What is nose bleeds

A nosebleed also called epistaxis, is loss of blood from the tissue lining your nose. Bleeding most often occurs in one nostril only. Nosebleeds are very common. Most nosebleeds occur because of minor irritations, after an injury or colds. Most nosebleeds are mild and do not last long. Nose bleeds are common in children and older people with medical conditions.

Although nose bleeds can be scary, they’re generally only a minor annoyance and aren’t dangerous. Frequent nosebleeds are those that occur more than once a week.

In the United States, one of every seven people will develop a nosebleed some time in their lifetime. Nosebleeds can occur at any age but are most common in children aged 2-10 years and adults aged 50-80 years.

Older people and people with medical conditions, such as blood disorders or those taking blood-thinning medicines, can also be more likely to experience nosebleeds. In these cases the bleeding can be severe and medical assistance may be needed to stop the bleeding.

Nose bleeds can often occur if you:

- Have allergies, infections, or dryness that cause itching and lead to picking of the nose.

- Pick your nose

- Blow your nose too hard that ruptures superficial blood vessels

- Strain too hard on the toilet

- Have an infection in the nose, throat or sinuses

- Low humidity or irritating fumes: If your house is very dry, or if you live in a dry climate, the lining of your child’s nose may dry out, making it more likely to bleed. If he is frequently exposed to toxic fumes (fortunately, an unusual occurrence), they may cause nosebleeds, too.

- Receive a bump, knock or blow to the head or face

- Have a cold

- Have a bunged-up or stuffy nose from an allergy.

- Anatomical problems: Any abnormal structure inside the nose can lead to crusting and bleeding (e.g., deviated septum)

- Are taking some types of medicines, such as anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin) or anti-inflammatories (e.g., aspirin) or nose sprays

- Clotting disorders that run in families or are due to medications.

- Fractures of the nose or the base of the skull. Head injuries that cause nosebleeds should be regarded seriously.

- Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, a disorder involving a blood vessel growth similar to a birthmark in the back of the nose.

- Tumors, both malignant and nonmalignant, have to be considered, particularly in the older patient or in smokers.

In general, nose bleeds are not a symptom or result of high blood pressure. It is possible, but rare, that severe high blood pressure may worsen or prolong bleeding if you have a nosebleed.

How do I stop a nosebleed?

- Stay calm, or help a young child stay calm. A person who is agitated may bleed more profusely than someone whos been reassured and supported.

- Keep head higher than the level of the heart. Sit up.

- Sit down and lean slightly forward so the blood wont drain in the back of the throat.

- Gently blow any clotted blood out of the nose.

- Using the thumb and index finger, pinch all the soft parts of the nose. Do not pack the inside of the nose with gauze or cotton.

- Hold the position for five to ten minutes. If its still bleeding, hold it again for an additional 10 to 15 minutes.

Once the bleeding has stopped, encourage your child not to blow or pick his nose for about 24 hours. This will help the blood clot in his nose to strengthen.

Your child might vomit during or after a nosebleed if she has swallowed some blood. This is pretty normal, and your child should spit out the blood.

When the bleeding won’t stop

If you can’t stop the bleeding with the treatment steps above, you should take your child to the doctor or hospital emergency department.

The doctor might put some cream or ointment up your child’s nose to help stop the bleeding.

Another treatment can involve nose-packing. This is where the doctor puts a special cloth dressing into your child’s nose. Your child will need a follow-up appointment 24-48 hours later to have the dressing taken out.

Cautery is another common treatment. This is where a special chemical is used to seal off the bleeding and ‘freeze’ the blood vessel. Doctors usually use anaesthetic for cautery.

Very rarely your child might need to see an ear, nose and throat specialist and go into hospital for treatment.

After a bleeding nose

Here’s what to do after your child has had a bleeding nose:

- Ensure your child rests over the next 24 hours.

- Keep your child out of hot baths.

- Encourage your child not to pick or blow her nose.

Sometimes a doctor will recommend that your child uses a saline nasal spray or lubricating ointment to help with dryness. The doctor might also recommend using an antibiotic ointment, which you’ll need to put up your child’s nose.

Most nosebleeds aren’t serious and will stop on their own or by following self-care steps.

Seek emergency medical care if nosebleeds:

- Follow an injury, such as a car accident

- Nose bleeding occurs after a head injury. This may suggest a skull fracture, and x-rays should be taken.

- Your nose may be broken (for example, it looks crooked after a hit to the nose or other injury).

- Involve a greater than expected amount of blood.

- Interfere with breathing.

- Last longer than 20 to 30 minutes even with compression.

- Occur in children younger than age 2.

- Your child is generally unwell, looks pale or has unexplained bruises on her body.

- Your child has regular nosebleeds.

Don’t drive yourself to an emergency room if you’re losing a lot of blood. Call your local emergency services number or have someone drive you.

See your doctor if you’re having frequent nosebleeds, even if you can stop them fairly easily. It’s important to determine the cause of frequent nosebleeds.

An ear, nose, and throat specialist (otolaryngologist) will carefully examine the nose using an endoscope, a tube with a light for seeing inside the nose, prior to making a treatment recommendation. Two of the most common treatments are cautery and packing the nose. Cautery is a technique in which the blood vessel is burned with an electric current, silver nitrate, or a laser. Sometimes, a doctor may just pack the nose with a special gauze or an inflatable latex balloon to put pressure on the blood vessel.

