Pneumaturia

Pneumaturia is the passage of gas or “air” in urine or in the urinary tract. This may be seen or described as “bubbles in the urine” 1. Pneumaturia is the most common presenting symptom of enterovesical fistula, accounting for 50–70% of the cases, followed by fecaluria and recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI) 2. Other causes of pneumaturia include recent urinary tract instrumentation, catheterization or emphysematous cystitis.

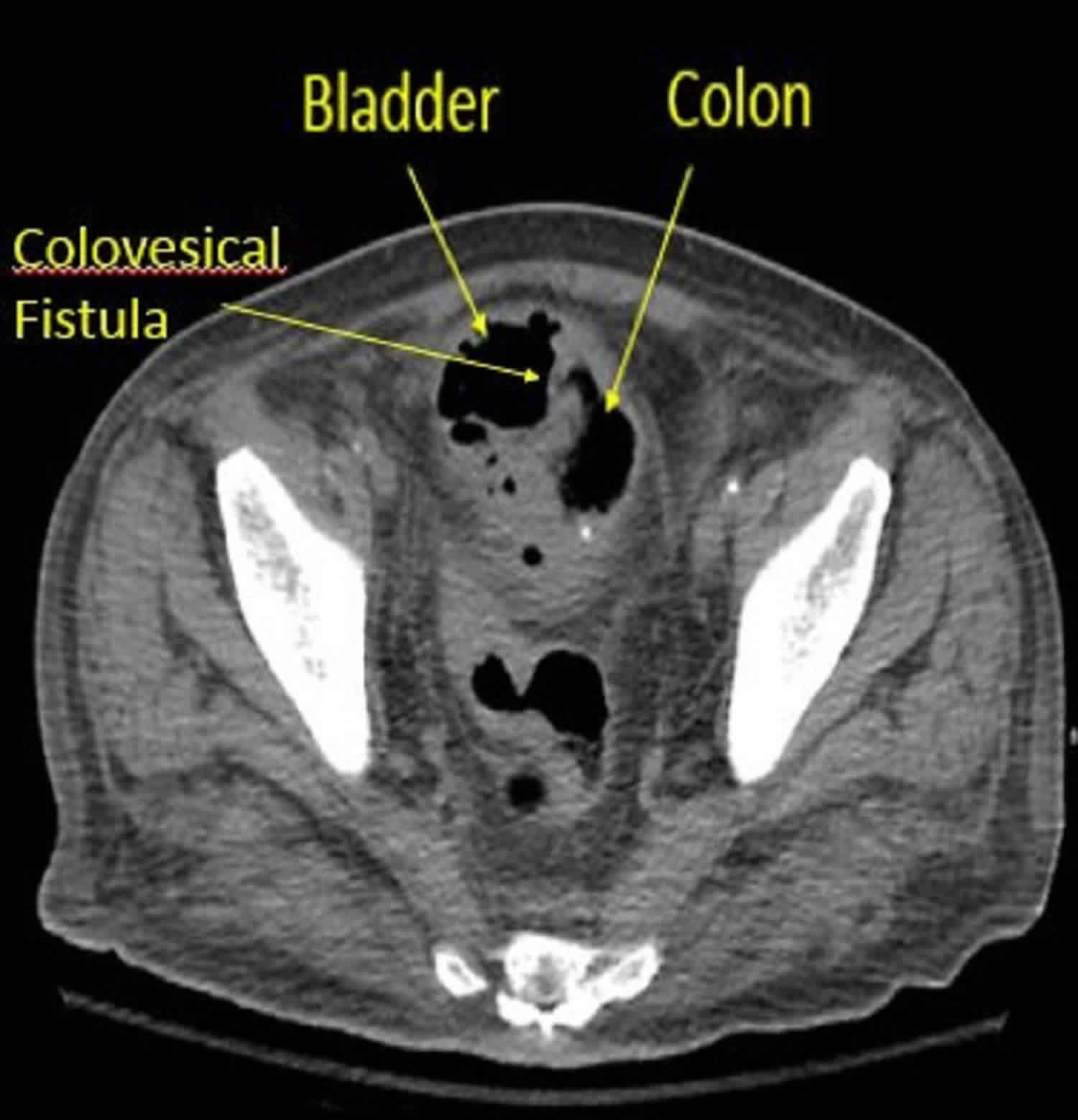

Enterovesical fistula is an abnormal connection between the urinary bladder and the gastrointestinal tract. It can be divided into four types: rectovesical, colovesical, ileovesical and appendicovesical 1. Diverticulitis is the most common cause of colovesical fistula, accounting for 50–70% of the cases, followed by colorectal malignancy. Other causes include Crohn’s disease, infection and iatrogenic trauma. The pathognomonic features of pneumaturia, fecaluria and recurrent urinary tract infections were present in 75% of patients 3.

