Pseudopolyps

Pseudopolyps also called inflammatory polyps, post-inflammatory polyps or inflammatory pseudopolyps, formed as a consequence of alternating cycles of inflammation and regeneration of the ulcerated epithelium 1. Pseudopolyps form as islands of regenerating mucosa and granulation tissue surrounded by sections of ulceration bulge into the intestinal lumen 2. Inflammatory pseudopolyps also contain a submucosal core as the tissue heals. The term pseudopolyps, however, has been applied to the characterization of surviving islets of mucosa between ulcers during a severe attack, which create the impression of a polyp 3 and of loose mucosal tags, which are formed because of severe ulceration undermining the integrity of the muscularis mucosa. In conjunction with the inflammation process and cellular infiltration of the submucosa, granulation tissue is formed, which is more intense in some focal areas, thereby producing inflammatory pseudopolyps 4. During the healing process, which features re-epithelization and excessive regeneration, post-inflammatory pseudopolyps are formed 5, taking their shape from the elongation of mucosal tags related to the bowel’s peristaltic contractions and the stream of feces 6. From this perspective, the post-inflammatory polyps can be separated into the following categories: (1) pseudopolyps; (2) inflammatory polyps; and (3) post-inflammatory polyps 7.

Pseudopolyps are thought to develop as a result of repeated alternating cycles of inflammation and healing of the intestinal mucosa in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions 8. Pseudopolyps are usually confined to the colon. Inflammatory pseudopolyps are encountered in 20%–45% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colonic involvement 9. There is a subgroup of patients with ulcerative colitis (10-20%) who present on endoscopy with pseudopolyps, typically formed at the bowel wall during repetitive inflammation attacks 10. Pseudopolyps have been associated with an increased burden of disease in the context of intermediate risk of colorectal cancer and the need for increased surveillance 11. However, another study showed there is no convincing evidence that inflammatory pseudopolyps undergo dysplastic or neoplastic changes 12. And according to new findings 13, pseudopolyp were shown to not be associated with colorectal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Furthermore, patients with inflammatory pseudopolyps had more severe histologic inflammation, more often had extensive colitis, and were significantly more likely to undergo colectomy 13. The new findings suggest that inflammatory pseudopolyps are related to the inflammatory burden, but are not themselves a dominant risk factor for colorectal neoplasia 13.

Pseudopolyps generally are seen in patients with more severe and widely distributed inflammation 14. Inflammatory polyposis can develop in patients within a short period of time after the onset of clinically recognized inflammation, and pseudopolyps may be seen during the first acute attack of inflammatory bowel disease 14. Pseudopolyps are seen in patients with active or quiescent inflammatory bowel disease 15. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease complicated by dilation and megacolon are also more likely to have inflammatory polyposis 14. Besides the well‐recognized symptoms and complications that are usually associated with inflammatory bowel disease, the presence of inflammatory polyposis may be associated with unique complications. Colonic obstruction has been caused by inflammatory polyposis in patients with ulcerative colitis, even in the absence of acute inflammation 16. Protein‐losing enteropathy has also occurred in this setting 17. Filiform polyposis is the term used to describe the presence of slender, finger‐like projections protruding into the lumen of the colon from the mucosal surface, most often in patients with inflammatory bowel disease 18. The projections are composed of cores of normal submucosa surrounded by minimally inflamed mucosa. Such lesions were first described in middle‐aged patients years after an episode of acute colitis 19. Filiform polyposis has been described in patients with both forms of idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease 18. These lesions may cause obstruction, hemorrhage or may be asymptomatic in patients with otherwise quiescent inflammatory bowel disease 18. In addition to being found in the colon, filiform polyposis has also been seen in the stomach in a patient with Crohn’s disease involving the small bowel 20.

Inflammatory polyposis has also been reported in association with other conditions besides inflammatory bowel disease, including ischemic colitis 21. Infectious colitis may sometimes result in inflammatory polyposis. Twelve of 25 patients with tuberculous colitis were shown to have inflammatory polyposis in one series 22. A Caucasian man developed amoebic colitis associated with extensive pseudopolyps after traveling to India 23. Polyposis has also been reported in Egyptian patients with schistosomal disease of the colon 24 and in one man from the Aegean island of Mytilinae who had colitis due to infestation with Balantidium coli, a parasite that commonly infects pigs 25. Another interesting case report describes inflammatory polyposis in a Korean patient diagnosed with Behçet’s disease 26. Finally, multiple pseudopolyps were seen in an ileal blind loop in a patient who had undergone partial gastrectomy and Billroth II gastrojejunostomy for peptic ulcer disease 11 years before presenting with symptoms of chronic diarrhea. This patient had no history of other findings consistent with inflammatory bowel disease 27.

