What is septicemia

Septicemia is also known as sepsis and often incorrectly called ‘blood poisoning’. “Sepsis is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body’s response to an infection injures its own tissues and organs” 1. Worldwide, one-third of people who develop sepsis die. Many who do survive are left with life-changing effects, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), chronic pain and fatigue organ dysfunction (organs don’t work properly) and/or amputations 2. Sepsis can be caused by any type of infection: bacterial, viral, fungal, or even parasitic. Many infections can be prevented simply by good and consistent hygiene. Others can be prevented through the use of vaccinations.

Conceptually, septicemia refers to sepsis with positive blood cultures, although it is an archaic term that is generally avoided today 3. Blood cultures are not commonly positive, in part because bacteria do not need to circulate in the bloodstream to induce sepsis, and in part because some patients are being treated empirically with antibiotics at the time of testing and before the diagnosis. Thus, the term septicemia has been abandoned 3. The term ‘septic shock’ remains current and is defined as a state in which sepsis is associated with cardiovascular dysfunction manifested by persistant hypotension despite an adequate fluid (volume) resuscitation to exclude the possibility of volume depletion as a cause of hypotension 3. Hypotension is operationally defined as the requirement for vasopressor therapy to maintain a mean arterial pressure of >65 mmHg and a plasma lactate level of >2 mmol per liter. An increased level of serum lactate is a hallmark of tissue hypo perfusion and septic shock, and is helpful in early diagnosis 3. The usual cut-off value for an abnormally high lactate level is ≥2 mmol per liter, but Casserly et al. 4 have recommended the use of a lactate level of ≥4 mmol per liter for inclusion in sepsis clinical trials.

Sepsis is a serious life-threatening medical emergency and can be fatal if not treated quickly. Sepsis happens when your body has an overwhelming immune response to a bacterial infection. The chemicals released into the blood to fight the infection trigger widespread inflammation. This leads to blood clots and leaky blood vessels. They cause poor blood flow, which deprives your body’s organs of nutrients and oxygen. In severe cases, one or more organs fail. In the worst cases, blood pressure drops and the heart weakens, leading to septic shock. If you suspect you or someone else has sepsis, call your local emergency services number for an ambulance.

Sepsis has been named as the most expensive in-patient cost in American hospitals in 2014 averaging more than $18,000 per hospital stay 5. With over 1.5 million sepsis hospital stays in 2014 per year, that works out to costs of $27 billion each year 5. Studies investigating survival have reported slightly different numbers, but it appears that on average, approximately 30% of patients diagnosed with severe sepsis do not survive. Up to 50% of survivors suffer from post-sepsis syndrome. Until a cure for sepsis is found, early detection is the surest hope for survival and limiting disability for survivors 5.

When bacteria get into a person’s body, they can cause an infection. If that infection isn’t stopped, it can cause sepsis. Sepsis happens when an infection you already have —in your skin, lungs, urinary tract, or somewhere else—triggers an overwhelming immune response throughout your body.

Usually, your immune system keeps an infection limited to one place. This is known as a localized infection. Your body produces white blood cells, which travel to the site of the infection to destroy the germs causing infection. A series of biological processes occur, such as tissue swelling, which helps fight the infection and prevents it spreading. This process is known as inflammation.

If your immune system is weak or an infection is particularly severe, it can quickly spread through the blood into other parts of the body. This causes the immune system to go into overdrive, and the inflammation affects the entire body. This can cause more problems than the initial infection, as widespread inflammation damages tissue and interferes with blood flow. The interruption in blood flow leads to a dangerous drop in blood pressure, which stops oxygen reaching your organs and tissues.

Without timely treatment, sepsis can rapidly lead to tissue damage, organ failure, and death.

In severe cases, one or more organs fail. In the worst cases, blood pressure drops, the heart weakens, and the patient spirals toward septic shock. Once this happens, multiple organs—lungs, kidneys, liver—may quickly fail, and the patient can die.

Sepsis is a major challenge in hospitals, where it’s one of the leading causes of death. It is also a main reason why people are readmitted to the hospital. Sepsis occurs unpredictably and can progress rapidly.

Anyone can get sepsis, but the risk is higher in:

- People with weakened immune systems

- Infants and children (under 1 years of age)

- The elderly (65 years or older)

- People with chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, AIDS, cancer, leukemia, lung disease and kidney or liver disease

- People suffering from a severe burn or physical trauma

- People receiving medical treatment that weakens their immune system – such as chemotherapy or long-term steroids

- Pregnant women

- People who have just had surgery, or have wounds or injuries as a result of an accident

- People who are on mechanical ventilation – where a machine is used to help you breathe

- People who have drips or catheters attached to their skin

- People who are genetically prone to infections

- Sepsis is a particular risk for people already in hospital because of another serious illness.

