Sudden infant death syndrome

Sudden infant death syndrome or SIDS, is the unexpected and unexplained death, usually during sleep, of a seemingly healthy baby less than a year old that doesn’t have a known cause even after a complete investigation. This investigation includes performing a complete autopsy, examining the death scene, and reviewing the clinical history. When a baby dies, health care providers, law enforcement personnel, and communities try to find out why. They ask questions, examine the baby, gather information, and run tests. If they can’t find a cause for the death, and if the baby was younger than 1 year old, the medical examiner or coroner may call the death SIDS.

Most unexpected deaths occur while the child is asleep in their cot at night. SIDS is sometimes known as “crib death” because the infants often die in their cribs. SIDS is the leading cause of death in children between one month and one year old. Most SIDS deaths occur when babies are between one month and four months old and the majority (90%) of SIDS deaths happen before a baby reaches 6 months of age. However, SIDS deaths can happen anytime during a baby’s first year 1. Infants born prematurely or with a low birth weight are at greater risk, and SIDS is also more common in baby boys, African Americans, and American Indian/Alaska Native infants 1. In the past, the number of SIDS deaths seemed to increase during the colder months of the year. But today, the numbers are more evenly spread throughout the year 2. About 1,360 babies died of SIDS in 2017, the last year for which such statistics are available 3.

Although the cause is unknown, it appears that SIDS might be associated with defects in the portion of an infant’s brain that controls breathing and arousal from sleep.

Researchers have discovered some factors that might put babies at extra risk. They’ve also identified measures you can take to help protect your child from SIDS. Perhaps the most important is placing your baby on his or her back to sleep.

Although the cause of SIDS is unknown, there are steps you can take to reduce the risk. These include:

- Placing your baby on his or her back to sleep, even for short naps. “Tummy time” is for when babies are awake and someone is watching

- Having your baby sleep in your room for at least the first six months. Your baby should sleep close to you, but on a separate surface designed for infants, such as a crib or bassinet.

- Using a firm sleep surface, such as a crib mattress covered with a fitted sheet

- Keeping soft objects and loose bedding away from your baby’s sleep area

- Breastfeeding your baby

- Making sure that your baby doesn’t get too hot. Keep the room at a comfortable temperature for an adult.

- Not smoking during pregnancy or allowing anyone to smoke near your baby.

SIDS is NOT

SIDS is not the cause of every sudden infant death. Each year in the United States, thousands of babies die suddenly and unexpectedly. These deaths are called Sudden Unexpected Infant Death (SUID) or Sudden Unexpected Death in Infancy (SUDI), which is a term used to describe the sudden and unexpected death of a baby. Sudden Unexpected Infant Death (SUID) may be the result of a serious illness or a problem that baby may have been born with, but most SUID deaths occur as a result of either SIDS or a fatal sleep accident.

SUID includes all unexpected deaths: those without a clear cause, such as SIDS, and those from a known cause, such as suffocation. One-half of all SUID cases are SIDS. Many unexpected infant deaths are accidents, but a disease or something done on purpose can also cause a baby to die suddenly and unexpectedly.

“Sleep-related causes of infant death” are those linked to how or where a baby sleeps or slept. These deaths are due to accidental causes, such as suffocation, entrapment, or strangulation. Entrapment is when the baby gets trapped between two objects, such as a mattress and a wall, and can’t breathe. Strangulation is when something presses on or wraps around the baby’s neck, blocking the baby’s airway. These deaths are not SIDS.

Other things that SIDS is NOT:

- SIDS is not the same as suffocation and is not caused by suffocation.

- SIDS is not caused by vaccines, immunizations, or shots.

- SIDS is not contagious.

- SIDS is not the result of neglect or child abuse.

- SIDS is not caused by cribs.

- SIDS is not caused by vomiting or choking.

- SIDS is not completely preventable, but there are ways to reduce the risk.

What is most common age for SIDS?

The majority (90%) of SIDS deaths occur before a baby reaches 6 months of age, and the number of SIDS deaths peaks between 1 month and 4 months of age. However SIDS deaths can occur anytime during a baby’s first year, so parents should still follow safe sleep recommendations to reduce the risk of SIDS until their baby’s first birthday.

