Sneddon syndrome

Sneddon syndrome also called Ehrmann-Sneddon syndrome, is a rare progressive condition that affects small- and medium-sized blood vessels. Sneddon syndrome is primarily characterized by livedo reticularis (net-like patterns of discoloration on the skin) and neurological abnormalities 1. Sneddon syndrome symptoms may include transient ischemic attacks (mini-strokes) and strokes; headache; dizziness; abnormally high blood pressure (hypertension); and heart disease 2. Reduced blood flow to the brain may cause reduced intellectual ability, memory loss, personality changes, and/or other neurological symptoms. The combination of stroke symptoms and livedo reticularis differentiates Sneddon syndrome from other disorders.

The cause of Sneddon syndrome is often unknown, but it is sometimes associated with an autoimmune disease. Most cases are sporadic but some familial cases with autosomal dominant inheritance have been reported.

Sneddon syndrome was first described a separate clinical entity in the medical literature by Dr. Sneddon and colleagues in 1965 1. Since that time, significant debate has existed as to whether Sneddon syndrome is a distinct disorder, part of a spectrum of disorders, or a subtype of antiphospholipid syndrome. Some researchers believe that Sneddon syndrome should be separated into primary and secondary cases depending on whether an underlying cause has been identified (primary versus idiopathic), while others suggest a classification based on whether certain symptoms of autoimmune disease are present or not (aPL-positive versus aPL negative) 1. Primary Sneddon syndrome would denote cases where there was no known cause (idiopathic); secondary Sneddon syndrome would denote cases that are believed to occur secondary to another disorder or thrombophilic state. Some researchers believe that Sneddon syndrome should be differentiated by whether antiphospholipid antibodies are present (aPL-positive) or absent (aPL-negative), others discuss autoimmune/inflammatory etiopathogenesis versus thrombophilia.

Sneddon syndrome has an estimated annual incidence of approximately one out of 250,000 individuals in the general population 2. Sneddon syndrome has been reported much more often in females than in males, especially young women under the age of 45 1. Almost 80% of the patients are women with a median age of diagnosis at 40 years. Symptoms usually begin in early to middle adulthood, but can occur at any age including childhood. It does occur occasionally in girls as young as 10 years old 3.

Sneddon syndrome treatment usually involves anticoagulation (blood-thinning) with warfarin, and/or the use of other medications 2.

