Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is cancer of the prostate gland in the male reproductive system. The prostate gland makes seminal fluid that is part of the semen. Just behind the prostate are glands called seminal vesicles that make most of the fluid for semen. The prostate gland lies just below the bladder (the organ that collects and empties urine) and in front of the rectum (the lower part of the intestine), just above the pelvic floor (see Figure 1). The prostate gland is about the size of a walnut and surrounds part of the urethra (the tube that empties urine from the bladder). Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among older men (after skin cancer), but it can often be treated successfully 1. Other than skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer in American men (more common in older men than younger men) 2. In the U.S., about 1 out of 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer during his lifetime. Prostate cancer is more likely to develop in older men and in non-Hispanic Black men. About 6 cases in 10 are diagnosed in men who are 65 or older, and it is rare in men under 40. The average age of men at diagnosis is about 66.

Many men with prostate cancer never experience symptoms and, without prostate cancer screening, would never know they have the disease 3. In autopsy studies of men who died of other causes, more than 20% of men aged 50 to 59 years and more than 33% of men aged 70 to 79 years were found to have prostate cancer 4. In some men, prostate cancer is more aggressive and leads to death. The median age of death from prostate cancer is 80 years, and more than two-thirds of all men who die of prostate cancer are older than 75 years 5. African American men have an increased lifetime risk of prostate cancer death compared with those of other races/ethnicities (4.2% for African American men, 2.9% for Hispanic men, 2.3% for white men, and 2.1% for Asian and Pacific Islander men) 5.

The American Cancer Society’s estimates for prostate cancer in the United States for 2022 are 5:

- About 268,490 new cases of prostate cancer

- About 34,500 deaths from prostate cancer

- The rate of new cases of prostate cancer was 112.7 per 100,000 men per year based on 2015–2019 cases, age-adjusted.

- In general prostate cancer has excellent survival rates, but death rates are higher in African American men, men who have advanced stage cancer, and men who are between the ages of 75 and 84.

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 96.8%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 5.7%. Prostate cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death in the United States. The death rate was 18.9 per 100,000 men per year based on 2015–2019, age-adjusted.

- In 2019, there were an estimated 3,253,416 men living with prostate cancer in the United States.

Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in American men, behind only lung cancer 6. About 1 man in 41 will die of prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer can be a serious disease, but most men diagnosed with prostate cancer do not die from it. In fact, more than 3.1 million men in the United States who have been diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point are still alive today 6.

Prostate cancer begins when cells in the prostate gland start to grow uncontrollably. The prostate is a gland found only in males. It makes some of the fluid that is part of semen.

In men, the prostate gland can be felt by digital palpation during a rectal examination.The size of the prostate changes with age. In younger men, it is about the size of a walnut, but it can be much larger in older men.

Just behind the prostate are glands called seminal vesicles that make most of the fluid for semen. The urethra, which is the tube that carries urine and semen out of the body through the penis, goes through the center of the prostate.

Your prostate cancer treatment options depend on several factors including how big the cancer is, how fast your cancer is growing and whether it has spread anywhere else in your body (also known as the stage), the type of prostate cancer, how abnormal the cells look under a microscope (the grade) and your general health and level of fitness as well as the potential benefits or side effects of the treatment. These are all things to think about when making decisions about treatment. A team of doctors and other professionals will discuss the best treatment and care for you.

The main treatments for prostate cancer are:

- active surveillance or watchful waiting

- surgery

- external radiotherapy

- internal radiotherapy (brachytherapy)

- hormone therapy

- high frequency ultrasound therapy (HIFU) (as part of a clinical trial)

- cryotherapy (as part of a clinical trial)

- chemotherapy in combination with other treatments

- immunotherapy

- targeted therapy

- symptom control treatment

You have one or more of these treatments depending on the stage of your cancer.

Your doctors and nurses will tell you what your options are and help you make the decision about your treatment.

Can I lower the risk of prostate cancer progressing or coming back?

If you have (or have had) prostate cancer, you probably want to know if there are things you can do that might lower your risk of the cancer growing or coming back, such as exercising, eating a certain type of diet, or taking nutritional supplements. While there are some things you can do that might be helpful, more research is needed to know for sure.

- Get regular physical activity. Some research has suggested that men who exercise regularly after treatment might be less likely to die from their prostate cancer than those who don’t. It’s not clear exactly how much activity might be needed, but more seems to be better. More vigorous activity might also be more helpful than less vigorous activity. Further studies are needed to follow up on these findings.

- Quit smoking. Some research has suggested that men who smoke are more likely to have their prostate cancer recur and are more likely to die from it than men who don’t smoke. More research is needed to see if quitting smoking can help lower these risks, although quitting is already known to have a number of other health benefits.

- Nutrition and dietary supplements. Some studies have linked eating a diet that is high in added sugars, meat, and fat to a higher chance of dying from prostate cancer. But eating a “Mediterranean” diet pattern with foods such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, has been associated with a lower chance of dying. So eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables and lower in animal fats might be helpful, but more research is needed to be sure. We do know that a healthy diet can have positive effects on your overall health, with benefits that extend beyond your risk of prostate or other cancers. So far, no dietary supplements have been shown to clearly help lower the risk of prostate cancer progressing or coming back. In fact, some research has suggested that some supplements, such as selenium, might even be harmful. This doesn’t mean that no supplements will help, but it’s important to know that none have been proven to do so. Dietary supplements are not regulated like medicines in the United States – they do not have to be proven effective (or even safe) before being sold, although there are limits on what they’re allowed to claim they can do. If you are thinking about taking any type of nutritional supplement, talk to your health care team. They can help you decide which ones you can use safely while avoiding those that could be harmful.

Can I lower my risk of getting a second cancer?

Prostate cancer survivors can be affected by a number of health problems, but often a major concern is facing cancer again. Cancer that comes back after treatment is called a recurrence. But some cancer survivors may develop a new, unrelated cancer later. This is called a second cancer.

Unfortunately, being treated for prostate cancer doesn’t mean you can’t get another cancer. Men who have had prostate cancer can still get the same types of cancers that other men get. In fact, they might be at higher risk for certain types of cancer.

Men who have had prostate cancer can get any type of second cancer, but they have an increased risk of certain cancers, including:

- Small intestine cancer

- Soft tissue cancer

- Bladder cancer

- Thyroid cancer

- Thymus cancer

- Melanoma of the skin

Men who are treated with radiation therapy also have a higher risk of:

- Rectal cancer

- Acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

This risk is probably related to the dose of radiation. Newer methods of giving radiation therapy may have different effects on the risks of a second cancer. Because these methods are newer, the long-term effects have not been studied as well.

There are steps you can take to lower your risk and stay as healthy as possible. For example, prostate cancer survivors should do their best to stay away from all tobacco products and tobacco smoke. Smoking can increase the risk of bladder cancer, as well as increase the risk of many other cancers.

To help maintain good health, prostate cancer survivors should also:

- Get to and stay at a healthy weight

- Keep physically active and limit the time you spend sitting or lying down

- Follow a healthy eating pattern that includes plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and limits or avoids red and processed meats, sugary drinks, and highly processed foods

- Not drink alcohol. If you do drink, have no more than 1 drink per day for women or 2 per day for men

These steps may also lower the risk of some other health problems.

Prostate gland

The prostate is a gland found only in men, which forms an important part of the male reproductive system. The prostate gland secretes a fluid that keeps sperm alive and healthy and that forms part of semen.

The prostate gland is located at the base of the bladder. It is about the size of a walnut but gets bigger as men get older. The prostate gland measures about 2 × 4 × 3 cm and is an aggregate of 30 to 50 compound tubuloacinar glands enclosed in a single fibrous capsule. These glands empty through about 20 pores in the urethral wall. The stroma of the prostate consists of connective tissue and smooth muscle, like that of the seminal vesicles. The thin, milky secretion of the prostate constitutes about 30% of the semen.

The prostate is a chestnut-shaped structure that surrounds the urethra (first part of the tube that carries urine from the bladder to the penis) and ejaculatory ducts. The urethra also carries semen, which is the fluid containing sperm. The prostate is found behind the base of the penis and immediately underneath the urinary bladder.

The prostate gland produces a protein called prostate specific antigen (PSA). A blood test can measure the level of PSA.

The prostate slowly increases in size from birth to puberty. It then expands rapidly until about age 30, after which time its size typically remains stable until about age 40-45, when further enlargement may occur, constricting the urethra and interfering with urine flow.

In addition to its susceptibility to prostate cancer and tumors, the prostate is also subject to infection in sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Prostatitis, inflammation of the prostate, is the single most common reason that men consult a urologist.

Figure 1. Normal prostate gland

Normal PSA levels

PSA also callled Prostate-Specific Antigen, is a type of protein produced by cells in the prostate gland and found in the blood. Results are usually expressed as nanograms of PSA per milliliter (ng/mL) of blood. Normally, PSA is produced and released within the prostate gland, where it participates in the dissolution of the seminal fluid coagulum and plays an important role in fertility. Healthy prostates create low levels of PSA and only small amounts of PSA move out of the prostate and into the blood. PSA blood levels may be higher than normal in men who have prostate cancer, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), or infection or inflammation of the prostate gland (prostatitis).

The PSA test uses a blood sample to measure a person’s PSA level. In some patients, the PSA test may be used for prostate cancer screening. The PSA test is also used to help with the diagnostic process for prostate cancer and noncancerous prostate conditions, as well as to monitor people who have been diagnosed with these conditions.

The PSA test result cannot diagnose prostate cancer. Only a prostate biopsy can diagnose prostate cancer.

There is no specific normal or abnormal level of PSA in the blood. In the past, PSA levels of 4.0 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL) and lower were considered normal, but this varies by age. However, some individuals with PSA levels below 4.0 ng/mL have prostate cancer and many with higher PSA levels between 4 and 10 ng/mL do not have prostate cancer 7.

In addition, various factors can cause someone’s PSA level to fluctuate. For example, the PSA level tends to increase with age, prostate gland size, and inflammation or infection. A recent prostate biopsy will also increase the PSA level, as can ejaculation or vigorous exercise (such as cycling) in the 2 days before testing. Conversely, some drugs—including finasteride and dutasteride, which are used to treat BPH—lower the PSA level.

In general, however, the higher a man’s PSA level, the more likely it is that he has prostate cancer.

PSA test result meaning:

- For men in their 50s or younger, a PSA level should be below 2.5 ng/mL in most cases.

- Older men often have slightly higher PSA levels than younger men.

- When total prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concentration is below 2.0 ng/mL, the probability of prostate cancer in asymptomatic men is low. When total PSA concentration is above 10.0 ng/mL, the probability of cancer is high and prostate biopsy is generally recommended.

- The total PSA range of 4.0 to 10.0 ng/mL has been described as a diagnostic “gray zone,” in which the free PSA/total PSA ratio helps to determine the relative risk of prostate cancer (see Table 2 below). Therefore, some urologists recommend using the free PSA/total ratio to help select which men should undergo biopsy. However, even a negative result of prostate biopsy does not rule-out prostate cancer (see Table 3). Up to 20% of men with negative biopsy results have subsequently been found to have prostate cancer.