Other sleep-related causes of infant death are those that occur in the sleep environment or during sleep time. They include accidental suffocation by bedding, entrapment (when a baby gets trapped between two objects, such as a mattress and wall, and can’t breathe), or strangulation (when something presses on or wraps around a baby’s neck, blocking the baby’s airway). These deaths are not SIDS, but they are Sudden Unexpected Infant Death (SUID) or Sudden Unexpected Death in Infancy (SUDI).

Sudden infant death syndrome causes

Scientists don’t know exactly what causes SIDS at this time. Even though the exact cause of SIDS is unknown, there are ways to reduce the risk of SIDS and other sleep-related causes of infant death.

Scientists and health care providers are working very hard to find the cause or causes of SIDS. More and more research evidence suggests that infants who die from SIDS are born with brain abnormalities or defects 4. These defects are typically found within a network of nerve cells that send signals to other nerve cells. The cells are located in the part of the brain that probably controls breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, and waking from sleep. At the present time, there is no way to identify babies who have these abnormalities, but researchers are working to develop specific screening tests.

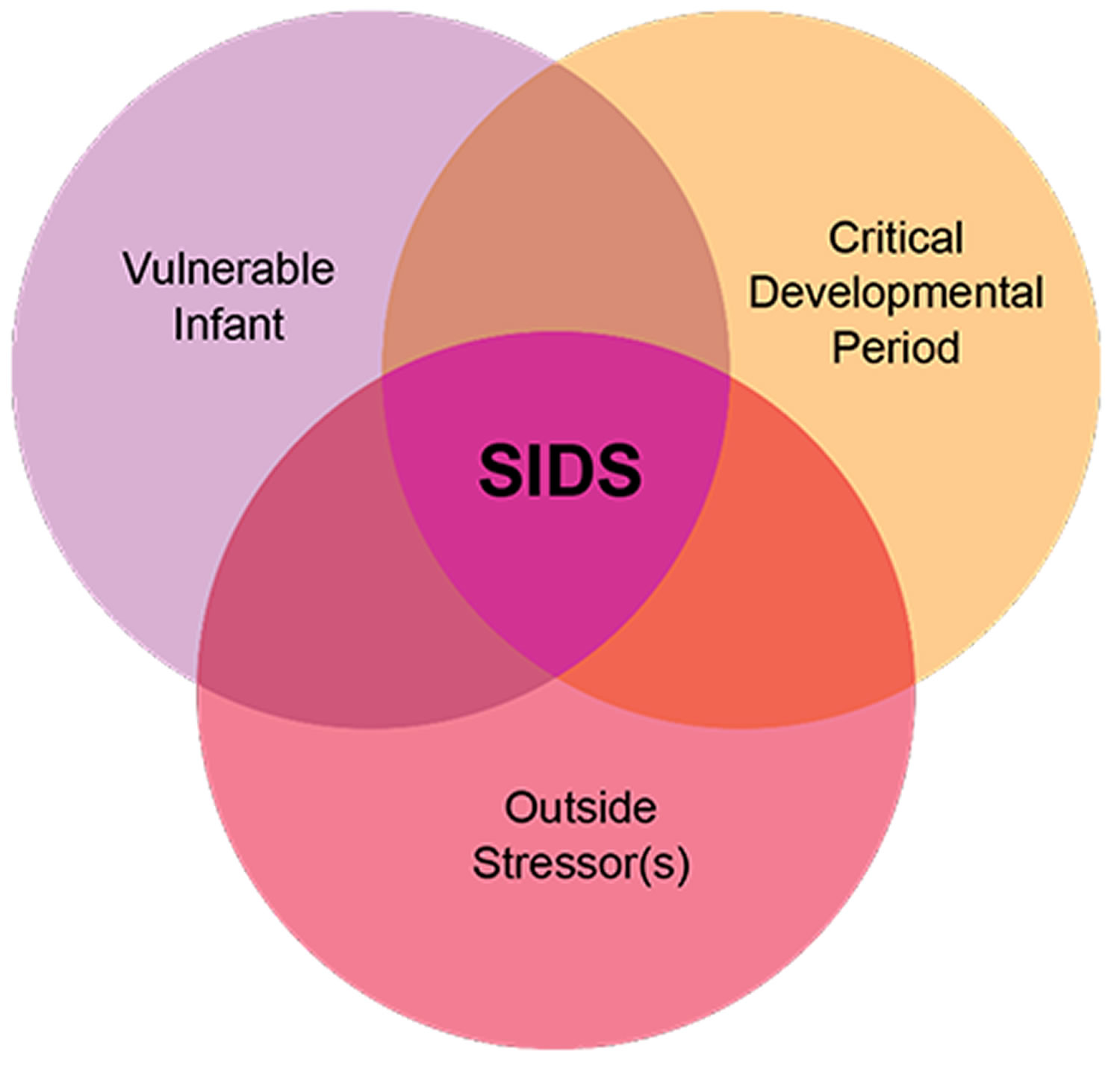

But scientists believe that brain defects alone may not be enough to cause a SIDS death. Evidence suggests that other events (e.g., lack of oxygen, excessive carbon dioxide intake, overheating, an infection) must also occur for an infant to die from SIDS. Researchers use the Triple-Risk Model to explain this concept (see Figure 1). The Triple-Risk Model describes the convergence of three conditions at the same time for an infant to die from SIDS. Having only one of these factors may not be enough to cause death from SIDS, but when all three combine, the chances of SIDS are high 5.

- Vulnerable infant. An underlying defect or brain abnormality makes the baby vulnerable. In the Triple-Risk Model, certain factors—such as defects in the parts of the brain that control respiration or heart rate or genetic mutations—confer vulnerability.

- Critical developmental period. During the infant’s first 6 months of life, rapid growth and changes in homeostatic controls occur. These changes may be evident (e.g., sleeping and waking patterns), or they may be subtle (e.g., variations in breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature). Some of these changes may destabilize the infant’s internal systems temporarily or periodically.

- Outside stressor(s). Most babies encounter and can survive environmental stressors, such as a stomach sleep position, overheating, secondhand tobacco smoke, or an upper respiratory tract infection. However, an already vulnerable infant may not be able to overcome them. Although these stressors are not believed to single-handedly cause infant death, they may tip the balance against a vulnerable infant’s chances of survival.

