Proctocolitis

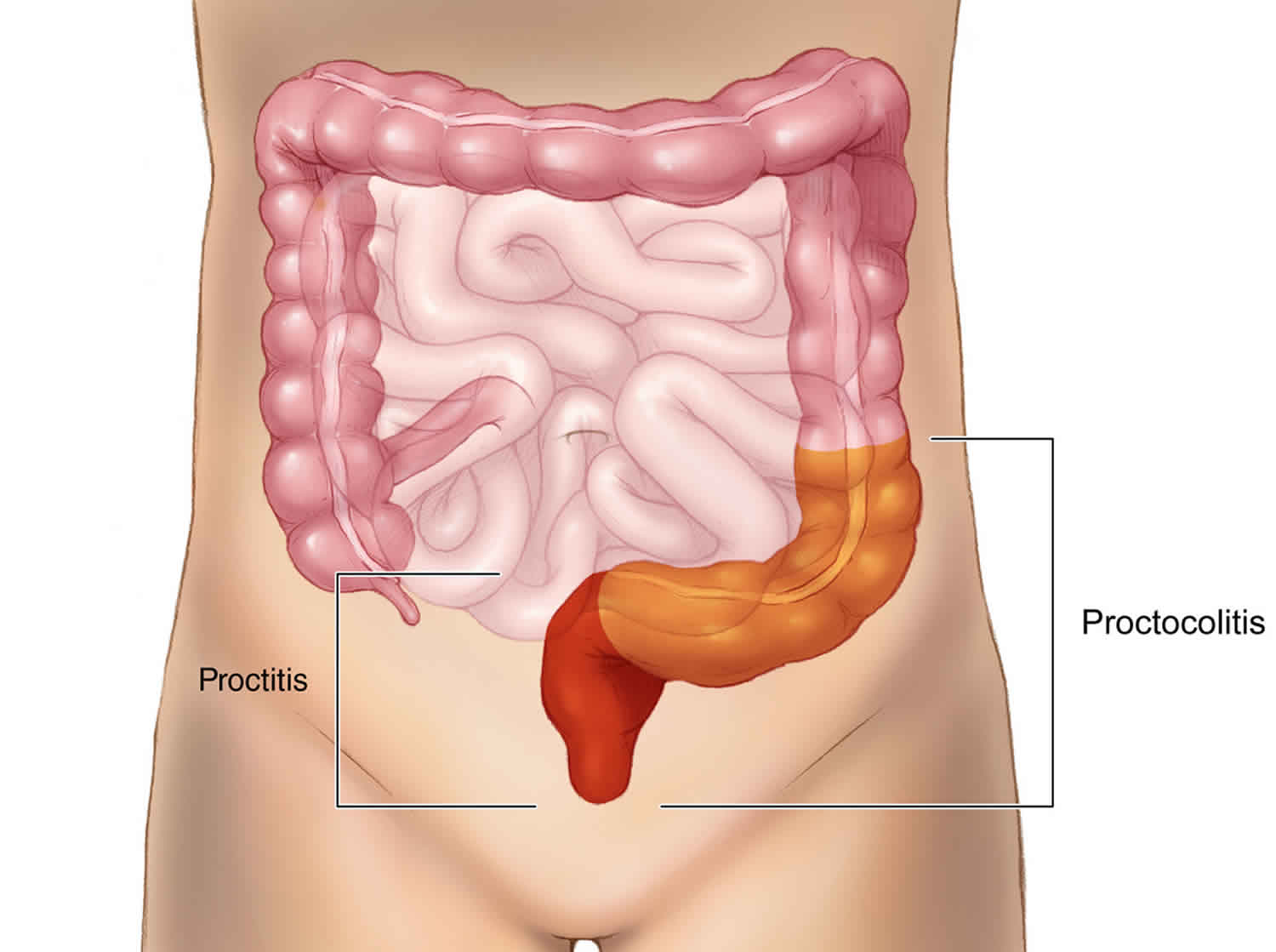

Proctocolitis is a medical term for the inflammation of the rectum (proctitis) and the inflammation of the colon (colitis) usually the distal part of the colon 12 cm to 15 cm above the anus (sigmoid colon).

Proctitis can be associated with anorectal pain, tenesmus, or rectal discharge. Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhoea), Chlamydia trachomatis including lymphogranuloma venereum serovars, Treponema pallidum (syphilis) and herpes simplex virus (genital herpes) are the most common sexually transmitted pathogens involved. Lymphogranuloma venereum is a sexually transmitted infectious disease caused by the L1, L2, and L3 serovars of the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis. Since 2003, outbreaks of lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis have emerged in Western Europe and North America and disproportionately affect men who have sex with men 1. In persons with HIV infection, herpes proctitis can be especially severe. Proctitis occurs predominantly among persons who participate in receptive anal intercourse.

Proctocolitis is associated with symptoms of proctitis, diarrhea or abdominal cramps, and inflammation of the colonic mucosa extending to 12 cm above the anus. Fecal leukocytes might be detected on stool examination, depending on the pathogen. Pathogenic organisms include Campylobacter sp., Shigella sp., Entamoeba histolytica, and lymphogranuloma venereum serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis. Cytomegalovirus or other opportunistic agents can be involved in immunosuppressed HIV-infected patients. Proctocolitis can be acquired through receptive anal intercourse or by oral-anal contact, depending on the pathogen.

