Onychomadesis

Onychomadesis is nail shedding (loss of nail) beginning at the proximal end, possibly caused by the temporary arrest of the function of the nail matrix, and can affect both fingernails and toenails 1. Onychomadesis is a rare disorder in children, and cases were considered to be idiopathic or acquired 2. Most commonly, onychomadesis has been reported in association with pemphigus vulgaris and hand–foot–mouth disease and following chemotherapy or antiepileptic medications 3. Hand–foot–mouth disease viruses are potential risk factors of onychomadesis in children 4. Onychomadesis after hand–foot–mouth disease was first reported in five children in Chicago, USA, 2000 5. Hand-foot-mouth disease is a common illness of children (mainly affecting children older than five years), characterized by fever and vesicles involving the hands, feet and mouth 6. Variable strains of viruses are known to be related, such as coxsackievirus A5, A6, A7, A9, A10, A16, B1, B2, B3, B5; echoviruses E3, E4, E9; and enterovirus 71 7. Enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16 are the most common causative agents among a dozen enteroviruses associated with hand–foot–mouth disease 8. Onychomadesis is a late complication that occurs four to six weeks after the illness onset 9. It is usually self-limited and requires no treatment 10. Nail abnormalities range from leukonychia and Beau lines to partial or complete nail shedding 11. The recise mechanism of onychomadesis associated with hand-foot-and-mouth disease is incompletely understood. Several hypotheses have suggested it may involve brief inhibition of nail-matrix proliferation caused by fever, periungual inflammatory reactions or enteroviruses affecting the nail matrix more directly 11.