The risk of sepsis can be reduced by getting all recommended vaccines. In the hospital, careful hand washing can help prevent hospital-acquired infections that lead to sepsis. Prompt removal of urinary catheters and IV lines when they are no longer needed can also help prevent infections that lead to sepsis.

Common symptoms of sepsis are fever, chills, rapid breathing and heart rate, rash, confusion, and disorientation. Doctors diagnose sepsis using a blood test to see if the number of white blood cells is abnormal. They also do lab tests that check for signs of infection.

People with sepsis are usually treated in hospital intensive care units (ICUs). Doctors try to treat the infection, sustain the vital organs, and prevent a drop in blood pressure. Many patients receive oxygen and intravenous (IV) fluids. Other types of treatment, such as respirators or kidney dialysis, may be necessary.

Medical treatments include:

- Oxygen to help with breathing

- Fluids given through a vein

- Medicines that increase blood pressure

- Dialysis if there is kidney failure

- A breathing machine (mechanical ventilation) if there is lung failure

Sometimes, surgery is needed to clear up an infection.

Outlook (Prognosis)

- Sepsis is often life threatening, especially in people with a weak immune system or a long-term (chronic) illness.

- Damage caused by a drop in blood flow to vital organs such as the brain, heart, and kidneys may take time to improve. There may be long-term problems with these organs.

Sepsis symptoms in children under five

Go straight to emergency department or call your local emergency services number if your child has any of these symptoms:

- looks mottled, bluish or pale

- is very lethargic or difficult to wake

- feels abnormally cold to touch

- is breathing very fast

- has a rash that does not fade when you press it

- has a fit or convulsion

Get medical advice urgently

If your child has any of the symptoms listed below, is getting worse or is sicker than you’d expect (even if their temperature falls), trust your instincts and seek medical advice urgently.

Temperature

- temperature over 100.4 °F (38 °C) in babies under 3 months

- temperature over 102.2 °F (39 °C) in babies aged three to 6 months

- any high temperature in a child who cannot be encouraged to show interest in anything

- low temperature (below 96.8 °F (36 °C) – check 3 times in a 10-minute period)

Breathing

- finding it much harder to breathe than normal – looks like hard work

- making “grunting” noises with every breath

- can’t say more than a few words at once (for older children who normally talk)

- breathing that obviously “pauses”

Toilet/nappies

- not had a wee or wet nappy for 12 hours

Eating and drinking

- new baby under 1 month old with no interest in feeding

- not drinking for more than 8 hours (when awake)

- bile-stained (green), bloody or black vomit/sick

Activity and body

- soft spot on a baby’s head is bulging

- eyes look “sunken”

- child cannot be encouraged to show interest in anything

- baby is floppy

- weak, “whining” or continuous crying in a younger child

- older child who’s confused

- not responding or very irritable

- stiff neck, especially when trying to look up and down

If your child has any of these symptoms, is getting worse or is sicker than you’d expect (even if their temperature falls), trust your instincts and seek medical advice urgently.

How many people get sepsis?

Severe sepsis strikes more than a million Americans every year 6 and 15 to 30 percent of those people die. The number of sepsis cases per year has been on the rise in the United States 7. This is likely due to several factors:

- There is increased awareness and tracking of sepsis.

- People with chronic diseases are living longer, and the average age in the United States is increasing. Sepsis is more common and more dangerous in the elderly and in those with chronic diseases.

- Some infections can no longer be cured with antibiotic drugs. Such antibiotic-resistant infections can lead to sepsis.

- Medical advances have made organ transplant operations more common Link to external Web site. People are at higher risk for sepsis if they have had an organ transplant or have undergone any other procedure that requires the use of medications to suppress the immune system.

Are there any long-term effects of sepsis?

Many people who survive severe sepsis recover completely, and their lives return to normal. But some people, especially those with pre-existing chronic diseases, may have permanent organ damage. For example, in someone who already has impaired kidneys, sepsis can lead to kidney failure that requires lifelong dialysis.

There is also some evidence that severe sepsis disrupts a person’s immune system, making him or her more at risk for future infections. Studies have shown that people who have experienced sepsis have a higher risk of various medical conditions and death, even several years after the episode.

Chronic critical illness is occurring in a large proportion of patients who survive sepsis but remain hospitalized 8; >50% of patients in the ICU die within 3 months of sepsis and 60% have psychological disturbances 9. Only a minority of patients return to a functional lifestyle. Few patients who survive sepsis are discharged to home; the majority of patients are discharged to long-term nursing or rehabilitative facilities 3. Both age and length of time in the ICU have been shown to be independent variables for long-term survival and functional recovery 10. Patients >55 years of age and those who remained in the ICU for >14 days have the highest mortality rates post-discharge 3.