Why do people get nose bleeds

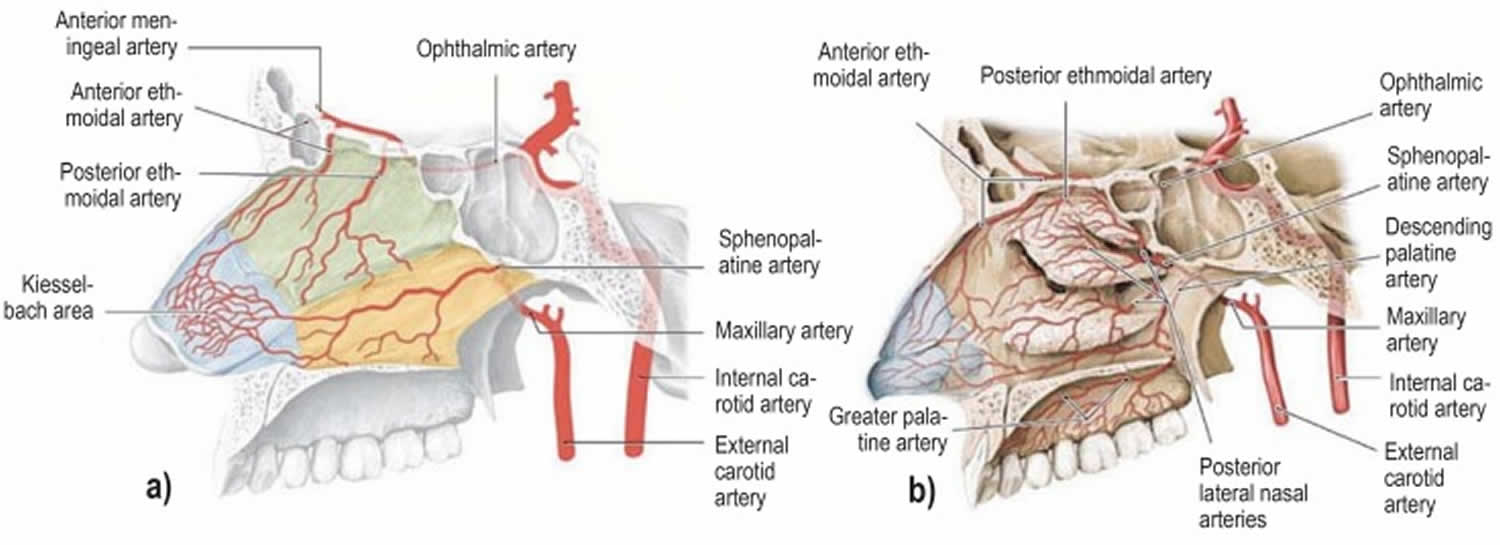

The nose is an area of the body that contains many tiny blood vessels (or arterioles) that can break and bleed easily (see Figure 1). Air moving through the nose can dry and irritate the membranes lining the inside of the nose. Crusts can form that bleed when irritated. Nosebleeds occur more often in the winter, when cold viruses are common and indoor air tends to be drier.

Nosebleeds are divided into two types, depending on whether the bleeding is coming from the front or back of the nose.

Most nosebleeds occur on the front of the nasal septum (anterior nosebleed). This is the piece of the tissue that separates the two sides of the nose. This type of nosebleed can be easy for a trained professional to stop. Less commonly, nosebleeds may occur higher on the septum or deeper in the nose such as in the sinuses or the base of the skull. Such nosebleeds may be harder to control. However, nosebleeds are rarely life threatening.

In 90% to 95% of cases of nose bleeds (epistaxis), the source of the bleed is in the area on the front part of the nasal septum (anterior nosebleed), the Kiesselbach area (Little’s area) 1 and in 5% to 10% of cases it occurs posteriorly in the posterior region of the nasal cavity 2.

Figure 1. Arteries involve in nose bleeds (nasal septum)

Figure 2. Arterial supply of the nasal cavity

Footnote: The different territories supplied by the internal carotid artery (green) and the external carotid artery (yellow) are indicated in a). The Kiesselbach area (blue) is supplied by branches of both the main arteries (red).

a) Arteries supplying the nasal septum and b) the lateral walls of the nasal cavity.

[Source 1 ]Figure 3. Nose cartilage (nasal septum)

What is an anterior nosebleed?

Most nosebleeds (or epistaxes) begin in the lower part of the septum, the semi-rigid wall that separates the two nostrils of the nose. The septum contains blood vessels that can be broken by a blow to the nose or the edge of a sharp fingernail. Nosebleeds coming from the front of the nose, (anterior nosebleeds) often begin with a flow of blood out one nostril when the patient is sitting or standing.

Anterior nosebleeds are common in dry climates or during the winter months when dry, heated indoor air dehydrates the nasal membranes. Dryness may result in crusting, cracking, and bleeding. This can be prevented by placing a light coating of petroleum jelly or an antibiotic ointment on the end of a fingertip and then rubbing it inside the nose, especially on the middle portion of the nose (the septum).

What is a posterior nosebleed?

More rarely, a nosebleed can begin high and deep within the nose and flow down the back of the mouth and throat, even if the patient is sitting or standing.

Obviously, when lying down, even anterior (front of nasal cavity) nosebleeds may seem to flow toward the back of the throat, especially if coughing or blowing the nose. It is important to try to make the distinction between the anterior and posterior nosebleed, since posterior nosebleeds are often more severe and almost always require a physicians care. Posterior nosebleeds are more likely to occur in older people, persons with high blood pressure, and in cases of injury to the nose or face.

Recurring nosebleeds

Recurring nosebleeds can be a nuisance, but are usually nothing to worry about. However, you should discuss it with your doctor as they may want to investigate that there is no underlying medical condition which is causing the bleeds.

If your nosebleeds persist and become a problem, you may need treatment, such as surgery to cauterize (burn) the blood vessels in the nose. Talk to your doctor about your options.

What to expect at your doctor

Your doctor will perform a physical exam. In some cases, you may be watched for signs and symptoms of low blood pressure from losing blood, also called hypovolemic shock.

