Renal colic

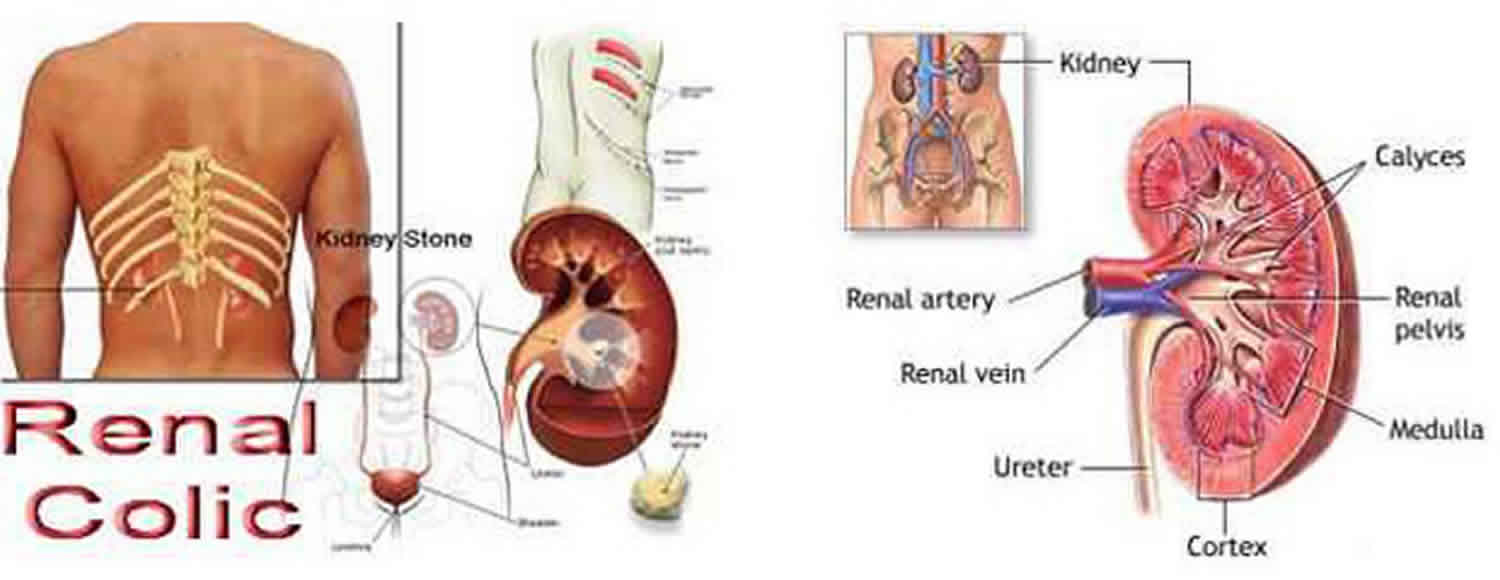

Renal colic is a type of pain commonly caused by kidney stones (nephrolithiasis) or accumulation of crystals. These kidney stones cause interference with the flow of urine and the kidney may swell up causing pain (colic). The pain of renal colic develops suddenly and is often described by patients as “the worst pain they have ever felt” 1. Renal colic pain typically begins in the kidney area or below it and radiates through the flank until it reaches the bladder. Renal colic pain is colicky in nature, meaning that it comes on in spasmodic waves as opposed to being a steady continuous pain. Renal colic may come in two varieties: dull and acute; the acute variation is particularly unpleasant and has been described as one of the strongest pain sensations felt by humans. Depending on the type and sizes of the kidney stones moving through the urinal tract the pain may be stronger in the renal or bladder area or equally strong in both.

Despite this severe presentation, the majority of urinary stones pass spontaneously 1. Therefore many patients with renal colic can be managed in primary care with a watchful waiting approach if there are no red flags present, their pain can be controlled and a prompt referral for imaging is arranged 2.

As a stone moves from the renal collecting system, it can significantly affect the genitourinary tract. A stone can cause obstruction and hydronephrosis of the ureter, decreasing the rate of ureteral peristalsis and causing urine to back up into the kidney. This can cause decreases in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of the affected kidney, and increase renal excretion of the unaffected kidney as well as very severe, excruciating pain. Complete obstruction of the ureter can lead to eventual loss of renal function, with damage becoming irreversible in one to two weeks. Additionally, there is a risk of rupture of a renal calyx with the development of a urinoma. Urinoma is a rare and unique condition that refers to extravasation of urine from a disruption of the urinary collecting system at any level from the calix to the urethra 3. Of even more concern is the possibility that an obstructed renal unit might become infected causing an obstructive pyelonephritis or pyonephrosis. This condition can be life-threatening and requires immediate surgical drainage as antibiotics alone are ineffective

Renal calculi can become impacted, most commonly at the ureteropelvic junction (the renal pelvis narrows abruptly to meet the ureter), near the pelvic brim, or at the ureterovesical junction.