A condition known as cap polyposis may be a variant of inflammatory polyposis. First described in 1985, this condition is not associated with inflammatory bowel disease but rather tends to occur in patients with mucosal prolapse 28. The lesions consist of elongated, tortuous and occasionally distended crypts covered with a `cap’ of inflammatory granulation tissue. They are usually distributed from the rectum to the distal descending colon 28. Patients typically present with diarrhea, tenesmus, hematochezia 29 and protein‐losing enteropathy 28. In at least one patient, avoidance of straining during defecation resulted in symptomatic and endoscopic improvement, but in some patients surgery has been required 28.

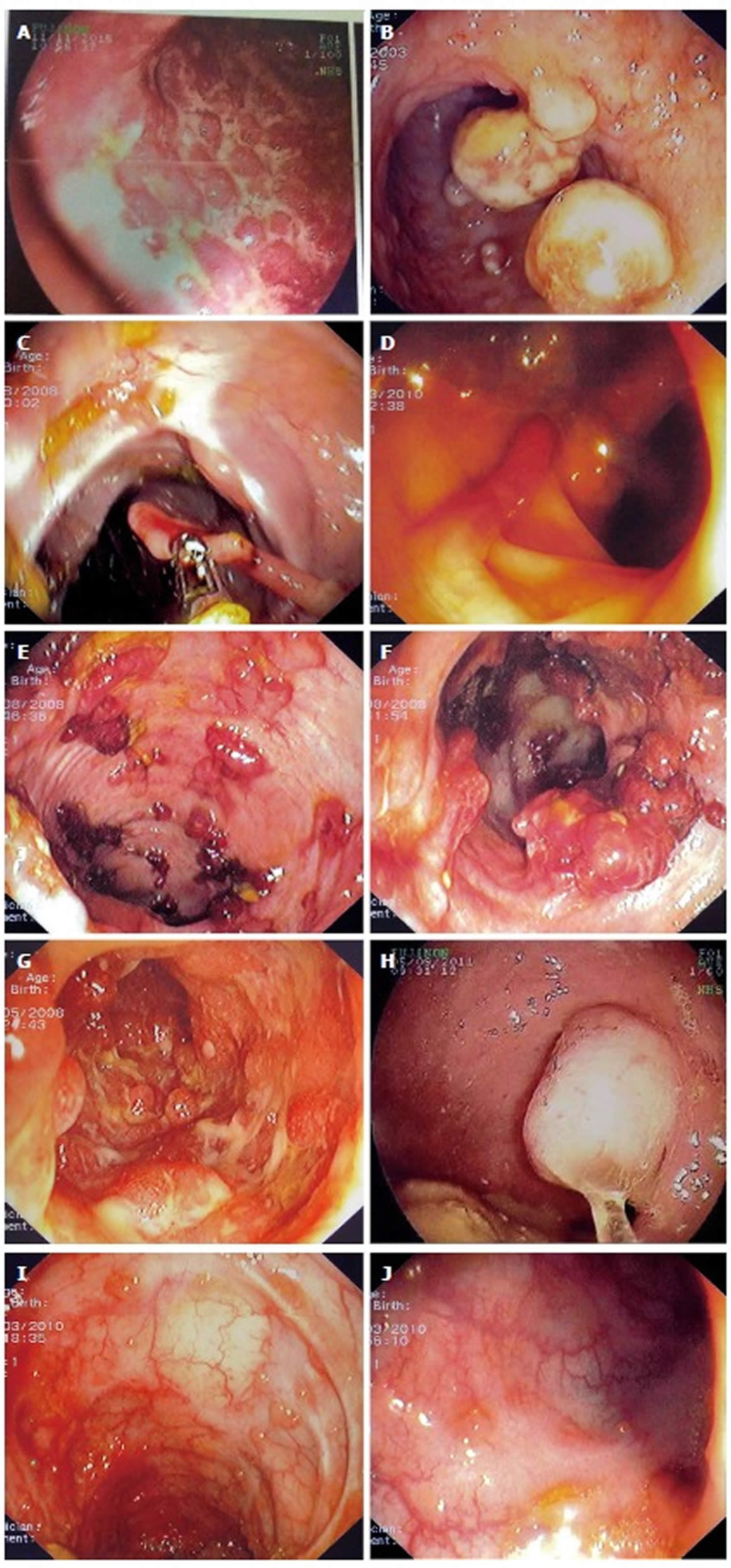

Figure 1. Pseudopolyps

Footnote: Examples of various types of pseudopolyps in different patients with inflammatory bowel disease. (A) Endoscopic picture of deep ulcers and residual islets of surviving mucosa, the “true” pseudopolyps; (B) Localized pseudopolyps of varying size up to 1.6 cm with discrete borders, pale surface, exudates on surface and varying forms. Biopsy of the polyps revealed inflammatory infiltration of lymphocytes, distortion and branching of the crypts compatible with post inflammatory pseudopolyps; (C) Long filiform pseudopolyp located in the transverse colon captured with biopsy forceps; (D) Localized filiform pseudopolyposis located in sigmoid colon; (E) Post-inflammatory generalized pseudopolyposis; (F) Cluster of pseudopolyps in sigmoid colon with 2.5 cm size, creating a giant localized pseudopolyp. Multiple biopsies of the polyp showed lined epithelium with a core of connective tissue and vessels with inflammatory infiltration which confirmed the diagnosis of pseudopolyp; (G) Multiple pseudopolyps stubble the sigmoid colon. In this case, surveillance for dysplasia-associated lesion or mass can be challenging because of the intense inflammation and the multiple pseudopolyps; (H) Pseudopolyp or adenoma-like mass? Solitary polyp with 1.5 cm size and broad-based with discrete borders but without exudates, amenable to endoscopic removal and having a pale surface. Histology after removal of the polyp with electrocautery showed villous adenoma with mild dysplasia, and without dysplasia in the surrounding mucosa or elsewhere in the colon, compatible with adenoma-like mass; (I) Localized post-inflammatory pseudopolyps; (J) Localized pseudopolyps of 0.3 cm maximum size, located in sigmoid colon with discrete borders and pale, glistering surface. Endoscopic characteristics were adequate for recognition of pseudopolyps without the need for biopsies or further intervention.

[Source 7 ]Pseudopolyps key facts

- Pseudopolyps are markers of episodes of severe inflammation, encountered in endoscopy in a subgroup of patients with ulcerative colitis.

- Their clinical significance is uncertain, except for their link with an intermediate risk for colorectal cancer

- Pseudopolyps are not included in endoscopic scores for monitoring the activity of ulcerative colitis

- The presence of pseudopolyps in patients with ulcerative colitis was associated with rapid escalation of treatment, escalation to biological agents or surgery, and possibly with bowel stenosis

