Snapping scapula syndrome

Snapping scapula syndrome also called washboard syndrome, scapulothoracic syndrome or scapulocostal syndrome, is defined as an audible or palpable clicking of the scapula during movements of the scapulothoracic joint 1. Snapping scapula syndrome manifests as an audible or palpable clicking during the sliding movements of the scapula over the rib cage, often perceived during physical or professional activities 2. Snapping scapula syndrome can be caused by morphological alteration of the scapula and rib cage, by an imbalance in periscapular musculature forces (dyskinesia), or by neoplasia (bone tumors or soft tissue tumors). Snapping scapula syndrome typically affects young, active patients, who often report a history of pain, resulting from overuse, during rapid shoulder movements or during sports activities 3. These symptoms can have insidious onset, can occur after a change in the pattern of physical activity, or can be associated with trauma 4.

Scapular anatomy

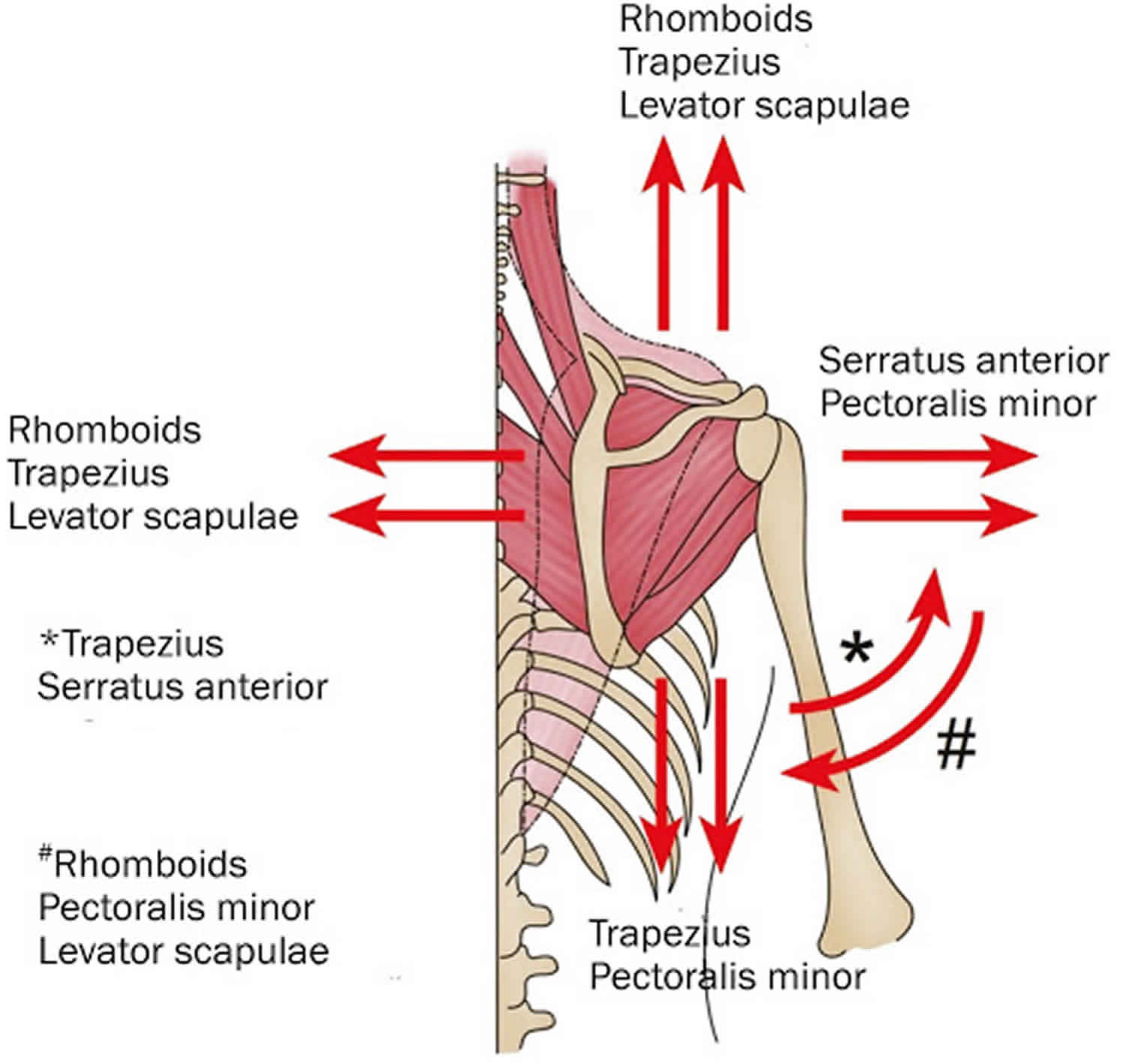

The scapula is a triangular-shaped bone, which articulates with the posterior chest wall. It is in conjunction with the upper limb by only the acromioclavicular joint, and therefore its stability is dependent on surrounding musculature 5. The elevator scapulae and rhomboids attach to the medial border of the scapula, whereas the subscapularis originates form its anterior surface 6. The serratus anterior originates from the ribs and inserts on the medial aspect of the scapular anterior surface. Thus subscapularis and serratus anterior create a sort of cushion between posterior chest wall and anterior scapular surface 7.