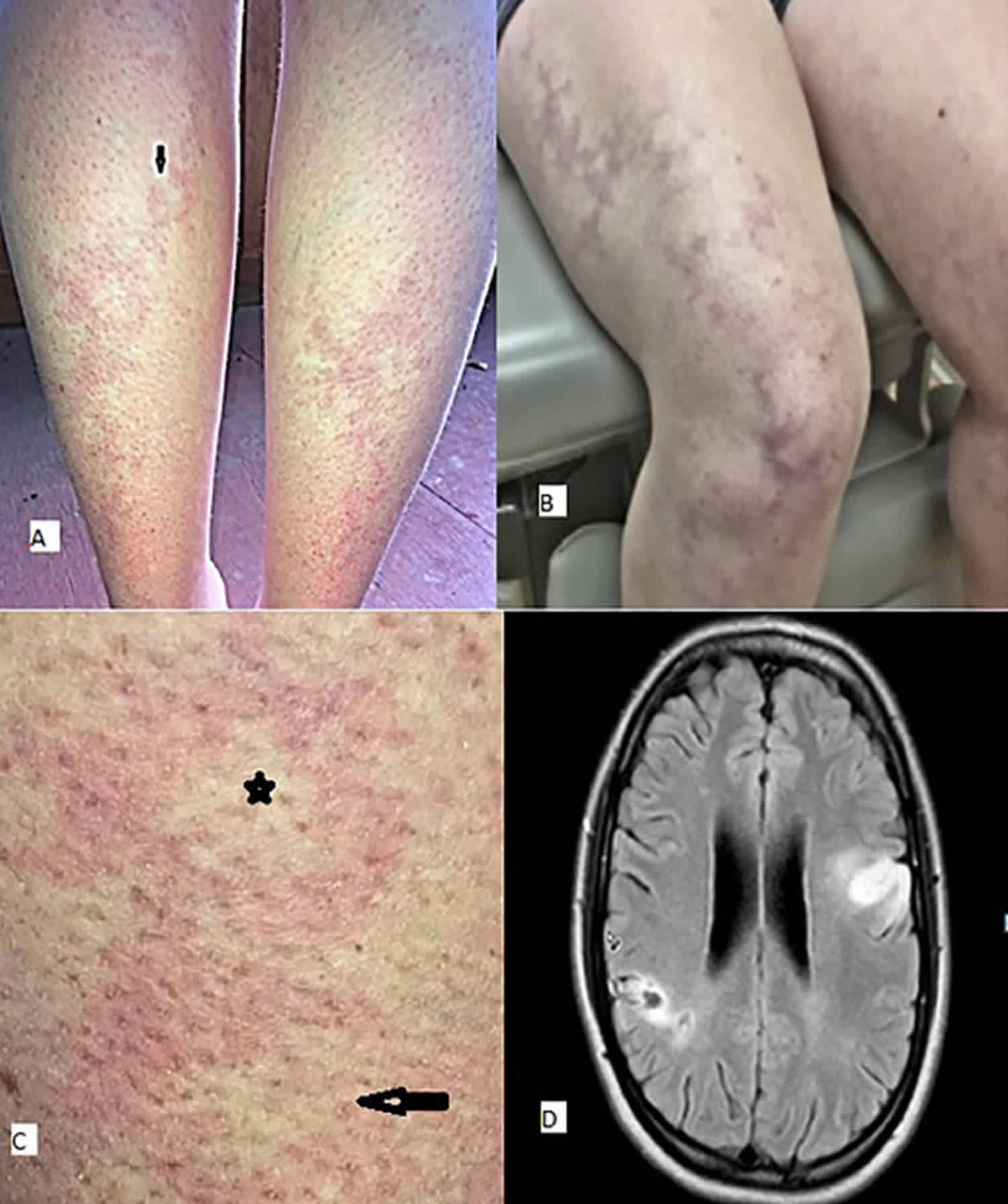

Figure 1. Livedo reticularis

Footnote: Clinical photograph demonstrating widespread livedo racemosa with persistant, violaceous, mottled discoloration of the skin.

[Source 4 ]Sneddon syndrome classification

Sneddon syndrome is classified as antiphospholipid negative (aPL-negative) or antiphospholipid positive (aPL-positive), based on the presence of any of 3 antiphospholipid antibodies: anticardiolipin, lupus anticoagulant, and anti-beta 2-glycoprotein 1 5.

Sneddon syndrome can also be classified as primary (idiopathic) or secondary to an identified thrombophilia or autoimmune disease, such as lupus erythematosus 6. Sneddon syndrome is also occasionally classified as a vasculitis.

Sneddon syndrome causes

The underlying cause of Sneddon syndrome is not well-understood. About 50% of cases are idiopathic (of unknown cause). Possible immunological, environmental, genetic, and/or other factors are under investigation as potential causes of Sneddon syndrome. In some cases, it is associated with autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome, Behçet disease, or mixed connective tissue disease 2.

Genetic factors are thought to play a role in the development of Sneddon syndrome, as familial cases have been reported 2. In one family, a mutation in the CECR1 gene was identified as the cause of Sneddon syndrome 7. Mutations in this gene have been found to cause adenosine deaminase 2 deficiency, a condition that also causes livedo racemosa (and other symptoms) and has earlier onset than Sneddon syndrome.