The risk of developing lymphogranuloma venereum is related to lifestyle and sexual practices. Acute infection requires direct inoculation of the Chlamydia bacteria in to host tissue. In the case of lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis, infection transmission is often via anal receptive intercourse 2. As with other sexually transmitted infections, promiscuity, and intercourse with multiple partners place a patient at increased risk for contracting the disease. As lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis has disproportionately affected homosexual men, studies have attempted to identify risk factors or behavioral patterns within this population that place an individual at increased risk for developing lymphogranuloma venereum. Using questionnaires to identify differences between asymptomatic and symptomatic homosexual men, those with lymphogranuloma venereum were more likely to have had unprotected receptive or insertive anal intercourse including fisting, have had multiple partners or “one-off” sexual encounters, had concurrent recreational drug and alcohol use (GHB and methamphetamines most commonly reported), and shared sex toys 3.

Before 2003, lymphogranuloma venereum was uncommon in the Western world. lymphogranuloma venereum was primarily endemic to tropical climates such as East and West Africa, India, Southeast Asia and the Caribbean with low prevalence in the industrialized world 4. As such, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) input, voted to cease mandated reporting of the disease in 1995 5. In 2003, an outbreak of lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis amongst HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Rotterdam, the Netherlands occurred which prompted a concerted effort to warn the international medical community. Shortly after the initial outbreak, published case reports demonstrated the presence of lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis in multiple large European cities. Countries in Western Europe and North America began to implement surveillance protocols amongst high-risk patients. Despite these efforts, a decade later, lymphogranuloma venereum was not mandated as a reportable infection in several European countries. Even today, only twenty-four states in the US mandate the reporting of lymphogranuloma venereum cases to the CDC, limiting data to determine disease prevalence. At the time it is still not universally mandated to report cases of lymphogranuloma venereum. Thus true epidemiologic figures remain elusive. Moreover, as noted in the 2016 European CDC’s annual epidemiological report, present surveillance strategies focus primarily on high-risk populations (men who have sex with men, patients with HIV/AIDS or other sexually transmitted infections [STIs]), it difficult to generate data applicable to the general population.

Though the determination of lymphogranuloma venereum incidence and prevalence has been challenging, data reflects a disease on the rise that disproportionately affects men who have sex with men. In 2004, as a result of the European outbreak, enhanced surveillance strategies were put in place in multiple European countries (Netherlands, UK, Germany, France, Sweden). The European Surveillance of Sexually Transmitted Infections (ESSTI) network was formed and enabled the sharing of data, along with the creation of alerts through the ESSTI_ALERT system. Using this data identified 1693 cases of lymphogranuloma venereum across eight European countries from 2004 to 2008. In all reporting countries, the incidence was trending upward. This data included countries without any lymphogranuloma venereum cases in the early stages of the outbreak, such as Denmark, Portugal, and Spain 6. The number of cases reported was particularly significant, considering the incidence in the Netherlands had been roughly five cases annually before 2003 7. Ongoing collection of data published by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) has continued to show a rise in the incidence of lymphogranuloma venereum. In 2014, ECDC data compiled from 21 reporting European countries revealed 1416 reported cases that year alone, a 32% increase from 2013. The vast majority of cases reported in the ECDC data (87%) were noted to be from France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, and almost all cases reported were among men who have sex with men. A population-based incidence study performed in Barcelona from January 2007 to December 2011 discovered an increase in incidence amongst men who have sex with men of 1,032% during the study period 8. In the United States, specific data regarding lymphogranuloma venereum has not been available from the CDC. It is worth noting that reported cases of Chlamydia infection in the US have continued to rise annually per the CDC’s surveillance data.

Patients with HIV have been disproportionately affected by lymphogranuloma venereum infections. In the ECDC data, of patients with a known HIV status, 87% of confirmed lymphogranuloma venereum cases occurred in HIV-positive patients. In a meta-analysis performed by Dougan et al. 9, it was concluded that from 1996 to 2006, HIV-positive men who have sex with men accounted for 75% of lymphogranuloma venereum cases on average in Western Europe alone. A prospective, multicenter study in Germany recruited a sample of men who have sex with men to evaluate the prevalence of multiple STIs in Germany over one year from December 2009 to December 2010. Their data revealed that 58% of lymphogranuloma venereum positive patients were also HIV-positive 7. In a meta-analysis by Ronn and Ward, the authors noted that thirteen descriptive studies had shown at least two-thirds of men who have sex with men with lymphogranuloma venereum were co-infected with HIV. In the same analysis, pooled data from 17 studies from 2000-2009 showed HIV-positive men who have sex with men were greater than eight times as likely to have HIV than those who had non-lymphogranuloma venereum Chlamydia infections. This data demonstrated an association that was stronger than other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) that had reemerged during the same timeframe 10. Proposals are that improved survival in the post-HAART era and serosorting (the practice of using HIV status as a decision making strategy when participating in sexual activity) were likely factors contributing to this association 9.

