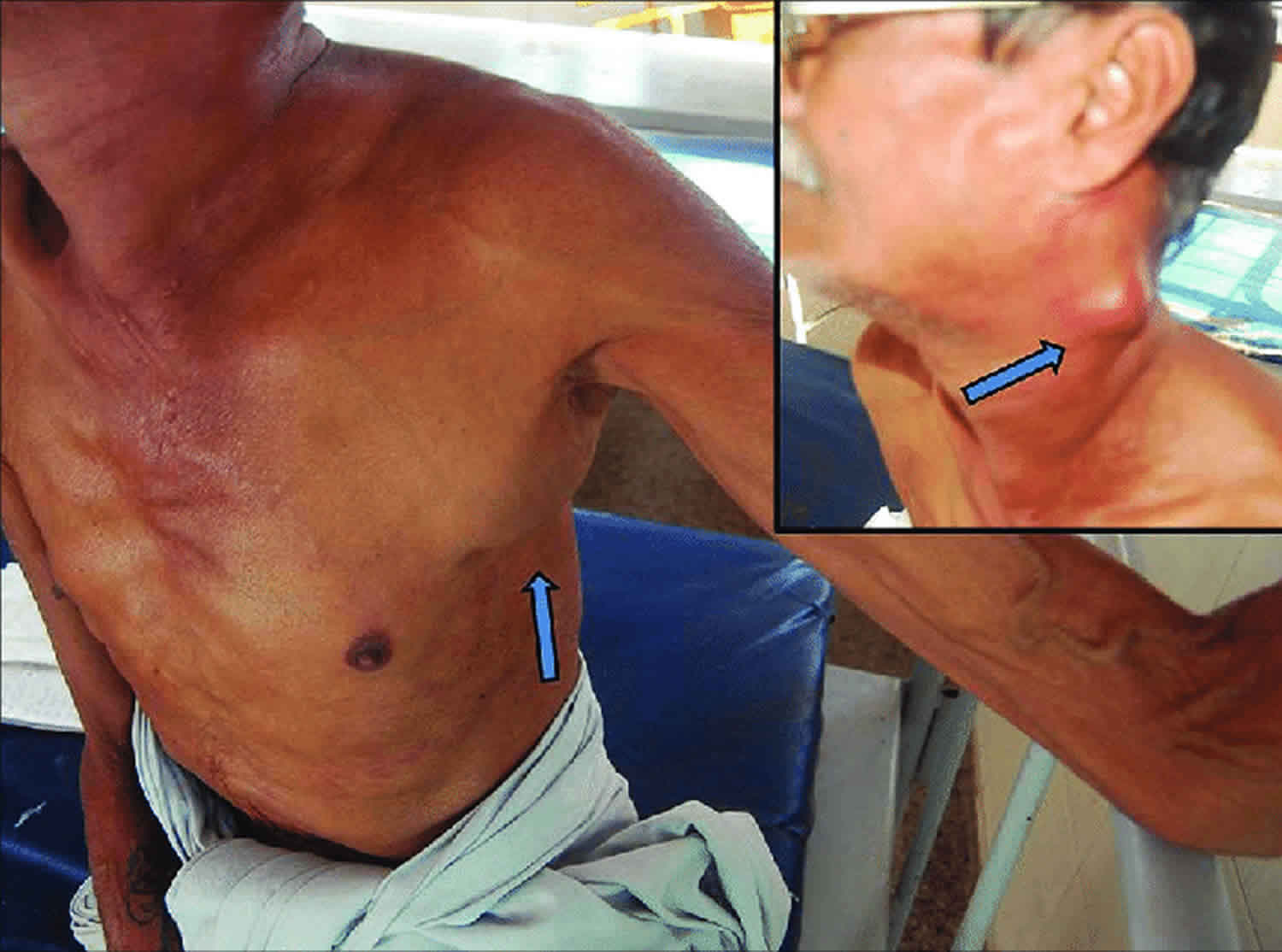

Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy

Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy also known as persistant generalized lymphadenopathy, is defined as painless, non-tender enlarged lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) in at least two areas of the body for at least 3 months, often indicates underlying systemic disease. Lymphadenopathy refers to lymph nodes that are abnormal in size (e.g., greater than 1 cm) or consistency 1. Palpable supraclavicular, popliteal, and iliac lymphadenopathy and epitrochlear lymphadenopathy greater than 5 mm, are considered abnormal. Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy causes include disseminated malignancy, infections and autoimmune diseases, as well as medications and iatrogenic causes. In people with HIV, persistent generalized lymphadenopathy is associated with early stages of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection and with certain opportunistic infections. Acute HIV infection is the phase of HIV disease that occurs immediately after transmission, which is typically characterized by viremia as detected by the presence of HIV RNA or p24 antigen 2. Anti-HIV antibodies are not yet detectable early during this phase of HIV infection. Recent HIV infection is generally considered the phase of HIV disease ≤6 months after infection, during which anti-HIV antibodies develop and become detectable. Throughout this section, the term “early HIV infection” is used to refer to either acute or recent HIV infection. Persons with acute HIV infection may experience fever, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, skin rash, myalgia, arthralgia, and other symptoms; however, illness is generally nonspecific and can be relatively mild or the person can be asymptomatic 3. Clinicians may fail to recognize acute HIV infection because its manifestations are often similar to those of many other viral infections, such as influenza and infectious mononucleosis.

