Stress ulcer

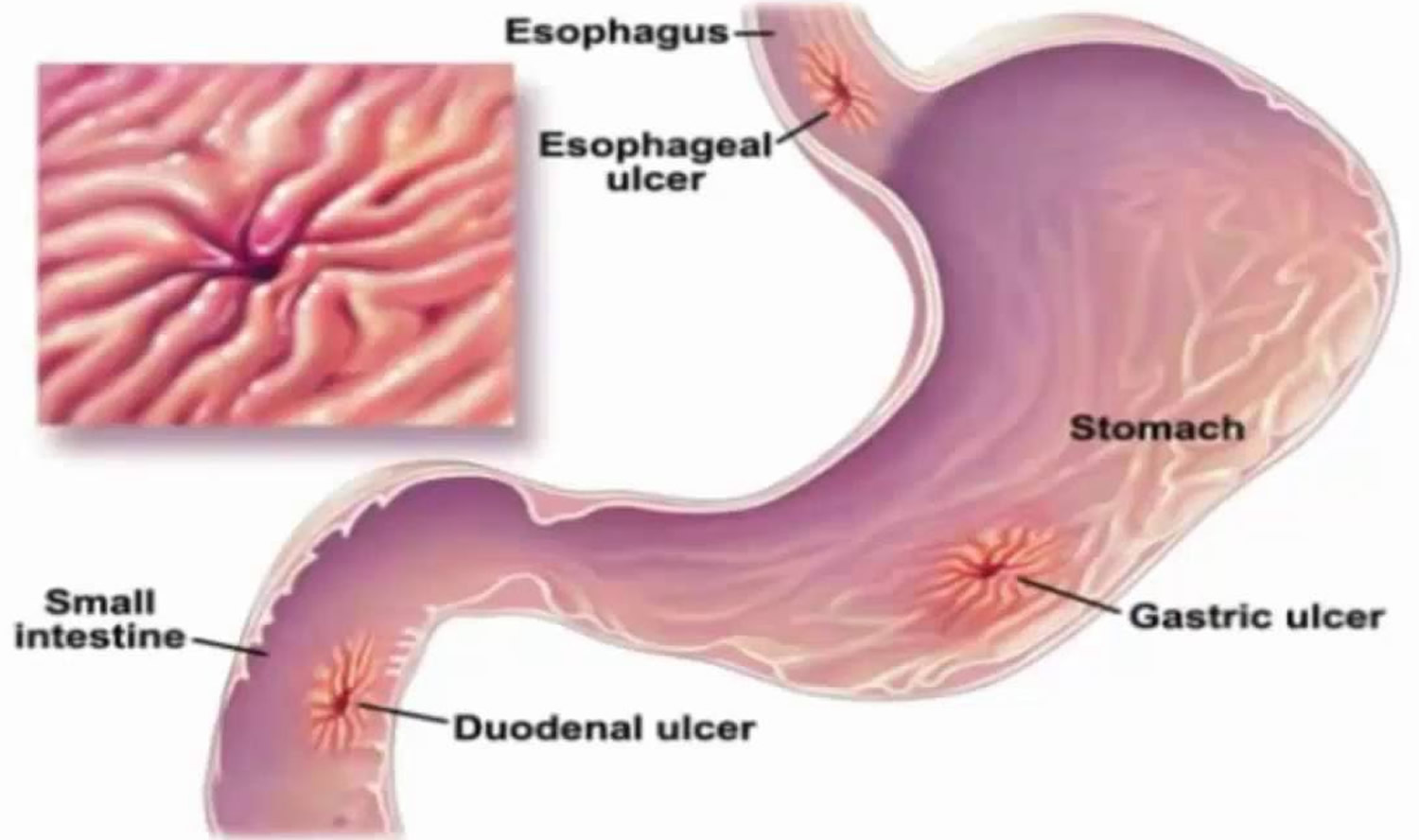

Stress ulcers are stress-induced gastritis, stress-related erosive syndrome, stress ulcer syndrome, and stress-related mucosal disease, where the gastric and sometimes esophageal or duodenal mucosal barrier is disrupted secondary to a severe acute illness 1. Stress ulcer may present in the form of erosive gastritis ranging from asymptomatic superficial lesions, and occult gastrointestinal bleed to overt clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding. The stress ulcers secondary to systemic burns are known as Curling ulcer, stress ulcers in patients with acute traumatic brain injury are known as Cushing ulcer 1. The gastric body and fundus are common locations for stress ulcerations but can also be seen in antrum and duodenum 2.

