Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

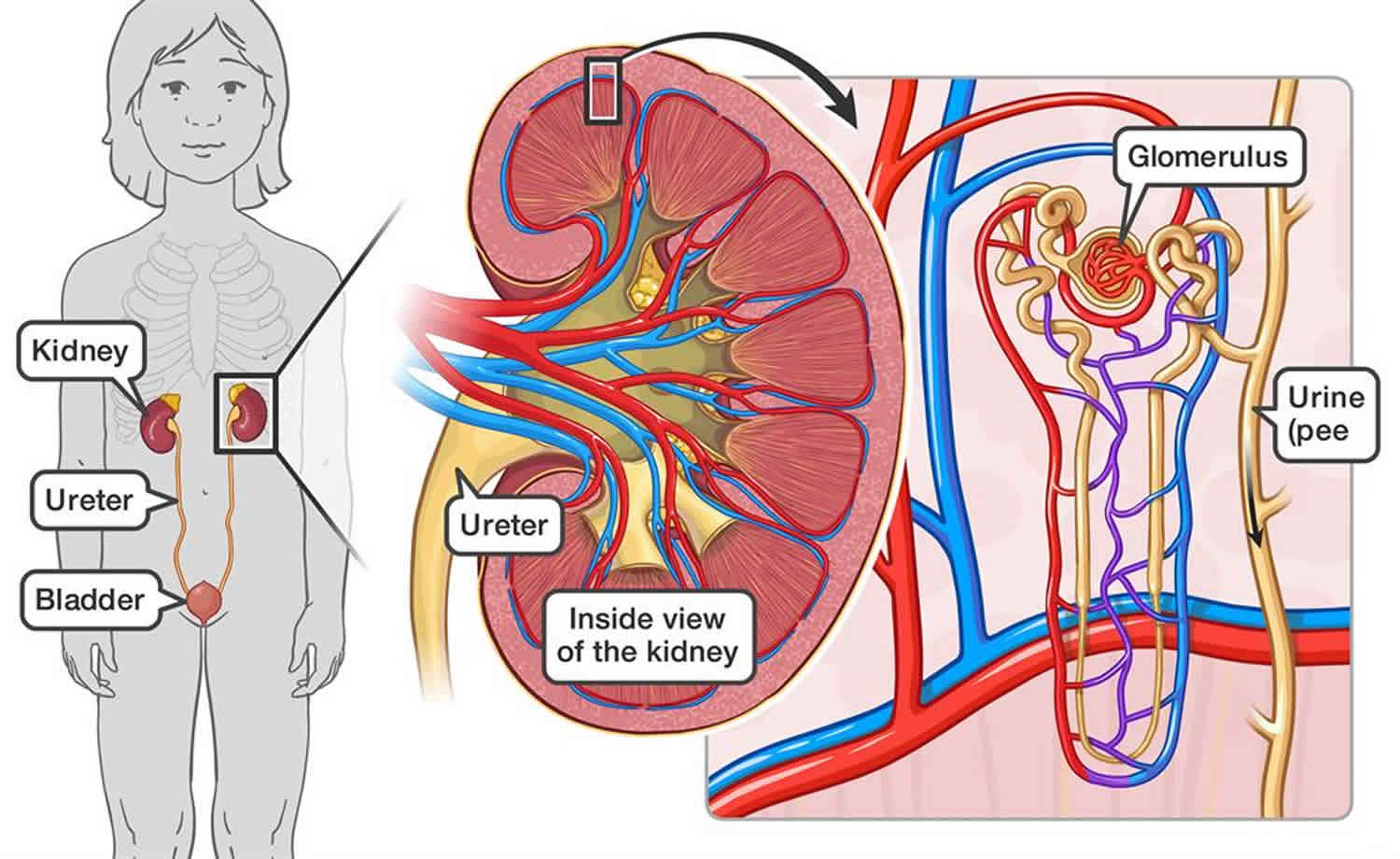

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis also called acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, is a type III hypersensitivity reaction (immune complex-mediated disease) that follows streptococcal infection, which can be a previous skin or throat infection like strep throat, scarlet fever, and impetigo, caused by group A streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes also known as nephrogenic streptococci), or occasionally groups C or G streptococcus 1. The Streptococcus bacterium does not attack the kidneys directly; instead, the group A strep throat or skin infection may stimulate the immune system to overproduce antibodies. Antibodies are proteins made by the immune system. The immune system protects people from infection by identifying and destroying bacteria, viruses, and other potentially harmful foreign substances. When the extra antibodies circulate in the blood and finally deposit in the glomeruli and the small blood vessels of the kidneys, the kidneys can be damaged. Glomerulonephritis is inflammation of the tiny filters in your kidneys (glomeruli). Glomeruli remove excess fluid, electrolytes and waste from your bloodstream and pass them into your urine. Most cases of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis develop 1 to 3 weeks after an untreated group A strep throat or skin infection, though it may be as long as 6 weeks 2. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis lasts only a brief time and the kidneys usually recover. In a few cases, kidney damage may be permanent.

People cannot catch post streptococcal glomerulonephritis from someone else because it is an immune response and not an infection. However, people with a group A strep infection can spread the bacteria to others, primarily through respiratory droplets.

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is more common in children than adults. Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis most frequently presents in children 1 to 2 weeks after a sore throat, or 6 weeks after a skin infection (impetigo) 3. Developing post streptococcal glomerulonephritis after strep throat or scarlet fever is most common in young, school-age children. Developing post streptococcal glomerulonephritis after impetigo is most common in preschool-age children.

When symptomatic, post streptococcal glomerulonephritis typically presents with features of the nephritic syndrome such as swelling (edema), reduced urine output (oliguria), and blood in the urine (hematuria) and high blood pressure (hypertension) 4. Less commonly presentation can mimic nephrotic syndrome with significant proteinuria 4.

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis may occur in epidemic outbreaks or in clusters of cases, and it may occur in isolated patients. Epidemic outbreaks reported in the past as a consequence of upper respiratory or skin streptococcal infections have periodically appeared in specific regions of the world, such as the Red Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota 5; in Port of Spain, Trinidad 6; in Maracaibo, Venezuela 7; and in the Northern Territory of Australia 8. The most recent epidemics have occurred in the indigenous communities of the Northern Territory of Australia, resulting from pyoderma after infection with emm55 group A streptococcus 8 and in the rural region of Nova Serrana, Brazil, caused by the ingestion of unpasteurized milk obtained from cows with mastitis caused by Streptococcus zooepidemicus 9. Streptococcus zooepidemicus has also caused clusters of cases (5–15 patients) reported in the last two decades in poor communities in industrialized countries 10.

