What is schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis, also known as Bilharzia, is an infection caused by a parasitic worm that lives in fresh water in subtropical and tropical regions. Schistosomiasis is second only to malaria as the most devastating parasitic disease. The parasites that cause schistosomiasis live in certain types of freshwater snails. The infectious form, known as cercariae, emerge from the snail and then contaminate the water. People become infected when their skin comes into contact with the contaminated freshwater. Most human infections are caused by Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma haematobium, or Schistosoma japonicum.

Although the worms that cause schistosomiasis are not found in the United States, more than 200 million people are infected worldwide 1. Schistosomiasis parasite is most commonly found throughout Africa, but also lives in parts of South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East and Asia.

Freshwater becomes contaminated by Schistosoma eggs when infected people urinate or defecate in the water. The eggs hatch, and if certain types of freshwater snails are present in the water, the parasites develop and multiply inside the snails. The parasite leaves the snail and enters the water where it can survive for about 48 hours. Schistosoma parasites can penetrate the skin of persons who are wading, swimming, bathing, or washing in contaminated water. Within several weeks, parasite mature into adult worms, residing in the blood vessels of the body where the females produce eggs. Some of the eggs travel to the bladder or intestine and are passed into the urine or stool.

You often don’t have any symptoms when you first become infected with schistosomiasis, but the parasite can remain in your body for many years and cause damage to organs such as the bladder, kidneys and liver.

The infection can be easily treated with a short course of medicine, so see your doctor if you think you might have schistosomiasis. Safe and effective medication is available for treatment of both urinary and intestinal schistosomiasis. Praziquantel, a prescription medication, is taken for 1-2 days to treat infections caused by all Schistosoma species.

Figure 1. Schistosoma mansoni

Figure 2. Schistosoma japonicum

Figure 3. Schistosoma haematobium

Geographic distribution

- Schistosoma mansoni is found in parts of South America and the Caribbean, Africa, and the Middle East;

- Schistosoma haematobium in Africa and the Middle East;

- Schistosoma japonicum in the Far East;

- Schistosoma mekongi in Southeast Asia;

- Schistosoma intercalatum in central West Africa.

Figure 4. Schistosomiasis geographic distribution

[Source 2] [Source 3]Schistosomiasis transmission

The worms that cause schistosomiasis live in fresh water, such as:

- ponds

- lakes

- rivers

- reservoirs

- canals

Showers that take unfiltered water directly from lakes or rivers may also spread the infection, but the worms aren’t found in the sea, chlorinated swimming pools or properly treated water supplies.

You can become infected if you come into contact with contaminated water in which certain types of snails that carry schistosomes are living – for example, when paddling, swimming or washing – and the tiny worms burrow into your skin. Once in your body, the worms move through your blood to areas such as the liver and bowel.

After a few weeks, the worms start to lay eggs. Some eggs remain inside the body and are attacked by the immune system, while some are passed out in the person’s urine or poo. Without treatment, the worms can keep laying eggs for several years.

If the eggs pass out of the body into water, they release tiny larvae that need to grow inside freshwater snails for a few weeks before they’re able to infect another person. This means it’s not possible to catch the infection from someone else who has it.

Human contact with water is thus necessary for infection by schistosomes. Various animals, such as dogs, cats, rodents, pigs, horse and goats, serve as reservoirs for Schistosoma japonicum, and dogs for Schistosoma mekongi.

