Dysuria

Dysuria is a medical term for painful urination or burning, tingling, or stinging sensation while urinating, which is when you feel pain, discomfort, or burning when you urinate 1, 2. The discomfort may be felt where urine passes out of your body in the tube that carries urine out of your bladder (urethra) or the area surrounding your genitals (perineum). Painful urination may also be felt inside the body. This could include pain in the bladder, prostate (for men), or behind the pubic bone. Sometimes it can be a sign of an infection or other health problem. Painful urination can be caused by several things, but in general causes of dysuria can be divided broadly into two categories, infectious and non-infectious. The most common cause of painful urination or dysuria is urinary tract infection (UTI) in women, especially cystitis (inflammation or infection of the bladder). Other infectious causes include urethritis (urinary tract infection affecting the urethra), sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and vaginitis (inflammation or infection of the vagina). Noninfectious inflammatory causes include a foreign body in the urinary tract and skin conditions (e.g., irritant or contact dermatitis, lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, psoriasis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, Behçet syndrome). Something pressing against the bladder (like a cyst) or a kidney stone stuck near the opening to the bladder can also cause painful urination. Noninflammatory causes of dysuria include medication use, urethral anatomic abnormalities, local trauma, and interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome.

The urinary system is your body’s drainage system for removing wastes and extra water. The urinary system includes two kidneys, two ureters, a bladder, and a urethra (see urinary tract anatomy below).

Sometimes painful urination comes and goes on its own. Other times it is the sign of a problem. If you have any of the following symptoms along with painful urination, see your doctor:

- Drainage or discharge from your penis or vagina.

- Blood in the urine.

- Cloudy or foul-smelling urine.

- Fever.

- Pain that lasts more than 1 day.

- Pain in your back or side (flank pain).

Also see your doctor if you are pregnant and are experiencing painful urination.

Painful urination can be a symptom of a more serious problem. Be sure to tell your doctor:

- About your symptoms and how long you’ve had them.

- About any medical conditions you have, such as diabetes mellitus or AIDS. These conditions could affect your body’s response to infection.

- About any known abnormality in your urinary tract.

- If you are or might be pregnant.

- If you’ve had any procedures or surgeries on your urinary tract.

- If you were recently hospitalized (less than 1 month ago) or stayed in a nursing home.

- If you’re had repeated urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- If you’ve tried any over-the-counter medicines for your pain.

If your doctor thinks you have a UTI, he or she will do a urinalysis. This tests your urine to look for infection. He or she may also order an ultrasound of your kidneys or bladder. This can help find sources of pain, including kidney stones.

Your doctor might think your pain is from vaginal inflammation. If so, he or she may wipe the lining of your vagina with a swab to collect mucus. The mucus will be looked at under a microscope. This will test for yeast or other organisms. Your doctor might think your pain is from an infection in your urethra. He or she may swab it to test for bacteria. If an infection can’t be found, they may suggest other tests.

Treatment of painful urination depends on identifying and treating the underlying cause. If you think you have a urinary tract infection (UTI) it is important to see your doctor. Your doctor can tell if you have a urinary tract infection with a urine test. Treatment is with antibiotics. Your doctor will usually prescribe a course of antibiotics that should get rid of the symptoms in a few days.

See your doctor if:

- Your painful urination persists

- You have drainage or discharge from your penis or vagina

- Your urine is foul-smelling or cloudy, or you see blood in your urine

- You have a fever

- You have back pain or pain in your side (flank pain)

- You pass a kidney or bladder (urinary tract) stone

If you’re pregnant, tell your doctor about any pain you have when you urinate.

Urinary tract anatomy

Urine is generally considered sterile. The urinary tract is the body’s drainage system for removing urine, which is made up of wastes and extra fluid. The urinary system can be divided into the upper urinary tract and lower urinary tract:

- Upper urinary tract consists of the kidneys (renal parenchyma and collecting system) and the ureters

- Kidneys. Two bean-shaped organs, each about the size of a fist. They are located just below your rib cage, one on each side of your spine. Every day, your kidneys filter about 120 to 150 quarts of blood to remove wastes and balance fluids. This process produces about 1 to 2 quarts of urine per day.

- Ureters. Thin tubes of muscle that connect your kidneys to your bladder and carry urine to the bladder.

- Lower urinary tract includes the bladder (responsible for storage and elimination of urine), the urethra (tube through which urine exits the bladder to the outside world), and prostate in men. In the female, the urethra exits the bladder near the vaginal area, the vagina could contribute to contamination of urine specimens. In the male, the urethra exits the bladder, passes through the prostate, and then through the penile urethra. The foreskin when present may contribute to infection in select instances.

- Bladder. A hollow, muscular, balloon-shaped organ that expands as it fills with urine. The bladder sits in your pelvis between your hip bones. A normal bladder acts like a reservoir. It can hold 1.5 to 2 cups of urine. Although you do not control how your kidneys function, you can control when to empty your bladder. Bladder emptying is known as urination.

- Urethra. A tube located at the bottom of the bladder that allows urine to exit the body during urination.

All parts of the urinary tract—the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra—must work together to urinate normally. The urinary tract is important because it filters wastes and extra fluid from the bloodstream and removes them from the body.

Figure 1. Urinary tract anatomy

Figure 2. Urinary bladder anatomy

Figure 3. Urinary bladder anatomy

Burning sensation after urinating causes

There are several conditions that can cause painful urination or dysuria. In women, urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common cause of painful urination. In men, urethritis (urinary tract infection affecting the urethra) and certain prostate conditions are frequent causes of painful urination.

Medical conditions and external factors that can also cause dysuria include:

- Bladder stones

- Something pressing against the bladder. This could be an ovarian cyst or a kidney stone stuck near the entrance to the bladder.

- Vaginal infection or irritation

- Chlamydia trachomatis

- Cystitis (bladder inflammation)

- Medicines, such as those used in cancer treatment (cancer chemotherapy), that have bladder irritation as a side effect

- Genital herpes

- Gonorrhea

- Having a recent urinary tract procedure performed, including use of urologic instruments for testing or treatment

- Kidney infection (pyelonephritis)

- Kidney stones

- Prostatitis (infection or inflammation of the prostate)

- Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) also called sexually transmitted infections (STIs). For example, gonorrhea, chlamydia, or herpes can cause urination to be painful for some people.

