What is stratum corneum

Stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis and marks the final stage of keratinocyte maturation and development. The stratum corneum is the final line of defense (barrier) for the skin against environmental assaults. Additionally, the stratum corneum aids in hydration and water retention, which prevents cracking. Stratum corneum is made up of corneocytes, which are anucleated keratinocytes that have reached the final stage of keratinocyte differentiation 1. Corneocytes retain keratin filaments within a filaggrin matrix, and the cornified lipid envelope replaces the keratinocyte plasma membrane. These flat cells are organized in a brick and mortar formation within a lipid-rich extracellular matrix. Pathophysiology of the stratum corneum is typically secondary to either protein or lipid defects. Other concerning signs include parakeratosis, which describes a corneocyte that has retained its nucleus. Clinically, skin scaling usually characterizes diseases of the stratum corneum.

Normally, the stratum corneum is relatively dry, which makes the surface unsuitable for the growth of many microorganisms. Maintenance of this barrier involves coating the surface with the secretions of sebaceous and sweat glands (discussed in a later section). The process of keratinization occurs everywhere on exposed skin surfaces except over the anterior surface of the eyes. Although the stratum corneum is water resistant, it is not waterproof. Water from the interstitial fluids slowly penetrates the surface and evaporates into the surrounding air. This process, called insensible perspiration, accounts for a loss of roughly 500 ml (about 1 pint) of water per day.

Keratinocytes at the basal layer of the epidermis are proliferative and as the cells mature up the epidermis, slowly lose proliferative potential and undergo programmed destruction. These finally differentiated, enucleated keratinocytes are termed corneocytes, and retain only keratin filaments embedded in filaggrin matrix. Cornified lipid envelopes replace the plasma membranes of the previous keratinocytes, and the cells flatten, connecting to one another with corneodesmosomes and stacking as layers to form the stratum corneum. This outermost barrier level is made up of a network of corneocytes and extracellular lipid matrix. The stratum corneum functions as a two compartment system, with the hydrophobic, protein-rich corneocytes sequestered in a lipid-enriched matrix. This network is organized in a “bricks and mortar” formation, with the extracellular matrix organizing into lamellar membranes.

It takes 15–30 days for a cell to move superficially from the stratum basale to the stratum corneum. The dead cells in the exposed stratum corneum layer usually remain for two weeks before they are shed or washed away. Thus, the deeper portions of the epithelium—and all underlying tissues—are always protected by a barrier composed of dead, durable, and expendable cells.

Scaling is the most common clinical manifestation of stratum corneum disease and represents inadequate or flawed keratinization and desquamation. Those diseases characterized by scaling, and thus stratum corneum breakdown, include dermatitis (eczema), psoriasis, and the ichthyoses. Both eczema and psoriasis result from underlying epidermal changes that cause pathology at the level of the stratum corneum. On the other hand, the ichthyoses result from underlying defects in keratinization.

Dermatitis, or eczema, is a skin reaction secondary to an underlying process such as an immune response or infection. Dermatitis is characterized by a disruption in corneocyte formation in the setting of underlying epidermal keratinocyte spongiosis. Consequently, there is keratinocyte hyperproliferation and disturbed keratinization, which both cause scaling. In psoriasis, activated lymphocytes release cytokines which trigger epidermal hyperproliferation and leukocyte infiltration that similarly causes keratinocyte hyperproliferation and disturbed keratinization, resulting in scaling. The inherited ichthyoses result from genetic defects that phenotypically present as skin scaling and diffuse xerosis.

