What is a scrotum

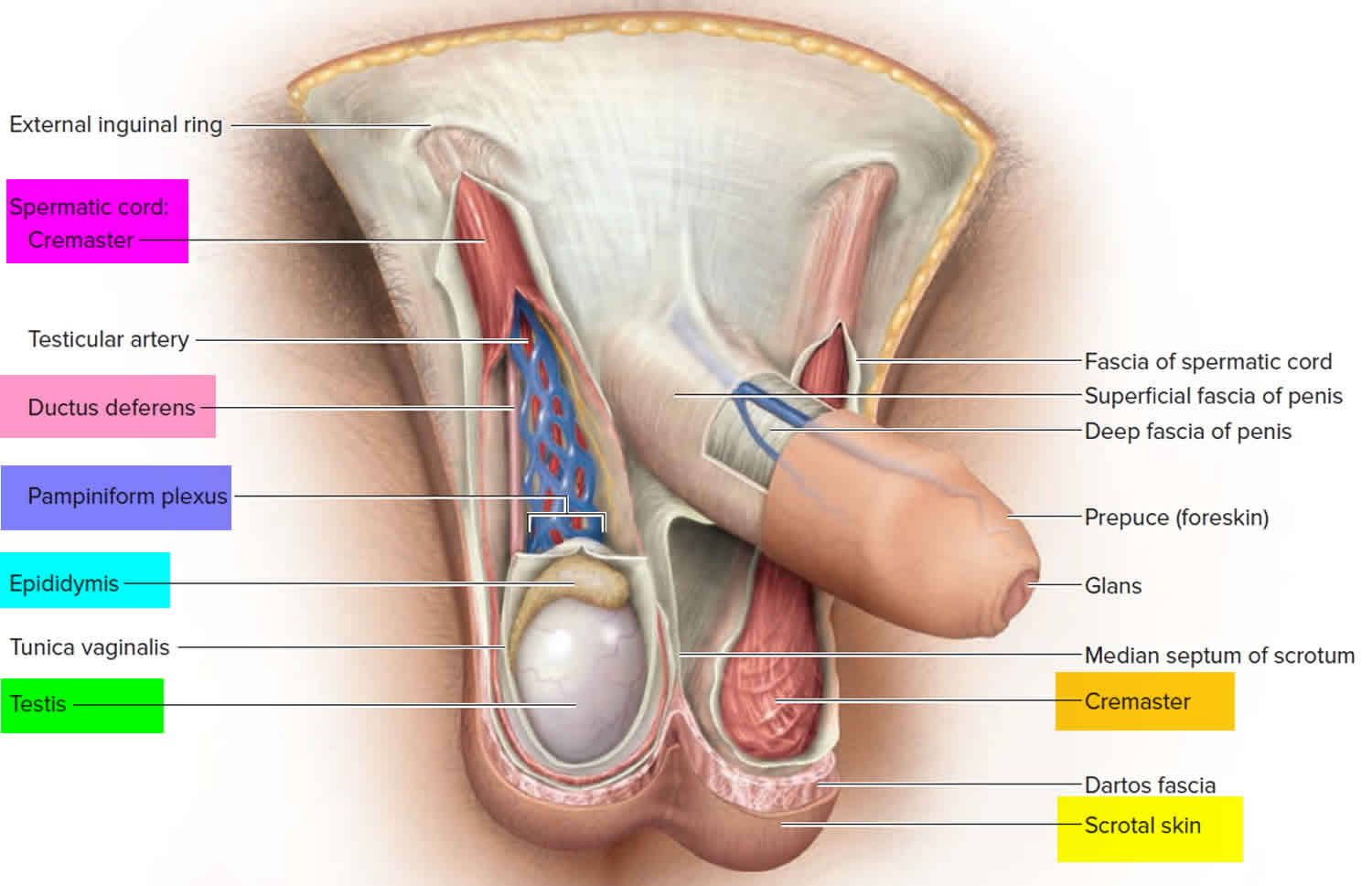

Scrotum is a loose bag of skin that hangs outside the body, behind the penis. The scrotum holds the testes in place. The scrotum is the supporting structure for the testes, consists of loose skin and underlying subcutaneous layer that hangs from the root (attached portion) of the penis (Figure 1). Externally, the scrotum looks like a single pouch of skin separated into lateral portions by a median ridge called the raphe. Internally, the scrotal septum divides the scrotum into two compartments, each containing a single testis (Figure 1). The septum is made up of a subcutaneous layer and muscle tissue called the dartos muscle, which is composed of bundles of smooth muscle fibers. The dartos muscle is also found in the subcutaneous layer of the scrotum. Associated with each testis in the scrotum is the cremaster muscle (suspender), a series of small bands of skeletal muscle that descend as an extension of the internal oblique muscle through the spermatic cord to surround the testes.

Figure 1. Scrotum anatomy

Figure 2. Testicle anatomy

Scrotum function

The scrotum surrounds the testes and controls their temperature. The location of the scrotum and the contraction of its muscle fibers regulate the temperature of the testes. Normal sperm production requires a temperature about 35.6-37.4 °F (2–3°C) below core body temperature. This lowered temperature is maintained within the scrotum because it is outside the pelvic cavity. In response to cold temperatures, the cremaster and dartos muscles contract. Contraction of the cremaster muscles moves the testes closer to the body, where they can absorb body heat. Contraction of the dartos muscle causes the scrotum to become tight (wrinkled in appearance), which reduces heat loss. Exposure to warmth reverses these actions.

Swollen scrotum symptoms

Signs and symptoms of scrotal bumps vary depending on the abnormality. Signs and symptoms might include:

- An unusual lump

- Sudden pain

- A dull aching pain or feeling of heaviness in the scrotum

- Pain that radiates throughout the groin, abdomen or lower back

- Tender, swollen or hardened testicle

- Tender, swollen or hardened epididymis, the soft, comma-shaped tube above and behind the testicle that stores and transports sperm

- Swelling in the scrotum

- Redness of the skin of the scrotum

- Nausea or vomiting

If the cause of a scrotal mass is an infection, signs and symptoms also might include:

- Fever

- Urinary frequency

- Pus or blood in the urine

What are causes of lump in scrotum

Scrotal lump is abnormal enlargement of the scrotum. Scrotal swelling can occur in males at any age. The swelling can be on one or both sides, and there may be pain. The testicles and penis may or may not be involved.

Scrotal lumps might be an accumulation of fluids, the growth of abnormal tissue, or normal contents of the scrotum that have become swollen, inflamed or hardened.

Scrotal lumps need to be examined by a doctor, even if you’re not in pain or having other symptoms. Scrotal lumps could be cancerous or caused by another condition that affects testicular function and health.

Self-examination and regular doctor exams of the scrotum are important for prompt recognition, diagnosis and treatment of scrotal masses.

Causes of scrotal swelling include:

- Certain medical treatments

- Congestive heart failure

- Epididymitis

- Hydrocele

- Inguinal hernia

- Injury

- Orchitis

- Spermatocele

- Surgery in the genital area

- Testicular torsion

- Varicocele

- Testicular cancer

- Fluid retention

It’s important for you to conduct scrotal self-exams at least monthly to detect changes, such as masses, in your scrotum. Any new mass in your scrotum should be evaluated promptly.

Your doctor can instruct you in how to conduct a testicular self-examination, which can improve your chances of finding a mass.

How to examine your testicles

A good time to examine your testicles is during or after a warm bath or shower. The heat from the water relaxes your scrotum, making it easier for you to detect anything unusual. Then follow these steps:

- Stand in front of a mirror. Look for any swelling on the skin of the scrotum.

- Examine each testicle with both hands. Place the index and middle fingers under the testicle while placing your thumbs on the top.

- Gently roll the testicle between the thumbs and the fingers. Remember that the testicles are usually smooth, oval shaped and somewhat firm. It’s normal for one testicle to be slightly larger than the other. Also, the cord leading upward from the top of the testicle (epididymis) is a normal part of the scrotum.

By regularly performing this exam, you’ll become more familiar with your testicles and aware of any changes that might be of concern. If you find a lump, call your doctor as soon as possible.

Regular self-examination is an important health habit. But it can’t substitute for a doctor’s examination. Your doctor normally checks your testicles whenever you have a physical exam.

