Osler Weber Rendu syndrome

Osler Weber Rendu syndrome also called Osler-Weber-Rendu disease or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, is an inherited disorder that results in the development of abnormal blood vessel connections to develop between arteries and veins, called arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). In Osler Weber Rendu syndrome or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, some arterial vessels flow directly into veins rather than into the capillaries. The most common locations affected are the nose, lungs, brain and liver. These arteriovenous malformations may enlarge over time and can bleed or rupture, sometimes causing catastrophic complications. When they occur in vessels near the surface of the skin, where they are visible as red markings, they are known as telangiectases (the singular is telangiectasia).

Spontaneous and unprovoked nosebleeds, sometimes on a daily basis, are the most common feature in people with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, and more serious problems may arise from hemorrhages in the brain, liver, lungs, or other organs. Persistent bleeding from the nose and the intestinal tract can result in severe iron deficiency anemia and poor quality of life.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasi has been classified into the following four types, though more may exist:

- Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasi type 1

- Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasi type 2

- Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasi type 3

- Juvenile polyposis syndrome and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

There are several forms of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, distinguished mainly by their genetic cause but with some differences in patterns of signs and symptoms. People with type 1 tend to develop symptoms earlier than those with type 2, and are more likely to have blood vessel malformations in the lungs and brain. Type 2 and type 3 may be associated with a higher risk of liver involvement. Women are more likely than men to develop blood vessel malformations in the lungs with type 1, and are also at higher risk of liver involvement with both type 1 and type 2. Individuals with any form of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, however, can have any of these problems.

Juvenile polyposis and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia syndrome is a condition that involves both arteriovenous malformations and a tendency to develop growths (polyps) in the gastrointestinal tract. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia types 1, 2 and 3 do not appear to increase the likelihood of such polyps.

Osler Weber Rendu syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder that you inherit from your parents, which means that if one of your parents has Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, you have a 50 percent chance of inheriting it. If you have Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, each of your children has a 50 percent chance of inheriting it from you. Its severity can vary greatly from person to person, even within the same family. If you have Osler-Weber-Rendu disease or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, you may want to have your children checked for the disease because they can be affected even if they’re not experiencing any symptoms.

The incidence of Osler Weber Rendu syndrome or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is difficult to determine because the severity of symptoms can vary widely and some symptoms, such as frequent nosebleeds, are common in the general population. In addition, arteriovenous malformations may be associated with other medical conditions. Osler Weber Rendu syndrome is widely distributed, occurring in many ethnic groups around the world. It is believed to affect between 1 in 5,000 and 1 in 10,000 people, although, some sources say that it is higher due to variable penetrance and because symptoms do not present until later in adult life 1. Osler-Weber-Rendu disease has a higher prevalence in certain populations, such as the Afro-Caribbean residents of Curacao and Bonaire 2.

Figure 1. Osler Weber Rendu syndrome

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease causes

Mutations in several genes, including the activin A receptor-like type 1 (ACVRL1), endoglin (ENG) and SMAD4 genes, cause Osler Weber Rendu syndrome or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. All these genes provide instructions for making proteins that are found in the lining of the blood vessels. These proteins interact with growth factors that control blood vessel development. Mutations in other genes, some of which have not been identified, account for other forms of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 1.

There are 2 main types of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease that are both caused by heterozygous mutations 3. Osler-Weber-Rendu disease1 involves a mutation in endoglin (ENG). With this type, patients, especially women, are at a higher risk of getting pulmonary and cerebral arteriovenous malformations.

- Osler Weber Rendu syndrome type 1 or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1 is caused by mutations in the ENG gene.

- Osler-Weber-Rendu disease type 2 or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1 involves a mutation in activin A receptor-like type 1 (ACVRL1), also known as ALK1. Patients with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease type 2 have a higher risk of getting liver arteriovenous malformations. ENG comprises about 61%, and ACVRL1 comprises about 37% of the mutations known to cause Osler-Weber-Rendu disease. Mutations in growth differentiation factor 2 (GDF2) have been found. These encode the protein that binds to endoglin and ACVRL1.