According to the Triple-Risk Model 5, all three elements must be present for a sudden infant death to occur:

- The baby’s vulnerability is undetected.

- The infant is in a critical developmental period that can temporarily destabilize his or her systems.

- The infant is exposed to one or more outside stressors that he or she cannot overcome because of the first two factors.

For example, many babies experience a lack of oxygen and excessive carbon -dioxide levels when they have respiratory infections or when they re-breathe exhaled air that has become trapped in bedding as they sleep on their stomachs. Normally, infants sense this inadequate air intake, and their brains trigger them to wake up or trigger their heartbeats or breathing patterns to change or compensate. In a baby with an abnormality in the brain stem, however, these protective mechanisms may be less effective, so the child may succumb to SIDS.

Such a scenario might explain why babies who sleep on their stomachs are more susceptible to SIDS.

If caregivers can remove one or more outside stressors, such as placing an infant to sleep on his or her back instead of on the stomach to sleep, they can reduce the risk of SIDS 5.

Figure 1. Triple-Risk Model for SIDS

Genetic polymorphisms

Even though it is unlikely that one defective gene predisposes a baby to SIDS, genes may act in combination with environmental risk factors to result in SIDS 6. Predisposing factors could include polymorphisms in genes involved in metabolism and the immune system, as well as conditions that affect the brain stem and cause neurochemical imbalances in the brain. Polymorphisms may predispose infants to death in critical situations.

One example of a genetic polymorphism that may be associated with SIDS involves the immune system. Studies in Norway and Germany have revealed an association between partial deletions of the highly polymorphic C4 gene and mild respiratory infections in infants who have died of SIDS 7. Differences in C4 expression may contribute to differences in the strength of the immune system by regulating the predisposition to infectious and autoimmune diseases that put infants at higher risk of SIDS. Partial deletions of the C4 gene are fairly common and are found in up to 20 percent of the white population. Other examples of polymorphisms and genetic mutations are more common in SIDS infants, but how they are related to SIDS is unknown.

Also, many SIDS infants have an activated immune system, which may indicate that they are vulnerable to simple infections. In one study, approximately 50 percent of infants who died of SIDS had a mild upper airway infection before death 8.

Genetic mutations

Genetic mutations can give rise to genetic disorders that can cause sudden unexpected death. If there is a family history of a metabolic disorder, genetic screening can determine if one or both of the parents are carriers of the mutation, and, if so, the baby can be tested soon after birth. If the condition is not identified, however, the resulting death may be mistaken for SIDS.

