Pitt Hopkins syndrome

Pitt Hopkins syndrome is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by intellectual disability and developmental delay, breathing problems, recurrent seizures (epilepsy), and distinctive facial features 1. People with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome have moderate to severe intellectual disability. Most affected individuals have delayed development of mental and motor skills (psychomotor delay). They are delayed in learning to walk and developing fine motor skills such as picking up small items with their fingers. People with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome typically do not develop speech; some may learn to say a few words. Many affected individuals exhibit features of autistic spectrum disorders, which are characterized by impaired communication and socialization skills.

Breathing problems in individuals with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome are characterized by episodes of rapid breathing (hyperventilation) followed by periods in which breathing slows or stops (apnea). These episodes can cause a lack of oxygen in the blood, leading to a bluish appearance of the skin or lips (cyanosis). In some cases, the lack of oxygen can cause loss of consciousness. Some older individuals with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome develop widened and rounded tips of the fingers and toes (clubbing) because of recurrent episodes of decreased oxygen in the blood. The breathing problems occur only when the person is awake and typically first appear in mid-childhood, but they can begin as early as infancy. Episodes of hyperventilation and apnea can be triggered by emotions such as excitement or anxiety or by extreme tiredness (fatigue).

Epilepsy occurs in most people with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome and usually begins during childhood, although it can be present from birth.

Individuals with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome have distinctive facial features that include thin eyebrows, sunken eyes, a prominent nose with a high nasal bridge, a pronounced double curve of the upper lip (Cupid’s bow), a wide mouth with full lips, and widely spaced teeth. The ears are usually thick and cup-shaped.

Children with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome typically have a happy, excitable demeanor with frequent smiling, laughter, and hand-flapping movements. However, they can also experience anxiety and behavioral problems.

Other features of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome may include constipation and other gastrointestinal problems, an unusually small head (microcephaly), nearsightedness (myopia), eyes that do not look in the same direction (strabismus), short stature, and minor brain abnormalities. Affected individuals may also have small hands and feet, a single crease across the palms of the hands, flat feet (pes planus), or unusually fleshy pads at the tips of the fingers and toes. Males with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome may have undescended testes (cryptorchidism).

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome affects both males and females and can affect individuals of any ethnic or racial background. The exact incidence of the disorder is unknown. Approximately 500 affected individuals have been identified worldwide. Researchers believe that affected individuals often go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, making it difficult to determine the true frequency the disorder in the general population. Intellectual disability (due to all causes) affects approximately 1%-3% of the general population.

