What is pyridoxine hydrochloride

Pyridoxine hydrochloride is the hydrochloride salt of pyridoxine, the alcohol form of vitamin B6. Pyridoxine hydrochloride is a hydrochloride and a vitamin B6. It contains a pyridoxine, a vitamin B6, which is an important water-soluble vitamin that is naturally present in many foods. The richest sources of vitamin B6 include fish, beef liver and other organ meats, potatoes and other starchy vegetables, and fruit (other than citrus) 1. In the United States, adults obtain most of their dietary vitamin B6 from fortified cereals, beef, poultry, starchy vegetables, and some non-citrus fruits 2, 3.

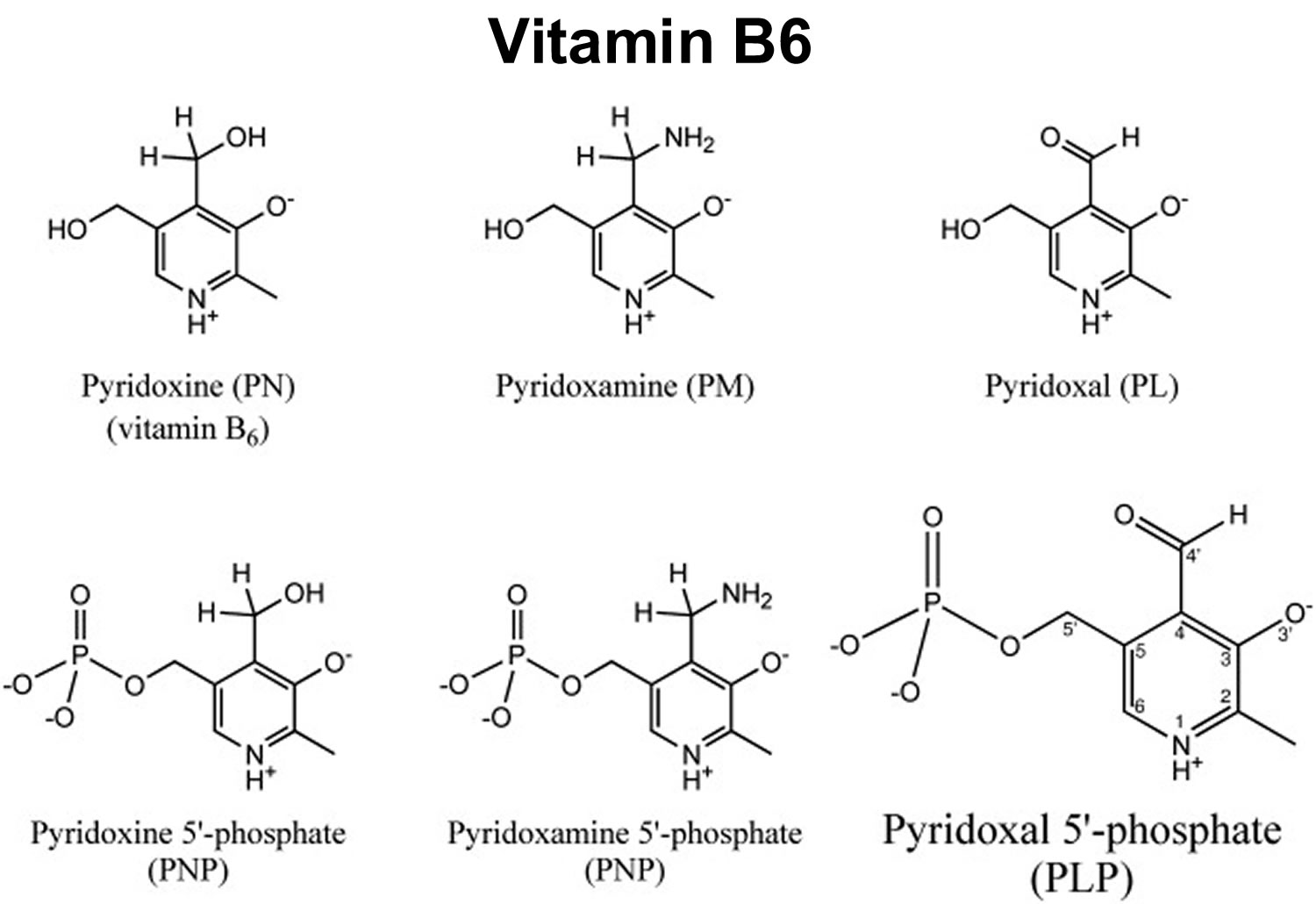

Vitamin B6 is a generic term for six compounds (vitamers) with vitamin B6 activity such as pyridoxine, pyridoxamine, pyridoxal and their phosphorylated derivatives, pyridoxine 5-phosphate (PNP), pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) and pyridoxamine 5-phosphate (PMP) (see Figure 1 below) 1. Although all six of these compounds (vitamers) should technically be referred to as vitamin B6, the term vitamin B6 is commonly used interchangeably with just one of them, pyridoxine.

Vitamin B6 must be obtained from the diet because humans cannot synthesize it 4. Pyridoxine, the 4-methanol form of vitamin B6, is converted into pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP), which is the active coenzyme form of vitamin B6 for synthesis of amino acids, hemogloblin, sphingomyelin and other sphingolipids, neurotransmitters (serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine and gamma-aminobutyric acid [GABA]), aminolevulinic acid, in addition to carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism (see Figure 1 below) 5, 6. Pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) is also involved in glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis 7, 8. Glycogenolysis is the biochemical pathway in which glycogen breaks down into glucose-1-phosphate and glucose, occurring in the liver when blood glucose levels drop; whereas gluconeogenesis is the synthesis of new glucose when dietary intake is insufficient or absent from non-carbohydrate sources like lactic acid, glycerol, amino acids and occurs in the liver.

The body needs vitamin B6 for more than 100 enzyme reactions, mostly concerned with protein metabolism 9. Vitamin B6 is also involved in brain development during pregnancy and infancy as well as immune function.

There are only two U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs containing pyridoxine or its analogs; the first is a combination of several vitamins, including B6, indicated for the prevention of vitamin deficiency in children and adult patients receiving parenteral nutrition, often called total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and the second is a combination of doxylamine succinate and pyridoxine hydrochloride (Bonjesta or Diclegis) in oral tablet form for treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy that does not respond to conservative management 10, 11.

Pyridoxine is also used to treat vitamin B6 deficiency, which may be due to poor kidney function, autoimmune diseases, increased alcohol intake, or isoniazid, cycloserine, valproic acid, phenytoin, carbamazepine, primidone, hydralazine, and theophylline therapy 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. Inadequate vitamin B6 intake is a rare cause of its deficiency, because most children, adolescents, and adults in the United States consume the recommended amounts of vitamin B6, according to an analysis of data from the 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 19. The average vitamin B6 intake is about 1.5 mg/day in women and 2 mg/day in men 9.

Most people in the United States get enough vitamin B6 from the foods they eat. However, certain groups of people are more likely than others to have trouble getting enough vitamin B6 20:

- People whose kidneys do not work properly, including people who are on kidney dialysis and those who have had a kidney transplant.