Table 1. Total PSA reference values

| Age (years) | PSA upper limit (ng/mL) |

|---|---|

| <40 | < or =2.0 |

| 40-49 | < or =2.5 |

| 50-59 | < or =3.5 |

| 60-69 | < or =4.5 |

| 70-79 | < or =6.5 |

| 80+ | < or =7.2 |

Table 2. When total PSA concentration is in the range of 4.0-10.0 ng/mL

| Probability of cancer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Free PSA/total PSA ratio | 50-59 years | 60-69 years | > or =70 years |

| < or =0.10 | 49% | 58% | 65% |

| 0.11-0.18 | 27% | 34% | 41% |

| 0.19-0.25 | 18% | 24% | 30% |

| >0.25 | 9% | 12% | 16% |

Table 3. Based on free PSA/total PSA ratio, the percent probability of finding prostate cancer on a needle biopsy by age in years

| Free PSA/total PSA ratio | 50-59 years | 60-69 years | 70 years and older |

|---|---|---|---|

| < or =0.10 | 49.00% | 58.00% | 65.00% |

| 0.11-0.18 | 27.00% | 34.00% | 41.00% |

| 0.19-0.25 | 18.00% | 24.00% | 30.00% |

| >0.25 | 9.00% | 12.00% | 16.00% |

PSA testing

Since PSA levels in the blood have been linked with prostate cancer, many doctors have used repeated PSA tests in the hope of finding “early” prostate cancer in men with no symptoms of the disease. Unfortunately, PSA is not as useful for screening as many have hoped because many men with prostate cancer do not have high PSA levels, and other conditions that are not cancer (such as benign prostate hyperplasia) can also increase PSA levels 9. Research has shown that men who receive PSA testing are less likely to die specifically from prostate cancer. However when accounting for deaths from all causes, no lives are saved, meaning that men who receive PSA screening have not been shown to live longer than men who do not have PSA screening. Men with medical conditions that limit their life expectancy to less than 10 years are unlikely to benefit from PSA screening as their probability of dying from the underlying medical problem is greater than the chance of dying from asymptomatic prostate cancer.

A doctor may order a PSA test for several reasons:

- Prostate cancer screening: Cancer screening checks for cancer in people who don’t have symptoms. People with prostate cancer often have elevated levels of PSA in their blood, but elevated levels are also found in people without prostate cancer. The decision about whether or not to use a PSA test to screen for prostate cancer is highly individualized based on a patient’s risk factors and health history. Patients should work with their doctor to understand the risks and benefits of PSA screening for their specific situation.

- Prostate disease diagnosis: If you have symptoms of a prostate condition, or if your prostate gland is not normal during a physical exam, your doctor may recommend a PSA test. An elevated level of PSA may indicate an issue in the prostate such as prostate cancer, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), or inflammation of the prostate. This then may lead to more follow-up testing to determine the diagnosis.

- Prostate cancer or disease monitoring and follow-up: If you’ve been diagnosed with prostate cancer or BPH, your doctor may order PSA tests to monitor the effects of treatment. For those who have completed treatment for prostate cancer, the PSA test can be used to check for signs that the cancer has come back.

Your doctor might use other ways of interpreting PSA results before deciding whether to order a biopsy to test for cancerous tissue. These other methods are intended to improve the accuracy of the PSA test as a screening tool. Researchers continue to investigate variations of the PSA test to determine whether they provide a measurable benefit.

Variations of the PSA test include:

- PSA velocity. PSA velocity is the change in PSA levels over time. A rapid rise in PSA may indicate the presence of cancer or an aggressive form of cancer. However, recent studies have cast doubt on the value of PSA velocity in predicting a finding of prostate cancer from biopsy.

- Percentage of free PSA. PSA circulates in the blood in two forms — either attached to certain blood proteins or unattached (free). If you have a high PSA level but a low percentage of free PSA, it may be more likely that you have prostate cancer.

- PSA density. Prostate cancers can produce more PSA per volume of tissue than benign prostate conditions can. PSA density measurements adjust PSA values for prostate volume. Measuring PSA density generally requires an MRI or transrectal ultrasound.

What do experts recommend?

Most medical organizations encourage men aged 55 to 69 years to discuss the pros and cons of prostate cancer screening with their doctors 10. The discussion should include a review of your risk factors and your preferences about screening. You might consider starting the discussions sooner if you’re black, have a family history of prostate cancer or have other risk factors.

If you choose to have prostate cancer screening, most organizations recommend stopping around age 70 or if you develop other serious medical conditions that limit your life expectancy 10. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends against screening for prostate cancer in men aged 70 years or older 10. The USPSTF also concludes that at present, the balance between the benefits and the drawbacks of prostate cancer screening in men younger than age 70 years cannot be assessed, because the available evidence is insufficient 11.

If someone who has no symptoms of prostate cancer chooses to undergo prostate cancer screening and is found to have an elevated PSA level, the doctor may recommend another PSA test to confirm the original finding. If the PSA level is still high, the doctor may recommend that the person continue with PSA tests and digital rectal exams (DREs) at regular intervals to watch for any changes over time also called observation or watchful waiting.

If the PSA level continues to rise or a suspicious lump is detected during a digital rectal exam, the doctor may recommend additional tests to determine the nature of the problem. These may include imaging tests, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or high-resolution micro-ultrasound.

Alternatively, the doctor may recommend a prostate biopsy. During this procedure, multiple samples of prostate tissue are collected by inserting hollow needles into the prostate and then withdrawing them. The biopsy needle may be inserted through the wall of the rectum (transrectal biopsy) or through the perineum (transperineal biopsy). A pathologist then examines the collected tissue under a microscope. Although both biopsy techniques are guided by ultrasound imaging so the doctor can view the prostate during the biopsy procedure, ultrasound cannot be used alone to diagnose prostate cancer. An MRI-guided biopsy may be performed for patients with suspicious areas seen on MRI.

In the past, men with elevated PSA levels and no other symptoms were sometimes prescribed antibiotics to see if an infection might be causing the PSA increase. However, according to the American Urological Association, there is no evidence to support the use of antibiotics to reduce PSA levels in men who are not experiencing other symptoms.

Table 4. Benefits and Harms of PSA Screening in Men 55 to 69 Years of Age

| Outcome | Incidence per 1,000 men who undergo PSA screening every 1 to 4 years for 10 years | Incidence per 1,000 men who do not undergo PSA screening | Benefit or harm of PSA screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Die of prostate cancer | 4 or 5 | 5 | 0 or 1 fewer prostate cancer death |

| Die of any cause | 200 | 200 | No difference |

| Still alive after 10 years | 800 | 800 | No difference |

| False-positive results | 100 to 120 | 0 | 100 to 120 more false-positive results (may cause anxiety; most lead to biopsy) |

| Additional prostate cancer diagnoses | 110 | 0 | 110 additional prostate cancer diagnoses (about 90% receive treatment) |

| Erectile dysfunction due to treatment | 29 | 0 | 29 more men with erectile dysfunction |

| Urinary incontinence due to treatment | 18 | 0 | 18 more men with urinary incontinence |

| Cardiovascular events due to treatment | 2 | 0 | 2 additional cardiovascular events |

| Deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolus due to treatment | 1 | 0 | 1 additional deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolus |

Abbreviations: DVT = deep venous thrombosis; PE = pulmonary embolus; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

[Source 12 ]PSA testing disadvantages

You may wonder how getting a test for prostate cancer could have a downside. After all, there’s little risk involved in the test itself — it requires simply drawing blood for evaluation in a lab.

However, there are some potential downsides once the PSA results are in. These include:

- Elevated PSA levels can have other causes, such as benign prostate enlargement (benign prostatic hyperplasia) or prostate infection (prostatitis). Also, PSA levels normally increase with age. These false-positives are common.

- Some prostate cancers may not produce much PSA. And it’s possible to have prostate cancer and also have a normal PSA level. It’s possible to have what’s known as a “false-negative” — a test result that incorrectly indicates you don’t have prostate cancer when you do.

- Certain drugs used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or urinary conditions, and large doses of certain chemotherapy medications, may lower PSA levels. Obesity also can lower PSA levels.

- Overdiagnosis. Some prostate cancers detected by PSA tests will never cause symptoms or lead to death. These symptom-free cancers are considered overdiagnoses — identification of cancer not likely to cause poor health or to present a risk of death.

- Follow-up tests to check out the cause of an elevated PSA test can be invasive, stressful, expensive or time-consuming.

- Living with a slow-growing prostate cancer that doesn’t need treatment might cause stress and anxiety.

PSA screening for prostate cancer may reduce risk of prostate cancer mortality but is associated with harms including false-positive results, biopsy complications, and overdiagnosis in 20 percent to 50 percent of screen-detected prostate cancers 13. Early, active treatment for screen-detected prostate cancer may reduce the risk of metastatic disease, although the long-term impact of early, active treatment on prostate cancer mortality remains unclear. Active treatments for prostate cancer are frequently associated with sexual and urinary difficulties.

What have randomized trials of prostate cancer screening found?

Several large, randomized trials of prostate cancer screening have been carried out. One of the largest is the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial, to determine whether certain screening tests can help reduce the numbers of deaths from several common cancers 14. In the prostate portion of the trial, the PSA test and digital rectal exam were evaluated for their ability to decrease a man’s chances of dying from prostate cancer.

The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) investigators found that men who underwent annual prostate cancer screening had a higher incidence of prostate cancer than men in the control group but had about the same rate of deaths from the disease 14. Overall, the results suggest that many men were treated for prostate cancers that would not have been detected in their lifetime without screening. Consequently, these men were exposed unnecessarily to the potential harms of treatment.

A second large trial, the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC), compared prostate cancer deaths in men randomly assigned to PSA-based screening or no screening 15, 16. As in the PLCO, men in European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) who were screened for prostate cancer had a higher incidence of the disease than control men. In contrast to the PLCO, however, men who were screened had a lower rate of death from prostate cancer 15, 16.

A subsequent analysis of data from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial used a statistical model to account for the fact that some men in the PLCO trial who were assigned to the control group had nevertheless undergone PSA screening. This analysis suggested that the level of benefit in the PLCO and ERSPC trials was similar and that both trials showed some reduction in prostate cancer death in association with prostate cancer screening 17. Such statistical modeling studies have important limitations and rely on unverified assumptions that can render their findings questionable (or more suitable for further study than to serve as a basis for screening guidelines). More important, the model could not provide an assessment of the balance of benefits versus harms from screening.

The third and largest trial, the Cluster Randomized Trial of PSA Testing for Prostate Cancer (CAP), conducted in the United Kingdom, compared prostate cancer mortality among men whose primary care practices were randomly assigned to offer their patients a single PSA screening test or to provide usual care in which screening was not offered 18. After a median follow-up of 10 years, more low-risk prostate cancers were detected in the single PSA test group than in the usual (unscreened) care group (even though only about a third of men in the screening group actually had the PSA test), but there was no difference in prostate cancer mortality 18.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of all randomized controlled trials comparing PSA screening with usual care in men without a diagnosis of prostate cancer concluded that PSA screening for prostate cancer leads to a small reduction in prostate cancer mortality over 10 years but does not affect overall mortality 19.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force has estimated that, for every 1,000 men ages 55 to 69 years who are screened for 13 years 11:

- About 1.3 deaths from prostate cancer would be avoided (or 1 death avoided per 769 men screened). However, based on 3 additional years of follow-up in the ERSPC trial, about 1.8 deaths from prostate cancer would be avoided per every 1,000 men screened, or 1 death in 570 men screened 20.