The incidence of stress ulcer is not well known but is thought to almost always occur in severe acute illness. The most common presentation of stress ulceration is in the form of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and gastrointestinal bleed secondary to stress ulcerations may range from 1.5% to 15% depending on whether or not patients received stress ulcer prophylaxis. The incidence of stress ulceration and its complications are known to be declining with the advent of active prophylaxis methods for the prevention of stress-related gastritis. Patients with gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to stress ulceration have increased morbidity and mortality compared to those who do not have gastrointestinal bleed. Hence stress ulcer prophylaxis has been the center of many randomized clinical trials. Very rarely (less than 1% of the times), stress ulcers can cause perforation and perforation related complications 2.

Stress ulcer causes

The major risk factors for the development of stress ulcers include:

- Mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours

- Abnormal coagulation profile such as platelet count less than 50,000, INR greater than 1.5 and PTT greater than 2 times the control value

- Sepsis or septic shock

- Use of vasopressors

- Use of high dose systemic corticosteroids (more than 250 mg or the equivalent of hydrocortisone per day)

- Hepatic failure

- Renal failure

- Multiorgan failure

- Burns of more than 30% of body surface area

- Head trauma

- Lack of sanitation during intensive care unit (ICU) stay

- History of gastrointestinal bleeds within a year 3

Stress ulcer results from damage to the mucosal barrier secondary to systemic stress resulting in multiple superficial erosions of the gastric mucosa 1. The possible pathological changes leading to ulceration can be an impaired mucosal barrier where the mucosal glycoprotein is denuded by increased concentrations of refluxed bile salts or uremic toxins due to a critical illness. Increased secretion of gastric acid in response to higher secretion of gastrin hormone in patients is also thought to be responsible for stress ulceration. However, this is more commonly seen in patients with acute neurological trauma than other stress-related diseases. Helicobacter pylori infection has also been associated with stress ulcers though the evidence is limited. There could be a subgroup of critical care patients who may present with overt gastrointestinal bleeding without stress ulceration or stress-related mucosal damage, such as a patient with variceal bleeds, vascular anomalies, or diverticulosis. Hence these gastrointestinal bleeds may not respond adequately to stress ulcer prophylaxis or anti-reflux therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) or antihistamines 4.

Patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) who receive positive pressure ventilation (PPV) for more than 3 days are especially susceptible to mucosal damage due to splanchnic hypo-perfusion, which is more pronounced at positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) levels of 15-20 cm of H2O 5.

Stress ulcer pathophysiology

Gastric acid production is necessary for the body to digest food and break down nutritional components into absorbable amino acids, carbohydrates, and fats. Most of the acid is produced when gastric pH stimulates the release of gastrointestinal using the release and activation of various digestive enzymes. The stomach is a relatively acidic environment with a pH of less than 4.0, and this can drop to 2.0 with the presence of parietal cells. Parietal cells live in the fundus and the body of the stomach and secrete hydrogen ions. Hydrogen ion secretion is stimulated by three predominant substances 1 .

- Neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) stimulates parietal cells via the phospholipase pathway to secrete hydrogen. Phospholipase is stimulated on the cellular wall, which then cleaves PIP into IP3 and DAG, releasing calcium ions into the cytoplasm. These calcium ions bind calmodulin and stimulate protein kinase C (PKC). PKC leads to the phosphorylation and activation of the hydrogen/potassium ATPase (H/K ATPase), resulting in acid secretion. The source of acetylcholine (ACh) is from the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X).

- Gastrin is a hormone known to stimulate hydrogen ion secretion via the same mechanism of acetylcholine (ACh) resulting in the activation of the H/K ATPase. Gastrin is predominantly secreted via the G cells, located in the antrum of the stomach, which are stimulated by the presence of amino acids and acetylcholine (ACh) in the gastric lumen.

- Histamine stimulates parietal cells to secrete hydrogen ions via the cAMP pathway via the activation of protein kinase A and activate the H/K ATPase. Histamine is predominantly secreted via the mast cells from the surrounding gastric tissues.

The dysregulation of the above-mentioned mechanisms can result in hemorrhagic or erosive gastropathy, also known as stress ulcer or stress gastritis. The mucosal barrier is disrupted secondary to an acute illness.

Stress ulcer prophylaxis

Stress ulcer prophylaxis has been a center of debate for various national and international societies of critical care. Stress ulcer prophylaxis has shown to be of benefit in preventing gastrointestinal bleeding related to stress ulceration, but the guidelines regarding the indications, drug selection, and duration of stress ulcer prophylaxis are not clear 6.