Epididymitis

This is inflammation of the epididymis, the structure above and behind the testicle that stores and transports sperm. Epididymitis is often caused by a bacterial infection, including sexually transmitted bacterial infections, such as chlamydia. Less commonly, epididymitis is caused by a viral infection or an abnormal flow of urine into the epididymis. In men less than 35 years old, epididymitis is most commonly associated with sexually transmitted organisms such as Chlamydia trachomatis and, less commonly, Neisseria gonorrhea. Men older than 35 years or those without sexual partners usually present with gram-negative urinary pathogens which are also responsible for cystitis and prostatitis, predominantly Escherichia coli. Other urinary pathogens such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, and Ureaplasma urealyticum may be seen. Rare organisms can occur such as cytomegalovirus, Mycobacterium, and other fungal causes may be seen in immunocompromised hosts such as those with HIV 1.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s ambulatory health care data, epididymitis accounted for 1 in 144 outpatient visits in 2002 in the United States in men aged 18 to 50 years 2. The pathophysiology involves the spread of microorganisms from the urethra, prostate, or seminal vesicles, as well as hematogenous spread as in tuberculosis, causing a painful, parenchymal inflammatory process resulting in epididymal swelling. The swelling may affect the testicles, which is known as epididymo-orchitis. The common causative agents are dependent on age and sexual activity.

Sexually active men younger than 35 years are usually infected with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea, whereas older patients, patients who have undergone recent genitourinary surgery, and patients with anatomical abnormalities often have infection with gram-negative enterococci associated with urinary tract infections 3. Fungal agents such as Candida species, very rarely, can also cause epididymitis 4.

Epididymitis in the pediatric population has a peak incidence during puberty. The pathophysiology of infantile epididymitis is, in contrast to adult cases, rarely due to bacterial pathogens and remains largely unknown. Bacterial causes have been implicated in 6.2% to 9.9% of pediatric cases. Other etiologies may include anatomical abnormalities causing reflux of sterile or infected urine into the ejaculatory ducts or sequelae of a viral illness 5. It has been suggested that the association of infantile epididymitis with other urogenital abnormalities mandates further diagnostic evaluation 6. However, this recommendation remains controversial. One study assessed 49 boys for acute epididymis and found only 1 to have a relevant structural urinary tract malformation 7.

Finally, there has been an association of sterile epididymitis with the antiarrhythmic agent amiodarone in up to 11% of adult patients and rarely in children. The mechanism behind this is unknown but may be related to the accumulation of amiodarone in high concentrations in the testicular tissue 8.

Epididymitis diagnosis

Epididymitis, unlike testicular torsion, presents with gradually increasing dull, unilateral scrotal pain. Involvement of the vasa may result in exquisite pain that affects the entire hemiscrotum as well as the spermatic cord. Discerning epididymitis from torsion may be difficult; however, a history of prior genitourinary tract procedures and sexual activity are more suggestive of epididymitis 9. On physical examination, a tender and swollen epididymis and normal cremasteric reflex is observed. Urinalysis, urine cultures, and urethral cultures must be performed to identify possible causative agents. A positive urinalysis and urine cultures, along with elevated white blood cell count, favor a diagnosis of epididymitis but do not exclude torsion. Color Doppler ultrasound or nuclear scintigraphy to assess blood flow to the scrotum and its contents will help to differentiate between the two entities. Doppler ultrasound would show increased blood flow, because this is an inflammatory condition 9.

Although the incidence of tuberculous epididymitis has gradually declined in the Western hemisphere, it is important to be familiar with the typical presentation. Genital-urinary tuberculosis is the most common form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, with tuberculous epididymitis commonly being the first manifestation 10. The frequency of genital-urinary tuberculosis among those diagnosed with tuberculosis is reported to range from 2.3% to 40.9%, with tuberculous epididymitis having an incidence of 7.4% to 34.1% within this population. Tuberculous epididymitis is most common in the 35- to 55-year-old age group and can present as acute epididymitis refractory to conventional antibiotic treatment. On exam, a painful, hard, bulky mass can be appreciated. Rapid diagnosis is essential and can be made with direct examination by using auramine staining as well as genomic amplif ication polymerase chain reaction. Cultures can be concurrently taken and can be used to confirm the diagnosis and determine sensitivities for treatment 10.

Epididymitis treatment

Empiric antibiotic treatment should be started if the clinical suspicion is high. Once cultures and sensitivities are back from the lab, antibiotics should be adjusted accordingly. In the pediatric population, epididymitis should be treated with antibiotics if the urine analysis or urine culture suggests bacterial etiology; if there is no evidence of bacteria, supportive measures are suggested 11. Surgery is an option for patients with genitourinary abnormalities 5. In sexually active males younger than 35 years, empiric treatment includes ceftriaxone and doxycycline or ofloxacin. Sexual partners should also be evaluated and treated. Older patients (age greater than 35 years old) should be treated with oral levofloxacin or ofloxacin 3. Treatment also includes symptomatic relief with bed rest, scrotal elevation, analgesics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). In severe cases, a cord block may be used to alleviate pain. It is also important to discontinue or reduce the dosage of offending agents such as amiodarone for rapid resolution and avoidance of unnecessary surgical interventions in high-risk groups 12. The patient should be advised that the pain and edema usually subside in 7 to 10 days, but the epididymal induration may persist for a few weeks. If symptoms do not improve within 3 days, early follow-up is advised. Cases that persist for 6 to 8 weeks after completion of antimicrobial therapy should be reevaluated with a higher index of suspicion for unusual organisms (i.e., tuberculous or fungal etiology) 3.

Orchitis

Orchitis is swelling (inflammation) of one or both of the testicles. Bacterial or viral infections can cause orchitis, or the cause can be unknown. Orchitis is most often the result of a bacterial infection, such as a sexually transmitted infection (STI). In some cases, the mumps virus can cause orchitis.

Bacterial orchitis might be associated with epididymitis — an inflammation of the coiled tube (epididymis) at the back of the testicle that stores and carries sperm. In that case, it’s called epididymo-orchitis.

Orchitis causes pain and can affect fertility. Medication can treat the causes of bacterial orchitis and can ease some signs and symptoms of viral orchitis. But it can take several weeks for scrotal tenderness to disappear.

If you have pain or swelling in your scrotum, especially if the pain occurs suddenly, see your doctor right away.

A number of conditions can cause testicle pain, and some require immediate treatment. One such condition involves twisting of the spermatic cord (testicular torsion), which might cause pain similar to that caused by orchitis. Your doctor can perform tests to determine which condition is causing your pain.

Orchitis causes

Orchitis may be caused by an infection. Many types of bacteria and viruses can cause this condition. Sometimes a cause of orchitis can’t be determined.

The most common virus that causes orchitis is mumps. It most often occurs in boys after puberty. Orchitis most often develops 4 to 6 days after the mumps begins.

Orchitis may also occur along with infections of the prostate or epididymis.

Orchitis may be caused by an sexually transmitted infection (STI), such as gonorrhea or chlamydia. The rate of sexually transmitted orchitis or epididymitis is higher in men ages 19 to 35.

Bacterial orchitis

Most often, bacterial orchitis is associated with or the result of epididymitis. Epididymitis usually is caused by an infection of the urethra or bladder that spreads to the epididymis.

Often, the cause of the infection is an sexually transmitted infection (STI). Other causes of infection can be related to having been born with abnormalities in your urinary tract or having had a catheter or medical instruments inserted into your penis.

Viral orchitis

The mumps virus usually causes viral orchitis. Nearly one-third of males who contract the mumps after puberty develop orchitis, usually four to seven days after onset of the mumps.

Risk factors for orchitis

Risk factors for sexually transmitted orchitis include:

- High-risk sexual behaviors

- Multiple sexual partners

- Personal history of gonorrhea or another sexually transmitted infection (STI)

- Sexual partner with a diagnosed sexually transmitted infection (STI)

- Sex without a condom

- A personal history of an STI

Risk factors for orchitis not due to an STI include:

- Being older than age 45

- Long-term use of a Foley catheter

- Not being vaccinated against the mumps

- Problems of the urinary tract that were present at birth (congenital)

- Repeated urinary tract infections

- Surgery of the urinary tract (genitourinary surgery)

Orchitis prevention

To prevent orchitis:

- Get immunized against mumps, the most common cause of viral orchitis

- Practice safe sex, to help protect against STIs that can cause bacterial orchitis

Orchitis symptoms

Orchitis signs and symptoms usually develop suddenly and can include:

- Swelling in one or both testicles

- Pain in the testicle. Pain ranging from mild to severe

- Fever

- Nausea and vomiting

- General feeling of unwellness (malaise)

- Blood in the semen

- Discharge from penis

- Groin pain

- Pain with intercourse or ejaculation

- Pain with urination (dysuria)

- Scrotal swelling

- Tender, swollen groin area on affected side

- Tender, swollen, heavy feeling in the testicle

The terms “testicle pain” and “groin pain” are sometimes used interchangeably. But groin pain occurs in the fold of skin between the thigh and abdomen — not in the testicle. The causes of groin pain are different from the causes of testicle pain.