- Soaps, perfumes and other personal care products

- Urethral stricture (narrowing of the urethra)

- Urethritis (infection of the urethra)

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Vaginitis

- Yeast infection (vaginal)

- Sensitivity to chemicals in products. Douches, vaginal lubricants, soaps, scented toilet paper, or contraceptive foams or sponges may contain chemicals that cause irritation.

Risk factors for complicated urinary tract infections (increased chance of treatment failure) 3:

- Patient characteristics

- Male sex

- Postmenopausal†

- Pregnant

- Presence of hospital-acquired urinary tract infection

- Symptoms present for seven or more days before presentation

- Medical conditions

- Diabetes mellitus†

- Immunocompromised status

- Urologic conditions

- History of childhood or recurrent urinary tract infections†

- Indwelling catheter

- Neurogenic bladder

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Recent urologic instrumentation

- Renal transplant

- Urolithiasis

- Urologic obstruction

- Urologic stents

Footnote:† Some experts consider the following groups to be uncomplicated: healthy post-menopausal women; patients with well-controlled diabetes; and patients with recurrent cystitis that responds to treatment.

One of the most common causes of dysuria is urinary tract infection (UTI) which occurs in both males and females 2. Urinary tract infections are much more common in females than males is explained by the difference in length of the male and female urethra. In females, bacteria can reach the bladder more easily due to a shorter and straighter urethra compared to males, as the bacterial organisms have far less distance to travel to reach the bladder from the urethral meatus. The average female urethra is approximately 4 cm long, permitting easy entry of bacteria into the bladder and cause infection. The average male urethra is 15-20 cm long, providing better protection against infection by way of its increased length. Besides the increased physical distance bacteria must travel to cause infection, the male urethra has a greater surface area to secrete antibodies to combat infection of the urinary tract. However, males at both ends of the age spectrum (mainly infants <1 year of age and elderly men with prostatic hypertrophy) exhibit a higher incidence of UTI, and other conditions in males (diabetes, spinal cord injury, catheter use) also promote UTI 4. Among individuals with upper-tract UTI (pyelonephritis), males exhibit greater morbidity and mortality than females 5, suggesting that non-anatomical differences may be at work in these more severe infections.

Females who use the wrong wiping technique, from back to front instead of the preferred front to back, take baths instead of showers, or do not use washcloths to clean their vaginal area first when bathing, can predispose themselves to more frequent urinary tract infections due to repeated contamination of the urethral meatus to peri-rectal and other bacteria. Because of their higher likelihood of recurrent urinary tract infections, females also tend to experience dysuria more frequently than males. Most urinary tract infections are uncomplicated and relatively simple to treat. However, persistent dysuria may be associated with complicated urinary tract infections which are found in men with UTIs, incompletely treated simple UTIs, prostatitis, pregnancy, immunocompromised status, catheters, nephrolithiasis, renal failure, dialysis, neurogenic bladder, anatomical or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract, pelvic floor dysfunction, and overactive bladder 6.

The most common cause of male urethritis is infectious from sexually transmitted organisms such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Mycoplasma genitalium. Chlamydia is the most commonly identified cause of non-gonococcal urethritis (found in about 50%), followed by Mycoplasma genitalium 7. Less commonly, other organisms will be found, such as Trichomonas vaginalis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Mycoplasma hominis, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum 8. Refractory cases should have testing for Trichomonas vaginalis. When testing patients suspected or at risk for sexually transmitted infections, consider screening for HIV and syphilis as well.

Gonorrhea is found in about 22% of symptomatic men, with an overall incidence of 213 cases per 100,000 males in 2018, and the incidence is increasing 2. Rates are significantly higher in non-Hispanic African Americans compared with the general population. Rates are also higher in the geographic South compared to other regions in the US. Other parts of the world have even higher rates, such as a reported 62% incidence of gonorrhea in symptomatic men in South Africa 9.

Urethritis associated with bacterial prostatitis is most often caused by gram-negative organisms such as E. coli. Dysuria together with epididymitis is most often caused by Chlamydia trachomatis in men less than 35 years and by E. coli, Pseudomonas, and other gram-negative coliforms in older men.

Dysuria associated with frequency and suprapubic pain without any objective evidence of infection, inflammation, or any other identifiable cause is sometimes called urethral pain syndrome (formerly urethral syndrome) 2. This is very similar to a mild form of interstitial cystitis, which is possibly just a different variety of the same disorder. Both lack positive urine findings of infection. The main clinical differences are 2:

- Urethral pain syndrome has more continuous but somewhat milder dysuria, usually described as a constant irritation. It is possibly related to urethral stenosis and/or hormonal imbalances, although the exact cause is still unknown. Painful spasms of the pelvic musculature are common. Suprapubic discomfort and urinary frequency may be present but are usually not the primary urinary symptoms and are generally not as severe as with interstitial cystitis. Urinary frequency is much more severe during the daytime when it can often require voiding every 30 to 60 minutes with little or no nocturia. Urethral pain syndrome patients are typically female from 13 to 70 years of age.

- Interstitial cystitis typically has more bladder discomfort, frequency, urgency, and pain when the bladder is full and is relieved somewhat upon voiding.

Various foods can increase bladder and urethral irritation, of which caffeine is the most prevalent. High potassium and hot, spicy foods are also considered irritating to the bladder and urethra. Bladder irritating foods 10:

- All alcoholic beverages, including champagne.

- Apples.

- Apple juice.

- Bananas.

- Beer.

- Brewer’s yeast.

- Canned figs.

- Cantaloupes.

- Carbonated drinks.

- Cheese.

- Chicken livers.

- Chilies/spicy foods.

- Chocolate.

- Citrus fruits.

- Coffee.

- Corned beef.

- Cranberries.

- Fava beans.

- Grapes.

- Guava.

- Lemon juice.

- Lima beans.

- Nuts — hazelnuts (also called filberts), pecans and pistachios

- Mayonnaise.

- NutraSweet

- Onions (raw).

- Peaches.

- Pickled herring.

- Pineapple.

- Plums.

- Prunes.

- Raisins.

- Rye bread.

- Saccharin.

- Sour cream.

- Soy sauce.

- Strawberries.

- Tea — black or green, regular or decaffeinated, and herbal blends that contain black or green tea.

- Tomatoes.

- Vinegar.

- Vitamins buffered with aspartame.

- Yogurt.

Determining if a food irritates your bladder is a process of elimination. Not all people sensitive to bladder irritants are affected by the same foods. To test bladder discomfort by eliminating foods, you can:

- Keep a food diary to track foods that are and aren’t irritating.