Two anatomic spaces are then identified: the subscapularis space and the serratus anterior space. The former is located between the chest wall, serratus anterior, and rhomboids; the latter is bounded by the serratus anterior, subscapularis, and axilla 8. Finally three out of the four muscles of the rotator cuff originate at the scapula: the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus from the posterior surface of the scapula and the subscapularis on the anterior surface.

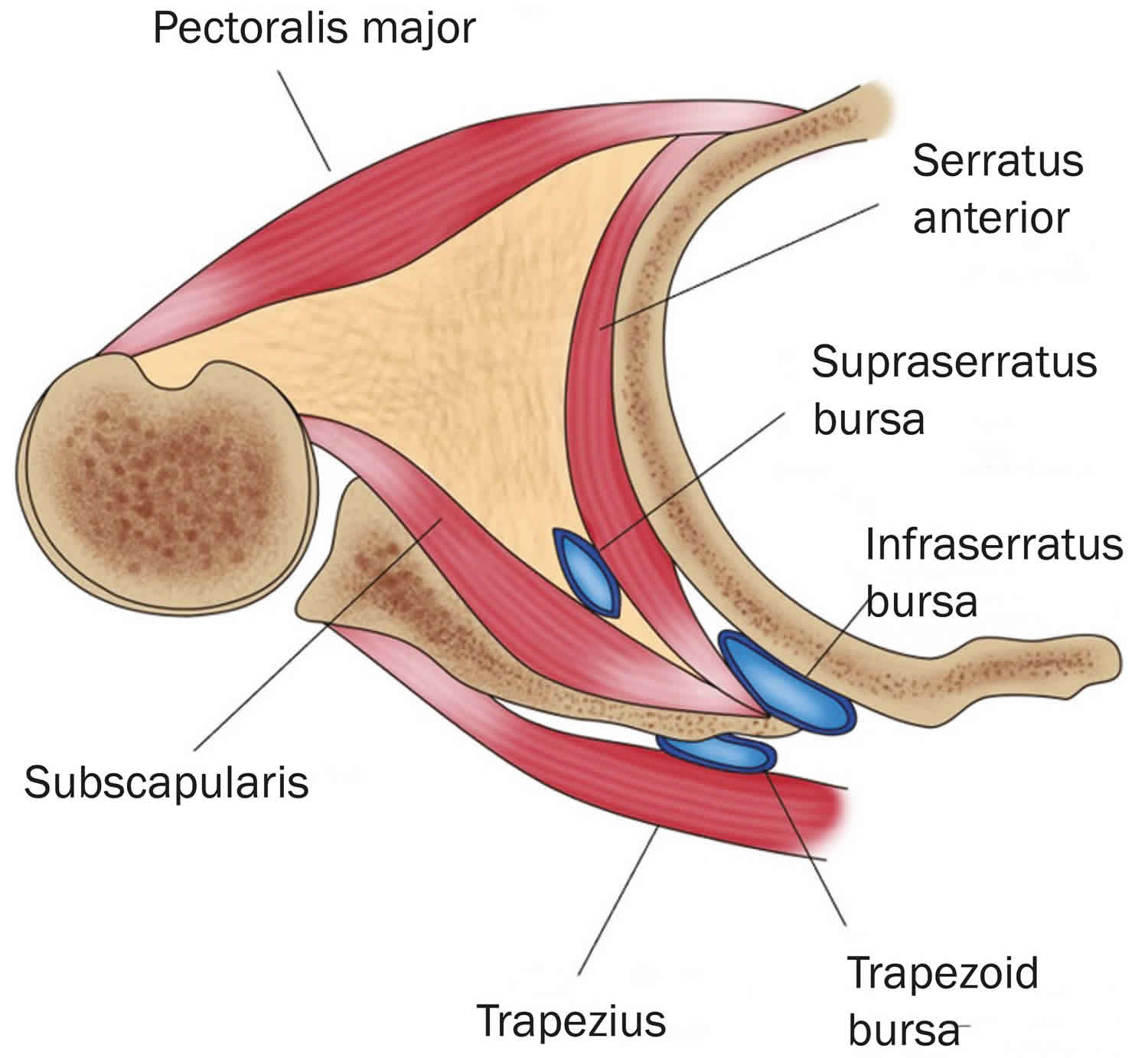

Several bursae have been described which are situated in areas where increased friction may occur and are virtual spaces filled by a synovial membrane 9. Kuhn et al. 6 described two major and four minor bursae in this joint. The first major bursa is located between the serratus anterior muscle and the chest wall (scapulothoracic or infraserratus bursa), while the second is situated between the subscapularis and the serratus anterior