Orchitis complications

Complications of orchitis may include:

- Testicular atrophy. Orchitis can eventually cause the affected testicle to shrink. Some boys who get orchitis caused by mumps will have shrinking of the testicles (testicular atrophy).

- Scrotal abscess. The infected tissue fills with pus.

- Infertility. Occasionally, orchitis can cause infertility or inadequate testosterone production (hypogonadism). But these are less likely if orchitis affects only one testicle.

- Chronic epididymitis

- Death of testicle tissue (testicular infarction)

- Fistula on the skin of the scrotum (cutaneous scrotal fistula)

Acute pain in the scrotum or testicles can be caused by twisting of the testicular blood vessels (torsion). This is a medical emergency that requires immediate surgery.

A swollen testicle with little or no pain may be a sign of testicular cancer. If this is the case, you should have a testicular ultrasound.

Orchitis diagnosis

Your doctor is likely to start with your medical history and a physical exam to check for enlarged lymph nodes in your groin and an enlarged testicle on the affected side. Your doctor might also do a rectal examination to check for prostate enlargement or tenderness.

A physical exam may show:

- Enlarged or tender prostate gland

- Tender and enlarged lymph nodes in the groin (inguinal) area on the affected side

- Tender and enlarged testicle on the affected side

- Redness or tenderness of scrotum

Your doctor might recommend:

- Sexually transmitted infection (STI) screen. If you have discharge from your urethra, a narrow swab is inserted into the end of your penis to obtain a sample of the discharge. The sample is checked in the laboratory for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Some sexually transmitted infection (STI) screens are done with a urine test.

- Urinalysis. A sample of your urine is analyzed to see if anything’s abnormal.

- Urine culture (clean catch) — may need several samples, including initial stream, midstream, and after prostate massage

- Complete blood count (CBC).

- Ultrasound. This imaging test is the one most commonly used to assess testicular pain. Ultrasound with color Doppler can determine if the blood flow to your testicles is lower than normal — indicating torsion — or higher than normal, which helps confirm the diagnosis of orchitis.

Orchitis treatment

Treatment depends on the cause of orchitis.

Treating bacterial orchitis

Antibiotics are needed to treat bacterial orchitis and epididymo-orchitis. If the cause of the bacterial infection is an STI, your sexual partner also needs treatment.

Take the entire course of antibiotics prescribed by your doctor, even if your symptoms ease sooner, to ensure that the infection is gone.

It may take several weeks for the tenderness to disappear. Resting, supporting the scrotum with an athletic strap, applying ice packs and taking pain medication can help relieve discomfort.

Treating viral orchitis

Treatment is aimed at relieving symptoms. Your doctor might recommend:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve)

- Bed rest and elevating your scrotum

- Cold packs

Most people with viral orchitis start to feel better in three to 10 days, although it can take several weeks for the scrotal tenderness to disappear.

Orchitis prognosis

Getting the right diagnosis and treatment for orchitis caused by bacteria can most often allow the testicle to recover normally.

You will need further testing to rule out testicular cancer if the testicle does not completely return to normal after treatment.

Mumps orchitis cannot be treated, and the outcome can vary. Men who have had mumps orchitis can become sterile.

Hydrocele

A hydrocele is a fluid-filled sac in the scrotum. Hydrocele occurs when there is excess fluid between the layers of a sac that surrounds each testicle. A small amount of fluid in this space is normal, but the excess fluid of a hydrocele usually results in a painless swelling of the scrotum.

- In infants, a hydrocele occurs usually because an opening between the abdomen and the scrotum hasn’t properly sealed during development.

- In adults, a hydrocele occurs usually because of an imbalance in the production or absorption of fluid, often as a result of injury or infection in the scrotum.

Hydroceles are common in newborn infants.

During a baby’s development in the womb, the testicles descend from the abdomen through a tube into the scrotum. Hydroceles occur when this tube does not close. Fluid drains from the abdomen through the open tube and gets trapped in the scrotum. This causes the scrotum to swell.

Most hydroceles go away a few months after birth. Sometimes, a hydrocele may occur with an inguinal hernia.

Hydroceles may also be caused by:

- Buildup of the normal fluid around the testicle. This may occur because the body makes too much of the fluid or it does not drain well. (This type of hydrocele is more common in older men.)

- Swelling or injury of the testicle or epididymis

Figure 3. Hydrocele

Hydrocele symptoms

The main symptom is a painless, round-oval shaped swollen testicle, which feels like a water balloon. A hydrocele may occur on one or both sides. However, the right side is more commonly involved.

Hydrocele diagnosis

You will have a physical exam. The health care provider will find that the scrotum is swollen, but not painful to the touch. Often, the testicle cannot be felt because of the fluid around it. The size of the fluid-filled sac can sometimes be increased and decreased by putting pressure on the abdomen or the scrotum.

If the size of the fluid collection changes, it is more likely to be due to an inguinal hernia.

Hydroceles can be easily seen by shining a flashlight through the swollen part of the scrotum. If the scrotum is full of clear fluid, the scrotum will light up.

You may need an ultrasound or CT scan to confirm the diagnosis.

Hydrocele treatment

Hydroceles are not harmful most of the time. They are treated only when they cause infection or discomfort.

Hydroceles from an inguinal hernia should be fixed with surgery as soon as possible. Hydroceles that do not go away on their own after a few months may need surgery. A surgical procedure called a hydrocelectomy (removal of sac lining) is often done to correct the problem. Needle drainage does not work well because the fluid will come back.

Risks from hydrocele surgery may include:

- Blood clots

- Infection

- Injury to the scrotum

- Loss of the testicle

- Long-term (chronic) pain

- Continuous swelling

Hydrocele prognosis

Simple hydroceles in children often go away without surgery. In adults, hydroceles usually do not go away on their own. If surgery is needed, it is an easy procedure with very good outcomes.

Inguinal hernia

An inguinal hernia happens when contents of the abdomen—usually fat or part of the small intestine—bulge through a weak area in the lower abdominal wall. The abdomen is the area between the chest and the hips. The area of the lower abdominal wall is also called the inguinal or groin region.

Two types of inguinal hernias are:

- Indirect inguinal hernias, which are caused by a defect in the abdominal wall that is congenital, or present at birth

- Direct inguinal hernias, which usually occur only in male adults and are caused by a weakness in the muscles of the abdominal wall that develops over time

Inguinal hernias occur at the inguinal canal in the groin region.

Figure 4. Inguinal hernia

People who have symptoms of an incarcerated or a strangulated hernia should seek emergency medical help immediately. A strangulated hernia is a life-threatening condition.

Symptoms of an incarcerated or a strangulated hernia include:

- extreme tenderness or painful redness in the area of the bulge in the groin

- sudden pain that worsens quickly and does not go away

- the inability to have a bowel movement and pass gas

- nausea and vomiting

- fever

What is the inguinal canal?

The inguinal canal is a passage through the lower abdominal wall. People have two inguinal canals—one on each side of the lower abdomen. In males, the spermatic cords pass through the inguinal canals and connect to the testicles in the scrotum—the sac around the testicles. The spermatic cords contain blood vessels, nerves, and a duct, called the spermatic duct, that carries sperm from the testicles to the penis. In females, the round ligaments, which support the uterus, pass through the inguinal canals.

What causes inguinal hernias?

The cause of inguinal hernias depends on the type of inguinal hernia.

Indirect inguinal hernias

A defect in the abdominal wall that is present at birth causes an indirect inguinal hernia.

During the development of the fetus in the womb, the lining of the abdominal cavity forms and extends into the inguinal canal. In males, the spermatic cord and testicles descend out from inside the abdomen and through the abdominal lining to the scrotum through the inguinal canal. Next, the abdominal lining usually closes off the entrance to the inguinal canal a few weeks before or after birth. In females, the ovaries do not descend out from inside the abdomen, and the abdominal lining usually closes a couple of months before birth 13.