- The presence of pseudopolyps in ulcerative colitis patients was not associated with a greater need for hospitalization

- Patients with ulcerative colitis and pseudopolyps may represent a subgroup with a greater burden of disease in terms of increased immunosuppressive treatment.

The presence of inflammatory pseudopolyps in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease can be an indirect marker of previous episodes of severe inflammation, and their incidence rises with more extensive colitis. Although there are not any clear prognostic criteria predicting their formation, it is a common belief that intense flares and hyperplastic healing predispose to inflammatory pseudopolyp formation. A cornerstone study by De Dombal et al 30, involving 465 patients with ulcerative colitis, has shown that 19.5% of patients with total colitis had inflammatory pseudopolyps and 38% of the patients with inflammatory pseudopolyps had suffered at least one episode of severe flare; in addition, 57.1% of the patients who underwent colectomy to address fulminant ulcerative colitis in 1956 had inflammatory pseudopolyp. This high prevalence can be attributable to severe active disease 31. Teague et al 32 expressed a similar opinion, citing a inflammatory pseudopolyp prevalence of 41% in 48 patients with total colitis, and Jalan et al 4 reported that 31% of patients with severe ulcerative colitis had inflammatory pseudopolyp.

In regards to predicting inflammatory pseudopolyp formation, Babic et al 33 proposed that elevation in two of the three following parameters-C-reactive protein, C4 and procollagen III peptide-accompany formation of inflammatory pseudopolyp in ulcerative colitis, calculating the positive predictive value and accuracy to be as high as 90% and 93%, respectively. The existence of inflammatory pseudopolyp has also been linked with the occurrence of extra-intestinal symptoms, specifically arthropathy 4. Their presence in general, however, does not characterize any specific phase of inflammatory bowel disease, as they can be found in both active and quiescent disease states, with the exception of the first form (i.e., the mucosal remnants) which are only found in active inflammatory bowel disease 34.

Pseudopolyps and cancer

Patients with inflammatory pseudopolyp are considered to be at intermediate risk for colorectal cancer. United Kingdom guidelines suggest surveillance colonoscopy be performed at a 3-year interval 35, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization guidelines suggest colonoscopy at 2- or 3-year intervals 36 and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy suggests between 1- and 3-year intervals 37. Three studies, performed by Rutter et al 38, Velayos et al 39 and Baars et al 40, have shown a near 2-fold increased risk of colorectal cancer in patients with previous or present inflammatory pseudopolyp in endoscopy. In much older reports, there was a debate about the possibility of inflammatory pseudopolyp malignant transformation, with advocates representing both sides. Among these, Goldgraber et al 3 reported a case series of several forms of inflammatory pseudopolyp with some showing premalignant changes, but later analysis proved these were benign lesions, regardless of size 4.