Benign causes of generalized lymphadenopathy are self-limited viral illnesses, such as infectious mononucleosis, and medications. Other causes include activated mycobacterial infection, cryptococcosis, cytomegalovirus, Kaposi sarcoma, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Generalized lymphadenopathy can occur with leukemias, lymphomas, and advanced metastatic carcinomas 4. Risk factors for malignancy include age older than 40 years, male sex, white race, supraclavicular location of the nodes, and presence of systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss. Palpable supraclavicular, popliteal, and iliac lymphadenopathy are abnormal, as are epitrochlear lymphadenopathy greater than 5 mm in diameter 1. The history, physical examination and specific testing is necessary to determine the diagnosis or identify the cause of lymphadenopathy. The workup may include blood tests, imaging, and biopsy depending on clinical presentation, location of the lymphadenopathy, and underlying risk factors. Biopsy options include fine-needle aspiration, core needle biopsy, or open excisional biopsy. Antibiotics may be used to treat acute unilateral cervical lymphadenitis, especially in children with systemic symptoms. Corticosteroids have limited usefulness in the management of unexplained lymphadenopathy and should not be used without an appropriate diagnosis.

What are lymph nodes?

The lymph node functions as an antigen filter for the reticuloendothelial system of the body 5. Lymph node consists of a multi-layered sinus that sequentially exposes B-cell lymphocytes, T-cell lymphocytes, and macrophages to an afferent extracellular fluid. In this way, the immune system can recognize and react to foreign proteins and mount an immune response or sequester these proteins as appropriate. In the course of this reaction, there is some multiplication of the responding immune cell line, and thus, the node itself increases in size. It is generally held that a lymph node size is considered enlarged (lymphadenopathy) when it is larger than 1 cm 5. However, the reality is that “normal” and “enlarged” criteria vary depending on the location of the lymph node and the age of the patient. For example, children younger than 10 years of age have more hypertrophic immune systems and lymph nodes up to 2 cm can be considered normal in some clinical situations yet, an epitrochlear lymph node of above 0.5 cm is considered pathological in an adult 5.

The pattern, distribution, and quality of the lymphadenopathy can provide much clinical information in the diagnostic process. Lymphadenopathy occurs in 2 patterns: generalized and localized. Generalized lymphadenopathy entails lymphadenopathy in 2 or more non-contiguous locations. Localized adenopathy occurs in contiguous groupings of lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are distributed in discrete anatomical areas, and their enlargement reflects the lymphatic drainage of their location. The lymph nodes themselves may be tender or non-tender, fixed or mobile, and discreet or “matted” together. Concomitant symptomatology and the epidemiology of the patient and the illness provide further diagnostic cues. A thorough history of any prodromal illness, fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, and localizing symptoms can be very revealing. Additionally, the demographic particulars of the patient, including age, gender, exposure to infectious disease, toxins, medications, and their habits may provide further cues.

Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy causes

Causes of lymphadenopathy can be remembered with the MIAMI mnemonic: malignancies, infections, autoimmune disorders, miscellaneous and unusual conditions, and iatrogenic causes 6. In most cases, the history and physical examination alone identify the cause. Hard or matted lymph nodes may suggest malignancy or infection. In primary care practice, the annual incidence of unexplained lymphadenopathy is 0.6%.1 Only 1.1% of these cases are related to malignancy, but this percentage increases with advancing age.1 Cancers are identified in 4% of patients 40 years and older who present with unexplained lymphadenopathy vs. 0.4% of those younger than 40 years 7.

Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy causes:

- Malignancies: Kaposi sarcoma, leukemias, lymphomas, metastases, skin neoplasms

- Risk factors for malignancy 8:

- Age older than 40 years

- Duration of lymphadenopathy greater than four to six weeks

- Generalized lymphadenopathy (two or more regions involved)

- Male sex

- Node not returned to baseline after eight to 12 weeks

- Supraclavicular location

- Systemic signs: fever, night sweats, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly

- White race

- Risk factors for malignancy 8:

- Infections:

- Bacterial: brucellosis, cat-scratch disease (Bartonella), chancroid, cutaneous infections (staphylococcal or streptococcal), lymphogranuloma venereum, primary and secondary syphilis, tuberculosis, tularemia, typhoid fever

- Granulomatous: berylliosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, silicosis

- Viral: adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis, herpes zoster, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), infectious mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus), rubella

- Other: fungal, helminthic, Lyme disease, rickettsial, scrub typhus, toxoplasmosis

- Autoimmune disorders: Dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, Still disease, systemic lupus erythematosus

- Miscellaneous/unusual conditions: Angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman disease), histiocytosis, Kawasaki disease, Kikuchi lymphadenitis, Kimura disease, sarcoidosis

- Iatrogenic causes: Medications, serum sickness

- Medications that can cause lymphadenopathy 9:

- Allopurinol

- Atenolol

- Captopril

- Carbamazepine (Tegretol)

- Gold

- Hydralazine

- Penicillins

- Phenytoin (Dilantin)

- Primidone (Mysoline)

- Pyrimethamine (Daraprim)

- Quinidine

- Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

- Sulindac

- Medications that can cause lymphadenopathy 9:

Factors that can assist in identifying the cause of lymphadenopathy include patient age, duration of lymphadenopathy, exposures, associated symptoms, and location (localized vs. generalized). Table 1 lists common historical clues and their associated diagnoses 6. Other historical questions include asking about time course of enlargement, tenderness to palpation, recent infections, recent immunizations, and medications 8.