muscles (subscapularis or supraserratus bursa) (Figure 1). Anatomical research findings showed the two major bursae were also found in cases whereas each of the four minor bursae were absent 6. Biomechanics abnormalities of the scapulathoracic joint may lead to symptomatic inflammation of these bursae. Finally, there are several neurovascular structures surrounding the scapula. The accessory nerve goes through the elevator scapulae muscle close to the superomedial angle of the scapula and runs along the medial scapular border deep to the trapezius muscle 10.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the musculature and bursae involved in snapping scapula syndrome

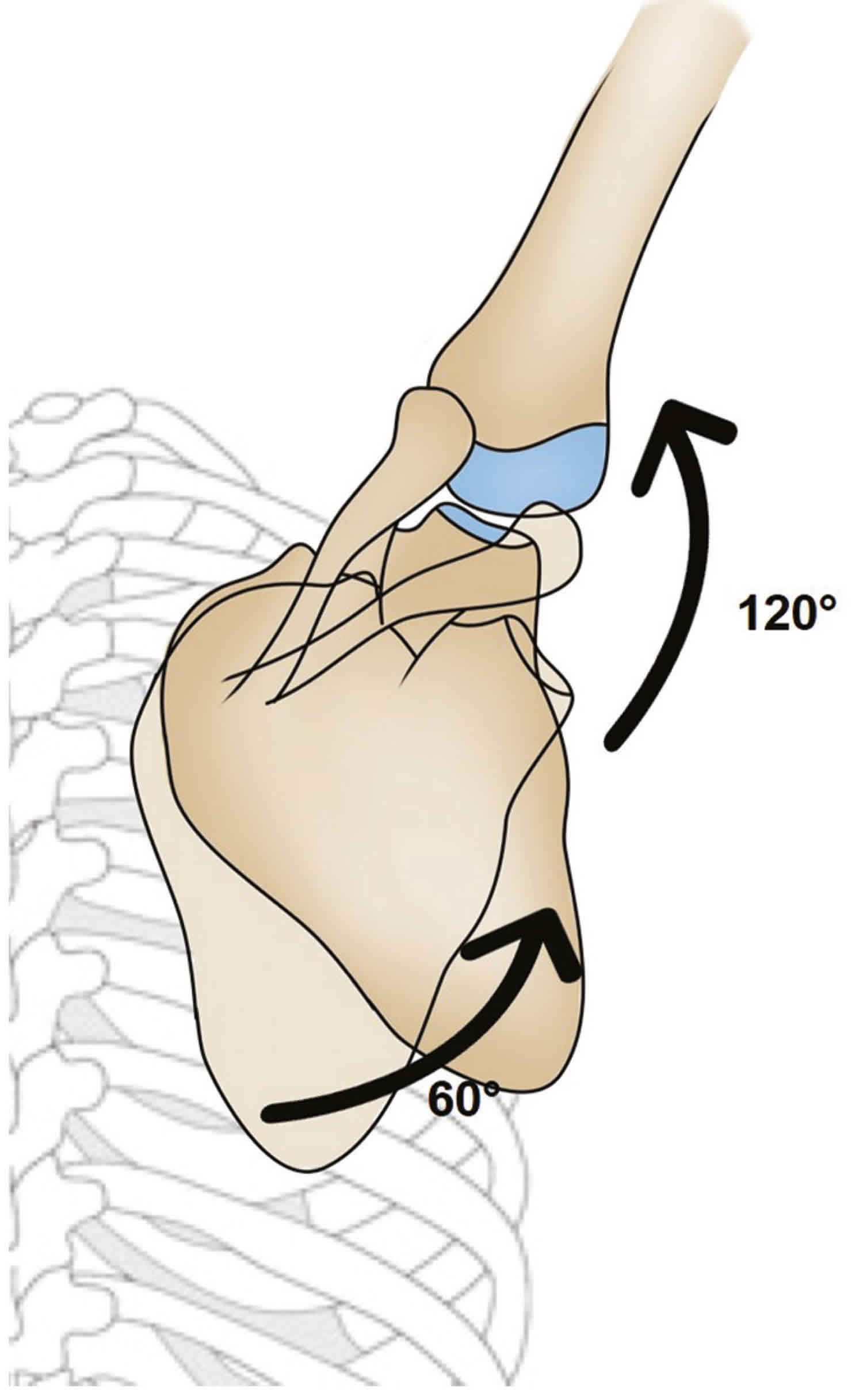

Figure 2. Scapulohumeral rhythm

Footnote: Schematic representation of the 2:1 scapulohumeral rhythm. For example, during a 180° abduction of the arm, 60° are achieved by rotation of the scapula and 120° are achieved by rotation of the humerus.

