What is rhabdomyoma

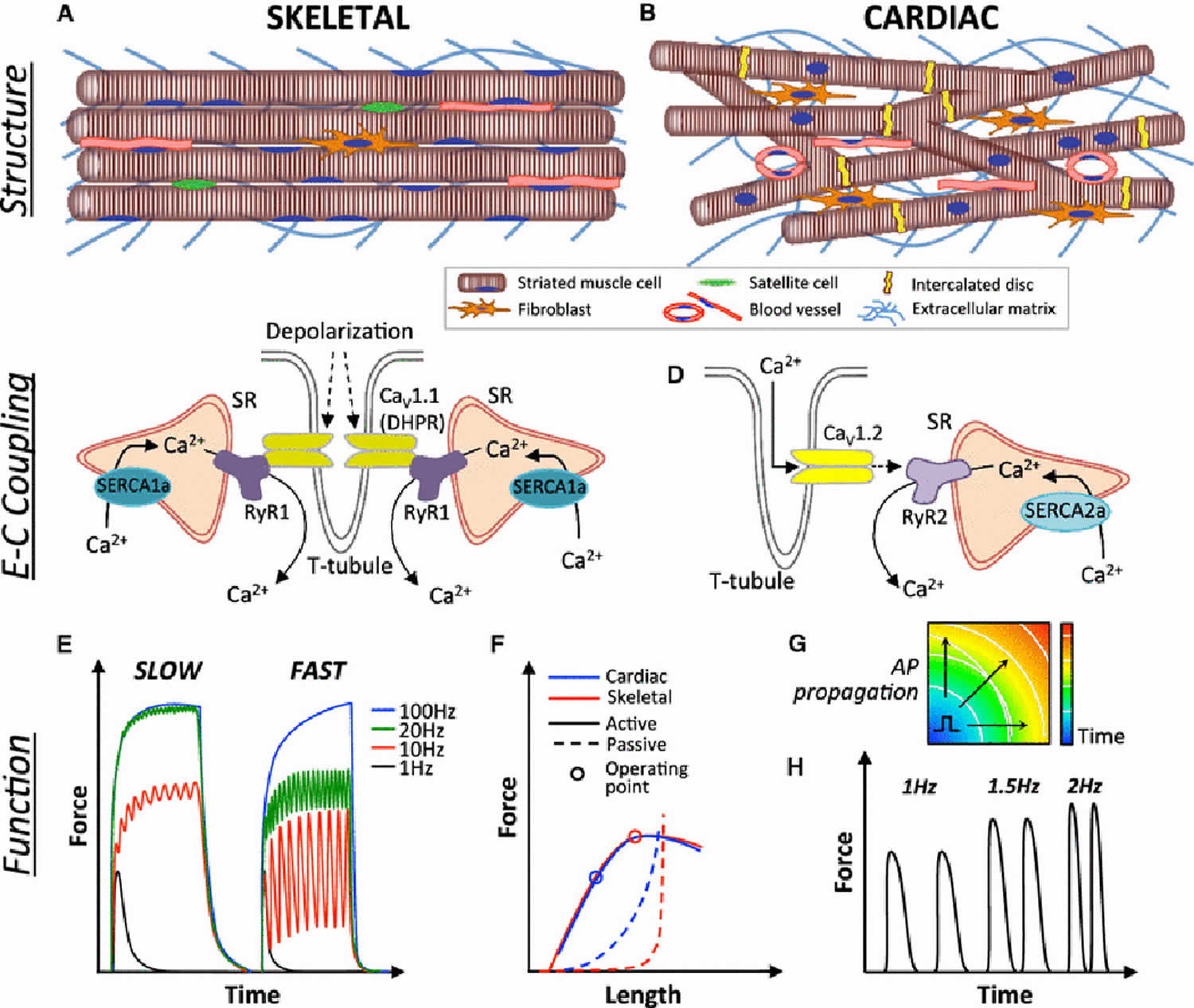

Rhabdomyoma is is an exceedingly rare benign striated muscle tumor. Striated muscles are divided into skeletal and cardiac muscle. Striated muscles are required for whole-body oxygen supply, metabolic balance, and locomotion. Striated muscles are highly organized tissues (Figure 1) that convert chemical energy to physical work. The primary function of striated muscles is to generate force and contract in order to support respiration, locomotion, and posture (skeletal muscle) and to pump blood throughout the body (cardiac muscle) 1.

