Spondylolisthesis

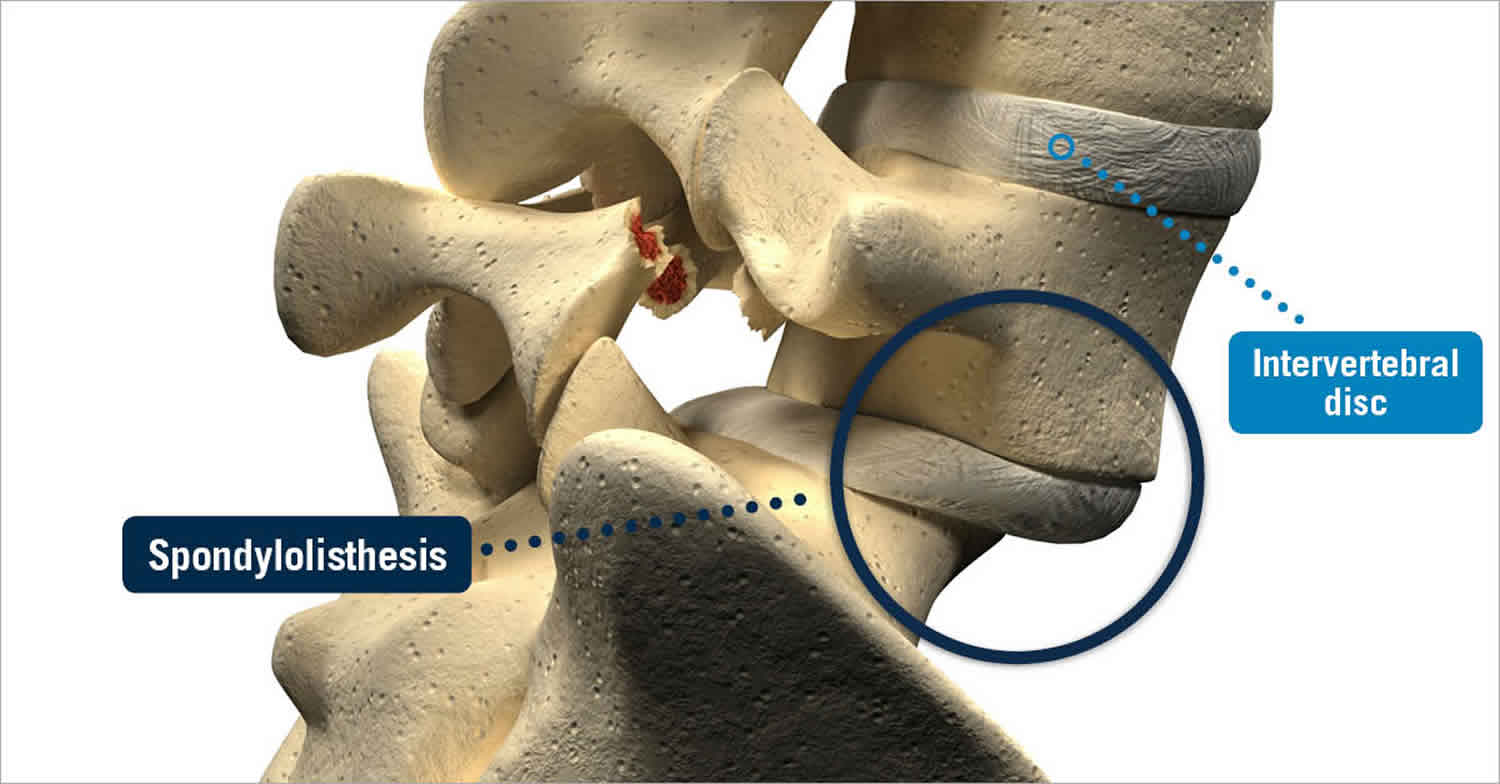

Spondylolisthesis is a problem in which one of the bones in your spine — called a vertebra — slips forward (listhesis) over the vertebra (spondylo) below it. The forward subluxation of the vertebral body can cause a decrease in the diameter of the spinal canal (spinal stenosis). The slippage also can result in accelerated degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Furthermore, the subluxation can lead to hypertrophy of the facet joints and ligamentum flavum posteriorly which can result in stenosis of the lateral recess and neural foramina. There also can be traction placed on the exiting nerve roots which commonly affects the exiting nerve root below the pedicle of the vertebral body above the level of the spondylolisthesis. When spondylolisthesis compresses the nerve that sits between the vertebrae it can cause lower back pain, muscle tightness, weakness or stiffness in the legs, and tingling or numbness in the thigh or buttocks.

However, spondylolisthesis may not cause any symptoms for years (if ever) after the slippage has occurred. If you do have symptoms, they may include low back and buttocks pain; numbness, tingling, pain, muscle tightness or weakness in the leg (sciatica); increased sway back; or a limp. These symptoms are usually aggravated by standing, walking and other activities, while rest will provide temporary relief.

Spondylolisthesis most commonly occurs in the lower back (lower lumbar spine) but can also occur in the cervical spine and rarely, except for trauma, in the thoracic spine. Spondylolisthesis most commonly occurs at the L5-S1 level with anterior translation of the L5 vertebral body on the S1 vertebral body 1. The L4-5 level is the second most common location for spondylolisthesis 1.

Spondylolisthesis can be due to congenital (present at birth), acquired or idiopathic (unknown) causes. Spondylolisthesis is graded based on the degree of slippage of one vertebral body on the adjacent vertebral body.

Most spondylolisthesis can be described as either degenerative spondylolisthesis (due to chronic inter-segmental instability involving degenerative disc and facet joints) or isthmic spondylolisthesis (results from defects in the pars interarticularis) (see Figure 6 below).

Degenerative spondylolisthesis usually affect older patients, more frequently involve women and the L4/5 level, and have relatively small slips (<30%) with associated stenosis. In contrast, isthmic spondylolisthesis usually affect patients younger than 50, primarily involves the L5 level, and may have quite severe progression and associated structural abnormalities.