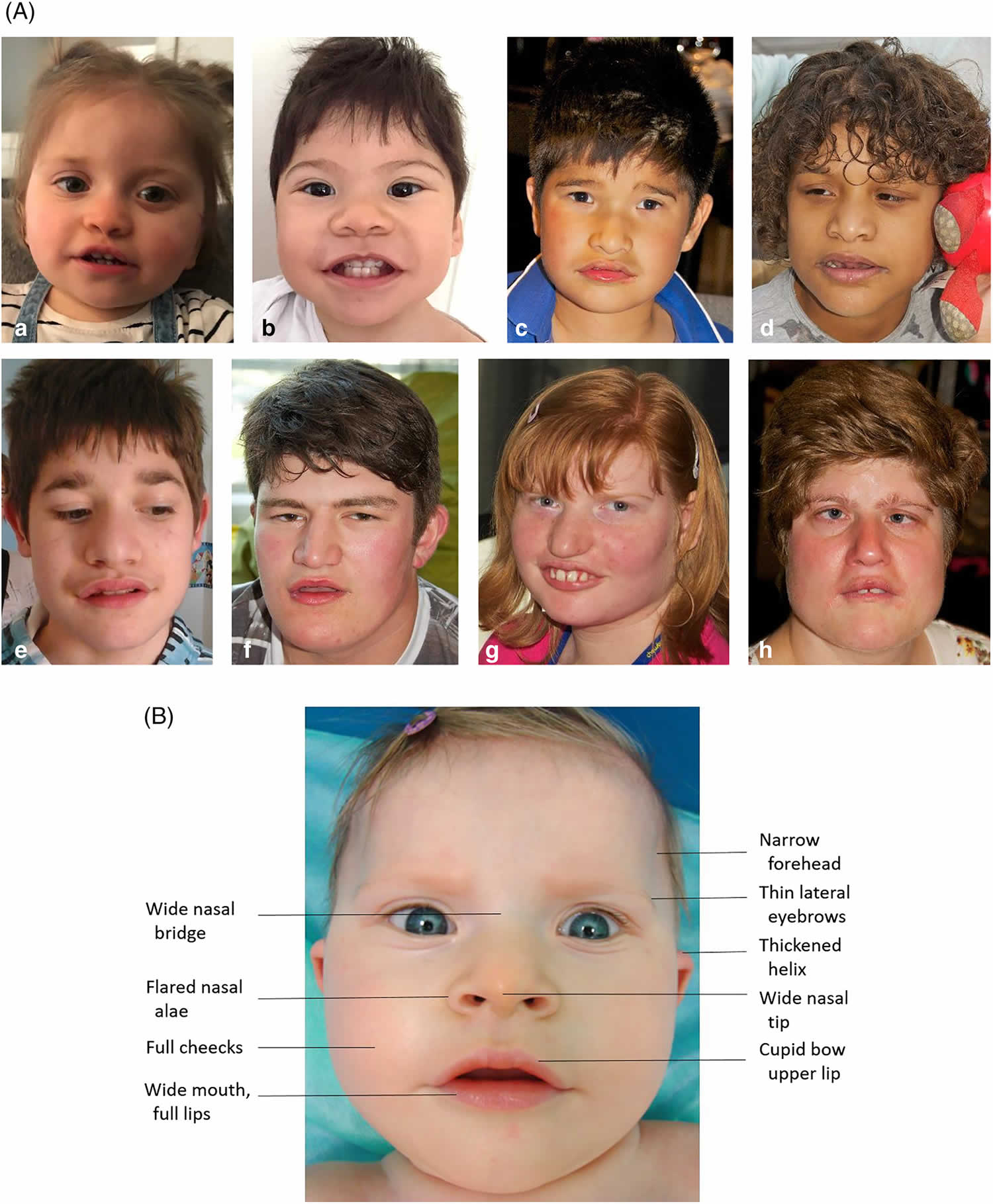

Figure 1. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome

Footnote: Photographs demonstrating the facial gestalt commonly seen in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: broad nasal bridge with bulbous tip, wide mouth with Cupid’s bow philtrum, and prominent ears. Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome is commonly described to have certain characteristic facial features (89%) described as “coarse” with up-slanted palpebral fissures, beaked nasal bridge, prominent ears, and a broad mouth with exaggerated “Cupid’s Bow” appearance of the philtrum. A single palmar crease (60%), persistent fetal finger pads (45%), post-natal growth restriction including short stature (38%) and microcephaly (59%) are also commonly seen 2. Other finger and toe anomalies including over-riding toes, syndactyly, and polydactyly have also been described (53%). Less commonly, clubbing (19%) and scoliosis (20%) are described. Figure 1 depicts the facial features. Figure 2 for graphical representation of these rates of commonly reported dysmorphic features and Figure 3 depicts fetal pads, flat feet, and overriding toes that were seen in our cohort.

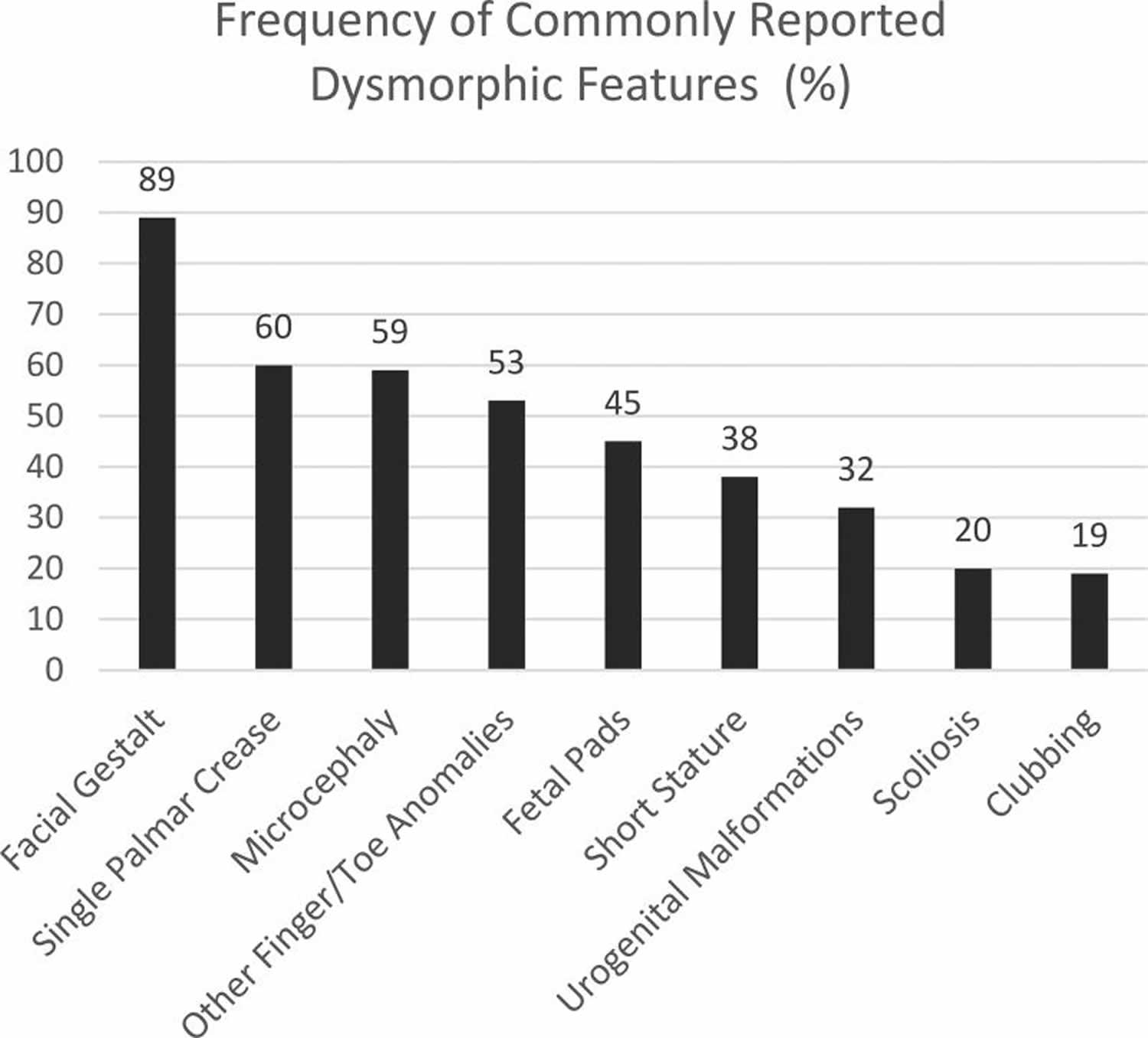

[Source 3 ]Figure 2. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome commonly reported dysmorphic characteristics

Footnote: Graph depicting the rates of commonly reported dysmorphic characteristics as reported in the published cases.