You may have the following tests:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Nasal endoscopy (examination of the nose using a camera)

- Partial thromboplastin time measurements

- Prothrombin time (PT)

- CT scan of the nose and sinuses

The type of treatment used will be based on the cause of the nosebleed. Treatment may include:

- Controlling blood pressure

- Closing the blood vessel using heat, electric current, or silver nitrate sticks

- Nasal packing

- Reducing a broken nose or removing a foreign body

- Reducing the amount of blood thinner medicine or stopping aspirin

- Treating problems that keeps your blood from clotting normally

You may need to see an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist for further tests and treatment.

How to stop nose bleeds

To stop a nosebleed:

- Sit upright and lean forward. By remaining upright, you reduce blood pressure in the veins of your nose. This discourages further bleeding. Sitting forward will help you avoid swallowing blood, which can irritate your stomach.

- Gently blow your nose to clear out any clotted blood.

- Pinch your nose. Use your thumb and index finger to pinch both nostrils shut, even if only one side is bleeding. Breathe through your mouth. Continue to pinch for 10 to 15 minutes by the clock. This maneuver puts pressure on the bleeding point on the nasal septum and often stops the flow of blood. If the bleeding is coming from higher up, the doctor may need to apply packing up into your nose if it doesn’t stop on its own.

- Wait at least 10 to 15 minutes before checking if the bleeding has stopped. Be sure to allow enough time for the bleeding to stop.

- Repeat. If the bleeding doesn’t stop, repeat these steps for up to a total of 15 minutes.

After the bleeding has stopped, to keep it from starting again, don’t pick or blow your nose and don’t bend down for several hours. Keep your head higher than the level of your heart.

It may help to apply cold compresses or ice across the bridge of the nose. Do not pack the inside of the nose with gauze.

Lying down with a nosebleed is not recommended. You should avoid sniffing or blowing your nose for several hours after a nosebleed. If bleeding persists, a nasal spray decongestant (Afrin, Neo-Synephrine) can sometimes be used to close off small vessels and control bleeding.

Things you can do to prevent frequent nosebleeds include:

- Keep the home cool and use a vaporizer/humidifier to add moisture to the inside air. A humidifier will counteract the effects of dry air by adding moisture to the air.

- Use nasal saline spray and water-soluble jelly (such as Ayr gel) to prevent nasal linings from drying out in the winter.

- Keeping the lining of the nose moist. Especially during colder months when air is dry, apply a thin, light coating of petroleum jelly (Vaseline) or antibiotic ointment (bacitracin, Neosporin) with a cotton swab three times a day. Saline nasal spray also can help moisten dry nasal membranes.

- Trimming your child’s fingernails. Keeping fingernails short helps discourage nose picking.

Tips to prevent a nosebleed

- Keep the lining of the nose moist by gently applying a light coating of petroleum jelly or an antibiotic ointment with a cotton swab three times daily, including at bedtime. Commonly used products include Bacitracin, A and D Ointment, Eucerin, Polysporin, and Vaseline.

- Keep childrens fingernails short to discourage nose-picking.

- Counteract the effects of dry air by using a humidifier.

- Use a saline nasal spray to moisten dry nasal membranes.

- Quit smoking. Smoking dries out the nose and irritates it.

To prevent recurrences, care of the nasal mucosa using an antiseptic nasal cream is recommended. A prospective, randomized, controlled study in the United Kingdom in children with recurrent epistaxis compared treatment with an antiseptic cream for 4 weeks versus a wait-and-see policy 1. A significantly lower recurrence rate was seen in the treatment group (45% versus 71% recurrence rate) 3. In addition, energetic nose blowing should be avoided for 7 to 10 days 4. Bed rest is not necessary. According to a Danish prospective, randomized study, mobilizing the patient does not increase recurrence in comparison to bed rest 5.

Tips to prevent rebleeding after initial bleeding has stopped

- Do not pick or blow nose.

- Do not strain or bend down to lift anything heavy.

- Keep head higher than the heart.

If rebleeding occurs

- Attempt to clear nose of all blood clots.

- Spray nose four times in the bleeding nostril(s) with a decongestant spray.

- Repeat the steps to stop an anterior nosebleed.

- See a doctor if bleeding persists after 30 minutes or if nosebleed occurs after an injury to the head.

Nosebleeds in children

A child with a nosebleed may be very frightened or distressed about it. Try to comfort and reassure your children that nosebleeds are very common and lots of other kids get them. It doesn’t mean they are ill, and they will get better very soon.

Some toddlers and young children like to put small foreign objects into their ears or noses, or swallow things that aren’t food, out of curiosity. They’re experimenting with the world around them and learning what happens when they try different things.

If an item becomes stuck in your child’s nose, you should not try to remove the object yourself. You should take the child to your nearest doctor or emergency department for further treatment.

Pushing an object, especially a sharp one, up the nose, can cause damage that leads to bleeding from the nose.

If the object falls back into the throat and your child can start to choke, call your local emergency services number for an ambulance. If the object contains chemicals (like a battery) or is a bean (which can swell) you should go to the Emergency Department.

Signs your child has a foreign object stuck in his/her nose

Your child might:

- complain of pain or itchiness

- have a smelly discharge from one nostril

- bleed from the nose

- have bad breath.

Foreign objects to look out for

Children under four years are most at risk of inserting or swallowing small foreign objects, so keep the following out of reach of your child:

- foods such as popcorn, dried peas, watermelon seeds, nuts and chocolate with nuts

- marbles, buttons, beads and pen lids

- polystyrene balls found in bean bags and stuffed toys − these can be inhaled and don’t show up on x-rays

- coins

- small batteries, which can leak acid and cause injury if swallowed

- toys with removable eyes, noses or other small parts

- needles, pins and safety pins.

It’s best to use pins with a safety catch, and keep them closed when you’re not using them. Also avoid putting safety pins in your mouth, because your child might copy you.