Even less is known about the long-term consequences on functional and cognitive recovery after sepsis. Intensive care specialists have recognized a syndrome in survivors of critical illness, including sepsis, termed post-ICU syndrome, which is characterized by insomnia, nightmares, fatigue, depression, loss of cognitive function and loss of self-esteem 11. Almost half of the individuals who survived sepsis report at least three of these symptoms 12. These individuals demonstrate cognitive deficits in verbal learning and memory up to 2 years after the hospital discharge 13. Interestingly, these cognitive deficits were associated with a significant reduction of left hippocampal volume compared with healthy controls. Patients with sepsis also had more low-frequency electroencephalogram activity indicating generalized brain dysfunction and not focal damage. Sepsis has also been known to induce post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in many patients 14. An increased incidence of PTSD in individuals who survived sepsis is also associated with pre-sepsis depression and delirium while in intensive care 14.

Several studies have used surveys to examine functionality after hospital discharge 15. The general consensus has been that patients who survive sepsis have a prevalence of moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment 10% higher than the general population. Equally important, patients who survived sepsis had a much higher frequency of new impairments than their age-matched counterparts.

The underlying causes of these functional and physical declines are unknown, but there are many possible reasons. Primary causes might include ICU-acquired weakness owing to both inactivity and immobilization, as well as from inflammation, corticosteroid and neuromuscular blockers commonly used in sepsis treatment. According to Poulson et al. 16, in 81% of the patients who survived sepsis, loss of muscle mass at 1 year was the main cause of decreased physical function. In addition, direct neuronal damage and delirium may also contribute to lower physical functioning.

Septicemia causes

Many types of microbes can cause sepsis, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses. However, bacteria are the most common cause. In many cases, doctors cannot identify the source of infection. The symptoms of sepsis are not caused by the germs themselves. Instead, chemicals the body releases cause the response.

Severe cases of sepsis often result from a body-wide infection that spreads through the bloodstream. Invasive medical procedures such as inserting a tube into a vein can introduce bacteria into the bloodstream and bring on the condition. But sepsis can also come from an infection confined to one part of the body, such as the lungs, urinary tract, skin, or abdomen (including the appendix).

A bacterial infection anywhere in the body may set off the response that leads to sepsis. Common places where an infection might start include the:

- Bloodstream

- Bones (common in children)

- Bowel (usually seen with peritonitis)

- Kidneys (upper urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis or urosepsis)

- Lining of the brain (meningitis)

- Liver or gallbladder

- Lungs (bacterial pneumonia)

- Skin (cellulitis)

For people in the hospital, common sites of infection include intravenous lines, surgical wounds, surgical drains, and sites of skin breakdown, known as bedsores or pressure ulcers.

Sepsis commonly affects infants or older adults.

Sepsis is related to a number of other diseases and conditions, many of which are risk factors for developing sepsis, including:

- Animal Bites

- Appendicitis

- ARDS (Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome)

- Autoimmune Diseases

- Bacterial Infections

- Blood Poisoning

- Burns

- Clostridium difficile

- Cancer

- Cellulitis

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

- Dental Health

- Diabetes

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC)

- Ebola

- Fungal Infections

- Gallstones

- Group A Streptococcus

- Group B Streptococcus

- Healthcare-acquired Infections

- HIV/AIDS

- Impaired Immune System

- Influenza

- Invasive Devices

- Intestinal E. Coli Infections

- IV Drug Use

- Joint Replacements

- Kidney Stones

- Kidney Transplants

- Liver Disease

- Malaria

- Meningitis

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

- Necrotizing Fasciitis

- Paralysis

- Parasitic Infections

- Parkinson’s Disease

- Perforated Bowel

- Pneumonia

- Pregnancy & Childbirth

- Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

- Strep Throat

- Surgery

- Tattoos & Body Piercings

- Toxic Shock Syndrome

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

- Viral Infections

Sepsis Prevention

Sepsis can be caused by any type of infection: bacterial, viral, fungal, or even parasitic. Many infections can be prevented simply by good and consistent hygiene. Others can be prevented through the use of vaccinations.

Vaccinations

Viral infections, such as influenza (the flu), chicken pox, and HIV, are caused by viruses. Viruses are microscopic organisms that must live inside a living host, such as humans. Although each virus is different, viruses generally don’t survive for long outside the host.