- Lastly, there are mutations in SMAD4 which encodes a protein that transmits signals from the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) receptor. This mutation only comprises about 2% of cases. Patients with this gene mutation get juvenile gastrointestinal polyposis and Osler-Weber-Rendu disease 4.

Osler Weber Rendu syndrome inheritance pattern

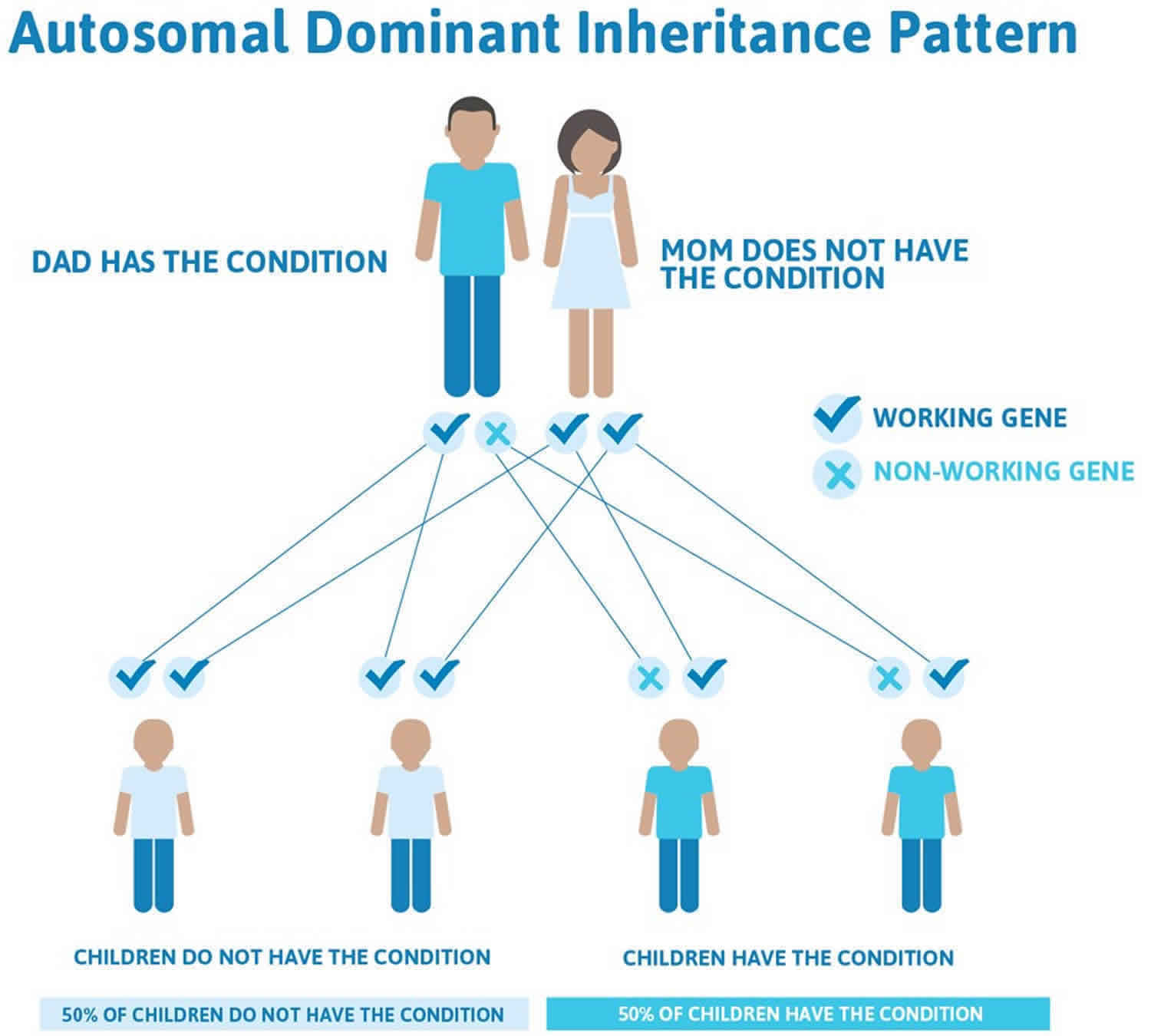

Osler Weber Rendu syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder.