[Source 4 ]Figure 3. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome fetal pads, flat feet and overriding toes

[Source 4 ]Figure 4. Facial features of patients with TCF4-related Pitt-Hopkins syndrome

Footnote: Patient 1 in A (6 months), B (18 months) and C (14 years). Patient 6 in D and H (29 years). Patient 2 in E , F (6 months) and G (11 years). Patient 3 in I (3 years), J (6 years) and K (8.75 years). Patient 4 in L and M (12.5 years). Note the deep-set eyes, broad and beaked nasal bridge with down-turned, pointed nasal tip, and flaring nostrils; the wide mouth with widely spaced teeth, and Cupid-bowed and everted lower lip; the mildly cup-shaped, fleshy ears; as well as increased coarsening of the facial features with age.

[Source 5 ]Figure 5. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome is due to a splice-cite mutation in the TCF4 gene

Footnote: The boy’s Pitt-Hopkins syndrome is due to a splice-cite mutation in the TCF4 gene. In photo 1, he is half-a-year old, in photos 2–4 three years old, and in photo 5 five years old. Note the broad nose, flared and anteverted nostrils, protruding philtrum, large mouth, bow-shape upper lip, broad lips, broad ear helices, and the development of myopia by the age of 5.

[Source 5 ]Pitt-Hopkins-like syndrome

Pitt-Hopkins-like syndrome is a rare, genetic, syndromic intellectual disability disorder characterized by severe intellectual disability, lack of speech with normal, or mildly delayed, motor development, episodic breathing abnormalities, early-onset seizures and facial dysmorphism which only includes a wide mouth 6. Abnormal sleep-wake cycles, autistic behavior and stereotypic movements are commonly associated.

Pitt Hopkins syndrome causes

Mutations in the TCF4 gene cause Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Investigators have determined that the TCF4 gene is located on the long arm (q) of chromosome 18 (18q21.2). Each chromosome has a short arm designated “p” and a long arm designated “q”. Chromosomes are further sub-divided into many bands that are numbered. For example, “chromosome 18q21.2” refers to band 21.2 on the long arm of chromosome 18. The numbered bands specify the location of the thousands of genes that are present on each chromosome. TCF4 gene provides instructions for making a protein that attaches (binds) to other proteins and then binds to specific regions of DNA to help control the activity of many other genes. On the basis of its DNA binding and gene controlling activities, the TCF4 protein is known as a transcription factor. The TCF4 protein plays a role in the maturation of cells to carry out specific functions (cell differentiation) and the self-destruction of cells (apoptosis).

TCF4 gene mutations disrupt the protein’s ability to bind to DNA and control the activity of certain genes. These disruptions, particularly the inability of the TCF4 protein to control the activity of genes involved in nervous system development and function, contribute to the signs and symptoms of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Furthermore, additional proteins interact with the TCF4 protein to carry out specific functions. When the TCF4 protein is nonfunctional, these other proteins are also unable to function normally. It is also likely that the loss of the normal proteins that are attached to the nonfunctional TCF4 proteins contribute to the features of this condition. The loss of one protein in particular, the ASCL1 protein, is thought to be associated with breathing problems in people with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome.