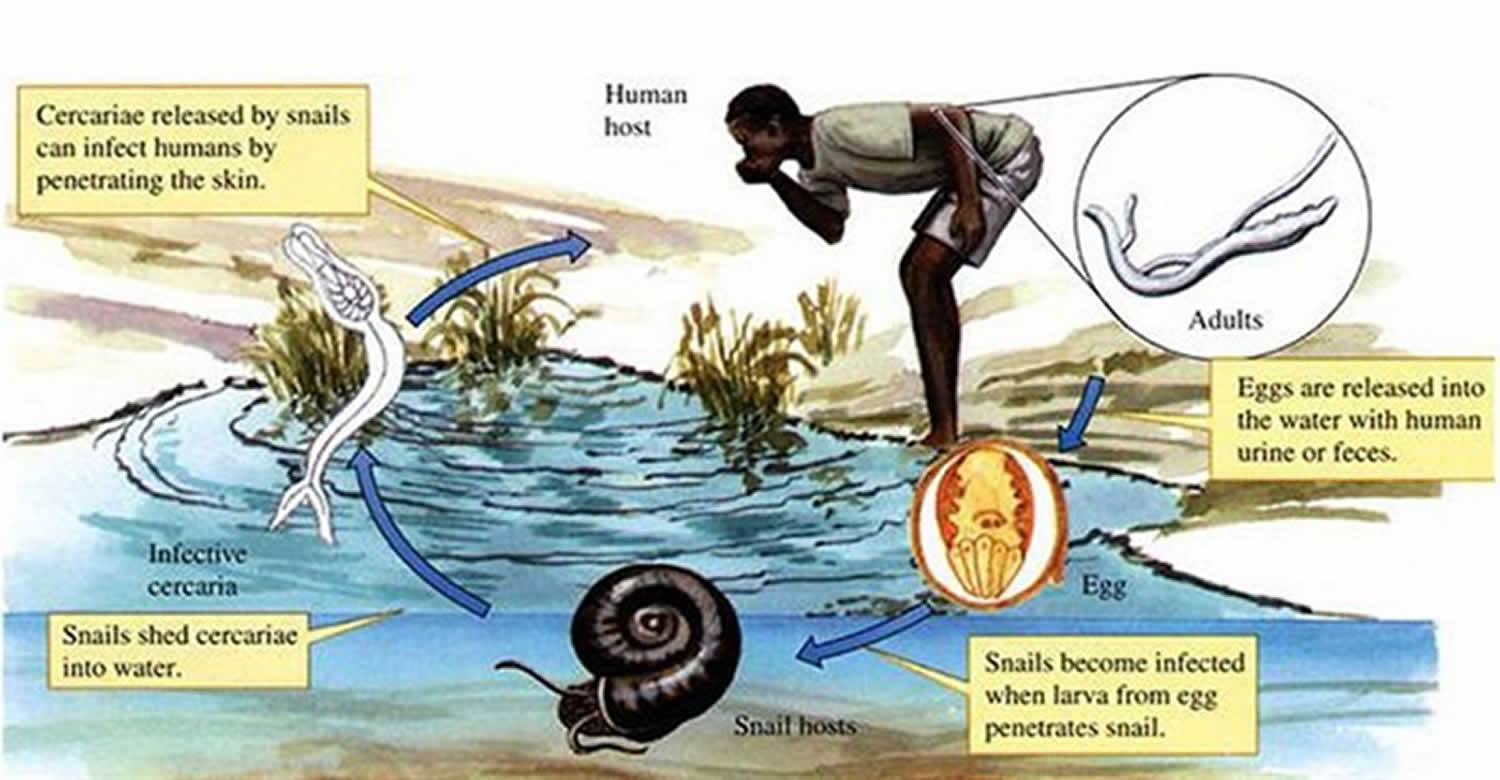

Schistosomiasis life cycle

Schistosomiasis is caused by digenetic blood trematodes. The three main species infecting humans are Schistosoma haematobium, Schistosoma japonicum, and Schistosoma mansoni. Two other species, more localized geographically, are Schistosoma mekongi and Schistosoma intercalatum. In addition, other species of schistosomes, which parasitize birds and mammals, can cause cercarial dermatitis in humans.