In adults, the main causes of spondylolisthesis are arthritis, osteoporosis and bone fractures or a sudden injury or trauma to the spine.

In children, spondylolisthesis is usually caused by a birth defect or an injury to the lower back.

About 4% to 6% of the U.S. population has spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Most of these people live with the condition for many years without any pain or other symptoms.

Some people with spondylolisthesis feel:

- pain or stiffness in their lower back

- tight muscles, or spasms, in the back of their thighs

- pain, numbness, or tingling in their buttocks, legs, and feet

- weakness in their legs

To diagnose spondylolisthesis, a doctor usually performs a physical examination, and may order an X-ray of your lower back to see if a vertebra is out of place. Sometimes other imaging tests, such as a CT (computed tomography) scan or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan, might be needed.

There are many different approaches to easing the pain associated with spondylolisthesis.

Most people with spondylolisthesis get better with exercises that stretch and strengthen lower back muscles.

If you are diagnosed with spondylolisthesis, there is a range of treatment such as:

- avoiding heavy physical work and exercise

- taking medications, such as pain killers like paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- physiotherapy, such as exercises to improve abdominal muscle tone

- surgery, which usually involves relieving the pressure on your nerves and possibly fusing the affected vertebrae to stop them slipping again

Vertebra anatomy

Your spine is made up of 24 small rectangular-shaped bones, called vertebrae, which are stacked on top of one another. These bones connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

The five vertebrae in the lower back comprise the lumbar spine.

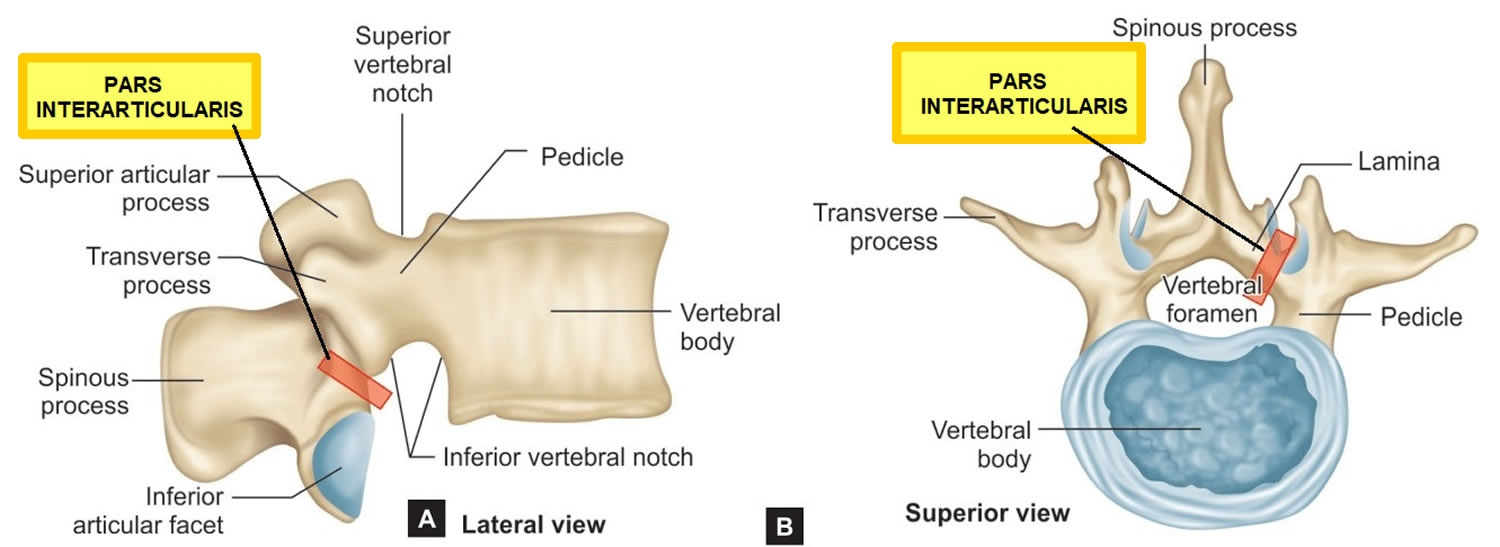

Each individual vertebra has unique features depending on the region in which it is found. Every vertebra, regardless of location, has three basic functional parts: (1) the drum-shaped vertebral body, designed to bear weight and withstand compression or loading; (2) the posterior (backside) arch, made of the lamina, pedicles and facet joints; and (3) the transverse processes, to which muscles attach.

Other parts of your spine include:

Spinal cord and nerves

These “electrical cables” travel through the spinal canal carrying messages between your brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch out from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae.

Facet joints

Between the back of the vertebrae are small joints that provide stability and help to control the movement of the spine. The facet joints work like hinges and run in pairs down the length of the spine on each side.

Intervertebral disks

In between the vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. These disks are flat and round and about a half inch thick. Intervertebral disks cushion the vertebrae and act as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

The vertebral body

The vertebral body is composed of hard cortical bone on the outside and less dense cancellous bone on the inside. The top and bottom of the vertebral body are called the end plates. The intervertebral disc, sandwiched between two vertebral bodies, is attached to the end plates. Changes in the disc may be accompanied by changes in the end plates.

The pedicle is a paired, strong, tubular bony structure made of hard cortical bone on the outside and cancellous bone on the inside. Each pedicle comes out of the side of the vertebral body and projects to the back. Pedicles act as the lateral (side) walls of the bony spinal canal that protects the spinal cord and cauda equina, or nerve roots, in the lumbar region. There is also a space created between the facet joints and pedicles of one vertebral body and the next, called the intervertebral foramen, through which the spinal nerves branch out to the rest of your body.

The lamina are shingle-like plates of bone coming from the pedicles to arch over the nerves and join at the midline. The lamina are shorter than the vertebral bodies so that there is a gap between any two laminae, bridged by soft tissue called the ligamentum flavum. This provides additional protection for the nerves that lie underneath it. Together, the lamina and pedicles form the vertebral arch.