Calculus size, location, and patient discomfort predict the likelihood of spontaneous stone passage. Approximately 90% of stones less than 5 mm pass within four weeks 4. Up to 95% of stones larger than 8 mm can become impacted, requiring intervention to pass 4.

Indications for hospital admission include a renal stone in a solitary kidney, severe kidney injury, an infected renal stone, intractable pain or nausea, urinary extravasation, or hypercalcemic crisis 4.

Patients with infected stones (e.g., nephrolithiasis plus evidence of urinary tract infection) require special and more urgent treatment. The infected stone acts as a nidus for infection and leads to stasis, decreasing the ability to manage infections. Frequently, these stones need to be removed in their entirety operatively to prevent a repeat infection and new stone formations.

24-hour urine tests are the cornerstone of long-term preventive therapy, but they require very high levels of patient dedication and compliance to be successful. Nevertheless, they should be offered to patients with recurrent stones and a high risk of new stone formation.

Renal colic causes

Renal colic is generally caused by stones in the upper urinary tract (urolithiasis) obstructing the flow of urine; a more clinically accurate term for the condition is therefore ureteric colic 5. The blockage in the ureter causes an increase in tension in the urinary tract wall, stimulating the synthesis of prostaglandins, causing vasodilatation 6. This leads to a diuresis which further increases pressure within the kidney. Prostaglandins also cause smooth muscle spasm of the ureter resulting in the waves of pain (colic) felt by the patient. Occasionally renal colic will occur due to a cause other than urinary stones, such as blood clots that may develop with upper urinary tract bleeding, sloughed renal papilla (e.g. due to sickle cell disease, diabetes, long-term use of analgesics) or lymphadenopathy 2.

Individual urinary stones are aggregations of crystals in a non-crystalline protein matrix 2. Eighty percent of urinary stones are reported to contain calcium, frequently in the form of calcium oxalate 2. Calcium phosphate and urate are also found in urinary stones in decreasing frequency, although urate may be more prevalent in patients who are obese 2. Bacteria can also cause the formation of calculi, referred to as infection stones, which contain magnesium ammonium phosphate and may be large and branched; these are also known as staghorn calculi 2.

Kidney stones or nephrolithiasis, is a common condition affecting 5% to 15% of the population at some point, with a yearly incidence of 0.5% in North America and Europe, and is caused by a crystal or crystalline aggregate traveling from the kidney through the genitourinary system 7. Of those, 50% will have a recurrent stone within five to seven years of initial presentation if preventive measures are not taken. Over 70% of stones occur in people 20 to 50 years old, and they are more common in men than women by a factor of about 2:1. Patients with obesity, hypertension, and/or diabetes are at increased risk for kidney stone formation 8.

There are multiple predictors and risk factors for kidney stone formation. The following are the most common 4:

- Inadequate urinary volume. Patients with low urine volumes (usually less than 1 L per day) increase the concentration of solutes (indicated by a urine with an osmolarity greater than 600 mOsm/kg) and promote urinary stasis, which can cause supersaturation of solutes and lead to stone formation.

- Hypercalciuria. Most often this is an idiopathic finding, although it can be secondary to increased intestinal absorption of calcium, increased circulating calcium, hypervitaminosis D, hyperparathyroidism, high protein load, or systemic acidosis. Hypercalciuria increases the saturation of calcium salts like oxalate and phosphate, causing the formation of crystals. Calcium containing stones form approximately 80% of all renal stones. Hypercalciuria is usually defined as urinary calcium of 250 mg or more per 24 hours.

- Elevated urine levels of uric acid (uric acid stones account for 5% to 10% of all renal calculi), oxalate, sodium urate, or cystine. Often these can be secondary to a high protein diet, high oxalate diet, or a genetic defect causing increased excretion. Most pure uric acid stones are caused by high urinary total acid levels and not by elevated urinary uric acid.