- Remove the foods listed above from your diet for a few days.

- Once your symptoms are gone, you can begin to add foods in. Start with a small amount of one food, increasing the portion size over several days. If irritation returns after reintroducing a food, stop eating it completely. Repeat food reintroduction slowly to identify your bladder-irritating foods.

Lab tests cannot diagnose foods that cause bladder irritation. But a urologist (healthcare specialist who treats urinary system problems) may examine your bladder to diagnose or rule out interstitial cystitis.

Uncommon causes of dysuria would include endometriosis, atrophic vaginitis, urethral strictures, diverticula, inflammation or infection of the paraurethral/Skene’s glands, syphilis, mycobacterium, herpes genitalis, and infected urachal cysts 11.

Other causes include the presence of a double J urinary stent, recent urethral instrumentation or Foley catheterization, bladder calculi, prostatitis, traumatic sexual intercourse, pelvic floor dysfunction, herpes zoster, and lichen sclerosis.

Topically applied products, such as douches, bubble baths, and contraceptive gels, are also potentially irritating to the urethra. A clinical trial of avoiding any and all topical agents is reasonably warranted.

Overactive bladder will present with urgency and frequency as the primary symptoms. There may also be intermittent suprapubic pain or discomfort.

Painful urination possible complications

Depending on the cause of painful urination, short-term complications can include acute renal failure, development of systemic infection and sepsis, acute anemia from hematuria, urethral strictures with urinary retention, and emergent hospitalizations. Long-term complications consist of developing end-stage renal disease, infertility, long-term disability from recurrent infections, strictures or urinary tract cancers, and even death from severe systemic infections or advanced urinary tract cancers. Patients with complicated urinary tract infections can develop recurrences with greater antibiotic resistance, leading to higher rates of hospitalizations and increased morbidity and mortality 12.

Painful urination diagnosis

Your health care provider will examine you and ask questions such as:

- When did the painful urination begin?

- Does the pain occur only during urination? Does it stop after urination?

- Do you have other symptoms such as back pain?

- Have you had a fever higher than 100°F (37.7°C)?

- Is there drainage or discharge between urinations? Is there an abnormal urine odor? Is there blood in the urine?

- Are there any changes in the volume or frequency of urination?

- Do you feel the urge to urinate?

- Are there any rashes or itching in the genital area?

- What medicines are you taking?

- Are you pregnant or could you be pregnant?

- Have you had a bladder infection?

- Do you have any allergies to any medicines?

- Have you had sexual intercourse with someone who has, or may have, gonorrhea or chlamydia?

- Has there been a recent change in your brand of soap, detergent, or fabric softener?

- Have you had surgery or radiation to your urinary or sexual organs?

In women, the exam will include abdominal and pelvic exams. Your doctor will check for:

- Discharge from the urethra

- Tenderness of the lower abdomen

- Tenderness of the urethra

In men, the exam will include the abdomen, bladder area, penis, and scrotum. The physical exam may show:

- Discharge from the penis

- Tender and enlarged lymph nodes in the groin area

- Tender and swollen penis

- A digital rectal exam will also be performed.

A urinalysis will be done. A urine culture may be ordered. If you have had a previous bladder or kidney infection, a more detailed history and physical exam are needed. Extra lab tests will also be needed. A pelvic exam and exam of vaginal fluids are needed for women and girls who have vaginal discharge. Men who have discharge from the penis may need to have a urethral swab done. However, testing a urine sample may be sufficient in some cases.

The following laboratory tests may be done:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- C-reactive protein test

- Pelvic ultrasound (women only)

- Pregnancy test (women only)

- Urinalysis and urine cultures

- Tests for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and other sexually transmitted illnesses (STI)

- Urethral swab

Further testing may involve repeat testing of urine samples or imaging tests of the urinary tract.

- Imaging tests of your urinary tract. If you are having frequent infections that your doctor thinks may be caused by an abnormality in your urinary tract, you may have an ultrasound, a computerized tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Your doctor may also use a contrast dye to highlight structures in your urinary tract.

- Ultrasound of the kidneys and bladder is the preferred initial test for patients with obstruction, abscess, recurrent infection, or suspected kidney stones, because it avoids radiation exposure 13

- Helical computed tomography urography is used to view the kidneys and adjacent structures, and may be considered to further evaluate patients with possible abscess, obstruction, or suspected anomalies when ultrasonography is not diagnostic 14

- Cystography this is a special type of x-ray of your bladder.

- Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) also known as a micturating cystourethrography (MCU), is a fluoroscopic study of the lower urinary tract in which contrast is introduced into the bladder via a catheter. The purpose of the examination is to assess the bladder, urethra, postoperative anatomy and micturition in order to determine the presence or absence of bladder and urethral abnormalities, including vesicoureteric reflux (VUR). It is more commonly performed for children with UTI than adults.

- Using a scope to see inside your bladder (cystoscopy.). If you have recurrent UTIs, your doctor may perform a cystoscopy, using a long, thin tube with a lens (cystoscope) to see inside your urethra and bladder. The cystoscope is inserted in your urethra and passed through to your bladder.

- Urodynamic studies can be performed for persistent voiding symptoms with otherwise unrevealing workup 15

Table 1. Considerations in Patients with Dysuria and Unremarkable Initial Evaluation

| Condition suspected | Typical presentation | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome | Variable dysuria; frequency and urgency as primary symptoms; pain with bladder filling and relief with emptying are most specific | Initiate conservative treatment (symptom diary to modify fluid intake, diet, and physical activity; bladder training) |

| Overactive bladder | Prominent urgency, frequency, possible urge incontinence | Fluid restriction, bladder training, pelvic floor muscle exercises, drug therapy as needed empirically |

| Potentially offending topical irritant | History of topical use with or without examination findings | Discontinue use of offending agent |

| Suspected bladder irritants | Based on review of medications and diet* | Dietary and medication modification* |

| Urethral diverticulum or endometriosis (women) | Localized symptoms with or without physical examination findings | Urology or gynecology referral |

| Urethritis | Localized symptoms; suspect based on exposures and physical examination | Examination, smears, microscopy, and/or nucleic acid amplification testing |

Footnote: Table 1 lists common conditions that may be causing dysuria, the typical presentation, and management recommendations 3. It is important to use clinical judgment and to be aware of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies on which these algorithms are based. For example, a sexually active adolescent with dysuria is more likely to have an STI than cystitis, and urinalysis results may be negative 16. Similarly, an older patient who experiences dysuria shortly after having an indwelling catheter and who has a negative urinalysis result still has a high likelihood of having a UTI 17.