As the lamina come together at the back of the spinal column, they join to form the spinous process, the bony part of the spine that you can feel at the midline when you rub your back. There is an interspinous ligament that runs between the spinous processes of the vertebrae and a supraspinous ligament that runs on top of them from the cervical region to the sacrum.

Each vertebral body has two articular processes at the top and bottom where the lamina and pedicle meet. These articular processes create a joint, called the facet joint, between the stacked vertebral bodies. There is a facet joint on each side of the vertebral body. The facet joint typically lies behind the spinal nerves as they emerge from the central spinal canal. The surfaces of the facet joint are capped with cartilage and the joint is contained in a capsule lined by synovium, much like the knee joint. The two facet joints and the intervertebral disc at each level allow for motion between the vertebral bodies.

The typical vertebral body has two transverse processes, or lateral projections, one on each side. These projections serve as points of attachment for muscles and ligaments in the spine. In the cervical spine, the transverse processes each have a foramen or canal through which the vertebral artery and vein travel. The intertransverse ligaments connect the transverse processes of the vertebrae on each side of the spinal column.

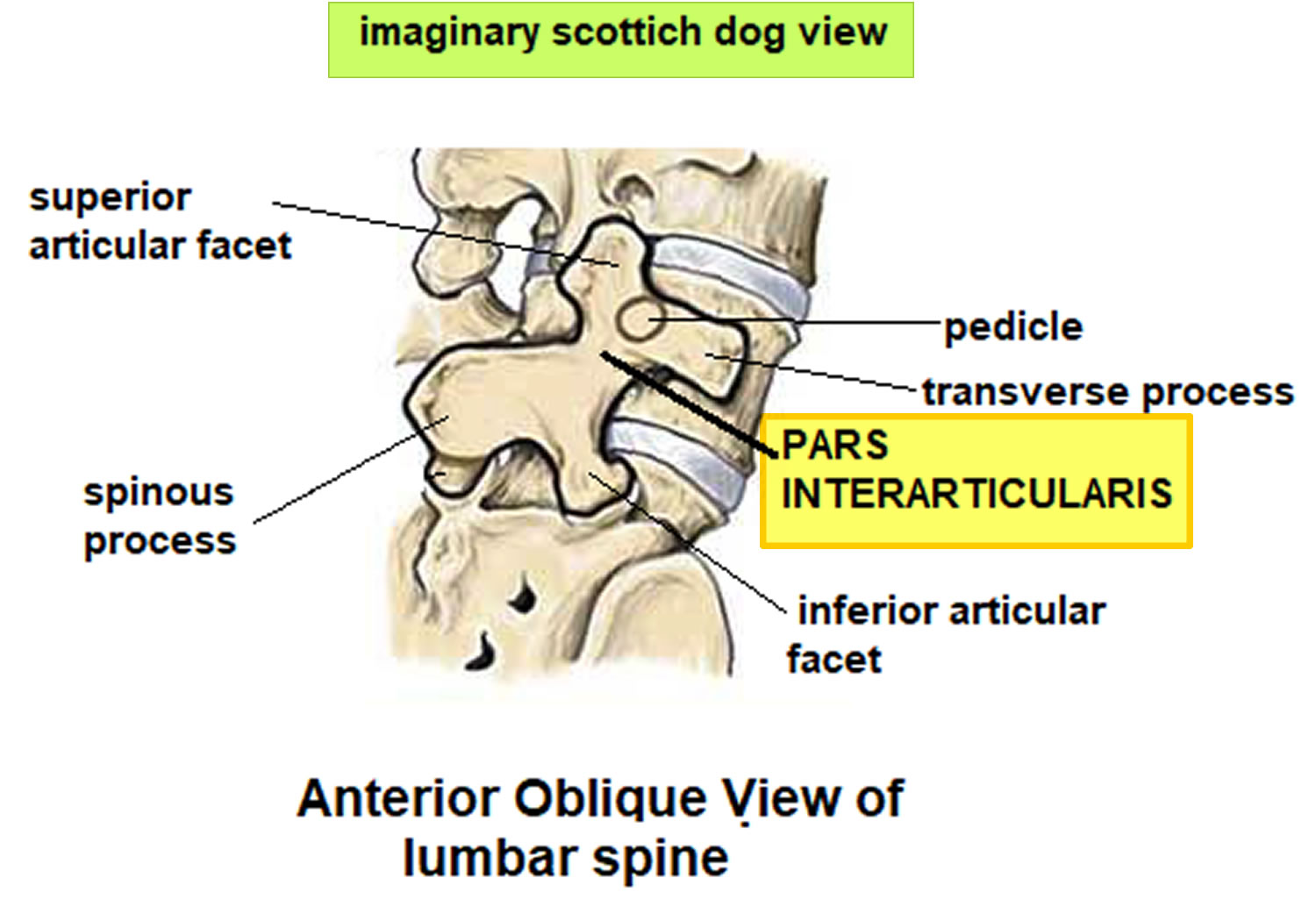

In the lumbar spine, identification of the pars interartcularis is important because it is the site of pathology related to spondylolisthesis, or “slipped vertebra.” This is another paired structure on the back side of the spine and it links the pedicle, transverse process, lamina and articular facets on each side of the vertebrae.

Figure 1. Lumbar vertrebrum (looking from above)

Figure 2. Lumbar vertebrae anatomy (looking from behind and from the side)

Figure 3. Pars interarticularis

Figure 4. Pars interarticularis oblique view showing the imaginary “Scottish dog”

Figure 5. Spinal cord segments

Types of Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis is commonly classified as one of five major causes as described by Wiltse in 1981 2: degenerative, isthmic, traumatic, dysplastic or pathologic. The two most common types are degenerative and spondylolytic. There are other less common types of spondylolisthesis, such as slippage caused by a recent, severe fracture or a tumor.