Skeletal muscle also known as “voluntary muscle” that are attached by tendons to bone and is used to affect skeletal movement such as locomotion and in maintaining posture. Skeletal muscle is connected directly to the central nervous system and is under conscious control. An average adult male is made up of 40–50% of skeletal muscle and an average adult female is made up of 30–40%. Striated muscles are required for whole-body oxygen supply, metabolic balance, and locomotion.

Malignant transformation of rhabdomyomas is very rare, though there are a few case reports in the literature 2.

There are two main rhabdomyoma types, as follows:

- Neoplastic. The neoplastic variety is further divided into the following three subtypes:

- Adult

- Fetal

- Genital

- Hamartoma. Hamartoma is a benign (not cancer) growth made up of an abnormal mixture of cells and tissues normally found in the area of the body where the growth occurs. Hamartomas are divided into the following two subtypes:

- Cardiac rhabdomyoma

- Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartomas of the skin

Some investigators believe that mature striated muscle is unlikely to develop tumorous tissue. Therefore, they believe that rhabdomyoma may arise from fetal rests 2.

Rhabdomyoma is diagnosed most often in men aged 25-40 years. However, the so-called fetal rhabdomyoma chiefly affects boys between birth and age 3 years.

Most rhabdomyomas involve the head and neck regions 3. The cardiac rhabdomyoma, which is believed to be a hamartoma, usually is diagnosed in the pediatric age group. However, hamartomas are benign tumorlike growth made up of normal mature cells in abnormal number or distribution. Whereas malignant tumors contain poorly differentiated cells, hamartomas consist of distinct cell types retaining normal functions. Because their growth is limited, hamartomas are not true tumors.

Figure 1. Striated muscles

Adult rhabdomyoma

Adult rhabdomyoma is a rare tumor; very few cases have been reported in the literature 4. This tumor usually presents as a round or polypoid mass in the region of the neck. The head and neck area harbors 90% of adult rhabdomyomas and should be considered in a differential diagnosis in this region 5.

Studies in immunohistochemistry confirm that the tumors are almost totally matured neoplasms of clonal origin. Although the mass is usually asymptomatic, it may compress or displace the tongue, or it may cause partial obstruction of the pharynx. Consequently, the patient may experience some hoarseness, difficulty breathing, and difficulty swallowing.

The histopathology of adult rhabdomyoma is characterized by the presence of well-differentiated large cells that resemble striated muscle cells. Cross-striation has been demonstrated by phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin, muscle specific actin, desmin, and myoglobin; dystrophin is shown to be expressed in the cell membranes. The cells are deeply eosinophilic polygonal cells with small peripherally placed nuclei and occasional intracellular vacuoles. Adult rhabdomyoma usually is localized to the oropharynx, the larynx, and the muscles of the neck.

Fetal rhabdomyoma

Fetal rhabdomyoma occurs most often in the subcutaneous tissues of the head and neck in children between birth and age 3 years. The histopathology of fetal rhabdomyoma reveals the presence of a mixture of spindle-shaped cells with indistinct cytoplasm and muscle fibers, which resemble striated muscle tissue observed in intrauterine development at 7-12 weeks. The fetal rhabdomyoma is usually found in the subcutaneous tissues of the head and neck.

Cardiac rhabdomyoma

Cardiac rhabdomyoma is a type of benign myocardial tumor and is considered the most common fetal cardiac tumor. Cardiac rhabdomyoma has a strong association with tuberous sclerosis. Cardiac rhabdomyomas are often multiple and can represent up to 90% of cardiac tumors in the pediatric population 6. The estimated incidence is at ~1 in 20,000 births 7. Cardiac rhabdomyomas typically develop in utero and are often detected on prenatal ultrasonography. It usually involves the myocardium of both ventricles and the interventricular septum. The majority are diagnosed before the age of 1 year.

Cardiac rhabdomyoma is considered a hamartomatous lesion consisting of cardiac muscle tissue (derived from embryonal myoblasts) frequently associated with tuberous sclerosis of the brain, sebaceous adenomas, and various hamartomatous lesions of the kidney and other organs. The association of tuberous sclerosis and cardiac rhabdomyoma is important and has usually been explained by strong clinical association 8, with >50% of all cardiac rhabdomyomas found in patients with later confirmed tuberous sclerosis 9.. Molecular evidence of this association have now been identified as the TSC2 gene missense mutation (E36; 4672 G>A, 1558 E>K TSC2) 10.

The majority of cardiac rhabdomyomas are asymptomatic although there can be a broad clinical spectrum. Occasionally, they may present with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction or refractory arrhythmias.