In recent decades, the incidence of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis has declined significantly worldwide. The reduction of the incidence of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is probably the result of easier and earlier access to appropriate medical care for streptococcal infections. Reports from France 11, Italy 12, China 13, Chile 14, Singapore 15, the United States 16 and Venezuela 17 all indicate that post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is now an infrequent disease, and its rarity in affluent societies has been considered a factor for delayed diagnosis in patients who do not have gross hematuria 18.

In industrialized countries, post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is now a disease of elderly patients that tend to have debilitating conditions, malignancy, alcoholism, or diabetes 19. Nevertheless, post streptococcal glomerulonephritis remains a significant health problem in underdeveloped societies. Endocapillary glomerulonephritis, assumed to be of poststreptococcal etiology, is the most common glomerulonephritis found in children in developing countries 20 and in aboriginal populations 21. Two independent studies have estimated the incidence of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis in developing countries. Carapetis et al. 22 analyzed 11 population studies and found that the annual burden of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis in developing countries was 9.3 cases per 100,000 people. Rodríguez-Iturbe et al 17 evaluated the incidence of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis in developing countries, using the reports of pediatric acute renal failure due to glomerulonephritis. Rodríguez-Iturbe et al 17 assumed that the cases of acute glomerulonephritis were in fact post streptococcal glomerulonephritis, which was explicitly stated in most series, but not in all. These patients had severe renal failure because they were seen at a referral hospital and admitted to the intensive care unit, if one was available, and then dialyzed. The total number of cases in the general population was estimated, considering that uncomplicated cases of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis are 100 to 300 times more common than those of life-threatening disease. Using this approach, the annual incidence of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis in developing countries was estimated to be 9.5 (low estimate) to 28.5 (high estimate) cases per 100,000 people. This low value is remarkably close to the estimate of Carapetis et al. 22 and the higher value exceeds it by three-fold—yet, these authors acknowledged that theirs was likely an underestimation and that the actual incidence was probably a great deal higher.