Usually when you have a viral illness, your body produces antibodies that keep you from getting the illness again – they make you immune. Vaccines have been developed for many viruses, such as chicken pox (varicella), tetanus, and polio. These vaccines, sometimes called immunizations, trick your body into thinking that it has been infected with the virus – which then makes you immune to actually getting the illness.

Caring for wounds

Every cut, scrape, or break in the skin can allow bacteria to enter your body that could cause an infection. For this reason, it’s essential that all wounds be cleaned as quickly as possible and be kept clean. They should also be monitored for signs of an infection.

Cleaning open wounds:

- Always wash your hands before touching an open wound. If possible, wear clean disposable gloves.

- If the wound is deep, gaping, or has jagged edges and can’t be closed easily, it may need stitches. See your healthcare provider as soon as possible.

- If the wound does not appear to need stitches, rinse it and the surrounding area with clean (not soapy) water. Gently running water over the wound can help remove any dirt or debris that may be inside. If you believe that there is still debris in the wound, this should be checked by a healthcare provider.

- If desired, apply an antibiotic cream or ointment.

- Cover the wound to protect it from dirt if necessary.

- Watch for signs of infection: redness around the wound, skin around the wound warm to touch, increased pain, and/or discharge from the wound. Consult your physician or nurse practitioner if you suspect you may have an infection.

Blisters: If you have a blister, do not pop it or break it. The blister is a protective barrier and breaking it introduces an opening in your skin. If the blister does break, keep the area clean and monitor for signs of infection.

Treating infections

Bacterial infections

Bacteria can cause infections in many parts of the body, such as a cut or bug bite on your arm, your kidneys or bladder, even your lungs (pneumonia). If you have been diagnosed with a bacterial infection, you will likely be prescribed antibiotics for treatment. Antibiotics are medications that kill bacteria or stop them from reproducing.

Some antibiotics work against several types of bacteria, while others are for specific bacteria only. Partly because of overuse and misuse of these medications, some bacteria are becoming resistant to certain antibiotics. This is making it harder to treat infections. For this reason, it is essential that people take antibiotics only when necessary and exactly as prescribed.

What to do when you are prescribed antibiotics:

- Follow the instructions regarding how the medication should be taken – with or without food, before or after meals.

- Take it on time (example: once a day, every six hours)

- Finish the full course (7 days, 10 days, etc.), even if you feel better sooner. The symptoms will disappear before the bacteria have been completely eliminated.

- Store the antibiotics as directed to preserve its strength.

What not to do with antibiotics:

- Do not ask your physician or nurse practitioner for a prescription for an infection not caused by bacteria. Antibiotics do not work on viruses, such as colds or the flu, or other illnesses not caused by bacteria.

- Do not take someone else’s antibiotics, even if you do have a bacterial infection. It may not be the correct type or dosage, or it may have expired. It can be dangerous to take expired antibiotics.

Viral infections

Most viral infections run their course without treatment, but some viral infections may be treated with anti-viral medications. If you are ill and don’t seem to be getting better, are getting worse or are developing new symptoms, are having difficulty breathing, or are concerned, please consult your healthcare professional. Sometimes, medications may be prescribed for the symptoms caused by the virus.

Fungal and parasitic infections

Infections caused by fungi or parasites must be treated with specific medications that will eliminate the cause.

Hand washing

Washing our hands is a simple task that we all do every day, several times a day. However for hand washing to be effective, it needs to be done properly and possibly more frequently than many people do already.

Generally, to wash your hands well, you simply need to use running water (to help wash the debris from your hands), lather your hands well (making sure to rub between each finger and under your nails), and dry your hands thoroughly with a clean towel.

If you are using a hand sanitizer (waterless cleanser), use the same motions of rubbing your hands together, in between your fingers and remembering the tops of your hands and your thumbs. Your hands should be dry before touching objects.

If you’re wondering whether to use a waterless cleanser or soap and water, the general belief is that soap and water are best for hands are visibly dirty or after activities, such as toileting. Hand sanitizers are good for when hands are not visibly dirty, but you know they need to be cleaned.

Teaching children to wash their hands

Children have many things they want to do and washing their hands may not be something they see as important. However, they do need to learn how to wash their hands properly and when they should be washed.

Obviously, children should wash their hands when they are dirty, but here is a list of other times when washing their hands is a must:

- Before eating or handling food

- After using the bathroom

- After blowing their nose or coughing

- After touching pets or other animals

- After being outside the home, such as playing outside, going to school, or shopping

For people caring for or living with someone who is immunocompromised

Someone who is immunocompromised has a low immune system, which makes it easier for them to develop infections and harder to fight them. When caring for or coming in contact with someone whose immune system is low, it’s important to reduce the infection risk as much as possible so the routine for washing your hands is stricter. While it may take a little longer to go through the steps, they are important in limiting the chances of transferring an infection to someone who may have a hard time fighting it.