- People with autoimmune disorders, which cause their immune system to mistakenly attack their own healthy tissues. For example, people with rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or inflammatory bowel disease sometimes have low vitamin B6 levels.

- People with alcohol dependence.

Vitamin B6 deficiency can be observed clinically as seborrheic dermatitis, microcytic anemia, dental decay, glossitis, epileptiform convulsions, peripheral neuropathy, electroencephalographic abnormalities, depression, confusion, and weakened immune function 12, 21, 22, 23, 24.

Some rare inborn errors of metabolism result from defects in the coenzyme binding sites of the responsible enzymes where pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) is attached, and administering very high doses of vitamin B6 is crucial for the functioning of these enzymes 25. These disorders are called vitamin B6 dependency syndromes. Examples of these syndromes are convulsions of the newborn, xanthurenic aciduria, cystathioninuria, primary hyperoxaluria, homocystinuria, sideroblastic anemia, and gyrate atrophy with ornithinuria 25.

Furthermore, some toxicological uses of pyridoxine include isoniazid overdose, false morel (gyromitra) mushroom poisoning, hydrazine exposure, ethylene glycol toxicity, and crimidin toxicity 18.

There is some proof of Vitamin B6 having effectiveness in suppressing lactation and relieving side effects of oral contraceptives such as depression and nausea 26.

Research has found conflicting results regarding the use of vitamin B6 supplements in treating gestational diabetes, premenstrual syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, morning sickness, and treating and preventing essential hypertension 26.

Even though scant evidence regarding pyridoxine’s efficacy exists regarding these uses, it has been used empirically to treat some conditions, including atopic dermatitis, dental caries, acute alcohol intoxication, autism, diabetic complications, Down syndrome, schizophrenia, Huntington chorea, and steroid-dependent asthma 26, 21, 23, 27, 12.

Research shows a decreased risk of colorectal cancer with increased B6 intake in humans 28. Some research has shown high B6 levels to inhibit in-vitro (test tube studies) hepatic tumor cell multiplication in rats 29.

Vitamin B6 is available in multivitamins, in supplements containing other B complex vitamins, and as a stand-alone supplement 1. The most common vitamin B6 vitamer in supplements is pyridoxine (in the form of pyridoxine hydrochloride [HCl]), although some supplements contain pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP).

Pyridoxine comes in regular and extended-release (long-acting) tablets. It usually is taken once a day. Follow the directions on your prescription label or package label carefully, and ask your doctor or pharmacist to explain any part you do not understand. Take pyridoxine exactly as directed. Do not take more or less of it or take it more often than prescribed by your doctor.

Do not chew, crush, or cut extended-release tablets; swallow them whole.

Vitamin B6 supplements are available in oral capsules or tablets (including sublingual and chewable tablets) and liquids. Absorption of vitamin B6 from supplements is similar to that from food sources and does not differ substantially among the various forms of supplements 9. Although the body absorbs large pharmacological doses of vitamin B6 well, it quickly eliminates most of the vitamin in the urine 30.

The human body absorbs vitamin B6 in the jejunum. Phosphorylated forms of the vitamin are dephosphorylated, and the pool of free vitamin B6 is absorbed by passive diffusion 5.

Vitamin B6 concentrations can be measured directly by assessing concentrations of pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP); other vitamers; or total vitamin B6 in plasma, erythrocytes, or urine 9. Vitamin B6 concentrations can also be measured indirectly by assessing either erythrocyte aminotransferase saturation by pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) or tryptophan metabolites. Plasma pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) is the most common measure of vitamin B6 status.

Pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) concentrations of more than 30 nmol/L have been traditional indicators of adequate vitamin B6 status in adults 2. However, the Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) at the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies used a plasma PLP level of 20 nmol/L as the major indicator of adequacy to calculate the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for adults 2.