Surviving sepsis campaign recommends stress ulcer prophylaxis for patients on mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and patients with coagulopathy. The other indications for stress ulcer prophylaxis include sepsis and septic shock, severe burn injuries, use of high dose steroids, and neurological trauma. Surviving sepsis campaign recommends the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) over antihistamines for stress ulcer prophylaxis. Even though multiple studies have challenged the superiority of one over the other, proton pump inhibitors are the most common agents used in the ICU and burn unit as stress ulcer prophylaxis. Sucralfate an ulcer-healing drug can also be used for stress ulcer prophylaxis, it is shown to be less effective than proton pump inhibitor and histamine blockers but safer regarding adverse reactions. Cytoprotective agents like prostaglandin analogs (misoprostol) can also be used for stress ulcer prophylaxis. They not only suppress acid secretion via a cyclic AMP pathway but also enhance the mucosal barrier of the gastric epithelium. However, they are still under investigation and lack adequate evidence for use in stress ulcer prophylaxis. The adverse effects of the frequent use of proton pump inhibitors in this population, including but not limited to, Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, pneumonia, and adverse drug interactions 7.

The duration of stress ulcer prophylaxis is usually for the period of critical illness or the duration of mechanical ventilation, and sometimes it can be continued until the patient begins to tolerate the oral diet 8.

Stress ulcer symptoms

The most common mode of presentation of stress ulcers is the onset of acute upper gastrointestinal bleed like vomiting of blood (hematemesis) or black tarry stools (melena) in a patient with acute critical illness. The patient may or may not have hemodynamic instability in the presence of bleeding, and most of these patients do have a drop in hemoglobin concentration requiring blood transfusions.

Patients who may have an increased risk of stress gastritis are those with severe illness, major surgery, massive burn injury, head injury associated with raised intracranial pressure, sepsis and positive blood culture results, severe polytrauma, and multiple system organ failure 9. The clinician should have a high index of suspicion in patients in these settings who are noted to have decreased hematocrit values and who are not receiving prophylaxis for stress gastritis.

Some types of psychiatric stressors (eg, major, untreated depression) can cause stress gastritis 9.

Before the diagnostic evaluation for stress ulceration, stabilization of the patients should take priority. Monitor the need for fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion and reversal of coagulopathy if needed.

Stress ulcer diagnosis

A high degree of clinical awareness is the key to early diagnosis of stress-induced gastritis. The presence of any of the previously discussed clinical features should alert the clinician to the presence of stress gastritis.

In order to detect a stress ulcer, your doctor may first take a medical history and perform a physical exam. You then may need to undergo diagnostic tests, such as:

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy should be performed. Your doctor may use a scope to examine your upper digestive system (endoscopy). During endoscopy, your doctor passes a hollow tube equipped with a lens (endoscope) down your throat and into your esophagus, stomach and small intestine. Using the endoscope, your doctor looks for ulcers. Stress ulcers are seen as small superficial mucosal erosions or ulcerations in the gastric body and fundus. If your doctor detects an ulcer, small tissue samples (biopsy) may be removed for examination in a lab. A biopsy can also identify whether Helicobacter pylori is in your stomach lining. Testing for Helicobacter pylori infection like urease breath test or stool antigen test can also be undertaken for refractory stress ulceration.

- Laboratory tests for Helicobacter pylori. Your doctor may recommend tests to determine whether the bacterium Helicobacter pylori is present in your body. He or she may look for H. pylori using a blood, stool or breath test. The breath test is the most accurate. Blood tests are generally inaccurate and should not be routinely used. For the breath test, you drink or eat something that contains radioactive carbon. Helicobacter pylori breaks down the substance in your stomach. Later, you blow into a bag, which is then sealed. If you’re infected with H. pylori, your breath sample will contain the radioactive carbon in the form of carbon dioxide. If you are taking an antacid prior to the testing for H pylori, make sure to let your doctor know. Depending on which test is used, you may need to discontinue the medication for a period of time because antacids can lead to false-negative results.

- Other useful investigations and diagnostic tools include the following:

- Hematocrit level

- Coagulation profile

If the endoscopy shows an ulcer in your stomach, a follow-up endoscopy should be performed after treatment to show that it has healed, even if your symptoms improve.

- Gastric lavage is a useful test to confirm whether blood is present in the upper gastrointestinal tract 9 and to quantify the amount of blood if found. This is roughly assessed by how much normal saline it takes before the aspirate becomes clear.

Stress ulcer treatment

Management of stress-induced gastritis includes prompt identification and prevention of complications related to stress ulceration. The management can be divided into pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

The nonpharmacological interventions include early enteral feeding, nasogastric tube placement intravenous fluid resuscitation, blood transfusion, and reversal of coagulopathy by platelets transfusion or transfusion of fresh frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate 10.