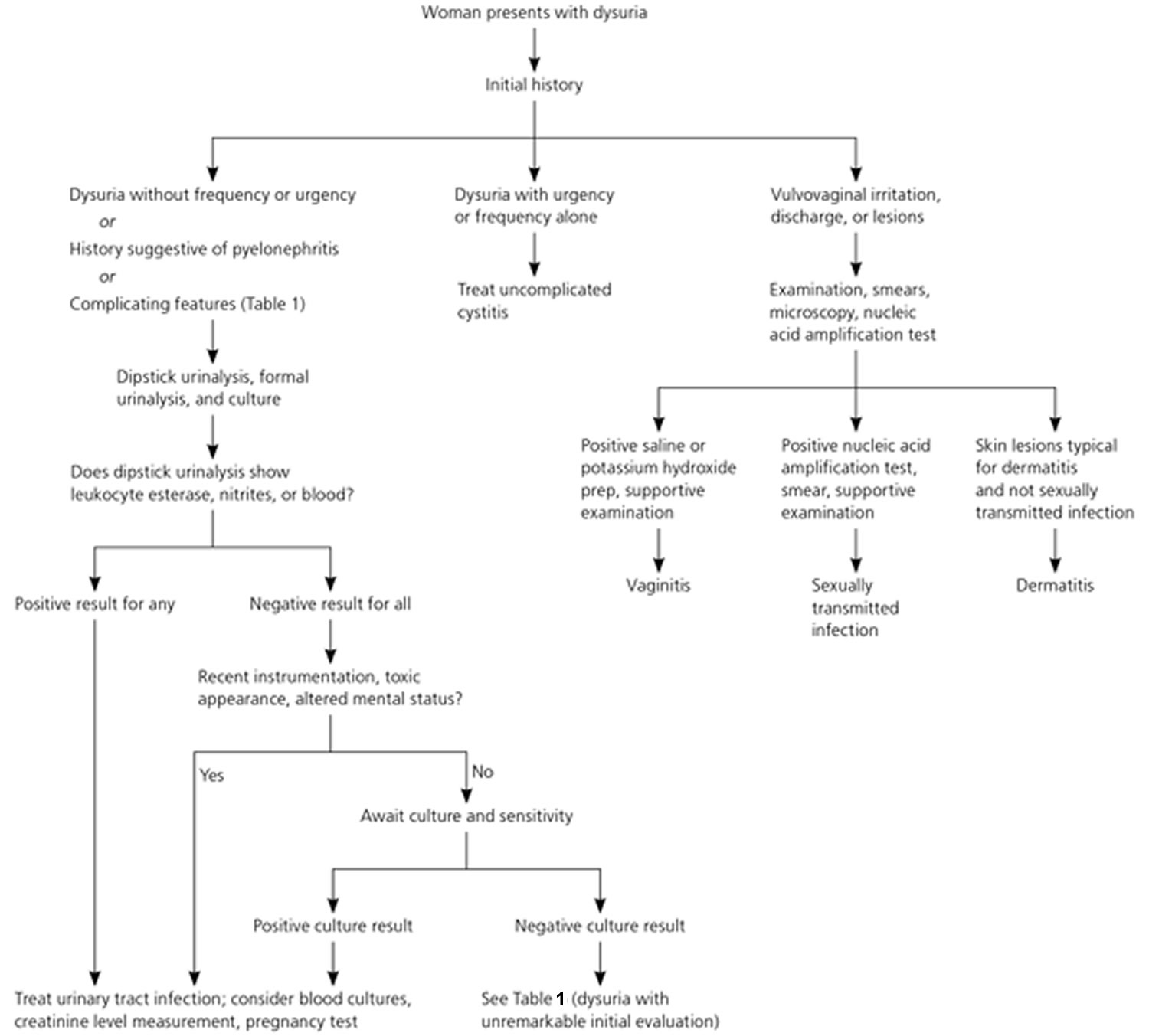

[Source 3 ]Figure 1. Painful urination diagnostic approach in a woman

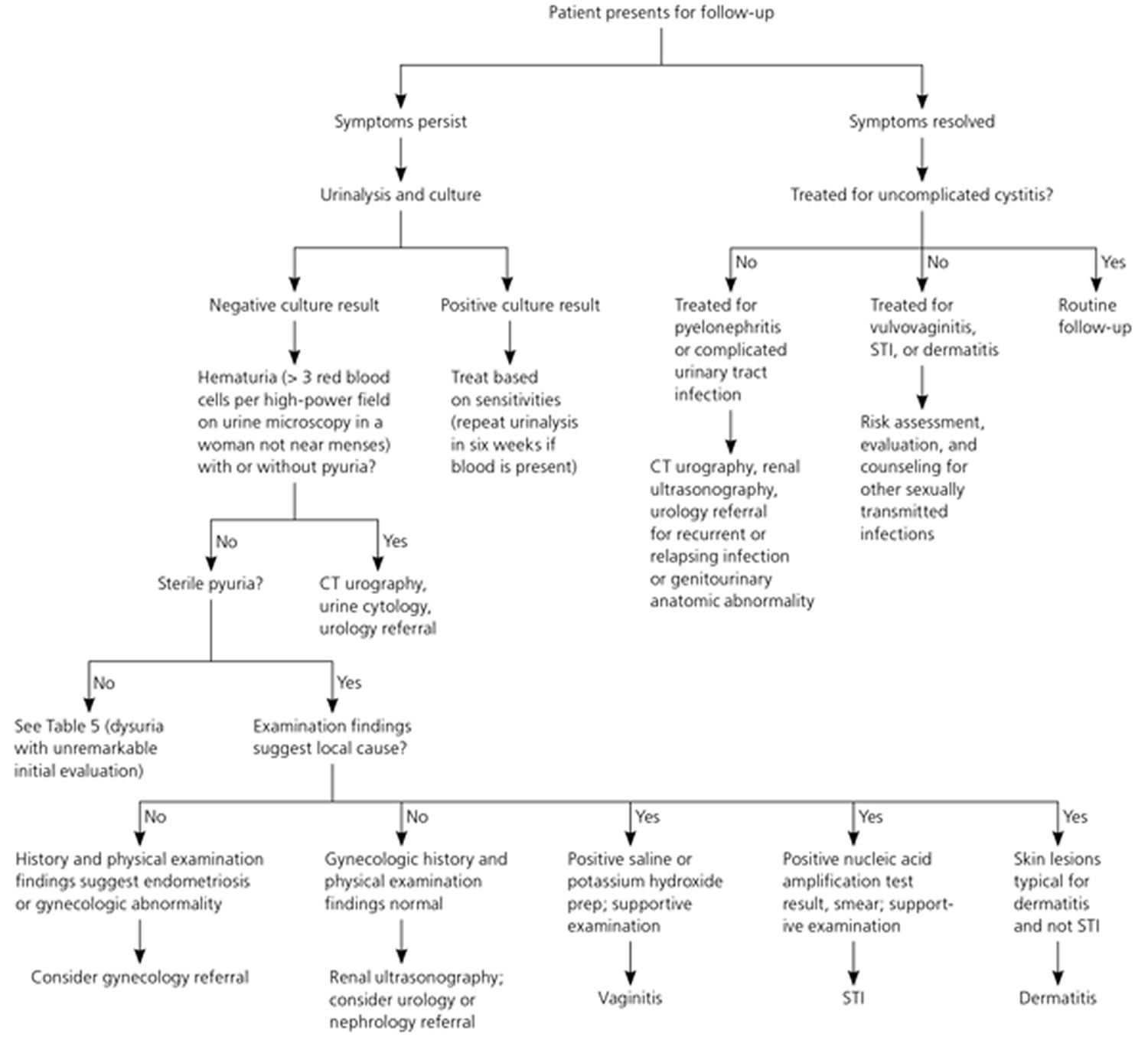

[Source 3 ]Figure 2. Follow-up evaluation in a woman with painful urination

Footnote: Algorithm for the follow-up evaluation in a woman with acute dysuria.

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography; STI = sexually transmitted infection

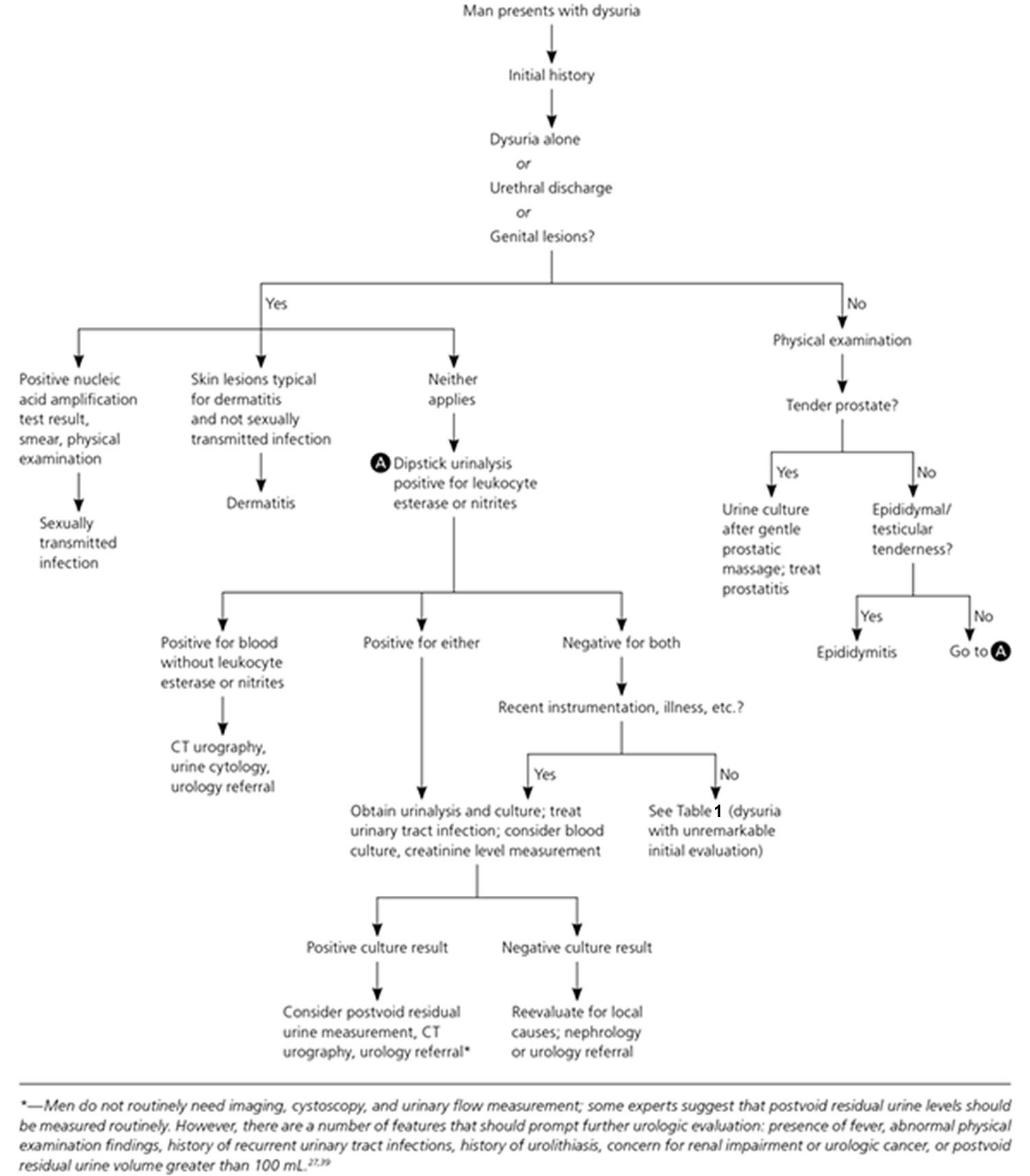

[Source 3 ]Figure 3. Painful urination diagnostic approach in a man

Footnote: Algorithm for the approach in a man with acute dysuria.

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography

[Source 3 ]Urinalysis

Urinalysis is the most useful test in a patient with dysuria; most studies have used dipstick urinalysis. Multiple studies of women with symptoms suggestive of a UTI have demonstrated that the presence of nitrites is highly predictive of a positive culture; dipstick showing more than trace leukocytes is nearly as predictive; and the presence of both is almost conclusive 18, 19. Urinary nitrites may be falsely negative in women with a UTI 20. Few studies specifically address the value of urinalysis in men with dysuria, but evidence suggests similar value to the combination of leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and possibly blood 21, 22. Leukocyte esterase or pyuria alone with isolated dysuria suggests urethritis 23, 24.

