Pericardiectomy

Pericardiectomy also called pericardial stripping, is a surgical procedure done to remove of a portion or all of the pericardium (the sac around the heart). A surgeon cuts away this sac or a large part of this sac. This allows the heart to move freely.

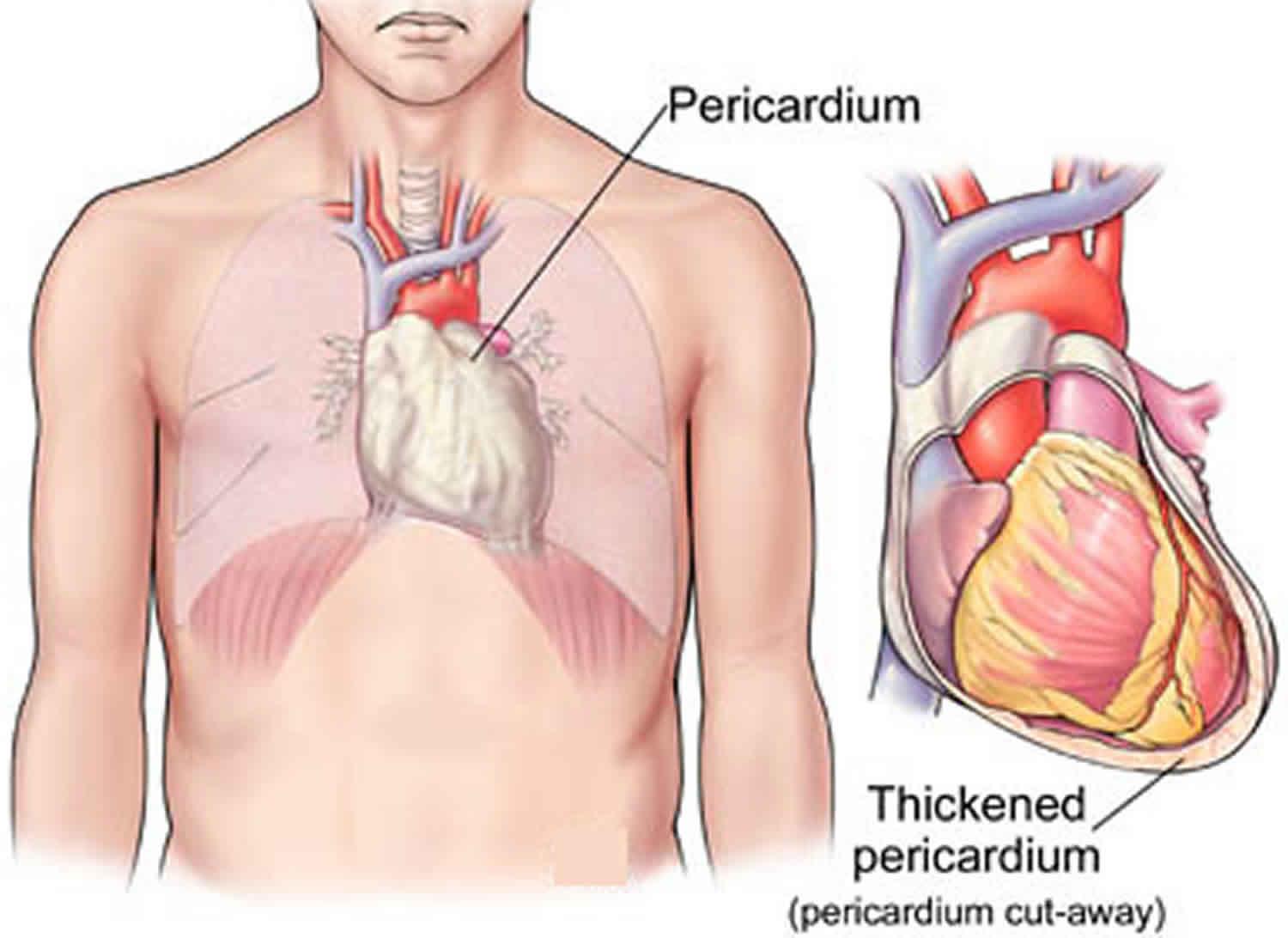

The pericardium is a double-walled, membrane sac with fluid between them that surrounds your heart. This fluid reduces friction as the 2 layers rub against each other when the heart beats. Normally, this sac or pericardium is thin and flexible, but repeated inflammation can cause it to become stiff and thick. When this happens, the heart can’t stretch properly as it beats. This can prevent the heart from filling up with as much blood as it needs. The lack of blood can cause increased pressure in the heart, a condition called constrictive pericarditis. Cutting this sac away allows the heart to fill normally again. Pericardiectomy, however, doesn’t fix the problem that was causing the inflammation.