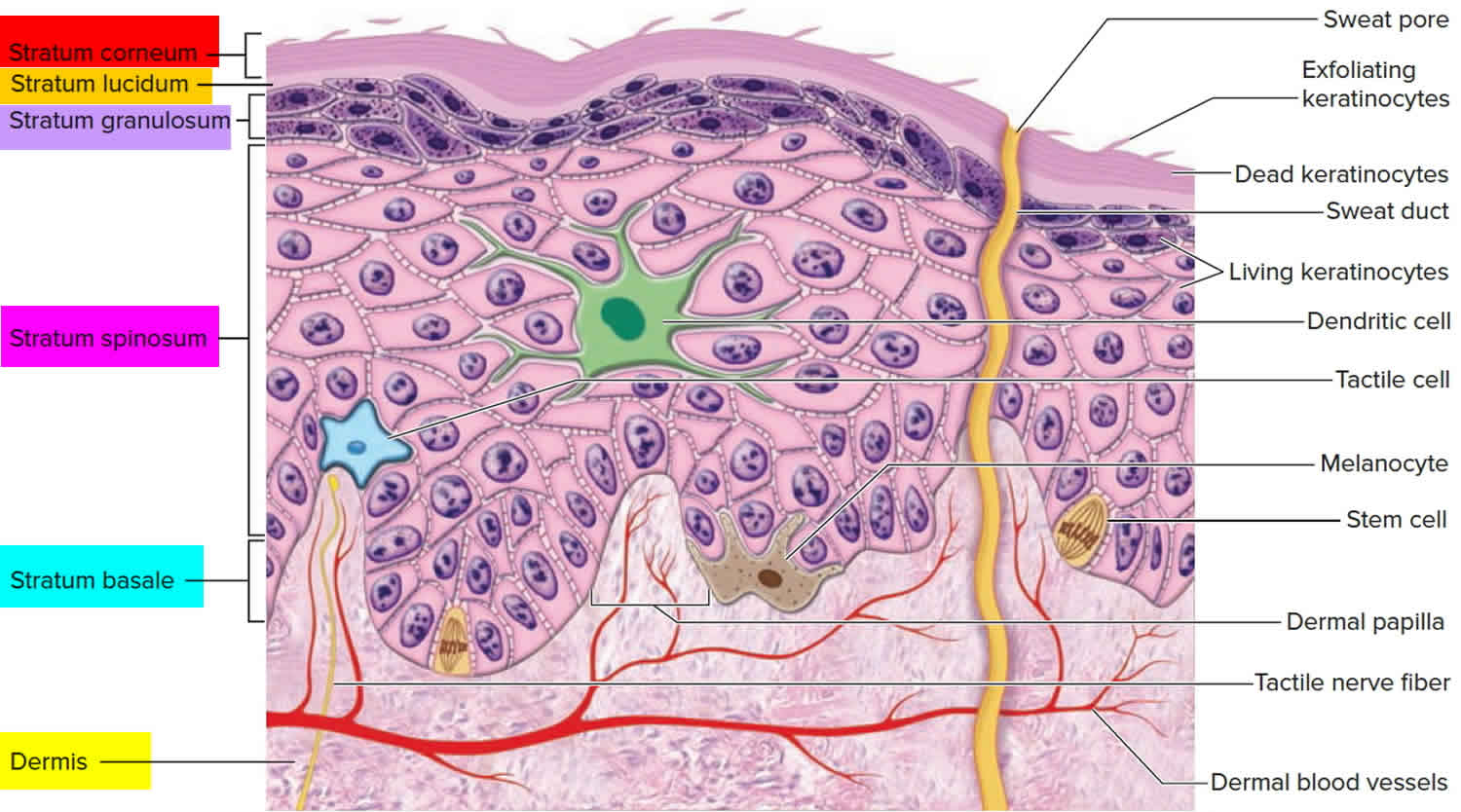

Figure 1. Skin layers

Figure 2. Stratum corneum (the stratum corneum is the surface horny layer consisting of stacks of dead cells without nuclei)

Stratum corneum thickness

The human stratum corneum comprises 15 or so layers of flattened corneocytes and is divided into two layers: the stratum compactum, and the stratum disjunctum. The stratum compactum is the deep, dense, cohesive layer, while the stratum disjunctum is looser and lies superficially to the stratum compactum. As the stratum disjunctum continues to lose adhesiveness secondary to decreased inter-corneocyte adhesion, the cells desquamate.

Stratum corneum function

The stratum corneum serves as the final skin barrier to the outside world. For the keratinocytes produced in the stratum basale, the goal is differentiation to the anucleated corneocytes that make up the stratum corneum. This most superficial layer of the epithelium prevents desiccation and serves as a shield against the environment. The 2 components of the stratum corneum, the extracellular lipid matrix, and the corneocytes, serve different functions. The corneocytes, which are the terminally differentiated keratinocytes, provide mechanical reinforcement, protect underlying mitotically active cells from ultraviolet (UV) damage, regulate cytokine-mediated initiation of inflammation, and maintain hydration. The extracellular lipid matrix that creates the brick and mortar organization of the stratum corneum regulates permeability, initiates corneocyte desquamation, has antimicrobial peptide activity and excludes toxins, and allows for selective chemical absorption.

Defects in the stratum corneum may occur secondary to lipid or protein dysfunction. Lipid abnormalities may stem from a variety of causes and generally result in defective barrier function resulting in increased transepidermal water loss and desquamation. An acute loss of lipids from the stratum corneum may occur secondary to the topical application of organic solvents or detergents, which extract lipids and allow the passive loss of extracellular calcium and potassium. Deficiency in essential fatty acids also results in lipid abnormalities and manifests as increased transepidermal water loss, scaling, and alopecia. Lipid abnormalities can also occur secondary to genetic disorders, such as deficiency in steroid sulfatase leading to recessive X-linked ichthyosis.

In addition to pathologies secondary to lipid abnormalities, stratum corneum protein abnormalities can also result in defects in the stratum corneum layer of the epidermis. Defects in corneodesmosomes, the junctional proteins that connect corneocytes, result in diseases such as peeling skin disease. Defects in the profilaggrin and filaggrin proteins cause significant damage to the stratum corneum, and profilaggrin defects are associated with both ichthyosis vulgaris and harlequin ichthyosis. Defects in the cornified envelopes of the stratum corneum cells can also result in pathologies such as keratosis follicularis and psoriasis.

Finally, parakeratosis refers to corneocytes in the stratum corneum with retained nuclei. While retention of nuclei in stratum corneum cells is normal in mucosal surfaces, parakeratosis in other skin is abnormal. Parakeratosis typically signifies increased cell turnover, which can be secondary to inflammatory or neoplastic processes. Additionally, when corneocytes retain their nuclei, there is associated thinning and eventual loss of the granular layer.

References