When a sudden infant death does occur, it is important to search for genetic mutations; infants with such mutations should be excluded from those diagnosed as dying of SIDS 7. One example of a genetic mutation that may be misdiagnosed as SIDS is a deficiency in fatty acid metabolism. Some babies who die suddenly may be born with a metabolic disorder that prevents them from properly processing fatty acids. A buildup of fatty acid metabolites can lead to a rapid disruption in breathing and heart function—a disruption that can be fatal.

Some infants who have been diagnosed as dying from SIDS have rare mutations that affect the function of the cardiac conduction system. These mutations can lead to a deadly arrhythmia.

Physical and sleep environmental factors

A combination of physical and sleep environmental factors can make an infant more vulnerable to SIDS. These factors vary from child to child.

Physical factors

Physical factors associated with SIDS include:

- Brain defects. Some infants are born with problems that make them more likely to die of SIDS. In many of these babies, the portion of the brain that controls breathing and arousal from sleep hasn’t matured enough to work properly.

- Low birth weight. Premature birth or being part of a multiple birth increases the likelihood that a baby’s brain hasn’t matured completely, so he or she has less control over such automatic processes as breathing and heart rate.

- Respiratory infection. Many infants who died of SIDS had recently had a cold, which might contribute to breathing problems.

Sleep environmental factors

The items in a baby’s crib and his or her sleeping position can combine with a baby’s physical problems to increase the risk of SIDS. Examples include:

- Sleeping on the stomach or side. Babies placed in these positions to sleep might have more difficulty breathing than those placed on their backs.

- Sleeping on a soft surface. Lying face down on a fluffy comforter, a soft mattress or a waterbed can block an infant’s airway.

- Sharing a bed. While the risk of SIDS is lowered if an infant sleeps in the same room as his or her parents, the risk increases if the baby sleeps in the same bed with parents, siblings or pets.

- Overheating. Being too warm while sleeping can increase a baby’s risk of SIDS.

Risk factors for SIDS

Although sudden infant death syndrome can strike any infant, researchers have identified several factors that might increase a baby’s risk.

Research shows that several factors put babies at higher risk for SIDS and other sleep-related causes of infant death. Babies who usually sleep on their backs but who are then placed to sleep on their stomachs, such as for a nap, are at very high risk for SIDS.

Babies are at higher risk for SIDS if:

- Sex. Boys are slightly more likely to die of SIDS.

- Age. Infants are most vulnerable between the second and fourth months of life.

- Race. For reasons that aren’t well-understood, nonwhite infants are more likely to develop SIDS.

- Family history. Babies who’ve had siblings or cousins die of SIDS are at higher risk of SIDS.

- Secondhand smoke. Babies who live with smokers have a higher risk of SIDS.

- Are exposed to cigarette smoke in the womb or in their environment, such as at home, in the car, in the bedroom, or other areas.

- Being premature. Both being born early and having a low birth weight increase your baby’s chances of SIDS.

- Sleep on their stomachs

- Sleep on soft surfaces, such as an adult mattress, couch, or chair or under soft coverings

- Sleep on or under soft or loose bedding

- Get too hot during sleep

- Sleep in an adult bed with parents, other children, or pets; this situation is especially dangerous if:

- The adult smokes, has recently had alcohol, or is tired.

- The baby is covered by a blanket or quilt.

- The baby sleeps with more than one bed-sharer.

- The baby is younger than 11 to 14 weeks of age.

- Maternal risk factors. During pregnancy, the mother also affects her baby’s risk of SIDS, especially if she:

- Is younger than 20

- Smokes cigarettes

- Uses drugs or alcohol

- Has inadequate prenatal care

Sudden infant death syndrome prevention

There’s no guaranteed way to prevent SIDS, but research shows that there are several ways to reduce the risk of SIDS and other sleep-related causes of infant death.

You can help your baby sleep more safely by following these tips:

- Back to sleep. Place your baby to sleep on his or her back, rather than on the stomach or side, every time you or anyone else put the baby to sleep for the first year of life. This isn’t necessary when your baby’s awake or able to roll over both ways without help. Don’t assume that others will place your baby to sleep in the correct position — insist on it. Advise baby sitters and child care providers not to use the stomach position to calm an upset baby.

- The back sleep position is the safest position for all babies, until they are 1 year old. Babies who are used to sleeping on their backs, but who are then placed to sleep on their stomachs, like for a nap, are at very high risk for SIDS. If baby rolls over on his or her own from back to stomach or stomach to back, there is no need to reposition the baby. Starting sleep on the back is most important for reducing SIDS risk. Preemies (infants born preterm) should be placed on their backs to sleep as soon as possible after birth.