Wiltse spondylolisthesis classification 2:

- Type 1 (dysplastic/congenital spondylolisthesis): translation is secondary to an abnormal neural arch

- Type 2 (isthmic spondylolisthesis): translation is secondary to a lesion involving the pars interarticularis

- Type 2A (lytic): secondary to stress fracture, in most cases attributed to repeated extension and/or twisting motions

- Type 2B (elongated pars): result of multiple injury/healing events leading to elongation of the pars

- Type 2C (acute pars fracture): secondary to a single event and is rare

- Type 3 (degenerative spondylolisthesis): result of chronic instability and intersegmental degenerative changes

- Type 4 (post-traumatic spondylolisthesis): fracture in a region other than the pars leading to slippage.

- Type 5 (pathological spondylolisthesis): diffuse or local disease compromising the usual structural integrity that prevents slippage

- Type 6 (iatrogenic spondylolisthesis)

Typically when reporting studies with spondylolisthesis the Wiltse type is merely stated without referring to its number, whereas the grade of spondylolisthesis is explicitly stated: e.g. “Grade 1 degenerative spondylolisthesis of L5 on S1” rather than “Grade 1, Type III spondylolisthesis”.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis

Degenerative spondylolisthesis occurs from degenerative changes in the spine without any defect in the pars interarticularis and is usually related to combined facet joint and disc degeneration leading to instability and forward movement of one vertebral body in relation to the adjacent vertebral body.

As you age, general wear and tear causes changes in the spine commonly known as spondylosis or osteoarthritis of the spine. Intervertebral disks begin to dry out and weaken. They lose height, become stiff, and begin to bulge. This disk degeneration is the start to both arthritis and degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis predominately occurs in adults and is more common in females than males with increased risk in the obese 3.

As arthritis develops, it weakens the joints and ligaments that hold your vertebrae in the proper position. The ligament along the back of your spine (ligamentum flavum) may begin to buckle. One of the vertebrae on either side of a worn, flattened disk can loosen and move forward over the vertebra below it.

This slippage can narrow the spinal canal and put pressure on the spinal cord. This narrowing of the spinal canal is called spinal stenosis and is a common problem in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Women are more likely than men to have degenerative spondylolisthesis, and it is more common in patients who are older than 50. A higher incidence has been noted in the African-American population.

Spondylolytic spondylolisthesis

One of the bones in your lower back can break and this can cause a vertebra to slip forward. The break most often occurs in the area of your lumbar spine called the pars interarticularis, commonly known as spondylolysis or pars interarticularis defect, pars defect or pars fracture.

In most cases of spondylolytic spondylolisthesis, the pars fracture occurs during adolescence and goes unnoticed until adulthood. The normal disk degeneration that occurs in adulthood can then stress the pars fracture and cause the vertebra to slip forward. This type of spondylolisthesis is most often seen in middle-aged men.

Because a pars fracture causes the front (vertebra) and back (lamina) parts of the spinal bone to disconnect, only the front part slips forward. This means that narrowing of the spinal canal is less likely than in other kinds of spondylolisthesis, such as degenerative spondylolisthesis in which the entire spinal bone slips forward.

Isthmic spondylolisthesis

Isthmic spondylolisthesis results from defects or instability of unilateral or bilateral pars interarticularis 4. The cause of isthmic spondylolisthesis is undetermined, but a possible cause includes microtrauma in adolescence related to sports such as wrestling, football, and gymnastics where repeated lumbar extension occurs.

The pars interarticularis, or pars, is the bony structure which connects the lamina, pedicle, and transverse processes of the vertebral bodies. Importantly, the facet joints of the superior and inferior vertebrae also are connected by the pars. Thus, a defect in this structure would effectively “disconnect” the vertebral body above from the vertebral body below. This disconnection allows the anterior subluxation seen in spondylolisthesis. Many biomechanical studies indicate that the pars is subjected to the greatest force of any structure in the lumbar spine; therefore, it is susceptible to stress fractures which may heal and fracture repeatedly over time. These injuries can induce non-healing fractures or an elongated pars without a defect which likely indicates repeated fracture healing. Pars fractures are believed to be the result of repetitive motion. Thus, risks associated with pars defects include activities associated with repetitive flexion/extension, axial loading, and rotational loading (i.e., golfers, baseball and football players, gymnasts).

The incidence of isthmic spondylolisthesis is generally reported as between 4% to 8% of the general population 4. Isthmic spondylolisthesis is more common in the adolescent and young adult population but may go unrecognized until symptoms develop in adulthood. There is a higher prevalence of isthmic spondylolisthesis in males 3. Current estimates for prevalence are 6-7% for isthmic spondylolisthesis by the age of 18 years and up to 18% of adult patients undergoing MRI of the lumbar spine.

An interesting cross-sectional study utilizing the Framingham Heart Study participant of 3529 patients showed that 20% of patients with CT finding of bilateral pars defect showed no evidence of spondylolistheisis 5. In addition, this cross-sectional study showed that the incidence of spondylolisthesis increases significantly from the fifth decade of life to the eighth decade of life 6.

Subclasses of isthmic spondylolisthesis are subtype A (stress fractures of the pars), subtype B (elongation of the pars without overt fracture), subtype C (acute fracture of the pars).

Many cases of isthmic spondylolisthesis are asymptomatic. However, the most common symptom of presentation is low back pain, which may be mechanical in nature 6. Patients also can present with neurogenic claudication symptomatology such as back and leg pain and discomfort associated with walking. These symptoms need to be differentiated from vascular claudication, which is exacerbated by ambulation and gets better with rest. Other patients can present with symptoms of specific dermatome of lumbar radiculopathy depending on the compressed nerve root and the amount of subluxation or stenosis. Physical examination can show different degrees of findings ranging from normal to paraplegia. However, the most common findings are depressed deep tendon reflexes, positive straight leg signs, and diminished sensations. Some patients can have specific pain-related weakness of lower extremities. Usually, patients with chronic isthmic spondylolisthesis do not present with significant motor weakness; however, acute isthmic spondylolisthesis can present with paralysis and loss of bowel and bladder function.