Age and duration

About one-half of otherwise healthy children have palpable lymph nodes at any one time 8. Most lymphadenopathy in children is benign or infectious in etiology. In adults and children, lymphadenopathy lasting less than two weeks or greater than 12 months without change in size has a low likelihood of being neoplastic 6. Exceptions include low-grade Hodgkin lymphomas and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, although both typically have associated systemic symptoms 10.

Exposures

Environmental, travel-related, animal, and insect exposures should be ascertained. Chronic medication use, infectious exposures, immunization status, and recent immunizations should be reviewed as well. Tobacco and alcohol use and ultraviolet radiation exposure increase concerns for neoplasm. An occupational history that includes mining, masonry, and metal work may elicit work-related causes of lymphadenopathy, such as silicon or beryllium exposure. Asking about sexual history to assess exposure to genital sores or participation in oral intercourse is important, especially for inguinal and cervical lymphadenopathy. Finally, family history may identify familial causes of lymphadenopathy, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome or lipid storage diseases 6.

Associated symptoms

A thorough review of systems aids in identifying any red flag symptoms.

Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy symptoms

Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy symptoms depend on the underlying cause. Arthralgias, muscle weakness, and rash suggest an autoimmune etiology. Constitutional symptoms of fever, chills, fatigue, and malaise indicate an infectious etiology. In addition to fever, drenching night sweats and unexplained weight loss of greater than 10% of body weight may suggest Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma 10.

Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy diagnosis

Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy is diagnosed clinically. Lymph node biopsy is not indicated in patients with early-stage HIV disease unless the patient has signs and symptoms of systemic illness (eg, fever, weight loss) or enlarged, fixed, or coalescent lymph nodes. A serologic diagnosis of acute Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or cytomegalovirus (CMV) mononucleosis should be considered.