In most cases, no treatment is required, and these lesions regress spontaneously. Patients with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction or refractory arrhythmias respond well to surgical excision. The overall prognosis is dependent on the number, size and location of the lesions as well as the presence or absence of associated anomalies.

Cardiac rhabdomyoma complications:

Patients with cardiac rhabdomyoma may develop congestive heart failure or arrhythmia.

- development of cardiac arrhythmias

- intracavitary growth may cause:

- ventricular outflow tract obstruction

- valvular compromise

- disruption of intracardiac blood flows leading to congestive heart failure and hydrops

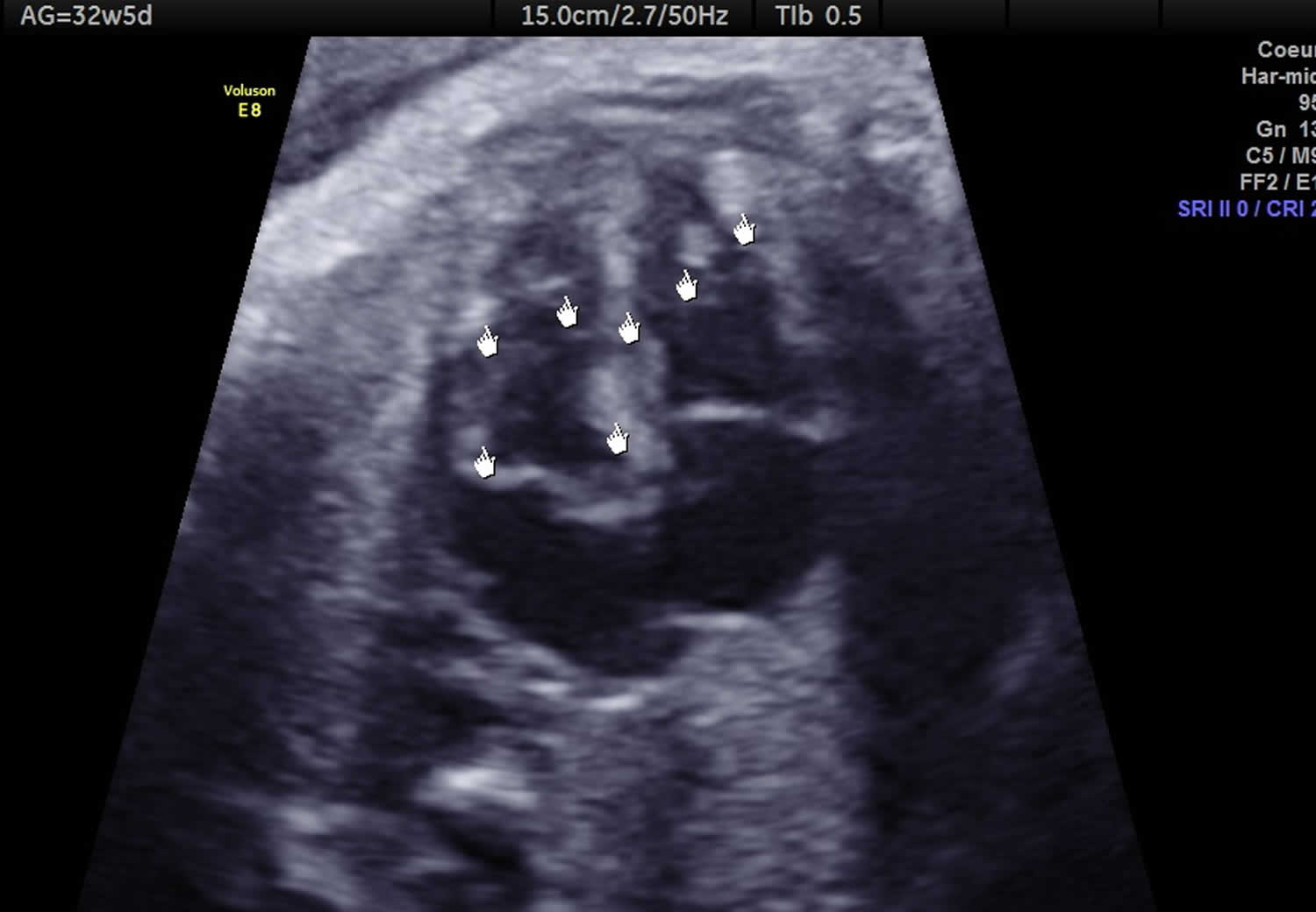

Figure 2. Cardiac rhabdomyoma ultrasound

Footnote: Multiple bright hyperechoic pseudotumoral images within the myocardium, in the interventricular septum, the right atrium and both ventricles.