Preventing foreign objects from being swallowed, inhaled or inserted

It’s important to try to identify potentially risky situations ahead of time. These tips can help:

- Supervise toddlers and small children while they eat − they like to experiment and play with food, which can lead to injuries. Encourage your child to sit quietly when eating and drinking.

- Don’t give your child popcorn or nuts (especially peanuts) until he’s at least three years old. A thin layer of peanut butter or hazelnut spread on bread is a good alternative.

- Cut all food into small pieces, and remove sharp or small bones from fish, chicken and meat before giving them to your child. Preboned fillets can be a good option.

- Try to wait until your child is four years old before letting her eat small lollies. Lollies are sometimes food and best saved for special occasions anyway.

- Avoid glitter, glue and small beadwork.

- Teach older siblings that a baby’s ears and nose are delicate, and that they’re not for poking things into.

- It’s best to sand or polish any rough, splintery timber your child might come into contact with – for example, on old furniture or veranda rails.

- Check the floor and low tables for pieces of jewellery, dried peas and other small objects.

What can cause nose bleeds

The two most common causes of nosebleeds are:

- Dry air — when your nasal membranes dry out, they’re more susceptible to bleeding and infections

- Nose picking

Other causes of nose bleeds include:

- Acute sinusitis (sinus infection)

- Allergies

- Aspirin use

- Bleeding disorders, such as hemophilia

- Blood thinners (anticoagulants), such as warfarin and heparin

- Blowing the nose very hard, or picking the nose

- Chemical irritants, such as ammonia, including medicines or drugs that are sprayed or snorted

- Chronic sinusitis

- Cocaine use

- Common cold

- Deviated septum

- Foreign body in the nose

- Irritation due to allergies, colds, sneezing or sinus problems

- Nasal sprays, such as those used to treat allergies, if used frequently

- Nonallergic rhinitis (chronic congestion or sneezing not related to allergies)

- Overuse of decongestant nasal sprays

- Oxygen treatment through nasal cannulas

- Trauma to the nose, including a broken nose, or an object stuck in the nose

- Very cold or dry air

Medical drugs associated with nosebleeds 1:

- Phenprocoumon

- Dabigatran

- Rivaroxiban

- Fondaparinux

- Clopidogrel

- Acetylsalicylic acid

- Glucocorticoid nasal sprays

- Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors

Less common causes of nosebleeds include:

- Alcohol use

- Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)

- Leukemia

- Nasal and paranasal tumors

- Nasal polyps

- Nasal surgery

- Pregnancy

- Sinus or pituitary surgery (transsphenoidal)

Repeated nosebleeds may be a symptom of another disease such as high blood pressure, a bleeding disorder, or a tumor of the nose or sinuses. Blood thinners, such as warfarin (Coumadin), clopidogrel (Plavix), or aspirin, may cause or worsen nosebleeds.