Pericardiectomy is considered a major cardiac surgery. You may have to stay in the hospital for 5-7 days after surgery. You may be advised not to lift heavy weights. You may require 6-8 weeks to recover completely. As a part of follow-up treatment, your cardiologist may recommend an echocardiogram to evaluate the functioning of your heart. You may be prescribed lower doses of diuretics after surgery.

The most common reason for performing a pericardiectomy is constrictive pericarditis, a condition in which the pericardium has become stiff and calcified. The stiff pericardium prevents the heart from stretching as it normally does when it beats. This causes the heart chambers to fill incompletely with blood, and blood backs up behind the heart. The heart swells, and symptoms of heart failure develop.

Pericardiectomy also can be used to treat recurrent pericarditis, in patients with intractable recurrent symptoms and complications of the anti-inflammatory medications including steroids.

As with all surgical procedures, pericardiectomy may be associated with certain complications, which may include bleeding, requirement of cardiopulmonary bypass (blood is bypassed around a blocked vessel) during the procedure, blood transfusion and sometimes even death. Women, elderly patients, and those suffering from other medical problems such as diabetes are at a greater risk for complications.

Pericardiectomy is performed by a cardiothoracic surgeon. Surgeons and hospitals with experience in this highly specialized surgery achieve the best results with the lowest risk of complications.

The cardiothoracic surgeon should be part of a team of heart specialists, including cardiologists, radiologists and other specialists who collaborate on diagnosing the problem and planning the most effective treatment.

What is the function of the pericardium?

The pericardium protects the heart from infection and other sources of disease and holds the heart in the chest wall. The pericardium contains about 50 cc of fluid that lubricates the heart during its normal pumping movements and prevents friction between the heart and the pericardium lining. The pericardium prevents the heart from over-expanding and keeps it functioning normally when blood volume increases due to conditions such as kidney failure, pregnancy or other causes.

Figure 1. Pericardium

Figure 2. Heart pericardium

Figure 3. Pericardium location

What causes constrictive pericarditis?

Constrictive pericarditis is caused by thickening of the pericardium. Constrictive pericarditis causes diastolic dysfunction and at the end the filling of heart is impeded by the constricted pericardium surrounding the heart 1. There are a number of causes for constrictive pericarditis. At one time, most cases of constrictive pericarditis were idiopathic, meaning the underlying cause was not known. In the past 20 years, this has shifted, and previous heart surgery and radiation to the chest are now leading causes of constrictive pericarditis.

Some other causes of constrictive pericarditis include 2:

- Diseases such as tuberculosis and mesothelioma,

- Viral or bacterial infection,

- Surgical complications,

- Postinfective,

- Connective tissue disease-related,

- Neoplastic,

- Uremic,

- Sarcoidosis, and miscellaneous.

After occurrence of constriction; the symptoms related to fluid overload and reduced cardiac output are progressive in nature.

The study conducted by Ling et al. 3 revealed that the majority of patients presented with congestive heart failure. With decreasing frequencies the patients had presented with chest pain, abdominal symptoms, cardiac tamponade, atrial arrhythmia and frank liver disease.

Definitive treatment for chronic constrictive pericarditis is pericardiectomy.

Constrictive pericarditis surgery

European Society of Cardiology

The European Society of Cardiology released updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of constrictive pericarditis in 2015, which are summarized below 4.

- Transthoracic echocardiography as well as frontal and lateral chest radiography with adequate technical characteristics are recommended in all patients with suspected constrictive pericarditis.

- Computed tomography (CT) scanning and/or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) are indicated as second-level imaging techniques to assess calcifications (CT scanning), pericardial thickness, and degree and extension of pericardial involvement.

- Cardiac catheterization is indicated when noninvasive diagnostic methods do not provide a definite diagnosis of constriction.

- The mainstay of treatment of chronic constriction is pericardiectomy.

- Medical therapy for specific etiologies of pericarditis is recommended to prevent progression of constriction, as well as for advanced cases or in the setting of a high risk of surgery or mixed forms with myocardial involvement.

- Empiric anti-inflammatory therapy may be considered in cases with transient or a new diagnosis of constriction with concomitant evidence of pericardial inflammation on CT/cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) or results of laboratory studies suggestive of inflammation (eg, elevated C-reactive protein [CRP] or erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]).

No medications are required when the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis is definitive, because the patient is usually referred for surgical management. To help maintain a euvolemic state, diuretics and afterload-reducing medications should be used cautiously; decreasing preload or afterload can cause greater compression of the heart and sudden cardiac decompensation, especially when general anesthetic agents are administered just before the pericardiectomy is performed.

What options besides surgery are available for treating constrictive pericarditis?