- 3 men would avoid developing metastatic cancer

- 5 men would die from prostate cancer despite screening, diagnosis, and treatment

- 240 men would have a positive PSA test result, many of whom would have a biopsy that shows that the result was a false-positive; some men who had a biopsy would experience at least moderately bothersome symptoms (pain, bleeding, or infection) from the procedure (and 2 would be hospitalized).

- 100 men would be diagnosed with prostate cancer. Of those, 80 would be treated (either immediately or after a period of active surveillance) with surgery or radiation. Many of these men would have a serious complication from treatment, with 50 experiencing sexual dysfunction and 15 experiencing urinary incontinence.

- 200 men would die of causes other than prostate cancer

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

An enlarged prostate is also called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) 21. Most men will have enlarged prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia) as they get older. Symptoms often start after age 50.

In 2010, as many as 14 million men in the United States had lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia 22. Although benign prostatic hyperplasia rarely causes symptoms before age 40, the occurrence and symptoms increase with age. Benign prostatic hyperplasia affects about 50 percent of men between the ages of 51 and 60 and up to 90 percent of men older than 80 23.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is not cancer, and it does not seem to increase your chance of getting prostate cancer 21. But the early symptoms are the same. Check with your doctor if you have:

- A frequent and urgent need to urinate, especially at night

- Trouble starting a urine stream or making more than a dribble

- A urine stream that is weak, slow, or stops and starts several times

- The feeling that you still have to go, even just after urinating

- Small amounts of blood in your urine

Severe benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) can cause serious problems over time. Untreated, prostate gland enlargement can block the flow of urine out of the bladder and cause bladder, urinary tract or kidney problems. If it is found early, you are less likely to develop these problems.

Tests for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) include a digital rectal exam, blood and imaging tests, a urine flow study, and examination with a scope called a cystoscope. Treatments include watchful waiting, medicines, nonsurgical procedures, and surgery.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia symptoms

The severity of symptoms in people who have prostate gland enlargement varies, but symptoms tend to gradually worsen over time. Common signs and symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia include:

- Frequent or urgent need to urinate

- Increased frequency of urination at night (nocturia)

- Difficulty starting urination

- Weak urine stream or a stream that stops and starts

- Dribbling at the end of urination

- Straining while urinating

- Inability to completely empty the bladder

Less common signs and symptoms include:

- Urinary tract infection

- Inability to urinate

- Blood in the urine

The size of your prostate doesn’t necessarily mean your symptoms will be worse. Some men with only slightly enlarged prostates can have significant symptoms, while other men with very enlarged prostates can have only minor urinary symptoms.

In some men, symptoms eventually stabilize and might even improve over time.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia causes

The prostate gland is located beneath your bladder. The tube that transports urine from the bladder out of your penis (urethra) passes through the center of the prostate. When the prostate enlarges, it begins to block urine flow.

Most men have continued prostate growth throughout life. In many men, this continued growth enlarges the prostate enough to cause urinary symptoms or to significantly block urine flow.

It isn’t entirely clear what causes the prostate to enlarge. However, it might be due to changes in the balance of sex hormones as men grow older.

Risk factors for benign prostatic hyperplasia

Risk factors for prostate gland enlargement include:

- Aging. Prostate gland enlargement rarely causes signs and symptoms in men younger than age 40. About one-third of men experience moderate to severe symptoms by age 60, and about half do so by age 80.

- Family history. Having a blood relative, such as a father or brother, with prostate problems means you’re more likely to have problems.

- Ethnic background. Prostate enlargement is less common in Asian men than in white and black men. Black men might experience symptoms at a younger age than white men.

- Diabetes and heart disease. Studies show that diabetes, as well as heart disease and use of beta blockers, might increase the risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia.

- Lifestyle. Obesity increases the risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia, while exercise can lower your risk.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia complications

Complications of enlarged prostate can include:

- Sudden inability to urinate (urinary retention). You might need to have a tube (catheter) inserted into your bladder to drain the urine. Some men with an enlarged prostate need surgery to relieve urinary retention.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs). Inability to fully empty the bladder can increase the risk of infection in your urinary tract. If UTIs occur frequently, you might need surgery to remove part of the prostate.

- Bladder stones. These are generally caused by an inability to completely empty the bladder. Bladder stones can cause infection, bladder irritation, blood in the urine and obstruction of urine flow.

- Bladder damage. A bladder that hasn’t emptied completely can stretch and weaken over time. As a result, the muscular wall of the bladder no longer contracts properly, making it harder to fully empty your bladder.

- Kidney damage. Pressure in the bladder from urinary retention can directly damage the kidneys or allow bladder infections to reach the kidneys.

Most men with an enlarged prostate don’t develop these complications. However, acute urinary retention and kidney damage can be serious health threats.

Having an enlarged prostate doesn’t affect your risk of developing prostate cancer.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia diagnosis

Your doctor will start by asking detailed questions about your symptoms and doing a physical exam. This initial exam is likely to include:

- Digital rectal exam. The doctor inserts a finger into the rectum to check your prostate for enlargement.

- Urine test. Analyzing a sample of your urine can help rule out an infection or other conditions that can cause similar symptoms.

- Blood test. The results can indicate kidney problems.

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test. PSA is a substance produced in your prostate. PSA levels increase when you have an enlarged prostate. However, elevated PSA levels can also be due to recent procedures, infection, surgery or prostate cancer.

- Neurological exam. This brief evaluation of your mental functioning and nervous system can help identify causes of urinary problems other than enlarged prostate.

After that, your doctor might recommend additional tests to help confirm an enlarged prostate and to rule out other conditions. These additional tests might include:

- Urinary flow test. You urinate into a receptacle attached to a machine that measures the strength and amount of your urine flow. Test results help determine over time if your condition is getting better or worse.

- Postvoid residual volume test. This test measures whether you can empty your bladder completely. The test can be done using ultrasound or by inserting a catheter into your bladder after you urinate to measure how much urine is left in your bladder.

- 24-hour voiding diary. Recording the frequency and amount of urine might be especially helpful if more than one-third of your daily urinary output occurs at night.

If your condition is more complex, your doctor may recommend:

- Transrectal ultrasound. An ultrasound probe is inserted into your rectum to measure and evaluate your prostate.

- Prostate biopsy. Transrectal ultrasound guides needles used to take tissue samples (biopsies) of the prostate. Examining the tissue can help your doctor diagnose or rule out prostate cancer.

- Urodynamic and pressure flow studies. A catheter is threaded through your urethra into your bladder. Water — or, less commonly, air — is slowly injected into your bladder. Your doctor can then measure bladder pressure and determine how well your bladder muscles are working.

- Cystoscopy. A lighted, flexible cystoscope is inserted into your urethra, allowing your doctor to see inside your urethra and bladder. You will be given a local anesthetic before this test.

- Intravenous pyelogram or CT urogram. A tracer is injected into a vein. X-rays or CT scans are then taken of your kidneys, bladder and the tubes that connect your kidneys to your bladder (ureters). These tests can help detect urinary tract stones, tumors or blockages above the bladder.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia treatment

A wide variety of treatments are available for enlarged prostate, including medication, minimally invasive therapies and surgery. The best treatment choice for you depends on several factors, including:

- The size of your prostate

- Your age

- Your overall health

- The amount of discomfort or bother you are experiencing

If your symptoms are tolerable, you might decide to postpone treatment and simply monitor your symptoms. For some men, symptoms can ease without treatment.

Medication

Medication is the most common treatment for mild to moderate symptoms of prostate enlargement. The options include:

- Alpha blockers. These medications relax bladder neck muscles and muscle fibers in the prostate, making urination easier. Alpha blockers — which include alfuzosin (Uroxatral), doxazosin (Cardura), tamsulosin (Flomax), and silodosin (Rapaflo) — usually work quickly in men with relatively small prostates. Side effects might include dizziness and a harmless condition in which semen goes back into the bladder instead of out the tip of the penis (retrograde ejaculation).

- 5-alpha reductase inhibitors. These medications shrink your prostate by preventing hormonal changes that cause prostate growth. These medications — which include finasteride (Proscar) and dutasteride (Avodart) — might take up to six months to be effective. Side effects include retrograde ejaculation.

- Combination drug therapy. Your doctor might recommend taking an alpha blocker and a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor at the same time if either medication alone isn’t effective.

- Tadalafil (Cialis). Studies suggest this medication, which is often used to treat erectile dysfunction, can also treat prostate enlargement. However, this medication is not routinely used for enlarged prostate and is generally prescribed only to men who also experience erectile dysfunction.

Minimally invasive or surgical therapy

Minimally invasive or surgical therapy might be recommended if:

- Your symptoms are moderate to severe

- Medication hasn’t relieved your symptoms

- You have a urinary tract obstruction, bladder stones, blood in your urine or kidney problems

- You prefer definitive treatment

Minimally invasive or surgical therapy might not be an option if you have:

- An untreated urinary tract infection

- Urethral stricture disease

- A history of prostate radiation therapy or urinary tract surgery

- A neurological disorder, such as Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis

Any type of prostate procedure can cause side effects. Depending on the procedure you choose, complications might include:

- Semen flowing backward into the bladder instead of out through the penis during ejaculation

- Temporary difficulty with urination

- Urinary tract infection

- Bleeding

- Erectile dysfunction

- Very rarely, loss of bladder control (incontinence)

There are several types of minimally invasive or surgical therapy.

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)

A lighted scope is inserted into your urethra, and the surgeon removes all but the outer part of the prostate. TURP generally relieves symptoms quickly, and most men have a stronger urine flow soon after the procedure. After TURP you might temporarily need a catheter to drain your bladder, and you’ll be able to do only light activity until you’ve healed.

Transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP)

A lighted scope is inserted into your urethra, and the surgeon makes one or two small cuts in the prostate gland — making it easier for urine to pass through the urethra. This surgery might be an option if you have a small or moderately enlarged prostate gland, especially if you have health problems that make other surgeries too risky.

Transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT)

Your doctor inserts a special electrode through your urethra into your prostate area. Microwave energy from the electrode destroys the inner portion of the enlarged prostate gland, shrinking it and easing urine flow. This surgery is generally used only on small prostates in special circumstances because re-treatment might be necessary.

Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA)

In this outpatient procedure, a scope is passed into your urethra, allowing your doctor to place needles into your prostate gland. Radio waves pass through the needles, heating and destroying excess prostate tissue that’s blocking urine flow.

This procedure might be a good choice if you bleed easily or have certain other health problems. However, like TUMT, TUNA might only partially relieve your symptoms and it might take some time before you notice results.

Laser therapy

A high-energy laser destroys or removes overgrown prostate tissue. Laser therapy generally relieves symptoms right away and has a lower risk of side effects than does nonlaser surgery. Laser therapy might be used in men who shouldn’t have other prostate procedures because they take blood-thinning medications.