Figure 1. Vitamin B6 chemical structures

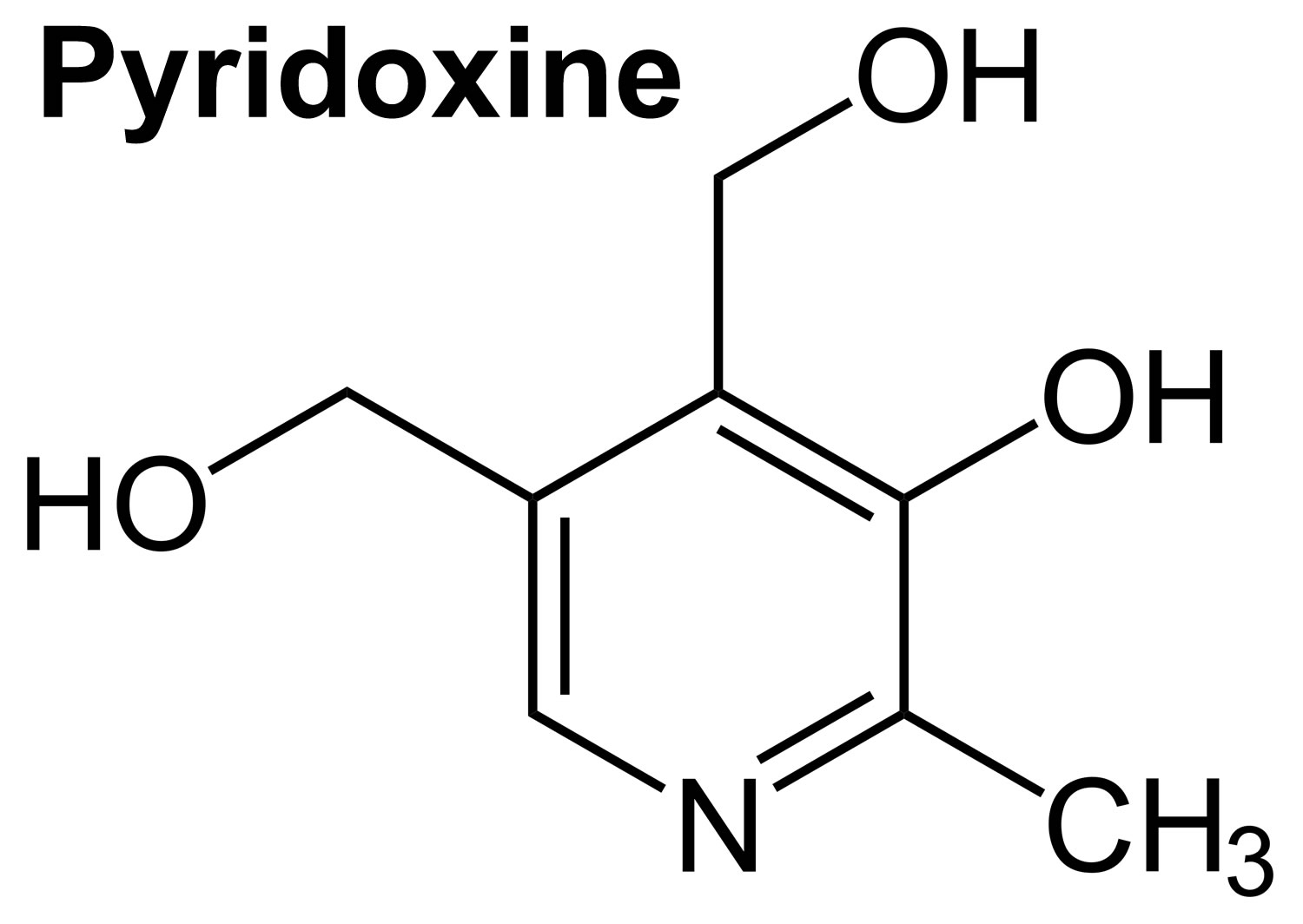

[Source 31 ]Figure 2. Pyridoxine

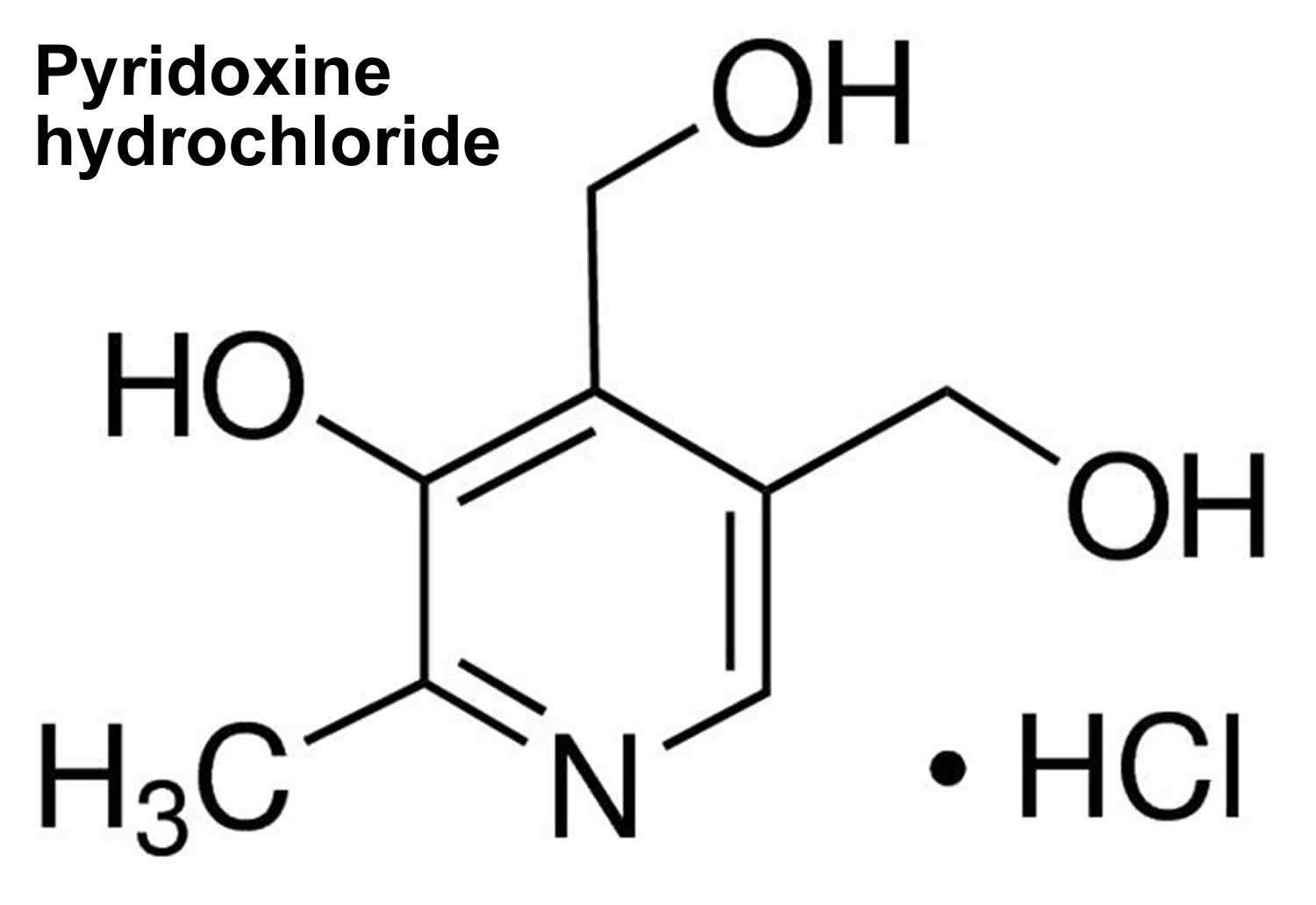

Figure 3. Pyridoxine hydrochloride

What happens if I don’t get enough vitamin B6?

Vitamin B6 deficiency is uncommon in the United States. People who don’t get enough vitamin B6 can have a range of symptoms, including anemia, itchy rashes, scaly skin on the lips, sores or ulcers of the mouth, and ulcers of the skin at the corners of the mouth and inflammation of the tongue 32. Other symptoms of very low vitamin B6 levels include irritability, depression, confusion and a weak immune system 32. Infants who do not get enough vitamin B6 can become irritable or develop extremely sensitive hearing or seizures. In the early 1950s, seizures were observed in infants as a result of severe vitamin B6 deficiency caused by an error in the manufacture of infant formula 16. Abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG) patterns have also been reported in vitamin B6-deficient adults.

What are some effects of vitamin B6 on health?

Scientists are studying vitamin B6 to understand how it affects health. Here are some examples of what this research has shown.

Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy

At least half of all women experience nausea, vomiting, or both in the first few months of pregnancy 33, 34. Although this condition is generally known as “morning sickness,” it often lasts throughout the day. The condition is not life threatening and typically goes away after 12–20 weeks, but its symptoms can disrupt a person’s social and physical functioning.

Prospective studies on vitamin B6 supplements to treat morning sickness have had mixed results. In two randomized, placebo-controlled trials, 30–75 mg of oral pyridoxine per day significantly decreased nausea in pregnant people who were experiencing nausea 35, 36. The authors of a recent Cochrane review of studies on interventions for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy could not draw firm conclusions on the value of vitamin B6 to control the symptoms of morning sickness 34.

Randomized trials have shown that a combination of vitamin B6 and doxylamine (an antihistamine) is associated with a 70% reduction in nausea and vomiting in pregnant individuals and lower hospitalization rates for this problem 33, 37.

Based on the results of several studies, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends under a doctor’s care taking 10–25 mg of vitamin B6 three or four times a day to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy 37. If the patient’s condition does not improve, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends adding doxylamine. Before taking a vitamin B6 supplement, pregnant people should consult a physician because doses could approach the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) (see Table 3 below).

Premenstrual syndrome

Some evidence suggests that vitamin B6 supplements could reduce the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS), but conclusions are limited due to the poor quality of most studies 38. A meta-analysis of nine published trials involving almost 1,000 women with PMS found that vitamin B6 is more effective in reducing PMS symptoms than placebo, but most of the studies analyzed were small and several had methodological weaknesses 38. A more recent double-blind, randomized controlled trial in 94 women found that 80 mg pyridoxine taken daily over the course of three cycles was associated with statistically significant reductions in a broad range of PMS symptoms, including moodiness, irritability, forgetfulness, bloating, and, especially, anxiety 39. The potential effectiveness of vitamin B6 in alleviating the mood-related symptoms of PMS could be due to its role as a cofactor in neurotransmitter biosynthesis 40. Although vitamin B6 shows promise for alleviating PMS symptoms, more research is needed before drawing firm conclusions.