One 1960s study found a 10% to 15% attack rate of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis following throat or skin infection with a nephritogenic strain of group A strep 23. An estimated 470,000 cases of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis and 5,000 deaths from post streptococcal glomerulonephritis occur each year globally 24.

Treatment of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis focuses on managing hypertension and edema. Additionally, patients should receive penicillin (preferably penicillin G benzathine) to eradicate the nephritogenic strain. This will prevent spread of the strain to other people 25.

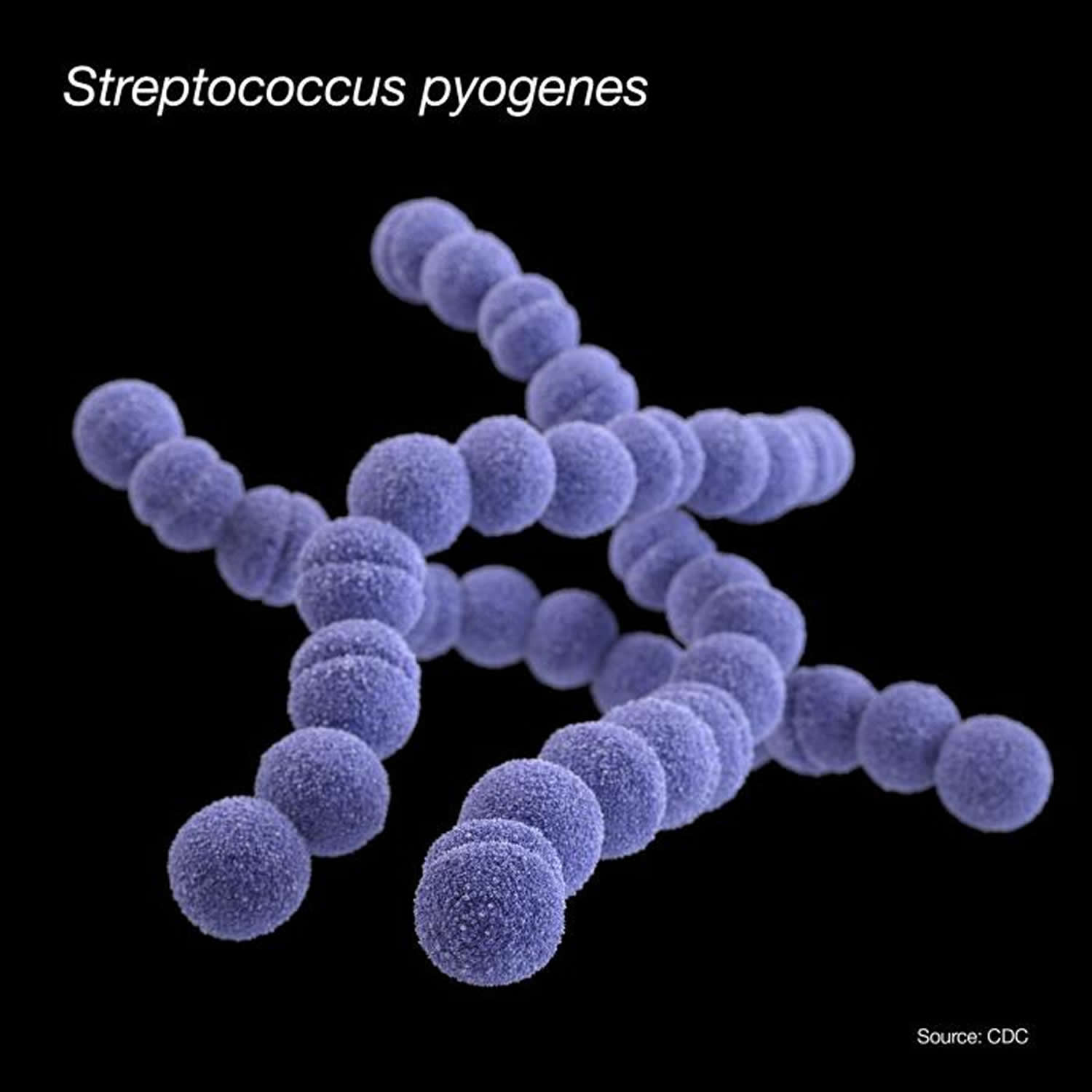

Figure 1. Streptococcus pyogenes

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis causes

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is usually an immunologically-mediated, nonsuppurative, delayed complication of pharyngitis or skin infections caused by nephritogenic strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. Reported outbreaks of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis caused by group C streptococci are rare 26. Streptococcus pyogenes also called group A Streptococcus or group A strep, are Gram-positive cocci that grow in chains (see Figure 1). They exhibit β-hemolysis (complete hemolysis) when grown on blood agar plates. They belong to group A in the Lancefield classification system for β-hemolytic Streptococcus, and thus are called group A streptococci 25.

As a delayed complication of group A strep infection, post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is not contagious. However, people mostly commonly spread group A strep through direct person-to-person transmission. Typically transmission occurs through saliva or nasal secretions from an infected person. Symptomatic people are much more likely to transmit the bacteria than asymptomatic carriers. Crowded conditions — such as those in schools, daycare centers, or military training facilities — facilitate transmission. Although rare, spread of group A strep infections may also occur via food. Foodborne outbreaks of pharyngitis have occurred due to improper food handling. Fomites, such as household items like plates or toys, are very unlikely to spread these bacteria.

Humans are the primary reservoir for group A strep. There is no evidence to indicate that pets can transmit the bacteria to humans.

Risk factors for post streptococcal glomerulonephritis