Often autosomal dominant conditions can be seen in multiple generations within the family. If one looks back through their family history they notice their mother, grandfather, aunt/uncle, etc., all had the same condition. In cases where the autosomal dominant condition does run in the family, the chance for an affected person to have a child with the same condition is 50% regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

- When one parent has the abnormal gene, they will pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. Each of their children therefore has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting the changed gene and being affected by the condition.

- There is also a 50% (1 in 2) chance that a child will inherit the normal copy of the gene. If this happens the child will not be affected by the disorder and cannot pass it on to any of his or her children.

Figure 2 illustrates autosomal dominant inheritance. The example below shows what happens when dad has the condition, but the chances of having a child with the condition would be the same if mom had the condition.

Figure 2. Osler Weber Rendu syndrome autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease symptoms

Signs and symptoms of Osler Weber Rendu syndrome or hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia include:

- Nosebleeds (epistaxis), sometimes on a daily basis and often starting in childhood

- Lacy red vessels or tiny red spots (telangiectasias), particularly on the lips, face, fingertips, tongue and inside surfaces of the mouth

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Shortness of breath

- Headaches

- Seizures

The primary and most common manifestation of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease is usually epistaxis (nosebleed) that begins during childhood or adolescence at a mean age of 12 years. Telangiectasias do not usually appear until after puberty but may not occur until adulthood. They typically occur on the face, lips, tongue, palms, and fingers including the periungual area and the nail bed. Telangiectasias are dilated blood vessels that appear as thin spiderweb-like red and dark purple lesions that blanch with pressure. Arteriovenous malformations are abnormal connections between arteries and veins that bypass the capillary system. Patients with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease have multiple arteriovenous malformations throughout the body. However, the most important arteriovenous malformations for which clinicians should screen are in the brain, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and liver. Arteriovenous malformations in the lung and brain can be asymptomatic 5.

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations can cause hypoxemia, hemorrhage, and cerebral abscesses or strokes due to paradoxical emboli. They can lead to the right to left shunting in approximately 15% to 50% of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease patients.

Cerebral arteriovenous malformations can lead to lethal intracranial hemorrhage starting from infancy. They occur in 25% of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease patients.

Spinal arteriovenous malformations can occur in children and can cause acute paraplegia.

Gastrointestinal bleeding can occur from arteriovenous malformations and typically occurs in adults in their 40s. Patients often present with iron deficiency anemia.

Liver arteriovenous malformations can lead to high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, and biliary disease. They present in 30% to 80%, but they are symptomatic in less than 10% of patients 4.

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease diagnosis

Your doctor may diagnose Osler-Weber-Rendu disease based on a physical examination, results of imaging tests and a family history. But some symptoms may not yet be apparent in children or young adults.

The diagnosis of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease is made clinically on the basis of the Curaçao criteria, established in June 1999 by the Scientific Advisory Board of the Osler-Weber-Rendu disease Foundation International 6. The four clinical diagnostic criteria are as follows:

- Epistaxis (spontaneous recurrent epistaxis)

- Mucocutaneous telangiectasias

- Visceral telangiectasias or arteriovenous malformations

- Family history (a first-degree relative with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease)

The Osler-Weber-Rendu disease diagnosis is classified as definite if three or four criteria are present. If they only 1 or 2 criteria are present, then Osler-Weber-Rendu disease is suspected. More than 90% of patients with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease will meet these criteria by 40 years of age.

Because of the life-threatening complications that can occur in a patient who has visceral arteriovenous malformations, it is important to order the appropriate diagnostic tests. Annual blood tests to look at hemoglobin and hematocrit levels should be completed in Osler-Weber-Rendu disease patients over 35 years old.

Your doctor also may suggest you undergo genetic testing for Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, which may confirm a suspected diagnosis. A screen for ENG and ACVRL1 ± SMAD4 and/or GDF2 should be done in those that are at risk because of an affected first-degree relative or are clinically suspected to have Osler-Weber-Rendu disease 4.