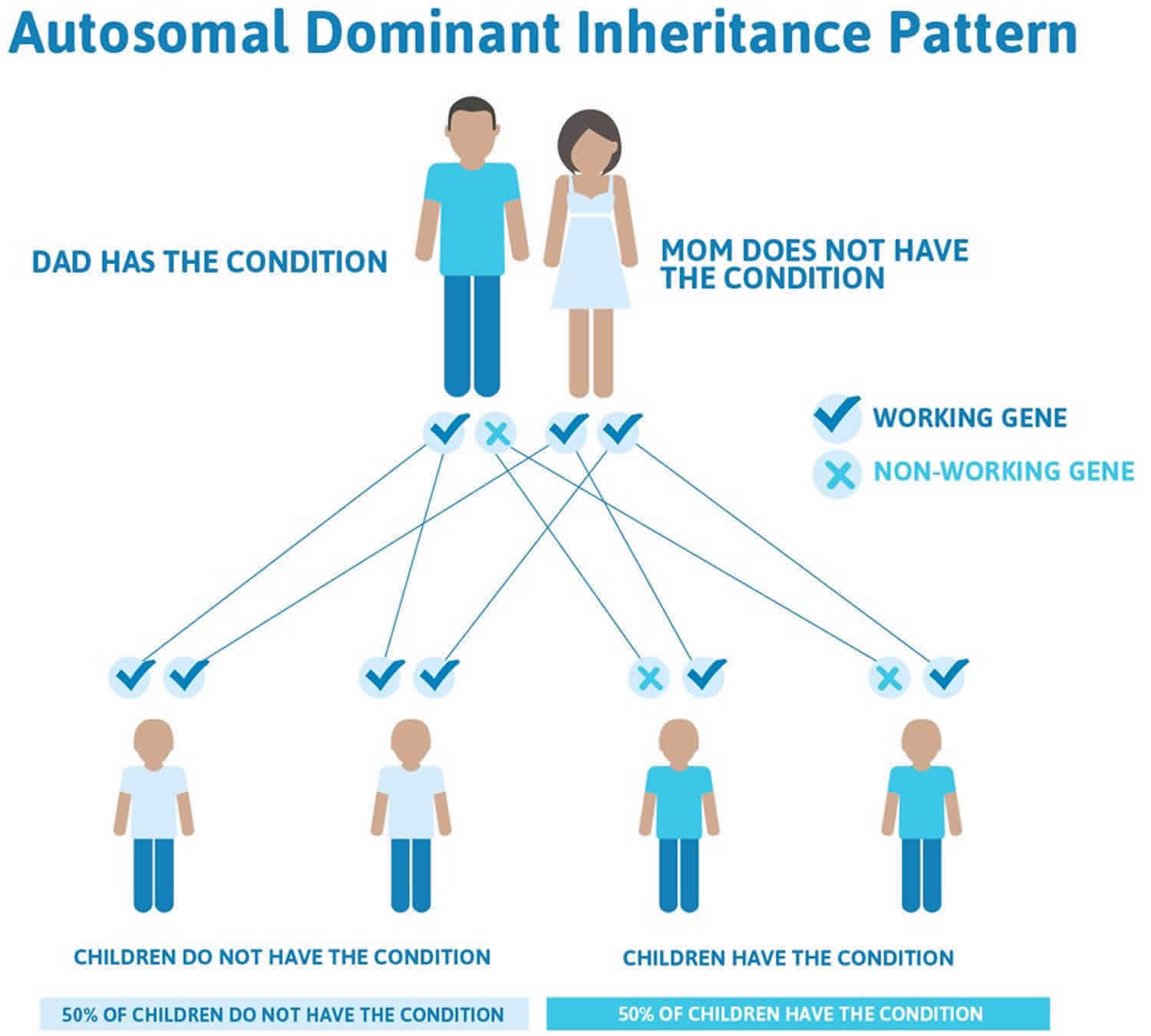

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome inheritance pattern

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder.

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome is caused by haploinsufficiency of TCF4 resulting from either a pathogenic variant in TCF4 or a deletion of the chromosome region in which TCF4 is located (18q21.2) 7. Most affected individuals have been simplex cases (i.e., a single occurrence in a family) resulting from a de novo pathogenic variant or deletion. The risk to sibs of a proband is low, but higher than that of the general population because of the possibility of parental germline mosaicism. Once the Pitt-Hopkins syndrome-related genetic alteration has been identified in an affected family member, prenatal testing for a pregnancy at increased risk and preimplantation genetic diagnosis are possible.

There are several instances in which an unaffected parent has more than one child with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. This extremely rare event occurred because of germline mosaicism. In germline mosaicism, one parent has some reproductive cells (germ cells) in the ovaries or testes that have the TCF4 gene mutation. The other cells in the parent’s body do not have the mutation, so these parents are unaffected but can pass an altered gene to their children. Because of this possibility, scientists estimate parents of a child with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome have about a 1-2% chance of having another affected child, even if the parents test negative for the mutation in their blood.

Figure 6. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Pitt Hopkins syndrome symptoms

With the publication of an increasing number of case series scientists are developing a better picture of associated symptoms and prognosis of individuals with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. However, much about the disorder is not fully understood. It is important to note that affected individuals may not have all of the symptoms discussed below. Parents should talk to their children’s physician and medical team about their specific case, associated symptoms and overall prognosis.

Pediatric Pitt Hopkins Syndrome signs and symptoms:

- Abnormal craniofacial features including a small head circumference; a receding forehead; broad nose; a broad, cupid-shaped mouth; and prominent ears.

- Low muscle tone which can affect feeding in infancy and motor development later, including difficulty with walking and balance.

- Breathing problems including periods of fast breathing followed by no breathing that slows or stops. Typically, children with this condition exhibit no breathing problems when they are asleep.

- Constipation and other gastrointestinal problems.

- Seizures including recurrent seizures that can be present from birth.

- Behavioral issues ranging from hyperactivity to aggression.

- Developmental problems including delayed development of mental and motor skills which impairs communication and socialization.

Infants with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome may have diminished muscle tone (hypotonia) and appear abnormally “floppy.” Hypotonia can affect feeding and impact motor skills such as walking. Feeding difficulties may occur in infancy but tend to resolve once the child ages. They may be described as very quiet and sleep excessively. Some infants may exhibit an abnormally small head circumference (postnatal microcephaly).

Affected infants and children experience delays in reaching developmental milestones, including sitting up or holding one’s head up. They are usually significantly delays in learning to walk. Some children will only be able to walk with assistance while others may be unable to walk. Most children benefit from bracing to stabilize loose ankles. Children who can walk may have an unsteady manner of walking with a wide gait. They may exhibit a lack of coordination (ataxia) and be clumsy. Speech is significantly delayed. Some children develop the ability to speak a few words, but many children are unable to speak. Most children have better receptive language skills, which means that they can understand more information spoken to them than they are able to speak themselves. These children can benefit from assistive communication devices including picture boards and tablet based speaking devices. Many are able to learn and communication to a degree with sign language.