Patients with less severe pericardium constriction may be treated with anti-inflammatory medications. When constriction of the pericardium comes on relatively quickly (within 3-6 months), a syndrome called transient constriction, it may be due in part to inflammation of the pericardium, and this condition may resolve with medications.

For the most advanced cases, surgical treatment is the best option and the one that doctors recommend.

Pericardiectomy indications

Pericardiectomy is commonly performed in patients suffering from constrictive pericarditis. During constrictive pericarditis, the pericardium becomes stiff and calcified. This prevents the heart from functioning normally. Constrictive pericarditis may be caused due to viral or bacterial infections, tuberculosis, mesothelioma (cancer in the lining of the lungs or abdomen) or surgical complications. Pericardiectomy is also indicated for the treatment of recurrent pericarditis (re-occurrence of pericarditis).

Pericardiectomy procedure

Pericardiectomy can be a long and often technically complex procedure. The 2 standard approaches are via an anterolateral thoracotomy and via a median sternotomy.

Pericardiectomy is performed through a median sternotomy, an incision through the breastbone (sternum) in the middle front part of the ribs that allows the surgeon to reach the heart. The surgeon will remove the pericardium from the heart, wire the breastbone and ribs back together and close the incision with stitches. Other surgeons may use an anterolateral thoracotomy approach. An excimer laser can be used should severe adhesions occur between the pericardium and epicardium 5.

A pericardiectomy cannot safely be done minimally invasively.

Pericardial decortication should be as extensive as possible, especially at the diaphragmatic-ventricular contact regions.

How long do patients stay in the hospital after pericardiectomy?

Most patients stay in the hospital for five to seven days.

How long is the recovery after pericardiectomy?

Patients are permitted to return to their normal activities when they get home, except for lifting. Full recovery after pericardiectomy requires six to eight weeks, depending on how serious the patient’s condition was before the surgery. For the sickest patients before surgery, recovery can take longer than eight weeks.

When do patients feel improvement after surgery?

Patients with severe pericardial constriction who do not have other heart or lung disease often feel improvement immediately after surgery. Most patients notice significant improvement by six to eight weeks and gradually continue improving for a time after the initial recovery period.

Pericardiectomy complications

Pericardiectomy complications may include excessive bleeding, atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, and ventricular wall ruptures.

In published reports, surgical mortality ranges from 5% to 15%, with one report citing a 30-day perioperative mortality of 6.1%. The causes of death include progressive heart failure, sepsis, renal failure, respiratory failure, and arrhythmia. Between 80% and 90% of patients who undergo pericardiectomy achieve New York Heart Association class 1 (i.e., asymptomatic) or 2 (symptoms may be clinically stable for years) postoperatively.

To evaluate the clinical outcome of pericardiectomy, investigators studied 99 consecutive patients who underwent pericardiectomy at the Montreal Heart Institute over a 20-year period 6. They found that hospital mortality was 7.9% in the case of isolated pericardiectomy and that the patients who were operated on within 6 months of symptom onset showed a lower mortality risk. Preoperative clinical conditions and associated comorbidities were critical in predicting mortality risk, and pericardiectomy was able to improve functional status in the majority of late survivors 6.

Even though symptoms are commonly alleviated after a pericardiectomy, evidence of abnormal diastolic filling (which can be correlated with clinical status) often remains. One study found that only 60% of patients showed complete normalization of cardiac hemodynamics 5. Although some patients improved with time, persistent diastolic filling abnormalities tended to occur in those who had a longer history of preoperative symptoms, supporting the view that early operation is advisable in symptomatic patients. Those patients who have symptoms that persist even after successful pericardiectomy may have a more mixed constrictive-restrictive picture.

Of 58 patients who underwent total pericardiectomy for constriction, 30% still had some significant symptoms after 4 years. These patients were more likely to have a persistent restrictive or constrictive pattern to their transmitral and transtricuspid Doppler signals as determined by respiratory recording.

In a study 7 comprising 25 patients who underwent pericardiectomy due to symptomatic chronic constrictive pericarditis (reduced exercise capacity and sleep-disordered breathing), there was improvement in peak rate of oxygen uptake, quality of life, and sleep, but no significant change in sleep disordered breathing.

Different methods of accessing the pericardial space, such as video-assisted thoracoscopy, are being investigated. Further development of such devices may help improve diagnostic and therapeutic options in patients with pericardial disease 8.

Cardiac mortality and morbidity seem to be related to preoperative myocardial atrophy or fibrosis, which can be detected by means of computed tomography (CT) scanning. Excluding these patients keeps the mortality rate at the lower end of the range (5%) 5.

Postoperatively, low cardiac output may occur in patients who are debilitated and who have ascites or other findings of fluid retention. Patients with low cardiac output may require maintenance of high left atrial pressure, sympathomimetic infusions, or both. Mechanical support of the circulation, such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation, can be used in patients who are critically ill.