The options for laser therapy include:

- Ablative procedures. These procedures vaporize obstructive prostate tissue to increase urine flow. Examples include photoselective vaporization of the prostate (PVP) and holmium laser ablation of the prostate (HoLAP). Ablative procedures can cause irritating urinary symptoms after surgery, so in rare situations another resection procedure might be needed at some point.

- Enucleative procedures. Enucleative procedures, such as holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP), generally remove all the prostate tissue blocking urine flow and prevent regrowth of tissue. The removed tissue can be examined for prostate cancer and other conditions. These procedures are similar to open prostatectomy.

Prostate lift

In this experimental transurethral procedure, special tags are used to compress the sides of the prostate to increase the flow of urine. Long-term data on the effectiveness of this procedure aren’t available.

Embolization

In this experimental procedure, the blood supply to or from the prostate is selectively blocked, causing the prostate to decrease in size. Long-term data on the effectiveness of this procedure aren’t available.

Open or robot-assisted prostatectomy

The surgeon makes an incision in your lower abdomen to reach the prostate and remove tissue. Open prostatectomy is generally done if you have a very large prostate, bladder damage or other complicating factors. The surgery usually requires a short hospital stay and is associated with a higher risk of needing a blood transfusion.

Follow-up care

Your follow-up care will depend on the specific technique used to treat your enlarged prostate.

Your doctor might recommend limiting heavy lifting and excessive exercise for seven days if you have laser ablation, transurethral needle ablation or transurethral microwave therapy. If you have open or robot-assisted prostatectomy, you might need to restrict activity for six weeks.

Whichever procedure you have, your doctor likely will suggest that you drink plenty of fluids afterward.

Home remedies for enlarged prostate

To help control the symptoms of an enlarged prostate, try to:

- Limit beverages in the evening. Don’t drink anything for an hour or two before bedtime to avoid middle-of-the-night trips to the toilet.

- Limit caffeine and alcohol. They can increase urine production, irritate the bladder and worsen symptoms.

- Limit decongestants or antihistamines. These drugs tighten the band of muscles around the urethra that control urine flow, making it harder to urinate.

- Go when you first feel the urge. Waiting too long might overstretch the bladder muscle and cause damage.

- Schedule bathroom visits. Try to urinate at regular times — such as every four to six hours during the day — to “retrain” the bladder. This can be especially useful if you have severe frequency and urgency.

- Follow a healthy diet. Obesity is associated with enlarged prostate.

- Stay active. Inactivity contributes to urine retention. Even a small amount of exercise can help reduce urinary problems caused by an enlarged prostate.

- Urinate — and then urinate again a few moments later. This practice is known as double voiding.

- Keep warm. Colder temperatures can cause urine retention and increase the urgency to urinate.

The Food and Drug Administration hasn’t approved any herbal medications for treatment of an enlarged prostate.

Studies on herbal therapies as a treatment for enlarged prostate have had mixed results. One study found that saw palmetto extract was as effective as finasteride in relieving symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia, although prostate volumes weren’t reduced. But a subsequent placebo-controlled trial found no evidence that saw palmetto is better than a placebo.

Other herbal treatments — including beta-sitosterol extracts, pygeum and rye grass — have been suggested as helpful for reducing enlarged prostate symptoms. But the safety and efficacy of these treatments hasn’t been proved.

If you take any herbal remedies, tell your doctor. Certain herbal products might increase the risk of bleeding or interfere with other medications you’re taking.

Prostate cancer signs and symptoms

Early prostate cancer usually causes no symptoms.

Prostate cancer that’s more advanced may cause signs and symptoms such as:

- Problems urinating (such as pain, difficulty starting or stopping the stream, or dribbling), including a slow or weak urinary stream or the need to urinate more often, especially at night

- Pain with ejaculation

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Trouble getting an erection (erectile dysfunction)

- Pain in the hips, back (spine), chest (ribs), or other areas from cancer that has spread to bones

- Weakness or numbness in the legs or feet, or even loss of bladder or bowel control from cancer pressing on the spinal cord

Most of these problems are more likely to be caused by something other than prostate cancer. For example, trouble urinating is much more often caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a non-cancerous growth of the prostate. Still, it’s important to tell your health care provider if you have any of these symptoms so that the cause can be found and treated, if needed. Some men might need more tests to check for prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer types

Almost all prostate cancers are adenocarcinomas 24. These cancers develop from the gland cells (the cells that make the prostate fluid that is added to the semen).

There are 2 types of adenocarcinoma of the prostate:

- Acinar adenocarcinoma of the prostate: Most people have this type. It develops in the gland cells that line the prostate gland.

- Ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate: Ductal adenocarcinoma starts in the cells that line the tubes (ducts) of the prostate gland. It tends to grow and spread more quickly than acinar adenocarcinoma.

Other types of prostate cancer include:

- Sarcomas

- Small cell carcinomas. Small cell prostate cancer can also be classed as a type of neuroendocrine cancer. They tend to grow more quickly than other types of prostate cancer.

- Neuroendocrine tumors (other than small cell carcinomas)

- Squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate. Squamous cell carcinoma of the prostate develop from flat cells that cover the prostate. They tend to grow and spread more quickly than adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

- Transitional cell carcinomas also called urothelial carcinoma of the prostate. Transitional cell carcinoma of the prostate starts in the cells that line the tube carrying urine to the outside of the body (the urethra). This type of cancer usually starts in the bladder and spreads into the prostate. But rarely it can start in the prostate and may spread into the bladder entrance and nearby tissues. Between 2 and 4 out of 100 prostate cancers (between 2 and 4%) are transitional cell carcinoma.

These other types of prostate cancer are rare. If you have prostate cancer it is almost certain to be an adenocarcinoma 24.

Some prostate cancers can grow and spread quickly, but most grow slowly. In fact, autopsy studies show that many older men (and even some younger men) who died of other causes also had prostate cancer that never affected them during their lives. In many cases neither they nor their doctors even knew they had it.

Possible pre-cancerous conditions of the prostate

Some research suggests that prostate cancer starts out as a pre-cancerous condition, although this is not yet known for sure 24. These conditions are sometimes found when a man has a prostate biopsy (removal of small pieces of the prostate to look for cancer).

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN)

In prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, there are changes in how the prostate gland cells look under a microscope, but the abnormal cells don’t look like they are growing into other parts of the prostate (like cancer cells would) 24. Based on how abnormal the patterns of cells look, they are classified as:

- Low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia: the patterns of prostate cells appear almost normal

- High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia: the patterns of cells look more abnormal

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia begins to appear in the prostates of some men as early as in their 20s.

Many men begin to develop low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia when they are younger but don’t necessarily develop prostate cancer. The possible link between low-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostate cancer is still unclear.

If high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia is found in your prostate biopsy sample, there is about a 20% chance that you also have cancer in another area of your prostate.

Proliferative inflammatory atrophy (PIA)

In proliferative inflammatory atrophy, the prostate cells look smaller than normal and there are signs of inflammation in the area 24. Proliferative inflammatory atrophy is not cancer, but researchers believe that proliferative inflammatory atrophy may sometimes lead to high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, or perhaps to prostate cancer directly.

Prostate cancer causes

Researchers do not know exactly what causes prostate cancer. Doctors know that prostate cancer begins when cells in the prostate develop changes in their DNA. A cell’s DNA contains the instructions that tell a cell what to do. The changes tell the cells to grow and divide more rapidly than normal cells do. The abnormal cells continue living, when other cells would die.

The accumulating abnormal cells form a tumor that can grow to invade nearby tissue. In time, some abnormal cells can break away and spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body.

In the U.S., about 1 out of 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer during his lifetime. Prostate cancer is more likely to develop in older men and in non-Hispanic Black men. About 6 cases in 10 are diagnosed in men who are 65 or older, and it is rare in men under 40. The average age of men at diagnosis is about 66.

Prostate cancer is more common in Black men than in White men. It is less common in Asian men. A man’s risk of developing prostate cancer depends on many factors. These include:

- age

- genetics and family history

- lifestyle factors

- other medical conditions

Inherited gene mutations

Some gene mutations can be passed from generation to generation (inherited) and are found in all cells in the body. Inherited gene changes are thought to play a role in about 10% of prostate cancers. Cancer caused by inherited genes is called hereditary cancer. Several inherited mutated genes have been linked to hereditary prostate cancer, including:

- BRCA1 and BRCA2: These tumor suppressor genes normally help repair mistakes in a cell’s DNA (or cause the cell to die if the mistake can’t be fixed). Inherited mutations in these genes more commonly cause breast and ovarian cancer in women. But changes in these genes (especially BRCA2) also account for a small number of prostate cancers.

- CHEK2, ATM, PALB2, and RAD51D: Mutations in these other DNA repair genes might also be responsible for some hereditary prostate cancers.

- DNA mismatch repair genes such as MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2: These genes normally help fix mistakes (mismatches) in DNA that can be made when a cell is preparing to divide into 2 new cells. Cells must make a new copy of their DNA each time they divide. Men with inherited mutations in one of these genes have a condition known as Lynch syndrome (also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, or HNPCC), and are at increased risk of colorectal, prostate, and some other cancers.

- RNASEL (formerly HPC1): The normal function of this tumor suppressor gene is to help cells die when something goes wrong inside them. Inherited mutations in this gene might let abnormal cells live longer than they should, which can lead to an increased risk of prostate cancer.

- HOXB13: This gene is important in the development of the prostate gland. Mutations in this gene have been linked to early-onset prostate cancer (prostate cancer diagnosed at a young age) that runs in some families. Fortunately, this mutation is rare.

Other inherited gene mutations may account for some hereditary prostate cancers, and research is being done to find these genes.

Acquired gene mutations

Some genes mutate during a person’s lifetime, and the mutation is not passed on to children. These changes are found only in cells that come from the original mutated cell. These are called acquired mutations. Most gene mutations related to prostate cancer seem to develop during a man’s life rather than having been inherited.

Every time a cell prepares to divide into 2 new cells, it must copy its DNA. This process isn’t perfect, and sometimes errors occur, leaving defective DNA in the new cell. It’s not clear how often these DNA changes might be random events, and how often they are influenced by other factors (such as diet, hormone levels, etc.). In general, the more quickly prostate cells grow and divide, the more chances there are for mutations to occur. Therefore, anything that speeds up this process may make prostate cancer more likely.

For example, androgens (male hormones), such as testosterone, promote prostate cell growth. Having higher levels of androgens might contribute to prostate cancer risk in some men.

Some research has found that men with high levels of another hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), are more likely to get prostate cancer. However, other studies have not found such a link. Further research is needed to make sense of these findings.

Prostate Cancer Risk Factors

A risk factor is anything that affects your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. But having a risk factor, or even several, does not mean that you will get the disease. Many people with one or more risk factors never get cancer, while others who get cancer may have had few or no known risk factors.

Researchers have found several factors that might affect a man’s risk of getting prostate cancer.

- Age. Prostate cancer is rare in men younger than 40, but the chance of having prostate cancer rises rapidly after age 50. About 6 in 10 prostate cancers are found in men older than 65.

- Race/ethnicity. Prostate cancer occurs more often in African-American men and Caribbean men of African ancestry than in men of other races. African-American men are also more than twice as likely to die of prostate cancer than white men. Prostate cancer occurs less often in Asian-American and Hispanic/Latino men than in non-Hispanic whites. The reasons for these racial and ethnic differences are not clear.