The risk factors for post streptococcal glomerulonephritis are the same as for the preceding group A strep pharyngitis or skin infection. Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is more common in children, although it can occur in adults. Pharyngitis-associated post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is most common among children of early school age. Pyoderma-associated post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is most common among children of pre-school age.

There are no known risk factors specific for post streptococcal glomerulonephritis. However, the risk of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is increased if a nephritogenic strain of group A strep is introduced into a household.

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis prevention

Unfortunately, antibiotics do not prevent post streptococcal glomerulonephritis from developing in persons with acute streptococcal infections (impetigo or pharyngitis) 26. Thus, it is important to prevent the primary group A streptococcal skin or pharyngeal infection. However, treating post streptococcal glomerulonephritis patients with antibiotics can stop a nephritogenic strain from circulating in a household. Thus treating post streptococcal glomerulonephritis patients can prevent additional infections among close contacts.

Good hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette can reduce the spread of all types of group A strep infection. Hand hygiene is especially important after coughing and sneezing and before preparing foods or eating. Good respiratory etiquette involves covering your cough or sneeze.

To practice good hygiene you should:

- Cover your mouth and nose with a tissue when you cough or sneeze

- Put your used tissue in the waste basket

- Cough or sneeze into your upper sleeve or elbow, not your hands, if you don’t have a tissue

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds

- Use an alcohol-based hand rub if soap and water are not available

You should also wash glasses, utensils, and plates after someone who is sick uses them. These items are safe for others to use once washed.

Antibiotics help prevent spreading the infection to others

Treating an infected person with an antibiotic for 24 hours or longer generally eliminates their ability to transmit the bacteria. Thus, people with group A strep pharyngitis or impetigo should stay home from work, school, or daycare until:

- They no longer have a fever

AND - At least 24 hours after starting appropriate antibiotic therapy

Take the prescription exactly as the doctor says to. Don’t stop taking the medicine, even if you or your child feel better, unless the doctor says to stop.