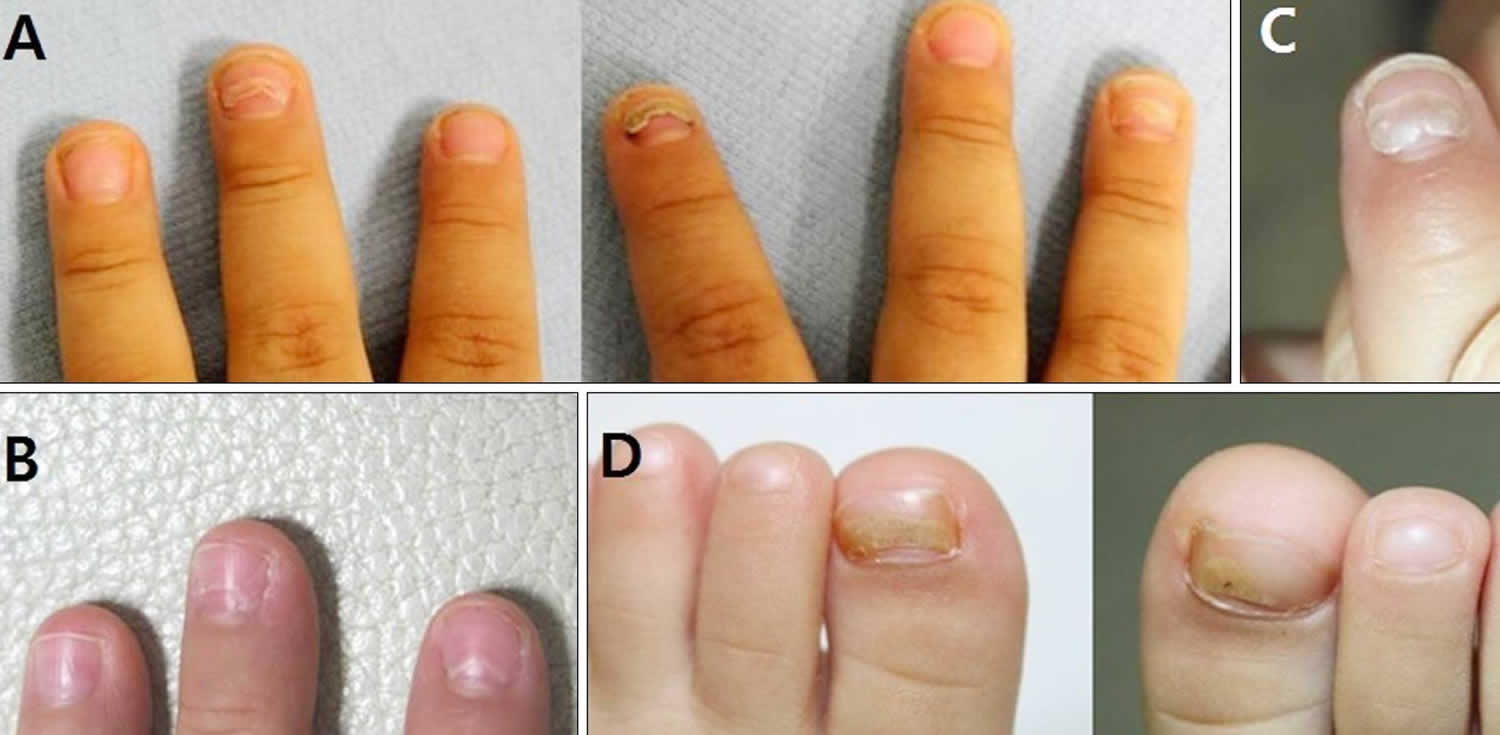

Figure 1. Onychomadesis toddler

Footnote: (A) Three-year-old boy with onychomadesis on the left middle, right index, and right ring fingernails. (B) Four-year-old girl with prominent Beau’s lines on the left index and middle fingernails. (C) Third patient with onychomadesis on the left index fingernail. (D) Eighteen-month-old girl with onychomadesis on both toenails.

[Source 12 ]Figure 2. Onychomadesis in child

Footnote: Partial or complete nail shedding in a seven-year-old boy who had hand-foot-and-mouth disease eight weeks earlier. Panels A–C show new nail growth, panels A, B and D show Beau lines (white arrows), and panels D and E show grey-white color changes (black arrows).

[Source 13 ]Onychomadesis causes

Conditions that can cause onychomadesis include idiopathic, severe systemic diseases, nutritional deficiencies, trauma, periungual dermatitis, chemotherapy, fever, drug ingestion, anticonvulsants and infection 7. Nail matrix arrest with fever, infection, systemic disease or drug exposure can be explained by inflammation in the periungual and matrix regions, inhibition of cellular proliferation, alteration in the quality of manufactured nail plate, and nerve injury or dysfunction 14.

A study of a hand–foot–mouth disease outbreak, of children in Taiwan, showed the incidence of onychomadesis, following infection with a coxsackievirus A6 strain was 37 percent (48/130) compared to 5 percent (7/145) in coxsackievirus A6 infections 15. Additionally, 69 percent (33/48) of patients who developed onychomadesis were reported to experience concomitant palmoplantar desquamation before or at the time of nail changes 16. Another study of a hand–foot–mouth disease outbreak, in Spain, noted differences in the prevalence of onychomadesis in regard to age with a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate seen in the youngest age group (9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (33–42 months). The mean latency period of onychomadesis ensuing hand–foot–mouth disease ranged from 1 to 2 months, average length 40 days, with only an average of 4 nails shed per case 17. To date only a small number of reports of hand–foot–mouth disease-induced onychomadesis in adults have been described in the dermatological literature. It is reported that 11 percent of exposed adults become infected with hand–foot–mouth disease however, fewer than 1 percent develop clinical manifestations 18.