- Keep the crib as bare as possible. Use a firm mattress and avoid placing your baby on thick, fluffy padding, such as lambskin or a thick quilt. Don’t leave pillows, fluffy toys or stuffed animals in the crib. These can interfere with breathing if your baby’s face presses against them.

- Use a firm and flat sleep surface such as a mattress in a safety-approved crib, covered by a fitted sheet with no other bedding or soft items in the sleep area. Never place baby to sleep on soft surfaces, such as on a couch, sofa, waterbed, pillow, quilt, sheepskin, or blanket. These surfaces can be very dangerous for babies. Do not use a car seat, stroller, swing, infant carrier, infant sling or similar products as baby’s regular sleep area. Following these recommendations reduces the risk of SIDS and death or injury from suffocation, entrapment, and strangulation.

- Don’t overheat your baby. To keep your baby warm, try a sleep sack or other sleep clothing that doesn’t require additional covers. Don’t cover your baby’s head.

- Have your baby sleep in in your room. Ideally, your baby should sleep in your room with you, but alone in a crib, bassinet or other structure designed for infants, for at least six months, and, if possible, up to a year.

- Adult beds aren’t safe for infants. A baby can become trapped and suffocate between the headboard slats, the space between the mattress and the bed frame, or the space between the mattress and the wall. A baby can also suffocate if a sleeping parent accidentally rolls over and covers the baby’s nose and mouth.

- Breast-feed your baby, if possible. Breast-feeding for at least six months lowers the risk of SIDS.

- What if I fall asleep while feeding my baby? Research shows that it is less dangerous to fall asleep with an infant in an adult bed than on a sofa or armchair. Before you start feeding your baby, think about how tired you are. If there’s even a slight chance you might fall asleep while feeding, avoid couches and armchairs. These surfaces can be very dangerous places for babies, especially when adults fall asleep with infants while on them. If you think you might fall asleep while feeding your baby in an adult bed, remove all soft items and bedding from the bed before you start feeding to reduce the risk of SIDS, suffocation, and other sleep-related causes of death.

- Don’t use baby monitors and other commercial devices that claim to reduce the risk of SIDS. The American Academy of Pediatrics discourages the use of monitors and other devices because of ineffectiveness and safety issues.

- Offer a pacifier. Sucking on a pacifier without a strap or string at naptime and bedtime might reduce the risk of SIDS. One caveat — if you’re breast-feeding, wait to offer a pacifier until your baby is 3 to 4 weeks old and you’ve settled into a nursing routine. If your baby’s not interested in the pacifier, don’t force it. Try again another day. If the pacifier falls out of your baby’s mouth while he or she is sleeping, don’t pop it back in.

- Immunize your baby. There’s no evidence that routine immunizations increase SIDS risk. Some evidence indicates immunizations can help prevent SIDS.

Can my baby choke if placed on the back to sleep?

The short answer is no. Research shows that the back sleep position carries the lowest risk of SIDS. Research also shows that babies who sleep on their backs are less likely to get fevers, stuffy noses, and ear infections. The back sleep position makes it easier for babies to look around the room and to move their arms and legs.

Healthy babies naturally swallow or cough up fluids—it’s a reflex all people have. Babies may actually clear such fluids better when sleeping on their backs because of the location of the opening to the lungs in relation to the opening to the stomach. There has been no increase in choking or similar problems for babies who sleep on their backs.

When the baby is in the back sleep position, the trachea (tube to the lungs) lies on top of the esophagus (tube to the stomach). Anything regurgitated or refluxed from the stomach through the esophagus has to work against gravity to enter the trachea and cause choking. When the baby is sleeping on its stomach, such fluids will exit the esophagus and pool at the opening for the trachea, making choking much more likely.

Cases of fatal choking are very rare except when related to a medical condition. The number of fatal choking deaths has not increased since back sleeping recommendations began. In most of the few reported cases of fatal choking, an infant was sleeping on his or her stomach.

What if my baby can’t get used to sleeping on his or her back?

The baby’s comfort is important, but safety is more important. Parents and caregivers should place babies on their backs to sleep even if they seem less comfortable or sleep more lightly than when on their stomachs.

A baby who wakes frequently during the night is actually normal and should not be viewed as a “poor sleeper.”