Isthmic spondylolisthesis with low back pain should initially be managed conservatively. NSAIDs, muscle relaxers, physical therapy, and epidural steroid injections are some of the conservative options. Should the back pain persist despite conservative management, or if the severity is such that quality of life is significantly affected, then referral to a specialist for evaluation is indicated. When the presentation consists of symptoms of neurogenic claudication or radiculopathy, then imaging of the neural elements of the lumbar spine is indicated along with referral to a specialist. Surgical treatment options consist of decompression of the neural elements alone versus decompression with internal fixation for bony fusion to prevent further subluxation 7. In addition, for patients who present with acute symptoms due to trauma or malignancies, emergent surgical referrals are indicated 8, 9.

Traumatic spondylolisthesis

Traumatic spondylolisthesis occurs after fractures of the pars interarticularis or the facet joint structure and is most commonly seen after high energy trauma. This rare injury arises from complex trauma and high-energy mechanisms resulting in pathoanatomical changes at the intervertebral articulations. Traumatic spondylolisthesis is encountered in a car crash or job-related accidents in factories where the lumbar spine is hit by a heavy object 10. Males are predominantly involved with an age ranging from 35 to 55 years old.

A high-energy trauma is necessary to achieve this injury type. A lumbar transverse process fracture is a hint for the clinician to look for a possible traumatic spondylolisthesis 10. The mechanism advocated in the literature for spondylolisthesis with bilateral facet dislocation is a hyperflexion associated with varying degrees of distraction. The inferior articular facet of the superior vertebra is displaced and “locked “anterior to the superior articular facet of the vertebra below.

Hyperflexion alone can produce either pure dislocation or fracture-dislocation in the lumbar spine. However, facet joint disruption also can be unilateral. When it occurs, a rotational component is added to the flexion-distraction mechanism. The superior and inferior articular processes of the joint are displaced relative to each other due to injuries of the above-mentioned ligaments. This injury type tends to occur at the junction of rigid and mobile parts of the spine such as the thoracolumbar or lombo-sacral junction. The “seatbelt injury” is the classical example which occurs with improper use of a three-point seat belt. The lap belt holds the lower part of the spine immobile while the upper segment is hyper-flexed and moves anteriorly, resulting in facet joint disruption. It has been evoked particularly in L4, L5, and L5-S1 listhesis 11, 12.

Dysplastic spondylolisthesis

Dysplastic spondylolisthesis is congenital (present at birth) and secondary to variation in the orientation of the facet joints to an abnormal alignment that occurs mainly in young patients and typically involves L5-S1 13. In dysplastic spondylolisthesis, the facet joints are more sagittally oriented than the typical coronal orientation.

Dysplastic spondylolisthesis is more common in the pediatric population with females more commonly affected than males 3. The estimated prevalence of scoliosis in the adolescent population is 0.47–5.2% 14, whereas it is 18–48% in young patients with lumbar spondylolisthesis 15, suggesting that spondylolisthesis may induce scoliosis by some mechanism. From literature, patients with dysplastic spondylolisthesis appear to have a higher rate of scoliosis than patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis 16, suggesting that, in addition to the sagittal plane abnormality, dysplastic spondylolisthesis patients are prone to coronal plane abnormality. Furthermore, dysplastic spondylolisthesis often leads to lumbosacral kyphosis and abnormal spino-pelvis alignment 17.

Pathologic spondylolisthesis

Pathologic spondylolisthesis can be from systemic causes such as bone or connective tissue disorders or a focal process including infection, neoplasm or iatrogenic origin. Additional risk factors for spondylolisthesis include a first-degree relative with spondylolisthesis, scoliosis or occult spinal bifida at the S1 level.

Subclasses of pathologic spondylolisthesis are subtype A (systemic causes) and subtype B (focal processes).

Figure 6. Spondylolisthesis types

Spondylosis vs Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolysis is a crack or stress fracture that develops through the pars interarticularis, which is a small, thin portion of the vertebra that connects the upper and lower facet joints. Spondylolysis can occur in people of all ages but, because their spines are still developing, children and adolescents are most susceptible. The injury most often occurs in children and adolescents who participate in sports that involve repeated stress on the lower back, such as gymnastics, football, and weight lifting.

The pars interarticularis is the weakest portion of the vertebra. For this reason, it is the area most vulnerable to injury from the repetitive stress and overuse that characterize many sports.

Most commonly, this fracture occurs in the fifth vertebra of the lumbar (lower) spine, although it sometimes occurs in the fourth lumbar vertebra. Fracture can occur on one side or both sides of the bone.

Many times, patients with spondylolysis will also have some degree of spondylolisthesis.

In some spondylolysis cases, the stress fracture weakens the bone so much that it is unable to maintain its proper position in the spine and the vertebra starts to shift or slip out of place. This condition is called spondylolisthesis. In spondylolisthesis, the fractured pars interarticularis separates, allowing the injured vertebra to shift or slip forward on the vertebra directly below it. In children and adolescents, this slippage most often occurs during periods of rapid growth—such as an adolescent growth spurt.

In many cases, patients with spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis do not have any obvious symptoms. The conditions may not even be discovered until an x-ray is taken for an unrelated injury or condition.

For most patients with spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis, back pain and other symptoms will improve with conservative treatment. This always begins with a period of rest from sports and other strenuous activities.

Patients who have persistent back pain or severe slippage of a vertebra (spondylolisthesis), however, may need surgery to relieve their symptoms and allow a return to sports and activities.

Figure 7. Spondylosis vs Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis causes

Spondylolisthesis may be caused by:

- A congenital disorder of the spine due to failure of the ‘pars interarticularis’ to form, essentially leading to mobile facet joints.

- A result of trauma causing a fracture or tear in the facet joints or ligaments, or

- Simply a degenerative condition due to wear and tear of the joints and ligaments.

Overuse

Both spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are more likely to occur in young people who participate in sports that require frequent overstretching (hyperextension) of the lumbar spine—such as gymnastics, football, and weight lifting. Over time, this type of overuse can weaken the pars interarticularis, leading to fracture and/or slippage of a vertebra.

Genetics

Doctors believe that some people may be born with vertebral bone that is thinner than normal—and this may make them more vulnerable to fractures.

The severity of spondylolisthesis is graded according to the extent of movement of one vertebra on the adjacent vertebra.