- Remove rings and watches so you can clean the areas where they rest against your skin.

- Wet your hands with warm running water.

- Using soap, preferably liquid, rub your hands together to make a lather. Make sure that your fingertips rub into the areas between the fingers (webs) of the opposite hand.

- With each hand, wash the top of your other hand, not just the inside (palms). Don’t forget the thumbs, which are often neglected. Clean under your nails and let the water run under them as well.

- Go up to your wrists when washing.

- Hand washing should take at least 10 to 15 seconds. This is about how long it takes to sing “Happy Birthday,” twice quickly or once if slowly.

- Rinse your hands well and then dry with a clean towel. Pat them gently rather than rubbing vigorously, to protect your skin from becoming irritated.

- Use this towel to turn off the tap, to prevent recontaminating your hands.

Not all infections can be prevented and as a result, not all cases of sepsis can be prevented. However, by following these basic rules, you can decrease your risk becoming ill.

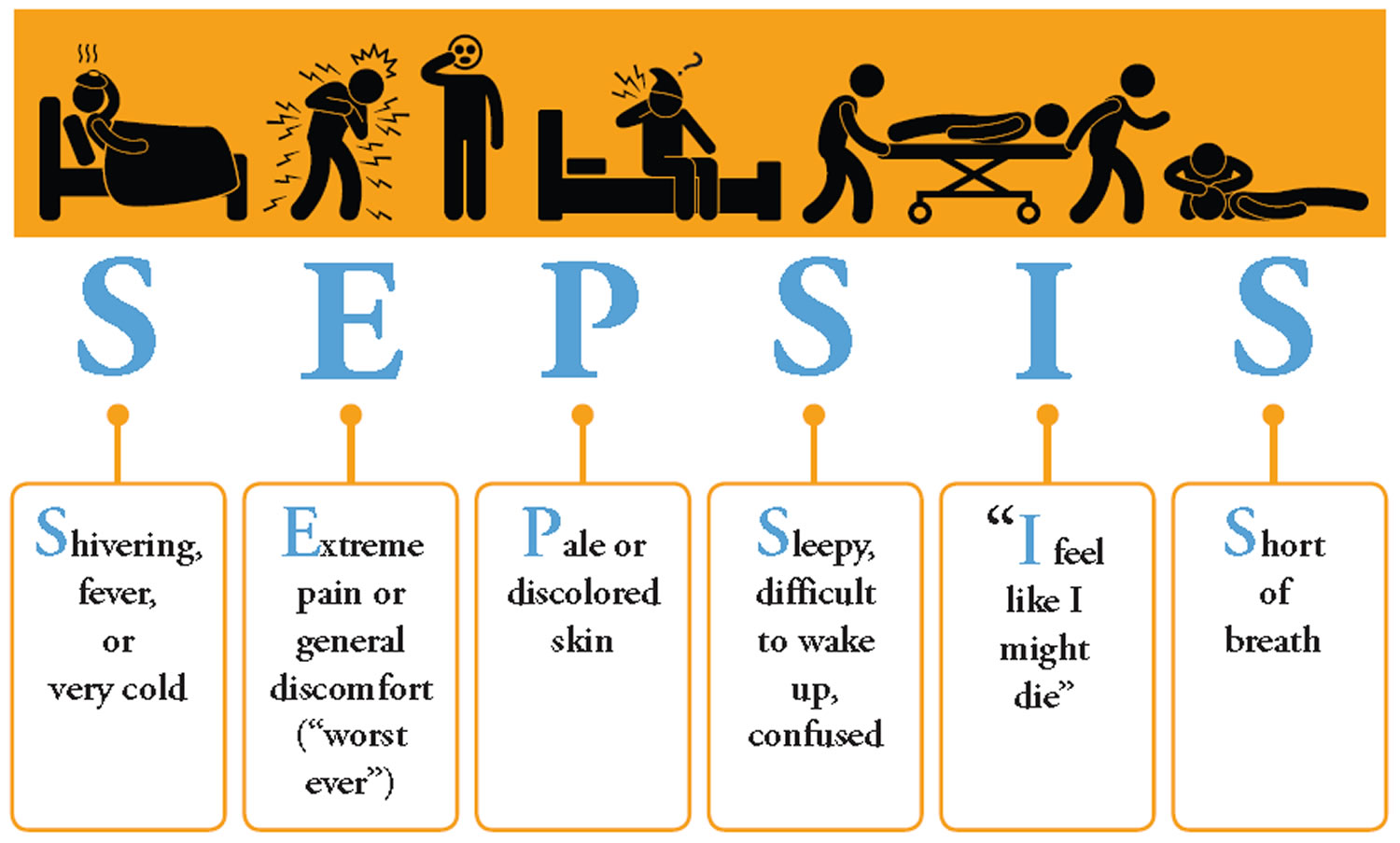

Septicemia signs and symptoms

Common symptoms of sepsis are fever, chills, rapid breathing and heart rate, rash, confusion, and disorientation. Many of these symptoms are also common in other conditions, making sepsis difficult to diagnose, especially in its early stages.