Some babies don’t like sleeping on their backs at first, but most get used to it quickly. The earlier you start placing your baby on his or her back to sleep, the more quickly your baby will adjust to the position.

Is it okay if my baby sleeps on his or her side?

No. Babies placed to sleep on their sides are at increased risk for SIDS. For this reason, babies should sleep fully on their backs for naps and at night to reduce the risk of SIDS.

If my baby rolls onto his or her stomach during sleep, do I need to put my baby in the back sleep position again?

No. Rolling over is an important and natural part of your baby’s growth. Most babies start rolling over on their own around 4 to 6 months of age. If your baby rolls over on his or her own during sleep, you do not need to turn the baby back over onto his or her back. The important thing is that your baby start every sleep time on his or her back to reduce the risk of SIDS, and that there is no soft objects, toys, crib bumpers, or loose bedding under baby, over baby, or anywhere in baby’s sleep area.

Can another caregiver or grandparents place my baby to sleep on his or her stomach for naptime?

No. Babies who usually sleep on their backs, but who are then placed to sleep on their stomachs, like for a nap, are at very high risk for SIDS. So it is important for everyone who cares for babies to always place them on their backs to sleep, for naps and at night, to reduce the risk of SIDS.

Are there times when my baby should be on his or her stomach?

Yes, your baby should have plenty of Tummy Time when he or she is awake and when someone is watching. Supervised Tummy Time helps strengthen your baby’s neck and shoulder muscles, build motor skills, and prevent flat spots on the back of the head.

What is Tummy Time?

Tummy time describes the times when you place your baby on his or her stomach while your baby is awake and someone is watching 9.

Tummy time is important because it 9:

- Helps prevent flat spots on the back of your baby’s head

- Makes neck and shoulder muscles stronger so your baby can start to sit up, crawl, and walk

- Improves your baby’s motor skills (using muscles to move and complete an action)

From the day they come home, babies benefit from 2 to 3 tummy time sessions each day for a short period of time (3 to 5 minutes). As the baby grows and shows enjoyment of tummy time, you can lengthen the sessions. Tummy time prepares babies for the time when they will be able to slide on their bellies and crawl. As babies grow older and stronger they will need more time on their tummies to build their own strength for sitting up, rolling over, crawling, and walking.

Tummy Time Tips

These suggestions1 can help you and your baby enjoy tummy time 9:

- Spread out a blanket in a clear area of the floor for tummy time.

- Try short tummy time sessions after a diaper change or after your baby wakes from a nap.

- Put a toy or toys within your baby’s reach during tummy time to help your baby learn to play and interact with his or her surroundings.

- Ask someone you trust to sit in front of your baby during tummy time to encourage interaction and bonding.

- As your baby gets older, your tummy time sessions can last longer, and you can have them more often throughout the day.

Will my baby get flat spots on the back of the head from sleeping on his or her back?

Pressure on the same part of the baby’s head can cause flat spots if babies are laid down in the same position too often or for too long a time. Such flat spots are usually not dangerous and typically go away on their own once the baby starts sitting up. The flat spots also are not linked to long-term problems with head shape. Making sure your baby gets enough Tummy Time is one way to help prevent these flat spots. Limiting the time spent in car seats, once the baby is out of the car, and changing the direction the infant lays in the sleep area from week to week also can help to prevent these flat spots.

In addition to tummy time, parents and caregivers can try these other ways to help prevent flat spots from forming on the back of baby’s head:

- Hold your baby upright when he or she is not sleeping. This is sometimes called “cuddle time.”

- Limit the amount of time your baby spends in car seats, bouncers, swings, and carriers.

- Change the direction your baby lies in the crib from one week to the next—for example, have your baby’s feet point toward one end of the crib one week, and then have the feet point toward the other end of the crib the next week.

Is a baby-sized cardboard box a safe alternative infant sleep surface?

Currently, the American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on SIDS indicates that there is not yet enough evidence to say anything about the potential benefit or dangers of using cardboard boxes, wahakuras, or pepi-pods.

A firm and flat sleep area that is made for infants, like a safety-approved* crib or bassinet, and is covered by a fitted sheet with no other bedding or soft items in the sleep area is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics to reduce the risk of SIDS and other sleep-related causes of infant death. Keeping baby in your room and close to your bed, ideally for baby’s first year, but at least for the first 6 months is also recommended by the AAP. Room sharing reduces the risk of SIDS. Having a separate safe sleep surface for baby reduces the likelihood of suffocation, entrapment, and strangulation.