Sometimes the lining of the abdomen does not close as it should, leaving an opening in the abdominal wall at the upper part of the inguinal canal. Fat or part of the small intestine may slide into the inguinal canal through this opening, causing a hernia. In females, the ovaries may also slide into the inguinal canal and cause a hernia.

Indirect hernias are the most common type of inguinal hernia 14. Indirect inguinal hernias may appear in 2 to 3 percent of male children; however, they are much less common in female children, occurring in less than 1 percent 15.

Direct inguinal hernias

Direct inguinal hernias usually occur only in male adults as aging and stress or strain weaken the abdominal muscles around the inguinal canal. Previous surgery in the lower abdomen can also weaken the abdominal muscles.

Females rarely form this type of inguinal hernia. In females, the broad ligament of the uterus acts as an additional barrier behind the muscle layer of the lower abdominal wall. The broad ligament of the uterus is a sheet of tissue that supports the uterus and other reproductive organs.

Who is more likely to develop an inguinal hernia?

Males are much more likely to develop inguinal hernias than females. About 25 percent of males and about 2 percent of females will develop an inguinal hernia in their lifetimes 14. Some people who have an inguinal hernia on one side will have or will develop a hernia on the other side.

People of any age can develop inguinal hernias. Indirect hernias can appear before age 1 and often appear before age 30; however, they may appear later in life. Premature infants have a higher chance of developing an indirect inguinal hernia. Direct hernias, which usually only occur in male adults, are much more common in men older than age 40 because the muscles of the abdominal wall weaken with age 16.

People with a family history of inguinal hernias are more likely to develop inguinal hernias. Studies also suggest that people who smoke have an increased risk of inguinal hernias 17.

Inguinal hernia signs and symptoms

The first sign of an inguinal hernia is a small bulge on one or rarely, on both sides of the groin—the area just above the groin crease between the lower abdomen and the thigh. The bulge may increase in size over time and usually disappears when lying down.

Other signs and symptoms can include:

- discomfort or pain in the groin—especially when straining, lifting, coughing, or exercising—that improves when resting

- feelings such as weakness, heaviness, burning, or aching in the groin

- a swollen or an enlarged scrotum in men or boys

Indirect and direct inguinal hernias may slide in and out of the abdomen into the inguinal canal. A health care provider can often move them back into the abdomen with gentle massage.

Inguinal hernias complications

Inguinal hernias can cause the following complications:

- Incarceration. An incarcerated hernia happens when part of the fat or small intestine from inside the abdomen becomes stuck in the groin or scrotum and cannot go back into the abdomen. A health care provider is unable to massage the hernia back into the abdomen.

- Strangulation. When an incarcerated hernia is not treated, the blood supply to the small intestine may become obstructed, causing “strangulation” of the small intestine. This lack of blood supply is an emergency situation and can cause the section of the intestine to die.

Inguinal hernias treatment

Repair of an inguinal hernia via surgery is the only treatment for inguinal hernias and can prevent incarceration and strangulation. Health care providers recommend surgery for most people with inguinal hernias and especially for people with hernias that cause symptoms. Research suggests that men with hernias that cause few or no symptoms may be able to safely delay surgery until their symptoms increase 15. Men who delay surgery should watch for symptoms and see a health care provider regularly. Health care providers usually recommend surgery for infants and children to prevent incarceration 13. Emergent, or immediate, surgery is necessary for incarcerated or strangulated hernias.

A general surgeon—a doctor who specializes in abdominal surgery—performs hernia surgery at a hospital or surgery center, usually on an outpatient basis. Recovery time varies depending on the size of the hernia, the technique used, and the age and health of the person.

Hernia surgery is also called herniorrhaphy. The two main types of surgery for hernias are:

- Open hernia repair. During an open hernia repair, a health care provider usually gives a patient local anesthesia in the abdomen with sedation; however, some patients may have:

- sedation with a spinal block, in which a health care provider injects anesthetics around the nerves in the spine, making the body numb from the waist down

- general anesthesia

- The surgeon makes an incision in the groin, moves the hernia back into the abdomen, and reinforces the abdominal wall with stitches. Usually the surgeon also reinforces the weak area with a synthetic mesh or “screen” to provide additional support.

- Laparoscopic hernia repair. A surgeon performs laparoscopic hernia repair with the patient under general anesthesia. The surgeon makes several small, half-inch incisions in the lower abdomen and inserts a laparoscope—a thin tube with a tiny video camera attached. The camera sends a magnified image from inside the body to a video monitor, giving the surgeon a close-up view of the hernia and surrounding tissue. While watching the monitor, the surgeon repairs the hernia using synthetic mesh or “screen.”

People who undergo laparoscopic hernia repair generally experience a shorter recovery time than those who have an open hernia repair. However, the surgeon may determine that laparoscopy is not the best option if the hernia is large or if the person has had previous pelvic surgery.

Most adults experience discomfort and require pain medication after either an open hernia repair or a laparoscopic hernia repair. Intense activity and heavy lifting are restricted for several weeks. The surgeon will discuss when a person may safely return to work. Infants and children also experience some discomfort; however, they usually resume normal activities after several days.

Surgery to repair an inguinal hernia is quite safe, and complications are uncommon. People should contact their health care provider if any of the following symptoms appear:

- redness around or drainage from the incision

- fever

- bleeding from the incision

- pain that is not relieved by medication or pain that suddenly worsens

Possible long-term complications include:

- long-lasting pain in the groin

- recurrence of the hernia, requiring a second surgery

- damage to nerves near the hernia

Injury

Hematocele occurs where there is blood between the layers of a sac that surrounds each testicle. Traumatic injury, such as a direct blow to the testicles, is the most likely cause.

Spermatocele

A spermatocele is an abnormal sac (cyst) that develops in the epididymis — the small, coiled tube located on the upper testicle that collects and transports sperm. Also known as a spermatic cyst or epididymal cyst, spermatocele is a typically painless, noncancerous (benign), fluid-filled sac in the scrotum, usually above the testicle.

A spermatocele usually is filled with milky or clear fluid that might contain sperm.

The exact cause of spermatoceles isn’t clear, but they might be due to a blockage in one of the tubes that transport sperm.

Spermatoceles typically don’t reduce fertility or require treatment. If a spermatocele grows large enough to cause discomfort, your doctor might suggest surgery.

Figure 5. Spermatocele

Because a spermatocele usually doesn’t cause symptoms, you might discover it only during a testicular self-exam, or your doctor might find it during a routine physical exam.

It’s a good idea to have your doctor evaluate any scrotal mass to rule out a serious condition, such as testicular cancer. Also, call your doctor if you experience pain or swelling in your scrotum. A number of conditions can cause testicular pain, and some require immediate treatment.

Causes of spermatocele

The cause of spermatoceles is unknown. Spermatoceles might result from a blockage in one of the multiple tubes within the epididymis that transport and store sperm from the testicle.

Risk factors for developing a spermatocele

There aren’t many known risk factors for developing a spermatocele. Men whose mothers were given the drug diethylstilbestrol (DES) during pregnancy to prevent miscarriage and other pregnancy complications appear to have a higher risk of spermatoceles. Use of this drug was stopped in 1971 due to concerns about an increased risk of rare vaginal cancer in women.

Spermatocele symptoms

A spermatocele usually causes no signs or symptoms and might remain stable in size. If it becomes large enough, however, you might feel:

- Pain or discomfort in the affected testicle

- Heaviness in the testicle with the spermatocele

- Fullness behind and above the testicle

Spermatocele complications

A spermatocele is unlikely to cause complications.

However, if your spermatocele is painful or has grown so large that it’s causing you discomfort, you might need to have surgery to remove the spermatocele. Surgical removal might damage the epididymis or the vas deferens, a tube that transports sperm from the epididymis to the penis. Damage to either can reduce fertility. Another possible complication that can occur after surgery is that the spermatocele might come back, though this is uncommon.

Spermatocele diagnosis

To diagnose a spermatocele, you’ll need a physical exam. Although a spermatocele generally isn’t painful, you might feel discomfort when your doctor examines (palpates) the mass.

You might also undergo the following diagnostic tests:

- Transillumination. Your doctor might shine a light through your scrotum. With a spermatocele, the light will indicate that the mass is fluid-filled rather than solid.

- Ultrasound. If transillumination doesn’t clearly indicate a cyst, an ultrasound can help determine what else it might be. This test, which uses high-frequency sound waves to create images of structures, might be used to rule out a testicular tumor or other cause of scrotal swelling.