Pneumaturia key points

- The main cause of pneumaturia is colovesicular fistula secondary complication of diverticulitis

- Pneumaturia is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of colovesicular fistula

- All patients require a CT scan (confirms the diagnosis) of the abdomen and pelvis with oral or rectal contrast and a lower endoscopy (determines cause)

- Treatment is primarily surgical (preferable to use minimally invasive techniques), and most patients are amenable to a single stage surgery sigmoid colectomy and primary anastomosis with repair of bladder

Pneumaturia causes

A common cause of pneumaturia is colovesicular fistula (communication between the colon and bladder). These may occur as a complication of diverticular disease.

Few other processes present with pneumaturia. These include:

- Crohn’s disease

- Carcinoma of the colon or bladder

- Urinary tract infection (UTI) with a gas forming organism (emphysematous cystitis) 4. Emphysematous cystitis is an infection of the bladder wall. Increased risk in people with diabetes and patients with urinary tract outflow obstruction. One will see air within the bladder wall on imaging. Treatment is primarily with antibiotics tailored to urinary cultures.

- Recent urinary tract instrumentation, catheterization.

- Emphysematous pyelonephritis (rarely) 4.

Male scuba divers utilizing condom catheters or female divers using a She-p external catching device for their dry suits are also susceptible to pneumaturia 5.

Colovesicular fistula

A fistula is an irregular connection between two epithelialized surfaces 6. It can be classified or named based on which organs it connects. A connection between the colon and the bladder is termed a “colovesicular fistula.” To understand this disease process and the operative planning, clinicians must understand the intricate anatomy of the pelvis and the organs it contains.

Generally, causes of fistulas can be remembered with the simple mnemonic FRIENDS (Foreign body, Radiation, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Epithelialization, Neoplasm, Distal obstruction, Sepsis [infection]).

The most common cause of colovesicular fistulas is the result of complicated diverticulitis and accounts for over two-thirds of cases 7. The second most common cause is a malignancy in 10% to 20% of cases and is usually adenocarcinoma of the colon. Crohn’s colitis is the third most common cause (5% to 7% of cases) and usually is a result of long-standing disease 7.

Other less common causes of colovesicular fistulas are iatrogenic injury secondary to surgery or procedures, pelvic radiation, abdominal trauma, and tuberculosis (TB).

Diverticular disease, the most common cause for the development of colovesicular fistulas, is a very common disease of western society. Patients older than 60 years of age have a 30% chance of developing diverticulosis and patients older than 80 years of age have an approximately 70% chance. Fifteen percent to 25% of patients with diverticulosis will develop diverticulitis in their lifetime 8, however in a 2013 retrospective review they demonstrated only a 4% lifetime risk 9. The incidence of having a colovesicular fistula in the presence of diverticular disease is 2% to 23% 10.

The average age at presentation for colovesicular fistulas is between 55 and 75 years of age. There is a male predominance secondary to females having a uterus 11, and the majority of females that do develop colovesicular fistulas have had a prior hysterectomy 12.

Pneumaturia symptoms

Pneumaturia is the passage of gas or “air” in urine. This may be seen or described as “bubbles in the urine” 1.

Pneumaturia diagnosis

The goals of the evaluation are to confirm the diagnosis and determine the underlying cause. All patients get a CT scan and lower endoscopic evaluation 13.

CT Scan

The first and best test is a CT scan with oral or rectal contrast without IV contrast (greater than 90% accurate) 7. This will show contrast or air in the bladder with colonic and vesicular wall thickening. It may not show the actual fistula tract but accurately predicts the location. CT scan is also useful for delineating anatomy, discovering tumors, and helps determine underlying etiology.