Snapping scapula syndrome causes

Superomedial angle of the scapula and anatomical variations

The scapulothoracic joint is cushioned by the serratus anterior and subscapularis muscles, as well as by the bursae 11. The superomedial angle, inferomedial angle, and medial border of the scapula are relatively less protected by underlying muscles and bursae, and the upper medial border and lower pole exhibit wide anatomical variability 11. When no obvious deformity is found, one should look for anatomical variations, such as an anomalous anterior curvature of the superomedial angle of the scapula, which is considered one of the main causes of the syndrome. The superomedial angle of the scapula has been measured in anatomical specimens and found to range from 124° to 162° (mean, 144.34 ± 9.09°) 11; when the angle is lower than 142°, the chances of scapular snapping increase 12. The superomedial angle is measured on the anterior surface of the scapula, with three anatomical reference points: the superior angle, the spine, and the inferior angle. A bone projection at the lower pole is the second most common site for symptoms 13.

The Luschka tubercle

The Luschka tubercle is a hook-shaped bony protuberance, located at the upper medial border of the scapula, which can reduce the space between the scapula and the rib cage and be a predisposing factor for scapular snapping 11.

Scapular dyskinesia, insufficiency of the serratus anterior muscle, and injury of the long thoracic nerve

Scapular dyskinesia, a common clinical finding, is defined as abnormal movement, positioning, or function of the scapula during shoulder movement. It can be the cause or consequence of many forms of shoulder pain and dysfunction. There are multiple causes of dyskinesia. Articulatory causes include acromioclavicular joint arthrosis, glenohumeral joint instability, and glenohumeral joint disorder. Musculoskeletal causes include thoracic kyphosis and nonunion of a clavicular fracture, as well as shortening, rotation, or angulation of the clavicle. Neurological causes include paralysis of the long thoracic nerve, paralysis of the eleventh cranial nerve, and cervical radiculopathy 14. The most common mechanisms involve imbalances of the intrinsic musculature, with inflexibility or inhibition of normal muscle activation 14. Scapular snapping can be present in dyskinesias, because the abnormal movements bring the extremities of the scapula into closer proximity to the rib cage. Regardless of the cause of dyskinesia, the final result in most cases is a scapula in pronation, which is not conducive to optimal shoulder function and results in subacromial space reduction with symptoms of impingement 14.

Sequelae of fractures of the scapula and rib cage

The sequelae of fractures of the scapula and rib cage can cause bone deformities. Such deformities can increase the friction among the structures of the scapulothoracic joint 15.

Bursitis

Scapulothoracic bursitis can occur after a single traumatic insult, as a result of repetitive movements of the scapulothoracic joint, or as a result of scapular dyskinesia. Abnormal scapular movement can be caused by overuse of the muscles, muscle imbalance, or pathological conditions of the glenohumeral joint 4. When the muscles of the costal surface of the scapula decrease in size, the scapula rotates forward, coming into closer proximity to the rib cage, generating friction with the chest wall during movement, causing inflammation in the scapulothoracic space 4.

Bone tumors

Osteochondroma, also known as exostosis, is the most common benign primary bone tumor of the scapula, being solitary in approximately 90% of cases and multiple, in the form of hereditary multiple exostoses, in approximately 10%. Such tumors are considered alterations of the growth plate, specifically its failure to increase in size during skeletal maturation 16. They usually involve the metaphysis of long bones and, more rarely, the scapula (in 4-6% of cases). An osteochondroma can be symptomatic, mainly due to its mass effect, creating the appearance of scapular winging, together with crackles, and altering the scapulothoracic movement. It can also cause neurovascular compression, fractures, inflammation of the bursa, or malignant transformation 16.. Although scapular chondrosarcoma is rare, the scapula is the second most common site of involvement of this disease, especially among men between 40 and 70 years of age 4.

Elastofibromas

An elastofibroma is a benign soft tissue tumor with slow growth and a prevalence rate of up to 24% in the elderly, being most common among women between 55 and 70 years of age. Elastofibromas are believed to occur in response to repetitive microtrauma caused by friction between the scapula and the chest wall. An elastofibroma is typically located at the lower pole of the scapula, deep within the serratus anterior and latissimus dorsi muscles. It can manifest as an increase in subscapular or infrascapular volume, moderate discomfort or pain, crackles, clicking (snapping), or a blocked scapula 17.