Urine culture and cytology

Any patient with risk factors for a complicated UTI or whose symptoms do not respond to initial treatment should have a urine culture and sensitivity analysis. Patients with suspected pyelonephritis should have renal function assessed with serum creatinine measurement, and electrolyte levels should be measured if there is substantial nausea and vomiting. Blood cultures are usually not necessary, but can be obtained in patients with high fever or risk of infectious complications 23.

In women with vaginal symptoms, secretions should be evaluated with wet mount and potassium hydroxide microscopy or a vaginal pathogens DNA probe. Urethritis should be suspected in younger, sexually active patients with dysuria and pyuria without bacteriuria; in men, urethral inflammation and discharge is typically present. In patients with suspected urethritis, a urethral, vaginal, endocervical, or urine nucleic acid amplification test for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis is indicated. Genital ulcerations can be sampled for herpes simplex virus culture or polymerase chain reaction testing, as well as testing for other STIs 25. In men with suspected chronic prostatitis, urine culture after gentle prostatic massage can yield the causative bacterial agent. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level is transiently elevated during acute prostatitis and should not be measured in patients with acute inflammatory symptoms. Urine cytology is helpful if bladder cancer is suspected, such as in older patients with hematuria and a negative culture result 26.

Imaging studies

Imaging is not necessary in most patients with dysuria, although it may be indicated in patients with a complicated UTI, a suspected anatomic anomaly (e.g., abnormal voiding, positive family history of genitourinary anomalies), obstruction or abscess, relapsing infection, or hematuria. Ultrasonography is the preferred initial test for patients with obstruction, abscess, recurrent infection, or suspected kidney stones, because it avoids radiation exposure 27. Helical computed tomography urography is used to view the kidneys and adjacent structures, and may be considered to further evaluate patients with possible abscess, obstruction, or suspected anomalies when ultrasonography is not diagnostic 23. If urinalysis is unrevealing, cystoscopy can be performed to evaluate for bladder cancer, hematuria (blood in urine), and chronic bladder symptoms. Urodynamic studies can be performed for persistent voiding symptoms with otherwise unrevealing workup 28, although a recent Cochrane review found no evidence that these tests led to reduction in symptoms in men with such indications 29. Further investigation and urology referral should be considered in patients with recurrent UTI, urolithiasis, known urinary tract abnormality or cancer, history of urologic surgery, hematuria, persistent symptoms, or in men with abnormal postvoid residual urine level (greater than 100 mL).

Painful urination treatment

Treatment depends on what is causing the painful urination. The most common cause of dysuria is a urinary tract infection (UTI). Antibiotics usually are the first line treatment for urinary tract infections. Which drugs are prescribed and for how long depend on your health condition and the type of bacteria found in your urine. No further evaluation is necessary in those cases where dysuria from uncomplicated urinary tract infection is suspected 30. When the clinician suspects a complicated urinary tract infection, as in the presence of associated symptoms like nausea, vomiting, fever, or chills, then along with starting antibiotics, additional testing like blood cultures, a metabolic panel, or a complete blood count are all viable options. In the case of suspected pyelonephritis, stones, or urinary obstruction, imaging with ultrasonography or CT scan can be diagnostic. In some people, antibiotics do not work or urine tests do not pick up an infection, even though you have UTI symptoms. This may mean you have a long-term (chronic) UTI that is not picked up by current urine tests. Ask your doctor for a referral to a kidney specialist (nephrologist) or urinary surgeon (urologist) for further tests and treatments. Long-term UTIs are linked to an increased risk of bladder cancer in people aged 60 and over.

Antibiotic therapy for urethritis depends on the underlying organism, which is most likely to be sexually transmitted 31. Gonorrhea is treated with ceftriaxone, cefixime, ceftizoxime, cefoxitin, or azithromycin 32. Quinolones are no longer recommended due to increasing resistance. Non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) is usually treated with single-dose azithromycin (1 gram) or doxycycline (100 mg oral twice daily for 7 days) 32. This regimen generally has about an 80% overall cure rate 33. Doxycycline is generally preferred for chlamydia 34. Mycoplasma, a relatively common cause of persistent urethritis, demonstrates resistance to standard therapy with doxycycline, which now has a high failure rate 35. Azithromycin appears to be more effective than doxycycline and is currently recommended for Mycoplasma genitalium and Ureaplasma urealyticum 32. An extended azithromycin regimen, which tends to avoid induced macrolide resistance, is also available (500 mg orally to start, then 250 mg daily for the next four days) 36. This is appropriate for those who fail initial doxycycline therapy. If this regimen fails (azithromycin failures), ten days of moxifloxacin 400 mg daily is recommended 37. Prolonged erythromycin therapy does not appear to be effective and is not recommended. Recurrent symptoms tend to be related to non-compliance, repeat exposure, chronic prostatitis, or infections with Trichomonas vaginalis or Mycoplasma genitalium.

Trichomonas is present in only about 2.5% of male urethritis cases 38. When present, treatment is with metronidazole 2 grams for the patient and his/her partner.

Infrequent causes of urethritis include Treponema pallidum (syphilis) and Haemophilus influenzae which can be transmitted during oral sex 39.

There will be cases where no specific cause of dysuria can be found. In such cases, treatment tends to be symptomatic or holistic. Various generic dysuria treatments include 2:

- Dietary modification. A large variety of foods and beverages have been reported to contribute to dysuria symptoms (see list above). These include alcoholic beverages, highly acidic and spicy foods, hot sauces, condiments, high potassium fruits like bananas, lemons, and tomatoes, fruit juices including cranberry, salad dressings, peppers, chillis, tomato sauces, and ketchup.

- Phenazopyridine. This medication can often relieve the irritation and stinging of dysuria and sometimes the urinary frequency that accompanies it. For best results, it must be taken three times a day. It has an intense orange color when it passes into the urine and will permanently stain anything it touches, so it is best to warn patients of this. The most common side effects are dizziness, headache, and nausea. It is not an antibiotic but a topical analgesic. Since it only provides symptomatic relief and can build up in the body, it is not usually recommended for more than three days continuously. The medication should not be used in patients with known glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency as it can lead to hemolysis 40.

- Calcium glycerophosphate is an OTC medication that purports to reduce urinary acidity to help relieve dysuria. While it appears to help with dysuria in at least some patients, there are no published randomized studies on its efficacy, so evidence on the product is purely anecdotal. It is officially classified as a “medical food” and was originally designed to treat interstitial cystitis. It can be sprinkled over food or taken as a tablet at mealtime. The dietary recommendations are essentially the same as for interstitial cystitis.