Most affected children have moderate to severe intellectual disability. However, speech and motor abnormalities make it difficult to determine a child’s true mental capacity. Advances in technology and new therapies have enabled affected children to achieve more than originally believed and some physicians and parents believe that there is a broader range of intellectual capability than is generally reported in the medical literature.

Infants and children typically have distinctive facial features. These features include an abnormally wide mouth with a full lower lip; widely-spaced teeth; flared nostrils; a broad bridge of the nose; a sharp, downturned nasal tip; mildly cup-shaped ears; and deep-set eyes that slant slightly upward with a prominent supraorbital ridge. They may have a protruding upper lip that is curved twice (Cupid’s bow), full cheeks and the lower part of the face and chin may be prominent. These distinctive facial features may become more pronounced or noticeable with age.

Children with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome can have irregular or abnormal breathing patterns. They may experience recurrent episodes where they breathe very fast (hyperventilation), often followed by episodes where they struggle to breath or momentarily stop breathing (apnea crises). Apnea can cause cyanosis, a condition in which there is abnormal bluish discoloration to the skin due to lack of oxygen. Breathing irregularities may be triggered by stress, strong emotions, or fatigue. Breathing problems usually do not occur during sleep. The age of onset of breathing abnormalities can vary and has ranged from anywhere from 7 months to 7 years.

Affected children are described as sociable and having a happy disposition, frequently laughing and smiling. Laughter may occur spontaneously or at inappropriate times. However, some children may be quiet or withdrawn into their own world (self-absorption) and have difficulties engaging socially. Episodes of aggression or shouting or agitation, often in response to unexpected changes in routine occur as well. Additional behavioral issues are common and can include hyperactivity, anxiety, self-injury, and shyness. Children with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome also exhibit stereotypic hand movements, which include hand clapping, hand flapping, flicking hands, hand washing, fingers crossing, and frequent hand-to-mouth movements. Head shaking, head banging, body rocking, teeth grinding (bruxism) and hair pulling may also be seen. Children may repeatedly and repetitively play with a toy, and may show a fascination with one specific part of a toy.

Seizures can occur in just under half of individuals and usually begin in childhood, but sometimes are present from birth or develop as late as the teen-age years. Most children experience constipation, which can be severe. Gastroesophageal reflux has been reported in less than half of affected individuals. Most individuals have a high pain threshold.

Additional symptoms can include excessive drooling (especially when younger), severe nearsightedness (myopia), crossed eyes (strabismus), and abnormal curving of the lens of the eye (astigmatism). Abnormal curving of the spine (scoliosis) has occurred in a small number of individuals. Approximately one third of affected males experience failure of one or both testicles to descend into the scrotum (cryptorchidism).

Some minor abnormalities of the hands may be seen including broad fingertips, tapered fingers, curved pinkies (clinodactyly), a single crease across the palm, and prominent pads on the fingertips and toes (persistent fetal pads). There is often an extra crease or absent on the thumb and rare individuals are unable to bend the thumb due to an absent tendon. They often have redness and swelling of the skin at the base of their nails and can have blunting of the normal angle at the baes of the nail (clubbing). They often have overriding toes. Hands and feet may be cold or bluish in appearance due to cyanosis.

Pitt Hopkins syndrome diagnosis

A diagnosis of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome depends upon a detailed patient history, a thorough clinical evaluation, and identification of characteristic symptoms.

Your child’s doctor will do a detailed physical examination which may include the following tests:

- Neurological testing – These tests help to determine how well your child’s muscles, nerves and senses are developing.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) – is a non-invasive method to record electrical activity of the brain along the scalp. EEG measures voltage fluctuations resulting from ionic current flows within the neurons of the brain. EEG is most often used to diagnose epilepsy, which causes abnormalities in EEG readings. An EEG is performed by placing electrodes on the scalp and recording the electrical activity of the brain.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) – This test uses a magnetic field to produce a more detailed picture of the brain than can be done with an EEG or a CT scan. Your child will lie on a table inside the tunnel of the MRI machine. Many children experience claustrophobia when placed inside the scanner, so the acting clinician may give your child a mild sedative before scanning.

- Genetic testing – By studying a small amount of your child’s blood, a geneticist can look for the TCF4 gene mutations that are responsible for Pitt Hopkins Syndrome.

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome should be suspected in individuals with developmental delay, moderate-to-severe intellectual disability, behavioral differences, characteristic facial features, and episodic hyperventilation and/or breath-holding while awake 7.

Developmental delay / intellectual disability / behavioral differences

- Motor milestones are delayed; often with hypotonia.

- Speech is severely limited to absent, with a history of regression in verbal abilities in some.

- Intellectual disability is typically moderate to severe.

- Autism spectrum disorder symptoms are also common, though social engagement is generally present.