- Geography. Prostate cancer is most common in North America, northwestern Europe, Australia, and on Caribbean islands. It is less common in Asia, Africa, Central America, and South America. The reasons for this are not clear. More intensive screening in some developed countries probably accounts for at least part of this difference, but other factors such as lifestyle differences (diet, etc.) are likely to be important as well. For example, Asian Americans have a lower risk of prostate cancer than white Americans, but their risk is higher than that of men of similar backgrounds living in Asia.

- Family history. Prostate cancer seems to run in some families, which suggests that in some cases there may be an inherited or genetic factor. Still, most prostate cancers occur in men without a family history of it. Having a father or brother with prostate cancer more than doubles a man’s risk of developing this disease. The risk is higher for men who have a brother with the disease than for those who have a father with it. The risk is much higher for men with several affected relatives, particularly if their relatives were young when the cancer was found.

- Gene changes. Several inherited gene changes (mutations) seem to raise prostate cancer risk, but they probably account for only a small percentage of cases overall. For example:

- Inherited mutations of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes raise the risk of breast and ovarian cancers in some families. Mutations in these genes (especially in BRCA2) may also increase prostate cancer risk in some men.

- Men with Lynch syndrome also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), a condition caused by inherited gene changes, have an increased risk for a number of cancers, including prostate cancer.

- Other inherited gene changes can also raise a man’s risk of prostate cancer.

Factors with less clear effect on prostate cancer risk

- Diet. The exact role of diet in prostate cancer is not clear, but several factors have been studied. Men who eat a lot of red meat or high-fat dairy products appear to have a slightly higher chance of getting prostate cancer. These men also tend to eat fewer fruits and vegetables. Doctors aren’t sure which of these factors is responsible for raising the risk. Some studies have suggested that men who consume a lot of calcium (through food or supplements) may have a higher risk of developing prostate cancer. Dairy foods (which are often high in calcium) might also increase risk. But most studies have not found such a link with the levels of calcium found in the average diet, and it’s important to note that calcium has other important health benefits.

- Obesity. Being obese (very overweight) does not seem to increase the overall risk of getting prostate cancer. Some studies have found that obese men have a lower risk of getting a low-grade (slower growing) form of the disease, but a higher risk of getting more aggressive (faster growing) prostate cancer. The reasons for this are not clear. Some studies have also found that obese men may be at greater risk for having more advanced prostate cancer and of dying from prostate cancer, but not all studies have found this.

- Smoking. Most studies have not found a link between smoking and getting prostate cancer. Some research has linked smoking to a possible small increased risk of dying from prostate cancer, but this finding needs to be confirmed by other studies.

- Chemical exposures. There is some evidence that firefighters can be exposed to chemicals that may increase their risk of prostate cancer. A few studies have suggested a possible link between exposure to Agent Orange, a chemical used widely during the Vietnam War, and prostate cancer, although not all studies have found such a link. The Institute of Medicine considers there to be “limited/suggestive evidence” of a link between Agent Orange exposure and prostate cancer.

- Inflammation of the prostate. Some studies have suggested that prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate gland) may be linked to an increased risk of prostate cancer, but other studies have not found such a link. Inflammation is often seen in samples of prostate tissue that also contain cancer. The link between the two is not yet clear, and is an active area of research.

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Researchers have looked to see if sexually transmitted infections (like gonorrhea or chlamydia) might increase the risk of prostate cancer, because they can lead to inflammation of the prostate. So far, studies have not agreed, and no firm conclusions have been reached.

- Vasectomy. Some studies have suggested that men who have a vasectomy (minor surgery to make men infertile) have a slightly increased risk for prostate cancer, but other studies have not found this. Research on this possible link is still being done.

Prostate cancer prevention

There is no sure way to prevent prostate cancer. Many risk factors such as age, race, and family history can’t be controlled. But there are some things you can do that might lower your risk for this disease.

Body weight, physical activity, and diet

The effects of body weight, physical activity, and diet on prostate cancer risk are not clear, but there are things you can do that might lower your risk.

Some studies have found that men who are overweight may have a slightly lower risk of prostate cancer overall, but a higher risk of prostate cancers that are likely to be fatal.

Studies have found that men who are regularly physically active have a slightly lower risk of prostate cancer. Vigorous activity may have a greater effect, especially on the risk of advanced prostate cancer.

Several studies have suggested that diets high in certain vegetables (including tomatoes, cruciferous vegetables, soy, beans, and other legumes) or fish may be linked with a lower risk of prostate cancer, especially more advanced cancers. Examples of cruciferous vegetables include cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower.

Although not all studies agree, several have found a higher risk of prostate cancer in men whose diets are high in calcium. There may also be an increased risk from consuming dairy foods.

For now, the best advice about diet and activity to possibly reduce the risk of prostate cancer is to:

- Follow a healthy eating pattern, which includes a variety of colorful fruits and vegetables and whole grains, and avoids or limits red and processed meats, sugar-sweetened beverages, and highly processed foods.

- Be physically active.

- Stay at a healthy weight.

It may also be sensible to limit calcium supplements and to not get too much calcium in the diet. This does not mean that men who are being treated for prostate cancer should not take calcium supplements if their doctor recommends them.

Vitamin, mineral, and other supplements

- Vitamin E and selenium: Some earlier studies suggested that taking vitamin E or selenium supplements might lower prostate cancer risk. But in a large study known as the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT), neither vitamin E nor selenium supplements were found to lower prostate cancer risk. In fact, men in the study taking the vitamin E supplements were later found to have a slightly higher risk of prostate cancer.

- Soy and isoflavones: Some early research has suggested possible benefits from soy proteins called isoflavones in lowering prostate cancer risk. Several studies are now looking more closely at the possible effects of these proteins.

Taking any supplements can have both risks and benefits. Before starting vitamins or other supplements, talk with your doctor.

Medicines

Some drugs might help reduce the risk of prostate cancer.

- 5-alpha reductase inhibitors. 5-alpha reductase is an enzyme in the body that changes testosterone into dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the main hormone that causes the prostate to grow. Drugs called 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, such as finasteride (Proscar) and dutasteride (Avodart), block this enzyme from making DHT. These drugs are used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a non-cancerous growth of the prostate. Large studies of both of these drugs have been done to see if they might also be useful in lowering prostate cancer risk. In these studies, men taking either drug were less likely to develop prostate cancer after several years than men getting an inactive placebo. When the results were looked at more closely, the men who took these drugs had fewer low-grade prostate cancers, but they had about the same (or a slightly higher) risk of higher-grade prostate cancers, which are more likely to grow and spread. Long term, it’s not clear if these drugs affect death rates, as men in these studies had similar survival whether or not they took one of these drugs. These drugs can cause sexual side effects such as lowered sexual desire and erectile dysfunction (impotence), as well as the growth of breast tissue in some men. But they can help with urinary problems from BPH such as trouble urinating and leaking urine (incontinence). These drugs aren’t approved by the FDA specifically to help prevent prostate cancer, although doctors can prescribe them “off label” for this use. Right now, it isn’t clear that taking one of these drugs just to lower prostate cancer risk is very helpful. Still, men who want to know more about these drugs should discuss them with their doctors.

- Aspirin. Some research suggests that men who take a daily aspirin might have a lower risk of getting and dying from prostate cancer. But more research is needed to show if the possible benefits outweigh the risks. Long-term aspirin use can have side effects, including an increased risk of bleeding in the digestive tract. While aspirin can also have other health benefits, at this time most doctors don’t recommend taking it just to try to lower prostate cancer risk.

- Other drugs. Other drugs and dietary supplements that might help lower prostate cancer risk are now being studied. But so far, no drug or supplement has been found to be helpful in studies large enough for experts to recommend them.

Prostate cancer screening

Screening is testing to find cancer in people before they have symptoms. For some types of cancer, screening can help find cancers at an early stage, when they are likely to be easier to treat. However, testing healthy men with no symptoms for prostate cancer is controversial. There is some disagreement among medical organizations whether the benefits of testing outweigh the potential risks. Most medical organizations encourage men in their 50s to discuss the pros and cons of prostate cancer screening with their doctors. The discussion should include a review of your risk factors and your preferences about screening. You might consider starting the discussions sooner if you’re a Black person, have a family history of prostate cancer or have other risk factors.

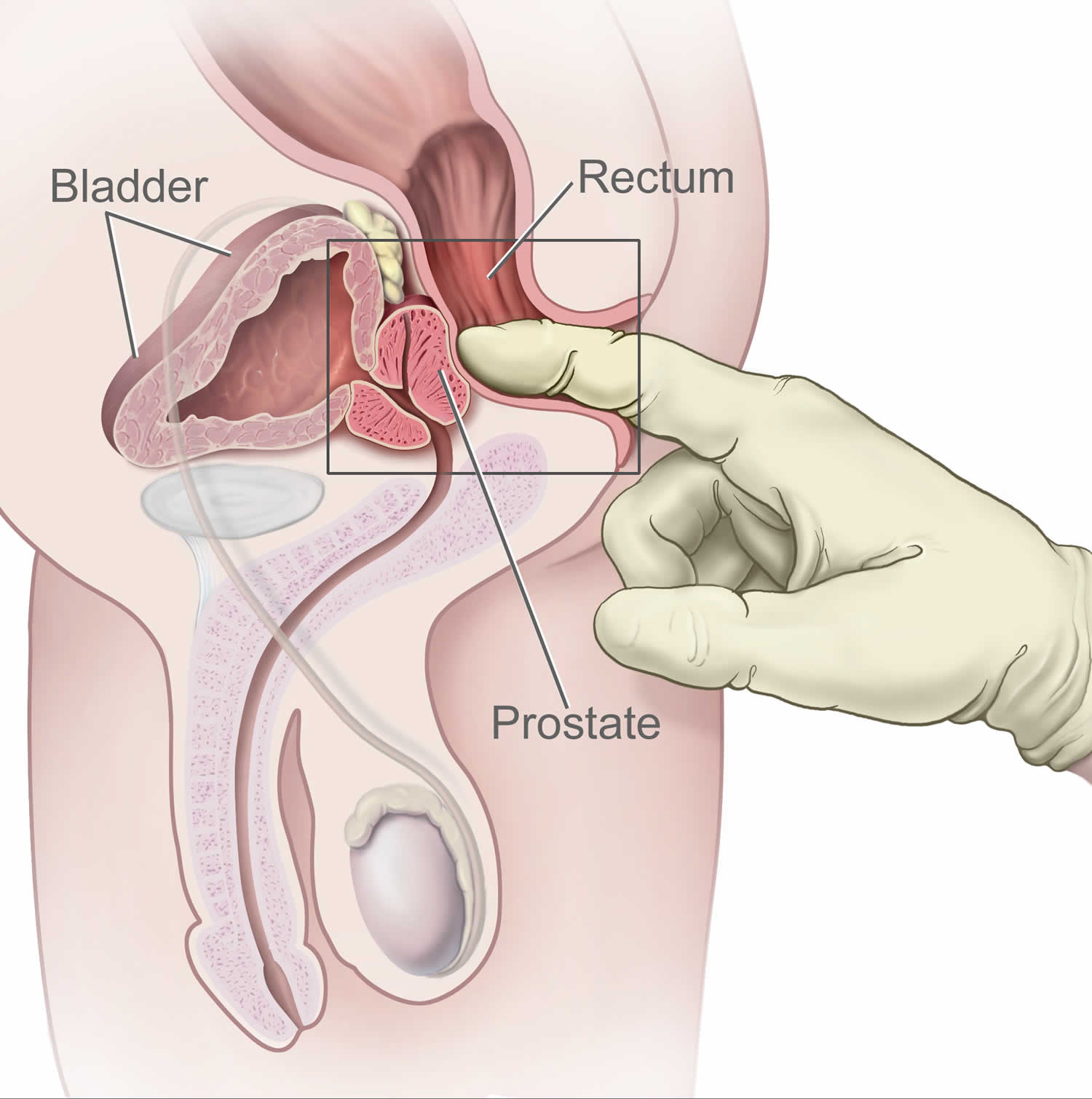

Prostate cancer can often be found before symptoms start by testing the amount of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in a man’s blood. Another way to find prostate cancer is the digital rectal exam (DRE), in which the doctor puts a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum to feel the prostate gland.