Spondylolisthesis grading

A commonly adopted method of grading the severity of spondylolisthesis is the Meyerding classification. It divides the superior endplate of the vertebra below into 4 quarters. The grade depends on the location of the posteroinferior corner of the vertebra above. The grading system is named after its inventor Henry W Meyerding, who was an American orthopedic surgeon at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. He proposed the classification in an article in 1932 18.

This classification was originally developed for anterolistheses but can be adapted for retrolistheses, and some publications have done so 19.

- Spondylolisthesis grade 1: 0-25% displacement of the vertebral body. Grade 1 spondylolisthesis accounts for 75% of all cases.

- Spondylolisthesis grade 2: 26-50% displacement of the vertebral body.

- Spondylolisthesis grade 3: 51-75% displacement of the vertebral body.

- Spondylolisthesis grade 4: 76-100% displacement of the vertebral body.

- Spondylolisthesis grade 5 (spondyloptosis): >100% displacement of the vertebral body.

Pediatric patients are more likely to increase spondylolisthesis grade when going through puberty. Older patients with lower grade 1 or 2 spondylolisthesis are less likely to progress to higher grades over time.

Other doctors simply describe spondylolisthesis as either low grade or high grade, depending upon the amount of slippage. A high-grade slip occurs when more than 50 percent of the width of the fractured vertebra slips forward on the vertebra below it. Patients with high-grade slips are more likely to experience significant pain and nerve injury and to need surgery to relieve their symptoms.

Figure 8. Spondylolisthesis grading

Figure 9. Spondylolisthesis grade 1 (X-ray demonstrates spondylolysis [blue arrow] with grade 1 spondylolisthesis [red arrow])

Figure 10. Spondylolisthesis grade 2

Spondylolisthesis symptoms

Patients with spondylolisthesis may remain asymptomatic throughout their life and be diagnosed incidentally through x-rays of the lumbar region. Studies have shown that 5-10% of patients seeing a spine specialist for low back pain will have either a spondylolysis or isthmic spondylolisthesis. However, because isthmic spondylolisthesis is not always painful, the presence of a crack (spondylolysis) and slip (spondylolisthesis) on the X-ray image does not mean that this is the source of your symptoms.

Patients typically have intermittent and localized low back pain for lumbar spondylolisthesis and localized neck pain for cervical spondylolisthesis. The pain is exacerbated by flexing and extending at the affected segment as this can cause mechanic pain from motion. Pain may be exacerbated by direct palpation of the affected segment. Pain can also be radicular in nature as the exiting nerve roots are compressed due to the narrowing of nerve foramina as one vertebra slips on the adjacent vertebrae, the traversing nerve root (root to the level below) can also be impinged through associated lateral recess narrowing, disc protrusion, or central stenosis. Pain can sometimes be improved in a positional manner such as laying supine. This improvement is due to the instability of the spondylolisthesis that reduces with supine posture thus relieving the pressure on the bony elements as well as opening the spinal canal or neural foramen. Other symptoms associated with lumbar spondylolisthesis include buttock pain, numbness or weakness in the leg(s), difficulty walking and rarely loss of bowel or bladder control.

When symptoms do occur, the most common symptom is lower back pain. This pain may:

- Feel similar to a muscle strain

- Radiate to the buttocks and back of the thighs

- Worsen with activity and improve with rest

In patients with spondylolisthesis, muscle spasms may lead to additional signs and symptoms, including:

- Back stiffness

- Tight hamstrings (the muscles in the back of the thigh)

- Difficulty standing and walking

Spondylolisthesis patients who have severe or high-grade slips may have tingling, numbness, or weakness in one or both legs. These symptoms result from pressure on the spinal nerve root as it exits the spinal canal near the fracture.

A variety of symptoms may occur in lumbar spondylolisthesis and are depend on the degree of lumbar canal stenosis associated. These include:

- Lower back pain – Chronic low back pain radiating to the hips and buttocks may be present. This may be worsened with any back movements.

- Sciatica – Stenosis in the lateral (side) regions of the lumbar canal may result in pressure on the exiting nerve roots. The nerve roots supply power and sensation to the legs and severe radicular pain (pain shooting into the leg) may occur in a specific nerve distribution. Numbness and tingling may also occur in the same region.

- Neurogenic claudication – This is pain running down both legs that get worse with walking and limits the distance you can walk. It is usually a cramp-like pain but occasionally may be burning in sensation. It is due to central lumbar canal stenosis that causes pressure on the cauda equina as you move.

- Cauda equina syndrome – Persistent severe pressure on the cauda equina may result in cauda equina syndrome. This includes:

- Numbness around the bottom and anus

- Impotence or sexual dysfunction

- Loss of bowel or bladder control

Symptoms of degenerative spondylolisthesis

Patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis often visit the doctor’s office once the slippage has begun to put pressure on the spinal nerves. Although the doctor may find arthritis in the spine, the symptoms of degenerative spondylolisthesis are typically the same as symptoms of spinal stenosis. For example, degenerative spondylolisthesis patients often develop leg and/or lower back pain. The most common symptoms in the legs include a feeling of vague weakness associated with prolonged standing or walking.

Leg symptoms may be accompanied by numbness, tingling, and/or pain that is often affected by posture. Forward bending or sitting often relieves the symptoms because it opens up space in the spinal canal. Standing or walking often increases symptoms.

Symptoms of spondylolytic spondylolisthesis

Most patients with spondylolytic spondylolisthesis do not have pain and are often surprised to find they have the slippage when they see it in x-rays. They typically visit a doctor with low back pain related to activities. The back pain is sometimes accompanied by leg pain.

Spondylolisthesis diagnosis

Physical Examination

Your doctor will begin by taking a medical history and asking about your child’s general health and symptoms. He or she will want to know if your child participates in sports. Children who participate in sports that place excessive stress on the lower back are more likely to have a diagnosis of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

Your doctor will carefully examine your child’s back and spine, looking for:

- Areas of tenderness

- Limited range of motion

- Muscle spasms

- Muscle weakness

Your doctor will also observe your child’s posture and gait (the way he or she walks). In some cases, tight hamstrings may cause a patient to stand awkwardly or walk with a stiff-legged gait.