Nose bleeds treatment

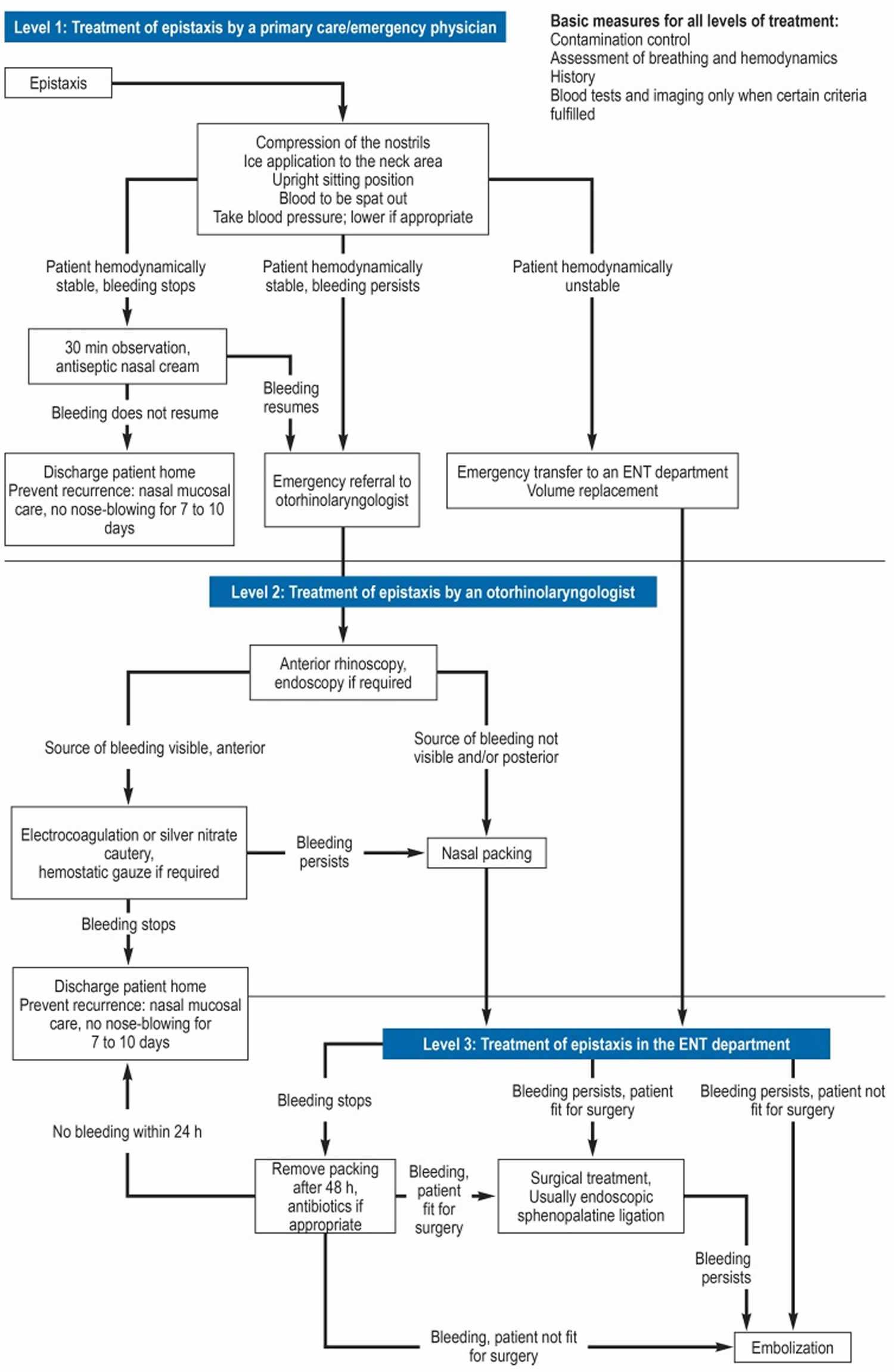

No uniform guidelines exist for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in patients with nosebleeds (epistaxis) 1. However, clinically tried and tested treatment paths do emerge in hospitals and doctors’ offices, based largely on retrospective analyses, case series, and expert opinion. Only few prospective or randomized controlled studies are available for some discrete areas of epistaxis treatment.

Figure 5 shows the treatment algorithm developed by experts, which includes treatment recommendations from the international literature as well as their department’s own in-house standard operating procedures.

Figure 5. Nose bleed treatment algorithm

[Source 1 ]Initial assessment of breathing and hemodynamics

Especially in cases of severe bleeding, following the ABC approach, security of the airway, breathing, and cardiovascular stability should be assessed 4. If symptoms of hypovolemia are found, a peripheral venous access should be placed and volume replacement therapy started. Early blood pressure measurement is an essential part of the diagnostic process.

History taking

The most important parts of the history are first of all the intensity and course over time of the bleed, which allow a judgment to be made about the urgency of treatment 4. The patient should be asked about factors that would predispose to epistaxis 6. An important element of the history is what medication the patient is on, especially any anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs 4.

Blood tests

In many cases of uncomplicated nosebleeds, no blood tests are required. If the patient is on anticoagulation therapy, however, coagulation testing with International Normalized Ratio (INR) measurement should be carried out.

Imaging

Imaging is not usually necessary. However, in patients with recurrent nose bleeds of unknown cause, imaging should be carried out to investigate the possibility of neoplastic disease such as juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma 7.

Management of patients on anticoagulants

In France, guidelines on the management of nose bleeds in patients taking anticoagulants have existed since 2016 8. In acute nose bleeds, these recommend screening for overdose and assessment of the risk of thrombosis. Anticoagulation therapy should always be continued so long as the bleeding can be stopped or controlled. Only if bleeding is massive and unstoppable, or if an anticoagulation overdose is found, should adjustment of the anticoagulation therapy be considered in consultation with a hematologist and cardiologist.

If the nose bleed can be stopped or controlled, anticoagulation therapy should be continued. Only if nose bleed is massive and unstoppable, e.g., due to anticoagulation overdose, should adjustment of the anticoagulation therapy be considered.

Antiplatelet drugs

Because it takes up to 10 days for hemostasis to be restored after cessation of antiplatelet therapy, stopping antiplatelet drugs in a patient with acute nose bleed is not useful. If the bleeding cannot be halted, stopping antiplatelet therapy while at the same time giving platelet transfusions is an option 8.

Vitamin K antagonists

For a patients taking a vitamin K antagonist, the drug should be stopped and an antidote given only if the bleeding is uncontrollable. If the vitamin K antagonist has been overdosed and the bleeding can be controlled, the dosage should be altered 8.

Direct oral anticoagulants

Stopping medication with direct oral anticoagulants is recommended only after consultation with a cardiologist. If bleeding is uncontrolled, dabigatran is the only drug for which an antidote (idarucizumab 5 mg in two consecutive 5– to 10-min intravenous infusions) is currently available 8.

Anticoagulation treatment should not be altered in a patient about to undergo endovascular embolization (expert opinion) 8.

Treatment by the primary care physician and/or emergency physician

The first step is to compress both sides of the nose continuously for 15 to 20 min, using two fingers or a nose clip 9. The patient should sit upright and lean slightly forward to prevent the blood from running down the pharynx 6. Local application of ice, e.g., at the back of the neck, is intended to encourage vasoconstriction of the blood vessels of the nose. Its therapeutic value is a matter of debate and has been challenged in the literature 10. No final conclusion can be drawn on the basis of existing publications. In patients with raised blood pressure that is not causing symptoms (>180/120 mmHg, measured several times), the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology recommend oral medication to reduce the blood pressure. The aim is to slowly reduce the blood pressure over a period of 24 to 48 hours 11. In around 65% to 75% of cases, these steps combined with application of a decongestant, oxymetazoline-based nasal spray will succeed in stopping the bleeding 12. If bleeding does not restart during a 30-minute observation period and the patient is hemodynamically stable, emergency specialist ENT treatment is not required.

In the presence of any of the following, experts recommend consultation with an otorhinolaryngologist (ENT specialist):

- Epistaxis uncontrollable by the measures described above

- Recurrent nose bleed

- Suspected neoplasm as the source of the bleed

Treatment by a ENT specialist (otorhinolaryngologist)

Anterior rhinoscopy

To locate the source of the bleeding, the first investigation is anterior rhinoscopy with a nasal speculum and headlight 4. Once any clots have been removed by suction or with pincers, the nasal cavity can be inspected, including the Kiesselbach area, where the bleeding often originates. Application of a vasoconstrictor and local anesthetic, e.g., in the form of an impregnated cotton tuft, will enable a better view. Owing to the local anesthetic effect, this step has therapeutic as well as diagnostic value 9.