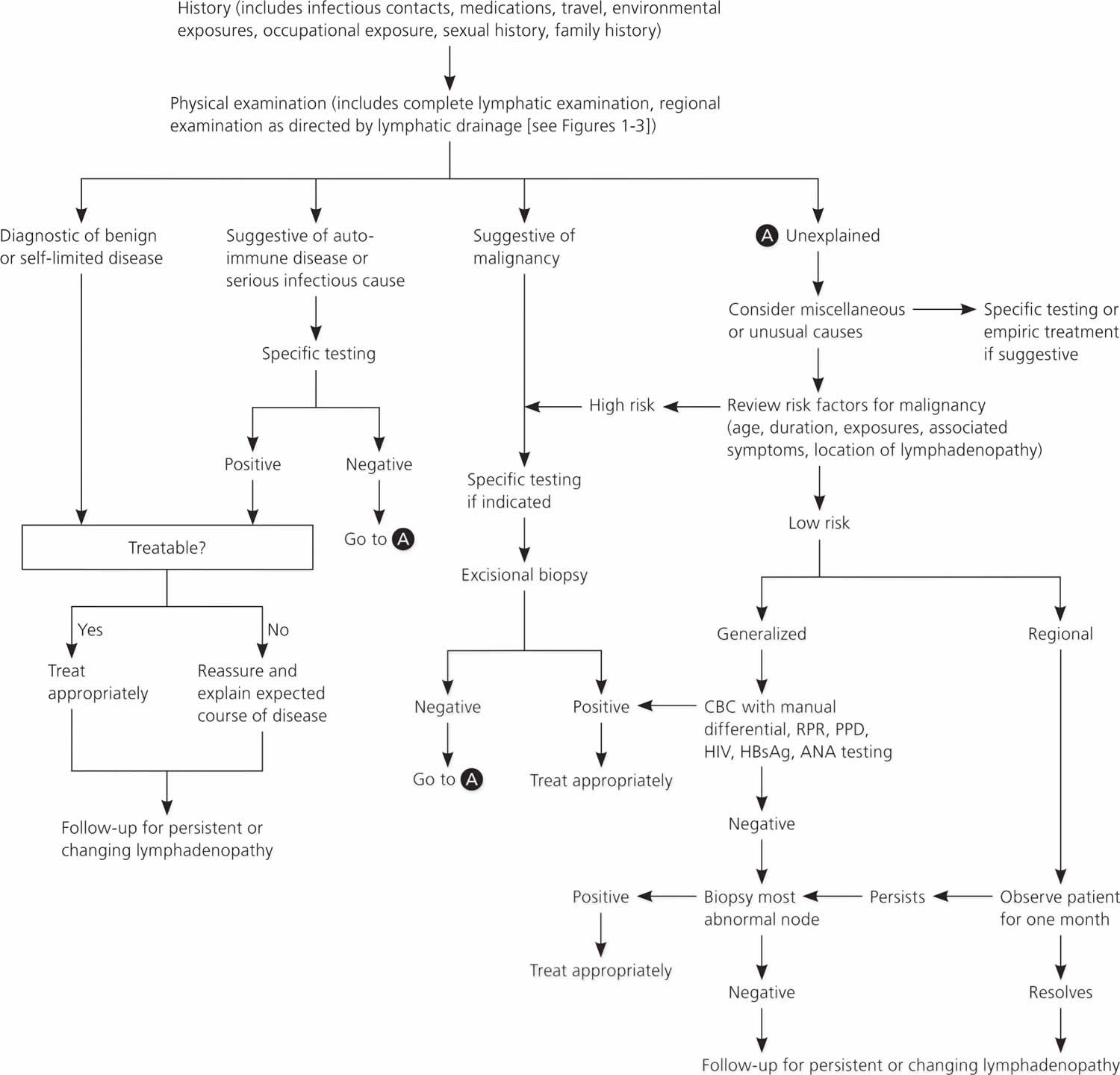

Figure 1 provides an algorithm for evaluating lymphadenopathy 6. If history and physical examination findings suggest a benign or self-limited process, reassurance can be provided and follow-up arranged if lymphadenopathy persists. Findings suggestive of infectious or autoimmune etiologies may require specific testing and treatment as indicated. If malignancy is considered unlikely based on history and physical examination, localized lymphadenopathy can be observed for four weeks. Generalized lymphadenopathy should prompt routine laboratory testing and testing for autoimmune and infectious causes 6.

Patients with suspected acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection should undergo serum testing for HIV antibody and HIV antigen using HIV nucleic acid amplification, HIV p24 antigen, fourth-generation enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) (antibody and antigen), or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for viral load. Beware of false-positive HIV viral load test results (< 15,000 RNA copies/mL blood) 11.

Figure 1. Algorithm for evaluating lymphadenopathy

Abbreviations: ANA = antinuclear antibody; CBC = complete blood count; HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen; HIV = human immunodeficienty virus; PPD = purified protein derivative; RPR = rapid plasma reagin

[Source 12 ]Table 1. Clues and initial testing to determine the cause of lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes)

| Historical clues | Suggested diagnoses | Initial testing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fever, night sweats, weight loss, or node located in supraclavicular, popliteal, or iliac region, bruising, splenomegaly | Leukemia, lymphoma, solid tumor metastasis | Complete blood count, nodal biopsy or bone marrow biopsy; imaging with ultrasonography or computed tomography may be considered but should not delay referral for biopsy | |

| Fever, chills, malaise, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea; no other red flag symptoms | Bacterial or viral pharyngitis, hepatitis, influenza, mononucleosis, tuberculosis (if exposed), rubella | Limited illnesses may not require any additional testing; depending on clinical assessment, consider complete blood count, monospot test, liver function tests, cultures, and disease-specific serologies as needed | |

| High-risk sexual behavior | Chancroid, HIV infection, lymphogranuloma venereum, syphilis | HIV-1/HIV-2 immunoassay, rapid plasma reagin, culture of lesions, nucleic acid amplification for chlamydia, migration inhibitory factor test | |

| Animal or food contact | |||

| Cats | Cat-scratch disease Bartonella | Serology and polymerase chain reaction | |

| Toxoplasmosis | Serology | ||

| Rabbits, or sheep or cattle wool, hair, or hides | Anthrax | Per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines | |

| Brucellosis | Serology and polymerase chain reaction | ||

| Tularemia | Blood culture and serology | ||

| Undercooked meat | Anthrax | Per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines | |

| Brucellosis | Serology and polymerase chain reaction | ||

| Toxoplasmosis | Serology | ||

| Recent travel, insect bites | Diagnoses based on endemic region | Serology and testing as indicated by suspected exposure | |

| Arthralgias, rash, joint stiffness, fever, chills, muscle weakness | Rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, dermatomyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus | Antinuclear antibody, anti-doubled-stranded DNA, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, complete blood count, rheumatoid factor, creatine kinase, electromyography, or muscle biopsy as indicated | |

