnormal gene might lead to better outcomes. Mutations in the TP53, RUNX1, and ASXL1 genes are also linked with a worse outlook.

On the other hand, people whose leukemia cells have changes in the NPM1 gene (and no other abnormalities) seem to have a better prognosis than people without this change. Changes in both copies of the CEBPA gene are also linked to a better outcome.

Markers on the leukemia cells

If the leukemia cells have the CD34 protein and/or the P-glycoprotein (MDR1 gene product) on their surface, it is linked to a worse outlook.

Age

Generally, people over 60 don’t do as well as younger people. Some of this may be because they are more likely to have unfavorable chromosome abnormalities. They sometimes also have other medical conditions that can make it harder for them to handle more intense chemotherapy regimens.

White blood cell count

A high white blood cell count (>100,000/mm3) at the time of diagnosis is linked to a worse outlook.

Prior blood disorder leading to acute myelogenous leukemia

Having a prior blood disorder such as a myelodysplastic syndrome is linked to a worse outlook.

AML that develops after a person is treated for another cancer is linked to a worse outlook.

Infection

Having a systemic (blood) infection when you are diagnosed is linked to a worse outlook.

Leukemia cells in the central nervous system

Leukemia that has spread to the area around the brain and spinal cord can be hard to treat, since most chemotherapy drugs can’t reach that area.

Status of acute myelogenous leukemia after treatment

How well (and how quickly) the leukemia responds to treatment also affects long-term prognosis. Better initial responses have been linked with better long-term outcomes.

- A remission (complete remission) is usually defined as having no evidence of disease (NED) after treatment. This means the bone marrow contains fewer than 5% blast cells, the blood cell counts are within normal limits, and there are no signs or symptoms from the leukemia. A complete molecular remission means there is no evidence of leukemia cells in the bone marrow, even when using very sensitive tests, such as PCR (polymerase chain reaction).

- Minimal residual disease (MRD) is a term used after treatment when leukemia cells can’t be found in the bone marrow using standard tests (such as looking at cells under a microscope), but more sensitive tests (such as flow cytometry or PCR) find evidence that there are still leukemia cells in the bone marrow.

- Active disease means that either there is evidence that the leukemia is still present during treatment, or that the disease has come back after treatment (relapsed). For a patient to have relapsed, they must have more than 5% blast cells in their bone marrow.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is an uncommon type of cancer of the blood cells. The term “chronic” in chronic myelogenous leukemia indicates that this cancer tends to progress more slowly than acute forms of leukemia. The term “myelogenous” in chronic myelogenous leukemia refers to the type of cells affected by this cancer. In CML the bone marrow produces too many white cells, called granulocytes. These cells (sometimes called blasts or leukemic blasts) gradually crowd the bone marrow, interfering with normal blood cell production. They also spill out of the bone marrow and circulate around the body in the bloodstream. Because leukemic blasts are not fully mature, they are unable to work properly to fight infections. Over time, a shortage of red cells and platelets can cause anemia, bleeding and/or bruising.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia can also be called chronic myeloid leukemia and chronic granulocytic leukemia. Chronic myelogenous leukemia typically affects older adults and rarely occurs in children, though it can occur at any age.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) can occur at any age but it is more common in adults over the age of 40, who account for nearly 70% of all cases. CML occurs more frequently in men than women and is rarely diagnosed in children.

Most people with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) have a gene mutation (change) called the Philadelphia chromosome. An abnormal chromosome called the Philadelphia chromosome is associated with chronic myelogenous leukemia. The Philadelphia chromosome forms when chromosome 9 and chromosome 22 break and exchange portions (see Figure 1). This creates an abnormally small chromosome 22 and a new combination of instructions for your cells that can lead to the development of chronic myelogenous leukemia.

CML usually develops gradually during the early stages of disease, and progresses slowly over weeks or months. It has three phases:

- Chronic phase

- Accelerated phase

- Blast phase.

Chronic phase

Most people (more than 90%) are diagnosed in the early chronic phase of CML. Blood counts remain relatively stable and the proportion of blast cells in the bone marrow and blood is low (five per cent or less). Most people are generally well at this stage and have few, if any, troubling symptoms of their disease. For most people these days, the duration of this phase is substantially longer than five years, and may exceed 10-15 years.

Accelerated phase

After some time and despite treatment, CML begins to change from a relatively stable disease into a more rapidly progressing one. This is known as the accelerated phase of CML. During this time a proportion of blast cells may start to increase in your bone marrow and circulating blood.