- Hydration. Many patients with dysuria will tend to drink less, so they will have to void less often. However, this tends to increase urinary concentrations and ultimately leads to worse burning. Patients should be encouraged to drink more fluid especially water, not less.

- Trial of doxycycline, if not used previously. Doxycycline is a tetracycline-based antibiotic with a unique spectrum of activity that includes many unusual and uncommon organisms. A trial of this antibiotic may cure some patients of otherwise intractable dysuria from an unusual organism 41.

- Trial of azithromycin as Mycoplasma genitalium is a common cause of persistent or intractable urethritis 37.

A clinical trial of estrogen cream in postmenopausal women is a reasonable therapy to try as at least some patients will benefit 42.

Other treatments of dysuria to consider include topical anesthetics, tricyclic antidepressants (such as imipramine or amitriptyline), muscle relaxants, alpha-blockers, urothelial barrier protection enhancement drugs (such as pentosan polysulfate), local steroids, and antibiotics.

Some success has also been reported with behavioral therapy such as biofeedback, meditation, hypnosis, dietary therapy (to increase urinary pH and avoid high urinary potassium as well as other known bladder irritants), acupuncture, botox injections, gabapentin (300 to 600 mg daily) and sertraline (50 – 200 mg daily) therapy 43. Intravesical gentamicin plus betamethasone has also been reported to be of benefit in some dysuria patients 44. Tolterodine can act as both a bladder antispasmodic and anesthetic. A combination of atropine, hyoscyamine methenamine, methylene blue, phenyl salicylate, and benzoic acid is another option; it has both mildly anesthetic and antispasmodic effects. It also will inhibit bacterial growth. It gives the urine a blue-green color.

There is generally no specific surgical treatment for dysuria, but Nd:Yag laser ablation has shown some promise in carefully selected female patients with symptoms refractory to medical therapy. Laser ablation of squamous metaplasia of the trigone and bladder neck areas has shown success in some patients with trigonitis 45. The initial necrotic tissue coagulation immediately after laser ablation is followed by regrowth of normal urothelium 45.

Painful urination prognosis

The prognosis for dysuria depends upon the cause of dysuria. Most of the causes of burning sensation in urine, including inflammatory and non-inflammatory, demonstrate a good long-term prognosis, but early detection and treatment of the underlying causes of the dysuria are essential. Sepsis occurring due to urinary tract infections can lead to higher morbidity and mortality than systemic infections of other organs or systems although urosepsis still has a better overall prognosis 46. Long-term complications can occur due to stones, chronic infections, or benign prostatic hypertrophy, potentially leading to renal failure and, in severe cases, end-stage renal disease. During pregnancy, both maternal and fetal complications can arise if urinary tract infections do not receive treatment timely and adequately 47. Prognosis of dysuria occurring from neoplastic causes like renal cancers or bladder cancers depends upon the stage and type of cancer when it gets diagnosed. Early diagnosis and quick follow-up with adequate treatment carry a good prognosis, while a delayed diagnosis is associated with higher recurrence and poor prognosis 48.

References- Gerber GS, Brendler CB. Evaluation of the urologic patient: history, physical examination, and urinalysis. In: Wein AJ, et al.; eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:75–76.

- Mehta P, Leslie SW, Reddivari AKR. Dysuria. [Updated 2022 Feb 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549918

- Dysuria: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis in Adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Nov 1;92(9):778-788. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2015/1101/p778.html

- Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Dis Mon. 2003 Feb;49(2):53-70. doi: 10.1067/mda.2003.7

- Foxman B, Klemstine KL, Brown PD. Acute pyelonephritis in US hospitals in 1997: hospitalization and in-hospital mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 2003 Feb;13(2):144-50. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00272-7

- Geerlings SE. Clinical Presentations and Epidemiology of Urinary Tract Infections. Microbiol Spectr. 2016 Oct;4(5). doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0002-2012

- Gaydos, C., Maldeis, N. E., Hardick, A., Hardick, J., & Quinn, T. C. (2009). Mycoplasma genitalium compared to chlamydia, gonorrhoea and trichomonas as an aetiological agent of urethritis in men attending STD clinics. Sexually transmitted infections, 85(6), 438–440. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2008.035477

- Horner P, Blee K, O’Mahony C, Muir P, Evans C, Radcliffe K; Clinical Effectiveness Group of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. 2015 UK National Guideline on the management of non-gonococcal urethritis. Int J STD AIDS. 2016 Feb;27(2):85-96. doi: 10.1177/0956462415586675

- Black V, Magooa P, Radebe F, Myers M, Pillay C, Lewis DA. The detection of urethritis pathogens among patients with the male urethritis syndrome, genital ulcer syndrome and HIV voluntary counselling and testing clients: should South Africa’s syndromic management approach be revised? Sex Transm Infect. 2008 Aug;84(4):254-8. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.028464

- Bladder-Irritating Foods. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/14244-bladder-irritating-foods

- Miklovic T, Davis P. Dysuria, Rebound Tenderness, and a Palpable Mass-A Ticking Time Bomb. Mil Med. 2021 Apr 30:usab180. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usab180

- Bleidorn, J., Hummers-Pradier, E., Schmiemann, G., Wiese, B., & Gágyor, I. (2016). Recurrent urinary tract infections and complications after symptomatic versus antibiotic treatment: follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. German medical science : GMS e-journal, 14, Doc01. https://doi.org/10.3205/000228

- Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J, et al. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371(12):1100–1110.

- Gupta K, Trautner B. In the clinic. Urinary tract infection. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(5):ITC3-1–ITC3-15.

- Hanno PM, Erickson D, Moldwin R, Faraday MM. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: AUA guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015;193(5):1545–1553.