- Infection stones. These are caused by urea-splitting organisms (Proteus or Klebsiella spp but not E. coli), that break down urea in the urine, increasing concentrations of ammonia and pH which promote stone formation and growth. Also called struvite or triple phosphate (Magnesium, Ammonium, Calcium) stones.

- Inadequate urinary citrate levels. Citrate is the urinary equivalent of serum bicarbonate. It increases urinary pH, but it also acts as a specific inhibitor of crystal aggregation and stone formation. Optimal levels are approximately 250 mg/L to 300 mg/L of urine.

Renal colic symptoms

Patients with renal colic typically present with sudden onset of flank pain radiating laterally to the abdomen and/or to the groin. Patients often report a dull constant level of pain with colicky episodes of increased pain. The constant pain is often due to stretching of the renal capsule due to obstruction, whereas colicky pain can be caused by peristalsis of the genitourinary tract smooth muscle against the obstruction. Many patients report associated nausea or vomiting, and some may report gross hematuria. As the stone migrates distally and approaches the bladder, the patient may experience dysuria, urinary frequency, urgency or difficulty in urination.

Patients experiencing renal colic may present in very severe pain. Classically, these patients are unable to find a comfortable position and are often writhing on or pacing around the examination table. The exam may reveal flank pain (more commonly than abdominal pain), and the skin may be cool or sweating heavily (diaphoretic). There is often a prior personal history of stones or a family history.

Renal colic diagnosis

Diagnosis is made through a combination of history and physical exam, laboratory and imaging studies. Urinalysis shows some degree of microscopic or gross hematuria in 85% of stone patients, but should also be evaluated for signs of infection (e.g., white blood cells, bacteria). Urinary pH greater than 7.5 may be suggestive of a urease producing bacterial infection, while pH less than 5.5 may indicate the presence of uric acid calculi.

Basic metabolic panel (BMP) should be obtained to assess for renal function, dehydration, acid-base status, calcium and electrolyte balance. Complete blood count (CBC) can be considered to evaluate for white blood cell count (mild elevation is commonly secondary to white blood cell demargination) if there is a concern for infection.

Consider obtaining a parathyroid hormone (PTH) level if primary hyperparathyroidism is suspected as a cause of any hypercalcemia. If possible, urine should be strained to capture stones for analysis to help determine if there is a reversible or preventable cause of stone development. Further metabolic testing (24-hour urine collection for volume, pH, calcium, oxalate, uric acid, citrate, sodium, and potassium concentrations) should be considered in high-risk first-time stone formers, pediatric patients or recurrent stone formers. It is highly recommended in kidney stone patients with solitary kidneys, renal failure, renal transplants, gastrointestinal (GI) bypass, and any patient with high or increased anesthesia risk.

Unenhanced (or helical) CT is the gold standard of initial diagnosis, with a sensitivity of 98%, specificity of 100%, and negative predictive value of 97%. This modality allows rapid identification of a stone, provides information as to the location and size of the stone, and any associated hydroureter, hydronephrosis, or ureteral edema, and can give information regarding potential other etiologies of pain (e.g., abdominal aortic aneurysm, malignancy). In those patients with no previous history of nephrolithiasis, CT should be performed to guide management. CT scans may underestimate stone size in comparison with an intravenous pyelogram or abdominal x-ray.

However, CT scan does expose patients to a radiation burden and it can be costly. In some patients with a history of renal colic that present with pain similar to previous episodes of renal colic, it may be sufficient to perform ultrasonography. However, ultrasonography is less sensitive (60% to 76%) than CT for detecting calculi less than 5 mm, but can reliably detect hydronephrosis and evidence of obstruction (increased resistive index in the affected kidney). It is also the modality of choice for evaluating a pregnant patient with concern for renal colic. Studies have shown that using ultrasonography as a primary imaging modality does not lead to an increase in complications in comparison to CT. Ultrasound is also a good way to follow a patient known to have uric acid stones.

An abdominal x-ray also called kidney, ureter, and bladder x-ray (KUB) can identify many stones, but 10% to 20% of renal stones are radiolucent and provide little information regarding hydronephrosis, obstruction or the kidneys. Additionally, bowel gas, the bony pelvis and abdominal organs may obstruct visualization of a stone. The kidney, ureter, and bladder x-ray is recommended in kidney stone cases when the CT can is positive and the exact location of the stone is known. This helps in clearly identifying those stones that can be tracted by follow-up kidney, ureter, and bladder x-ray and those that might be amenable to lithotripsy.