Nowadays, malignant transformation of inflammatory pseudopolyp is considered an extremely rare event, with only two reports of giant inflammatory pseudopolyp harboring carcinoma or dysplasia features 5, 41. Another case report from Klarskov et al 42 presented a carcinoma in rectum stump that had arose from serrated adenoma with a filiform form. The authors speculated that the serrated adenoma had derived from transformation of preexisting inflammatory pseudopolyp. A possible mechanism has been implicated by Jawad et al 43, who reported that inflammatory pseudopolyp can be the source of premalignant mutations, following their analysis of DNA taken from 30 inflammatory pseudopolyp samples and which showed four identifiable mutations. However, more studies are needed to confirm the doubt in their benign nature.

A possible explanation about the relationship between inflammatory pseudopolyp and increased risk of colorectal cancer lies in the facts that they are considered markers of episodes of previous severe inflammation and that their incidence of appearance rises with the increased extent of colitis 30, which is in turn linked to colorectal cancer. Another possible explanation is that their presence, especially if they are numerous, can obscure the capability of finding dysplastic lesions in endoscopic surveillance 39.

Pseudopolyps distinct forms

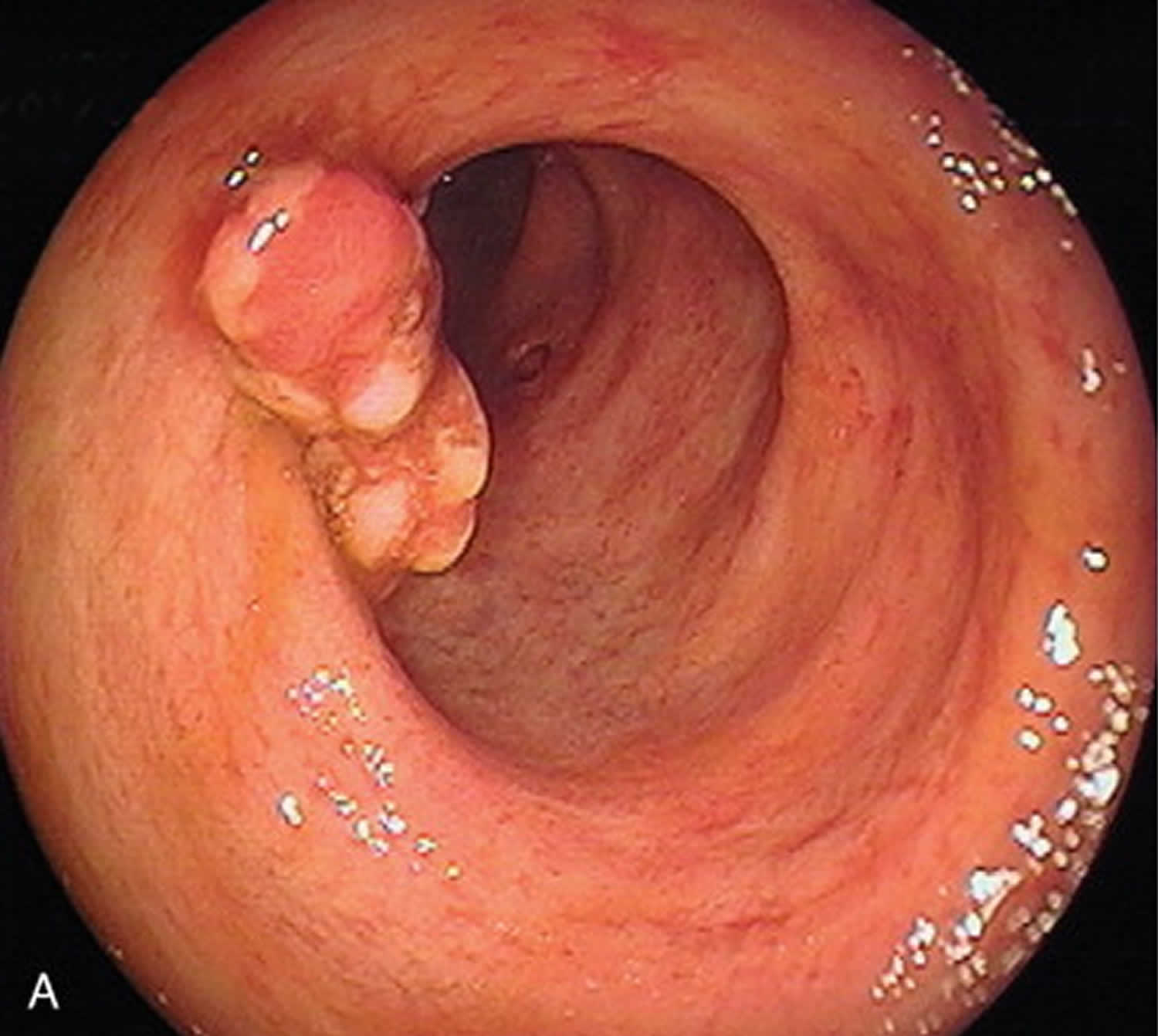

Inflammatory pseudopolyps exist in a variety of forms, including sessile, frond-like and pedunculated, and they can occur as solitary or multiple, or as diffuse or localized in distribution 3. They also vary in size, but are usually short. When a inflammatory pseudopolyp exceeds 1.5 cm in size (Figure 1B), the term giant pseudopolyp has prevailed for their characterization 44, with this description first appearing in the literature in 1965 3.