- Shapiro T, Dalton M, Hammock J, Lavery R, Matjucha J, Salo DF. The prevalence of urinary tract infections and sexually transmitted disease in women with symptoms of a simple urinary tract infection stratified by low colony count criteria. Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Jan;12(1):38-44. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.051

- D’Agata, E., Loeb, M. B., & Mitchell, S. L. (2013). Challenges in assessing nursing home residents with advanced dementia for suspected urinary tract infections. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(1), 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12070

- Knottnerus, B. J., Geerlings, S. E., Moll van Charante, E. P., & Ter Riet, G. (2013). Toward a simple diagnostic index for acute uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Annals of family medicine, 11(5), 442–451. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1513

- den Heijer, C. D., van Dongen, M. C., Donker, G. A., & Stobberingh, E. E. (2012). Diagnostic approach to urinary tract infections in male general practice patients: a national surveillance study. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 62(604), e780–e786. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12X658313

- Devillé, W. L., Yzermans, J. C., van Duijn, N. P., Bezemer, P. D., van der Windt, D. A., & Bouter, L. M. (2004). The urine dipstick test useful to rule out infections. A meta-analysis of the accuracy. BMC urology, 4, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-4-4

- Raynor MC, Carson CC 3rd. Urinary infections in men. Med Clin North Am. 2011 Jan;95(1):43-54. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.015

- Guralnick ML, O’Connor RC, See WA. Assessment and management of irritative voiding symptoms. Med Clin North Am. 2011 Jan;95(1):121-7. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.025

- Gupta K, Trautner B. In the clinic. Urinary tract infection. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Mar 6;156(5):ITC3-1-ITC3-15; quiz ITC3-16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-01003

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, Wullt B, Colgan R, Miller LG, Moran GJ, Nicolle LE, Raz R, Schaeffer AJ, Soper DE; Infectious Diseases Society of America; European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 1;52(5):e103-20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257

- STI Treatment Guidelines Update 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/default.htm

- Lotan Y, Roehrborn CG. Sensitivity and specificity of commonly available bladder tumor markers versus cytology: results of a comprehensive literature review and meta-analyses. Urology. 2003 Jan;61(1):109-18; discussion 118. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02136-2

- Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J, Bengiamin RN, Camargo CA Jr, Corbo J, Dean AJ, Goldstein RB, Griffey RT, Jay GD, Kang TL, Kriesel DR, Ma OJ, Mallin M, Manson W, Melnikow J, Miglioretti DL, Miller SK, Mills LD, Miner JR, Moghadassi M, Noble VE, Press GM, Stoller ML, Valencia VE, Wang J, Wang RC, Cummings SR. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 18;371(12):1100-10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404446

- Hanno PM, Erickson D, Moldwin R, Faraday MM; American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: AUA guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015 May;193(5):1545-53. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.086

- Clement KD, Burden H, Warren K, Lapitan MC, Omar MI, Drake MJ. Invasive urodynamic studies for the management of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men with voiding dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 28;(4):CD011179. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011179.pub2

- Booth, J. L., Mullen, A. B., Thomson, D. A., Johnstone, C., Galbraith, S. J., Bryson, S. M., & McGovern, E. M. (2013). Antibiotic treatment of urinary tract infection by community pharmacists: a cross-sectional study. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 63(609), e244–e249. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X665206

- Workowski, K. A., Bolan, G. A., & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports, 64(RR-03), 1–137. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5885289

- Garcia MR, Wray AA. Sexually Transmitted Infections. [Updated 2021 Jul 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560808

- Manhart, L. E., Gillespie, C. W., Lowens, M. S., Khosropour, C. M., Colombara, D. V., Golden, M. R., Hakhu, N. R., Thomas, K. K., Hughes, J. P., Jensen, N. L., & Totten, P. A. (2013). Standard treatment regimens for nongonococcal urethritis have similar but declining cure rates: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 56(7), 934–942. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis1022

- Chlamydial Infections. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/chlamydia.htm

- Wikström, A., & Jensen, J. S. (2006). Mycoplasma genitalium: a common cause of persistent urethritis among men treated with doxycycline. Sexually transmitted infections, 82(4), 276–279. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2005.018598

- Weinstein SA, Stiles BG. Recent perspectives in the diagnosis and evidence-based treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012 Apr;10(4):487-99. doi: 10.1586/eri.12.20

- Manhart, L. E., Broad, J. M., & Golden, M. R. (2011). Mycoplasma genitalium: should we treat and how?. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 53 Suppl 3(Suppl 3), S129–S142. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir702

- Wetmore, C. M., Manhart, L. E., Lowens, M. S., Golden, M. R., Whittington, W. L., Xet-Mull, A. M., Astete, S. G., McFarland, N. L., McDougal, S. J., & Totten, P. A. (2011). Demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of men with nongonococcal urethritis differ by etiology: a case-comparison study. Sexually transmitted diseases, 38(3), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182040de9

- Ito S, Hatazaki K, Shimuta K, Kondo H, Mizutani K, Yasuda M, Nakane K, Tsuchiya T, Yokoi S, Nakano M, Ohinishi M, Deguchi T. Haemophilus influenzae Isolated From Men With Acute Urethritis: Its Pathogenic Roles, Responses to Antimicrobial Chemotherapies, and Antimicrobial Susceptibilities. Sex Transm Dis. 2017 Apr;44(4):205-210. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000573

- Diagnosis and Management of G6PD Deficiency. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Oct 1;72(7):1277-1282. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/1001/p1277.html

- Phillip H, Okewole I, Chilaka V. Enigma of urethral pain syndrome: why are there so many ascribed etiologies and therapeutic approaches? Int J Urol. 2014 Jun;21(6):544-8. doi: 10.1111/iju.12396

- YOUNGBLOOD VH, TOMLIN EM, WILLIAMS JO. Senile urethritis in women. Gynaecologia. 1960;149(Suppl):76-9. doi: 10.1159/000306163

- Cakici, Ö. U., Hamidi, N., Ürer, E., Okulu, E., & Kayigil, O. (2018). Efficacy of sertraline and gabapentin in the treatment of urethral pain syndrome: retrospective results of a single institutional cohort. Central European journal of urology, 71(1), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.5173/ceju.2018.1574

- Palleschi G, Carbone A, Ripoli A, Silvestri L, Petrozza V, Zanello PP, Pastore AL. A prospective study to evaluate the efficacy of Cistiquer in improving lower urinary tract symptoms in females with urethral syndrome. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2014 Dec;66(4):225-32.

- Costantini E, Zucchi A, Del Zingaro M, Mearini L. Treatment of urethral syndrome: a prospective randomized study with Nd:YAG laser. Urol Int. 2006;76(2):134-8. doi: 10.1159/000090876

- Qiang, X. H., Yu, T. O., Li, Y. N., & Zhou, L. X. (2016). Prognosis Risk of Urosepsis in Critical Care Medicine: A Prospective Observational Study. BioMed research international, 2016, 9028924. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9028924

- Wrenn K. Dysuria, Frequency, and Urgency. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 181.

- Yaxley J. P. (2016). Urinary tract cancers: An overview for general practice. Journal of family medicine and primary care, 5(3), 533–538. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.197258