*A crib, bassinet, portable crib, or play yard that meets the safety standards of the Consumer Product Safety Commission is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on SIDS. For information on crib safety, go to https://www.cpsc.gov

Why shouldn’t I use crib bumpers in my baby’s sleep area?

Bumper pads and similar products that attach to crib slats or sides are often used with the intent of protecting infants from injury. However, evidence does not support using crib bumpers to prevent injury. In fact, crib bumpers can cause serious injuries or death. Keeping them out of your baby’s sleep area is the best way to avoid these dangers.

Before crib safety was regulated, the spacing between the slats of the crib sides could be any width, which posed a danger to infants if they were too wide. Parents and caregivers used padded crib bumpers to protect infants. Now that cribs must meet safety standards, the slats don’t pose the same dangers. As a result, the bumpers are no longer needed.

Can I swaddle my baby to reduce the risk of SIDS?

There is no evidence that swaddling reduces SIDS risk. In fact, swaddling can increase the risk of SIDS and other sleep-related causes of infant death if babies are placed on their stomachs for sleep or roll onto their stomachs during sleep.

If you decide to swaddle your baby, always place baby fully on his or her back to sleep. Stop swaddling baby once he or she starts trying to roll over.

I saw a product being promoted to prevent SIDS and keep my baby in the right position during sleep. Can I use it to prevent SIDS?

There is currently no known way to prevent SIDS, nor are there any products that can prevent SIDS. Evidence does not support the safety or effectiveness of wedges, positioners, or other products that claim to keep infants in a specific position or to reduce the risk of SIDS, suffocation, or reflux. In fact, many of these products are associated with injury and death, especially when used in baby’s sleep area.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other organizations warn against using these products because of the dangers they pose to babies. Avoid products that go against safe sleep recommendations, especially those that claim to prevent or reduce the risk of SIDS. For more info go here: https://www.cpsc.gov/Newsroom/News-Releases/2010/Deaths-prompt-CPSC-FDA-warning-on-infant-sleep-positioners

Sudden infant death syndrome treatment

There’s no treatment for sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS. But there are ways to help your baby sleep safely. For the first year, always place your baby on his or her back to sleep. Use a firm mattress and avoid fluffy pads and blankets. Remove all toys and stuffed animals from the crib, and try using a pacifier. Don’t cover a baby’s head, and make sure your baby doesn’t get too hot. Your baby can sleep in your room, but not in your bed. Breast feeding for at least six months lowers the risk of SIDS. Vaccine shots to protect your baby from diseases may also help prevent SIDS.

References- Trachtenberg, F. L., Haas, E. A., Kinney, H. C., Stanley, C., & Krous, H. F. (2012). Risk factor changes for sudden infant death syndrome after initiation of Back-to-Sleep campaign. Pediatrics, 129(4), 630-638. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1419 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1419

- Fast Facts About SIDS. https://safetosleep.nichd.nih.gov/safesleepbasics/SIDS/fastfacts

- Kochanek, K.D., Murphy, S.L., Xu, J.Q., & Arias, E. (2019). Deaths: Final data for 2017. National Vital Statistics Reports, 68(9). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_09-508.pdf?deliveryName=USCDC_371-DM3857

- Panigrahy, A., et al. (2000). Decreased serotonergic receptor binding in rhombic lip-derived regions of the medulla oblongata in the SIDS. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 59, 377-384.

- The Triple-Risk Model. Adapted from “A perspective on neuropathologic findings in victims of the sudden infant death syndrome: the triple-risk model,” by J. J. Filiano & H. C. Kinney, 1994, Biology of the Neonate, 65(3-4), 194-197.

- Opdal, S. H., & Rognum, T. O. (2004). The sudden infant death syndrome gene: Does it exist? Pediatrics, 114(4), 506-512.

- Siri H. Opdal and Torleiv O. Rognum. The Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Gene: Does It Exist? Pediatrics. 2004 Oct;114(4):e506-12. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/114/4/e506.full.pdf

- Arnestad, M., Andersen, M., Vege, A., & Rognum, T. O. (2001). Changes in the epidemiological pattern of sudden infant death syndrome in southeast Norway, 1984–1998: Implications for future prevention and research. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 85, 108–115.

- Back to Sleep, Tummy to Play. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/baby/sleep/Pages/Back-to-Sleep-Tummy-to-Play.aspx