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis symptoms

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis occurs after a latent period of approximately 10 days following group A strep throat or skin infection. Generally, post streptococcal glomerulonephritis occurs up to 3 weeks following group A strep skin infections 25.

The clinical features of acute glomerulonephritis include:

- Swelling (edema), especially in the face, around the eyes, and in the hands and feet, especially on arising in the morning

- Decreased need to pee or decreased amount of urine

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- Protein in the urine (proteinuria)

- Macroscopic hematuria, with urine appearing dark, reddish-brown

- Complaints of lethargy, generalized weakness, or anorexia

- Feeling tired due to low iron levels in the blood (fatigue due to mild anemia)

Laboratory examination usually reveals:

- Mild normocytic normochromic anemia

- Slight hypoproteinemia

- Elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Low total hemolytic complement and C3 complement

Patients usually have decreased urine output. Urine examination often reveals protein (usually <3 grams per day) and hemoglobin with red blood cell casts.

Additionally, some evidence from epidemic situations indicates that subclinical cases of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis may occur. Thus some individuals may have symptoms that are mild enough to not come to medical attention 25.

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis diagnosis

Clinical history and findings with evidence of a preceding group A strep infection should inform a post streptococcal glomerulonephritis diagnosis. Evidence of preceding group A strep infection can include 25:

- Isolation of group A strep from the throat

- Isolation of group A strep from skin lesions

- Elevated streptococcal antibodies (ASO)

Laboratory investigations are the most useful in post streptococcal glomerulonephritis assessment.

- Evidence of a preceding streptococcal infection is determined by measuring anti-streptolysin titer (ASO), and anti-nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotidase (anti-NAD) which tend to rise following pharyngitis. Other antibodies such as anti-DNAse B and anti-hyaluronidase (AHase) are usually elevated after both pharyngitis and skin infections. ASO (anti-streptolysin) titer is the most frequently used test, while the most sensitive is the streptozyme test; which includes measuring the titers of all the antibodies mentioned above 4.

- Serum complement levels (C3) are usually low due to its consumption in the inflammatory reaction. Mostly, the decrease in C3 concentration occurs before serum ASO has risen 27. Complement levels usually return to normal levels in 6-8 weeks unless the case is complicated.

- Urine analysis: shows macroscopic or microscopic hematuria, red blood cell casts, mild proteinuria. Only 5% of patients with post streptococcal glomerulonephritis have massive proteinuria that indicates nephrotic syndrome. White blood cell casts, hyaline, and cellular casts are usually present in the urine analysis.

Renal function tests

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine typically elevate during the acute phase. These values usually return to normal later.

Histologic studies

Renal biopsy is not recommended for diagnosing patients with post streptococcal glomerulonephritis and is performed only when other glomerular pathologies are suspected.

- Light microscopy: all glomeruli show hypercellularity (endothelial, mesangial, and inflammatory cells). These findings are non-specific and are present in other glomerular pathologies.

- Electron microscopy: the most characteristic finding by electron microscopy is the presence of humps; which are electron-dense deposits in the subepithelial space near the glomerular basement membrane 28.

- Immunofluorescence microscopy: shows deposits of IgG and C3 if the tissue sample was taken in the first 2 to 3 weeks of the disease.

Imaging studies

- Ultrasonography: Kidneys are enlarged only in a few patients.

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis treatment

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis is a self-limiting condition in most cases, and thus only symptomatic treatment is needed.

Treatment of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis focuses on managing symptoms as needed 27:

- Decreasing swelling (edema) by limiting salt and water intake or by prescribing a medication that increases the flow of urine (diuretic) is the initial step to control edema

- Managing high blood pressure (hypertension) through blood pressure medication

- Bed rest and immobilization are recommendations in the first few days of the disease.

People with post streptococcal glomerulonephritis who may still have group A strep in their throat are often provided antibiotics, preferably penicillin.

Pharmacological therapy

- Loop diuretics: 1mg/kg IV furosemide (maximum 40mg) is given to control edema if dietary measures are not sufficient.