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy has a low sensitivity (11% to 89%) for detecting fistula tract. It is used to rule out malignancy preoperatively 13.

Cystoscopy

This test also low sensitivity (less than 50%) versus a CT scan for detecting colovesicular fistula. Clinicians usually do not see fistula tract but see edema at the site. It is indicated if there is suspicion for a malignant fistula of the bladder, for example, a history of bladder cancer, bladder mass on CT, or an absence of colonic pathology.

Barium Enema

A barium enema is less commonly done today; CT and endoscopy have largely replaced it. It can be useful in the diagnosis of colovesicular fistula (only 30% Sn) and underlying cause, for example, colon cancer or diverticulosis.

Poppy Seed Test

In this test, the patient ingests poppy seeds, and their urine is examined in 48 hours. It has a 100% detection rate of colovesicular fistula but provides little information regarding disease location or etiology 10.

MRI

MRI is useful in complex fistulas in Crohn’s patients; high-costplain radiography.

Pneumaturia treatment

Pneumaturia treatment involves treating the underlying cause. The cause of the colovesicular fistula must be clear before treatment. This is evaluated with a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis first, followed by a colonoscopy. If there is suspicion for bladder malignancy, then a cystoscopy is warranted.

If there is clinical evidence of infection, treat with systemic antibiotics.

Colovesicular fistula treatment

For surgically unfit patients or patients with inoperable metastatic disease (not a surgical candidate), the following are appropriate:

- Conservative management: Historically believed to not be an option due to high rates of urosepsis and mortality; however, recent analyses of the data have shown that there are minimal morbidity and mortality associated with nonoperative management 14.

- Experimental treatments include endoscopic fibrin glue injection 15 into the fistula tract (used for benign fistula) as well as a covered colonic stent (useful for concomitant malignant fistula and stricture) 16.

Surgically fit patients should have operative repair of colovesicular fistula (open or minimally invasive).

- Most patients should receive a single-stage operation (no increased risk in morbidity or mortality compared to staged operations) 17: Mobilize left colon, separate adherent sigmoid off the bladder, inject methylene blue in Foley to identify the bladder hole, close of bladder hole if big enough to warrant it, resect diseased colon with primary anastomosis, interpose omentum between bladder and colon. If due to malignant disease, require debridement of involved bladder and lymph node harvest

- Patients who are at high risk for an anastomotic leak, for example, a contaminated field with feces or abscess, current steroid use, history of pelvic radiation, hemodynamic instability, should get a staged operation. First stage: Surgery is as above with either primary anastomosis and proximal diverting loop ileostomy or Hartmann’s procedure (end colostomy). The second stage is the reversal of ostomy. In rare instances (not typically done) the Hartmann’s is reversed and also protected with a diverting ileostomy, this will require a third stage operation to reverse the ileostomy.

All patients will require a bladder Foley catheter for a period of 7-10 days postoperatively 18.

A purely diverting ostomy to divert the fecal stream from the colovesicular fistula has fallen out of favor secondary to poor resolution rates, persistent urinary tract infections, and high recurrence rates.

Complications

Complications after elective colon resection for colovesicular fistula 19:

- Mortality: 1% to 2.3%

- Morbidity: 6.4 % to 49% with a median of 19%

- Recurrence: 2.6% to 12.5%

Pneumaturia prognosis

The prognosis of colovesicular fistulas is largely based on the underlying etiology. The most common cause of colovesicular fistula is a benign diverticular disease with a favorable prognosis. Recent publications have shown that there is little to no difference in rates of septicemia, renal failure, and mortality when comparing surgical treatment to the nonsurgical, conservative management of colovesicular fistula 20.

- Complicated diverticular disease (abscess, fistula formation, strictures, and free perforation) is associated with a higher risk of colonic malignancy. There is about a 3% to 5% incidence of concomitant malignancy in patients who have uncomplicated diverticulitis and about an 11% incidence of harboring a malignancy for complicated diverticulitis.

- Patients who have the symptomatic diverticular disease should be evaluated with colonoscopy after acute infection subsides. This is especially true for complicated diverticular cases.

- Clinicians used to be taught that patients who suffer attacks of uncomplicated diverticulitis would subsequently have an increased chance of recurrence and increased chance of complicated disease with each subsequent attack. This has been proven false. Recent analyses of data have shown that patients are more likely to have complicated diverticulitis with their first attack and with each recurrent attack risk of complicated diverticulitis decreases.