Cardiovascular disease

Some scientists have hypothesized that certain B vitamins (such as folic acid, vitamin B12, and vitamin B6) might reduce cardiovascular disease risk by lowering levels of homocysteine, an amino acid in the blood 41. Therefore, several clinical trials have assessed the safety and efficacy of supplemental doses of B vitamins to reduce heart disease risk. For example, the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation 2 (HOPE 2) trial, which included more than 5,500 adults with known cardiovascular disease, found that supplementation for 5 years with vitamin B6 (50 mg/day), vitamin B12 (1 mg/day), and folic acid (2.5 mg/day) reduced homocysteine levels and decreased stroke risk by about 25%, but the study did not include a separate vitamin B6 group 42. Evaluating the impact of vitamin B6 from many of these trials is challenging because these studies also included folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation.

Moreover, most other large clinical trials have failed to demonstrate that supplemental B vitamins actually reduce the risk of cardiovascular events, even though they lower homocysteine levels. For example, a randomized clinical trial in 5,442 women aged 42 or older found no effect of vitamin B6 supplementation (50 mg/day) in combination with 2.5 mg folic acid and 1 mg vitamin B12 on cardiovascular disease risk 43. Two large randomized controlled trials, the Norwegian Vitamin Trial and the Western Norway B Vitamin Intervention Trial, did include a group that received only vitamin B6 supplements (40 mg/day). The combined analysis of data from these two trials showed no benefit of vitamin B6 supplementation, with or without folic acid (0.8 mg/day) plus vitamin B12 (0.4 mg/day), on major cardiovascular events in 6,837 patients with ischemic heart disease 41. In a trial of adults who had suffered a nondisabling stroke, supplementation with high or low doses of a combination of vitamins B6 and B12 and folic acid for 2 years had no effect on subsequent stroke incidence, cardiovascular events, or risk of death 44.

In summary, although vitamin B supplements do lower blood homocysteine, research shows that supplemental amounts of vitamin B6, alone or with folic acid and vitamin B12 do not actually reduce the risk or severity of heart disease or stroke.

Cancer

Some research has associated low plasma vitamin B6 concentrations with an increased risk of certain kinds of cancer, such as colorectal cancer 2. For example, a meta-analysis of prospective studies found that people with a vitamin B6 intake in the highest quintile had a 20% lower risk of colorectal cancer than those with an intake in the lowest quintile 28.

However, the small number of clinical trials completed to date have not shown that vitamin B6 supplementation can help prevent cancer or reduce the chances of dying from this disease. For example, an analysis of data from two large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in Norway found no association between vitamin B6 supplementation and cancer incidence, mortality, or all-cause mortality 45.

Cognitive function

Some research indicates that elderly people who have higher blood levels of vitamin B6 have better memory 46. Several studies have demonstrated an association between vitamin B6 and brain function in the elderly. For example, an analysis of data from the Boston Normative Aging Study found associations between higher serum vitamin B6 concentrations and better memory test scores in 70 men aged 54–81 years 47.

However, a systematic review of 14 randomized controlled trials found insufficient evidence of an effect of vitamin B6 supplementation alone or in combination with vitamin B12 and/or folic acid on cognitive function in people with normal cognitive function, dementia, or ischemic vascular disease 46. According to this review, most of the studies were of low quality and limited applicability. A Cochrane review found no evidence that short-term vitamin B6 supplementation (for 5–12 weeks) improves cognitive function or mood in the two studies that the authors evaluated 48. The review did find some evidence that daily vitamin B6 supplements (20 mg) can affect biochemical indices of vitamin B6 status in healthy older men, but these changes had no overall impact on cognition.

More evidence is needed to determine whether vitamin B6 supplements might help prevent or treat cognitive decline in elderly people.

Depression

The importance of pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes in the synthesis of several neurotransmitters (serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine and gamma-aminobutyric acid [GABA]) has led researchers to consider whether vitamin B6 deficiency may contribute to the onset of depressive symptoms. There is limited evidence suggesting that supplemental vitamin B6 may have therapeutic efficacy in the management of depression. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted in 225 elderly patients hospitalized for acute illness, a six-month intervention with daily multivitamin/mineral supplements improved nutritional B-vitamin status and decreased the number and severity of depressive symptoms when compared to placebo 49. In addition, while supplement intake effectively reduced plasma homocysteine levels compared to placebo, the effect of supplementation on depressive symptoms at the end of the trial was greater in treated subjects in the lowest versus highest quartile of homocysteine levels (≤10 micromoles/liter vs. ≥16.1 micromoles/liter) 50. Yet, the cause of late-onset depression is unclear and evidence is currently lacking to suggest whether supplemental B vitamins (including vitamin B6) could relieve depressive symptoms.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Carpal tunnel syndrome causes numbness, pain, and weakness of the hand and fingers due to compression of the median nerve at the wrist. It may result from repetitive stress injury of the wrist or from soft-tissue swelling, which sometimes occurs with pregnancy or hypothyroidism. Early studies by the same investigator suggested that supplementation with 100-200 mg/day of vitamin B6 for several months might improve carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms in individuals with low vitamin B6 status 51, 52. In addition, a cross-sectional study in 137 men not taking vitamin supplements found that decreased blood levels of pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) were associated with increased pain, tingling, and nocturnal awakening—all symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome 53. However, studies using electrophysiological measurements of median nerve conduction have largely failed to find an association between vitamin B6 deficiency and carpal tunnel syndrome 54. While a few studies have noted some symptomatic relief with vitamin B6 supplementation, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have not generally found vitamin B6 to be effective in treating carpal tunnel syndrome 54. Yet, despite its equivocal effectiveness, vitamin B6 supplementation is sometimes used in complementary therapy in an attempt to avoid hand surgery. Patients taking high doses of vitamin B6 should be advised by a physician and monitored for vitamin B6-related toxicity symptoms 55.

Kidney stones

A large prospective study examined the relationship between vitamin B6 intake and the occurrence of symptomatic kidney stones in women 56. A group of more than 85,000 women without a prior history of kidney stones were followed over 14 years, and those who consumed 40 mg or more of vitamin B6 daily had only two-thirds the risk of developing kidney stones compared with those who consumed 3 mg or less 56. However, in a group of more than 45,000 men followed for 14 years, no association was found between vitamin B6 intake and the occurrence of kidney stones 57. Limited experimental data have suggested that supplementation with high doses of pyridoxamine may help decrease the formation of calcium oxalate kidney stones and reduce urinary oxalate levels, an important determinant of calcium oxalate kidney stone formation 58, 59. Presently, the relationship between vitamin B6 intake and the risk of developing kidney stones requires further study before any recommendations can be made.