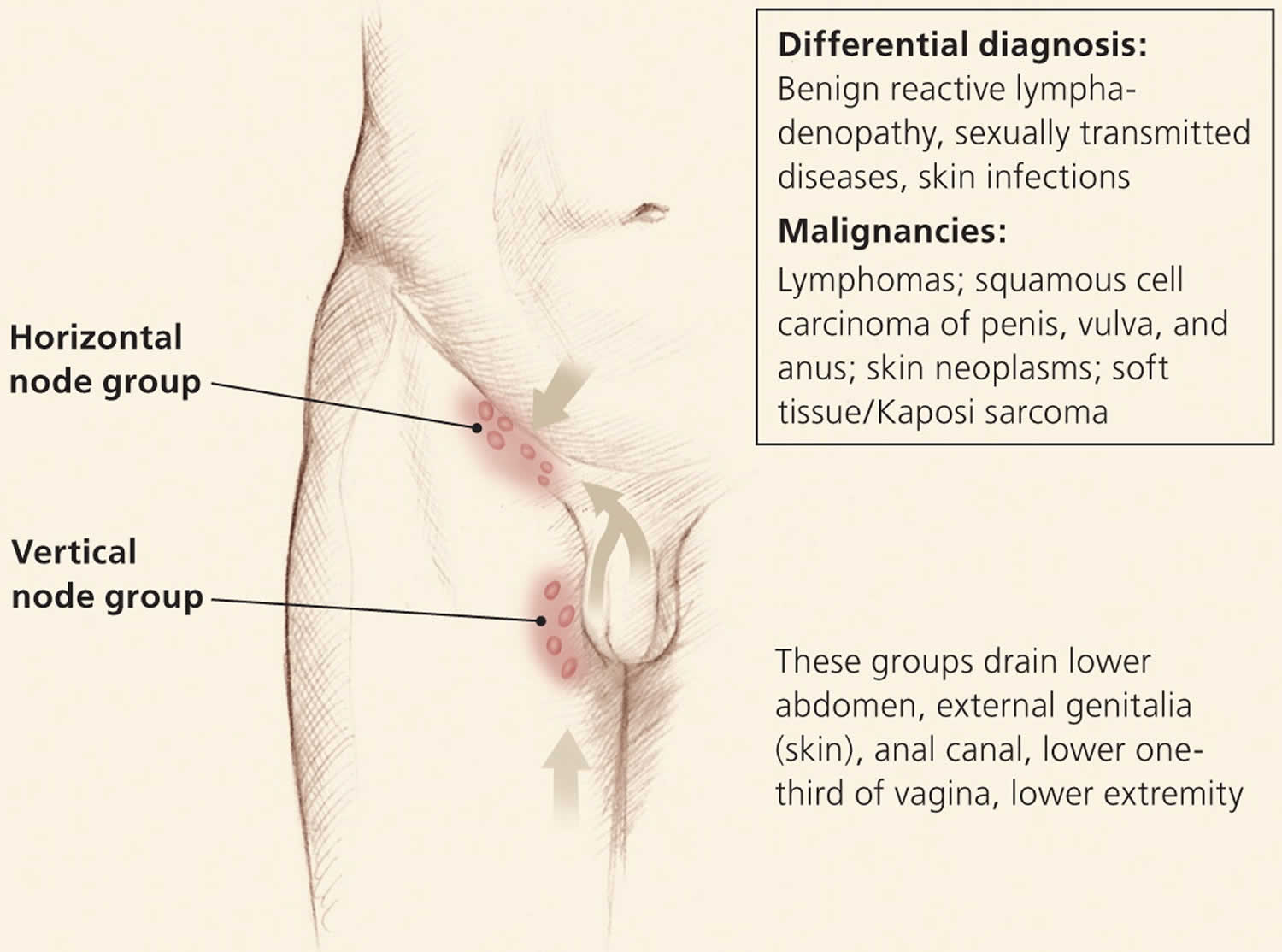

Physical examination

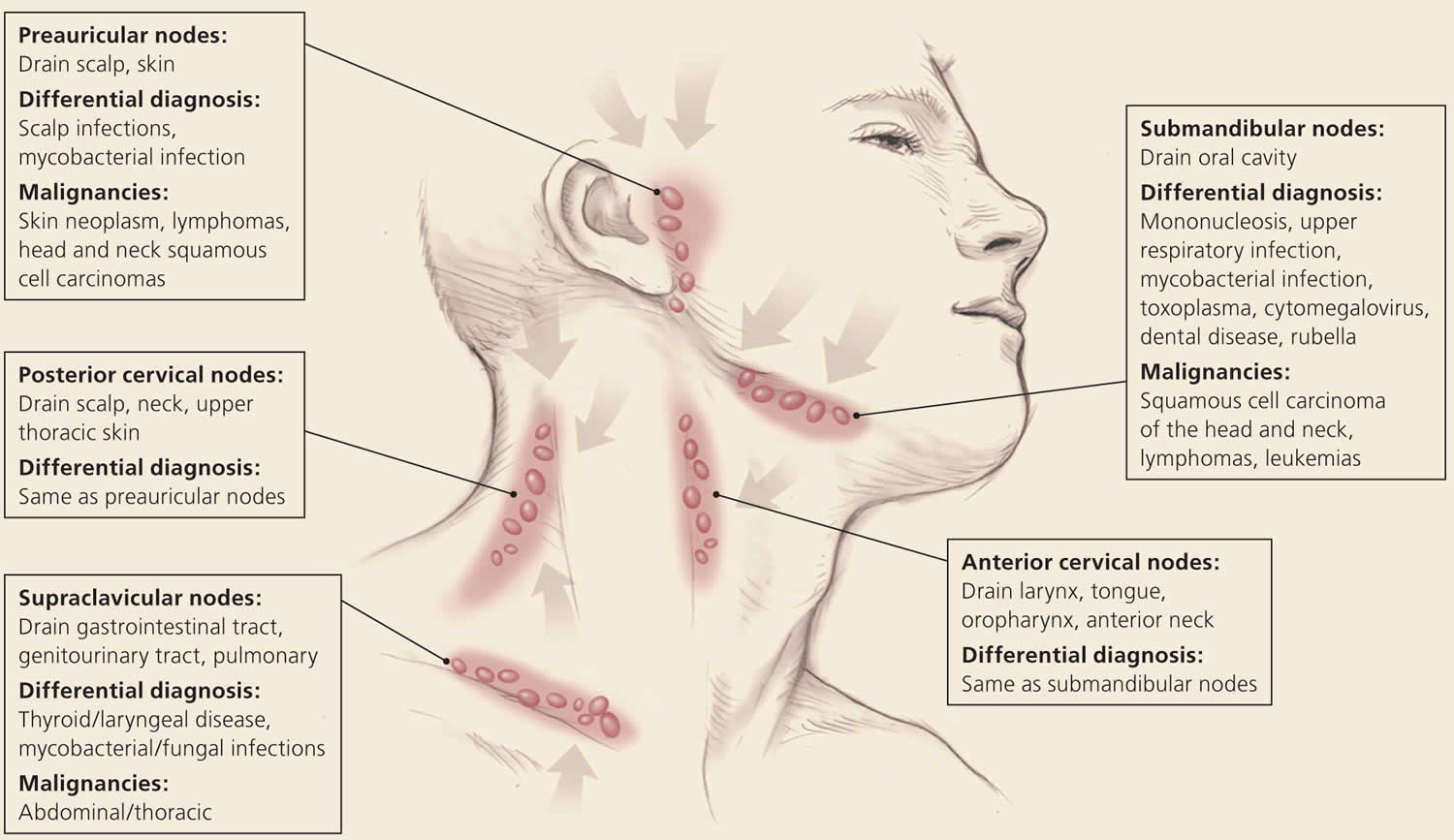

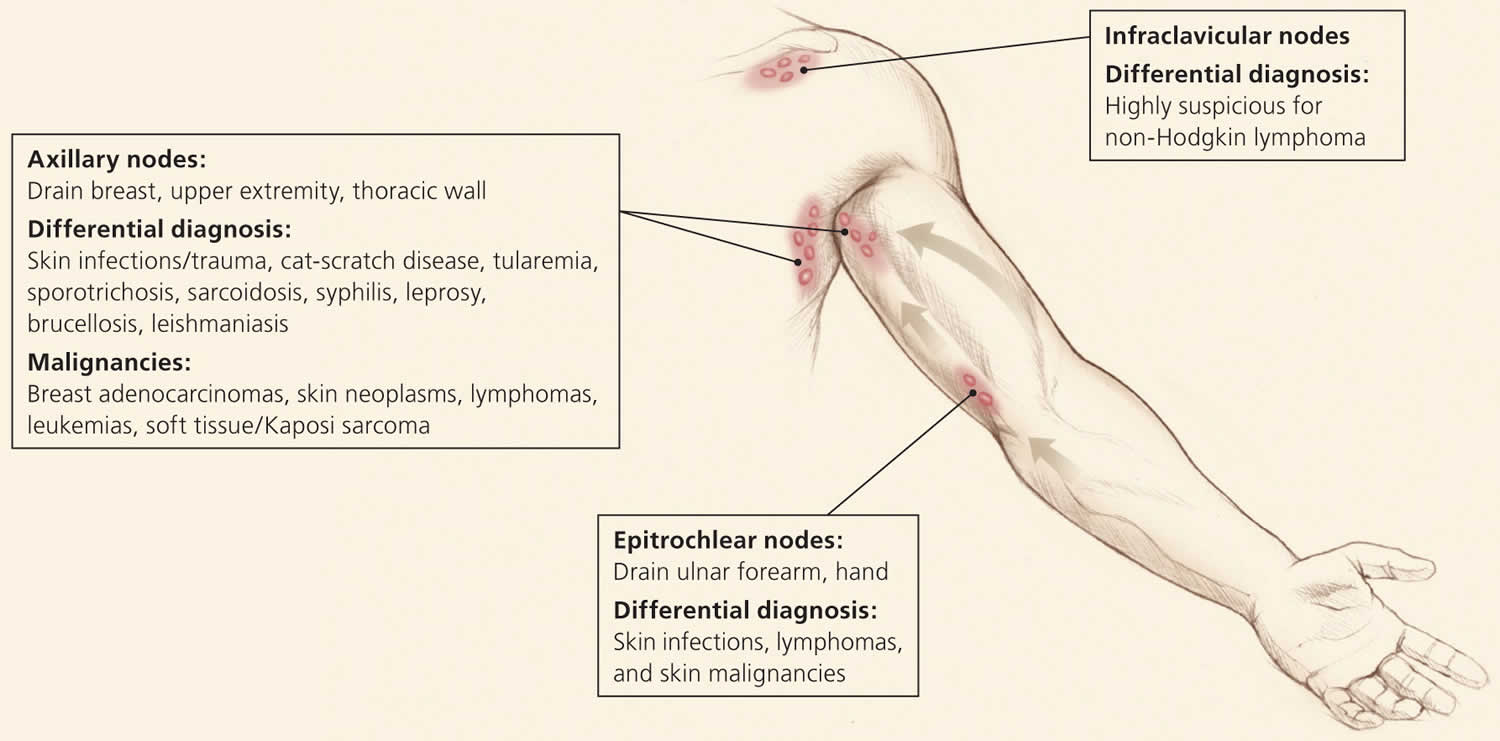

Overall state of health and height and weight measurements may help identify signs of chronic disease, especially in children 13. A complete lymphatic examination should be performed to rule out generalized lymphadenopathy, followed by a focused lymphatic examination with consideration of lymphatic drainage patterns. Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4 demonstrate typical lymphatic drainage patterns, as well as common causes of lymphadenopathy in these regions 6. A skin examination should be performed to rule out other lesions that would point to malignancy and to evaluate for erythematous lines along nodal tracts or any trauma that could lead to an infectious source of the lymphadenopathy. Finally, abdominal examination focused on splenomegaly, although rarely associated with lymphadenopathy, may be useful for detecting infectious mononucleosis, lymphocytic leukemias, lymphoma, or sarcoidosis 6.