Figure 5. Schistosomiasis life cycle

Eggs are eliminated with feces or urine (1). Under optimal conditions the eggs hatch and release miracidia (2), which swim and penetrate specific snail intermediate hosts (3). The stages in the snail include 2 generations of sporocysts (4) and the production of cercariae (5). Upon release from the snail, the infective cercariae swim, penetrate the skin of the human host (6), and shed their forked tail, becoming schistosomulae (7). The schistosomulae migrate through several tissues and stages to their residence in the veins (number 8 and 9). Adult worms in humans reside in the mesenteric venules in various locations, which at times seem to be specific for each species (10). For instance, Schistosoma japonicum is more frequently found in the superior mesenteric veins draining the small intestine (A), and Schistosoma mansoni occurs more often in the superior mesenteric veins draining the large intestine (B). However, both species can occupy either location, and they are capable of moving between sites, so it is not possible to state unequivocally that one species only occurs in one location. Schistosoma haematobium most often occurs in the venous plexus of bladder (C), but it can also be found in the rectal venules. The females (size 7 to 20 mm; males slightly smaller) deposit eggs in the small venules of the portal and perivesical systems. The eggs are moved progressively toward the lumen of the intestine (Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum) and of the bladder and ureters (Schistosoma haematobium), and are eliminated with feces or urine, respectively The number (1). Pathology of Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum schistosomiasis includes: Katayama fever, hepatic perisinusoidal egg granulomas, Symmers’ pipe stem periportal fibrosis, portal hypertension, and occasional embolic egg granulomas in brain or spinal cord. Pathology of Schistosoma haematobium schistosomiasis includes: hematuria, scarring, calcification, squamous cell carcinoma, and occasional embolic egg granulomas in brain or spinal cord.

Schistosomiasis prevention

There’s no vaccine for schistosomiasis, so it’s important to be aware of the risks and take precautions to avoid exposure to contaminated water.

You can check whether the area you’re visiting is known to have a problem with schistosomiasis using Travel Health Pro’s country information section (https://travelhealthpro.org.uk/countries).

If you’re visiting one of these areas:

- Avoid paddling, swimming and washing in fresh water when you are in countries in which schistosomiasis occurs – only swim in the sea or chlorinated swimming pools is safe.

- take waterproof trousers and boots with you if there’s a chance you’ll need to cross a stream or river

- Boil or filter water before drinking – as the parasites could burrow into your lips or mouth if you drink contaminated water

- Drink safe water. Although schistosomiasis is not transmitted by swallowing contaminated water, if your mouth or lips come in contact with water containing the parasites, you could become infected. Because water coming directly from canals, lakes, rivers, streams, or springs may be contaminated with a variety of infectious organisms, you should either bring your water to a rolling boil for 1 minute or filter water before drinking it. Bring your water to a rolling boil for at least 1 minute will kill any harmful parasites, bacteria, or viruses present.

- Iodine treatment alone WILL NOT GUARANTEE that water is safe and free of all parasites.

- Water used for bathing should be brought to a rolling boil for 1 minute to kill any cercariae, and then cooled before bathing to avoid scalding. Water held in a storage tank for at least 1 – 2 days should be safe for bathing.

Vigorous towel drying after an accidental, very brief water exposure may help to prevent the Schistosoma parasite from penetrating the skin. However, do not rely on vigorous towel drying alone to prevent schistosomiasis. - Avoid medicines sold locally that are advertised to treat or prevent schistosomiasis – these are often either fake, substandard, ineffective or not given at the correct dosage

- Don’t rely on assurances from hotels, tourist boards or similar that a particular stretch of water is safe – there have been reports of some organizations downplaying the risks

Applying insect repellent to your skin or quickly drying yourself with a towel after getting out of the water aren’t reliable ways of preventing infection, although it’s a good idea to dry yourself as soon as possible if you’re accidentally exposed to potentially contaminated water.

- There’s some evidence that applying insect repellent containing 50% DEET to exposed areas each night after showering kills the parasite in the skin before it moves deeper into the body.

Those who have had contact with potentially contaminated water overseas should see their health care provider after returning from travel to discuss testing.

Schistosomiasis symptoms

Many people with schistosomiasis don’t have any symptoms, or don’t experience any for several months or even years.

You probably won’t notice that you’ve been infected, although occasionally people get small, itchy red bumps on their skin for a few days where the worms burrowed in. Fever, chills, cough, and muscle aches can begin within 1-2 months of infection. Most people have no symptoms at this early phase of infection.

The incubation period for patients with acute schistosomiasis is usually 14-84 days; however, many people are asymptomatic and have subclinical disease during both acute and chronic stages of infection. Persons with acute infection (also known as Katayama syndrome) may present with rash, fever, headache, myalgia, and respiratory symptoms. Often eosinophilia is present with hepato- and/or splenomegaly.