A distinct form of the post-inflammatory polyps is the filiform polyps. These appear as slender, finger-like or worm-like projections of the mucosa and sub-mucosa, and look like a polyp stalk without a head and often with branching (Figure 1C and 1D) 45. They often create a cluster, and as such are termed as localized giant pseudopolyposis (Figure 1E and 1F) 46. In the literature, the term filiform polyposis often accounts for giant inflammatory pseudopolyps 47. Another distinct form of the post-inflammatory polyps is the bridged inflammatory pseudopolyp, representing a mucosal bridge that formed from a long filiform polyp connecting to the opposite end of the lumen 48.

Inflammatory pseudopolyp location and distribution

inflammatory pseudopolyps are more commonly encountered in large intestine, likely due to this tissue being affected in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The most common site is transverse colon and, thereafter, descending and sigmoid colon, with rectum being the least common site; moreover, inflammatory pseudopolyp in the rectum are usually found at the upper third region 30. The giant inflammatory pseudopolyps show similar topographic occurrence 47. However, as Crohn’s disease can involve the entire gastrointestinal tract, the inflammatory pseudopolyps can be present throughout but have been detected less often in extra-colonic regions. There is an exception to this distribution pattern for ulcerative colitis patients with backwash ileitis, wherein inflammatory pseudopolyps have also been found at the terminal ileum 49. There are also reports of inflammatory pseudopolyps located at the esophagus 50, stomach 51, and different parts of the small bowel 52, with ileum presentation predominating in the latter 53. There is one case report of a Crohn disease patient with pansinusitis location of inflammatory pseudopolyp, which regressed with medical therapy 54, and another case report of a patient with refractory pouchitis who presented with a large inflammatory pseudopolyp located in an affected pouch 55.

Pseudopolyps treatment

Questions remain about the optimal management or follow-up strategies for inflammatory pseudopolyp, especially for cases with multiple inflammatory pseudopolyp, because no large trials have been published regarding these issues.

A great matter of concern involves distinguishing them from adenoma-like dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM) and non-adenoma-like DALM (Figure 1H). Even though some diagnostic endoscopic criteria may be used for recognizing inflammatory pseudopolyp, they are not completely reliable 56. There can be good inter-observer agreement for identifying inflammatory pseudopolyp during endoscopy in general 57, but when it comes to distinguishing inflammatory pseudopolyp from other dysplastic lesions, the efficiency falls. Farraye et al 58 performed an internet-based study and found that gastroenterologists with non-inflammatory bowel disease-specialized expertise had lower capability of distinguishing different forms of lesions in inflammatory bowel disease patients.

Chromo-endoscopy might aid in differential diagnosis, since inflammatory pseudopolyps (as non-neoplastic polyps) show Kudo’s pattern classification of type II 59. In another study by Koinuma et al 60, magnifying endoscopy was demonstrated as a useful tool for distinguishing neoplastic from non-neoplastic lesions, reducing the amount of biopsies needed; however, the efficacy of this technique for studying the underlying inflammatory process was shown to be limited by the presence of multiple inflammatory pseudopolyps 56. In another study, 165 patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis were divided and randomized for endoscopic surveillance by means of either conventional endoscopy (with biopsies every 10 cm) or chromo-endoscopy (with 0.1% methylene blue); there were two false-negative results that were not identified by the chromo-endoscopy procedure, for which non-targeted biopsies from colons with multiple inflammatory pseudopolyp proved to contain dysplasia 61.

Nevertheless, in cases where there is either doubt about the diagnosis of inflammatory pseudopolyp, suspicion of DALM or large-size inflammatory pseudopolyp, or presence of multiple inflammatory pseudopolyp wherein endoscopic surveillance is compromised, multiple biopsies should be obtained in repeated examinations 62 or proceeding the endoscopic or surgical removal, with surrounding tissue examination by biopsy as well 63.

There is a general acceptance that if inflammatory pseudopolyp are adequately recognized using endoscopic criteria and do not provoke any complications, no removal is considered obligatory 58. However, it is considered mandatory that the surface of any inflammatory pseudopolyp be surveyed adequately during endoscopy. In older reports, especially of cases with large inflammatory pseudopolyp, surgical intervention was frequently performed for the removal, due to confusion with colorectal cancer or villous adenoma and related to the more common use of radiological approaches, such as barium enema, for diagnosis and monitoring 64. Nowadays, however, endoscopic surveillance is more effective than surgical intervention 65.