- Antihypertensive medications: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), or calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are given to control hypertension if the blood pressure fails to return to normal after diuresis. The first two should be given with caution in patients with impaired kidney functions due to their risk of hyperkalemia.

- Antimicrobials: patients with evidence of a persistent streptococcal infection should receive a course of antibiotic therapy.

- Immunosuppressive therapy: There’s no evidence that immune suppression is useful in patients with post streptococcal glomerulonephritis.[10]

Dialysis

Dialysis is only performed when potassium and creatinine levels are critically high.

Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis prognosis

The prognosis of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis in children is very good; more than 90% of children make a full recovery. Adults with post streptococcal glomerulonephritis are more likely to have a worse outcome due to residual renal function impairment 25 and cardiovascular complication 29. In adults, around 50% of the patients continue to have reduced renal function, hypertension, or persistent proteinuria 30. In elderly patients with debilitating conditions (eg, malnutrition, alcoholism, diabetes, chronic illness), the incidences of azotemia (60%), congestive heart failure (40%), and nephrotic-range proteinuria (20%) are high 31. Death may occur in 20-25% of these patients 32. Prolonged follow-up observation appears to be indicated. The ultimate prognosis in individuals with post streptococcal glomerulonephritis largely depends on the severity of the initial insult.

The long-term prognosis, as related to the development of chronic kidney disease, is also different in children and in adults. In a recent study of a specific outbreak of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis that resulted from the consumption of cheese contaminated with Streptococcus zooepidemicus and that affected mostly adults, there was an alarming incidence of chronic renal disease: impaired renal function was found in 30% of the patients after 2 years of follow-up (10% of them in chronic dialysis therapy) 33. In a particular subgroup of adult patients with post streptococcal glomerulonephritis that had massive proteinuria as the initial manifestation of the disease, the long-term prognosis was especially severe, with an incidence of chronic renal failure as high as 77% 34. The worse prognosis in adults has been attributed to age-related impairment of the Fc-receptor function of the mononuclear phagocyte system 35. Deficiency of the complement factor H-related protein 5 has also been proposed as a factor that may result in a predisposition to the development of chronic renal disease 36.

Regarding the long-term prognosis of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis in children, initial reports in 1930 and 1940 indicated an excellent prognosis, but follow-up periods were relatively short. Subsequent studies have produced widely contrasting results, with the incidence of abnormal laboratory findings ranging from 3.5% 37 to 60% 38. Discrepancies may partially result from the different prognosis of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis in adults and in children, which is not always taken into account in the reported series. Studies by Gallo et al. 39 in the 1980s reported that the incidence of glomerular sclerosis and fibrosis is nearly 50%, but the clinical relevance of these histological characteristics is uncertain. A revision of the follow-up studies in children 10-20 years after the acute episodes found that while approximately 20% of the patients had an abnormal urinalysis or creatinine clearance, less than 1% had developed end-stage kidney disease. 2008 data 17, which includes 110 children with epidemic and sporadic post streptococcal glomerulonephritis followed prospectively over 15–18 years after the acute episode, indicate an incidence of 7.2% of proteinuria, 5.4% of microhematuria, 3.0% of arterial hypertension, and 0.9% of azotemia. These values are essentially similar to those found in the general population. We have also followed 10 cases of subclinical post streptococcal glomerulonephritis for 10–11 years, and the prognosis is excellent. In specific communities, such as in Australian aboriginal groups, it has been found that patients who had post streptococcal glomerulonephritis have an increased risk for albuminuria (adjusted odds ratio of 6.1) and hematuria (odds ratio of 3.7) in relation to controls who did not have post streptococcal glomerulonephritis 40. Finally, the long-term prognosis of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis may be influenced by the coexistence of other risk factors of chronic renal failure. In patients with a history of post streptococcal glomerulonephritis, the association (two-hit) with both diabetes and metabolic syndrome are likely responsible for the high incidence of endstage renal disease in aboriginal communities in Northern Australia 41. It has been reported that persisting arterial stiffness, as determined by brachial–ankle pulse wave velocity, is found in patients with post streptococcal glomerulonephritis who develop chronic renal disease 42.

References- Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Haas M. Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis. 2016 Feb 10. In: Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA, editors. Streptococcus pyogenes : Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations [Internet]. Oklahoma City (OK): University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; 2016-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK333429

- Kidney Disease in Children. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/kidney-disease/children

- Blyth CC, Robertson PW, Rosenberg AR. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis in Sydney: a 16-year retrospective review. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007 Jun;43(6):446-50.

- Rawla P, Ludhwani D. Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis. [Updated 2019 Jun 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538255

- Anthony B. F., Kaplan E. L., Wannamaker L. W., Briese F. W., Chapman S. S. Attack rates of acute nephritis after type 49 streptococcal infection of the skin and of the respiratory tract. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1969;48(9):1697–1704.

- Poon-King T., Mohammed I., Cox R., Potter E. P., Simon N. M., Siegel A. C., et al. Recurrent epidemic nephritis in South Trinidad. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1967;277:728–733.

- Rodríguez-Iturbe B. Epidemic poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Kidney International. 1984;25:129–136.

- Marshall C. S., Cheng A. C., Markey P. G., Towers R. J., Richardson L. J., Fagan P. K., et al. Acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis in the Northern Territory of Australia: a review of 16 years data and comparison with the literature. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2011;85(4):703–710.

- Balter S., Benin A., Pinto S. W., Teixeira L. M., Alvim G. G., Luna E., et al. Epidemic nephritis in Nova Serrana, Brazil. Lancet. 2000;355(9217):1776–1780.

- Nicholson M. L., Ferdinand L., Sampson J. S., Benin A., Balter S., Pinto S. W., et al. Analysis of immunoreactivity to a Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus M-like protein To confirm an outbreak of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, and sequences of M-like proteins from isolates obtained from different host species. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2000;38(11):4126–4130.

- Simon P., Ramée M. P., Autuly V., Laruelle E., Charasse C., Cam G., et al. Epidemiology of primary glomerular diseases in a French region. Variations according to period and age. Kidney International. 1994;46(4):1192–1198.

- Coppo R., Gianoglio B., Porcellini M. G., Maringhini S. Frequency of renal diseases and clinical indications for renal biopsy in children. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 1998;13(2):293–297.

- Zhang Y., Shen Y., Feld L. G., Stapleton F. B. Changing pattern of glomerular disease at Beijing Children’s Hospital. Clinical Pediatrics. 1994;33(9):542–547.

- Berríos X., Lagomarsino E., Solar E., Sandoval G., Guzmán B., Riedel I. Post-streptococcal acute glomerulonephritis in Chile–20 years of experience. Pediatric Nephrology. 2004;19(3):306–312.

- Yap H. K., Chia K. S., Murugasu B., Saw A. H., Tay J. S., Ikshuvanam M., et al. Acute glomerulonephritis–changing patterns in Singapore children. Pediatric Nephrology. 1990;4(5):482–484.

- Roy S., Stapleton F. B. Changing perspectives in children hospitalized with poststreptococcal acute glomerulonephritis. Pediatric Nephrology. 1990;4:585–588.

- Rodríguez-Iturbe B., Musser J. M. The current state of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2008;19(10):1855–1864.

- Pais P. J., Kump T., Greenbaum L. A. Delay in diagnosis in poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;153(4):560–564.

- Montseny J. J., Meyrier A., Kleinknecht D., Callard P. The current spectrum of infectious glomerulonephritis. Experience with 76 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74(2):63–73.

- Rodríguez-Iturbe, B., & Mezzano, S. (2005). Infections and kidney diseases: a continuing global challenge. In M. El Nahas, R. Barsoum, J. H. Dirks, & G. Remuzzi (Eds.), Kidney Diseases in the Developing World and Ethnic Minorities (pp. 59-82). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Currie B. J., Brewster D. R. Childhood infections in the tropical north of Australia. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2001;37(4):326–330.

- Carapetis J. R., Steer A. C., Mulholland E. K., Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2005;5(11):685–694.