Spermatocele treatment

Although your spermatocele probably won’t go away on its own, most spermatoceles don’t need treatment. They generally don’t cause pain or complications. If yours is painful, your doctor might recommend over-the-counter pain medications, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others).

Surgical treatment

A procedure called a spermatocelectomy generally is performed on an outpatient basis, using a local or general anesthetic. The surgeon makes an incision in the scrotum and separates the spermatocele from the epididymis.

After surgery, you might need to wear a gauze-filled athletic supporter to apply pressure to and protect the site of the incision. Your doctor might also tell you to:

- Apply ice packs for two or three days to keep swelling down

- Take oral pain medications for a day or two

- Return for a follow-up exam between one and three weeks after surgery

Possible complications from surgical removal that might affect fertility include damage to the epididymis or to the tube that transports sperm (vas deferens). It’s also possible that a spermatocele might come back, even after surgery.

Aspiration, with or without sclerotherapy

Other treatments include aspiration and sclerotherapy, though these are rarely used. During aspiration, a special needle is inserted into the spermatocele and fluid is removed (aspirated).

If the spermatocele recurs, your doctor might recommend aspirating the fluid again and then injecting an irritating chemical into the sac (sclerotherapy). The irritating agent causes the spermatocele sac to scar, which takes up the space the fluid occupied and lowers the risk of the spermatocele coming back.

Damage to the epididymis is a possible complication of sclerotherapy. It’s also possible that your spermatocele might come back.

Protecting your fertility

Surgery can potentially cause damage to the epididymis or the vas deferens, and sclerotherapy might damage the epididymis, which can affect fertility. Because of this concern, these procedures might be delayed until you’re done having children. If the spermatocele is causing so much discomfort that you don’t want to wait, talk with your doctor about the risks and benefits of sperm banking.

Testicular torsion

In testicular torsion, the testicle becomes twisted in the scrotum and loses its blood supply. It is a serious emergency. If this twisting is not relieved quickly, the testicle may be permanently lost. This condition is extremely painful. Call your local emergency services number or see your health care provider immediately. Losing blood supply for just a few hours can cause tissue death and the loss of a testicle.

Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency most commonly affecting 3.8 per 100,000 males younger than 18 years (between ages 12 and 18) annually, but it can occur at any age, even before birth 18. Testicular torsion accounts for 10% to 15% of acute scrotal disease in children, and results in an orchidectomy (surgical removal of testicle) rate of 42% in boys undergoing surgery for testicular torsion. Prompt recognition and treatment are necessary for testicular salvage, and testicular torsion must be excluded in all patients who present with acute testicular pain.

Testicular torsion is a clinical diagnosis, and patients typically present with severe acute one-sided testicular pain, nausea, and vomiting 19. Physical examination may reveal a high-riding testicle with an absent cremasteric reflex. If history and physical examination suggest testicular torsion, immediate surgical exploration is indicated and should not be postponed to perform imaging studies. There is typically a four- to eight-hour window before permanent ischemic damage occurs. Delay in testicular torsion treatment may be associated with decreased fertility, or may necessitate orchiectomy (surgical removal of testicle).

Testicular torsion usually requires emergency surgery. If treated quickly, the testicle can usually be saved. But when blood flow has been cut off for too long, a testicle might become so badly damaged that it has to be removed.

The viability of the testicle in cases of torsion is difficult to predict; hence, emergent surgical treatment is indicated despite many patients presenting beyond the four- to eight-hour time frame 20. Reported testicular salvage rates are 90% to 100% if surgical exploration is performed within six hours of symptom onset, decrease to 50% if symptoms are present for more than 12 hours, and are typically less than 10% if symptom duration is 24 hours or more 21. These percentages should be considered approximate rather than absolute for the purpose of counseling patients or making clinical decisions.

Figure 6. Testicular torsion

Seek emergency care for sudden or severe testicle pain. Prompt treatment can prevent severe damage or loss of your testicle if you have testicular torsion.

You also need to seek prompt medical help if you’ve had sudden testicle pain that goes away without treatment. This can occur when a testicle twists and then untwists on its own (intermittent torsion and detorsion). Surgery is frequently needed to prevent the problem from happening again.

What causes testicular torsion

Testicular torsion occurs when the testicle rotates on the spermatic cord, which brings blood to the testicle from the abdomen. If the testicle rotates several times, blood flow to it can be entirely blocked, causing damage more quickly.

It’s not clear why testicular torsion occurs. Most males who get testicular torsion have an inherited trait that allows the testicle to rotate freely inside the scrotum. This inherited condition often affects both testicles. But not every male with the trait will have testicular torsion.

Testicular torsion often occurs several hours after vigorous activity, after a minor injury to the testicles or while sleeping. Cold temperature or rapid growth of the testicle during puberty also might play a role.

The testes develop from condensations of tissue within the urogenital ridge at approximately six weeks of gestation. With longitudinal growth of the embryo, and through endocrine and paracrine signals, which have not yet been well described, the testes ultimately descend into the scrotum by the third trimester of pregnancy. As the testes leave the abdomen, the peritoneal lining covers them, creating the processus vaginalis. The spermatic arteries and pampiniform venous plexus enter the inguinal canal proximal to the testes, and with the vas deferens, form the spermatic cord 22. The testicle is tethered to the scrotum distally by the gubernaculum.

Testicular torsion may be intravaginal or extravaginal 23. Intravaginal torsion occurs when the testicle can freely rotate within the tunica vaginalis; this can be due to a congenital anomaly called the Bell-Clapper deformity. This deformity is due to failure of posterior anchorage of the gubernaculum, epididymis, and testis, thus allowing the testis to freely rotate within the tunica vaginalis, ultimately pinching off arterial blood supply to the testicle leading to ischemia and infarction. Extravaginal torsion is seen almost exclusively in neonates, occurs when the testis rotates within the scrotum owing to inadequate fusion of the testicle to the scrotal wall via the tunica vaginalis or increased mobility of the testicle before the descent into the scrotum 24. The torsion follows rotation of the spermatic cord and results in ischemia. The degree of testicular torsion is directly correlated with the possibility of salvage after torsion and time to necrosis. The degree of torsion may be variable, usually causing venous occlusion and congestion first. Most cases of spermatic cord torsion leading to infarction are twisted at least 720 degrees. Torsion of the testicular appendages, often presenting in 7- to 13-year-old children, presents similarly to testicular torsion and accounts for 24% to 46% of acute scrotal presentations 3.

Risk factors for testicular torsion

- Age. Testicular torsion is most common between ages 12 and 18.

- Previous testicular torsion. If you’ve had testicular pain that went away without treatment (intermittent torsion and detorsion), it’s likely to occur again.

- The more frequent the bouts of pain, the higher the risk of testicular damage.

- Family history of testicular torsion. The condition can run in families.

Who’s at risk of testicular torsion

The age distribution of testicular torsion is bimodal, with one peak in the neonatal period and the second peak around puberty. In neonates, extravaginal torsion predominates, with the entire cord, including the processus vaginalis, twisting 25. Extravaginal torsion may occur antenatally or in the early postnatal period and typically presents as painless scrotal swelling, with or without acute inflammation. Testicular viability in neonatal torsion is universally poor; one literature review of 18 case series with 284 patients found a salvage rate of about 9% 26. Contralateral orchiopexy has been recommended at the time of surgical exploration because the etiology for extravaginal torsion remains unclear.12 Although no specific risk factors have been identified, poorer fixation of the neonatal tissues to one another has been implicated, and term infants with difficult or prolonged deliveries may be at higher risk 25.

In older children and adults, testicular torsion is usually intravaginal (twisting of the cord within the tunica vaginalis) 27. The Bell-clapper Deformity (Figure 4), in which there is abnormal fixation of the tunica vaginalis to the testicle, results in increased mobility of the testicle within the tunica vaginalis 28. Whether testicular torsion is intravaginal or extravaginal, twisting of the spermatic cord initially increases venous pressure and congestion, with subsequent decrease in arterial blood flow and ischemia 29. Although symptoms are typically unilateral, the anatomic conditions that predispose a persion to torsion must be presumed to be bilateral 28.

Testicular torsion prevention

Having testicles that can rotate in the scrotum is a trait inherited by some males. If you have this trait, the only way to prevent testicular torsion is surgery to attach both testicles to the inside of the scrotum.