Symptoms of sepsis that you might experience can include a combination of any of the following:

- Confusion or disorientation

- Shortness of breath

- Extreme pain or discomfort

- Clammy or sweaty skin

- Fever

- Chills

- Rapid breathing and heart rate

- Tiredness

- Headaches

If sepsis gets worse, symptoms can include:

- Confusion

- Nausea and vomiting

- Difficulty breathing

- Mottled skin

- A sudden drop in blood pressure

Signs of sepsis that your doctor or nurse can measure include either of the following:

- High heart rate

- Fever, shivering, or feeling very cold

Get medical care IMMEDIATELY if you suspect sepsis or have an infection that’s not getting better or is getting worse.

Septicemia diagnosis

Doctors will start by checking for the symptoms mentioned above. Many of the signs and symptoms of sepsis, such as fever and difficulty breathing, are the same as in other conditions, making sepsis hard to diagnose in its early stages.

They may also test the person’s blood for an abnormal number of white blood cells or the presence of bacteria or other infectious agents. Doctors may also use a chest X-ray or a CT scan to locate an infection.

Doctors diagnose sepsis using a number of physical findings such as:

- Fever

- Low blood pressure

- Increased heart rate

- Difficulty breathing

Doctors also perform lab tests that check for signs of infection or organ damage.

Measure Lactate

- Patients with a suspected or diagnosed infection and a high lactate are at increased risk of adverse outcomes 17.

- Get a venous or arterial blood lactate level early in patients with suspected infection and sepsis but normal or mildly abnormal vital signs 18.

- Also, get a lactate level if uncertain about the presence of shock to detect occult cases.

- Elevated blood lactate is associated with higher risk for the development of overt septic shock and poor outcome.

- Lactate greater than 2 mmol/L is abnormal, and levels above 4 mmol/L often mean occult hypoperfusion and should trigger resuscitation.

- Patients with a history of cirrhosis or renal failure can have a slightly higher baseline blood lactate, but elevated lactate is still an important measurement in these populations.

Septicemia treatment

Doctors typically treat people with sepsis in hospital intensive care units (ICUs). Doctors try to stop the infection, protect the vital organs, and prevent a drop in blood pressure. This almost always includes the use of antibiotic medications and fluids. More seriously affected patients might need a breathing tube, kidney dialysis, or surgery to remove an infection. Despite years of research, scientists have not yet developed a medicine that specifically targets the aggressive immune response seen with sepsis.

Research shows that rapid, effective sepsis treatment includes:

- Giving antibiotics

- Maintaining blood flow to organs

- Treating the source of the infection

Doctors and nurses treat sepsis with antibiotics as soon as possible. Many patients receive oxygen and intravenous (IV) fluids to maintain blood flow and oxygen to organs. Other types of treatment, such as kidney dialysis or assisted breathing with a machine, might be necessary. Sometimes surgery is required to remove tissue damaged by the infection.

Give 1 liter crystalloid bolus to start and 30 mL/kg target in an hour 19

- Give more fluids in 500-mL to 1,000-mL increments based on the clinical response.

- The recommended target volume of initial fluid in the first hour is 30 mL/kg, followed by maintenance fluids if improved, otherwise continue bolus therapy 20

- A history of heart failure, liver failure, or renal failure is not a contraindication to fluid resuscitation. These patients might need less total fluid or smaller boluses with more frequent reassessment of intravascular volume status.

- Using adequate, large peripheral intravenous access for early resuscitation might prevent the need for central venous catheterization due to the ability to rapidly deliver fluids 20.

- A central venous catheter above the diaphragm is optimal, allowing venous pressure or oxygenation assessment if needed.

- 0.9% saline or balanced plasma solutions (Plasma-Lyte or Ringer’s) are equally effective, recognizing high volumes of saline might induce acidosis and renal dysfunction 21.

There is not a routine role for colloid solutions or blood products for shock therapy alone. Consider red cell transfusion for those with Hgb 7 g/dL or less 22.