The signs and symptoms of Sneddon syndrome are caused by excessive growth of the inner surface of blood vessels (endothelial proliferation), leading to occlusion of the arteries with impaired blood flow and clotting (thrombosis) 2. Clumps of cells may break loose and circulate in the blood stream. The clumps may lodge in an artery and block blood flow (embolism). Tissue loss or damage may occur in areas deprived of blood flow.

Some affected individuals have high levels of antiphospholipid antibodies in the blood. Antibodies are part of the body’s immune system and act against invading or foreign microorganisms (e.g., bacteria or viruses). Antiphospholipid antibodies mistakenly recognize phospholipids (part of a cell’s membrane) as foreign and act against them. The significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in approximately 40 to 50 % of patients with Sneddon syndrome is unknown. Some researchers believe that, in familial cases of Sneddon syndrome, affected individuals may have a genetic predisposition to the production of these antibodies. The presence of antiphospholipid antibodies in some cases suggests a possible association with an autoimmune disorder called antiphospholipid syndrome. However, the specific relationship between these two disorders is unknown.

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune disorder, a disorder that occurs when the body’s immune system mistakenly targets healthy tissue. Less often, Sneddon syndrome can be associated with other autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Behcet’s disease, or mixed connective tissue disease.

It is unknown whether individuals with Sneddon syndrome with antiphospholipid antibodies have a different disorder from individuals with Sneddon syndrome without antiphospholipid antibodies. In 2003, researchers determined several members of one family who had Sneddon syndrome without antiphospholipid antibodies had an alteration (mutation) in the CERC1 gene.

Sneddon syndrome symptoms

Sneddon syndrome is a slowly progressive disorder of small- and medium-sized arteries, which are the blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart. The disorder is characterized by blockages (occlusions) of the arteries that cause a reduction of blood flow to the brain and to the skin. Associated symptoms vary from one person to another based, in part, upon the specific arteries that are affected. An irregular, net-like pattern of bluish skin discoloration surrounding areas of normal-appearing skin (livedo reticularis) is characteristic of this disorder. The arms and legs are most often affected as well as the trunk, buttocks, and hands and feet. Livedo reticularis is worsened by cold and pregnancy. In the European medical literature, the term livedo reticularis is used to describe the skin changes of the extremities only that disappear when the skin is warmed. Livedo racemosa is used to describe skin changes that involve also the buttocks and the trunk and do not disappear with warm temperatures. These two dermatologic conditions are separated because livedo reticularis is much more frequent, but the association with strokes exists for livedo racemosa only.

Generally, livedo reticularis develops before the neurological symptoms by as much as 10 years, although sometimes the onset of skin symptoms may occur at approximately the same time. Only rarely, do the skin symptoms occur after the neurological symptoms. Painfully cold fingers and toes caused by dilation or constriction of small vessels in response to cold (Raynaud’s phenomenon) may also occur. Blues discoloration of the hands and feet due to the lack of blood flow (acrocyanosis) has also been reported.

Recurrent episodes of mini-strokes (transient ischemic attacks) or strokes (cerebrovascular accidents) are a common finding of Sneddon syndrome. Less frequently, microbleeds and intracerebral hemorrhages also occur in Sneddon syndrome. The associated neurological symptoms vary depending upon the location of arterial blockages or bleedings. These symptoms may include difficulty concentrating, memory loss, confusion, personality changes, impaired vision, and weakness of one side of the body (hemiparesis). Sneddon syndrome may cause progressive reduction of mental and cognitive function, potentially resulting in dementia. Aphasia, which is defined as a communication disorder that impairs the ability to process language including impairing the ability to speak or understand others, is also common. Less often, seizures, muscle pain and stiffness, and abnormal movements caused by repetitive, jerky muscle contractions (chorea) may also occur.

Generalized symptoms (e.g., headaches and migraines and/or dizziness or vertigo) may be present for several years before neurological symptoms and/or visible skin discoloration appears. High blood pressure (hypertension) is also common.