Pericardiectomy risks

Pericardiectomy is a major cardiac surgery procedure. To minimize risks it should be performed only by a cardiothoracic surgeon experienced in the procedure. The risks of the procedure include the need for cardiopulmonary bypass during surgery, bleeding complications, the need for blood transfusion and death. Older patients, women and patients with other medical problems are at greater risk for complications.

Pericardiectomy prognosis

The pericardium is not essential for normal heart function. In patients with pericarditis, the pericardium already has lost its lubricating ability so removing it does not make that situation worse. Removing the pericardium does not cause problems as long as the patient’s lungs and diaphragm (the large, dome-shaped muscle below the lungs involved in breathing) are intact.

The long-term outlook or prognosis after pericardiectomy depends on the cause of the constrictive pericarditis. A study published in 2004 that tracked 163 patients over 24 years found that the highest long-term survival was in patients with idiopathic constrictive pericarditis, followed by previous surgery causes and radiation therapy. Tuberculosis and heart attack had survival rates comparable with idiopathic causes. In general, younger patients have higher survival rates than older patients, and healthier patients have better survival rates than patients with other medical conditions.

Life after pericardiectomy

Cardiothoracic surgeons recommend that patients see their cardiologist for an echocardiogram six weeks after surgery then at recommended intervals. An echocardiogram is an ultrasound of the heart that allows the cardiologist to see how well the heart is pumping. Most patients will continue to take a diuretic after surgery but in lower doses than were required prior to surgery.

Is it safe for a patient who has had pericardiectomy to undergo other heart surgeries at a later time?

Scar tissue will form around the heart after pericardiectomy and may form between the heart and surrounding structures such as the lungs and diaphragm. This makes further heart surgeries somewhat challenging but not impossible for experienced cardiac surgeons.

Pericardiectomy long term effects

Pericardiectomy is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. The variability of the mortality rates is due to study groups belonging to different causal diseases. Cases with neoplastic diseases, diminished cardiac output, cases in need of reoperation are expected to have high mortality rates and less chance of functional recovery 1.

Between September 1992 and May 2014, 47 patients who underwent pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis were retrospectively examined 1. Thirty of the patients were male, the mean age was 45.8 ± 16.7. The cause of constrictive pericarditis was tuberculosis in 22 (46.8 %) patients, idiopathic in 15 (31.9 %), malignancy in 3 (6.4 %), prior cardiac surgery in 2 (4.3 %), non-tuberculosis bacterial infections in 2 (4.3 %), radiotherapy in 1 (2.1 %), uremia in 1 (2.1 %) and post-traumatic in 1 (2.1 %). The surgical approach was achieved via a median sternotomy in all patients except only 1 patient. The mean operative time was 156.4 ± 45.7 min. Improvement in functional status in 80 % of patients’ at least one New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class was observed. In-hospital mortality rate was 2.1 % (1 of 47 patients). The cause of death was pneumonia leading to progressive respiratory failure. The late mortality rate was 23.4 % (11 of 47 patients). The mean follow-up time was 61.2 ± 66 months. The actuarial survival rates were 91 %, 85 % and 81 % at 1, 5 and 10 years, respectively. Recurrence requiring a repeat pericardiectomy was developed in no patient during follow-up.

References- Biçer, M., Özdemir, B., Kan, İ. et al. Long-term outcomes of pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis. J Cardiothorac Surg 10, 177 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-015-0385-8

- Bertog SC, Thambidorai SK, Parakh K, Schoenhagen P, Ozduran V, Houghtaling PL, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(8):1445–52.

- Ling LH, Oh JK, Schaff HV, Danielson GK, Mahoney DW, Seward JB, et al. “Constrictive pericarditis in the modern era: evolving clinical spectrum and impact on outcome after pericardiectomy”. Circulation. 1999;100(no. 13):1380–6.

- [Guideline] Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al, for the ESC Scientific Document Group . 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: The European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7. 36 (42):2921-64.

- [Guideline] Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, Erbel R, Rienmuller R, Adler Y, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. European Society of Cardiology. 2004.

- Vistarini N, Chen C, Mazine A, et al. Pericardiectomy for Constrictive Pericarditis: 20 Years of Experience at the Montreal Heart Institute. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015 Jul. 100 (1):107-13.

- Melo DTP, Nerbass FB, Sayegh ALC, et al. Impact of pericardiectomy on exercise capacity and sleep of patients with chronic constrictive pericarditis. PLoS One. 2019. 14 (10):e0223838

- Clare GC, Troughton RW. Management of constrictive pericarditis in the 21st century. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2007 Dec. 9(6):436-42.