Using both a kidney, ureter, and bladder x-ray and a renal ultrasonography is a reasonable alternative to a CT scan and far cheaper with less radiation exposure. Symptomatic stones are likely to produce hydronephrosis or obstruction (visible on ultrasound) or will be seen directly on the kidney, ureter, and bladder x-ray or the ultrasound.

Renal colic treatment

Renal colic is a common presentation to the emergency room, the key management principles are that of analgesia and safely excluding serious alternative diagnoses.

Renal colic treatment includes the following:

- Immediate intervention with analgesia and antiemetics. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opiates are first line therapies for analgesia. NSAIDs work in two ways in renal colic. First, NSAIDs decrease the production of arachidonic acid metabolites, which mediate pain receptors, alleviating pain caused by dissension of the renal capsule. Additionally, they cause contraction of the efferent arterioles to the glomerulus, causing a reduction in glomerular filtration, and reducing hydrostatic pressure across the glomerulus. Because patients are frequently unable to tolerate oral medications, parenteral NSAIDs like ketorolac (15 mg to 30 mg intravenously (IV) or intramuscularly (IM)) or diclofenac (37.5 mg IV) are most commonly used.

- Successful use of intravenous lidocaine for renal colic has been reported. The protocol is to inject lidocaine 120 mg in 100 mL normal saline intravenously over 10 minutes for pain management. It has been quite effective for intractable renal colic unresponsive to standard therapy and typically starts to work in 3-5 minutes. No adverse events have been reported.

- Opiate pain medication, such as morphine sulfate (0.1 mg/kg IV or IM) or hydromorphone (0.02 mg/kg IV or IM), can also be used effectively for analgesia, especially when other measures have failed. However, opiates are associated with respiratory depression and sedation, and there is a risk of dependence associated with prolonged opiate use.

- Fluid hydration. Although there is no evidence to support that empiric fluid will help “flush out” a stone, many patients are dehydrated secondary to decreased oral intake or vomiting and can benefit from hydration.

- Medical expulsive therapy. Alpha 1 adrenergic receptors exist in increasing concentration in the distal ureter. The use of alpha blockade medications (for example, tamsulosin or nifedipine) is theorized to facilitate stone passage by decreasing intra-ureteral pressure and dilating the distal ureter. However, data from randomized control trials is somewhat mixed as to whether these medications improved stone passage. The consensus opinion is they may be helpful in smaller stones in the lower or distal ureter. They are probably of little use in larger stones in the proximal ureter.

- Definitive management of impacted stones. There are several invasive methods to improve stone passage. These include shock wave lithotripsy, in which high energy shock waves are used to fragment stones, ureteroscopy with either laser or electrohydraulic stone fragmentation, or in rare cases, open surgery. In the presence of infection, a double J stent or percutaneous nephrostomy may be used to help with urinary drainage of the affected renal unit and definitive stone therapy postponed until the patient is stable.

- Behavior modification and preventative management. Increase fluid intake to optimize urine output with a goal of 2 L to 2.5 L of urine daily. Patients with calcium stones and high urine calcium concentrations should limit sodium intake and have a goal of a moderate calcium intake of 1000 mg to 1200 mg dietary calcium daily. Those with calcium stones and low urinary citrate or those with uric acid stones and high urinary uric acid should increase intake of fruits and vegetables and decrease non-dairy animal protein. They may benefit from potassium citrate supplementation. Uric Acid stone formers are usually best treated with potassium citrate (urinary alkalinizer) to a pH of 6.5. Hyperuricosuric calcium stone formers can benefit from allopurinol. Thiazide diuretics are indicated in those with high urinary calcium and recurrent calcium stones to reduce the amount of urinary calcium. Patients with hyperoxaluria should be encouraged to lower their oxalate intake (spinach, nuts, chocolate, green leafy vegetables) 9.

Surgical treatment of urinary stones

The size of the urinary stone, its position and the general health of the patient will determine which technique is the most appropriate for the removal of stones that require surgery 5. People with certain occupations, e.g. airline pilots, require complete removal of any urinary stones before they are able to return to full duties 5.

Uretero pyeloscopic laser lithotripsy uses laser pulses to break up ureteric and smaller renal stones. This has high stone-clearance rates but may cause 5:

- Infection in at least 5% of patients

- Hematuria, which will be problematic in < 1% of patients

- Postoperative pain

- Rarely, significant ureteric injury

Urinary tract infection is the only specific contraindication for this technique, and patients are able to continue to take antithrombotic medicines 5.