Heart murmurs, heart disease resulting from reduced blood flow to heart tissue (ischemic heart disease), or thickening of the valves between the chambers of the heart (valvular stenosis) have also been diagnosed in people with Sneddon syndrome and may be associated with rheumatic heart disease or endocarditis. In rare cases, impairment of the kidneys may occur.

Dermatological manifestations

Sneddon syndrome is characterized by livedo racemosa, which often precedes the onset of recurrent strokes by over 10 years 6.

- Livedo racemosa is due to persistent obstruction of peripheral blood flow due to the occlusion of small or medium-sized arteries 8.

- It presents as a branching, net-like pattern of dusky erythematous or violaceous broken circles.

- Unlike livedo reticularis, skin discolouration remains unchanged with warming, although it is more prominent during cold exposure and pregnancy 6.

- Livedo racemosa initially affects the buttocks and lower back.

- It gradually progresses to involve the dorsal aspects of the thighs and arms.

- It rarely affects the face, hands, or feet.

- Lesions are painless and are not associated with oedema, ulceration, or pruritus 6.

Other dermatological manifestations associated with Sneddon syndrome include:

- Acrocyanosis

- Raynaud phenomenon

- Angiomas

- Circumscribed ulcers

- Annular atrophic lichen planus 6.

Neurological manifestations

Neurological manifestations associated with Sneddon syndrome generally present in three stages.

- There may be prodromal symptoms such as vertigo, dizziness, and headaches 6.

- In the second stage, patients experience recurrent episodes of strokes or transient ischemic attacks due to ischemia in the zones perfused by the middle or posterior cerebral arteries 9. Typical symptoms include aphasia, visual field defects, hemiparesis, and sensory disturbances 5.

- The third stage is characterized by significant cognitive decline and early-onset dementia, due to the cumulative effect of multiple cerebral infarcts. Cognitive dysfunction, affecting memory, attention, and visuospatial domains, and psychiatric disturbances, such as depression, are reported in approximately 77% of patients with Sneddon syndrome 10.

Sneddon syndrome complications

Cerebrovascular complications of Sneddon syndrome include 6:

- Ischemic stroke

- Hemorrhagic stroke (rare)

- Seizures

- Movement disorder (rare), such as chorea or cerebellar tremor.

Cardiovascular complications of Sneddon syndrome may include:

- Mitral or aortic valvulopathy

- Libman-Sacks endocarditis

- Systolic labile hypertension.

Ophthalmological complications of Sneddon syndrome may include:

- Optic disc microaneurysm

- Macular edema

- Retinal artery branch obstruction.

Renal complications are rare, and include:

- Impaired creatinine clearance

- Renal artery thrombosis.

Sneddon syndrome diagnosis

The diagnosis of Sneddon syndrome is usually suggested by the combination the pattern of skin discoloration called livedo reticularis (livedo racemosa) and neurological symptoms, particularly unexplained stroke in young individuals 6. Diagnosis of cerebrovascular damage is confirmed when imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) reveal lesions (infarcts) in the brain. History of transient ischaemic attacks or stroke or evidence of these on imaging can support the diagnosis 5.

Patients with a suspected diagnosis of Sneddon syndrome should undergo several investigations, including blood tests screening for autoimmune disease and coagulopathies, cerebral MRI, cardiovascular assessment, and skin biopsy 6.

Surgical removal and microscopic study of tissue samples (skin biopsy) may confirm the progressive arterial disease (arteriopathy) characteristic of Sneddon syndrome demonstrating occlusion of the vessel lumina with no vasculitis. On deep skin biopsy, histopathology demonstrates a non-inflammatory thrombotic vasculopathy involving small and medium-sized dermal arteries 5. Typically, there is are signs of vasculopathy at different stages. Sensitivity increases with the number of deep skin biopsies: 27% sensitivity with one, 53% with two, and 80% with three biopsies 5.

Blood tests should screen for lupus anticoagulant, immunoglobulin IgG and possibly IgM anti-cardiolipinantibodies, anti-nuclear and anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibodies, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, VDRL, cryoglobulins, circulating immune complexes, antithrombin-III, protein C, or protein S 11. Blood tests may reveal the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies in some affected individuals.