[Source 11 ]Genital rhabdomyoma

Genital rhabdomyoma most often involves the vagina or vulva of young or middle-aged women 12. Most patients are asymptomatic. However, some patients have dyspareunia. The histopathology of genital rhabdomyoma reveals a mixture of fibroblastlike cells with clusters of mature cells containing distinct cross-striations and a matrix containing varying amounts of collagen and mucoid material. The genital rhabdomyoma usually presents as a polypoid or cystlike mass involving the vulva or vagina.

Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma

Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma is usually diagnosed in male and female newborns and infants. The histopathology of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of the skin reveals that the lesions are located in the subcutis and contain poorly oriented or perpendicular bundles of well-differentiated skeletal muscle with islands of fat, fibrous tissue, and occasionally proliferating nerves 13.

What cause rhabdomyoma?

Rhabdomyoma probably represents a genetic variant of striated muscle development. Drugs or environmental factors have not been identified as causes of rhabdomyoma.

Cardiac rhabdomyoma

- Cardiac rhabdomyoma is typically seen in cases of tuberous sclerosis and the pathogenesis involves mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes 14

- Mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes affect downstream molecular signalling pathways, primarily the mTOR pathway that leads to disrupted cellular growth, proliferation and motility 15

- Activation of mTOR pathway leads to increased translation and protein production by ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 (p70S6K) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), contributing to the abnormal cell growth and proliferation

- Cardiac rhabdomyoma is usually diagnosed during the second or third trimester on ultrasound, rhabdomyoma appears as round, homogeneous, hyperechogenic masses in the ventricles, and they sometimes appear as multiple foci in the ventricles and septal wall. Differential diagnosis between rhabdomyoma, fibroma or myxoma using ultrasonography for a single cardiac mass remains difficult 16

- Cells usually lose their ability to divide and undergo apoptosis via a ubiquitin-mediated pathway and regression of the hamartoma ensues 17

- Result can be complete or partial regression of hamartoma tumor.

Extracardiac rhabdomyoma

The pathogenesis of extracardiac rhabdomyoma is largely unknown, however, constitutive activation of the Hedgehog signalling (SHH pathway activation) and association with Gorlin’s syndrome have been implicated as the two key mechanisms leading to development of these soft tissue tumors 18.

Rhabdomyoma symptoms

Rhabdomyoma symptoms depend in part on the age and sex of the patient, as follows:

- Patients with adult rhabdomyoma give a history of having a mass in the region of the neck; they might experience some hoarseness, difficulty breathing, difficulty swallowing, or a combination. The physical examination of a patient with adult rhabdomyoma probably reveals the presence of a round or polypoid mass in the region of the neck.

- Patients with fetal rhabdomyoma may have a history of subcutaneous head and neck masses. Examination of the patient with fetal rhabdomyoma reveals subcutaneous masses in the head and neck regions.

- Patients with genital rhabdomyoma are young or middle-aged women who might present with a complaint of dyspareunia (persistent or recurrent genital pain that occurs just before, during or after intercourse). Examination of women with genital rhabdomyoma reveals vaginal masses.

- Patients with cardiac rhabdomyoma may present with a history of shortness of breath, sometimes associated with signs and symptoms suggestive of cerebral palsy (suggesting the possibility of associated tuberous sclerosis). Patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas may present with heart murmurs. If tuberous sclerosis is associated, the patient displays cerebral palsy–type signs. Renal functions may be altered.

Rhabdomyoma diagnosis

When rhabdomyoma is suspected, a biopsy of the lesion is indicated. Any masses, such as those found in the head and neck of patients with adult rhabdomyoma, should be biopsied to establish a diagnosis. A needle biopsy can be performed with a Tru-Cut needle. A small stab wound is made directly over the mass. The needle is introduced into the tumor, then withdrawn with a small amount of tumor tissue attached. Subsequently, a dressing is applied to the wound. The histopathologic findings from patients with adult rhabdomyoma are characterized by the presence of well-differentiated large cells, which resemble striated muscle cells. The cells are deeply eosinophilic polygonal cells with small, peripherally placed nuclei and occasional intracellular vacuoles.