Blast phase

Eventually, CML transforms into a rapidly progressing disease resembling acute leukemia. This is known as the blast phase or blast crisis. It is characterized by a dramatic increase in the number of blast cells in the bone marrow and blood (usually 30% or more) and by the development of more severe symptoms of your disease. In about two-thirds of cases, CML transforms into a disease resembling acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). The remainder transforms into a disease resembling acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Occasionally, the blast cells are said to be undifferentiated or mixed.

Sometimes chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) does not cause any symptoms. If you have symptoms, they may include:

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

- Night sweats

- Fever

- Pain or a feeling of fullness below the ribs on the left side

Tests that examine the blood and bone marrow diagnose chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). Treatments include chemotherapy, stem cell transplants, infusion of donated white blood cells following stem cell transplants, surgery to remove the spleen, and biologic and targeted therapies. Biologic therapy boosts your body’s own ability to fight cancer. Targeted therapy uses substances that attack cancer cells without harming normal cells.

Figure 1. Chronic myelogenous leukemia – Philadelphia chromosome

Chronic myelogenous leukemia causes

Scientists know that CML is not inherited (passed down from one generation to the next) or contagious. Like other types of leukemia, CML is thought to arise from an acquired mutation (or change) in one or more of the genes that normally control the growth and development of blood cells. This change or changes will result in abnormal growth. It’s not clear what initially sets off this process, but doctors have discovered how it progresses into chronic myelogenous leukemia.

Most people diagnosed with CML have a genetic abnormality in their blood cells called the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome. The Philadelphia-chromosome causes the production of an enzyme called tyrosine kinase which leads to CML. Why these mutations occur in the first place remains unknown but there are likely to be a number of factors involved. Research is going on all the time into possible causes of this damage and certain factors have been identified that may put some people at an increased risk. These include exposure to:

- radiation — very high doses of radiation, either accidentally (nuclear accident) or therapeutically (to treat other cancers)

- chemicals — exposure to industrial chemicals like benzene over a long period of time, or exposure to certain types of chemotherapy to treat other cancers.

First, an abnormal chromosome develops

Human cells normally contain 23 pairs of chromosomes. These chromosomes hold the DNA that contains the instructions (genes) that control the cells in your body. In people with chronic myelogenous leukemia, the chromosomes in the blood cells swap sections with each other. A section of chromosome 9 switches places with a section of chromosome 22, creating an extra-short chromosome 22 and an extra-long chromosome 9.

The extra-short chromosome 22 is called the Philadelphia chromosome, named for the city where it was discovered. The Philadelphia chromosome is present in the blood cells of 90 percent of people with chronic myelogenous leukemia.

Second, the abnormal chromosome creates a new gene

The Philadelphia chromosome creates a new gene. Genes from chromosome 9 combine with genes from chromosome 22 to create a new gene called BCR-ABL. The BCR-ABL gene contains instructions that tell the abnormal blood cell to produce too much of a protein called tyrosine kinase. Tyrosine kinase promotes cancer by allowing certain blood cells to grow out of control.

Third, the new gene allows too many diseased blood cells

Your blood cells originate in the bone marrow, a spongy material inside your bones. When your bone marrow functions normally, it produces immature cells (blood stem cells) in a controlled way. These cells then mature and specialize into the various types of blood cells that circulate in your body — red cells, white cells and platelets.

In chronic myelogenous leukemia, this process doesn’t work properly. The tyrosine kinase caused by the BCR-ABL gene causes too many white blood cells. Most or all of these cells contain the abnormal Philadelphia chromosome. The diseased white blood cells don’t grow and die like normal cells. The diseased white blood cells build up in huge numbers, crowding out healthy blood cells and damaging the bone marrow.

Risk factors for chronic myelogenous leukemia

Factors that increase the risk of chronic myelogenous leukemia:

- Older age

- Being male

- Radiation exposure, such as radiation therapy for certain types of cancer

Family history is not a risk factor

The chromosome mutation that leads to chronic myelogenous leukemia isn’t passed from parents to offspring. This mutation is believed to be acquired, meaning it develops after birth.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia symptoms

Chronic myelogenous leukemia doesn’t always reveal itself with obvious signs and symptoms during the early phase. It’s possible to live with chronic myelogenous leukemia for months or years without realizing it and the disease is picked up on a routine blood test.