In the same context, the discovery of inflammatory pseudopolyp in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease, without evidence of suspicious lesions in endoscopy and in which the presence of inflammatory pseudopolyp does not obstruct adequate endoscopic surveillance of the mucosa, should not urge gastroenterologists towards more intense endoscopic follow-up. Neither should it discourage them from the use of chromo-endoscopy for surveillance in any manner other than those proposed in the various guidelines (with an approximate 3-year interval), and certainly not in a different way than would be performed in patients without inflammatory pseudopolyps 37. As mentioned before, colorectal cancer derived from inflammatory pseudopolyp is a rare event and occurrence of inflammatory pseudopolyp has not been linked with early colorectal cancer 66. Therefore, screening for colorectal cancer in all patients with inflammatory pseudopolyp is not recommended before 8-10 years after onset of symptoms 37.

Medical treatment has been used for inflammatory pseudopolyp and shown to induce regression. Choi et al 62 reported regression of giant inflammatory pseudopolyp in patients with inflammatory bowel disease upon administration of mesalazine and azathioprine. Infliximab has also been shown to induce regression of inflammatory pseudopolyp in Crohn’s disease 67. Topical enema with budenoside use was also reported to induce remission and control of minor bleeding of inflammatory pseudopolyp in sigmoid colon 68.

Endoscopic procedures such as argon plasma coagulation 69, endoscopic loop polypectomy 70, and ablation with yttrium aluminium garnet (commonly referred to as YAG) laser have been reported for control of bleeding provoked by ulcerated inflammatory pseudopolyp 71. Endoscopic resection with electrocautery is another effective means reported for removing either symptomatic inflammatory pseudopolyps or inflammatory pseudopolyps of which their benign nature was not able to be established only with endoscopic criteria and which need further histological evaluation 72.

Surgical methods are used when endoscopic therapy fails to manage complicated inflammatory pseudopolyp, for example in lower gastrointestinal bleeding or when obstructing phenomena, such as luminal obliteration or intussusception, occur 64. The various surgical procedures range from segmental dissection to hemicolectomy 73, depending on the cause. However, with the recent advances in endoscopic treatment, the need for a surgical approach has lessened over time.

References- Lumb G. Pathology of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1961;40:290–298.

- Ward, E. M. and Wolfsen, H. C. (2002), The non‐inherited gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 16: 333-342. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01172.x

- Goldgraber MB. Pseudopolyps in ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1965;8:355–363.

- Jalan KN, Walker RJ, Sircus W, McManus JP, Prescott RJ, Card WI. Pseudopolyposis in ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1969;2:555–559.

- Dukes CE. The surgical pathology of ulcerative colitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1954;14:389–400.

- Kelly JK, Langevin JM, Price LM, Hershfield NB, Share S, Blustein P. Giant and symptomatic inflammatory polyps of the colon in idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10:420–428.

- Politis DS, Katsanos KH, Tsianos EV, Christodoulou DK. Pseudopolyps in inflammatory bowel diseases: Have we learned enough?. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(9):1541–1551. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i9.1541 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5340806

- Crawford JC. The gastrointestinal tract. In: Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins, T, Robbins SL, eds. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1999: 775–843.

- Choi, C.R., Al Bakir, I., Ding, N.J. et al. Cumulative burden of inflammation predicts colorectal neoplasia risk in ulcerative colitis: a large single-centre study. Gut. 2019; 68: 414–422

- Maggs JR, Browning LC, Warren BF, Travis SP. Obstructing giant post-inflammatory polyposis in ulcerative colitis:Case report and review of the literature. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:170–180.

- Shergill AK, Lightdale JR, Bruining DH, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee. The role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1101–1121. e1-e13.

- Kelly JK, Gabos S. The pathogenesis of inflammatory polyps. Dis Colon Rectum 1987; 30: 251–4.

- No Association Between Pseudopolyps and Colorectal Neoplasia in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Mahmoud, Remi et al. Gastroenterology, Volume 156, Issue 5, 1333 – 1344.e3 https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.067

- Jalan KN, Walker RJ, Sircus W, et al. Pseudopolyposis in ulcerative colitis. Lancet 1969; 2: 555–9.

- Anderson R, Kaariainen IT, Hanauer SB. Protein‐losing enteropathy and massive pulmonary embolism in a patient with giant inflammatory polyposis and quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med 1996; 101: 323–5.

- Adelson JW, DeChadarevian JP, Azouz EM, et al. Giant inflammatory polyposis causing partial obstruction and pain in `healed’ ulcerative colitis in an adolescent. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1988; 7: 135–40.

- Koga H, Iida M, Aoyagi K, et al. Generalized giant inflammatory polyposis in a patient with ulcerative colitis presenting with protein‐losing enteropathy. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90: 829–31.

- Brozna JP, Fisher RL, Barwick KW. Filiform polyposis: an unusual complication of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 1985; 7: 451–8.