Symptoms of schistosomiasis are caused by the body’s reaction to the eggs produced by worms, not by the worms themselves.

After a few weeks, some people develop:

- a high temperature (fever) above 38 °C (100.4 °F)

- an itchy, red, blotchy and raised rash

- a cough

- diarrhea

- muscle and joint pain

- abdominal (tummy) pain

- a general sense of feeling unwell

These symptoms, also known as acute schistosomiasis (Katayama’s syndrome) may occur weeks after the initial infection, especially by Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum. Manifestations include fever, cough, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hepatosplenomegaly, and eosinophilia. These symptoms often get better by themselves within a few weeks. But it’s still important to get treated because the parasite can remain in your body and lead to long-term problems.

When adult worms are present, the eggs that are produced usually travel to the intestine, liver or bladder, causing inflammation or scarring. Children who are repeatedly infected can develop anemia, malnutrition, and learning difficulties. After years of infection, the parasite can also damage the liver, intestine, lungs, and bladder. Rarely, eggs are found in the brain or spinal cord and can cause seizures, paralysis, or spinal cord inflammation.

Occasionally central nervous system lesions occur: cerebral granulomatous disease may be caused by ectopic Schistosoma japonicum eggs in the brain, and granulomatous lesions around ectopic eggs in the spinal cord from Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma haematobium infections may result in a transverse myelitis with flaccid paraplegia. Continuing infection may cause granulomatous reactions and fibrosis in the affected organs, which may result in manifestations that include: colonic polyposis with bloody diarrhea (Schistosoma mansoni mostly); portal hypertension with hematemesis and splenomegaly (Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma japonicum, Schistosoma mansoni); cystitis and ureteritis (Schistosoma haematobium) with hematuria, which can progress to bladder cancer; pulmonary hypertension (Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma japonicum, more rarely Schistosoma haematobium); glomerulonephritis; and central nervous system lesions.

Figure 6. Acute schistosomiasis rash

Long-term problems caused by schistosomiasis

Some people with schistosomiasis, regardless of whether they had any initial symptoms or not, eventually develop more serious problems in parts of the body the eggs have traveled to.

This is known as chronic schistosomiasis.

Clinical manifestations of chronic schistosomiasis result from host immune responses to schistosome eggs. Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum eggs most commonly lodge in the blood vessels of the liver or intestine and can cause diarrhea, constipation, and blood in the stool. Chronic inflammation can lead to bowel wall ulceration, hyperplasia, and polyposis and, with heavy infections, to liver fibrosis and portal hypertension.

Schistosoma haematobium eggs tend to lodge in the urinary tract causing damage, dysuria and hematuria. Chronic infections may increase the risk of bladder cancer. S. haematobium egg deposition has also been associated with damage to the female genital tract, causing female genital schistosomiasis that can affect the cervix, Fallopian tubes, and vagina and lead to increased susceptibility to other infections.

Central nervous system lesions have been reported, but are rare. Disease is the result of ectopic deposition of eggs in the spinal cord (Schistosoma mansoni or Schistosoma haematobium) or brain (Schistosoma japonicum) and inflammatory reactions, typically the formation of granulomas that act as space occupying lesions.

Chronic schistosomiasis can include a range of symptoms and problems, depending on the exact area that’s infected. For example, an infection in the:

- digestive system can cause anemia, abdominal pain and swelling, diarrhea and blood in your poo

- urinary system can cause irritation of the bladder (cystitis), pain when peeing, a frequent need to pee, and blood in your urine

- heart and lungs can cause a persistent cough, wheezing, shortness of breath and coughing up blood

- nervous system or brain can cause seizures (fits), headaches, weakness and numbness in your legs, and dizziness

Without treatment, affected organs can become permanently damaged.

See your doctor if you develop the symptoms above and you’ve traveled in parts of the world where schistosomiasis is found, or if you’re concerned that you may have been exposed to the parasites while traveling.

Tell your doctor about your travel history and whether you think you may have been exposed to potentially contaminated water.