- Anthony BF, Kaplan EL, Wannamaker LW, Briese FW, Chapman SS. Attack rates of acute nephritis after Type 49 streptococcal infection of the skin and of the respiratory tract. J Clin Invest. 1969;48(9):1679–704.

- Carapetis JR. The current evidence for the burden of group A streptococcal diseases. World Health Organization. Geneva. 2005.

- Shulman ST, Bisno AL. Nonsupprative poststreptococcal sequelae: Rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis. In Bennett J, Dolin R, Blaser M, editors. 8th ed. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia (PA). Elsevier. 2015;2:2300–9.

- Bryant AE, Stevens DL. Streptococcus pyogenes. In Bennett J, Dolin R, Blaser M, editors. 8th ed. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia (PA). Elsevier. 2015:2:2285–300.

- VanDeVoorde RG. Acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis: the most common acute glomerulonephritis. Pediatr Rev. 2015 Jan;36(1):3-12; quiz 13.

- “Humps” in acute nephritis. Br Med J. 1967 Apr 01;2(5543):4.

- Melby P. C., Musick W. D., Luger A. M., Khanna R. Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis in the elderly. Report of a case and review of the literature. American Journal of Nephrology. 1987;7(3):235–240.

- Kasahara T, Hayakawa H, Okubo S, Okugawa T, Kabuki N, Tomizawa S, Uchiyama M. Prognosis of acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN) is excellent in children, when adequately diagnosed. Pediatr Int. 2001 Aug;43(4):364-7.

- Acute Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/980685-overview

- Lange K, Azadegan AA, Seligson G, Bovie RC, Majeed H. Asymptomatic poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis in relatives of patients with symptomatic glomerulonephritis. Diagnostic value of endostreptosin antibodies. Child Nephrol Urol. 1988-1989. 9(1-2):11-5.

- Pinto S. W., Sesso R., Vasconcelos E., Watanabe Y. J., Pansute A. M. Follow-up of patients with epidemic poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2001;38(2):249–255.

- Vogl W., Renke M., Mayer-Eichberger D., Schmitt H., Bohle A. Long-term prognosis for endocapillary glomerulonephritis of poststreptococcal type in children and adults. Nephron. 1986;44(1):58–65.

- Mezzano S., Lopez M. I., Olavarria F., Ardiles L., Arriagada A., Elqueta S., et al. Age influence on mononuclear phagocyte system Fc-receptor function in poststreptococcal nephritis. Nephron. 1991;57(1):16–22.

- Vernon K. A., Goicoechea de Jorge E., Hall A. E., Fremeaux-Bacchi V., Aitman T. J., Cook H. T., et al. Acute presentation and persistent glomerulonephritis following streptococcal infection in a patient with heterozygous complement factor H-related protein 5 deficiency. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2012;60(1):121–125.

- Potter E. V., Lipschultz S. A., Abidh S., Poon-King T., Earle D. P. Twelve to seventeen-year follow-up of patients with poststreptococcal acute glomerulonephritis in Trinidad. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1982;307(12):725–729.

- Baldwin D. S., Gluck M. C., Schacht R. G., Gallo G. The long-term course of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1974;80(3):342–358.

- Gallo G. R., Feiner H. D., Steele J. M., Schacht R. G., Gluck M. C., Baldwin D. S. Role of intrarenal vascular sclerosis in progression of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Clinical Nephrology. 1980;13(2):49–57.

- Hoy W. E., Mathews J. D., McCredie D. A., Pugsley D. J., Hayhurst B. G., Rees M., et al. The multidimensional nature of renal disease: rates and associations of albuminuria in an Australian Aboriginal community. Kidney International. 1998;54(4):1296–1304.

- Hoy W. E., White A. V., Dowling A., Sharma S. K., Bloomfield H., Tipiloura B. T., et al. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis is a strong risk factor for chronic kidney disease in later life. Kidney International. 2012;81(10):1026–1032.

- Yu M. C., Yu M. S., Yu M. K., Lee F., Huang W. H. Acute reversible changes of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in children with acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Pediatric Nephrology. 2011;26(2):233–239.