The mechanism of onychomadesis after hand–foot–mouth disease is not fully understood. However, viral infection is responsible for onychomadesis, as a temporal latency exists between hand–foot–mouth disease and onychomadesis. Bettoli et al. 19 reported that inflammation secondary to viral infection around the nail matrix may be induced directly by viruses or indirectly by virus-specific immunocomplexes and consequent distal embolism, and Cabrerizo et al. 20 suggested that virus replication directly damage the nail matrix, based on the presence of coxsackievirus 6 in shed nails. Because fingernails with onychomadesis are not always of the fingers affected by hand–foot–mouth disease, an indirect effect of viral infection on the nail matrix is more plausible. Onychomadesis can also occur on toenails; however, it is less frequent even when vesicles were present on the feet previously. Whether this is due to less frequent detection or a different mechanism is not known.

Onychomadesis symptoms

Depending on the underlying cause, there may be involvement of a single nail or multiple nails. Nag et al noted that onychomadesis was most commonly observed in nails of the middle finger (73.7%), followed by the thumb (63.2%) and ring finger (52.6%). Fingernails are more commonly involved than toenails.

Onychomadesis diagnosis

The diagnosis of onychomadesisis made clinically. Distinct nail changes can be detected by inspection and palpation of the nail plate.

Onychomadesis treatment

Hand–foot–mouth disease-induced onychomadesis is typically self-limited and usually no treatment is indicated. Patient reassurance, hydration, and supportive care are the ideal management for hand–foot–mouth disease 21.

References- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM (2005). Andrews’ diseases of the skin: clinical dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- Salazar A, Febrer I, Guiral S, Gobernado M, Pujol C, Roig J. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain, June 2008. Euro Surveill. 2008;13(27):18917.

- Hardin J, Haber R. Onychomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:592–596. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13339

- Li D, Wu Y, Xing X, et al. Onychomadesis and potential association with HFMD outbreak in a kindergarten in Hubei province, China, 2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):995. Published 2019 Nov 26. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4560-8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6878681

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand–foot–mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17(1):7–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01702.x

- Huang X, Wei H, Wu S, et al. Epidemiological and etiological characteristics of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Henan, China, 2008–2013. Sci Rep 2015;5:8904.

- Davia JL, Bel PH, Ninet VZ, Bracho MA, González-Candelas F, Salazar A, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enteroviruses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:1–5.

- Yan X, Zhang ZZ, Yang ZH, et al. Clinical and etiological characteristics of atypical hand-foot-and-mouth disease in children from Chongqing, China: a retrospective study. BioMed Res Int 2015 Nov. 26 [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1155/2015/802046

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill 2010;15:19663

- Mathes EF, Oza V, Frieden IJ, et al. “Eczema coxsackium” and unusual cutaneous findings in an enterovirus outbreak. Pediatrics 2013;132:e149–57.

- Hardin J, Haber RM. Onychomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol 2015; 172:592–6.

- Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, Cho S. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(6):777-778. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.777 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4252687

- Onychomadesis after hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Xue-ling Gan, Tang-de Zhang. CMAJ Feb 2017, 189 (7) E279; https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.160388

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7–11.

- Swali, Ritu & Siller, Alfredo & Shalabi, Mojahed & Jebain, Joseph & Tyring, Stephen. (2020). Onychomadesis as a Manifestation of Coxsackievirus A6. 10.13140/RG.2.2.28733.69602

- Chiu, H.-H., et al., Onychomadesis following hand-foot-and-mouth disease.Cutis, 2016. 97(5): p. E20-1.

- Guimbao, J., et al., Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008.Eurosurveillance, 2010. 15(37): p. 19663.

- Ramirez-Fort, M.K., et al., Coxsackievirus A6 associated hand, foot and mouth disease in adults: clinical presentation and review of the literature.Journal of Clinical Virology, 2014. 60(4): p. 381-386.

- Bettoli V, Zauli S, Toni G, Virgili A. Onychomadesis following hand, foot, and mouth disease: a case report from Italy and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:728–730.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, Martínez-Risco R, Pousa A, Trallero G. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775–1778.

- Simeonovski, Viktor & Damevska, Katerina & Duma, Silvija & Sotirovski, Tomica & Djoric, Ivana. (2019). Onychomadesis following bullous pemphigoid.