Imaging tests

In Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, abnormal connections called arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) develop between arteries and veins. The organs most commonly affected by Osler-Weber-Rendu disease are the lungs, brain and liver. To locate arteriovenous malformations, your doctor may recommend one or more of the following imaging tests:

- Ultrasound imaging. This technique is sometimes used to determine whether the liver is affected by arteriovenous malformations.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Your doctor may order an MRI scan to check your brain for any blood vessel abnormalities. Brain MRI with and without gadolinium should be ordered for suspected and confirmed Osler-Weber-Rendu disease.

- Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: Transthoracic contrast echocardiography should be ordered. If negative, repeat screening should be considered after puberty, within the 5 years preceding a planned pregnancy, after pregnancy, and otherwise every 5 to 10 years. This test is indicated for either suspected or confirmed Osler-Weber-Rendu disease. If positive, confirmation with high-resolution thoracic CT should be performed.

- Liver arteriovenous malformations: Screening via doppler ultrasound or triphasic helical CT is recommended in all patients with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease and abnormal liver enzyme tests or clinical evidence of complications from liver arteriovenous malformations, including high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, and cholestasis.

- Bubble study. To screen for any abnormal blood flow caused by an arteriovenous malformation in a lung, your doctor may recommend a special echocardiogram called a bubble study.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan. If a bubble study reveals a feature that looks like a lung arteriovenous malformation, your doctor may order a CT scan of your lungs to confirm the diagnosis and assess whether you need surgery.

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease treatment

If you or your child has Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, seek treatment at a medical center with experience treating it. Because the disorder is uncommon, finding a specialist in Osler-Weber-Rendu disease can be difficult. In the United States, Osler-Weber-Rendu disease Centers of Excellence are designated by Cure Osler-Weber-Rendu disease for their ability to diagnose and treat all aspects of the disorder.

To help prevent Osler-Weber-Rendu disease nosebleeds, you may want to:

- Avoid certain medications. Your risk of bleeding can be increased by over-the-counter drugs and supplements such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), fish oil supplements, ginkgo and St. John’s wort.

- Avoid certain foods. In some people, Osler-Weber-Rendu disease nosebleeds are triggered when they consume blueberries, red wine, dark chocolate or spicy foods. You might want to keep a food diary to see if there’s any connection between what you eat and the severity of your nosebleeds.

- Keep your nose moist and lubricated at all times. Applying saline sprays and moisturizing ointments can help reduce the risk of bleeding. Using a bedside humidifier overnight also is helpful.

Medications

Drugs that help reduce the bleeding associated with Osler-Weber-Rendu disease can be divided into three broad categories:

- Hormone-related drugs. Medications containing estrogen can be helpful, but side effects are common with the high doses needed. Anti-estrogens such as tamoxifen (Soltamox) and raloxifene (Evista) also have been used to control Osler-Weber-Rendu disease.

- Drugs that block blood vessel growth. One of the most promising treatments for Osler-Weber-Rendu disease is bevacizumab (Avastin) given through a tube in a vein (intravenously). Other drugs that block blood vessel growth are being studied for Osler-Weber-Rendu disease treatment. Examples include pazopanib (Votrient) and pomalidomide (Pomalyst).

- Drugs that slow the disintegration of clots. Tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron, Lysteda) can help stop extreme bleeding in emergencies and may be useful if taken regularly to prevent bleeding.

If you develop iron deficiency anemia, your doctor may also suggest intravenous iron replacement treatments, which usually are more effective than taking iron pills.

Surgical and other procedures for the nose

Severe nosebleeds are one of the most common signs of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease. These sometimes occur on a daily basis and can cause so much blood loss that you become anemic and need frequent blood transfusions or iron infusions.

Procedures to reduce the frequency and severity of nosebleeds may include:

- Ablation. This procedure uses energy from lasers or a high-frequency electrical current to seal the abnormal vessels that are causing the nosebleeds. However, this is typically a temporary solution and the nosebleeds eventually recur.

- Skin graft. Your doctor may suggest taking a skin graft from another part of your body, usually the thigh, to transplant inside your nose.

- Surgically closing the nostrils. If nothing else works, connecting flaps of skin within the nose to permanently close the nostrils is often successful. This is done only in extreme cases when other approaches have failed.