Pyridoxine hydrochloride in food

Vitamin B6 is found naturally in a wide variety of foods and is added to other foods 2. The richest sources of vitamin B6 include fish, beef liver and other organ meats, potatoes and other starchy vegetables, and fruit (other than citrus). You can get recommended amounts of vitamin B6 by eating a variety of foods, including the following 20:

- Poultry, fish, and organ meats, all rich in vitamin B6.

- Potatoes and other starchy vegetables, which are some of the major sources of vitamin B6 for Americans.

- Fruit (other than citrus), which are also among the major sources of vitamin B6 for Americans.

In the United States, adults obtain most of their dietary vitamin B6 from fortified cereals, beef, poultry, starchy vegetables, and some non-citrus fruits 2. About 75% of vitamin B6 from a mixed diet is bioavailable 9.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) FoodData Central (https://fdc.nal.usda.gov) lists the nutrient content of many foods and provides a comprehensive list of foods containing vitamin B6 arranged by nutrient content (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/VitaminB6-Content.pdf) and by food name (https://ods.od.nih.gov/pubs/usdandb/VitaminB6-Food.pdf).

Table 1. Vitamin B6 content of selected foods

| Food | Milligrams (mg) per serving | Percent DV* |

|---|---|---|

| Chickpeas, canned, 1 cup | 1.1 | 65 |

| Beef liver, pan fried, 3 ounces | 0.9 | 53 |

| Tuna, yellowfin, fresh, cooked, 3 ounces | 0.9 | 53 |

| Salmon, sockeye, cooked, 3 ounces | 0.6 | 35 |

| Chicken breast, roasted, 3 ounces | 0.5 | 29 |

| Breakfast cereals, fortified with 25% of the DV for vitamin B6 | 0.4 | 25 |

| Potatoes, boiled, 1 cup | 0.4 | 25 |

| Turkey, meat only, roasted, 3 ounces | 0.4 | 25 |

| Banana, 1 medium | 0.4 | 25 |

| Marinara (spaghetti) sauce, ready to serve, 1 cup | 0.4 | 25 |

| Ground beef, patty, 85% lean, broiled, 3 ounces | 0.3 | 18 |

| Waffles, plain, ready to heat, toasted, 1 waffle | 0.3 | 18 |

| Bulgur, cooked, 1 cup | 0.2 | 12 |

| Cottage cheese, 1% low-fat, 1 cup | 0.2 | 12 |

| Squash, winter, baked, ½ cup | 0.2 | 12 |

| Rice, white, long-grain, enriched, cooked, 1 cup | 0.1 | 6 |

| Nuts, mixed, dry-roasted, 1 ounce | 0.1 | 6 |

| Raisins, seedless, ½ cup | 0.1 | 6 |

| Onions, chopped, ½ cup | 0.1 | 6 |

| Spinach, frozen, chopped, boiled, ½ cup | 0.1 | 6 |

| Tofu, raw, firm, prepared with calcium sulfate, ½ cup | 0.1 | 6 |

| Watermelon, raw, 1 cup | 0.1 | 6 |

Footnotes: *DV = Daily Value. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) developed DVs to help consumers compare the nutrient contents of foods and dietary supplements within the context of a total diet. The DV for vitamin B6 is 1.7 mg for adults and children age 4 years and older. FDA does not require food labels to list vitamin B6 content unless vitamin B6 has been added to the food. Foods providing 20% or more of the DV are considered to be high sources of a nutrient, but foods providing lower percentages of the DV also contribute to a healthful diet.

[Source 1 ]How much vitamin B6 do I need?

The amount of vitamin B6 you need depends on your age. Average daily recommended amounts are listed below in milligrams (mg).

Table 2. Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for Vitamin B6

| Life Stage | Recommended Amount |

|---|---|

| Birth to 6 months | 0.1 mg |

| Infants 7–12 months | 0.3 mg |

| Children 1–3 years | 0.5 mg |

| Children 4–8 years | 0.6 mg |

| Children 9–13 years | 1.0 mg |

| Teens 14–18 years (boys) | 1.3 mg |

| Teens 14–18 years (girls) | 1.2 mg |

| Adults 19–50 years | 1.3 mg |

| Adults 51+ years (men) | 1.7 mg |

| Adults 51+ years (women) | 1.5 mg |

| Pregnant teens and women | 1.9 mg |

| Breastfeeding teens and women | 2.0 mg |

Footnote: Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) is the average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97%–98%) healthy individuals; often used to plan nutritionally adequate diets for individuals.

[Source 20 ]Pyridoxine hydrochloride uses

There are only two U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs containing pyridoxine or its analogs; the first is a combination of several vitamins, including B6, indicated for the prevention of vitamin deficiency in children and adult patients receiving parenteral nutrition, often called total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and the second is a combination of doxylamine succinate and pyridoxine hydrochloride (Bonjesta or Diclegis) in oral tablet form for treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (often referred to as morning sickness) that does not respond to conservative management 10, 11.

Pyridoxine is also used to treat vitamin B6 deficiency, which may be due to poor kidney function, autoimmune diseases, increased alcohol intake, or isoniazid, cycloserine, valproic acid, phenytoin, carbamazepine, primidone, hydralazine, and theophylline therapy 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. Inadequate vitamin B6 intake is a rare cause of its deficiency, because most children, adolescents, and adults in the United States consume the recommended amounts of vitamin B6, according to an analysis of data from the 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 19. The average vitamin B6 intake is about 1.5 mg/day in women and 2 mg/day in men 9.

A few rare inborn metabolic disorders, including pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy and pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate oxidase deficiency, are the cause of early-onset epileptic encephalopathies that are found to be responsive to pharmacologic doses of vitamin B6. In individuals affected by pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy and pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate oxidase deficiency, pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) bioavailability is limited, and treatment with pyridoxine and/or pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) have been used to alleviate or abolish epileptic seizures characterizing these conditions 60. Pyridoxine therapy, along with dietary protein restriction, is also used in the management of vitamin B6 responsive homocystinuria caused by the deficiency of the pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzyme, cystathionine β synthase 61.

Is pyridoxine hydrochloride safe?

When taken by mouth vitamin B6 is likely safe when used appropriately. Taking vitamin B6 in doses of 100 mg daily or less is generally considered to be safe. Vitamin B6 is possibly safe when taken in doses of 101-200 mg daily. In some people, vitamin B6 might cause nausea, stomach pain, loss of appetite, headache, and other side effects. Vitamin B6 is possibly unsafe when taken in doses of 500 mg or more daily. High doses of vitamin B6, especially 1000 mg or more daily, might cause brain and nerve problems.

The Institute of Medicine’s Food and Nutrition Board has established Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for vitamin B6 that apply to both food and supplement intakes (Table 3) 9. The Institute of Medicine’s Food and Nutrition Board noted that although several reports show sensory neuropathy occurring at doses lower than 500 mg/day, studies in patients treated with vitamin B6 (average dose of 200 mg/day) for up to 5 years found no evidence of this effect. Based on limitations in the data on potential harms from long-term use, the Institute of Medicine’s Food and Nutrition Board halved the dose used in these studies to establish a Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) of 100 mg/day for adults. Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (ULs) are lower for children and adolescents based on body size. The Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (ULs) do not apply to individuals receiving vitamin B6 for medical treatment, but such individuals should be under the care of a physician.