Snapping scapula syndrome symptoms

Patients often refer history of pain during overhead activities or repetitive overuse of the shoulder, or even a single traumatic injury 18; typically they describe an audible and palpable crepitus with active shoulder movements, including shrugging of shoulders 19. These symptoms may result from participation in sports activities, including swimming and throwing, or from other rapid overhead arm movements 20. Although the audible symptoms can be painless, it is common that pain is present and may be severe enough to limit most of daily activities. The location of the pain is mostly at the supero-medial angle or inferior pole of the scapula and sometimes an additional cervical irradiation can be referred 21. Under clinical evaluation, the physician can feel crepitus and hear the snapping in most patients. The crepitus is easily reproduced during arm movement because pain occurs generally with shoulder abduction. The crepitus may be accentuated with the compression of the superior angle of the scapula against the chest wall during arm abduction 22. Most of patients commonly have tenderness to palpation at the supero-medial border or inferior pole of the scapula 23. Due to muscle contracture and malfunction, patients can also claim pain at the palpation over the levator scapulae, trapezius, and/or rhomboid muscles. Pain is normally not reproducible with isometric movements 19. Pain and snapping generally decrease crossing the arm, thus lifting the scapula from the ribcage 7. The evaluation of scapular motion is crucial. When scapular asymmetry is detected, it can be the result of a scapular dyskinesis or underlying mass or space-occupying lesion. However pseudo-winging may be present as the patient compensates for pain 23. Scapulo-thoracic bursitis generally cause deep pain at the level of levator scapulae and the supero-medial angle of the scapula. Trapezoid bursitis is a rare cause of more superficial pain, referred over the junction of the spine and the medial border 21.

Snapping scapula syndrome diagnosis

Snapping scapula syndrome treatment

Snapping scapula syndrome treatment involves treating the underlying cause. Conservative treatment aims to correct muscles dysfunction, postural factors and scapular dyskinesis 24. However, since the major causes leading to the onset of snapping scapula are overuse and improper joint mechanics, initially the patient have to change his activities and rest the joint to calm the cycle of bursitis and scarring. Thus a course of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications is indicated to decrease inflammation 23 that can associated with additional conventional treatments including ice, heat, and ultra-sound treatments. Other researchers suggested the use of diathermy, ultrasound, and iontophoresis to the undersurface at the medial border of the scapula 25. After that pain is alleviated with the aforementioned physical treatments, patients can be directed to a standard program of physiotherapy.

Muscle imbalance should be corrected, strengthening weak muscles and stretching antagonist retracted ones. Abnormal posture or winging scapula must be addressed in order to restore proper joint mechanics. It is supposed that when scapulothoracic crepitus is related to soft tissue abnormalities, altered posture, scapular winging, or scapulothoracic dyskinesia, surgical intervention will not be required 26. Muscular stretching and strengthening and postural training are the most beneficial treatments. Postural training aims to minimize kyphosis, promote upright posture, and strengthen upper thoracic muscles. Thoracic kyphosis is associated with forward head, rounded shoulders, abducted and forward-tipped scapulae 27 and sub-occipital extension 28. The tightened muscles include pectoralis major and minor, levator scapulae, upper trapezius, latissimus dorsi, subscapularis, sternocleidomastoid, rectus capitis, and scalene muscles. Weakened muscles include the rhomboids, mid and lower trapezius, serratus anterior, teres minor, infra-spinatus, posterior deltoid, and longus colli or longus capitis. Restoring scapular strength establishes static proximal stability to provide a stable base of support 29. Because the scapula is responsible for static stability of the shoulder girdle, endurance training of these muscles is the key for scapular stability. This type of training necessitates low-intensity, high-repetition exercises. Strengthening of the subscapularis and serratus anterior are crucial since a weak serratus anterior muscle causes forward tilting of the scapula inducing crepitus 30. Scapular adduction and shoulder shrug exercises strengthen scapular stabilizers (serratus anterior, rhomboids, levator scapulae) that provide the correct scapula position (Figure 3A–C) 31. On the contrary, abduction and elevation of the scapula should be avoided because cause increased pressure and strain on the underlying musculature 5. All these exercises aim to resolve muscle imbalance and correct scapular motion thus reducing pain and functional impairment. Implementation of the rehabilitation program should be comprehensive. It is important the strengthening of the core or trunk of the body (the core is defined as the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex) 32, because it serves as the crossroads for energy transfer in all human movement, where the forces can move from the lower to the upper extremities or vice versa 33. However if pain persists, physical therapy must be avoided and local injection of anesthetics and steroids have to be considered 34. The technique for scapulothoracic injection is performed on the patient prone, with the shoulder in extension, internal rotation, and adduction and the hand that lies behind the back (“chicken-wing position”) 21. The needle (1.5-inch 22-to 25-gauge) is inserted parallel to the anterior border of the scapula, taking care not to penetrate so deep as to cause a pneumothorax. When the pain is referred at the inferior angle of the scapula, the needle is entered and directed laterally on the infero-medial border of the scapula. For the supero-medial bursa, the needle should be angled 45° laterally going from proximal to distal and entering just off the superior-medial tip of the scapula 5. Corticosteroid injections are usually repetead from 3 to 4 times per year 6; furthermore, the combination of local anesthetic with steroids injection can be considered as a dignostic test that give a high likelihood that scapular bursitis or crepitus is related to the patient’s pain when is followed by partial or complete pain relief 9. If all non-surgical measures fail to relieve the symptoms after 3 to 6 months, surgical options should be considered.