As chronic myelogenous leukemia progresses, symptoms arise from the increasing number of abnormal blood cells in the bone marrow and blood, and the decreasing number of normal blood cells. Signs and symptoms of chronic myelogenous leukemia are often vague and are more often caused by other things and may include:

- Easy bleeding

- Feeling run-down or tired (fatigue)

- Fever

- Losing weight without trying

- Loss of appetite

- An enlarged spleen (felt as a mass under the left side of the ribcage)

- Feeling full after eating even a small amount of food

- Pale skin

- Sweating excessively during sleep (night sweats)

- Weakness

- Bone pain (caused by leukemia cells spreading from the marrow cavity to the surface of the bone or into the joint)

- Pain or a sense of “fullness” in the belly

But these aren’t just symptoms of CML. They can happen with other cancers, as well as with many conditions that aren’t cancer.

Because people with chronic myelogenous leukemia tend to respond better to treatment when it’s started early, make an appointment with your doctor if you have any persistent signs or symptoms that worry you.

Problems caused by a shortage of blood cells

Many of the signs and symptoms of CML occur because the leukemia cells replace the bone marrow’s normal blood-making cells. As a result, people with CML don’t make enough red blood cells, properly functioning white blood cells, and platelets.

- Anemia is a shortage of red blood cells. It can cause weakness, tiredness, and shortness of breath.

- Leukopenia is a shortage of normal white blood cells. This shortage increases the risk of infections. Although patients with leukemia may have very high white blood cell counts, the leukemia cells don’t protect against infection the way normal white blood cells do.

- Neutropenia means that the level of normal neutrophils is low. Neutrophils, a type of white blood cell, are very important in fighting infection from bacteria. People who are neutropenic have a high risk of getting very serious bacterial infections.

- Thrombocytopenia is a shortage of blood platelets. It can lead to easy bruising or bleeding, with frequent or severe nosebleeds and bleeding gums. Some patients with CML actually have too many platelets (thrombocytosis). But those platelets often don’t work the way they should, so these people often have problems with bleeding and bruising as well.

The most common sign of CML is an abnormal white blood cell count.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia complications

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) can cause a variety of complications, including:

- Fatigue. If diseased white blood cells crowd out healthy red blood cells, anemia may result. Anemia can make you feel tired and worn down. Treatment for CML also can cause a drop in red blood cells.

- Excess bleeding. Blood cells called platelets help control bleeding by plugging small leaks in blood vessels and helping your blood to clot. A shortage of blood platelets (thrombocytopenia) can result in easy bleeding and bruising, including frequent or severe nosebleeds, bleeding from the gums, or tiny red dots caused by bleeding into the skin (petechiae).

- Pain. CML can cause bone pain or joint pain as the bone marrow expands when excess white blood cells build up.

- Enlarged spleen. Some of the extra blood cells produced when you have CML are stored in the spleen. This can cause the spleen to become swollen or enlarged. The swollen spleen takes up space in your abdomen and makes you feel full even after small meals or causes pain on the left side of your body below your ribs.

- Infection. White blood cells help the body fight off infection. Although people with CML have too many white blood cells, these cells are often diseased and don’t function properly. As a result, they aren’t able to fight infection as well as healthy white cells can. In addition, treatment can cause your white cell count to drop too low (neutropenia), also making you vulnerable to infection.

- Death. If CML can’t be successfully treated, it ultimately is fatal.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia diagnosis

Tests and procedures used to diagnose chronic myelogenous leukemia include:

- Physical exam. Your doctor will examine you and check such vital signs as pulse and blood pressure. He or she will also feel your lymph nodes, spleen and abdomen for abnormalities.

- Blood tests. A complete blood count may reveal abnormalities in your blood cells. Blood chemistry tests to measure organ function may also reveal abnormalities that can help your doctor make a diagnosis.

- Bone marrow tests. Bone marrow biopsy and bone marrow aspiration are used to collect bone marrow samples for laboratory testing. These tests involve collecting bone marrow from your hipbone.

- Tests to look for the Philadelphia chromosome. Specialized tests, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, analyze blood or bone marrow samples for the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome or the BCR-ABL gene.