- Appelman HD, Threatt BA, Ernst C, et al. Filiform polyposis of the colon: an unusual sequel of ulcerative colitis [abstract]. Am J Clin Pathol 1974; 62: 145–6.

- Zegel HG, Laufer I. Filiform polyposis. Radiology 1978; 127: 615–9.

- Levine DS, Surawicz CM, Spencer GD, et al. Inflammatory polyposis two years after ischemic colon injury. Dig Dis Sci 1986; 31: 1159–67.

- Han JK, Kim SH, Choi BI, et al. Tuberculous colitis. Findings at double‐contrast barium enema examination. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 1204–9.

- Berkowitz D, Bernstein LH. Colonic pseudopolyps in association with amebic colitis. Gastroenterology 1975; 68: 786–9.

- Nebel OT, El‐Masry NA, Castell DO, et al. Schistosomal disease of the colon: a reversible form of polyposis. Gastroenterology 1974; 67: 939–43.

- Ladas SD, Savva S, Frydas A, et al. Invasive balantidiasis presented as chronic colitis and lung involvement. Dig Dis Sci 1989; 34: 1621–3.

- Masugi J, Matsui T, Fujimori T, et al. A case of Behcet’s disease with multiple longitudinal ulcers all over the colon. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89: 778–80.

- Woelfel GF, Campbell DN, Penn I, et al. Inflammatory polyposis in an ileal blind loop. Gastroenterology 1983; 84: 1020–4.

- Oriuchi T, Kinouchi Y, Kimura M, et al. Successful treatment of cap polyposis by avoidance of intraluminal trauma: clues to pathogenesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 2095–8.

- Williams GT, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. Inflammatory `cap’ polyposis of the large intestine [abstract]. Br J Surg 1985; 72: S133S133.

- De Dombal FT, Watts JM, Watkinson G, Goligher JC. Local complications of ulcerative colitis: stricture, pseudopolyposis, and carcinoma of colon and rectum. Br Med J. 1966;1:1442–1447.

- Bacon HE, Carroll PT, Cates BA, Mcgregor RA, Ouyang LM, Villalba G. Non-specific ulcerative colitis, with reference to mortality, morbidity, complications and long-term survivals following colectomy. Am J Surg. 1956;92:688–695.

- Teague RH, Read AE. Polyposis in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1975;16:792–795.

- Babic Z, Jagić V, Petrović Z, Bilić A, Dinko K, Kubat G, Troskot R, Vukelić M. Elevated serum values of procollagen III peptide (PIIIP) in patients with ulcerative colitis who will develop pseudopolyps. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:619–621.

- Keating JW, Mindell HJ. Localized giant pseudopolyposis in ulcerative colitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;126:1178–1180.

- Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, Dunlop MG, Thomas HJ, Evans GD, Eaden JA, Rutter MD, Atkin WP, Saunders BP, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002) Gut. 2010;59:666–689.

- Annese V, Daperno M, Rutter MD, Amiot A, Bossuyt P, East J, Ferrante M, Götz M, Katsanos KH, Kießlich R, et al. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:982–1018.

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee. Shergill AK, Lightdale JR, Bruining DH, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, et al. The role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1101–1121.e1-13.

- Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm MA, Williams CB, Price AB, Talbot IC, Forbes A. Cancer surveillance in longstanding ulcerative colitis: endoscopic appearances help predict cancer risk. Gut. 2004;53:1813–1816.

- Velayos FS, Loftus EV, Jess T, Harmsen WS, Bida J, Zinsmeister AR, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ. Predictive and protective factors associated with colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: A case-control study. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1941–1949.

- Baars JE, Looman CW, Steyerberg EW, Beukers R, Tan AC, Weusten BL, Kuipers EJ, van der Woude CJ. The risk of inflammatory bowel disease-related colorectal carcinoma is limited: results from a nationwide nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:319–328.

- Kusunoki M, Nishigami T, Yanagi H, Okamoto T, Shoji Y, Sakanoue Y, Yamamura T, Utsunomiya J. Occult cancer in localized giant pseudopolyposis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:379–381.

- Klarskov L, Mogensen AM, Jespersen N, Ingeholm P, Holck S. Filiform serrated adenomatous polyposis arising in a diverted rectum of an inflammatory bowel disease patient. APMIS. 2011;119:393–398.

- Jawad N, Graham T, Novelli M, Rodriguez-Justo M, Feakins R, Silver A, Wright N, McDonald S. PTU-124 Are pseudopolyps the source of tumorigenic mutations in ulcerative colitis? Gut. 2012;61(Suppl 2):A236.

- Hinrichs HR, Goldman H. Localized giant pseudopolyps of the colon. JAMA. 1968;205:248–249.

- Lim YJ, Choi JH, Yang CH. What is the Clinical Relevance of Filiform Polyposis? Gut Liver. 2012;6:524–526.