Figure 3. Snapping scapula exercises

Footnote: Exercises for scapular muscles rehabilitation (A), lower trapezius (B), anterior dentatus, (C), rhomboids.

[Source 3 ]Snapping scapula syndrome surgery

Surgical procedure should be undertaken when conservative treatment has not been effective in resolving pain and improve shoulder function. Indications for surgery must be carefully evaluated using the aforementioned clinical and radiographic criteria, excluding patients with cervical spine disorders and neurological impairment 35. Failure to have pain relief after a preoperative injection of anesthetic in the superomedial or inferomedial scapular angle, exactly in the site where the patient localize the pain, may be a contraindication to operative management 35. Operative treatment for snapping scapula was first described by Milch in 1950 36, who performed the procedure in local anesthesia asking the patient to identify the site of the scapula to be resected. Additional research findings showed good clinical results after open approach for bursectomy and partial resection of the superior or inferior scapular angle 37. Surgery is commonly performed with the patient in lateral decubitus or preferably in prone position, with the arm internally rotated to lift away the medial border of the scapula from the thoracic cage 38.

Recently, Ross et al. 39 have described a surgical approach on the patient in beach chair position with a spider device used to assist with protraction of the scapula. Anatomical landmark are drawn and the incision is located along the medial border of the scapula, subsequently we split the upper trapezius from the scapular spine to expose the superior angle of the scapula, taking care to identify and protect the spinal accessory nerve along the superior scapular edge laterally to the superomedial angle and levator scapulae 4. At this stage of the procedure, levator scapulae and rhomboids muscles must be detached or preferentially released subperiosteally to completely expose the anteromedial border of the scapula and having the tendinous insertions preserved and free to be reattached to their anatomical origin 40. The structure at risk during rhomboids detachment is the dorsal scapular nerve which is medially located, at an average distance of 2 cm from the medial scapular border 35. The bone surface of the scapula is now adequately exposed to isolate and resect the pathological bursa, spurs or other osseous abnormalities. At the end of the procedure rhomboids muscles are reattached with bone drill holes and the wound is closed in layers using absorbable sutures 40. The arm is protected in a sling for 4 weeks followed by a standard program of physiotherapy including exercises for the restoration of the range of motion and muscle strengthening. Several studies reported good to satisfactory results after open treatment of snapping scapula 41. Specifically, McCluskey and Bigliani 42 described the results of isolated bursectomy at the superior scapular angle (supraserratus bursa) as satisfactory in six cases and good in two cases, while the last case was complicated by spinal nerve accessory palsy who underwent to additional intervention for tendon transfer with poor long-term benefit. Sisto DJ et al. 43 reported that all 4 pitchers treated with open bursectomy of the inferior angle of the scapula (infraserratus bursa) had relief from pain and associated symptoms and returned to the same preoperative level in their sport activity. In a large case series of 17 patients treated with open procedure for scapulothoracic pain, Nicholson and Duckworth 40 reported satisfactory outcomes in all cases and in addition to the bursectomy they performed the resection of the supero-medial scapular angle in 5 out 17 cases and explored the scapulotrapezial bursa. Histological examination of the resected soft and bone tissues showed chronic inflammation and physiological bone architecture 40. Arthroscopy is a valid technically demanding alternative to conventional open approach in the treatment of symptomatic snapping scapula. Due to its low invasiveness, arthroscopic surgery guarantee several advantages compared with open procedure, such as decrease morbidity for preservation of muscles attachment, early postoperative rehabilitation and return to full function, good cosmesis, short hospital stays and higher patient’s compliance 44. Scapulothoracic arthroscopy was initially described with 2 medial scapular portals14, subsequently was added a third superior portal (“Bell’s portal”) 45. The procedure is performed on the patient in prone or lateral position with skin landmark drawn and the arm internally rotated, as described for the open surgical procedure (“chicken-wing position”) 46.