Table 3. Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (ULs) for Vitamin B6

| Age | Male | Female | Pregnancy | Lactation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth to 6 months | Not possible to establish* | Not possible to establish* | ||

| 7–12 months | Not possible to establish* | Not possible to establish* | ||

| 1–3 years | 30 mg | 30 mg | ||

| 4–8 years | 40 mg | 40 mg | ||

| 9–13 years | 60 mg | 60 mg | ||

| 14–18 years | 80 mg | 80 mg | 80 mg | 80 mg |

| 19+ years | 100 mg | 100 mg | 100 mg | 100 mg |

Footnote: Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) is the Maximum daily intake unlikely to cause adverse health effects.

*Breast milk, formula, and food should be the only sources of vitamin B6 for infants.

[Source 1 ]Contraindications

The only two contraindications for vitamin B6 are hypervitaminosis B6, as toxic levels may cause sensory neuropathy and hypersensitivity to pyridoxine.

High intakes of vitamin B6 from food sources have not been reported to cause adverse effects 9. However, chronic administration of 1–6 g oral pyridoxine per day for 12–40 months can cause severe and progressive sensory neuropathy characterized by ataxia (loss of control of bodily movements) 62, 63. The degeneration of sensory fibers of peripheral nerves and its myelin and also the dorsal columns of the spinal cord cause bilateral loss of peripheral sensation or hyperaesthesia, accompanied by limb pain, ataxia, and loss of balance. Symptom severity appears to be dose dependent, and the symptoms usually stop if the patient discontinues the pyridoxine supplements as soon as the neurologic symptoms appear 18. Other effects of excessive vitamin B6 intakes include painful, disfiguring dermatological lesions; photosensitivity; gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea and heartburn; testicular atrophy and reduced sperm motility 64, 5, 27.

Research on the subject found that the duration of administration of vitamin B6 is directly proportional to the risk of clinically evident toxicity with respect to the total dose given 27.

Special precautions and warnings

- Post-surgical stent placement. Avoid using a combination of vitamin B6, folate, and vitamin B12 after receiving a coronary stent. This combination may increase the risk of blood vessel narrowing.

- Weight loss surgery. Taking a vitamin B6 supplement is not needed for people that have had weight loss surgery. Taking too much might increase the chance of side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and browning skin.

Pregnancy

Vitamin B6 is likely safe when taken by mouth, appropriately. It’s sometimes used to control morning sickness, but should only be done so under the supervision of a healthcare provider. Taking high doses is possibly unsafe. High doses might cause newborns to have seizures.

Breast-feeding

Vitamin B6 is likely safe when taken in doses of 2 mg by mouth daily. Avoid using higher amounts. There isn’t enough reliable information to know if taking higher doses of vitamin B6 is safe when breast-feeding.

Interactions with medications

- Do not take vitamin B6 (pyridoxine hydrochloride) with phenytoin (Dilantin). Vitamin B6 might increase how quickly the body breaks down phenytoin. Taking vitamin B6 along with phenytoin might decrease the effects of phenytoin and increase the risk of seizures. Do not take large doses of vitamin B6 if you are taking phenytoin.

- Be cautious with taking vitamin B6 (pyridoxine hydrochloride) with this:

- Amiodarone (Cordarone). Amiodarone might increase sensitivity to sunlight. Taking vitamin B6 along with amiodarone might increase the chances of sunburn, blistering, or rashes on areas of skin exposed to sunlight. Be sure to wear sunblock and protective clothing when spending time in the sun.

- Medications for high blood pressure (antihypertensive drugs). Vitamin B6 might lower blood pressure. Taking vitamin B6 along with medications that lower blood pressure might cause blood pressure to go too low. Monitor your blood pressure closely.

- Phenobarbital (Luminal). Vitamin B6 might increase how quickly the body breaks down phenobarbital. This could decrease the effects of phenobarbital.

- Vitamin B6 supplements might interact with cycloserine (Seromycin®), an antibiotic used to treat tuberculosis. In combination with pyridoxal phosphate, cycloserine increases urinary excretion of pyridoxine 65. The urinary loss of pyridoxine might exacerbate the seizures and neurotoxicity associated with cycloserine. Pyridoxine supplements can help prevent these adverse effects.

- Taking certain epilepsy drugs could decrease vitamin B6 levels and reduce the drugs’ ability to control seizures. Some antiepileptic drugs, including valproic acid (Depakene®, Stavzor®), carbamazepine (Carbatrol®, Epitol®, Tegretol®, and others), and phenytoin (Dilantin®) increase the catabolism rate of vitamin B6 vitamers, resulting in low plasma pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) concentrations and hyperhomocysteinemia 17. High homocysteine levels in antiepileptic drug users might increase the risk of epileptic seizures and systemic vascular events, including stroke, and reduce the ability to control seizures in patients with epilepsy. Furthermore, patients typically use antiepileptic drugs for years, increasing their risk of chronic vascular toxicity. Some research also indicates that pyridoxine supplementation (200 mg/day for 12–120 days) can reduce serum concentrations of phenytoin and phenobarbital, possibly by increasing the drugs’ metabolism 26, 66. Whether lower pyridoxine doses have any effect is not known 65. Levetiracetam (Keppra®) is an antiepileptic medication with behavioral side effects that include irritability, agitation, and depression 67. Preliminary evidence suggests that vitamin B6 supplementation—at such doses as 50–350 mg/day in children 67 and 50–100 mg/day in adults 68 might reduce these side effects.

- Taking theophylline (Aquaphyllin®, Elixophyllin®, Theolair®, Truxophyllin®, and many others) for asthma or another lung disease can reduce vitamin B6 levels and cause seizures. Theophylline (Aquaphyllin®, Elixophyllin®, Theolair®, Truxophyllin®, and many others) can prevent or treat shortness of breath, wheezing, and other breathing problems caused by asthma, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and other lung diseases. Patients treated with theophylline often have low plasma pyridoxal 5-phosphate (PLP) concentrations, which could contribute to the neurological and central nervous system side effects associated with theophylline, including seizures 65, 26.

- Be watchful with taking vitamin B6 (pyridoxine hydrochloride) with this:

- Levodopa. Vitamin B6 can increase how quickly the body breaks down and gets rid of levodopa. But this is only a problem if you are taking levodopa alone. Most people take levodopa along with carbidopa. Carbidopa prevents this interaction from occurring. If you are taking levodopa without carbidopa, do not take vitamin B6.

- Herbs and supplements that might lower blood pressure

- Vitamin B6 might lower blood pressure. Taking it with other supplements that have the same effect might cause blood pressure to drop too much. Examples of supplements with this effect include andrographis, casein peptides, L-arginine, niacin, and stinging nettle.

Pyridoxine hydrochloride side effects

There are no reported adverse effects caused by dietary concentrations nor by regular supplemental doses of vitamin B6, while higher doses below levels of toxicity may cause indigestion, nausea, breast tenderness, photosensitivity, and vesicular dermatoses 69.