Fetal rhabdomyoma is identifiable by the presence of a mixture of spindle-shaped cells with indistinct cytoplasm and muscle fibers, which resemble striated muscle tissue seen in intrauterine development at 7-12 weeks.

Genital rhabdomyoma is made up of a mixture of fibroblastlike cells with clusters of mature cells containing distinct cross-striations and a matrix containing varying amounts of collagen and mucoid material.

Cardiac rhabdomyoma consists of cells that closely resemble embryonic cardiac muscle cells.

The histopathology of rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of the skin reveals that the lesions contain poorly oriented or perpendicular bundles of well-differentiated skeletal muscle with islands of fat, fibrous tissue, and occasionally proliferating nerves.

Imaging studies

- Routine radiographic studies, including radiographs of the chest and affected areas of the body.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the affected area might be useful.

Occasionally, computed tomography (CT), particularly of the chest in cases of cardiac rhabdomyoma, might be of value.

Rhabdomyoma staging

Rhabdomyomas may be characterized on the basis of grade (G), site (T), and metastasis (M), as follows:

- G0 – Benign

- T0 – Intracapsular

- T1 – Extracapsular, intracompartmental

- M0 – None

Rhabdomyoma staging is as follows:

- Benign stage 1, latent (G0T0M0) – Remains static or heals spontaneously

- Benign stage 2, active (G0T0M0) – Progressive growth but limited by natural barriers

- Benign stage 3, aggressive (G0T1M0) – Progressive growth not limited by natural barriers

Rhabdomyoma treatment

- Patients with adult rhabdomyomas should be cared for in consultation with ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialists.

- Patients with genital rhabdomyoma should be cared for in consultation with gynecologists and urologists.

- Patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas should be cared for by cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons.

Adult rhabdomyoma may experience progressive difficulties in breathing and swallowing. In such instances, nasal oxygen may help patients with breathing difficulties. If airway obstruction is diagnosed, surgical intervention should be considered. In circumstances in which swallowing is extremely difficult, supplemental intravenous fluids may be administered until surgery is performed.

Patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas should be under the care of a cardiologist. Patients with advanced cardiac rhabdomyomas should be placed in a cardiac care unit. Anecdotal case reports show significant regression of a cardiac rhabdomyoma after receiving everolimus, an mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitor 19.

Patients with genital rhabdomyomas may require catheterization if they have symptoms of urinary tract obstruction. Patients with genital rhabdomyomas who become pregnant need to be monitored closely. They may require a cesarean delivery.

Studies have explored the expression of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and insulinlike growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) as potential therapeutic targets in rhabdomyosarcoma. In one study, IGF-1R and ALK expression was observed in 72% and 92% of alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas and 61% and 39% of embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas, respectively 20. Coexpression was observed in 68% of alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas and 32% of embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas. Combined inhibition reveals synergistic cytotoxic effects and continues to be a promising area for future study; further investigation is needed.

Patients with adult rhabdomyoma and problems related to swallowing may need to be placed on a liquid diet.

Patients with adult rhabdomyoma who are experiencing breathing difficulties should restrict their activities until appropriate treatment can be undertaken. Patients with cardiac rhabdomyoma also must restrict their activities.

Surgery

Patients with adult rhabdomyoma should be treated with surgical resection of head and neck lesions, especially those lesions that compress or displace the tongue and those that may protrude and partially obstruct the pharynx or larynx 21.

Fetal rhabdomyomas are usually located in the subcutaneous tissues. In most instances, they can be excised from various parts of the body without much difficulty.

Local excision is the treatment of choice for genital rhabdomyomas.

Open heart surgery may be necessary for the treatment of cardiac rhabdomyomas.

Rhabdomyoma prognosis

The prognosis for patients who have undergone surgery for the removal of rhabdomyomas ranges from fair to good, depending on the part of the body involved. Patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas have the highest risk.

The morbidity of rhabdomyoma depends mainly on the size, location, number of the lesions, associated anomalies such as tuberous sclerosis.

Rhabdomyoma is a benign tumor of striated muscle. Metastases have not been associated with rhabdomyoma.

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are associated with the potential for flow abnormalities if they grow to sufficient size to restrict the left ventricular outflow tract. Although many are asymptomatic, some affected patients become symptomatic in the perinatal period. The types of clinical manifestations were illustrated in a report that included 15 children with cardiac rhabdomyoma (12 with tuberous sclerosis): the clinical presentation consisted of heart failure or a cardiac murmur in six patients each and arrhythmia in three patients 22.