Prostate screening tests might include:

- Digital rectal exam (DRE). During a digital rectal exam (DRE), your doctor inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into your rectum to examine your prostate, which is adjacent to the rectum. This exam can be uncomfortable (especially for men who have hemorrhoids), but it usually isn’t painful and only takes a short time. If your doctor finds any abnormalities in the texture, shape or size of the gland, you may need further tests.

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a protein made by cells in the prostate gland (both normal cells and cancer cells). PSA is mostly found in semen, but a small amount is also found in blood. The PSA level in blood is measured in units called nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL). The chance of having prostate cancer goes up as the PSA level goes up, but there is no set cutoff point for PSA level that can tell for sure if a man does or doesn’t have prostate cancer. Many doctors use a PSA cutoff point of 4 ng/mL or higher when deciding if a man might need further testing, while others might recommend it starting at a lower level, such as 2.5 or 3 ng/mL.

- Most men without prostate cancer have PSA levels under 4 ng/mL of blood. When prostate cancer develops, the PSA level often goes above 4 ng/mL. Still, a level below 4 ng/mL is not a guarantee that a man doesn’t have cancer. About 15% of men with a PSA below 4 ng/mL will have prostate cancer if a biopsy is done.

- Men with a PSA level between 4 and 10 ng/mL (often called the “borderline range”) have about a 1 in 4 chance of having prostate cancer.

- If the PSA is more than 10, the chance of having prostate cancer is over 50%.

- If your PSA level is high, you might need further tests to look for prostate cancer (e.g., prostate biopsy). For some men, getting a prostate biopsy might be the best option, especially if the initial PSA level is high. A biopsy is a procedure in which small samples of the prostate are removed and then looked at under a microscope. This test is the only way to know for sure if a man has prostate cancer. If prostate cancer is found on a biopsy, this test can also help tell how likely it is that the cancer will grow and spread quickly.

One reason it’s hard to use a set cutoff point with the PSA test when looking for prostate cancer is that a number of factors other than cancer can also affect PSA levels.

Factors that might raise PSA levels include:

- An enlarged prostate: Conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate that affects many men as they grow older, can raise PSA levels.

- Older age: PSA levels normally go up slowly as you get older, even if you have no prostate abnormality.

- Prostatitis: This is an infection or inflammation of the prostate gland, which can raise PSA levels.

- Ejaculation: This can make the PSA go up for a short time. This is why some doctors suggest that men abstain from ejaculation for a day or two before testing.

- Riding a bicycle: Some studies have suggested that cycling may raise PSA levels for a short time (possibly because the seat puts pressure on the prostate), although not all studies have found this.

- Certain urologic procedures: Some procedures done in a doctor’s office that affect the prostate, such as a prostate biopsy or cystoscopy, can raise PSA levels for a short time. Some studies have suggested that a digital rectal exam (DRE) might raise PSA levels slightly, although other studies have not found this. Still, if both a PSA test and a DRE are being done during a doctor visit, some doctors advise having the blood drawn for the PSA before having the DRE, just in case.

- Certain medicines: Taking male hormones like testosterone (or other medicines that raise testosterone levels) may cause a rise in PSA.

Some things might lower PSA levels (even if a man has prostate cancer):

- 5-alpha reductase inhibitors: Certain drugs used to treat BPH or urinary symptoms, such as finasteride (Proscar or Propecia) or dutasteride (Avodart), can lower PSA levels. These drugs can also affect prostate cancer risk (discussed in Can Prostate Cancer Be Prevented?). Tell your doctor if you are taking one of these medicines. Because they can lower PSA levels, the doctor might need to adjust for this.

- Herbal mixtures: Some mixtures that are sold as dietary supplements might mask a high PSA level. This is why it’s important to let your doctor know if you are taking any type of supplement, even ones that are not necessarily meant for prostate health. Saw palmetto (an herb used by some men to treat BPH) does not seem to affect PSA.

- Certain other medicines: Some research has suggested that long-term use of certain medicines, such as aspirin, statins (cholesterol-lowering drugs), and thiazide diuretics (such as hydrochlorothiazide) might lower PSA levels. More research is needed to confirm these findings. If you take any of the medicines regularly, talk to your doctor before you stop taking it for any reason.

For men who might be screened for prostate cancer, it’s not always clear if lowering the PSA is helpful. In some cases the factor that lowers the PSA may also lower a man’s risk of prostate cancer. But in other cases, it might lower the PSA level without affecting a man’s risk of cancer. This could actually be harmful, if it were to lower the PSA from an abnormal level to a normal one, as it might result in not detecting a cancer. This is why it’s important to talk to your doctor about anything that might affect your PSA level.

Special types of PSA tests

Some doctors might consider using different types of PSA tests (discussed below) to help decide if you need a prostate biopsy, but not all doctors agree on how to use these other PSA tests. If your PSA test result isn’t normal, ask your doctor to discuss your cancer risk and your need for further tests.

- Percent-free PSA: PSA occurs in 2 major forms in the blood. One form is attached to blood proteins, while the other circulates free (unattached). The percent-free PSA (fPSA) is the ratio of how much PSA circulates free compared to the total PSA level. The percentage of free PSA is lower in men who have prostate cancer than in men who do not. This test is sometimes used to help decide if you should have a prostate biopsy if your PSA results are in the borderline range (like between 4 and 10). A lower percent-free PSA means that your chance of having prostate cancer is higher and you should probably have a biopsy. Many doctors recommend biopsies for men whose percent-free PSA is 10% or less, and advise that men consider a biopsy if it is between 10% and 25%. Using these cutoffs detects most cancers and helps some men avoid unnecessary prostate biopsies. This test is widely used, but not all doctors agree that 25% is the best cutoff point to decide on a biopsy, and the cutoff may change depending on the overall PSA level.

- Complexed PSA: This test directly measures the amount of PSA that is attached to other proteins (the portion of PSA that is not “free”). This test could be done instead of checking the total and free PSA, and it could give the same amount of information as the other tests done separately. This test is being studied to see if it provides the same level of accuracy. Tests that combine different types of PSA: Some newer tests, such as the prostate health index (phi) and the 4Kscore test, combine the results of different types of PSA to get an overall score that reflects the chance a man has prostate cancer. These tests might be useful in men with a slightly elevated PSA, to help determine if they should have a prostate biopsy. Some tests might be used to help determine if a man who has already had a prostate biopsy that didn’t find cancer should have another biopsy.

- The Prostate Health Index (PHI), which combines the results of total PSA, free PSA, and proPSA

- The 4Kscore test, which combines the results of total PSA, free PSA, intact PSA, and human kallikrein 2 (hK2), along with some other factors