The most known side effect of vitamin B6 supplementation is sensory neuropathy, but this pathology rarely occurs below toxic doses, which is 1000 mg/day or more for adults and there is no evidence of its occurrence in doses lower than 100 mg/day for less than 30 weeks in adults 69. It is worth noting that the average dietary requirement of vitamin B6 for adults is 1.75 mg/day 25.

Common side effects of pyridoxine may include:

- nausea;

- headache;

- drowsiness;

- mild numbness or tingling.

This is not a complete list of side effects and others may occur. Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects.

Get emergency medical help if you have signs of an allergic reaction: hives; difficult breathing; swelling of your face, lips, tongue, or throat.

Pyridoxine may cause serious side effects. Call your doctor at once if you have:

- decreased sensation to touch, temperature, and vibration;

- loss of balance or coordination;

- numbness in your feet or around your mouth;

- clumsiness in your hands;

- feeling tired.

- Vitamin B6. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminB6-HealthProfessional

- Mackey A, Davis S, Gregory J. Vitamin B6. In: Shils M, Shike M, Ross A, Caballero B, Cousins R, eds. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 10th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Kahle LL. Dietary sources of nutrients among US adults, 1989 to 1991. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998 May;98(5):537-47. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00122-9

- Abosamak NER, Gupta V. Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) [Updated 2022 May 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557436

- McCormick D. Vitamin B6. In: Bowman B, Russell R, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. 9th ed. Washington, DC: International Life Sciences Institute; 2006.

- SNELL EE. Chemical structure in relation to biological activities of vitamin B6. Vitam Horm. 1958;16:77-125. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60314-3

- Ebadi M. Regulation and function of pyridoxal phosphate in CNS. Neurochem Int. 1981;3(3-4):181-205. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(81)90001-2

- SNELL EE. Summary of known metabolic functions of nicotinic acid, riboflavin and vitamin B6. Physiol Rev. 1953 Oct;33(4):509-24. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1953.33.4.509

- Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes: Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/6015/chapter/1

- Matthews A, Haas DM, O’Mathúna DP, Dowswell T, Doyle M. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Mar 21;(3):CD007575. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007575.pub3. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD007575

- Wibowo, N., Purwosunu, Y., Sekizawa, A., Farina, A., Tambunan, V. and Bardosono, S. (2012), Vitamin B6 supplementation in pregnant women with nausea and vomiting. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 116: 206-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.09.030

- Vech RL, Lumeng L, Li TK. Vitamin B6 metabolism in chronic alcohol abuse The effect of ethanol oxidation on hepatic pyridoxal 5′-phosphate metabolism. J Clin Invest. 1975 May;55(5):1026-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC301849/pdf/jcinvest00169-0160.pdf

- Snider DE Jr. Pyridoxine supplementation during isoniazid therapy. Tubercle. 1980 Dec;61(4):191-6. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(80)90038-0

- Raskin NH, Fishman RA. Pyridoxine-deficiency neuropathy due to hydralazine. N Engl J Med. 1965 Nov 25;273(22):1182-5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196511252732203

- Nair S, Maguire W, Baron H, Imbruce R. The effect of cycloserine on pyridoxine-dependent metabolism in tuberculosis. J Clin Pharmacol. 1976 Aug-Sep;16(8-9):439-43. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1976.tb02419.x

- Clayton PT. B6-responsive disorders: a model of vitamin dependency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006 Apr-Jun;29(2-3):317-26. doi: 10.1007/s10545-005-0243-2

- Apeland T, Frøyland ES, Kristensen O, Strandjord RE, Mansoor MA. Drug-induced pertubation of the aminothiol redox-status in patients with epilepsy: improvement by B-vitamins. Epilepsy Res. 2008 Nov;82(1):1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.06.003

- Lheureux P, Penaloza A, Gris M. Pyridoxine in clinical toxicology: a review. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005 Apr;12(2):78-85. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200504000-00007

- Martha Savaria Morris, Mary Frances Picciano, Paul F Jacques, Jacob Selhub, Plasma pyridoxal 5′-phosphate in the US population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2004, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 87, Issue 5, May 2008, Pages 1446–1454, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1446

- Vitamin B6. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminB6-Consumer

- MUELLER JF, VILTER RW. Pyridoxine deficiency in human beings induced with desoxypyridoxine. J Clin Invest. 1950 Feb;29(2):193-201. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC439740/pdf/jcinvest00403-0053.pdf

- Hawkins WW, Barsky J. An Experiment on Human Vitamin B6 Deprivation. Science. 1948 Sep 10;108(2802):284-6. doi: 10.1126/science.108.2802.284

- Salam RA, Zuberi NF, Bhutta ZA. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation during pregnancy or labour for maternal and neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jun 3;(6):CD000179. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000179.pub3

- Riikonen R, Mankinen K, Gaily E. Long-term outcome in pyridoxine-responsive infantile epilepsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2015 Nov;19(6):647-51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.08.001

- GEORGE W. FRIMPTER, ROBERT J. ANDELMAN, WALTER F. GEORGE, Vitamin B6-Dependency Syndromes: New Horizons in Nutrition, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 22, Issue 6, June 1969, Pages 794–805, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/22.6.794

- Bender, D. (1999). Non-nutritional uses of vitamin B6. British Journal of Nutrition, 81(1), 7-20. doi:10.1017/S0007114599000082

- Bendich A, Cohen M. Vitamin B6 safety issues. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;585:321-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb28064.x

- Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Vitamin B6 and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-analysis of Prospective Studies. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1077–1083. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.263

- Tryfiates GP. Effects of pyridoxine on serum protein expression in hepatoma-bearing rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981 Feb;66(2):339-44.

- Simpson JL, Bailey LB, Pietrzik K, Shane B, Holzgreve W. Micronutrients and women of reproductive potential: required dietary intake and consequences of dietary deficiency or excess. Part I–Folate, Vitamin B12, Vitamin B6. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010 Dec;23(12):1323-43. doi: 10.3109/14767051003678234

- di Salvo ML, Contestabile R, Safo MK. Vitamin B(6) salvage enzymes: mechanism, structure and regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011 Nov;1814(11):1597-608. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.12.006

- Leklem JE. Vitamin B6. In: Machlin L, ed. Handbook of Vitamins. New York: Marcel Decker Inc; 1991:341-378.

- Niebyl JR. Clinical practice. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 14;363(16):1544-50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1003896. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2010 Nov 18;363(21):2078.

- Matthews A, Dowswell T, Haas DM, Doyle M, O’Mathúna DP. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD007575. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007575.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD007575

- Vutyavanich T, Wongtra-ngan S, Ruangsri R. Pyridoxine for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995 Sep;173(3 Pt 1):881-4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90359-3

- Sahakian V, Rouse D, Sipes S, Rose N, Niebyl J. Vitamin B6 is effective therapy for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Jul;78(1):33-6.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology) Practice Bulletin: nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Apr;103(4):803-14.

- Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Jones PW, Shaughn O’Brien PM. Efficacy of vitamin B-6 in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: systematic review. BMJ. 1999 May 22;318(7195):1375-81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7195.1375

- Kashanian, M., Mazinani, R., Jalalmanesh, S. and Babayanzad Ahari, S. (2007), Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) therapy for premenstrual syndrome. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 96: 43-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.09.014

- Bendich A. The potential for dietary supplements to reduce premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000 Feb;19(1):3-12. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718907

- Ebbing, M., Bønaa, K.H., Arnesen, E., Ueland, P.M., Nordrehaug, J.E., Rasmussen, K., Njølstad, I., Nilsen, D.W., Refsum, H., Tverdal, A., Vollset, S.E., Schirmer, H., Bleie, Ø., Steigen, T., Midttun, Ø., Fredriksen, Å., Pedersen, E.R. and Nygård, O. (2010), Combined analyses and extended follow-up of two randomized controlled homocysteine-lowering B-vitamin trials. Journal of Internal Medicine, 268: 367-382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02259.x

- Saposnik G, Ray JG, Sheridan P, McQueen M, Lonn E; Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation 2 Investigators. Homocysteine-lowering therapy and stroke risk, severity, and disability: additional findings from the HOPE 2 trial. Stroke. 2009 Apr;40(4):1365-72. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.529503

- Albert CM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, Zaharris E, MacFadyen J, Danielson E, Buring JE, Manson JE. Effect of folic acid and B vitamins on risk of cardiovascular events and total mortality among women at high risk for cardiovascular disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008 May 7;299(17):2027-36. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.17.2027

- Toole JF, Malinow MR, Chambless LE, Spence JD, Pettigrew LC, Howard VJ, Sides EG, Wang CH, Stampfer M. Lowering homocysteine in patients with ischemic stroke to prevent recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and death: the Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004 Feb 4;291(5):565-75. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.5.565

- Ebbing M, Bønaa KH, Nygård O, et al. Cancer Incidence and Mortality After Treatment With Folic Acid and Vitamin B12. JAMA. 2009;302(19):2119–2126. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1622

- Balk EM, Raman G, Tatsioni A, Chung M, Lau J, Rosenberg IH. Vitamin B6, B12, and Folic Acid Supplementation and Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(1):21–30. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.1.21

- Riggs KM, Spiro A 3rd, Tucker K, Rush D. Relations of vitamin B-12, vitamin B-6, folate, and homocysteine to cognitive performance in the Normative Aging Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 Mar;63(3):306-14. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.3.306

- Malouf R, Grimley Evans J. The effect of vitamin B6 on cognition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD004393. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004393

- Gariballa S, Forster S. Effects of dietary supplements on depressive symptoms in older patients: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2007 Oct;26(5):545-51. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.06.007

- Gariballa S. Testing homocysteine-induced neurotransmitter deficiency, and depression of mood hypothesis in clinical practice. Age Ageing. 2011 Nov;40(6):702-5. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr086

- Ellis J, Folkers K, Watanabe T, Kaji M, Saji S, Caldwell JW, Temple CA, Wood FS. Clinical results of a cross-over treatment with pyridoxine and placebo of the carpal tunnel syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979 Oct;32(10):2040-6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.10.2040

- Ellis JM, Kishi T, Azuma J, Folkers K. Vitamin B6 deficiency in patients with a clinical syndrome including the carpal tunnel defect. Biochemical and clinical response to therapy with pyridoxine. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1976 Apr;13(4):743-57.

- Keniston RC, Nathan PA, Leklem JE, Lockwood RS. Vitamin B6, vitamin C, and carpal tunnel syndrome. A cross-sectional study of 441 adults. J Occup Environ Med. 1997 Oct;39(10):949-59. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199710000-00007

- Aufiero E, Stitik TP, Foye PM, Chen B. Pyridoxine hydrochloride treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: a review. Nutr Rev. 2004 Mar;62(3):96-104. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00030.x

- Ryan-Harshman M, Aldoori W. Carpal tunnel syndrome and vitamin B6. Can Fam Physician. 2007 Jul;53(7):1161-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1949298

- Curhan GC, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ. Intake of vitamins B6 and C and the risk of kidney stones in women. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999 Apr;10(4):840-5. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V104840

- Taylor EN, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Dietary factors and the risk of incident kidney stones in men: new insights after 14 years of follow-up. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004 Dec;15(12):3225-32. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000146012.44570.20

- Scheinman JI, Voziyan PA, Belmont JM, Chetyrkin SV, Kim D, Hudson BG. Pyridoxamine lowers oxalate excretion and kidney crystals in experimental hyperoxaluria: a potential therapy for primary hyperoxaluria. Urol Res. 2005 Nov;33(5):368-71. doi: 10.1007/s00240-005-0493-3 Erratum in: Urol Res. 2006 Feb;34(1):67.

- Chetyrkin SV, Kim D, Belmont JM, Scheinman JI, Hudson BG, Voziyan PA. Pyridoxamine lowers kidney crystals in experimental hyperoxaluria: a potential therapy for primary hyperoxaluria. Kidney Int. 2005 Jan;67(1):53-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00054.x

- Pearl PL, Gospe SM Jr. Pyridoxine or pyridoxal-5′-phosphate for neonatal epilepsy: the distinction just got murkier. Neurology. 2014 Apr 22;82(16):1392-4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000351

- Sacharow SJ, Picker JD, Levy HL. Homocystinuria Caused by Cystathionine Beta-Synthase Deficiency. 2004 Jan 15 [Updated 2017 May 18]. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1524

- Gdynia HJ, Müller T, Sperfeld AD, Kühnlein P, Otto M, Kassubek J, Ludolph AC. Severe sensorimotor neuropathy after intake of highest dosages of vitamin B6. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008 Feb;18(2):156-8. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.09.009

- Perry TA, Weerasuriya A, Mouton PR, Holloway HW, Greig NH. Pyridoxine-induced toxicity in rats: a stereological quantification of the sensory neuropathy. Exp Neurol. 2004 Nov;190(1):133-44. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.07.013

- Tsutsumi S, Tanaka T, Gotoh K, Akaike M. Effects of pyridoxine on male fertility. J Toxicol Sci. 1995 Aug;20(3):351-65. doi: 10.2131/jts.20.351

- Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Lentino CV, Dwyer JT, Engel JS, Thomas PR, Betz JM, Sempos CT, Picciano MF. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003-2006. J Nutr. 2011 Feb;141(2):261-6. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.133025

- Hansson O, Sillanpaa M. Letter: Pyridoxine and serum concentration of phenytoin and phenobarbitone. Lancet. 1976 Jan 31;1(7953):256. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91385-4

- Marino S, Vitaliti G, Marino SD, Pavone P, Provvidenti S, Romano C, Falsaperla R. Pyridoxine Add-On Treatment for the Control of Behavioral Adverse Effects Induced by Levetiracetam in Children: A Case-Control Prospective Study. Ann Pharmacother. 2018 Jul;52(7):645-649. doi: 10.1177/1060028018759637

- Alsaadi T, El Hammasi K, Shahrour TM. Does pyridoxine control behavioral symptoms in adult patients treated with levetiracetam? Case series from UAE. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2015 Sep 27;4:94-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ebcr.2015.08.003

- BENDICH, A. and COHEN, M. (1990), Vitamin B6 Safety Issues. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 585: 321-330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb28064.x