Based on clinical and molecular evidence, the diagnosis of fetal cardiac rhabdomyoma should lead to the careful evaluation of other fetal structures, including brain and renal parenchyma, to search for signs of tuberous sclerosis.

References- Shadrin IY, Khodabukus A, Bursac N. Striated muscle function, regeneration, and repair. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(22):4175–4202. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2285-z https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5056123

- Rhabdomyomas. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/281592-overview

- Hansen T, Katenkamp D. Rhabdomyoma of the head and neck: morphology and differential diagnosis. Virchows Arch. 2005 Nov. 447 (5):849-54.

- Dau M, Kraeft SK, Kämmerer PW. Unique manifestation of a multifocal adult rhabdomyoma involving the soft palate-case report and review of literature. J Surg Case Rep. 2019 Apr. 2019 (4):rjz116.

- Bjørndal Sørensen K, Godballe C, Ostergaard B, Krogdahl A. Adult extracardiac rhabdomyoma: light and immunohistochemical studies of two cases in the parapharyngeal space. Head Neck. 2006 Mar. 28 (3):275-9.

- Grebenc ML, Rosado de christenson ML, Burke AP et-al. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 20 (4): 1073-103.

- Entezami M, Albig M, Knoll U et-al. Ultrasound Diagnosis of Fetal Anomalies. Thieme. (2003) ISBN:1588902129.

- Shen Q, Shen J, Qiao Z, Yao Q, Huang G, Hu X. Cardiac rhabdomyomas associated with tuberous sclerosis complex in children. From presentation to outcome. Herz. 2015 Jun. 40 (4):675-8.

- The radiological appearances of tuberous sclerosis. Br J Radiol. 2000 Jan;73(865):91-8. Br J Radiol. 2000 Jan;73(865):91-8.

- Jóźwiak S, Domańska-Pakieła D, Kwiatkowski DJ, Kotulska K. Multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas as a sole symptom of tuberous sclerosis complex: case report with molecular confirmation. J Child Neurol. 2005 Dec. 20 (12):988-9.

- Cardiac rhabdomyomas in tuberous sclerosis – prenatal and neonatal findings. https://radiopaedia.org/cases/cardiac-rhabdomyomas-in-tuberous-sclerosis-prenatal-and-neonatal-findings-1?lang=us

- Iversen UM. Two cases of benign vaginal rhabdomyoma. Case reports. APMIS. 1996 Jul-Aug. 104 (7-8):575-8.

- Ashfaq R, Timmons CF. Rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartoma of skin. Pediatr Pathol. 1992 Sep-Oct. 12 (5):731-5.

- Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors 6th Edition. https://www.elsevier.com/books/enzinger-and-weisss-soft-tissue-tumors/goldblum/978-0-323-08834-3

- Krueger DA, Northrup H (October 2013). “Tuberous sclerosis complex surveillance and management: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference”. Pediatr. Neurol. 49 (4): 255–65. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.002

- Sharma N, Sharma S, Thiek JL, Ahanthem SS, Kalita A, Lynser D. Maternal and Fetal Tuberous Sclerosis: Do We Know Enough as an Obstetrician?. J Reprod Infertil. 2017;18(2):257–260. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5565905

- Wu SS, Collins MH, de Chadarévian JP (2002). “Study of the regression process in cardiac rhabdomyomas”. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 5 (1): 29–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11815866

- Hettmer S, Teot LA, Kozakewich H, et al. Myogenic tumors in nevoid Basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;37(2):147–149. doi:10.1097/MPH.0000000000000115 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4127382

- Dhulipudi B, Bhakru S, Rajan S, Doraiswamy V, Koneti NR. Symptomatic improvement using everolimus in infants with cardiac rhabdomyoma. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2019 Jan-Apr. 12 (1):45-48.

- van Gaal JC, Roeffen MH, Flucke UE, van der Laak JA, van der Heijden G, de Bont ES, et al. Simultaneous targeting of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and anaplastic lymphoma kinase in embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: a rational choice. Eur J Cancer. 2013 Nov. 49 (16):3462-70.

- Han X, Song H, Zhou L, Jiang C. Surgical resection of right ventricular rhabdomyoma under the guidance of transesophageal echocardiography on a beating heart. J Thorac Dis. 2017 Mar. 9 (3):E215-E218.

- Webb DW, Thomas RD, Osborne JP. Cardiac rhabdomyomas and their association with tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dis Child. 1993 Mar. 68 (3):367-70.