Endoscopy

Especially in cases where the bleeding is from the posterior nasal cavity, locating the source of the bleeding by anterior rhinoscopy is difficult. In such cases, the French guidelines on treating nose bleed recommend as a supplementary procedure rigid endoscopy of the nasal cavity by a physician experienced in endoscopy 9. Two prospective studies have shown that 80% to 94% of bleed sources can be identified by endoscopy 13.

Nose cauterization

Most cases of nose bleed from an easily visible anterior source can be effectively treated by cauterization with silver nitrate or electrocoagulation. Before starting the procedure, a vasoconstrictor and local anesthetic should be applied 14. A Swiss retrospective study showed that in terms of therapeutic success, electrocoagulation was superior to chemical coagulation (88% versus 78%) (failure rate 12% versus 22%) 15. A US study of children treated intraoperatively by these same two methods for recurrent anterior nose bleed also found a lower recurrence rate for electrocoagulation than for chemical cauterization during the 2-year period after the procedure (recurrence events 2% versus 18%) 16. Chemical cautery is described as simpler to use, cheaper, and more widely available 17. Complications of nose cauterization include septal perforation, infection, rhinorrhea, and increased bleeding 6. Bilateral cautery in the area of the nasal septum should be avoided if possible, as this risks septal perforation 18. There are no published studies on the incidence of septal perforation after cautery 19.

Hemostatic gauze

As a supplement to cautery, local application of gauze made of oxidized regenerated cellulose can be used. As a resorbable hemostyptic, it supports physiological hemostasis. Diffuse mucosal bleedings in particular can often be adequately managed by the application of a thin layer of this gauze 20.

Nasal packing

If nasal cauterization is unsuccessful, the next step in managing nose bleed is nasal packing. Packing takes different forms for anterior and posterior bleeding. Bilateral nasal packing produces a higher intranasal pressure than unilateral packing and its practice is therefore widespread, although there is little evidence to support this 21.

Overview of the most commonly used nasal packing materials

- Rubber-coated sponge tampons: Rubber-coated sponge tampons are sponges covered with a layer of rubber that prevents colonization by bacteria or viruses. Effective for hemostasis, simple and relatively atraumatic to apply and remove, and causing little discomfort for the patient, rubber-coated sponge packs are the norm for nasal packing in Germany. Complications to watch out for include damage from pressure to the columella and nasal cartilage, and posterior dislocation 22.

- Expandable nasal packs: Expandable nasal packs are usually made of polyvinyl acetal and expand on contact with blood or water. The advantage of this form of pack is that, especially when made of materials with small pores, placement and removal are comparatively less traumatic and unpleasant for the patient. Rapid Rhino is a special form of this kind of pack. A Rapid Rhino pack consists of a core sponge or balloon covered in a carboxymethyl cellulose fabric intended to promote aggregation of thrombocytes 22.

- Cotton ribbon gauze: Pledgets of cotton ribbon gauze are placed intranasally for ongoing packing, usually after impregnation with Vaseline or an antibiotic cream. The advantage is that it is easy to place the gauze exactly where it is wanted for local pressure effect 23. Disadvantages are that placing and removing the pledgets is relatively painful for the patient, they are less comfortable when in place, bleeding can be caused when they are removed, and paraffinomas may form where they are placed 23.

- Balloon packing: The main indication for balloon packing is severe posterior bleeding 22. Additional anterior packing is always required. Once the nasopharyngeal balloon has been advanced along the caudal part of the main nasal cavity, it should be filled with up to 10 mL sterile water for injection purposes and then carefully pulled against the choanae 4. If a nasopharyngeal balloon is not available, use of a Foley catheter, which is expanded in the nasopharynx, has been described as a possible alternative 6. Double balloon catheters also exist which, in addition to the posterior balloon for the nasopharynx, also have an anterior balloon that is inflated in the nasal cavity. Because of the relatively high risk of pressure necrosis, balloon packing of the nasal cavity should be used with caution 22.

- Bellocq posterior nasal pack: The principle of the Bellocq posterior nasal pack is based on sealing off the nasopharynx with a gauze or sponge pack which is pulled into the nasopharynx via the mouth by means of two transnasally introduced rubber catheters. This is is very uncomfortable for the patient, who should therefore preferably be sedated or under general anesthesia while it is being carried out. Moreover, this method of packing has a markedly higher rate of associated local and general complications than does the nasopharyngeal balloon 24. Its use is therefore only indicated in patients with posterior nose bleed where anterior packing and balloon catheters fail and in those with nasopharyngeal bleeding, e.g., after cancer surgery 25.

Complications of nasal packing

The most serious complication of nasal packing is posterior dislocation. Reports have been published of fatal aspiration of nasal packs 26. Rubber-coated sponge tampons and cotton ribbon gauze packs are liable to dislocate 22. To prevent this, all nasal packs must be strongly fixed to the patient’s face, e.g., with sticking plaster on the bridge of the nose or the cheek 27. Additionally, the threads attached to some packs should be tied together in front of the columella. Other reported complications include allergic reaction, mucosal necrosis, foreign body reaction, tube dysfunction, paraffinoma, and decompensation of pre-existing sleep apnea 27. Nasal packing can also cause discomfort for the patient in the form of pain, obstructed breathing, and a reduced sense of smell 22. In addition, bilateral nasal packing can result in impaired pressure equalization via the auditory (Eustachian) tube, leading to the patient’s discomfort due to negative pressure in the middle ear 22. There have been case reports of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome as a serious complication 28. The release of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST1) causes symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, fever, myalgia, diffuse erythema, and even septic shock. Treatment consists of immediate removal of the packing, intravenous antibiotics, and transfer of the patient to an intensive care ward 22.

Prophylactic antibiotics

The role of prophylactic administration of antibiotics with nasal packing has not been adequately studied. Wide variation in practice has been described in England 29, e.g., prophylactic antibiotics in patients with cardiac anomalies, especially prosthetic heart valves 14. Like some other authors, with anterior nasal packing we recommend prophylactic antibiotics only after the packing has been in place for more than 48 hours, but with posterior packing we recommend it in all cases, with the aim of preventing migration of infection into the sinuses and middle ear and toxic shock syndrome 25. Preferred antibiotics are amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, amoxicillin alone, and cephalosporins 29.