- Elective colon resection is indicated for complicated diverticulitis as they have a high recurrence rate of up to 40%. Other indications for elective sigmoidectomy are more controversial.

- ‘Pop goes the whistle’ – Noisy micturition as the main presentation of pneumaturia. Urology Case Reports Volume 23, March 2019, Pages 106-107 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eucr.2019.01.013

- E.S. Rovner. Urinary tract fistulae Wein A.J., et al. (Eds.), Campbell-Walsh Urology (eleventh ed.), Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA (2016), pp. 2223-2226

- T. Golabek, A. Szymanska, T. Szopinski, et al. Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterology research and practice, 2013 (2013), p. 617967, 10.1155/2013/617967

- Tanagho YS, Mobley JM, Benway BM, Desai AC. Gas-producing renal infection presenting as pneumaturia: a case report. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:730549. doi:10.1155/2013/730549 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3654700

- Harris R. Genitourinary infection and barotrauma as complications of ‘P-valve’ use in drysuit divers. Diving Hyperb Med. 2009;39(4):210–212.

- Seeras K, Lopez PP. Colovesicular Fistula. [Updated 2019 Dec 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518990

- Golabek T, Szymanska A, Szopinski T, Bukowczan J, Furmanek M, Powroznik J, Chlosta P. Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:617967

- Scarpignato C, Barbara G, Lanas A, Strate LL. Management of colonic diverticular disease in the third millennium: Highlights from a symposium held during the United European Gastroenterology Week 2017. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756284818771305

- Shahedi K, Fuller G, Bolus R, Cohen E, Vu M, Shah R, Agarwal N, Kaneshiro M, Atia M, Sheen V, Kurzbard N, van Oijen MG, Yen L, Hodgkins P, Erder MH, Spiegel B. Long-term risk of acute diverticulitis among patients with incidental diverticulosis found during colonoscopy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013 Dec;11(12):1609-13.

- Melchior S, Cudovic D, Jones J, Thomas C, Gillitzer R, Thüroff J. Diagnosis and surgical management of colovesical fistulas due to sigmoid diverticulitis. J. Urol. 2009 Sep;182(3):978-82.

- Smeenk RM, Plaisier PW, van der Hoeven JA, Hesp WL. Outcome of surgery for colovesical and colovaginal fistulas of diverticular origin in 40 patients. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2012 Aug;16(8):1559-65.

- Woods RJ, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Weakley FL. Internal fistulas in diverticular disease. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1988 Aug;31(8):591-6.

- Scozzari G, Arezzo A, Morino M. Enterovesical fistulas: diagnosis and management. Tech Coloproctol. 2010 Dec;14(4):293-300.

- Radwan R, Saeed ZM, Phull JS, Williams GL, Carter AC, Stephenson BM. How safe is it to manage diverticular colovesical fistulation non-operatively? Colorectal Dis. 2013 Apr;15(4):448-50.

- Sharma SK, Perry KT, Turk TM. Endoscopic injection of fibrin glue for the treatment of urinary-tract pathology. J. Endourol. 2005 Apr;19(3):419-23.

- Ahmad M, Nice C, Katory M. Covered metallic stents for the palliation of colovesical fistula. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010 Sep;92(6):W43-5.

- Mileski WJ, Joehl RJ, Rege RV, Nahrwold DL. One-stage resection and anastomosis in the management of colovesical fistula. Am. J. Surg. 1987 Jan;153(1):75-9.

- Ferguson GG, Lee EW, Hunt SR, Ridley CH, Brandes SB. Management of the bladder during surgical treatment of enterovesical fistulas from benign bowel disease. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2008 Oct;207(4):569-72.

- Garcea G, Majid I, Sutton CD, Pattenden CJ, Thomas WM. Diagnosis and management of colovesical fistulae; six-year experience of 90 consecutive cases. Colorectal Dis. 2006 May;8(4):347-52.

- Solkar MH, Forshaw MJ, Sankararajah D, Stewart M, Parker MC. Colovesical fistula–is a surgical approach always justified? Colorectal Dis. 2005 Sep;7(5):467-71.