Following surgery the arm is protect in a sling. Passive mobilization begin the first postoperative day, the full active range of motion is achieved within 1–2 weeks, cautious strenghtening exercises are allowed after 30 days; the patients can return to their sports activity the third postoperative month.

Most case series studies on arthroscopic approach for snapping scapula reported good to excellent results 33. Blønd and Rechter 47 in a prospective follow-up study on twenty patients at 2.9 years after arthroscopic scapular bony resection, reported an increase of the median Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index score from 35 to 86; furthermore, 19 out of 20 patients indicated that they would undergo the surgery again. Millett et al. 21 in a retrospective study on 22 patients at a minimum of 2 years follow-up, treated with arthroscopic bursectomy and partial scapulectomy, reported a postoperative improvement of 20 points in ASES score, a Quick DASH score of 35 pints and a single assessment numeric evaluation (SANE) shoulder score of 73 points; the authors concluded that although significant pain and functional improvement can be expected after arthroscopic bursectomy and scapuloplasty, the average postoperative ASES and SANE scores remained lower than expected. Pavlik et al. 31 describing the results of a prospective study on ten patients underwent to scapulothoracic arthroscopy, reported that UCLA score at an average follow-up of 11.5 months, was excellent in 4, good in 5 and fair in 1; the authors concluded that the procedure was beneficial in the majority of the patients and highlighted the role of the superior portal to make the procedure easier to perform. Pearse et al. 34 in a retrospective case series study on thirteen patients, reported that 9 patients had an improvement in their symptoms with median Constant score of 87 points, while 4 felt that their symptoms were unchanged or worse with a median Constant score of 55 points; 8 out of 9 employed patients returned to their previous careers and 6 out of 9 patients who played sports returned to their preoperative level of sporting activity. It was interesting to note that bone was resected from the superomedial angle only if it appeared to be prominent during arthroscopy and this occurred only in 3 cases. Lien SB et al. 48 described a combined method using endoscopic bursectomy with mini-open partial scapulectomy for treating 12 cases of snapping scapula and reported a significant postoperative improvement in ASES score and Simple Shoulder Test, the snapping sound and pain improved in 10 out of 12 cases and all subjects returned to work.

References- Carvalho, Stefane Cajango de, Castro, Adham do Amaral e, Rodrigues, João Carlos, Cerqueira, Wagner Santana, Santos, Durval do Carmo Barros, & Rosemberg, Laercio Alberto. (2019). Snapping scapula syndrome: pictorial essay. Radiologia Brasileira, 52(4), 262-267. Epub August 19, 2019.https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-3984.2017.0226

- de Carvalho SC, Castro ADAE, Rodrigues JC, Cerqueira WS, Santos DDCB, Rosemberg LA. Snapping scapula syndrome: pictorial essay. Radiol Bras. 2019;52(4):262–267. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2017.0226 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6696755

- Merolla G, Cerciello S, Paladini P, Porcellini G. Snapping scapula syndrome: current concepts review in conservative and surgical treatment. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013;3(2):80–90. Published 2013 Jul 9. doi:10.11138/mltj/2013.3.2.080 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3711706

- Lazar MA, Kwon YW, Rokito AS. Snapping scapula syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2251–2262.

- Manske RC, Reiman MP. Nonoperative and operative management of snapping scapula. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1554–1565.

- Kuhn JE, Plancher KD, Hawkins RJ. Symptomatic scapulothoracic crepitus and bursitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:267–273.

- Carlson HL, Haig AJ, Stewart DC. Snapping scapula syndrome: Three case reports and an analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:506–511.

- Lesprit E, Le Huec JC, Moinard M, Schaeverbeke T, Chauveaux D. Snapping scapula syndrome: Conservative and surgical treatment. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2001;11:51–54.

- Percy EC, Birbrager D, Pitt MJ. Snapping scapula: A review of the literature and presentation of 14 patients. Can J Surg. 1988;31:248–250.

- Ruland LJ, III, Ruland CM, Matthews LS. Scapulothoracic anatomy for the arthroscopist. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:52–56.

- Aggarwal A, Wahee P, Harjeet, et al. Variable osseous anatomy of costal surface of scapula and its implications in relation to snapping scapula syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2011;33:135–140.

- Mozes G, Bickels J, Ovadia D. The use of three-dimensional computed tomography in evaluating snapping scapula syndrome. Orthopedics. 1999;22:1029–1033.

- Kuhne M, Boniquit N, Ghodadra N. The snapping scapula: diagnosis and treatment. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:1298–1311.

- Roche SJ, Funk L, Sciascia A. Scapular dyskinesis: the surgeon’s perspective. Shoulder Elbow. 2015;7:289–297.

- Burn MB, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM. Prevalence of scapular dyskinesis in overhead and nonoverhead athletes: a systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4:2325967115627608–2325967115627608

- Jindal M. Delayed presentation of osteochondroma at superior angle of scapula – a case report. J Orthop Case Rep. 2016;6:32–34.