Figure 1. Lymph nodes of the head and neck and the regions that they drain

Figure 2. Axillary lymphatics and the structures that they drain

Figure 3. Inguinal lymphatics and the structures that they drain

Lymph node character and size

The quality and size of lymph nodes should be assessed. Lymph node qualities include warmth, overlying erythema, tenderness, mobility, fluctuance, and consistency. Shotty lymphadenopathy is the presence of multiple small lymph nodes that feel like “buck shots” under the skin 14. This usually implies reactive lymphadenopathy from viral infection. A painless, hard, irregular mass or a firm, rubbery lesion that is immobile or fixed may represent a malignancy, although in general, qualitative characteristics are unable to reliably predict malignancy. Painful or tender lymphadenopathy is nonspecific and may represent possible inflammation caused by infection, but it can also be the result of hemorrhage into a node or necrosis 4. No specific nodal size is indicative of malignancy 4.

Imaging studies

Radiologic evaluation with computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasonography may help to characterize lymphadenopathy. The American College of Radiology recommends ultrasonography as the initial imaging choice for cervical lymphadenopathy in children up to 14 years of age and computed tomography for persons older than 14 years 15. Based on the location of the abnormal nodes, the sensitivity of these modalities for diagnosing metastatic lymph nodes varies; therefore, history and clinical examination must guide selection 16. If the diagnosis is still uncertain, biopsy is recommended.

In children with acute unilateral anterior cervical lymphadenitis and systemic symptoms, antibiotics may be prescribed. Empiric antibiotics should target Staphylococcus aureus and group A streptococci. Options include oral cephalosporins, amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin), orclindamycin 17. Corticosteroids should be avoided until a definitive diagnosis is made because treatment could potentially mask or delay histologic diagnosis of leukemia or lymphoma 18.

Lymph node biopsy

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy can aid in the diagnostic evaluation of lymph nodes when cause is unknown or malignant risk factors are present. FNA cytology is a quick, accurate, minimally invasive, and safe technique to evaluate patients and aid in triage of unexplained lymphadenopathy 19. If a reactive lymph node is likely, core needle biopsy can be avoided, and FNA used alone. Combined, they allow cytologic and histopathologic assessment of lymph nodes. However, the use of both techniques may not be needed because the diagnostic accuracy of FNA in adult populations has been reported to approach 90%, with a sensitivity and specificity of 85% to 95% and 98% to 100%, respectively 20. False-positive diagnoses are rare with FNA. False-negative results occur secondary to early or partial involvement of lymph nodes, inexperience with lymph node cytology, unrecognized lymphomas with heterogeneity, and sampling errors 21. There are concerns about the reliability of FNA in the diagnosis of diseases such as lymphoma because it is unable to assess lymph node architecture. Regardless, FNA may be a useful triage tool for differentiating benign reactive lymphadenopathy from malignancy 22.

Open excisional biopsy remains a diagnostic option for patients who do not wish to undergo additional procedures. When selecting nodes for any method, the largest, most suspicious, and most accessible node should be sampled. Inguinal nodes typically display the lowest yield, and supraclavicular nodes have the highest 23.

Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy treatment

Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy treatment involves treating the underlying cause.

Treatment of acute and recent (early) HIV infection

- Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is recommended for all individuals with HIV, including those with early HIV infection. ART should be initiated as soon as possible after HIV diagnosis (AII).

- The goal of ART is to suppress plasma HIV RNA to undetectable levels and to prevent transmission of HIV. Testing for plasma HIV RNA levels, CD4 T lymphocyte cell counts, and toxicity monitoring should be performed as recommended for persons with chronic HIV infection.

- A sample for genotypic testing should be sent before initiation of ART. ART can be initiated before drug resistance testing and HLA B*5701 test results are available. In this setting, one of the following ART regimens is recommended:

- Bictegravir (BIC)/tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)/emtricitabine (FTC)

- Dolutegravir (DTG) with (tenofovir alafenamide [TAF] or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [TDF]) plus (emtricitabine [FTC] or lamivudine [3TC])

- Boosted darunavir (DRV) with (tenofovir alafenamide [TAF] or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [TDF]) plus (emtricitabine [FTC] or lamivudine [3TC])

- Pregnancy testing should be performed in individuals of childbearing potential before initiation of ART.

- Data from an observational study in Botswana suggest there may be an increased risk of neural tube defects in infants born to individuals who were receiving Dolutegravir (DTG) at the time of conception 24. Before initiating an integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based regimen in a person of childbearing potential, clinicians should review information to consider when choosing an ART regimen.

- As there are no safety data for Bictegravir (BIC) use around the time of conception, an approach similar to that outlined for Dolutegravir (DTG) should be considered for Bictegravir (BIC)-containing ART.