Other prevalence estimates and case-control studies have shown that HIV-infected men who have sex with men are disproportionately affected by the emergence of lymphogranuloma venereum due to an underlying pathophysiologic mechanism. Brenchley et al. 11 proposed that acute and chronic infection with HIV cause impairment or depletion of effector-type T cells in gastrointestinal mucosa resulting in rapid depletion of CD4+ T cells. By decreasing and inhibiting mucosal immune integrity, HIV may facilitate other co-infection such as syphilis and chlamydia 12. Moreover, the direct inoculation of infection into the rectal mucosa during receptive intercourse facilitates transmission in an already susceptible population. The susceptibility of HIV infected individuals in acquiring lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis is likely a combination of risky sexual behavior and T-cell immunodeficiency 12.

Proctocolitis infant

Food Protein-Induced Allergic Proctocolitis

Food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP) is a type of delayed inflammatory non-IgE mediated gut food allergy. Symptoms usually start at one to four weeks of age and range from having blood, which is sometimes seen with mucous in bowel movements, to blood stained loose stools or diarrhoea. Infants with food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis are usually otherwise healthy and growing well. Food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP) mostly occurs in breastfed infants, but can also occur once cow’s milk or soy based formula is commenced. The main triggers are cow’s milk or soy.

Diagnosis of food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis

Allergy tests (skin tests or blood tests for Immunoglobulin E [IgE] antibodies) are negative for infants with food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis and therefore not useful.

Diagnosis is based on:

- Excluding diagnosis of other causes of blood in bowel movements or blood stained diarrhoea, such as gastroenteritis, infections, anal fissures, or bowel malformations/anomaly.

- If food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis is considered likely, then symptoms should resolve once the offending food/s are eliminated from the breastfeeding mother’s and/or infant’s diet.

- After symptoms have resolved, the offending food/s may be re-introduced to confirm the diagnosis.

Management of food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis

If breastfeeding:

- Cow’s milk (and all dairy) should be removed from the breastfeeding mother’s diet (a dietician may be required to assist). Most cases resolve with elimination of cow’s milk within 48–72 hours, but sometimes longer.

- If symptoms do not resolve, further changes to the breastfeeding mother’s diet should only be made after seeking medical advice.

- Once symptoms have resolved, the eliminated foods may be re-introduced into the breastfeeding mother’s diet to confirm the offending food/s.

- If more than one food protein is restricted from the breastfeeding mother’s diet, this will need supervision by a dietitian, to ensure nutritional adequacy and to prevent excess weight loss in the mother. Maternal calcium requirements during breastfeeding are 1,000mg/day which can be supplied with 800mL/day of calcium fortified cow’s milk replacement such as soy (unless you have been asked to avoid this), rice, almond or oat milk. A calcium supplement may be recommended as this quantity of milk replacement is difficult to consume on a daily basis. If it is a nut, grain or coconut milk substitute then an additional serve of protein should be eaten daily and also a multivitamin taken containing Vitamin B2 (riboflavin).

If an infant is formula fed:

- It is important to seek medical advice before restricting an infant’s diet, to ensure they receive optimal nutrition. Improvement is usually seen within three to seven days, but it can take up to two weeks.

- If no improvement is seen, your doctor may recommend an extensively hydrolyzed formula or occasionally an amino acid formula. You will need a specialist referral, especially if amino acid formula is recommended.

Resolution of food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis

- Resolution of food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis usually occurs in 50% of infants by the age of six months, and 95% of infants by the age of nine months.

- It is generally recommended to reintroduce the offending food/s to the mother’s or infant’s diet after it has been eliminated for six months or at 12 months of age.

- For infants who have more severe symptoms, such as blood stained diarrhoea, the offending food/s may be gradually introduced under the supervision of a dietitian.

Food Protein Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome

Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) is an adverse food reaction involving the immune system that mainly affects infants and young children. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) is caused by an allergic reaction to one or more ingested foods which results in inflammation of the small and large intestine.

Symptoms of profuse vomiting (and sometimes diarrhoea) most commonly occur two to four hours after eating a food that has been recently introduced into the diet. Some children may become pale, floppy, have reduced body temperature, and/or blood pressure during a reaction.

Avoidance of the trigger food protein/s is currently the only effective treatment option. However, most children will outgrow their food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome in the preschool years.

How is food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome different to many common food allergies?

It is possible for a child with food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome to also have Immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated allergies to other foods and to have other allergic diseases such as eczema and asthma. However, food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome is not caused by IgE, and:

- Is usually a delayed reaction.

- Reactions only involve the gastrointestinal system.

- No hives, welts or swellings are seen on the face or body.

- Is not associated with anaphylaxis.

- Adrenaline (epinephrine) autoinjectors are NOT used to treat the reaction.

Which foods can trigger food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome?

The most common food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome triggers are rice, cow’s milk (dairy) and soy. However, almost any food can cause an food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome reaction, including cereals such as rice, oats, eggs, legumes and meats such as chicken and seafood. food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome rarely occurs in exclusively breastfed infants.

Is it possible to have food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome to more than one food?

Some children have food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome to more than one food protein. For example, some children with food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome to cow’s milk have been noted to react to soy, and some with food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome to rice have also reacted to oats. Children with food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome to chicken may react to other poultry such as turkey.