DO NOT DELAY fluid and vasopressor therapy. Prompt resuscitation of septic shock patients is associated with more rapid resolution and improved survival rates 21.

- Vasopressors – Physicians prescribe vasopressors to patients are in shock and whose blood pressures have dropped dangerously low. The vasopressors act by constricting or tightening up the blood vessels, forcing the blood pressure to go up.

Get Infective Source Cultures Quickly 23

- Obtain appropriate cultures before antibiotics are initiated, but do not delay antibiotic administration solely to complete this task. Urine and blood cultures are commonly and easily obtained.

- Microbiologic samples allow for later tailoring of antibiotics.

- To optimize the identification of causative organisms, obtain at least two blood cultures before antibiotics, but do not delay antibiotic administration.

- Culture other sites, tissues, or fluids (cerebrospinal fluid, wounds, respiratory secretions) that might be the source of infection; these do not sterilize quickly and can be sampled as antibiotics are given.

- Adequate soft tissue and respiratory samples are often hard to obtain in the emergency department.

- Surrogate tests for bacterial infection and inflammation (C-reactive protein and procalcitonin) often show elevated levels but cannot currently effectively guide emergency department care in adult patients with sepsis or septic shock 24.

Give Antibiotics EARLY

- Give early appropriate antibiotics, ideally within the first hour of recognition.

- Delays in appropriate antibiotics can increase mortality rates 25.

- Choose based on suspected site and local patterns and evidence-based guidelines for specific types of infections 26.

- Broader antimicrobial therapy including antifungals might help in patients with immunosuppression or neutropenia.

Get source of infection control if possible 27

- Consider removing an intravascular device if suspected as the source of infection.

- Obtain appropriate consults (surgical or interventional radiology) when needed for source control.

Remeasure Lactate

- Remeasure lactate at least 1 to 2 hours (too soon does not help) after starting resuscitation in patients with initially abnormal lactate to help gauge progress.

- Persistence of elevated lactate, even in the absence of hypotension, is associated with poor outcomes; ongoing resuscitation is optimal 28.

- If lactate was elevated initially, a primary goal should be achievement of a relative lactate clearance of at least 10% 29.

- Epinephrine infusion or large-volume Lactated Ringer’s solution can impair clearance and hinder remeasurement assessments.

Reassess after boluses

- Look for signs of adequate fluid resuscitation or any complications from volume therapy 21.

- There is no singular ideal total fluid target, but commonly 4 to 6 L of total IV crystalloid solution is needed during the first 6 hours 30.

- Early titrated but aggressive fluid resuscitation is more important than any specific prescribed method of delivering or reassessing therapy.

It is best to use more than one method to assess resuscitation adequacy. Methods to measure intravascular volume or fluid responsiveness include the following 21:

- Bedside vital sign assessment (including shock index); and

- Clinical examination to assess perfusion and volume status; or ANY TWO of the following:

- Passive leg raises, pulse pressure variation >/= 13% (if arterial line placed) or heart rate variability to assess volume responsiveness 31; or

- Ultrasound assessment of vascular filling; or

- Stroke volume variation3; or

- Central venous pressure measurement (target 8-12 mm Hg while recognizing a trend is more important than one absolute value) or central venous oximetry (targeting 70%); or

- Repeat serum lactate level if elevated initially (should drop by 10% or more in 1 to 2 hours if resuscitation is adequate) 29

Again, DO NOT DELAY fluid and vasopressor therapy. Prompt resuscitation of septic shock patients is associated with more rapid resolution and improved survival rates 21.

Repeat vital signs. Check blood pressure, heart rate, shock index – look for changes.

Monitor Patient Response

- Titrate further fluids/pressors to patient response.

- Vasopressors are often needed.

Address ongoing hypotension

- In PATIENTS WITH PROFOUND OR ONGOING HYPOTENSION after fluid resuscitation or those who have signs of volume overload and signs of shock, USE CONTINUOUS IV NOREPINEPHRINE, targeting a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg 32.

- A well-secured large-bore peripheral catheter may be used to initiate therapy for the short term until central venous access is secured.

- Epinephrine is an option but can have more complications and less effect than norepinephrine.

- Higher blood pressure targets (mean arterial pressure >65 mm Hg) do not confer a better outcome.

Additional Possible Treatments

Since all patients are different and the causes of sepsis are many, not every available treatment is right for each patient. To find out what treatment is being given to you or your loved one and why, speak with your health care provider.

Here are treatments and medications that may be given to a patient with sepsis or who is in septic shock:

- Arterial lines – An arterial line may be inserted to help monitor and provide care. Aterial lines are usually only seen in intensive care units. These are not used to give fluids or medications but to obtain bloods samples from the artery, rather than the vein. Intensive care staff can also monitor blood pressure through the arterial line.