- Britto AVO, Rosenfeld A, Yanaguizawa M. Avaliação por imagem dos elastofibromas da cintura escapular. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2009;49:321–327.

- Lintner D, Noonan TJ, Kibler WB. Injury patterns and biomechanics of the athlete’s shoulder. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27:527–551.

- Kouvalchouk JF. Subscapular crepitus. Orthop Trans. 1985;9:587–588.

- McFarland EG, Tanaka MJ, Papp DF. Examination of the shoulder in the overhead and throwing athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27:553–578.

- Millett PJ, Pacheco IH, Gobezie R, Warner JJP. Management of recalcitrant scapulothoracic bursitis: Endoscopic scapulothoracic bursectomy and scapuloplasty. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;7:200–205.

- Milch H. Partial scapulectomy for snapping of the scapula. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44:1696–1697.

- O’Holleran JD, Millett PJ, Warner JJP. Arthroscopic management of scapulothoracic disorders. In: Miller MD, Cole BD, editors. Textbook of arthroscopy. Ed 3. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. pp. 277–287.

- Tripp BL. Principles of restoring function and sensorimotor control in patients with shoulder dysfunction. Clin Sports Med. 2008;27:507–519.

- Ciullo JV, Jones E. Subscapular bursitis: conservative and endoscopic treatment of “snapping scapula” or “washboard syndrome.” Orthop Trans. 1993;16:740.

- McClusky GM, Bigliani L. Scapulothoracic disorders. In: Andrews JR, Wilk KE, editors. The Athlete’s Shoulder. New York, NY: Churchill Livingston; 1994. pp. 305–316.

- Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic Exercise: Foundation and Techniques. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis; 2002.

- Janda V. Muscles and cervicogenic pain syndromes. In: Grant R, editor. Physical Therapy of the Cervical and Thoracic Spine. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. pp. 153–166.

- Knott M, Voss D. Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1968.

- Lehman GJ, Gilas D, Patel U. An unstable support surface does not increase scapulothoracic stabilizing muscle activity during push up and push up plus exercises. Man Ther. 2008;13:500–506.

- Pavlik A, Ang K, Coghlan J, Bell S. Arthroscopic treatment of painful snapping of the scapula by using a new superior portal. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:608–612.

- Dominguez RH, Gajda R. Total Body Training. East Dundee, Ill: Moving Force Systems; 1982.

- Dintman G, Ward B, Tellez T. Sports Speed. Champaign, Ill: Human Kinetics; 1997.

- Pearse EO, Bruguera J, Massoud SN, Sforza G, Copeland SA, Levy O. Arthroscopic management of the painful snapping scapula. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:755–761.

- Lehtinen JT, Macy JC, Cassinelli E, Warner JJ. The painful scapulothoracic articulation: surgical management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;423:99–105.

- Milch H. Partial scapulectomy for snapping of the scapula. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32-A:561–566.

- Oizumi N, Suenaga N, Minami A. Snapping scapula caused by abnormal angulation of the superior angle of the scapula. J Should Elb Surg. 2004;13:115–118.

- Harper GD, McIlroy S, Bayley JI, Calvert PT. Arthroscopic partial resection of the scapula for snapping scapula: A new technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:53–57.

- Ross AE, Owens BD, DeBerardino TM. Open scapula re-section in beach-chair position for treatment of snapping scapula. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2009;38:249–251.

- Nicholson GP, Duckworth MA. Scapulothoracic bursectomy for snapping scapula syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:80–85.

- Arntz CT, Matsen FA. Partial scapulectomy for disabling scapulothoracic snapping. Orthop Trans. 1990;14:252–253.

- McCluskey GM, III, Bigliani LU. Surgical management of refractory scapulothoracic bursitis. Orthop Trans. 1991;15:801.

- Sisto DJ, Jobe FW. The operative treatment of scapulothoracic bursitis in professional pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14:192–194.

- Fukunaga S, Futani H, Yoshiya S. Endoscopically assisted resection of a scapular osteochondroma causing snapping scapula syndrome. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:37.

- VanRiet RP, Bell SN. Scapulothoracic arthroscopy. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;7:143–146.

- Kuhne M, Boniquit N, Ghodadra N, Romeo AA, Provencher MT. The snapping scapula: diagnosis and treatment. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:1298–1311.

- Blønd Lars, Rechter Simone. Arthroscopir treatment for snapping scapula: a prospective case series. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013 Jan 5

- Lien SB, Shen PH, Lee CH, Lin LC. effect of endoscopic bursectomy with mini-open partial scapulectomy on snapping scapula syndrome. J Surg Res. 2008;150:236–242.