Does food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome resolve?

Most children outgrow food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome by about three to four years of age. However, this varies between individuals and foods. Only 40-80% of children with food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome to rice, and 60% to dairy, tolerated these foods by the ages of three to four. The best way to determine whether a child has outgrown their food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome is by a medically supervised food challenge.

Symptoms of food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome

A typical food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome reaction begins with profuse vomiting around 2 to 4 hours after ingesting the trigger food/s, often followed by diarrhoea which can last for several days. Occasionally a shorter time frame may be seen. In the most severe food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome reactions, vomiting and diarrhoea can cause serious dehydration. Children with food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome can have poor growth if they continue to ingest trigger food/s.

Food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome diagnosis

There are no laboratory or skin tests which can confirm a diagnosis of food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome. This makes diagnosis difficult.

- During an food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome reaction some children may have an elevated white cell and platelet count, and may be mistaken for having an infection.

- Skin tests or blood tests for allergen specific IgE to the food protein/s are not helpful.

- Medically supervised oral food challenges can be useful when the history is not clear, or when other foods from similar food groups are being introduced into the diet for the first time.

- Medically supervised oral food challenges can be useful to establish when a child has outgrown food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome.

Food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome treatment

Currently the only specific management option for food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome is avoidance of the trigger food/s.

Infants who have reacted to cow’s milk and soy formulas will usually be trialed on extensively hydrolyzed formula or amino acid based formula, if extensively hydrolyzed formula is not tolerated.

Most families of children with food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome will be given a letter to present to emergency departments explaining their child’s condition and the appropriate treatment.

Treatment during an food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome reaction may include:

- Intravenous (IV) fluids, because of the risk of dehydration.

- Corticosteroids and in-hospital monitoring, for more severe symptoms.

There is no role for the use of adrenaline (epinephrine) autoinjectors in the management of food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome .

Proctocolitis causes

Proctocolitis has many possible causes. Common infectious causes of proctocolitis include Chlamydia trachomatis, lymphogranuloma venereum, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, herpes simplex virus (HSV), Shigella dysenteriae and Campylobacter species. It can also be allergic (e.g. food protein-induced proctocolitis), idiopathic (e.g. microscopic colitis), vascular (e.g. ischemic colitis), or autoimmune (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease) (see Table 1).

Proctitis has many possible causes. It may occur idiopathically (idiopathic proctitis, that is, arising spontaneously or from an unknown cause). Other causes include damage by irradiation (for example in radiation therapy for cervical cancer and prostate cancer) or as a sexually transmitted infection, as in lymphogranuloma venereum and herpes proctitis. Studies suggest a celiac disease-associated “proctitis” can result from an intolerance to gluten 13. A common cause is engaging in anal sex with partner(s) infected with sexual transmitted diseases in men who have sex with men 14. Shared enema usage has been shown to facilitate the spread of Lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis 15.

Table 1. Colitis classification by cause

| Classes of Colitis | Disorders |

| Autoimmune |

|

| Allergic |

|

| Infectious colitis |

|

| Idiopathic |

|

| Iatrogenic |

|

| Vascular |

|

| Drug induced |

|

| Unclassifiable |

|

Colitis classification by age

- Infantile (first six months of life) 16

- Adult

Colitis classification by duration of symptoms

Proctocolitis symptoms

The signs and symptoms of proctocolitis are quite variable and dependent on the cause of the given proctitis and colitis and factors that modify its course and severity.

The main symptoms of ulcerative colitis are:

- recurring diarrhea, which may contain blood, mucus or pus

- tummy pain

- needing to empty your bowels frequently

You may also experience extreme tiredness (fatigue), loss of appetite and weight loss.

The severity of the symptoms varies, depending on how much of the rectum and colon is inflamed and how severe the inflammation is.

For some people, the condition has a significant impact on their everyday lives.

Symptoms of ulcerative colitis flare-up:

Some people may go for weeks or months with very mild symptoms, or none at all (remission), followed by periods where the symptoms are particularly troublesome (flare-ups or relapses).

During a flare-up, some people with ulcerative colitis also experience symptoms elsewhere in their body.

For example, some people develop:

- painful and swollen joints (arthritis)

- mouth ulcers

- areas of painful, red and swollen skin

- irritated and red eyes

In severe cases, defined as having to empty your bowels 6 or more times a day, additional symptoms may include:

- shortness of breath

- a fast or irregular heartbeat

- a high temperature (fever)

- blood in your stools becoming more obvious

In most people, no specific trigger for flare-ups is identified, although a gut infection can occasionally be the cause.

Stress is also thought to be a potential factor.

Proctitis is an inflammation of the anus and the lining of the rectum, affecting only the last 6 inches of the rectum. A common symptom of proctitis is a continual urge to have a bowel movement—the rectum could feel full or have constipation. Another is tenderness and mild irritation in the rectum and anal region. A serious symptom is pus and blood in the discharge, accompanied by cramps and pain during the bowel movement. If there is severe bleeding, anemia can result, showing symptoms such as pale skin, irritability, weakness, dizziness, brittle nails, and shortness of breath.