Imaging tests will help confirm the diagnosis of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

Imaging Tests

Plain x-rays – these studies provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Your doctor may order x-rays of your child’s lower back from a number of different angles to look for a stress fracture and to view the alignment of the vertebrae.

Dynamic x-rays will be taken in flexion and extension may be performed to document any instability. Plain x-rays do not give any information on nerve root or spinal cord compression but may demonstrate a pars defect.

If x-rays show a “crack” or stress fracture in the pars interarticularis portion of the fourth or fifth lumbar vertebra, it is an indication of spondylolysis.

CT lumbar-spine – this is usually ordered by your doctor for low back pain/radicular symptoms It gives some information on bony alignment and may demonstrate an obvious pars defect. Occasionally it is combined with a myelogram to demonstrate any functional compression/obstruction.

MRI lumbar-spine – this is the gold standard in looking at lumbar spondylolisthesis and to delineate the degree of nerve root or cauda equina compression. It will also give information as to the cause of the spondylolisthesis. MRI studies provide better images of your body’s soft tissues. An MRI can help your doctor determine if there is damage to the intervertebral disks between the vertebrae or if a slipped vertebra is pressing on spinal nerve roots. It can also help your doctor determine if there is injury to the pars before it can be seen on x-ray.

Spondylolisthesis treatment

If your doctor determines that a spondylolisthesis is causing your pain, he or she will usually try nonsurgical treatments first. These treatments may include a short period of rest, anti-inflammatory medications (orally or by injection) to reduce the swelling, analgesic drugs to control the pain, bracing for stabilization, and physical therapy and exercise to improve your strength and flexibility so you can return to a more normal lifestyle. If you are told to rest, follow your doctor’s directions on how long to stay in bed. Generally, if recommended at all, this would be limited to a few days. (Strict bed rest is usually not necessary.) Ask your doctor whether you should continue to work while you are being treated.

Your doctor may also — sometimes with the help of a nurse or physical therapist — begin education and training in performing activities of daily living without placing added stress on your lower back.

If a combination of medication and therapy fails to provide relief, however, your doctor may order additional tests, which will provide greater detail so he/she can plan further treatment.

Nonsurgical treatment

For grade 1 and 2 spondylolisthesis treatment typically begins with conservative therapy including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), heat, light exercise, traction, bracing and/or bed rest. Approximately 10% to 15% of younger patients with low-grade spondylolisthesis will fail conservative treatment and need surgical treatment.

Medication

Analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines may relieve pain.

Steroid injections

Cortisone is a powerful anti-inflammatory. Cortisone injections around the nerves or in the “epidural space” can decrease swelling, as well as pain. It is not recommended to receive these, however, more than three times per year. These injections are more likely to decrease pain and numbness, but not weakness of the legs.

Spondylolisthesis exercises

Specific exercises can help improve flexibility, stretch tight hamstring muscles, and strengthen muscles in the back and abdomen.

As you begin a physical therapy regimen and/or exercise program, your doctor may prescribe therapies like ultrasound, electric stimulation, hot packs, cold packs, and manual “hands on” therapy to reduce your pain and muscle spasms. At first, the exercises you learn may be gentle stretches or posture changes to reduce the back pain or leg symptoms. When you have less pain, more vigorous aerobic exercises (such as stationary bicycling or swimming) combined with strengthening/stretching exercises will likely be used to improve flexibility, strength, endurance, and the ability to return to a more normal lifestyle. Developing your back and stomach muscles will help stabilize your spine and support your body. Exercise instruction should start right away and be modified as recovery progresses. Learning and continuing an exercise and stretching program are also important parts of treatment, as is maintaining a reasonable body weight.

The presence of this “cracked vertebra” (spondylolysis) or “slippage” (spondylolisthesis) by itself usually does not represent a dangerous condition in the adult. Therefore, treatment is aimed at pain relief and increasing the patient’s ability to function. Although none of the nonsurgical treatments will correct the “crack” or “slippage” they can provide long-lasting pain control without requiring more invasive treatment. A comprehensive program may require three or more months of supervised treatment.

Spondylolisthesis surgery

No definitive standards exist for surgical treatment. Surgery is reserved for that small percentage of patients whose pain cannot be relieved by nonsurgical treatment methods. The pain may be caused by a pinched nerve, movement of the unstable cracked vertebra, or from nearby discs which are being affected. If a spinal nerve is being compressed by the forward slip, surgery may be needed to reopen a “tunnel,” or space, for the nerve. In addition to relieving pressure on a nerve around the crack or slippage, a stabilizing procedure or fusion may be recommended. This will stop any further slippage of the vertebra and also will prevent recurrent nerve pressure from developing at this site. Occasionally the “crack” in the vertebra can be repaired by placing bone graft from the pelvis to the site of the crack. A fusion can be performed from the front (anterior approach) or the back (posterior approach). Both require the placement of bone graft or bone graft substitute and/or instrumentation between the vertebrae being fused. The choice of approach to the fusion (front or back) is influenced by many technical factors including need for spur removal, location of the spurs, anatomic variation between patients and the experience of your surgeon. The success rate of fusion surgery for relief of isthmic spondylolisthesis is over 75%. After surgery, you will remain in the hospital for at least a few days, and most patients are able to return to work within six to nine months. A thorough postoperative rehabilitation program is advisable to help you resume the normal activities of daily living.

Surgery may be recommended for spondylolisthesis patients who have:

- Severe or high-grade slippage

- Slippage that is progressively worsening

- Back pain that has not improved after a period of nonsurgical treatment

Surgical treatment includes a varying combination of decompression, fusion with or without instrumentation or interbody fusion. Patients with instability are more likely to require operative intervention. Some surgeons recommend a reduction of the spondylolisthesis if able as this not only decreases foraminal narrowing but also can improve spinopelvic sagittal alignment and decrease the risk for further degenerative spinal changes in the future. The reduction can be more difficult and riskier in higher grade and impacted spondylolisthesis.