Removal of nasal packing

When to remove the nasal packing is variously defined in the literature, ranging from 12 or 24 hours to 3 to 5 days after placement 4. For anterior packing alone, we recommend removal after 48 hours. Where a nasopharyngeal balloon has also been placed, this should be at least partially deflated after 24 hours at the latest. If clinically significant bleeding starts again after packing removal, we advise surgical treatment where possible.

Surgical treatment

When conservative treatment fails, surgical hemostasis is generally required. A Swiss retrospective cohort study showed surgical intervention to be markedly superior to packing in the management of posterior nose bleed (treatment failure rate 3% versus 38%) 15.

The method of choice is endoscopic clipping or coagulation of the sphenopalatine artery 30. A British study reviewed the evidence for endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation and compared it to alternate methods. The former proved to be superior to the other treatment methods (monopolar cautery, embolization, etc.), controlling the bleeding in 98% of cases 31. In retrospective cohort studies, recurrence of bleeding, intranasal dryness with crust formation, sinusitis, impaired nasal and palatal sensitivity, formation of intranasal synechiae, unilateral chronic epiphora, and septal perforation have all been reported as complications. One Brazilian retrospective longitudinal study reported a case of amaurosis after the intervention 32. Taken together, these studies show endoscopic sphenopalatine artery ligation to have few complications 33. Clinically significant hypoxia of the territory supplied by this artery has not been described and is not anticipated, given the multiplicity of anastomoses between the sphenopalatine and ethmoidal arteries 34. For this reason, the criteria for surgical treatment can be quite wide: recurrence of bleeding after one attempt at packing and where the source of the bleeding is not evident 30. Surgical hemostasis should also be considered early on in patients with persistent bleeding despite packing. Endoscopic ligation of the anterior ethmoidal artery is indicated mostly in the context of revision surgery. In four retrospective studies, approximately 2.9% to 8.6% of all patients undergoing surgery for severe nose bleed had anterior ethmoidal artery ligation 35.

Operative procedures

To give the surgeon a better view of the bleeding area, and to reduce blood loss, local and topical use of vasoconstrictors is recommended, together with raising the patient’s head by 15° to 20° 33. In addition, care should be taken to keep the patient hypotensive under anesthesia 33.

- Sphenopalatine artery ligation: A significant landmark for identifying the sphenopalatine artery is the ethmoid crest. This is exposed either by a vertical incision in front of the posterior attachment of the middle nasal concha or via a middle meatal antrostomy with exposure of the posterior wall of the maxillary cavity and abrasion of the mucosa at the maxilloethmoid angle. When the ethmoid crest has been removed, the arterial branches of the sphenopalatine artery that lie behind it are identified and sealed off with a clip (Ligaclip) or by electrocoagulation 33.

- Anterior ethmoidal artery ligation: A less common cause of severe nose bleed is bleeding from the anterior ethmoidal artery, which may occur spontaneously, postoperatively after surgery of the paranasal sinuses, or after trauma. In cases where anterior nose bleed is difficult to control, clipping of the anterior ethmoidal artery is a good therapeutic option. The artery can be located via an open approach in the area of the medial canthus (Lynch incision; transcaruncular approach) or endoscopically. In endoscopic procedures, maxillary antrostomy is carried out and the anterior ethmoidal cells are excavated and the lamina papyracea visualized. Angled lenses are used to locate the anterior ethmoidal artery, which passes through the base of the skull in an anteromedial direction 33. Apart from recurrent bleeding, complications include injury to orbital structures and the base of the skull 33.

- Posterior ethmoidal artery ligation: In rare cases of severe nose bleed, ligation of the posterior ethmoidal artery is indicated. According to a US study, this artery is located an average of 8.1 mm anterior to the anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus 36. Where bleeding persists following the usual surgical and neuroradiological procedures, the French guidelines recommend surgical exploration of the paranasal sinuses with elective coagulation of bleeds from side/secondary branches or ethmoidectomy in patients with diffuse bleeding 37.

Embolization

Another possible method in patients with nose bleed that is difficult to control is percutaneous embolization. This technique has a reported success rate of 87% to 93% 38. The target vessel is imaged angiographically and then an occluding agent is injected via a percutaneous transarterial catheter 39. The embolization should be carried out by an experienced interventional neuroradiologist 37. Because of the potential for complications such as cerebrovascular ischemia, facial nerve paralysis, and soft tissue necrosis, some authors recommend using this technique only in patients who have an increased anesthetic risk because of other comorbidities, or in whom attempted surgical treatment has failed 14. One retrospective cross-sectional study in the US compared embolization with surgical vascular occlusion in terms of morbidity, hospital mortality, and duration of hospital stay. No significant differences were found in relation to blood transfusions (22.8% versus 24.3%), stroke (0.5% versus 0.3%), amaurosis (0.4% versus 0.5%), and hospital mortality. However, surgery is associated with lower hospital costs and a shorter hospital stay 40.

References- Beck R, Sorge M, Schneider A, Dietz A. Current Approaches to Epistaxis Treatment in Primary and Secondary Care. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(1-02):12–22. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0012 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5778404

- Viehweg TL, Roberson JB, Hudson JW. Epistaxis: diagnosis and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:511–518.

- Kubba H, MacAndie C, Botma M, et al. A prospective, single-blind, randomized controlled trial of antiseptic cream for recurrent epistaxis in childhood. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2001;26:465–468.

- Diamond L. Managing epistaxis. JAAPA. 2014;27:35–39.

- Kristensen VG, Nielsen AL, Gaihede M, Boll B, Delmar C. Mobilisation of epistaxis patients—a prospective, randomised study documenting a safe patient care regime. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1598–1605.