- Shah SM, Rogers HL, Nagai N. Localized giant pseudopolyposis in Crohn’s disease: colonoscopic findings. Dis Colon Rectum. 1978;21:104–106.

- Maggs JR, Browning LC, Warren BF, Travis SP. Obstructing giant post-inflammatory polyposis in ulcerative colitis: Case report and review of the literature. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:170–180.

- Van Moerkercke W, Deboever G, Lambrecht G, Hertveldt K. Severe bridging fibrosis of the colon in a man with inflammatory bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E294.

- Gardiner GA. “Backwash ileitis” with pseudopolyposis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;129:506–507.

- De Felice KM, Katzka DA, Raffals LE. Crohn’s Disease of the Esophagus: Clinical Features and Treatment Outcomes in the Biologic Era. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2106–2113.

- Zegel HG, Laufer I. Filiform polyposis. Radiology. 1978;127:615–619.

- Chang DK, Kim JJ, Choi H, Eun CS, Han DS, Byeon JS, Kim JO. Double balloon endoscopy in small intestinal Crohn’s disease and other inflammatory diseases such as cryptogenic multifocal ulcerous stenosing enteritis (CMUSE) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:S96–S98.

- Kahn E, Daum F. Pseudopolyps of the small intestine in Crohn’s disease. Hum Pathol. 1984;15:84–86.

- Ernst A, Preyer S, Plauth M, Jenss H. Polypoid pansinusitis in an unusual, extra-intestinal manifestation of Crohn disease. HNO. 1993;41:33–36.

- Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Delaney CP, Bennett AE, Achkar JP, Brzezinski A, Khandwala F, Liu W, Bambrick ML, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of inflammatory and noninflammatory sequelae of ileal pouch-anal anastomoses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:93–101.

- Bernstein CN. The color of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1135–1138.

- Thia KT, Loftus EV, Pardi DS, Kane SV, Faubion WA, Tremaine WJ, Schroeder KW, Harmsen SW, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. Measurement of disease activity in ulcerative colitis: interobserver agreement and predictors of severity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1257–1264.

- Farraye FA, Waye JD, Moscandrew M, Heeren TC, Odze RD. Variability in the diagnosis and management of adenoma-like and non-adenoma-like dysplasia-associated lesions or masses in inflammatory bowel disease: an Internet-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:519–529.

- Kudo S, Tamura S, Nakajima T, Yamano H, Kusaka H, Watanabe H. Diagnosis of colorectal tumorous lesions by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:8–14.

- Koinuma K, Togashi K, Konishi F, Kirii Y, Horie H, Okada M, Nagai H. Localized giant inflammatory polyposis of the cecum associated with distal ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:880–883.

- Kiesslich R, Fritsch J, Holtmann M, Koehler HH, Stolte M, Kanzler S, Nafe B, Jung M, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Methylene blue-aided chromoendoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:880–888.

- Choi YS, Suh JP, Lee IT, Kim JK, Lee SH, Cho KR, Park HJ, Kim DS, Lee DH. Regression of giant pseudopolyps in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:240–243.

- Itzkowitz SH, Harpaz N. Diagnosis and management of dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1634–1648.

- Biondi A, Persiani R, Paliani G, Mattana C, Vecchio FM, D’Ugo D. Giant inflammatory polyposis as the first manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2359–2360.

- Ooi BS, Tjandra JJ, Pedersen JS, Bhathal PS. Giant pseudopolyposis in inflammatory bowel disease. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:389–393.

- Baars JE, Kuipers EJ, van Haastert M, Nicolaï JJ, Poen AC, van der Woude CJ. Age at diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease influences early development of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a nationwide, long-term survey. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1308–1322.

- Liatsos C, Kyriakos N, Panagou E, Karagiannis S, Salemis N, Mavrogiannis C. Inflammatory polypoid mass treated with Infliximab in a Crohn’s disease patient. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:707–708.

- Pilichos C, Preza A, Demonakou M, Kapatsoris D, Bouras C. Topical budesonide for treating giant rectal pseudopolyposis. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:2961–2964.

- Attar A, Bon C, Sebbagh V, Béjou B, Bénamouzig R. Endoscopic argon plasma coagulation for the treatment of hemorrhagic pseudopolyps in colonic Crohn’s disease. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E249.

- Rutter M, Saunders B, Emmanuel A, Price A. Endoscopic snare polypectomy for bleeding postinflammatory polyps. Endoscopy. 2003;35:788–790.

- Forde KA, Green PH. Laser ablation of symptomatic rectal pseudopolyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:135.

- Corless JK, Tedesco FJ, Griffin JW, Panish JK. Giant ileal inflammatory polyps in Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984;30:352–354.

- Atten MJ, Attar BM, Mahkri MA, Del Pino A, Orsay CP. Giant pseudopolyps presenting as colocolic intussusception in Crohn’s colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1591–1592.