Testicular torsion signs and symptoms

The classic presentation of testicular torsion is sudden onset of severe unilateral testicular pain associated with nausea and vomiting 30. Patients may also have nonspecific symptoms such as fever or urinary problems. Although there are no clear precipitating factors, many patients describe a recent history of trauma or strenuous physical activity 31. The ipsilateral scrotal skin may be indurated, erythematous, and warm, although changes in the overlying skin reflect the degree of inflammation and may change over time 32. A high-riding testicle can indicate a twisted, foreshortened spermatic cord 33.

The affected testicle can also have an abnormal horizontal orientation. The cremasteric reflex, which is elicited by pinching the medial thigh, causes elevation of the testicle. Presence of the reflex suggests, but does not confirm, the absence of testicular torsion 32. Comparison of the affected and unaffected sides may help delineate abnormal clinical findings, although scrotal edema and patient discomfort may limit physical examination 34. Patients in whom the components of the spermatic cord can be distinctly appreciated, whose testes are normally oriented, who have minimal to no scrotal edema, and who have no systemic symptoms (particularly with examination) are unlikely to have acute testicular torsion 32.

In cases of intermittent torsion, patients typically report recurrent episodes of acute unilateral scrotal pain 30. The pain usually resolves spontaneously within a few hours. Clinical examination and imaging are often normal if the patient presents after resolution of torsion. Chronic intermittent torsion may result in segmental ischemia of the testicle and warrants urologic evaluation 35.

Signs and symptoms of testicular torsion include:

- Sudden, severe pain in the scrotum — the loose bag of skin under your penis that contains the testicles

- Swelling of the scrotum

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- A testicle that’s positioned higher than normal or at an unusual angle

- Frequent urination

- Fever

Young boys who have testicular torsion typically wake up due to scrotal pain in the middle of the night or early in the morning.

Testicular torsion complications

Testicular torsion can cause the following complications:

- Damage to or death of the testicle. When testicular torsion is not treated for several hours, blocked blood flow can cause permanent damage to the testicle. If the testicle is badly damaged, it has to be surgically removed.

- Inability to father children. In some cases, damage or loss of a testicle affects a man’s ability to father children.

Testicular torsion diagnosis

Your doctor will ask you questions to verify whether your signs and symptoms are caused by testicular torsion or something else. Doctors often diagnose testicular torsion with a physical exam of the scrotum, testicles, abdomen and groin.

Your doctor might also test your reflexes by lightly rubbing or pinching the inside of your thigh on the affected side. Normally, this causes the testicle to contract. This reflex might not occur if you have testicular torsion.

Sometimes medical tests are necessary to confirm a diagnosis or to help identify another cause for your symptoms. For example:

- Urine test. This test is used to check for infection.

- Scrotal ultrasound. This type of ultrasound is used to check blood flow. Decreased blood flow to the testicle is a sign of testicular torsion. But ultrasound doesn’t always detect the reduced blood flow, so the test might not rule out testicular torsion.

- Surgery. Surgery might be necessary to determine whether your symptoms are caused by testicular torsion or another condition.

If you’ve had pain for several hours and your physical exam suggests testicular torsion, you might be taken directly to surgery without any additional testing. Delaying surgery might result in loss of the testicle.

Testicular torsion treatment

Manual detorsion should be attempted if surgery is not an immediate option or while preparations for surgical exploration are being made, but should not supersede or delay surgical intervention 36. Manual detorsion should not replace surgical exploration 21. The testes are typically detorsed from the medial to lateral side, turning the physician’s hands as if “opening a book” 37. Analgesic administration, intravenous sedation, or a spermatic cord block may facilitate detorsion by relaxing cremasteric fibers and controlling pain enough to allow manipulation of the testicle for detorsion. The testicle is typically twisted more than 360 degrees, so more than one rotation may be required to completely detorse the testicle 37. The subjective end point is alleviation of pain, although analgesic administration may limit the utility of this measure. Return of blood flow to the testicle on Doppler ultrasonography serves as an objective end point and should always be documented; however, relative hyperemia and altered vascular flow patterns in a newly revascularized testicle may obscure ultrasound results 21.

Testicular torsion surgery

Surgery is required to correct testicular torsion. In some instances, the doctor might be able to untwist the testicle by pushing on the scrotum (manual detorsion). But you’ll still need surgery to prevent torsion from occurring again.

Surgery for testicular torsion is usually done under general anesthesia. A transscrotal surgical approach is typically used to deliver the affected testicle into the operative field 38. Detorsion of the affected spermatic cord is performed until no twists are visible, and testicular viability has been assessed and stitch one or both testicles to the inside of the scrotum.

The sooner the testicle is untwisted, the greater the chance it can be saved. After six hours from the start of pain, the chances of needing testicle removal are greatly increased. If treatment is delayed more than 12 hours from the start of pain, there is at least a 75 percent chance of needing testicle removal.

Orchiectomy is performed if the affected testicle appears grossly necrotic or nonviable. Orchiectomy rates vary widely in the literature, typically ranging from 39% to 71% in most series 39. Age and prolonged time to definitive treatment have been identified as risk factors for orchiectomy 40. The rate of testicular loss can approach 100% in cases where the diagnosis is missed, emphasizing the necessity of maintaining a high index of suspicion for torsion in males presenting with scrotal pain 40. If the affected testicle is deemed viable, orchiopexy with permanent suture should be performed to permanently fix the testicle within the scrotum 41.

Contralateral orchiopexy should be performed regardless of the viability of the affected testicle 42. The bell-clapper deformity that increases testicular mobility and, therefore, the risk of torsion, is bilateral in up to 80% of patients 28. It is assumed to be present contralaterally in all patients with testicular torsion 43.

Testicular torsion in newborns and infants

Testicular torsion can occur in newborns and infants, though it’s rare. The infant’s testicle might be hard, swollen or a darker color. Ultrasound might not detect reduced blood flow to the infant’s scrotum, so surgery might be needed to confirm testicular torsion.

Treatment for testicular torsion in infants is controversial. If a boy is born with signs and symptoms of testicular torsion, it might be too late for emergency surgery to help and there are risks associated with general anesthesia. But emergency surgery can sometimes save all or part of the testicle and can prevent torsion in the other testicle. Treating testicular torsion in infants might prevent future problems with male hormone production and fertility.

Varicocele

Varicoceles are varicose veins or swelling of the veins inside the scrotum 44. Varicoceles form in the veins that run along the spermatic cord (the cord that holds up a man’s testicles). Blood from the testicles flows back into the body through those veins. Like varicose veins in the legs, varicoceles form when blood builds up in the veins and they become permanently enlarged.

Figure 7. Varicocele

Causes of varicocele

A varicocele forms when valves inside the veins that run along the spermatic cord prevent blood from flowing properly. Blood backs up, leading to swelling and widening of the veins. (This is similar to varicose veins in the legs.)

Most of the time, varicoceles develop slowly. They are more common in men ages 15 to 25 and are most often seen on the left side of the scrotum.

A varicocele in an older man that appears suddenly may be caused by a kidney tumor, which can block blood flow to a vein.

Varicocele symptoms

Varicocele symptoms include:

- Enlarged, twisted veins in the scrotum

- Dull ache or discomfort

- Painless testicle lump, scrotal swelling, or bulge in the scrotum

- Possible problems with fertility or decreased sperm count

Some men do not have symptoms.

Varicocele possible complications

- Infertility is a complication of varicocele.

Complications from treatment may include:

- Atrophic testis

- Blood clot formation

- Infection

- Injury to the scrotum or nearby blood vessel

Varicocele diagnosis

You will have an exam of your groin area, including the scrotum and testicles. Your health care provider may feel a twisted growth along the spermatic cord.

Sometimes the growth may not be able to be seen or felt, especially when you are lying down.

The testicle on the side of the varicocele may be smaller than the one on the other side.

You may also have an ultrasound of the scrotum and testicles, as well as an ultrasound of the kidneys.

Varicocele treatment

A jock strap or snug underwear may help ease discomfort. You may need other treatment if the pain does not go away or you develop other symptoms.

Surgery to correct a varicocele is called varicocelectomy. For this procedure:

- You will receive some type of numbing medicine (anesthesia).

- The urologist will make a cut, most often in the lower abdomen, and tie off the abnormal veins. This directs blood flow in the area to the normal veins. The operation may also be done as a laparoscopic procedure (through small incisions with a camera).

- You will be able to leave the hospital on the same day as your surgery.

- You will need to keep an ice pack on the area for the first 24 hours after surgery to reduce swelling.