Shock wave lithotripsy is the least invasive but also least effective method for removing urinary stones. It is not commonly used to treat urinary stones in the ureter, but may occasionally be used to treat those in the upper ureter. The technique is generally indicated for renal stones in patients who are not troubled by pain or for patients with stones that are inaccessible via retrograde or percutaneous routes 5. Shock wave lithotripsy is less effective for stones greater than 10 – 20 mm in diameter.2 The adverse effects of shock wave lithotripsy include 5:

- Significant pain due to stone fragment passage, experienced by 15% of patients

- Hematuria is to be expected, but is problematic in less than 1% of patients

- Rarely perinephric hematoma can occur

This technique is contraindicated in patients who: are pregnant, have an active UTI (urinary tract infection), are taking antithrombotic medicines, have an aortic aneurysm or with drainage abnormalities of the kidney 5.

Percutaneous nephrolithotripsy is generally performed on renal stones larger than 20 mm and particularly staghorn calculi.2 This has an increased risk of bleeding and sepsis, compared with laser treatment, and the patient may require further treatment to remove remaining fragments.2 Patients may require several nights in hospital following this procedure 5.

Open surgery is performed rarely for patients with urinary stones that have not passed and requires an extended period in hospital and an approximate six week convalescence 5.

Preventing stone reoccurrence

Patients can take several steps to reduce the likelihood of future urinary stone formation including 5:

- Increasing water intake to dilute urine output

- Reducing salt intake

- Maintaining a healthy diet

- Avoiding fructose-containing soft drinks due to their association with increased urate levels

An analysis of stone content can guide dietary and medical interventions for urinary stone prevention. This may be useful for patients with a history of recurrent urinary stones.

Patients with stones containing calcium oxalate can be advised to reduce their salt and oxalate intake.2 Examples of foods rich in oxalate include: tea, chocolate, spinach, beetroot, rhubarb, peanuts, cola and supplementary vitamin C (most of which is converted to oxalate) 5. Patients should maintain a normal dietary calcium intake of 700 – 1000 mg per day. Potassium citrate is for patients who have had recurrent calcium oxalate urinary stones and who have had more than two episodes of urinary stones in the previous two years.

For patients with urate stones, reducing dietary purines by eating less purine-rich meat (e.g. red meat and offal) and seafood (e.g. shellfish and oily fish) is an effective way to decrease urate production 10. A urinary pH of 6.0 – 6.5 can increase the solubility of urate.

Allopurinol is indicated for the prophylaxis and treatment of patients with either urate or calcium oxalate renal stones.6 Treatment with allopurinol is recommended if urinary stones reoccur despite lifestyle modifications and adjustment of urinary pH.13 For patients without renal impairment allopurinol is initiated at 100 mg, once daily, and increased by 100 mg, every four weeks until a target serum urate of < 0.36 mmol/L is achieved. Lower doses of allopurinol are recommended for patients with estimated glomerular filtration rates < 60 mL/min/1.73 m²

If a patient is suspected of having a renal tract abnormality that may predispose them to stone formation or if a patient passes a urinary stone that when analyzed has an unusual composition, e.g. marked cystine content, then further investigations and treatment should be discussed with a urologist.

References- Holdgate A, Pollock T. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005:CD004137

- Bultitude M, Rees J. Management of renal colic. BMJ 2012;345:e5499

- B. Phillips, S. Holzmer, L. Turco et al., “Trauma to the bladder and ureter: a review of diagnosis, management, and prognosis,” European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery, vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 763–773, 2017.

- Patti L, Leslie SW. Acute Renal Colic. [Updated 2019 May 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431091

- Macneil F, Bariol S. Urinary stone disease – assessment and management. Aust Fam Physician 2011;40:772–5.

- Managing patients with renal colic in primary care: Know when to hold them. https://bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2014/April/colic.aspx

- Ganti S, Sohil P. Renal Colic: A Red Herring for Mucocele of the Appendiceal Stump. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2018;2018:2502183. Published 2018 Dec 6. doi:10.1155/2018/2502183 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6304513

- Аgenosov MP, Каgan OF, Khеyfets VK. [Features of urolithiasis in patients of advanced and senile age.] Adv Gerontol. 2018;31(3):368-373.

- Masic D, Liang E, Long C, Sterk EJ, Barbas B, Rech MA. Intravenous Lidocaine for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. Pharmacotherapy. 2018 Dec;38(12):1250-1259.

- Uric Acid Nephropathy Treatment & Management. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/244255-treatment