The medical management of patients with stress ulcers is more or less similar to the management of peptic ulcer disease in general. The medication targeting acid peptic disease includes proton pump inhibitors, antihistaminic, and ulcer-healing drugs like sucralfate. Patients with overt gastrointestinal bleeding from ulceration will require endoscopic evaluation and management of the stress ulcers. Endoscopic therapies may include epinephrine injection, electro-cauterization, or clipping of the bleeding vessels. Bleeding ulcers refractory to localized endoscopic treatment may need embolization of the culprit vessel or rarely surgical intervention as a last resort. Surgical interventions are commonly indicated for patients with refractory bleeding despite endoscopic or angiographic treatment or patients with unstable hemodynamics to undergo endoscopic or angiographic procedures. Surgeries are performed as an ultimate life-saving approach 11.

Sometimes the ulcers can be deep enough to cause perforation of the gastric wall leading to acute peritonitis requiring urgent laparotomy. In comparison to other forms of stress ulcerations, perforations are most likely to happen with Cushing and Curling ulcers as they tend to be deep and can cause extensive necrosis. Mortality without surgical intervention in these patients who develop free wall gastrointestinal perforation is almost 100% 12.

Stress ulcer prognosis

Patients with stress ulceration usually have poor prognosis secondary to the underlying critical illness. Moreover, gastrointestinal bleeds in these patients secondary to stress-related mucosal disease is independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality. More often, these patients are too unstable for advanced endoscopic or surgical procedures to suppress gastrointestinal bleed, leading to worse outcomes. Hence, aggressive prophylactic measures for the appropriate patient population at risk of developing stress ulceration remains the cornerstone in the management of stress-induced gastropathy 13.

References- Siddiqui AH, Siddiqui F. Curling Ulcer (Stress-induced Gastric) [Updated 2019 Nov 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482347

- Siddiqui F, Ahmed M, Abbasi S, Avula A, Siddiqui AH, Philipose J, Khan HM, Khan TMA, Deeb L, Chalhoub M. Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A National Database Analysis. J Clin Med Res. 2019 Jan;11(1):42-48.

- Kumar S, Ramos C, Garcia-Carrasquillo RJ, Green PH, Lebwohl B. Incidence and risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding among patients admitted to medical intensive care units. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2017 Jul;8(3):167-173.

- Cheung LY. Thomas G Orr Memorial Lecture. Pathogenesis, prophylaxis, and treatment of stress gastritis. Am. J. Surg. 1988 Dec;156(6):437-40.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, Osborn TM, Nunnally ME, Townsend SR, Reinhart K, Kleinpell RM, Angus DC, Deutschman CS, Machado FR, Rubenfeld GD, Webb S, Beale RJ, Vincent JL, Moreno R., Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including The Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013 Feb;39(2):165-228.

- Barletta JF, Mangram AJ, Sucher JF, Zach V. Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis in Neurocritical Care. Neurocrit Care. 2018 Dec;29(3):344-357. doi: 10.1007/s12028-017-0447-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-017-0447-y

- Krag M, Perner A, Wetterslev J, Wise MP, Borthwick M, Bendel S, Pelosi P, Keus F, Guttormsen AB, Schefold JC, Møller MH., SUP-ICU investigators. Stress ulcer prophylaxis with a proton pump inhibitor versus placebo in critically ill patients (SUP-ICU trial): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016 Apr 19;17(1):205.

- Barletta JF, Bruno JJ, Buckley MS, Cook DJ. Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis. Crit. Care Med. 2016 Jul;44(7):1395-405.

- Megha R, Lopez PP. Stress-Induced Gastritis. [Updated 2019 Apr 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499926

- Amaral MC, Favas C, Alves JD, Riso N, Riscado MV. Stress-related mucosal disease: incidence of bleeding and the role of omeprazole in its prophylaxis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2010 Oct;21(5):386-8.

- Enquist IF, Karlson KE, Dennis C, Fierst SM, Shaftan GW. Statistically valid ten-year comparative evaluation of three methods of management of massive gastroduodenal hemorrhage. Ann. Surg. 1965 Oct;162(4):550-60.

- Kanchan T, Geriani D, Savithry KS. Curling’s ulcer – have these stress ulcers gone extinct? Burns. 2015 Feb;41(1):198-9.

- Cho J, Choi SM, Yu SJ, Park YS, Lee CH, Lee SM, Yim JJ, Yoo CG, Kim YW, Han SK, Lee J. Bleeding complications in critically ill patients with liver cirrhosis. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2016 Mar;31(2):288-95.