An alternative to surgery is varicocele embolization. For this procedure:

- A small hollow tube called a catheter (tube) is placed into a vein in your groin or neck area.

- Your doctor moves the tube into the varicocele using x-rays as a guide.

- A tiny coil passes through the tube into the varicocele. The coil blocks blood flow to the bad vein and sends it to normal veins.

- You will need to keep an ice pack on the area to reduce swelling and wear a scrotal support for a little while.

This method is also done without an overnight hospital stay. It uses a much smaller cut than surgery, so you will heal faster.

Varicocele prognosis

A varicocele is often harmless and often does not need to be treated, unless there is a change in the size of your testicle.

If you have surgery, your sperm count will likely increase. However, it will not improve your fertility. In most cases, testicular wasting (atrophy) does not improve unless surgery is done early in adolescence.

Testicular cancer

Testicular cancer can occur in one or both of a man’s testicles. Your testicles are found in the scrotum, the skin sac that hangs beneath your penis. They can vary in size and are round, smooth, and firm. They produce male hormones and sperm.

Compared with other types of cancer, testicular cancer is rare. But testicular cancer is the most common cancer in American males between the ages of 15 and 35.

Testicular cancer facts 45

- Males of any age can develop testicular cancer, including infants and elderly men.

- About half of all cases of testicular cancer are in men between the ages of 20 and 34.

- Testicular cancer is not common; a man’s lifetime chance of getting it is about 1 in 263. The risk of dying from this cancer is about 1 in 5,000.

- Testicular cancer can be treated and usually cured, especially when it’s found early – when it’s small and hasn’t spread.

The American Cancer Society’s estimates for testicular cancer in the United States for 2018 are 46:

- About 9,310 new cases of testicular cancer diagnosed

- About 400 deaths from testicular cancer

The incidence rate of testicular cancer has been increasing in the United States and many other countries for several decades. The increase is mostly in seminomas. Experts have not been able to find reasons for this increase. Lately, the rate of increase has slowed.

Testicular cancer is not common; about 1 of every 250 males will develop testicular cancer at some point during their lifetime.

The average age at the time of diagnosis of testicular cancer is about 33. This is largely a disease of young and middle-aged men, but about 6% of cases occur in children and teens, and about 8% occur in men over the age of 55.

Because testicular cancer usually can be treated successfully, a man’s lifetime risk of dying from this cancer is very low: about 1 in 5,000.

Testicular cancer is highly treatable, even when cancer has spread beyond the testicle. Depending on the type and stage of testicular cancer, you may receive one of several treatments, or a combination.

Testicular cancer is treatable and curable. Early detection improves your outcome. You may still have children if you only have one testicle removed. The removal of both testicles means you will be infertile. You may have an option to store your sperm before treatment.

Talk to your doctor about check ups and management after treatment. They may suggest you join a support group or get counseling.

Figure 8. Testicular cancer

Note: Pain, swelling or lumps in your testicle or groin area may be a sign or symptom of testicular cancer or other medical conditions requiring treatment.

What causes testicular cancer?

It’s not clear what causes testicular cancer in most cases. Doctors know that testicular cancer occurs when healthy cells in a testicle become altered. Healthy cells grow and divide in an orderly way to keep your body functioning normally. But sometimes some cells develop abnormalities, causing this growth to get out of control — these cancer cells continue dividing even when new cells aren’t needed. The accumulating cells form a mass in the testicle.

Nearly all testicular cancers begin in the germ cells — the cells in the testicles that produce immature sperm. What causes germ cells to become abnormal and develop into cancer isn’t known.

Scientists have found that the disease is linked with a number of other conditions, which are described in the section the risk factors for testicular cancer. A great deal of research is being done to learn more about the causes.

Researchers are learning how certain changes in a cell’s DNA can cause the cell to become cancerous. DNA is the chemical in each of our cells that makes up our genes. Genes tell our cells how to function. They are packaged in chromosomes, which are long strands of DNA in each cell. Most cells in the body have 2 sets of 23 chromosomes (one set of chromosomes comes from each parent), but each sperm or egg cell has only 23 chromosomes. When the sperm and egg combine, the resulting embryo has a normal number of chromosomes in each cell, half of which are from each parent. We usually look like our parents because they are the source of our DNA. But DNA affects more than how we look.

Some genes control when our cells grow, divide into new cells, and die. Certain genes that help cells grow and divide are called oncogenes. Others that slow down cell division or make cells die at the right time are called tumor suppressor genes. Cancers can be caused by changes in chromosomes that turn on oncogenes or turn off tumor suppressor genes.

Most testicular cancer cells have extra copies of a part of chromosome 12 (called isochromosome 12p or i12p). Some testicular cancers have changes in other chromosomes as well, or even abnormal numbers of chromosomes (often too many). Scientists are studying these DNA and chromosome changes to learn more about which genes are affected and how this might lead to testicular cancer.

Risk factors for testicular cancer

Factors that may increase your risk of testicular cancer include:

- An undescended testicle (cryptorchidism). The testes form in the abdominal area during fetal development and usually descend into the scrotum before birth. Normally, the testicles develop inside the abdomen of the fetus and they go down (descend) into the scrotum before birth. In about 3% of boys, however, the testicles do not make it all the way down before the child is born. Sometimes the testicle remains in the abdomen. In other cases, the testicle starts to descend but remains stuck in the groin area. Men who have a testicle that never descended are at greater risk of testicular cancer than are men whose testicles descended normally. The risk remains elevated even if the testicle has been surgically relocated to the scrotum. Still, the majority of men who develop testicular cancer don’t have a history of undescended testicles. About 1 out of 4 cases of testicular cancer occur in the normally descended testicle. Because of this, some doctors conclude that cryptorchidism doesn’t actually cause testicular cancer but that there is something else that leads to both testicular cancer and abnormal positioning of one or both testicles.

- Abnormal testicle development. Conditions that cause testicles to develop abnormally, such as Klinefelter syndrome, may increase your risk of testicular cancer.

- Family history. If family members have had testicular cancer, you may have an increased risk. But only a small number of testicular cancers occur in families. Most men with testicular cancer do not have a family history of the disease.

- Age. Testicular cancer affects teens and younger men, particularly those between ages 15 and 35. However, it can occur at any age, including infants and elderly men.

- Race. Testicular cancer is more common in white men than in black men.

- HIV infection. Some evidence has shown that men infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), particularly those with AIDS, are at increased risk. No other infections have been shown to increase testicular cancer risk.

- Carcinoma in situ of the testicle. This condition often doesn’t cause a lump in the testicles or any other symptoms. It isn’t clear how often carcinoma in situ (CIS) in the testicles progresses to cancer. In some cases, CIS is found in men who have a testicular biopsy to evaluate infertility or have a testicle removed because of cryptorchidism. Doctors in Europe are more likely than the doctors in this country to look for CIS. This may be why the numbers for diagnosis and progression of CIS to cancer are lower in the United States than in parts of Europe. Since doctors don’t know how often CIS becomes true (invasive) cancer, it isn’t clear if treating CIS is a good idea. Some experts think that it may be better to wait and see if the disease gets worse or becomes a true cancer. This could allow many men with CIS to avoid the risks and side effects of treatment. When CIS is treated, radiation or surgery (to remove the testicle) is used.

- Having had testicular cancer before. A personal history of testicular cancer is another risk factor. About 3% or 4% of men who have been cured of cancer in one testicle will eventually develop cancer in the other testicle.

- Body size. Several studies have found that tall men have a somewhat higher risk of testicular cancer, but some other studies have not. Most studies have not found a link between testicular cancer and body weight.

Unproven or controversial risk factors

Prior injury or trauma to the testicles and recurrent actions such as horseback riding do not appear to be related to the development of testicular cancer.

Most studies have not found that strenuous physical activity increases testicular cancer risk. Being physically active has been linked with a lower risk of several other forms of cancer as well as a lower risk of many other health problems.

Can testicular cancer be prevented or avoided?

You cannot prevent or avoid testicular cancer. This type of cancer is rare, but is found more in men who are 15 to 34 years old. Other risk factors include:

- A family history of testicular cancer.

- Being of Caucasian (white) descent.

- Having an undescended testicle. This occurs when a testicle does not come down into your scrotum. The risk applies even if you have surgery to remove or

- drop the testicle.

- Having small or misshaped testicles.

- Having an HIV infection.

- Having Klinefelter syndrome. This is a rare disorder in which a man is born with an extra X chromosome.