- Other behavioral characteristics suggestive of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome include the following:

- Love of music

- Frequent smiling

- Stereotypic hand movements

- Hand flapping

- Spontaneous laughter

Characteristic facial features that become more apparent with age. The craniofacial features are an important aspect for the diagnosis of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, but may be less obvious in infancy. In many individuals, the prominence of the nose and lower face may be the earliest clue to Pitt-Hopkins syndrome in an infant with developmental concerns:

- Deeply set eyes with prominent supraorbital ridges

- Mildly upslanted palpebral fissures

- Broad nasal root, wide nasal ridge, and wide nasal base with enlarged nostrils

- Overhanging or depressed nasal tip, which may be pointed

- Short philtrum

- Thick vermilion of the lower lip, which is often everted

- In some individuals, wide mouth with downturned corners and exaggerated Cupid’s bow or tented vermilion of the upper lip

- Widely spaced teeth

- Prominence of the lower face with a well-developed chin. With age, the lower face becomes more prominent and facial features may coarsen.

- Mildly cupped ears with overfolded helices

Episodic hyperventilation and/or breath-holding while awake. Unusual episodes of hyperventilation (which may be followed by apnea) may occur while awake. When present, this finding (in combination with the developmental history and characteristic facial features) is highly suggestive of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome; however, the absence of a breathing abnormality should not eliminate consideration of the diagnosis of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome as the breathing abnormality may begin sometime in the second half of the first decade, later, or not at all 8.

There is overlap among symptoms associated with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome and other similar neurological disorders. The lack of major congenital malformations, which are structural or functional abnormalities that are present at birth, supports a diagnosis, which can generally be confirmed by molecular testing demonstrating a specific change (mutation) or deletion involving the TCF4 gene. This gene is often included on gene panels that can be ordered for individuals with features of Pitt-Hopkins/Rett/Angelman syndromes. There are individuals with clinical features that can’t be distinguished from Pitt-Hopkins syndrome for which no mutation in TCF4 can be found, and some individuals with variants in TCF4 with a phenotype differing from Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Diagnostic criteria have been published based on published cases, but are being redefined as more molecularly confirmed cases have been identified.

Whalen et al 9 and Marangi et al 10 independently proposed a clinical diagnostic score to aid in the medical decision making regarding which patients should be considered for TCF4 testing (see Table 1 for details of each scoring rubric). On the Whalen et al scale 9, a score of 15 or greater should prompt testing if older than three years of age, 10 or greater if under three years of age. The Marangi et al rubric 10, a score of greater than or equal to 10 out of a possible 16 should prompt testing for Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. In the de Winter et al 11 cohort with molecularly confirmed Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, a score was calculated for 47 participants based on each model and found eight of the items were present in at least 75% of the participants including: severe intellectual disability (47/47, 100%), severe speech impairment (15/15, 100%), walking >3 years/severe motor delay <3 years (44/47, 94%), constipation (40/47, 85%), protrusion mid/lower face (36/47, 77%), broad nasal bridge or convex nasal ridge (44/45, 98%), large mouth (37/47, 79%), and everted vermillion of lower lip (37/36, 80%). Genetic testing for Pitt-Hopkins syndrome would have been indicated in 17% (8/47) and 62% (29/47) based on the Whalen et al score and Marangi et al score, respectively. The scores were diagnostic in 9% (4/47) of the participants based on the Marangi et al score. de Winter et al 11 conclude that a more precise diagnostic criteria and detailed phenotyping are still needed.

Table 1.Clinical diagnostic tools proposed by Whalen et al. and Marangi et al.

| Whalen et al Clinical Diagnostic Score | Marangi et al Clinical Diagnostic Score | ||

| Frequent Features | Positive Points | ||

| Deep set eyes | 1 | Moderate to severe intellectual disability | 2 |

| Protrusion of mid and/or lower face | 1 | Absent speech | 2 |

| Marked nasal root | 1 | Severe speech impairment with more than 10 words vocabulary and/or capacity to form 2–3 word sentences | 1 |

| Broad/beaked nasal bridge | 1 | Normal growth parameters at birth | 1 |

| Flared nostrils | 1 | Postnatal microcephaly or progressive slowing down of head circumference | 1 |

| Large mouth | 1 | Epilepsy/EEG abnormalities | 1 |

| Tented upper lip/prominent Cupid’s bow | 1 | Ataxic gait/Motor incoordination | 1 |

| Everted lower lip | 1 | Breathing Abnormalities: Hyperventilation fits or apnea episodes | 1 |

| Walking >3 years or severe motor delay <3 years | 2 | Mild to severe constipation | 1 |

| Ataxic gait | 1 | Brain MRI abnormalities (corpus callosum hypoplasia, enlargement of the ventricles, and thin hindbrain) | 1 |

| Absent language (or <5 words) | 2 | Ophthalmologic abnormalities (strabismus, myopia, and astigmatism) | 1 |

| Stereotypic movements of the head +/− hands | 2 | Typical Pitt-Hopkins syndrome facial features | 4 |

| Hyperventilation | 1 | Facial features only partially consistent with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome | 2 |

| Hypotonia | 1 | Maximum Score = 16 | |

| Smiling appearance | 1 | >/= 10 should prompt testing for Pitt-Hopkins syndrome | |

| Anxiety/Agitation | 1 | ||

| Strabismus | 1 | ||

| Unusual Features | Negative Points | ||

| Microcephaly </= =3 SD | −2 | ||

| Overgrowth | −1 | ||

| Visceral malformations | −1 | ||

| Loss of purposeful hand skills | −1 | ||

| Maximum Score = 20 | |||

| >15 indication for TCF4 screening | |||

| 10–15 consider TCF4 screening if <3 yr | |||

| <10 no indication for TCF4 screening | |||

Clinical evaluations and workup

If the diagnosis is suspected by exam and history, molecular testing can be ordered. If the diagnosis is confirmed, investigations for other congenital malformations such a heart or kidney defects are only needed if there is a specific clinical concern, as there is not an increased incidence for these with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome.