Phases of chronic myelogenous leukemia

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is classified into 3 groups that help predict outlook. Doctors call these groups phases instead of stages. The phase of chronic myelogenous leukemia refers to the aggressiveness of the disease. The phases are based mainly on the number of immature white blood cells (blasts) in the blood or bone marrow. Different groups of experts have suggested slightly different cutoffs to define the phases, but a common system (proposed by the World Health Organization) is described below. Not all doctors may agree with or follow these cutoff points for the different phases. If you have questions about what phase your CML is in, be sure to have your doctor explain it to you in a way that you understand.

Phases of chronic myelogenous leukemia include:

- Chronic. The chronic phase is the earliest phase and generally has the best response to treatment.

- Accelerated. The accelerated phase is a transitional phase when the disease becomes more aggressive.

- Blastic. Blastic phase is a severe, aggressive phase that becomes life-threatening.

Chronic phase

Patients in the chronic phase typically have less than 10% blasts in their blood or bone marrow samples. These patients usually have fairly mild symptoms (if any) and usually respond to standard treatments. Most patients are diagnosed in the chronic phase.

Accelerated phase

Patients are considered to be in accelerated phase if any of the following are true:

- The blood samples have 15% or more, but fewer than 30% blasts

- Basophils make up 20% or more of the blood

- Blasts and promyelocytes combined make up 30% or more of the blood

- Very low platelet counts (100 x 1,000/mm3 or less) that are not caused by treatment

- New chromosome changes in the leukemia cells with the Philadelphia chromosome

Patients whose CML is in an accelerated phase may have symptoms such as fever, poor appetite, and weight loss. CML in the accelerated phase doesn’t respond as well to treatment as CML in the chronic phase.

Blast phase (acute phase or blast crisis)

Blast phase (also called acute phase or blast crisis), the bone marrow and/or blood samples from a patient in this phase have 20% or more blasts. Large clusters of blasts are seen in the bone marrow. The blast cells have spread to tissues and organs beyond the bone marrow. These patients often have fever, poor appetite, and weight loss. In this phase, the CML acts a lot like an acute leukemia.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia treatment

The treatment chosen for your CML largely depends on the phase of your disease, your age and general health. The goal of chronic myelogenous leukemia treatment is to eliminate the blood cells that contain the abnormal BCR-ABL gene that causes the overabundance of diseased blood cells. For most people, it’s not possible to eliminate all diseased cells, but treatment can help achieve a long-term remission of the disease.

Most people with CML will be treated with drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Tyrosine kinase inhibitors work by blocking the activity of an enzyme called BCR-ABL and thereby preventing the growth and proliferation of the leukemic cells. The most common decision to be made at diagnosis is which of the three available tyrosine kinase inhibitor drugs is most suited to you. This varies from person to person and your doctor will examine all the information about you that is available to them to decide on the most suitable option.

While these drugs are very effective at controlling the disease, most people are required to take these medications for life to keep the disease under control. Only a minority of patients may be ‘cured’ by tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy and are able to safely stop taking them. People with well-controlled CML are expected to have a normal life expectancy.

In a very small number of patients, a stem cell transplant from a matched donor may be considered. This is only considered in patients who do not respond well to tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy and have progressive CML. This treatment, although offering the prospect of a cure, carries serious risks.

Chronic phase

While you are in the chronic phase of CML, treatment is aimed at controlling your disease, prolonging this phase and delaying the onset of symptoms and complications for as long as possible. When you are first diagnosed with CML it can take one to two weeks to start therapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Patients with an elevated white cell count at diagnosis may be given a short course of chemotherapy tablets called hydroxyurea to reduce the CML count. Most people tolerate hydroxyurea well.

Adherence, also commonly called compliance, to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors for CML is very important for the drugs to work effectively. If there is not enough drug in the body (due to skipped doses), it is possible that the CML cells may become resistant via a process called mutation. Some mutations do not respond well to tyrosine kinase inhibitors, therefore it is very important to take your medication as directed and do not make any changes without discussing it first with your haematologist.

Advanced phase

Although uncommon, some people already have advanced disease at diagnosis, while others may experience disease progression. Advanced phase treatment is aimed at re-establishing the chronic phase of CML and reducing any troublesome symptoms. There are several treatment options that may be used. The treatment of accelerated and blast phase CML usually involves a more intensive approach. These include more intensive chemotherapy using a combination of drugs similar to those used to treat acute leukaemia in combination with a different tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

A stem cell transplant is now generally only used for people in whom the CML has not responded to tyrosine kinase inhibitors, or who were diagnosed in the accelerated phase. Some patients may benefit by participating in a clinical trial.