Testicular cancer symptoms

The most common sign of testicular cancer is a hard, painless lump on your testicle. Other symptoms include:

- pain or a dull ache in your scrotum

- enlarged testicle

- swelling of your scrotum

- heavy feeling in your scrotum

- pain in your lower back or stomach

- tender or enlarged breasts.

How is testicular cancer diagnosed?

You can find cancer early by doing a testicular self-examination. Contact your doctor if you notice something unusual.

Your doctor will perform a physical exam. They will feel your scrotum and testicles for any lumps. They may do a transillumination test. This is done by shining a light up to your scrotum. If the light does not pass through a lump, it could be cancerous. Keep in mind, it is possible to have a lump, or tumor, on your testicle that is not cancer.

To confirm cancer, your doctor will need to do other tests. These may include a blood test, ultrasound, X-ray, or computed tomography (CT) scan. If you have cancer, your doctor will check to see what type and stage it is.

Seminoma is a slow-growing type of cancer. Nonseminoma cancer grows more quickly. You may have cancer that contains both cell types. Stage 1 cancer has not spread. Stage 2 has spread to your lymph nodes. Stage 3 has spread to body organs, such as your lungs, stomach, or spine.

Testicular cancer treatment

Treatment depends on the type and stage of cancer you have. Your general health is a factor, as well. Most men who have testicular cancer will require surgery. This removes the cancerous testicle.

Your doctor may recommend other treatments. This is more common if your cancer is severe, has spread, or reoccurs. Radiation therapy kills cancer cells using X-rays or radio waves. Chemotherapy kills cancer cells using powerful medicines.

References- Santi M, Lava SAG, Simonetti GD, Bianchetti MG, Milani GP. Acute Idiopathic Scrotal Edema: Systematic Literature Review. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2018 Jun;28(3):222-226.

- Trojian TH, Lishnak TS, Heiman D. Epididymitis and orchitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:583–587.

- Marcozzi D, Suner S. The nontraumatic, acute scrotum. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2001;19:547–568.

- Hori S, Tsutsumi Y. Histological differentiation between chlamydial and bacterial epididymitis: nondestructive and proliferative versus destructive and abscess forming: immunohistochemical and clinicopathological findings. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:402–407.

- Redshaw JD, Tran TL, Wallis MC, deVries CR. Epididymitis: a 21-year retrospective review of presentations to an outpatient urology clinic. J Urol. 2014;192:1203–1207.

- Hamdan M, Cerabona V. Epididymitis in infants. Apropos of a case and review of the literature. J Urol (Paris) 1991;97:228–229.

- Haecker FM, Hauri-Hohl A, von Schweinitz D. Acute epididymitis in children: a 4-year retrospective study. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2005;15:180–186.

- Cicek T, Cicek Demir C, Coban G, Coner A. Amiodarone induced epididymitis: a case report. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e13929.

- Boettcher M, Bergholz R, Krebs TF, Wenke K, Treszl A, Aronson DC, et al. Differentiation of epididymitis and appendix testis torsion by clinical and ultrasound signs in children. Urology. 2013;82:899–904.

- Gomez Garcia I, Gomez Mampaso E, Burgos Revilla J, Molina MR, Sampietro Crespo A, Buitrago LA, et al. Tuberculous orchiepididymitis during 1978-2003 period: review of 34 cases and role of 16S rRNA amplification. Urology. 2010;76:776–781.

- Joo JM, Yang SH, Kang TW, Jung JH, Kim SJ, Kim KJ. Acute epididymitis in children: the role of the urine test. Korean J Urol. 2013;54:135–138.

- Kavoussi PK, Costabile RA. Orchialgia and the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. World J Urol. 2013;31:773–778.

- Aiken JJ, Oldham KT. Chapter 38: Inguinal hernias. In: Kleigman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 1362–1368.

- Nicks BA. Hernias. Medscape website. http://emedicine.medscape.com. Updated April 21, 2014. Accessed April 23, 2014.

- Kelly KB, Ponsky TA. Pediatric abdominal wall defects. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2013;93(5):1255–1267.

- Quintas ML, Rodrigues CJ, Yoo JH, Rodrigues Junior AJ. Age related changes in the elastic fiber system of the interfoveolar ligament. Revista do Hospital das Clínicas. 2000;55(3):83–86.

- Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia. 2009;13(4):343–403.

- Zhao LC, Lautz TB, Meeks JJ, Maizels M. Pediatric testicular torsion epidemiology using a national database: incidence, risk of orchiectomy and possible measures toward improving the quality of care. J Urol. 2011;186(5):2009–2013

- Testicular Torsion: Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2013 Dec 15;88(12):835-840. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2013/1215/p835.html

- Gatti JM, Patrick Murphy J. Current management of the acute scrotum. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16(1):58–63.

- Kapoor S. Testicular torsion: a race against time. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(5):821–827.

- Barteczko KJ, Jacob MI. The testicular descent in human. Origin, development and fate of the gubernaculum Hunteri, processus vaginalis peritonei, and gonadal ligaments. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2000;156:III–X, 1–98.

- Gordhan CG, Sadeghi-Nejad H. Scrotal pain: evaluation and management. Korean J Urol. 2015;56(1):3-11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4294852/

- Dogra V, Bhatt S. Acute painful scrotum. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:349–363.

- Callewaert PR, Van Kerrebroeck P. New insights into perinatal testicular torsion. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169(6):705–712.

- Nandi B, Murphy FL. Neonatal testicular torsion: a systematic literature review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27(10):1037–1040.

- Witherington R, Jarrell TS. Torsion of the spermatic cord in adults. J Urol. 1990;143(1):62–63.

- Favorito LA, Cavalcante AG, Costa WS. Anatomic aspects of epididymis and tunica vaginalis in patients with testicular torsion. Int Braz J Urol. 2004;30(5):420–424.

- Nguyen L, Lievano G, Ghosh L, Radhakrishnan J, Fornell L, John E. Effect of unilateral testicular torsion on blood flow and histology of contralateral testes. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34(5):680–683.

- Davis JE, Silverman M. Scrotal emergencies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011;29(3):469–484.

- Ciftci AO, Senocak ME, Tanyel FC, Büyükpamukçu N. Clinical predictors for differential diagnosis of acute scrotum. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004;14(5):333–338.

- Srinivasan A, Cinman N, Feber KM, Gitlin J, Palmer LS. History and physical examination findings predictive of testicular torsion: an attempt to promote clinical diagnosis by house staff. J Pediatr Urol. 2011;7(4):470–474.

- Canning DA, Lambert SM. Evaluation of the pediatric urology patient. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology, 10th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:3067–3084.

- Watkin NA, Reiger NA, Moisey CU. Is the conservative management of the acute scrotum justified on clinical grounds? Br J Urol. 1996;78(4):623–627.

- White WM, Brewer ME, Kim ED. Segmental ischemia of testis secondary to intermittent testicular torsion. Urology. 2006;68(3):670–671.

- Bomann JS, Moore C. Bedside ultrasound of a painful testicle: before and after manual detorsion by an emergency physician. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(4):366.

- Sessions AE, Rabinowitz R, Hulbert WC, Goldstein MM, Mevorach RA. Testicular torsion: direction, degree, duration and disinformation. J Urol. 2003;169(2):663–665.

- Corbett HJ, Simpson ET. Management of the acute scrotum in children. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72(3):226–228.

- Yang C Jr, Song B, Liu X, Wei GH, Lin T, He DW. Acute scrotum in children: an 18-year retrospective study. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(4):270–274.

- Bayne AP, Madden-Fuentes RJ, Jones EA, et al. Factors associated with delayed treatment of acute testicular torsion-do demographics or inter-hospital transfer matter? J Urol. 2010;184(4 suppl):1743–1747.

- Taskinen S, Taskinen M, Rintala R. Testicular torsion: orchiectomy or orchiopexy? J Pediatr Urol. 2008;4(3):210–213.

- Bolin C, Driver CP, Youngson GG. Operative management of testicular torsion: current practice within the UK and Ireland. J Pediatr Urol. 2006;2(3):190–193.

- Ringdahl E, Teague L. Testicular torsion. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(10):1739–1743.

- Informed Health Online [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Varicoceles: Overview. 2009 Aug 7 [Updated 2016 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279346

- Do I Have Testicular Cancer? https://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicular-cancer/do-i-have-testicular-cancer.html

- Key Statistics for Testicular Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicular-cancer/about/key-statistics.html