Symptoms are ineffectual straining to empty the bowels, diarrhea, rectal bleeding and possible discharge, a feeling of not having adequately emptied the bowels, involuntary spasms and cramping during bowel movements, left-sided abdominal pain, passage of mucus through the rectum, and anorectal pain.

Sexually transmitted proctitis

Gonorrhea (Gonococcal proctitis)

This is the most common cause. Strongly associated with anal intercourse. Symptoms include soreness, itching, bloody or pus-like discharge, or diarrhea. Other rectal problems that may be present are anal warts, anal tears, fistulas, and hemorrhoids.

Chlamydia (chlamydia proctitis)

Accounts for twenty percent of cases. People may show no symptoms, mild symptoms, or severe symptoms. Mild symptoms include rectal pain with bowel movements, rectal discharge, and cramping. With severe cases, people may have discharge containing blood or pus, severe rectal pain, and diarrhea. Some people have rectal strictures, a narrowing of the rectal passageway. The narrowing of the passageway may cause constipation, straining, and thin stools.

Herpes Simplex Virus 1 and 2 (herpes proctitis)

Symptoms may include multiple vesicles that rupture to form ulcers, tenesmus, rectal pain, discharge, hematochezia. The disease may run its natural course of exacerbations and remissions but is usually more prolonged and severe in patients with immunodeficiency disorders. Presentations may resemble dermatitis or decubitus ulcers in debilitated, bedridden patients. A secondary bacterial infection may be present.

Syphilis (syphilitic proctitis)

The symptoms are similar to other causes of infectious proctitis; rectal pain, discharge, and spasms during bowel movements, but some people may have no symptoms. Syphilis occurs in three stages.

- The primary stage: One painless sore, less than an inch across, with raised borders found at the site of sexual contact, and during acute stages of infection, the lymph nodes in the groin become diseased, firm, and rubbery.

- The secondary stage: A contagious diffuse rash that may appear over the entire body, particularly on the hands and feet.

- The third stage: Occurs late in the course of syphilis and affects mostly the heart and nervous system.

Proctocolitis diagnosis

Doctors can diagnose proctocolitis by looking inside the rectum with a proctoscope or a sigmoidoscope. A biopsy is taken, in which the doctor scrapes a tiny piece of tissue from the rectum, and this tissue is then examined by microscopy. The physician may also take a stool sample to test for infections or bacteria. If the physician suspects that the patient has Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, colonoscopy or barium enema X-rays are used to examine areas of the intestine.

Persons who present with symptoms of acute proctitis should be examined by anoscopy. A Gram-stained smear of any anorectal exudate from anoscopic or anal examination should be examined for polymorphonuclear leukocytes. All persons should be evaluated for herpes simplex virus (by PCR or culture), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NAAT or culture), Chlamydia trachomatis (NAAT), and Treponema pallidum (Darkfield if available and serologic testing). If the Chlamydia trachomatis test is positive on a rectal swab, a molecular test PCR for lymphogranuloma venereum should be performed, if available, to confirm an lymphogranuloma venereum diagnosis.

Proctocolitis treatment

Acute proctitis of recent onset among persons who have recently practiced receptive anal intercourse is usually sexually acquired 18. Presumptive therapy should be initiated while awaiting results of laboratory tests for persons with anorectal exudate detected on examination or polymorphonuclear leukocytes detected on a Gram-stained smear of anorectal exudate or secretions; such therapy also should be initiated when anoscopy or Gram stain is unavailable and the clinical presentation is consistent with acute proctitis in persons reporting receptive anal intercourse.

Recommended antibiotic regimen 19:

- Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM in a single dose PLUS

- Doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 7 days

Bloody discharge, perianal ulcers, or mucosal ulcers among men who have sex with men with acute proctitis and either a positive rectal chlamydia NAAT or HIV infection should be offered presumptive treatment for lymphogranuloma venereum with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily orally for a total of 3 weeks 20. If painful perianal ulcers are present or mucosal ulcers are detected on anoscopy, presumptive therapy should also include a regimen for genital herpes (see management of genital herpes below).

To minimize transmission and reinfection, men treated for acute proctitis should be instructed to abstain from sexual intercourse until they and their partner(s) have been adequately treated (i.e., until completion of a 7-day regimen and symptoms resolved). All persons with acute proctitis should be tested for HIV and syphilis.

Follow-Up

Follow-up should be based on specific etiology and severity of clinical symptoms. For proctitis associated with gonorrhea or chlamydia, retesting for the respective pathogen should be performed 3 months after treatment.

Management of Sex Partners

Partners who have had sexual contact with persons treated for gonorrhea, chlamydia or lymphogranuloma venereum within the 60 days before the onset of the persons symptoms should be evaluated, tested, and presumptively treated for the respective pathogen. Partners of persons with sexually transmitted enteric infections should be evaluated for any diseases diagnosed in the person with acute proctitis. Sex partners should abstain from sexual intercourse until they and their partner with acute proctitis are adequately treated.

Management of genital herpes

Antiviral chemotherapy offers clinical benefits to most symptomatic patients and is the mainstay of management. Counseling regarding the natural history of genital herpes, sexual and perinatal transmission, and methods to reduce transmission is integral to clinical management.