- Morgan DJ, Kellerman R. Epistaxis: evaluation and treatment. Primary Care. 2014;41:63–73.

- Szymanska A, Golabek W, Siwiec H, Pietura R, Szczerbo-Trojanowska M. Juvenile angiofibroma: the value of CT and MRI for treatment planning and follow-up. Otolaryngol Pol. 2005;59:85–90.

- Escabasse V, Bequignon E, Verillaud B, et al. Guidelines of the French Society of Otorhinolaryngology (SFORL) Managing epistaxis under coagulation disorder due to antithrombotic therapy. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2016;134:195–199.

- Bequignon E, Vérillaud B, Robard L, et al. Guidelines of the French Society of Otorhinolaryngology (SFORL) First-line treatment of epistaxis in adults. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2017;134:185–189.

- Folz BJ, Kanne M, Werner JA. Aktuelle Aspekte zur Epistaxis. HNO. 2008;56

- Muiesan ML, Salvetti M, Amadoro V, et al. An update on hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. J Cardiovasc Med. 2015;16:372–382.

- Doo G, Johnson DS. Oxymetazoline in the treatment of posterior epistaxis. ¬Hawaii Med J. 1999;58:210–212.

- Chiu TW, McGarry GW. Prospective clinical study of bleeding sites in idiopathic adult posterior epistaxis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:390–393.

- Daudia A, Jaiswal V, Jones NS. Guidelines for the management of idiopathic epistaxis in adults: how we do it. Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33:618–620.

- Soyka MB, Nikolaou G, Rufibach K, Holzmann D. On the effectiveness of treatment options in epistaxis: an analysis of 678 interventions. Rhinology. 2011;49:474–478.

- Johnson N, Faria J, Behar P. A comparison of bipolar electrocautery and ¬chemical cautery for control of pediatric recurrent anterior epistaxis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:851–856.

- Traboulsi H, Alam E, Hadi U. Changing trends in the management of epistaxis. Int J Otolaryngol. 2015;2015 263987.

- Murer K, Soyka MB. Die Behandlung des Nasenblutens [The treatment of ¬epistaxis] Praxis (Bern 1994) 2015;104:953–958.

- Lanier B, Kai G, Marple B, Wall GM. Pathophysiology and progression of nasal septal perforation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:473–480.

- Weber RK. Nasal packing and stenting. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;8 Doc02

- Hettige R, Mackeith S, Falzon A, Draper M. A study to determine the benefits of bilateral versus unilateral nasal packing with Rapid Rhino packs. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:519–523.

- Weber RK. Nasal packing and stenting. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;8 Doc02.

- Beule AG, Weber RK, Kaftan H, Hosemann W. Übersicht: Art und Wirkung ¬geläufiger Nasentamponaden [Review: pathophysiology and methodology of nasal packing] Laryngorhinootologie. 2004;83:534–551;. quiz 553-6

- Martin F. Ballonkatheter als Alternative zur Bellocq-Tamponade (Foley catheter technique as an alternative to bellocq pack [author‘s transl]) Laryngol Rhinol Otol. 1979;58:336–339.

- Lenarz T, Boenninghaus HG. Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heilkunde Berlin, Heidelberg. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2012

- Spillmann D. Aspiration von Nasentamponaden mit Todesfolge. Laryngorhino¬otologie. 1981;60

- Beule AG, Weber RK, Kaftan H, Hosemann W. Übersicht: Art und Wirkung ¬geläufiger Nasentamponaden [Review: pathophysiology and methodology of nasal packing] Laryngorhinootologie. 2004;83:534–551;. quiz 553-6.

- Márquez Moyano JA, Jiménez Luque JM, Sánchez Gutiérrez R, et al. Shock tóxico estafilocócico asociado a cirugía nasal [Toxic shock syndrome associated with nasal packing] Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2005;56:376–378.

- Biswas D, Wilson H, Mal R. Use of systemic prophylactic antibiot¬ics with ¬anterior nasal packing in England, UK. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31:566–567.

- Loughran S, Hilmi O, McGarry GW. Endoscopic sphenopalatine artery liga¬tion—when, why and how to do it An on-line video tutorial. Clin Otolaryngol. 2005;30:539–543.

- Kumar S, Shetty A, Rockey J, Nilssen E. Contemporary surgical treatment of epistaxis What is the evidence for sphenopalatine artery ligation? Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2003;28:360–363.

- Saraceni Neto P, Nunes LMA, Gregório LC, Santos RdP, Kosugi EM. Surgical treatment of severe epistaxis: an eleven-year experience. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;79:59–64.

- Lin G, Bleier B. Surgical management of severe Epistaxis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49:627–637.

- Chiu T, Dunn JS. An anatomical study of the arteries of the anterior nasal septum. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:33–36.

- Bermüller C, Bender M, Brögger C, Petereit F, Schulz M. Epistaxis bei ¬Antikoagulation – eine klinische und ökonomische Herausforderung? Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie. 2014;93:249–255.

- Han JK, Becker SS, Bomeli SR, Gross CW. Endoscopic localization of the ¬anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:931–935.

- Verillaud B, Robard L, Michel J, et al. Guidelines of the French Society of ¬Otorhinolaryngology (SFORL) Second-line treatment of epistaxis in adults. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2017;134:191–193.

- Riemann R. Tipps & Tricks – Epistaxis Management unter Berücksichtigung der Kontamination. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie. 2016;95:11–14.

- Gary L, Ferneini AM. Interventional radiology and bleeding disorders: what the oral and maxillofacial surgeon needs to know. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2016;28:533–542.

- Sylvester MJ, Chung SY, Guinand LA, Govindan A, Baredes S, Eloy JA. Arterial ligation versus embolization in epistaxis management: Counterintuitive national trends. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:1017–1020.