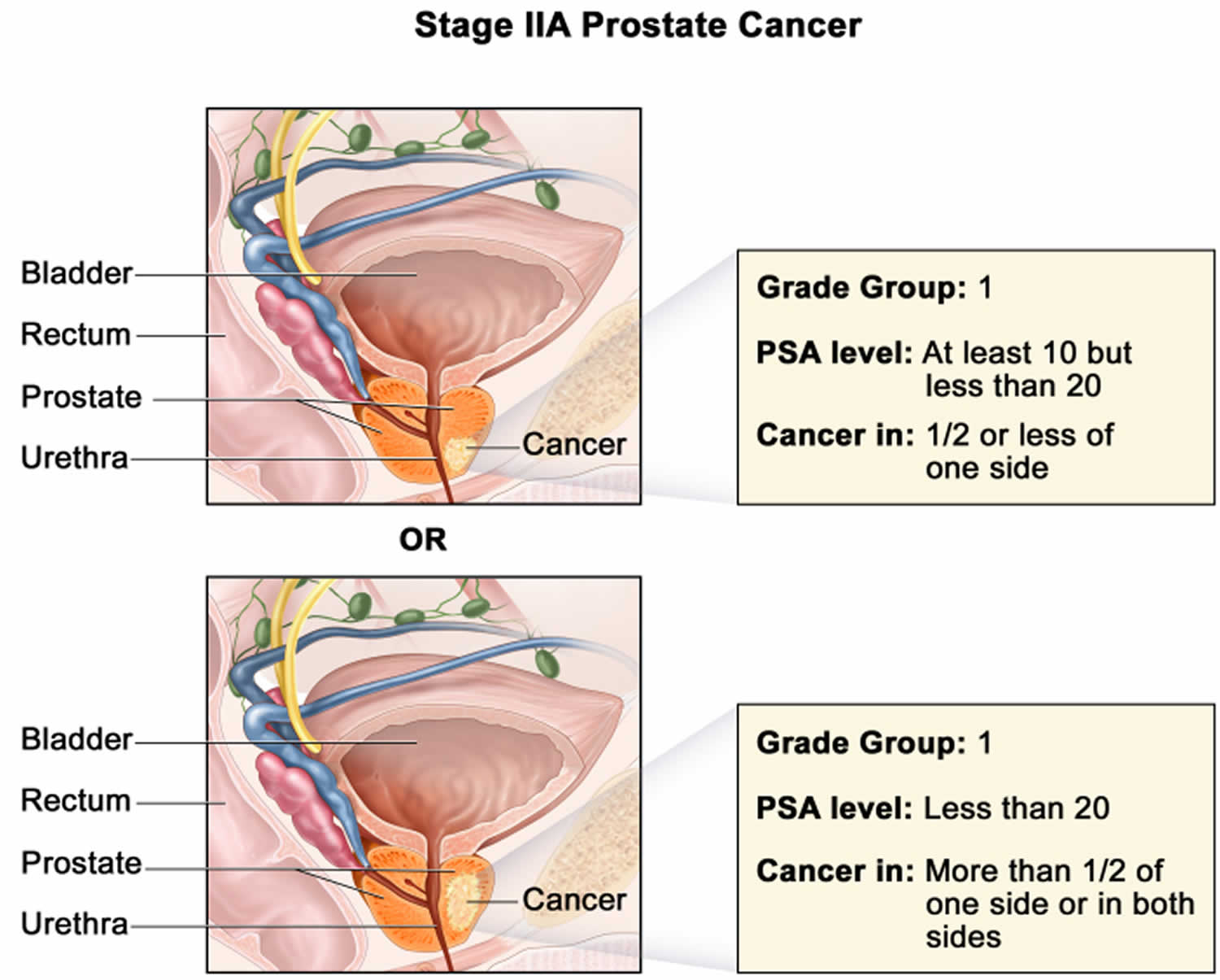

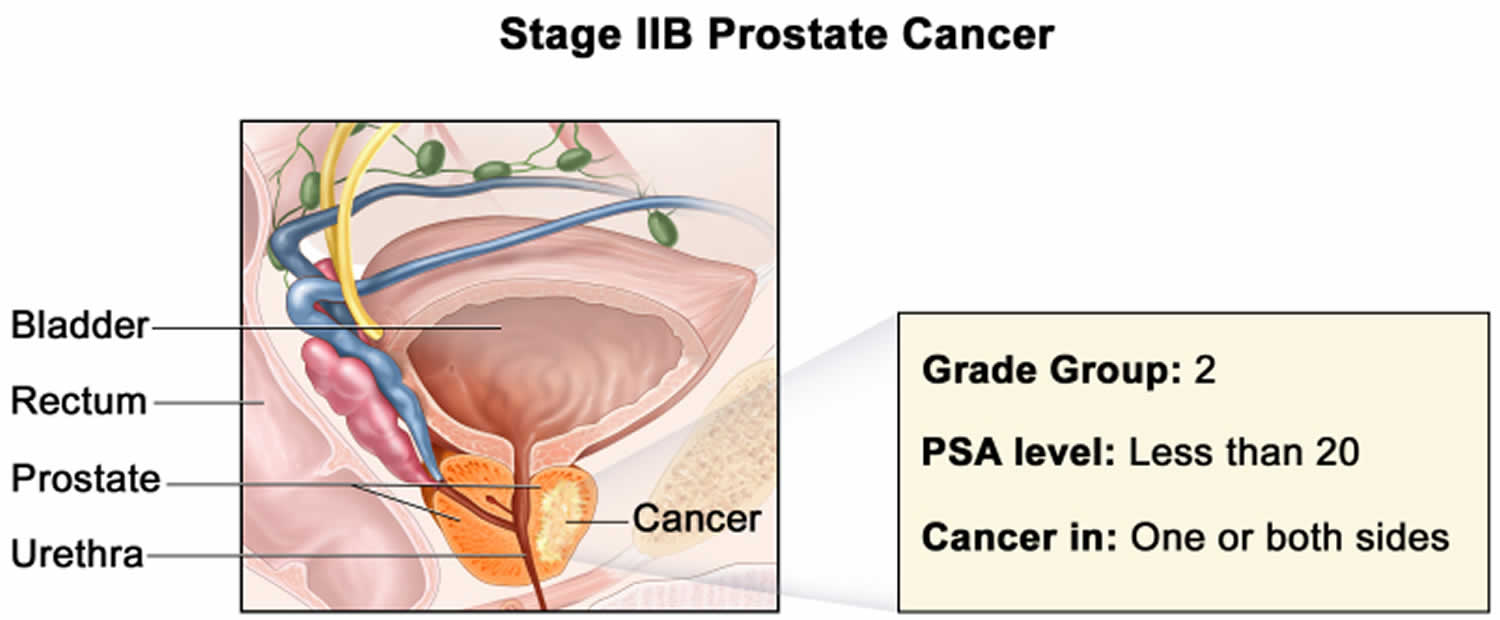

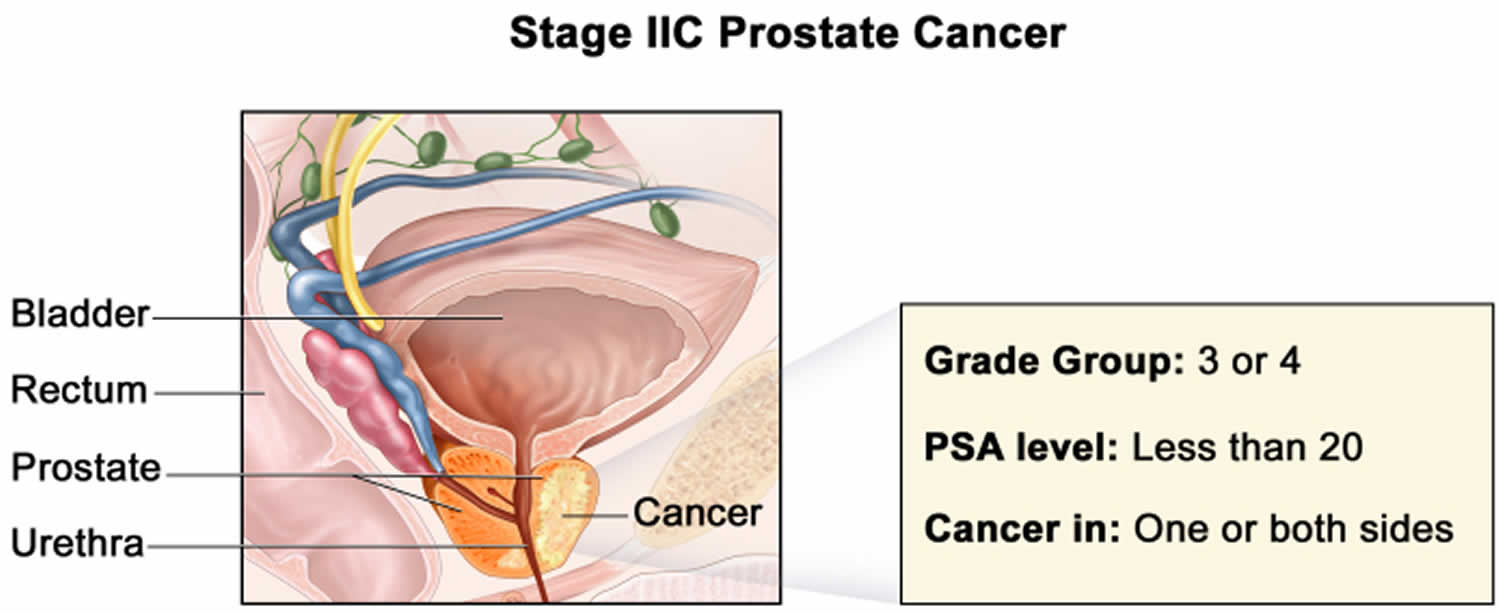

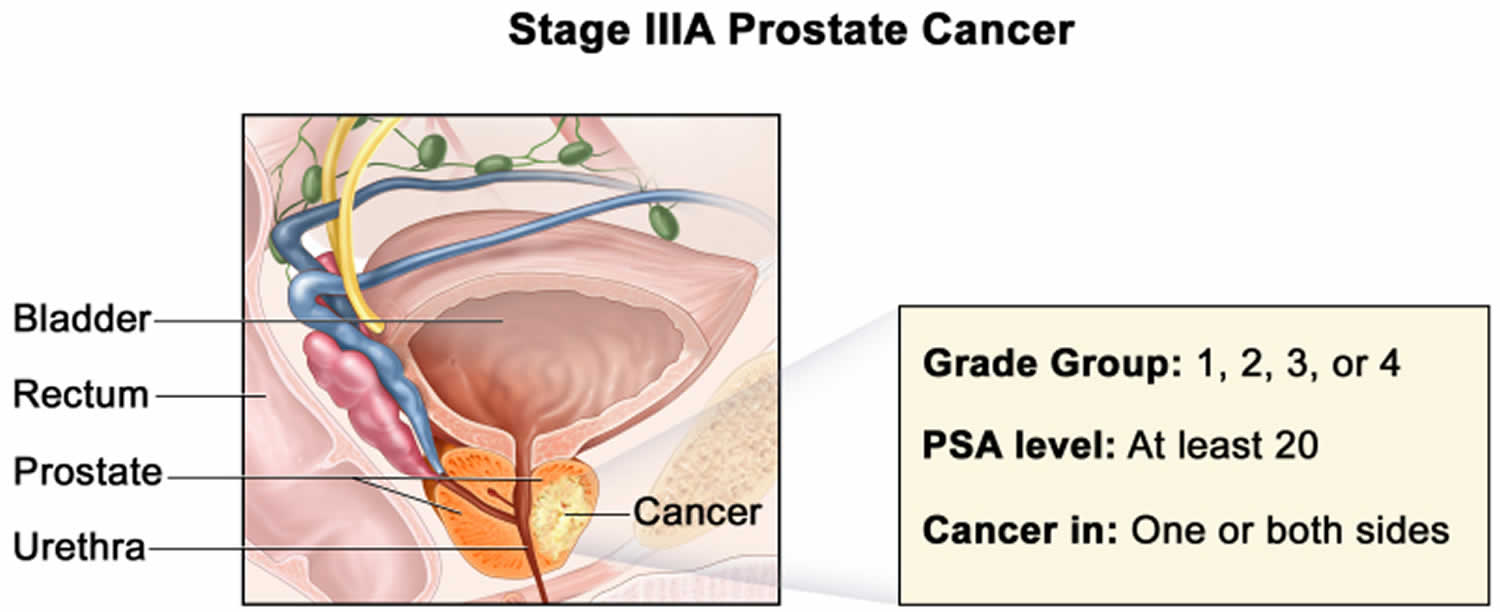

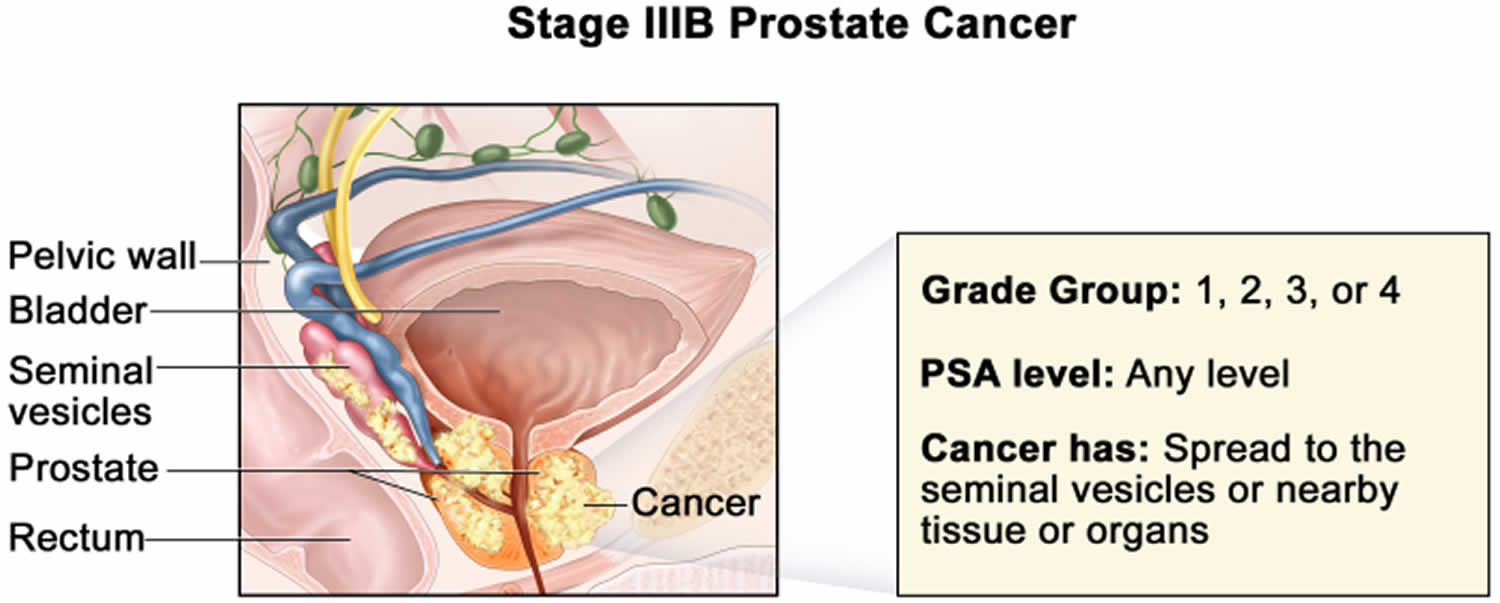

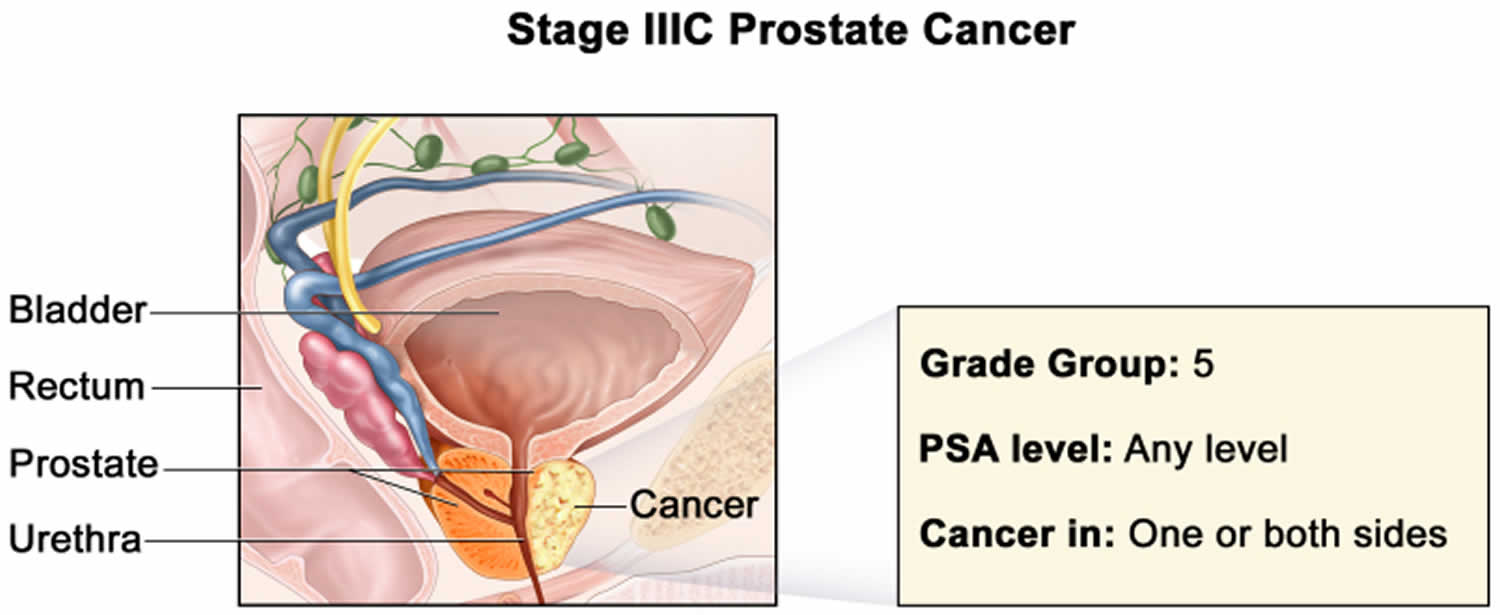

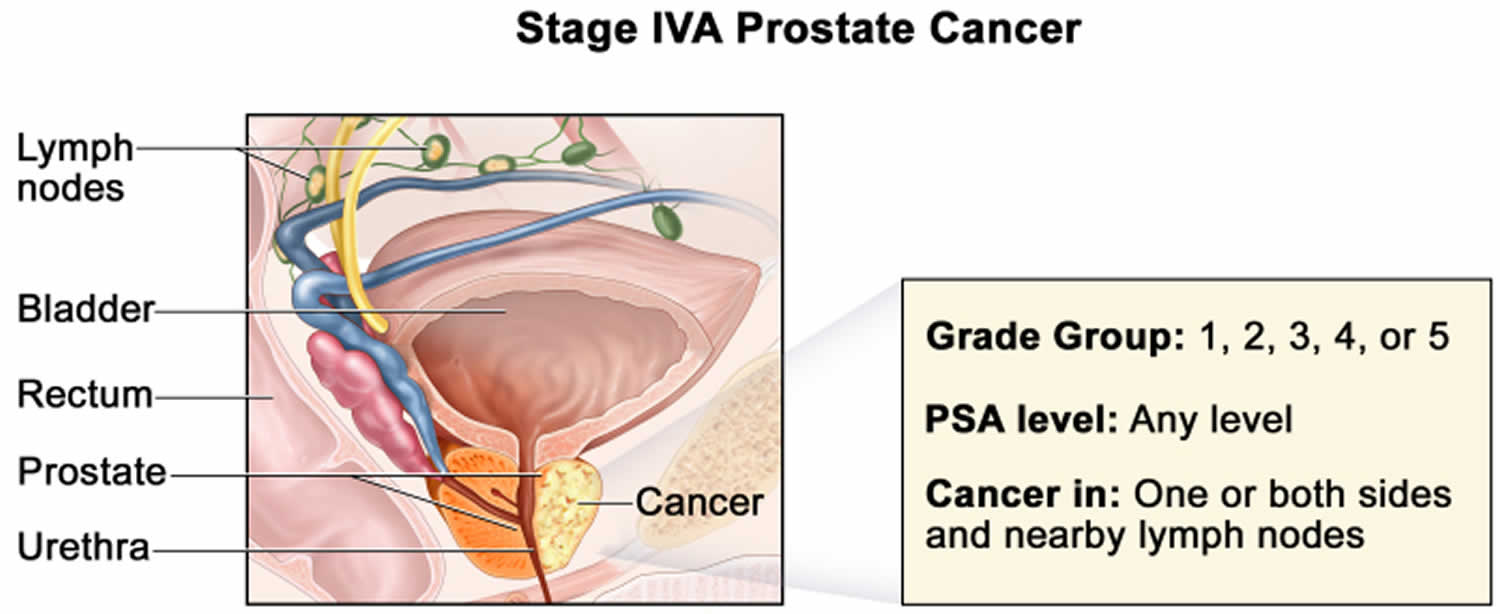

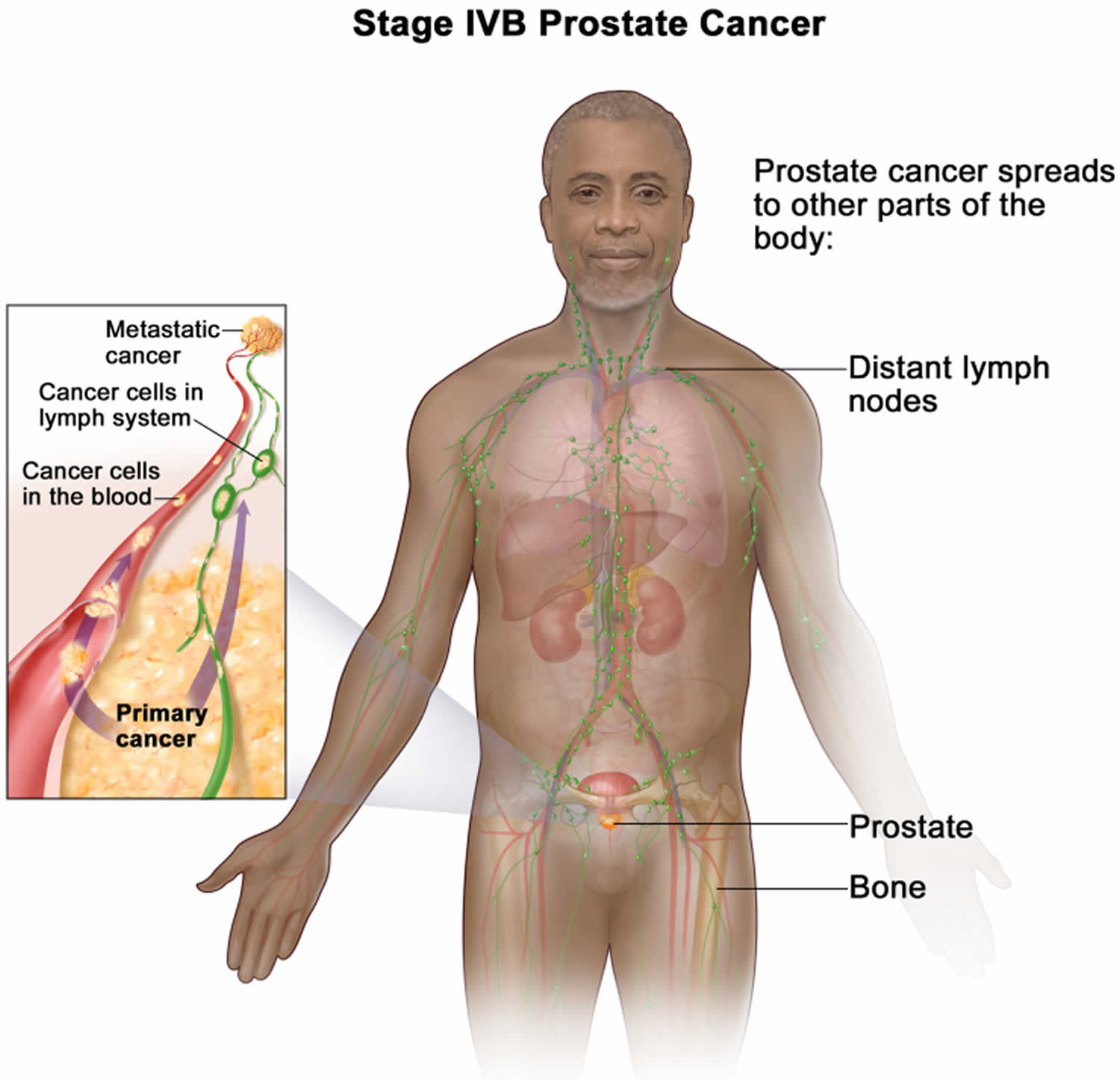

- PSA velocity: The PSA velocity is not a separate test. It is a measure of how fast the PSA rises over time. Normally, PSA levels go up slowly with age. Some research has found that these levels go up faster if a man has cancer, but studies have not shown that the PSA velocity is more helpful than the PSA level itself in finding prostate cancer. For this reason, the American Cancer Society guidelines do not recommend using the PSA velocity as part of screening for prostate cancer.