If your doctor suspects schistosomiasis, they may refer you to an expert in tropical diseases. The diagnosis is usually made by testing a sample of your blood. In some cases, eggs may be seen in a sample or your urine or poop.

Schistosomiasis diagnosis

Examination of stool and/or urine for ova is the primary methods of diagnosis for suspected schistosome infections. The choice of sample to diagnose schistosomiasis depends on the species of parasite likely causing the infection. Adult stages of Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma japonicum, Schistosoma mekongi, and Schistosoma intercalatum reside in the mesenteric venous plexus of infected hosts and eggs are shed in feces; Schistosoma haematobium adult worms are found in the venous plexus of the lower urinary tract and eggs are shed in urine. The eggs tend to be passed intermittently and in small amounts and may not be detected, so it may be necessary to perform a blood (serologic) test.

Careful review of travel and residence history is critical for determining whether infection is likely and which species may be causing infection. It is important to remember that both Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma haematobium are endemic in some areas of sub-Saharan Africa; patients with freshwater exposures in those areas should have both stool and urine samples examined for eggs. Testing of stool or urine can be of limited sensitivity, particularly for travelers who may have lighter burden infections. To increase the sensitivity of stool and urine examination, three samples should be collected on different days. For Schistosoma haematobium, presence of hematuria can suggest infection but this test is more useful for population studies in Africa and is not sufficiently sensitive or specific for individual patient diagnosis. The eggs are shed intermittently and in low amounts in light-intensity infections.

Serologic testing for antischistosomal antibody is indicated for diagnosis of travelers or immigrants from endemic areas who have not been treated appropriately for schistosomiasis in the past. Commonly used serologic tests detect antibody to the adult worm. For new infections, the serum sample tested should be collected at least 6 to 8 weeks after likely infection, to allow for full development of the parasite and antibody to the adult stage. Serologic testing may not be appropriate for determination of active infection in patients who have been repeatedly infected and treated in the past because specific antibody can persist despite cure. In these patients, serologic testing cannot distinguish resolved infection from active infection. An antigen test has been developed that can detect active infection based on the presence of schistosomal antigen, but this test is not commercially available in the United States and at this time is undergoing field evaluations for accurate diagnosis of low-intensity infections.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Microscopic identification of eggs in stool or urine is the most practical method for diagnosis. Stool examination should be performed when infection with Schistosoma mansoni or Schistosoma japonicum is suspected, and urine examination should be performed if Schistosoma haematobium is suspected. Eggs can be present in the stool in infections with all Schistosoma species. The examination can be performed on a simple smear (1 to 2 mg of fecal material). Since eggs may be passed intermittently or in small amounts, their detection will be enhanced by repeated examinations and/or concentration procedures (such as the formalin-ethyl acetate technique). In addition, for field surveys and investigational purposes, the egg output can be quantified by using the Kato-Katz technique (20 to 50 mg of fecal material) or the Ritchie technique. Eggs can be found in the urine in infections with S. haematobium (recommended time for collection: between noon and 3 PM) and with Schistosoma japonicum. Detection will be enhanced by centrifugation and examination of the sediment. Quantification is possible by using filtration through a Nucleopore® membrane of a standard volume of urine followed by egg counts on the membrane. Tissue biopsy (rectal biopsy for all species and biopsy of the bladder for Schistosoma haematobium) may demonstrate eggs when stool or urine examinations are negative.

Antibody detection

Antibody detection can be useful to indicate schistosome infection in patients who have traveled in schistosomiasis endemic areas and in whom eggs cannot be demonstrated in fecal or urine specimens. Test sensitivity and specificity vary widely among the many tests reported for the serologic diagnosis of schistosomiasis and are dependent on both the type of antigen preparations used (crude, purified, adult worm, egg, cercarial) and the test procedure.

At Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a combination of tests with purified adult worm antigens are used for antibody detection. All serum specimens are tested by FAST-ELISA using Schistosoma mansoni adult microsomal antigen (MAMA). A positive reaction (greater than 9 units/µl serum) indicates infection with Schistosoma species. Sensitivity for Schistosoma mansoni infection is 99%, 95% for Schistosoma haematobium infection, and <50% for Schistosoma japonicuminfection. Specificity of this assay for detecting schistosome infection is 99%. Because test sensitivity with the FAST-ELISA is reduced for species other than Schistosoma mansoni, immunoblots of the species appropriate to the patient’s travel history are also tested to ensure detection of S. haematobium and S. japonicum infections. Immunoblots with adult worm microsomal antigens are species-specific and so a positive reaction indicates the infecting species. The presence of antibody is indicative only of schistosome infection at some time and cannot be correlated with clinical status, worm burden, egg production, or prognosis. When submitting specimens, please include the patient’s travel history so the appropriate Schistosoma species will be tested by immunoblot.

Schistosomiasis treatment

Infections with all major Schistosoma species can usually be treated successfully with a short course of a medication called praziquantel, that kills the worms. Praziquantel is most effective once the worms have grown a bit, so treatment may be delayed until eight weeks after you were infected, or repeated again after this time.

The timing of treatment is important since praziquantel is most effective against the adult worm and requires the presence of a mature antibody response to the parasite. For travelers, treatment should be at least 6-8 weeks after last exposure to potentially contaminated freshwater. One study has suggested an effect of praziquantel on schistosome eggs lodged in tissues. Limited evidence of parasite resistance to praziquantel has been reported based on low cure rates in recently exposed or heavily infected populations; however, widespread clinical resistance has not occurred. Thus, praziquantel remains the drug of choice for treatment of schistosomiasis. Host immune response differences may impact individual response to treatment with praziquantel. Although a single course of treatment is usually curative, the immune response in lightly infected patients may be less robust, and repeat treatment may be needed after 2 to 4 weeks to increase effectiveness. If the pre-treatment stool or urine examination was positive for schistosome eggs, follow up examination at 1 to 2 months post-treatment is suggested to help confirm successful cure.

| Schistosoma species infection | Praziquantel dose and Duration |

|---|---|

| Schistosoma mansoni, S. haematobium, S. intercalatum | 40 mg/kg per day orally in two divided doses for one day |

| S. japonicum, S. mekongi | 60 mg/kg per day orally in three divided doses for one day |

There is a lack of safety trial data for the use of praziquantel in children less than 4 years of age or pregnant women. However, this drug has been distributed widely in mass drug administration programs and WHO now recommends that pregnant women should be treated as part of those campaigns based on extensive experience with the drug and review of the veterinary and human evidence. Similarly, WHO reports that there is growing evidence that infected children as young as 1 year old can be effectively treated with praziquantel without serious side effects; however, the drug is commonly available in the form of large, hard-to-swallow pills, which puts young children at risk for choking and other difficulties swallowing the drug.

Steroid medication can also be used to help relieve the symptoms of acute schistosomiasis, or symptoms caused by damage to the brain or nervous system.

Praziquantel Treatment in Pregnancy

Praziquantel is pregnancy category B.

- Pregnancy Category B: Either animal-reproduction studies have not demonstrated a fetal risk but there are no controlled studies in pregnant women or animal-reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect (other than a decrease in fertility) that was not confirmed in controlled studies in women in the first trimester (and there is no evidence of a risk in later trimesters).

There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. However, the available evidence suggests no difference in adverse birth outcomes in the children of women who were accidentally treated with praziquantel during mass prevention campaigns compared with those who were not. In mass prevention campaigns for which the World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk, WHO encourages the use of praziquantel in any stage of pregnancy. For individual patients in clinical settings, the risk of treatment in pregnant women who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

Treatment During Lactation

Praziquantel is excreted in low concentrations in human milk. According to WHO guidelines for mass prevention campaigns, the use of praziquantel during lactation is encouraged. For individual patients in clinical settings, praziquantel should be used in breast-feeding women only when the risk to the infant is outweighed by the risk of disease progress in the mother in the absence of treatment.

Treatment in Pediatric Patients

The safety of praziquantel in children aged less than 4 years has not been established. Many children younger than 4 years old have been treated without reported adverse effects in mass prevention campaigns and in studies of schistosomiasis. For individual patients in clinical settings, the risk of treatment of children younger than 4 years old who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

References