- When the results of drug resistance and HLA-B*5701 testing are available, the treatment regimen can be modified if needed.

- Doctors should inform individuals starting ART of the importance of adherence to achieve and maintain viral suppression.

The goal of ART during early HIV infection is to suppress plasma HIV RNA to undetectable levels and to prevent the transmission of HIV. Importantly, as with chronic HIV infection, persons with early HIV infection must be willing and able to commit to life-long ART. Individuals who do not begin ART immediately should be maintained in care and every effort made to initiate therapy as soon as they are ready.

Clinical trial data regarding the treatment of early HIV infection are limited. However, a number of studies suggest that individuals who are treated during early infection may experience immunologic and virologic benefits 25. In addition, early HIV infection is often associated with high viral loads and increased infectiousness 26 and the use of ART at this stage of infection to achieve and maintain a viral load <200 copies/mL is expected to substantially reduce the risk of HIV transmission 27.

The START 28 and TEMPRANO 29 trials evaluated the timing of ART initiation. Although neither trial collected specific information on participants with early infection, the strength of the overall results from both studies’ and the evidence from the other studies described above strongly suggest that, whenever possible, persons with HIV should begin ART upon diagnosis of early infection.

References- Unexplained Lymphadenopathy: Evaluation and Differential Diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Dec 1;94(11):896-903. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2016/1201/p896.html

- Acute and Recent (Early) HIV Infection. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arv/20/acute-and-recent–early–hiv-infection

- Hoenigl M, Green N, Camacho M, et al. Signs or Symptoms of Acute HIV Infection in a Cohort Undergoing Community-Based Screening. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(3):532-534. doi:10.3201/eid2203.151607

- Habermann TM, Steensma DP. Lymphadenopathy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75(7):723–732.

- Freeman AM, Matto P. Adenopathy. [Updated 2019 Nov 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513250

- Bazemore AW, Smucker DR. Lymphadenopathy and malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(11):2103–2110.

- Fijten GH, Blijham GH. Unexplained lymphadenopathy in family practice. An evaluation of the probability of malignant causes and the effectiveness of physicians’ workup. J Fam Pract. 1988;27(4):373–376.

- King D, Ramachandra J, Yeomanson D. Lymphadenopathy in children: refer or reassure? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2014;99(3):101–110.

- Bazemore AW, Smucker DR. Lymphadenopathy and malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(11):2108.

- Salzman BE, Lamb K, Olszewski RF, Tully A, Studdiford J. Diagnosing cancer in the symptomatic patient. Prim Care. 2009;36(4):651–670.

- Pilcher CD, Fiscus SA, Nguyen TQ, Foust E, Wolf L, Williams D. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. N Engl J Med. 2005 May 5. 352(18):1873-83.

- Bazemore AW, Smucker DR. Lymphadenopathy and malignancy. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(11):2109.

- Rajasekaran K, Krakovitz P. Enlarged neck lymph nodes in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(4):923–936.

- Ferrer R. Lymphadenopathy: differential diagnosis and evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(6):1313–1320.

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria: neck mass/adenopathy. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69504/Narrative

- Dudea SM, Lenghel M, Botar-Jid C, Vasilescu D, Duma M. Ultrasonography of superficial lymph nodes: benign vs. malignant. Med Ultrason. 2012;14(4):294–306.

- Meier JD, Grimmer JF. Evaluation and management of neck masses in children. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(5):353–358.

- Pangalis GA, Vassilakopoulos TP, Boussiotis VA, Fessas P. Clinical approach to lymphadenopathy. Semin Oncol. 1993;20(6):570–582.

- Monaco SE, Khalbuss WE, Pantanowitz L. Benign non-infectious causes of lymphadenopathy: a review of cytomorphology and differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40(10):925–938.

- Lioe TF, Elliott H, Allen DC, Spence RA. The role of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the investigation of superficial lymphadenopathy; uses and limitations of the technique. Cytopathology. 1999;10(5):291–297.

- Thomas JO, Adeyi D, Amanguno H. Fine-needle aspiration in the management of peripheral lymphadenopathy in a developing country. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21(3):159–162.

- Metzgeroth G, Schneider S, Walz C, et al. Fine needle aspiration and core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of lymphadenopathy of unknown aetiology. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(9):1477–1484.

- Karadeniz C, Oguz A, Ezer U, Oztürk G, Dursun A. The etiology of peripheral lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;16(6):525–531.

- Zash R, Makhema J, Shapiro RL. Neural-Tube Defects with Dolutegravir Treatment from the Time of Conception. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(10):979-981. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1807653 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6550482

- Ananworanich J, Chomont N, Eller LA, et al. HIV DNA Set Point is Rapidly Established in Acute HIV Infection and Dramatically Reduced by Early ART. EBioMedicine. 2016;11:68-72. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.07.024

- Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(9):1403-1409. doi:10.1086/429411

- Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2428-2438. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30418-0

- INSIGHT START Study Group, Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, et al. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506816

- TEMPRANO ANRS 12136 Study Group, Danel C, Moh R, et al. A Trial of Early Antiretrovirals and Isoniazid Preventive Therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):808-822. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1507198