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is usually normal 5.

Lesions identified by MRI tend to be small, multifocal, and often located in the periventricular deep white matter or pons. In up to 75% of patients with Sneddon syndrome, cerebral angiography is abnormal 5.

Sneddon syndrome treatment

The optimal management of Sneddon syndrome has not been established, and controlled trials have not yet been performed 3. Currently, the most widely accepted treatment is anticoagulation with warfarin. Some suggest that antiphospholipid antibodies negative (aPL-negative) patients should follow a less aggressive approach consisting of antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, while others recommend warfarin with a higher international normalized ratio target 2.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have been suggested to reduce endothelial proliferation (growth of the inside lining of the vessels), and prostaglandin to improve blood flow and gas exchange in small vessels (microvascular perfusion) 2. Abstaining from smoking and abstaining from using estrogen oral contraceptives may prevent or decrease the severity of neurological symptoms 3.

While the use of immunosuppressive therapy appears generally ineffective, there are data indicating that rituximab may be effective in antiphospholipid antibodies positive (aPL-positive) patients 2.

Additional research exploring the underlying causes of Sneddon syndrome may identify treatment options based on the cause in each affected person 3.

Sneddon syndrome life expectancy

While we are not aware of statistics regarding the life expectancy of people with Sneddon syndrome, studies have estimated the six year mortality rate to be 9.5% 12.

Sneddon syndrome prognosis

Sneddon syndrome is a chronic, progressive disease often resulting in cognitive decline and early-onset dementia, due to the cumulative effect of multiple cerebral infarcts 2. The exact neurological symptoms vary, depending upon the location of arterial blockages 1. However, the condition often causes progressive reduction of mental and cognitive function. Dementia ultimately occurs in many patients, resulting in early retirement 2. Aphasia, the loss of ability to express or understand speech, is also common 1.

References- Sneddon Syndrome. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/sneddon-syndrome

- Sneddon syndrome. https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?lng=en&Expert=820

- Wu, S., Xu, Z. & Liang, H. Sneddon’s syndrome: a comprehensive review of the literature. Orphanet J Rare Dis 9, 215 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-014-0215-4

- Timoney I, Flynn A, Leonard N, et al. Livedo racemosa: a cutaneous manifestation of Sneddon’s syndrome. BMJ Case Reports CP 2019;12:e232670

- Wu S, Xu Z, Liang H. Sneddon’s syndrome: a comprehensive review of the literature. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:215. Published 2014 Dec 31. doi:10.1186/s13023-014-0215-4

- Samanta D, Cobb S, Arya K. Sneddon Syndrome: A Comprehensive Overview. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(8):2098-2108. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.05.013

- Kniffin CL. Sneddon syndrome. OMIM. August 4, 2014 https://www.omim.org/entry/182410

- Orac A, Artenie A, Toader MP, et al. Sneddon syndrome: rare disease or under diagnosed clinical entity? Review of the literature related to a clinical case. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2014;118(3):654-660.

- Boesch SM, Plörer AL, Auer AJ, et al. The natural course of Sneddon syndrome: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings in a prospective six year observation study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74: 542–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.4.542

- Wright RA, Kokmen E. Gradually progressive dementia without discrete cerebrovascular events in a patient with Sneddon’s syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 1999; 74: 57–61. doi: 10.4065/74.1.57

- Stockhammer G, Felber SR, Zelger B, Sepp N, Birbamer GG, Fritsch PO, Aichner FT. Sneddon’s syndrome: diagnosis by skin biopsy and MRI in 17 patients. Stroke. 1993;24:685–690. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.5.685

- Bayrakli F, Erkek E, Kurtuncu M, Ozgen S. Intraventricular hemorrhage as an unusual presenting form of Sneddon syndrome. World Neurosurg. 2010;73(4):411-413. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2010.01.010