Systemic antiviral drugs can partially control the signs and symptoms of genital herpes when used to treat first clinical and recurrent episodes or when used as daily suppressive therapy. However, these drugs neither eradicate latent virus nor affect the risk, frequency, or severity of recurrences after the drug is discontinued. Randomized trials have indicated that three antiviral medications provide clinical benefit for genital herpes: acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir 21. Valacyclovir is the valine ester of acyclovir and has enhanced absorption after oral administration. Famciclovir also has high oral bioavailability. Topical therapy with antiviral drugs offers minimal clinical benefit and is discouraged.

First clinical episode of genital herpes

Newly acquired genital herpes can cause a prolonged clinical illness with severe genital ulcerations and neurologic involvement. Even persons with first-episode herpes who have mild clinical manifestations initially can develop severe or prolonged symptoms. Therefore, all patients with first episodes of genital herpes should receive antiviral therapy.

Recommended regimens 22:

- Acyclovir 400 mg orally three times a day for 7–10 days OR

- Acyclovir 200 mg orally five times a day for 7–10 days OR

- Valacyclovir 1 g orally twice a day for 7–10 days OR

- Famciclovir 250 mg orally three times a day for 7–10 days

Note: Treatment can be extended if healing is incomplete after 10 days of therapy.

Established herpes simplex virus type 2 Infection

Almost all persons with symptomatic first-episode genital herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection subsequently experience recurrent episodes of genital lesions; recurrences are less frequent after initial genital herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection. Intermittent asymptomatic shedding occurs in persons with genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection, even in those with longstanding or clinically silent infection. Antiviral therapy for recurrent genital herpes can be administered either as suppressive therapy to reduce the frequency of recurrences or episodically to ameliorate or shorten the duration of lesions. Some persons, including those with mild or infrequent recurrent outbreaks, benefit from antiviral therapy; therefore, options for treatment should be discussed. Many persons prefer suppressive therapy, which has the additional advantage of decreasing the risk for genital HSV-2 transmission to susceptible partners 23.

Suppressive therapy for recurrent genital herpes

Suppressive therapy reduces the frequency of genital herpes recurrences by 70%–80% in patients who have frequent recurrences 23; many persons receiving such therapy report having experienced no symptomatic outbreaks. Treatment also is effective in patients with less frequent recurrences. Safety and efficacy have been documented among patients receiving daily therapy with acyclovir for as long as 6 years and with valacyclovir or famciclovir for 1 year 24. Quality of life is improved in many patients with frequent recurrences who receive suppressive therapy rather than episodic treatment 25.

The frequency of genital herpes recurrences diminishes over time in many persons, potentially resulting in psychological adjustment to the disease. Therefore, periodically during suppressive treatment (e.g., once a year), providers should discuss the need to continue therapy. However, neither treatment discontinuation nor laboratory monitoring in a healthy person is necessary.

Treatment with valacyclovir 500 mg daily decreases the rate of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) transmission in discordant, heterosexual couples in which the source partner has a history of genital HSV-2 infection 26. Such couples should be encouraged to consider suppressive antiviral therapy as part of a strategy to prevent transmission, in addition to consistent condom use and avoidance of sexual activity during recurrences. Suppressive antiviral therapy also is likely to reduce transmission when used by persons who have multiple partners (including men who have sex with men) and by those who are HSV-2 seropositive without a history of genital herpes.

Recommended regimens

- Acyclovir 400 mg orally twice a day OR

- Valacyclovir 500 mg orally once a day* OR

- Valacyclovir 1 g orally once a day OR

- Famiciclovir 250 mg orally twice a day

*Valacyclovir 500 mg once a day might be less effective than other valacyclovir or acyclovir dosing regimens in persons who have very frequent recurrences (i.e., ≥10 episodes per year).

Acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir appear equally effective for episodic treatment of genital herpes 27, but famciclovir appears somewhat less effective for suppression of viral shedding 28. Ease of administration and cost also are important considerations for prolonged treatment.

Episodic therapy for recurrent genital herpes

Effective episodic treatment of recurrent herpes requires initiation of therapy within 1 day of lesion onset or during the prodrome that precedes some outbreaks. The patient should be provided with a supply of drug or a prescription for the medication with instructions to initiate treatment immediately when symptoms begin.

Recommended regimens

- Acyclovir 400 mg orally three times a day for 5 days OR

- Acyclovir 800 mg orally twice a day for 5 days OR

- Acyclovir 800 mg orally three times a day for 2 days OR

- Valacyclovir 500 mg orally twice a day for 3 days OR

- Valacyclovir 1 g orally once a day for 5 days OR

- Famciclovir 125 mg orally twice daily for 5 days OR

- Famciclovir 1 gram orally twice daily for 1 day OR

- Famciclovir 500 mg once, followed by 250 mg twice daily for 2 days

Severe disease

Intravenous (IV) acyclovir therapy should be provided for patients who have severe HSV disease or complications that necessitate hospitalization (e.g., disseminated infection, pneumonitis, or hepatitis) or central nervous system complications (e.g., meningoencephalitis). The recommended regimen is acyclovir 5–10 mg/kg IV every 8 hours for 2–7 days or until clinical improvement is observed, followed by oral antiviral therapy to complete at least 10 days of total therapy. HSV encephalitis requires 21 days of intravenous therapy. Impaired renal function warrants an adjustment in acyclovir dosage.