Targeted drugs

Targeted drugs are designed to attack cancer by focusing on a specific aspect of cancer cells that allows them to grow and multiply. In chronic myelogenous leukemia, the target of these drugs is the protein produced by the BCR-ABL gene — tyrosine kinase. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor drugs that block the action of tyrosine kinase include:

- Imatinib (Gleevec)

- Dasatinib (Sprycel)

- Nilotinib (Tasigna)

- Bosutinib (Bosulif)

- Ponatinib (Iclusig)

Targeted drugs are the initial treatment for most people diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia. If the disease doesn’t respond or becomes resistant to the first targeted drug, doctors may consider other targeted drugs, such as omacetaxine (Synribo), or other treatments. Side effects of these targeted drugs include swelling or puffiness of the skin, nausea, muscle cramps, rash, fatigue, diarrhea, and skin rashes.

Doctors haven’t determined a safe point at which people with chronic myelogenous leukemia can stop taking targeted drugs. For this reason, most people continue to take targeted drugs even when blood tests reveal a remission of chronic myelogenous leukemia.

Blood stem cell transplant

A blood stem cell transplant, also called a bone marrow transplant, offers the only chance for a definitive cure for chronic myelogenous leukemia. However, it’s usually reserved for people who haven’t been helped by other treatments because blood stem cell transplants have risks and carry a high rate of serious complications.

During a blood stem cell transplant, high doses of chemotherapy drugs are used to kill the blood-forming cells in your bone marrow. Then blood stem cells from a donor or your own cells that were previously collected and stored are infused into your bloodstream. The new cells form new, healthy blood cells to replace the diseased cells.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy drugs are typically combined with other treatments for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Often, chemotherapy treatment for chronic myelogenous leukemia is given as a tablet you take by mouth. Side effects of chemotherapy drugs depend on what drugs you take.

Biological therapy

Biological therapies harness your body’s immune system to help fight cancer. The biological drug interferon is a synthetic version of an immune system cell. Interferon may help reduce the growth of leukemia cells. Interferon may be an option if other treatments don’t work or if you can’t take other drugs, such as during pregnancy. Side effects of interferon include fatigue, fever, flu-like symptoms and weight loss.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials study the latest treatment for diseases or new ways of using existing treatments. Enrolling in a clinical trial for chronic myelogenous leukemia may give you the chance to try the latest treatment, but it can’t guarantee a cure. Talk to your doctor about what clinical trials are available to you. Together you can discuss the benefits and risks of a clinical trial.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia prognosis

For many people, chronic myelogenous leukemia is a disease they will live with for years. Many will continue treatment with imatinib (Gleevec®) indefinitely. Some days, you may feel sick even if you don’t look sick.

Drugs that are highly effective in treating most cases of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) first became available in 2001. There’s no accurate information yet on how long patients treated with these drugs may live. All that’s known is that most patients who have been treated with these drugs, starting in 2001 (or even before), are still alive.

One large study of CML patients treated with imatinib (Gleevec®) found that about 90% of them were still alive 5 years after starting treatment. Most of these patients had normal white blood cells and chromosome studies after 5 years on the drug.

Prognostic factors for chronic myeloid leukemia

Along with the phase of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), there are other factors that may help predict the outlook for survival. These factors are sometimes helpful when choosing treatment. Factors that tend to be linked with shorter survival time are called adverse prognostic factors.

Adverse prognostic factors:

- Accelerated phase or blast phase

- Enlarged spleen

- Areas of bone damage from growth of leukemia

- Increased number of basophils and eosinophils (certain types of granulocytes) in blood samples

- Very high or very low platelet counts

- Age 60 years or older

- Multiple chromosome changes in the CML cells

Many of these factors are taken into account in the Sokal system, which develops a score used to help predict prognosis. This system considers the person’s age, the percentage of blasts in the blood, the size of the spleen, and the number of platelets. These factors are used to divide patients into low-, intermediate-, or high-risk groups. Another system, called the Euro score, includes the above factors, as well as the percentage of blood basophils and eosinophils. Having more of these cells indicates a poorer outlook.

The Sokal and Euro models were helpful in the past, before the newer, more effective drugs for CML were developed. It’s not clear how helpful they are at this time in predicting a person’s outlook. Targeted therapy drugs like imatinib (Gleevec®) have changed the treatment of CML dramatically. These models haven’t been tested in people who are being treated with these drugs.