Surgical and other procedures for the lungs, brain and liver

The most common organs affected by Osler-Weber-Rendu disease are the lungs, brain and liver. Procedures to treat arteriovenous malformations in these organs may include:

- Embolization. In this procedure, a long, slender tube is threaded through your blood vessels to the problem area, where a plug or a metal coil is deployed to block blood from entering the arteriovenous malformation, which eventually shrinks and heals. Embolization is often used for lung and brain arteriovenous malformations.

- Surgical removal. In some people, the best option is to surgically remove arteriovenous malformations in the lungs, brain or liver. The location of the AVM, particularly in the brain, can increase the surgical risks.

- Stereotactic radiotherapy. This procedure is used for arteriovenous malformations in the brain. It employs beams of radiation from many different directions, all intersecting at the AVM to destroy it.

- Liver transplant. Rarely, treatment for arteriovenous malformations in the liver is a liver transplant.

Osler-Weber-Rendu disease prognosis

Overall, life expectancy appears to be shortened by Osler-Weber-Rendu disease 7; nevertheless, with appropriate screening and aggressive management, life expectancy for the majority of patients may approach that of the normal population. There is a bimodal distribution of mortality, with peaks at age 50 and then from 60 to 79 related to acute complications 8. Most of the mortality of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease is the result of complications of arteriovenous malformations, particularly in the brain, lungs, and gastrointestinal system.

The prognosis is highly dependent on the severity of the disease—in particular, on the degree of systemic involvement, especially pulmonary, hepatic, and central nervous system involvement. Only 10% of patients die of complications of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease.

The prevalence of brain arteriovenous malformation in Osler-Weber-Rendu disease1 patients is 1000-fold higher than the prevalence in the general population (10 in 100,000), and in Osler-Weber-Rendu disease2 patients it is 100-fold higher 9. Pulmonary and brain arteriovenous aneurysms may appear later in life. Patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations and telangiectasis of the gastrointestinal tract are at risk for life-threatening hemorrhage of the lungs and gastrointestinal tract. Other sites of bleeding may include sites in the kidney, spleen, bladder, liver, meninges, and brain.

Strokes may be either hemorrhagic or ischemic. Of patients who have pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, 2% per year are estimated to have a stroke, and 1% per year are estimated to develop a brain abscess. Retinal arteriovenous aneurysms occur only rarely. Patients are also at risk for high-output cardiac failure, migraines and further sequelae.

Frequent nosebleeds and melena may result from telangiectasia in the nose and gastrointestinal tract. Patients with the severe form of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease have heavy bleeding and resultant iron-deficiency anemia. Recurrent epistaxis is observed in as many as 90% of patients. In half the patients, the epistaxis becomes more serious with age, and blood transfusions are required in 10-30% of patients.

References- Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/hereditary-hemorrhagic-telangiectasia

- Westermann CJ, Rosina AF, De Vries V, de Coteau PA. The prevalence and manifestations of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in the Afro-Caribbean population of the Netherlands Antilles: a family screening. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2003 Feb 01;116A(4):324-8.

- Macri A, Wilson AM, Shafaat O, et al. Osler-Weber-Rendu Disease (Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia, HHT) [Updated 2019 Dec 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482361

- Jackson SB, Villano NP, Benhammou JN, Lewis M, Pisegna JR, Padua D. Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT): A Systematic Review of the Literature. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017 Oct;62(10):2623-2630.

- Guttmacher AE, Marchuk DA, White RI. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995 Oct 05;333(14):918-24.

- Shovlin CL, Guttmacher AE, Buscarini E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome). Am J Med Genet. 2000 Mar 6. 91(1):66-7.

- Sabbà C, Pasculli G, Suppressa P, D’Ovidio F, Lenato GM, Resta F, et al. Life expectancy in patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. QJM. 2006 May. 99(5):327-34.

- Kjeldsen AD, Oxhøj H, Andersen PE, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: screening procedures and pulmonary angiography in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Chest. 1999 Aug. 116(2):432-9.

- Choi EJ, Chen W, Jun K, Arthur HM, Young WL, Su H. Novel brain arteriovenous malformation mouse models for type 1 hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. PLoS One. 2014. 9(2):e88511.