Management of sex partners

The sex partners of persons who have genital herpes can benefit from evaluation and counseling. Symptomatic sex partners should be evaluated and treated in the same manner as patients who have genital herpes. Asymptomatic sex partners of patients who have genital herpes should be questioned concerning histories of genital lesions and offered type-specific serologic testing for HSV infection.

HIV Infection

Immunocompromised patients can have prolonged or severe episodes of genital, perianal, or oral herpes. Lesions caused by HSV are common among persons with HIV infection and might be severe, painful, and atypical. HSV shedding is increased in persons with HIV infection. Whereas antiretroviral therapy reduces the severity and frequency of symptomatic genital herpes, frequent subclinical shedding still occurs 29. Clinical manifestations of genital herpes might worsen during immune reconstitution early after initiation of antiretroviral therapy.

Suppressive or episodic therapy with oral antiviral agents is effective in decreasing the clinical manifestations of HSV among persons with HIV infection 30. HSV type-specific serologic testing can be offered to persons with HIV infection during their initial evaluation if infection status is unknown, and suppressive antiviral therapy can be considered in those who have HSV-2 infection. Suppressive anti-HSV therapy in persons with HIV infection does not reduce the risk for either HIV transmission or HSV-2 transmission to susceptible sex partners 31.

Recommended regimens for daily suppressive therapy in persons with HIV

- Acyclovir 400–800 mg orally twice to three times a day OR

- Valacyclovir 500 mg orally twice a day OR

- Famciclovir 500 mg orally twice a day

Recommended regimens for episodic infection in persons with HIV

- Acyclovir 400 mg orally three times a day for 5–10 days OR

- Valacyclovir 1 g orally twice a day for 5–10 days OR

- Famciclovir 500 mg orally twice a day for 5–10 days

For severe HSV disease, initiating therapy with acyclovir 5–10 mg/kg IV every 8 hours might be necessary.

Antiviral resistant HSV

If lesions persist or recur in a patient receiving antiviral treatment, HSV resistance should be suspected and a viral isolate obtained for sensitivity testing 32. Such persons should be managed in consultation with an infectious-disease specialist, and alternate therapy should be administered. All acyclovir-resistant strains are also resistant to valacyclovir, and most are resistant to famciclovir. Foscarnet (40–80 mg/kg IV every 8 hours until clinical resolution is attained) is often effective for treatment of acyclovir-resistant genital herpes 33. Intravenous cidofovir 5 mg/kg once weekly might also be effective. Imiquimod is a topical alternative 34, as is topical cidofovir gel 1%; however, cidofovir must be compounded at a pharmacy 35. These topical preparations should be applied to the lesions once daily for 5 consecutive days.

Clinical management of antiviral resistance remains challenging among persons with HIV infection, necessitating other preventative approaches. However, experience with another group of immunocompromised persons (hematopoietic stem-cell recipients) demonstrated that persons receiving daily suppressive antiviral therapy were less likely to develop acyclovir-resistant HSV compared with those who received episodic therapy for outbreaks 36.

References- Richardson D, Goldmeier D. Lymphogranuloma venereum: an emerging cause of proctitis in men who have sex with men. Int J STD AIDS. 2007 Jan;18(1):11-4; quiz 15.

- Sheinman MD, Vinod J. Lymphogranuloma Venereum Proctocolitis. [Updated 2019 Jul 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544283

- Macdonald N, Sullivan AK, French P, White JA, Dean G, Smith A, Winter AJ, Alexander S, Ison C, Ward H. Risk factors for rectal lymphogranuloma venereum in gay men: results of a multicentre case-control study in the U.K. Sex Transm Infect. 2014 Jun;90(4):262-8.

- Pathela P, Blank S, Schillinger JA. Lymphogranuloma venereum: old pathogen, new story. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2007 Mar;9(2):143-50.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Summary of notifiable diseases, United States 1995. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 1996 Oct 25;44(53):1-87.

- Savage EJ, van de Laar MJ, Gallay A, van der Sande M, Hamouda O, Sasse A, Hoffmann S, Diez M, Borrego MJ, Lowndes CM, Ison C., European Surveillance of Sexually Transmitted Infections (ESSTI) network. Lymphogranuloma venereum in Europe, 2003-2008. Euro Surveill. 2009 Dec 03;14(48).

- Haar K, Dudareva-Vizule S, Wisplinghoff H, Wisplinghoff F, Sailer A, Jansen K, Henrich B, Marcus U. Lymphogranuloma venereum in men screened for pharyngeal and rectal infection, Germany. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2013 Mar;19(3):488-92.

- Martí-Pastor M, García de Olalla P, Barberá MJ, Manzardo C, Ocaña I, Knobel H, Gurguí M, Humet V, Vall M, Ribera E, Villar J, Martín G, Sambeat MA, Marco A, Vives A, Alsina M, Miró JM, Caylà JA., HIV Surveillance Group. Epidemiology of infections by HIV, Syphilis, Gonorrhea and Lymphogranuloma Venereum in Barcelona City: a population-based incidence study. BMC Public Health. 2015 Oct 05;15:1015.