If seizure activity is seen or suspected – body shaking or staring spells, physicians may recommend an electroencephalogram (EEG), which is a test that measures the electrical activity of the brain and may show changes in brain function and help to detect seizures.

An advanced imaging techniques magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain may also be performed. An MRI uses a magnetic field and radio waves to produce cross-sectional images of particular organs and bodily tissues, including the brain. Physicians use an MRI to obtain a detailed image of a major region of the brain called the cerebrum. A variety of nonspecific brain MRI findings have been seen in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, though many studies are reported as normal.

Pitt Hopkins syndrome treatment

Treatment is directed toward the specific symptoms that are apparent in each individual and generally requires a team of specialists, that can be coordinated by a medical geneticist or your pediatrician. Members of this team may include a pediatric neurologist (a physician who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the brain, nerves and nervous system in children), a gastroenterologist (a physician who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the gastrointestinal tract), an ophthalmologist (a physician who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the eye), a pulmonologist (a physician who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the lungs and breathing issues), a speech pathologist, psychologist, and other healthcare professionals may need to systematically and comprehensively plan an affected child’s treatment. Genetic counseling is of benefit for affected individuals and their families. Psychosocial support for the entire family is essential as well.

Following an initial diagnosis, it is recommended that a developmental assessment be performed and appropriate occupational, physical, speech and feeding therapies be instituted. Periodic reassessments and adjustment of services should be provided with all children. Given the likelihood of severe speech impairment strong consideration should be given to early training with alternative and augmentative communication devices. Children may benefit from treatments used in the treatment of autism spectrum disorder such as applied behavioral analysis (ABA) therapy targeted to the strengths and weaknesses of each child. A developmental pediatrician can help with management of behavioral issues and medication considerations, while more serious aggressive behaviors may be helped by a pediatric psychiatrist. In these individuals who have limited communication, potential medical issues such as severe constipation that might adversely impact behavior should be considered.

Constipation is very common with Pitt-Hopkins and usually standard measures such as high fiber diets or laxatives are sufficient. If there is a significant problem with hyperventilation and/or apnea, advice from a pulmonologist should be sought as in some instances medications such as antiepileptic medications or acetazolamide have been helpful. Seizures that may occur are generally well controlled by anticonvulsants that can be individualized by a neurologist. Most individuals with Pitt-Hopkins will benefit from glasses and some may need surgery for crossed eyes that fail to self-correct. Regular ophthalmology exams are recommended.

Developmental delay and intellectual disability management issues

The following information represents typical management recommendations for individuals with developmental delay / intellectual disability in the United States; standard recommendations may vary from country to country.

- Ages 0-3 years. Referral to an early intervention program is recommended for access to occupational, physical, speech, and feeding therapy. In the US, early intervention is a federally funded program available in all states.

- Ages 3-5 years. In the US, developmental preschool through the local public school district is recommended. Before placement, an evaluation is made to determine needed services and therapies and an Individualized Education Program (IEP) is developed.

- Ages 5-21 years

- In the US, an Individual Education Plan based on the individual’s level of function should be developed by the local public school district. Affected children are permitted to remain in the public school district until age 21.

- Discussion about transition plans including financial, vocation/employment, and medical arrangements should begin at age 12 years. Developmental pediatricians can provide assistance with transition to adulthood.

- All ages. Consultation with a developmental pediatrician is recommended to ensure the involvement of appropriate community, state, and educational agencies and to support parents in maximizing quality of life. Consideration of private supportive therapies based on the affected individual’s needs is recommended. Specific recommendations regarding type of therapy can be made by a developmental pediatrician.

In the US:

- Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA) enrollment is recommended. DDA is a public agency that provides services and support to qualified individuals. Eligibility differs by state but is typically determined by diagnosis and/or associated cognitive/adaptive disabilities.

- Families with limited income and resources may also qualify for supplemental security income for their child with a disability.

Motor dysfunction

Gross motor dysfunction

- Physical therapy is recommended to maximize mobility and to reduce the risk for later-onset orthopedic complications (e.g., contractures, scoliosis, hip dislocation).

- Consider use of durable medical equipment as needed (e.g., wheelchairs, walkers, bath chairs, orthotics, adaptive strollers).

- For muscle tone abnormalities including hypertonia or dystonia, consider involving appropriate specialists to aid in management of baclofen, Botox®, anti-parkinsonian medications, or orthopedic procedures.

Fine motor dysfunction. Occupational therapy is recommended for difficulty with fine motor skills that affect adaptive function such as feeding, grooming, dressing, and writing.

Oral motor dysfunction. Assuming that the individual is safe to eat by mouth, feeding therapy – typically from an occupational or speech therapist – is recommended for affected individuals who have difficulty feeding due to poor oral motor control.

Communication issues.

Strong consideration should be given to early training with alternative means of communication (e.g., Augmentative and Alternative Communication) for those with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, given the presence of severe expressive language difficulties.

Social and behavioral concerns

Children may qualify for and benefit from interventions used in treatment of autism spectrum disorder, including applied behavior analysis (ABA). Applied behavior analysis therapy is targeted to the individual child’s behavioral, social, and adaptive strengths and weaknesses and is typically performed one on one with a board-certified behavior analyst.