- Central venous catheter – Often, it is easier to insert a central venous catheter (central line) into a patient in an intensive care unit because it simplifies giving fluids and antibiotics by IV.

- Corticosteroids – Although doctors don’t know why corticosteroids work for some patients who have sepsis and not others, they can be helpful. Corticosteroids can help reduce inflammation in the body and depress the immune system, making it less active.

- Kidney dialysis – also called renal replacement therapy, dialysis may be necessary if the kidneys cannot filter the blood as they should. One of the kidneys’ main role is to filter toxins out of the blood.

- Mechanical ventilation – Patients who have developed severe sepsis or have gone into septic shock may need help to breathe as they are no longer able to do so on their own. They would be intubated and the tube attached to a ventilator.

- Oxygen – Patients are generally given oxygen, by mechanical ventilator, mask or nasal cannula, to ensure the body has enough oxygen in its system.

- PreSep(tm) catheter – this type of catheter was developed to help intensive care unit staff by monitoring the oxygen levels in blood that is returning to the heart.

- Pulmonary artery catheter – this type of catheter is inserted into the pulmonary artery – the blood vessel that carries blood from the heart to the lungs where the blood can be supplied with oxygen. “Pulmonary” means something is related to the lungs.

- Merinoff symposium 2010: sepsis”-speaking with one voice. Czura CJ. Mol Med. 2011 Jan-Feb; 17(1-2):2-3.

- Sepsis and Prevention. https://www.sepsis.org/sepsis-and/prevention/

- Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL, Opal SM, Reinhart K, Turnbull IR, Vincent J-L. Sepsis and septic shock. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2016;2:16045. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5538252/

- Casserly B, et al. Lactate measurements in sepsis-induced tissue hypoperfusion: results from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign database. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:567–573.

- Definition of Sepsis. https://www.sepsis.org/sepsis/definition/

- Hershey TB, Kahn JM. State sepsis mandates—a new era for regulation of hospital quality. N Engl J Med 2017 May 21; 376:2311-2313. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1611928

- Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med 2013 May; 41(5):1167-74. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23442987

- Vanzant EL, et al. Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome after severe blunt trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:21–29. discussion 29–30.

- Nelson JE, et al. The symptom burden of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1527–1534.

- Baldwin MR. Measuring and predicting long-term outcomes in older survivors of critical illness. Minerva Anestesiol. 2015;81:650–661

- Mehlhorn J, et al. Rehabilitation interventions for postintensive care syndrome: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:1263–1271.

- Battle CE, Davies G, Evans PA. Long term health-related quality of life in survivors of sepsis in South West Wales: an epidemiological study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e116304

- Semmler A, et al. Persistent cognitive impairment, hippocampal atrophy and EEG changes in sepsis survivors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:62–69

- Parker AM, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1121–1129

- Dowdy DW, et al. Quality of life in adult survivors of critical illness: a systematic review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:611–620.

- Poulsen JB, Moller K, Kehlet H, Perner A. Long-term physical outcome in patients with septic shock. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:724–730.

- Levy MM, Fink M, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1250-1256.

- Gallagher EJ, Rodriguez K, Touger M. Agreement between peripheral venous and arterial lactate levels. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:479-483.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. https://www.acep.org/DART/

- Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Powers GS, et al. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1301-1311.

- Seymour CW, Rosengart MR. Septic shock. Advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2015;314:708-717.

- Holst L, Haase N, Wetterslev J, et. al. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1381-1391.

- Blot F, Schmidt E, Nitenberg G, et al. Earlier positivity of central venous- versus peripheral-blood cultures is highly predictive of catheter-related sepsis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:105-109.

- Simon L, Gauvin F, Amre DK, et al. Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels as markers of bacterial infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:206-217.

- Sterling SA, Miller WR, Pryor J, et al. The impact of timing of antibiotics on outcomes in severe sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(9):1907-1915.

- Kumar A, Ellis P, Arabi Y, et al. Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest. 2009;136:1237-1248.

- Jimenez MF, Marshall JC; International Sepsis Forum. Source control in the management of sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27 Suppl 1:S49-S62.

- Nguyen HB, Rivers EP, Knoblich BP, et al. Early lactate clearance is associated with improved outcome in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1637-1642.

- Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, et al. Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2010;303:739-746.

- Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Powers GS, et al. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med.. 2015;372:1301-1311

- Mackenzie DC, Noble VE. Assessing volume status and fluid responsiveness in the emergency department. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2014;1:67-77.

- Asfar P, Mezaiani F, Hamel JF, et al. High versus low blood pressure target in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1583-1593