- Dougan S, Evans BG, Elford J. Sexually transmitted infections in Western Europe among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Oct;34(10):783-90.

- Rönn MM, Ward H. The association between lymphogranuloma venereum and HIV among men who have sex with men: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011 Mar 18;11:70.

- Brenchley JM, Price DA, Douek DC. HIV disease: fallout from a mucosal catastrophe? Nat. Immunol. 2006 Mar;7(3):235-9.

- van Nieuwkoop C, Gooskens J, Smit VT, Claas EC, van Hogezand RA, Kroes AC, Kroon FP. Lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis: mucosal T cell immunity of the rectum associated with chlamydial clearance and clinical recovery. Gut. 2007 Oct;56(10):1476-7.

- Mazzarella, G; Paparo, F; Maglio, M; Troncone, R (2000). Organ culture of rectal mucosa : in vitro challenge with gluten in celiac disease. Methods Mol Med. 41. pp. 163–73. doi:10.1385/1-59259-082-9:163. ISBN 978-1-59259-082-7

- Soni, S; Srirajaskanthan, R; Lucas, SB; Alexander, S; Wong, T; White, JA (July 2010). “Lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis masquerading as inflammatory bowel disease in 12 homosexual men”. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 32 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04313.x

- de Vries HJ, van der Bij AK, Fennema JS, Smit C, de Wolf F, Prins M, Coutinho RA, Morré SA (2008). “Lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis in men who have sex with men is associated with anal enema use and high-risk behavior”. Sex Transm Dis. 35 (2): 203–8. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815abb08

- Nowak-Węgrzyn A (2015). “Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome and allergic proctocolitis”. Allergy Asthma Proc. 36 (3): 172–84. doi:10.2500/aap.2015.36.3811

- Hauer-Jensen M, Denham JW, Andreyev HJ (2014). “Radiation enteropathy–pathogenesis, treatment and prevention”. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 11 (8): 470–9.

- Klausner JD, Kohn R, Kent C. Etiology of clinical proctitis among men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:300–2.

- Proctitis, Proctocolitis, and Enteritis. 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/proctitis.htm

- McLean CA, Stoner BP, Workowski KA. Treatment of lymphogranuloma venereum. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44(Suppl 3):S147–52.

- Aoki FY, Tyring S, Diaz-Mitoma F, et al. Single-day, patient-initiated famciclovir therapy for recurrent genital herpes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:8–13.

- Genital HSV Infections. 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/herpes.htm

- Romanowski B, Marina RB, Roberts JN, et al. Patients’ preference of valacyclovir once-daily suppressive therapy versus twice-daily episodic therapy for recurrent genital herpes: a randomized study. Sex Transm Dis 2003;30:226–31.

- Fife KH, Crumpacker CS, Mertz GJ, et al. Acyclovir Study Group. Recurrence and resistance patterns of herpes simplex virus following cessation of ≥6 years of chronic suppression with acyclovir. J Infect Dis 1994;169:1338–41.

- Bartlett BL, Tyring SK, Fife K, et al. Famciclovir treatment options for patients with frequent outbreaks of recurrent genital herpes: the RELIEF trial. J Clin Virol 2008;43:190–5.

- Corey L, Wald A, Patel R, et al. Once-daily valacyclovir to reduce the risk of transmission of genital herpes. N Engl J Med 2004;350:11–20.

- Chosidow O, Drouault Y, Leconte-Veyriac F, et al. Famciclovir vs. aciclovir in immunocompetent patients with recurrent genital herpes infections: a parallel-groups, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Br J Dermatol 2001;144:818–24.

- Wald A, Selke S, Warren T, et al. Comparative efficacy of famciclovir and valacyclovir for suppression of recurrent genital herpes and viral shedding. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33:529–33.

- Tobian AA, Grabowski MK, Serwadda D, et al. Reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 2 after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2013;208:839–46.

- DeJesus E, Wald A, Warren T, et al. Valacyclovir for the suppression of recurrent genital herpes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. J Infect Dis 2003;188:1009–16.

- Mujugira A, Magaret AS, Celum C, et al. Daily acyclovir to decrease herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) transmission from HSV-2/HIV-1 coinfected persons: a randomized controlled trial. J Infect Dis 2013;208:1366–74.

- Reyes M, Shaik NS, Graber JM, et al. Acyclovir-resistant genital herpes among persons attending sexually transmitted disease and human immunodeficiency virus clinics. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:76–80.

- Levin MJ, Bacon TH, Leary JJ. Resistance of herpes simplex virus infections to nucleoside analogues in HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39(Suppl 5):S248–57.

- Perkins N, Nisbet M, Thomas M. Topical imiquimod treatment of aciclovir-resistant herpes simplex disease: case series and literature review. Sex Transm Infect 2011;87:292–5.

- McElhiney LF. Topical cidofovir for treatment of resistant viral infections. Int J Pharm Compd 2006;10:324–8.

- Erard V, Wald A, Corey L, et al. Use of long-term suppressive acyclovir after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: impact on herpes simplex virus (HSV) disease and drug-resistant HSV disease. J Infect Dis 2007;196:266–70.