Consultation with a developmental pediatrician may be helpful in guiding parents through appropriate behavior management strategies or providing prescription medications when necessary.

Concerns about serious aggressive or destructive behavior can be addressed by a pediatric psychiatrist.

Other Issues

Pulmonary. Some reports indicate that antiepileptic medications control seizures while leaving the unusual respiratory patterns unchanged 12; others have noted some decrease in the frequency of the respiratory episodes with the use of anticonvulsants 13.

- Improvement of an abnormal respiratory pattern after treatment with sodium valproate has been reported in a person with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome with frequent apneic episodes associated with hypoxemia 14.

- Case reports of individuals with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome demonstrated that daily treatment with acetazolamide resulted in decreased frequency and duration of hyperventilatory and apneic episodes and improved oxygen saturation 15.

- Those on acetazolamide should have routine monitoring of electrolytes and acid-base status.

Neurologic. Treatment of epilepsy should be tailored to the type of seizure and individualized to the needs of the affected person. If present, other neurologic issues such as sleep dysfunction should be treated.

Ophthalmologic. Eyeglasses or surgery are indicated as needed for amblyopia. Most, if not all, individuals with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome may exhibit a form of refractive error. These also may appear at any age, and as such there may be a benefit in regular ophthalmologic exams in people with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome.

Gastrointestinal. In most individuals, regular use of high-fiber diet and/or laxative regimen to address constipation and antacids for reflux are appropriate.

Musculoskeletal. Nearly all affected individuals require orthotics for abnormal foot position to aid in ambulation. Orthopedic treatment of scoliosis and other musculoskeletal dysfunction as needed is appropriate.

Other. Standard care is indicated for other medical issues.

Surveillance

Appropriate surveillance includes:

- Ongoing developmental assessments to tailor educational services to an individual’s strengths;

- Regular follow up with an ophthalmologist to monitor for high myopia and strabismus;

- Periodic reevaluation with clinical geneticist and/or genetic counselor to review the most current information and recommendations for individuals with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome.

- Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pitt-hopkins-syndrome

- de Winter CF, Baas M, Bijlsma EK, van Heukelingen J, Routledge S, Hennekam RCM. Phenotype and natural history in 101 individuals with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome through an internet questionnaire system. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2016;11(1):37.

- Zollino, M, Zweier, C, Van Balkom, ID, et al. Diagnosis and management in Pitt‐Hopkins syndrome: First international consensus statement. Clin Genet. 2019; 95: 462– 478. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.13506

- Goodspeed K, Newsom C, Morris MA, Powell C, Evans P, Golla S. Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome: A Review of Current Literature, Clinical Approach, and 23-Patient Case Series. J Child Neurol. 2018;33(3):233–244. doi:10.1177/0883073817750490 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5922265

- Peippo, Maarit & Ignatius, Jaakko. (2012). Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome. Molecular syndromology. 2. 171-180. 10.1159/000335287

- Pitt-Hopkins-like syndrome. https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Disease_Search.php?lng=EN&data_id=18950&Disease_Disease_Search_diseaseGroup=-pitt-hopkins-like-syndrome-&Disease_Disease_Search_diseaseType=Pat&Disease(s)/group%20of%20diseases=Pitt-Hopkins-like-syndrome&title=Pitt-Hopkins-like%20syndrome&search=Disease_Search_Simple

- Sweetser DA, Elsharkawi I, Yonker L, et al. Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome. 2012 Aug 30 [Updated 2018 Apr 12]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK100240

- Marangi G, Ricciardi S, Orteschi D, Lattante S, Murdolo M, Dallapiccola B, Biscione C, Lecce R, Chiurazzi P, Romano C, Greco D, Pettinato R, Sorge G, Pantaleoni C, Alfei E, Toldo I, Magnani C, Bonanni P, Martinez F, Serra G, Battaglia D, Lettori D, Vasco G, Baroncini A, Daolio C, Zollino M. The Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: report of 16 new patients and clinical diagnostic criteria. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1536–45.

- Whalen S, Heron D, Gaillon T, et al. Novel comprehensive diagnostic strategy in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome: clinical score and further delineation of the TCF4 mutational spectrum. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(1):64–72.

- Marangi G, Ricciardi S, Orteschi D, et al. Proposal of a clinical score for the molecular test for Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(7):1604–11.

- de Winter CF, Baas M, Bijlsma EK, van Heukelingen J, Routledge S, Hennekam RC. Phenotype and natural history in 101 individuals with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome through an internet questionnaire system. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11:37.

- Peippo MM, Simola KO, Valanne LK, Larsen AT, Kähkönen M, Auranen MP, Ignatius J. Pitt-Hopkins syndrome in two patients and further definition of the phenotype. Clin Dysmorphol. 2006;15:47–54.

- Takano K, Lyons M, Moyes C, Jones J, Schwartz CE. Two percent of patients suspected of having Angelman syndrome have TCF4 mutations. Clin Genet. 2010;78:282–8.

- Maini I, Cantalupo G, Turco EC, De Paolis F, Magnani C, Parrino L, Terzano MG, Pisani F. Clinical and Polygraphic Improvement of Breathing Abnormalities After Valproate in a Case of Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2012;27:1585–8.

- Gaffney C, McNally P. Successful use of acetazolamide for central apnea in a child with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167:1423.