Surgical procedures

Surgery for both degenerative spondylolisthesis and spondylolytic spondylolisthesis includes removing the pressure from the nerves and spinal fusion.

Removing the pressure involves opening up the spinal canal. This procedure is called a laminectomy.

Spinal fusion is essentially a “welding” process. The basic idea is to fuse together the painful vertebrae so that they heal into a single, solid bone. Spinal fusion between the fifth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum is the surgical procedure most often used to treat patients with spondylolisthesis.

The goals of spinal fusion are to:

- Prevent further progression of the slip

- Stabilize the spine

- Alleviate significant back pain

Spinal fusion eliminates motion between the damaged vertebrae and takes away some spinal flexibility. The theory is that, if the painful spine segment does not move, it should not hurt.

During the procedure, the doctor will first realign the vertebrae in the lumbar spine. Small pieces of bone—called bone graft—are then placed into the spaces between the vertebrae to be fused. Over time, the bones grow together—similar to how a broken bone heals.

Prior to placing the bone graft, your doctor may use metal screws and rods to further stabilize the spine and improve the chances of successful fusion.

In some cases, patients with high-grade slippage will also have compression of the spinal nerve roots. If this is the case, your doctor may first perform a procedure to open up the spinal canal and relieve pressure on the nerves before performing the spinal fusion.

Surgical candidates with degenerative spondylolisthesis

Surgery for degenerative spondylolisthesis is generally reserved for the patient who does not improve after a trial of nonsurgical treatment for at least 3 to 6 months. In making a decision about surgery, your doctor will also take into account the extent of arthritis in your spine, as well as whether your spine has excessive movement.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis patients who are candidates for surgery often are unable to walk or stand, and have a poor quality of life due to the pain and weakness.

Surgical candidates with spondylolytic spondylolisthesis

Patients with symptoms that have not responded to nonsurgical treatment for at least 6 to12 months may be candidates for surgery.

If the slippage is getting worse or the patient has progressive neurologic symptoms, such as weakness, numbness, or falling, and/or symptoms of cauda equina syndrome, surgery may help.

Surgical recovery

The fusion process takes time. It may be several months before the bone is solid, although your comfort level will often improve much faster.

Surgical outcomes

The majority of patients with spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are free from pain and other symptoms after treatment. In most cases, sports and other activities can be resumed gradually with few complications or recurrences.

To help prevent future injury, your doctor may recommend that your child do specific exercises to stretch and strengthen the back and abdominal muscles. In addition, regular check-ups are needed to ensure that problems do not develop.

References- Tenny S, Gillis CC. Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430767

- Wiltse LL. Classification, Terminology and Measurements in Spondylolisthesis. Iowa Orthop J. 1981;1:52–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2328707/pdf/iowaorthj00033-0056.pdf

- Tenny S, Gillis CC. Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430767

- Burton MR, Mesfin FB. Isthmic Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441846

- McCunniff PT, Yoo H, Dugarte A, Bajwa NS, Toy JO, Ahn UM, Ahn NU. Bilateral Pars Defects at the L4 Vertebra Result in Increased Degeneration When Compared With Those at L5: An Anatomic Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016 Feb;474(2):571-7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4563-8

- Burton MR, Dowling TJ, Mesfin FB. Isthmic Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441846

- Hegde D, Mehra S, Babu S, Ballal A. A Study to Assess the Functional Outcome of Decompression and Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion of Low Grade Spondylolisthesis of Lumbar Vertebra. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Mar;11(3):RC01-RC03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25135.9531

- Joelson A, Diarbakerli E, Gerdhem P, Hedlund R, Wretenberg P, Frennered K. Self-Image and Health-Related Quality of Life Three Decades After Fusion In Situ for High-Grade Isthmic Spondylolisthesis. Spine Deform. 2019 Mar;7(2):293-297. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2018.08.012

- Endler P, Ekman P, Ljungqvist H, Brismar TB, Gerdhem P, Möller H. Long-term outcome after spinal fusion for isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults. Spine J. 2019 Mar;19(3):501-508. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.08.008

- Konan LM, Davis DD, Mesfin FB. Traumatic Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. [Updated 2021 Aug 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448159

- Moon AS, Atesok K, Niemeier TE, Manoharan SR, Pittman JL, Theiss SM. Traumatic Lumbosacral Dislocation: Current Concepts in Diagnosis and Management. Adv Orthop. 2018 Oct 28;2018:6578097. doi: 10.1155/2018/6578097

- Guerado E, Cervan AM, Cano JR, Giannoudis PV. Spinopelvic injuries. Facts and controversies. Injury. 2018 Mar;49(3):449-456. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.03.001

- Rahman RK, Perra J, Weidenbaum M. Wiltse and Marchetti/Bartolozzi classification of spondylolisthesis – guidelines for treatment. In: Bridwell KH, Dewald RL, editors. The Textbook of Spinal Surgery. 3rd. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Wilkins; 2011. pp. 596–562.

- Konieczny MR, Senyurt H, Krauspe R. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Child Orthop. 2013 Feb;7(1):3-9. doi: 10.1007/s11832-012-0457-4

- Seitsalo S, Osterman K, Poussa M. Scoliosis associated with lumbar spondylolisthesis. A clinical survey of 190 young patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988 Aug;13(8):899-904. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198808000-00005

- McPhee IB, O’Brien JP. Scoliosis in symptomatic spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980 May;62-B(2):155-7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.62B2.7364825

- Hoel RJ, Brenner RM, Polly DW Jr. The Challenge of Creating Lordosis in High-Grade Dysplastic Spondylolisthesis. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2018 Jul;29(3):375-387. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2018.03.006

- Meyerding HW. Spondyloptosis. Surg Gynaecol Obstet. 1932;54:371–377.

- He LC, Wang YX, Gong JS, Griffith JF, Zeng XJ, Kwok AW, Leung JC, Kwok T, Ahuja AT, Leung PC. Prevalence and risk factors of lumbar spondylolisthesis in elderly Chinese men and women. (2014) European radiology. 24 (2): 441-8. doi:10.1007/s00330-013-3041-5