Symphysis pubis dysfunction

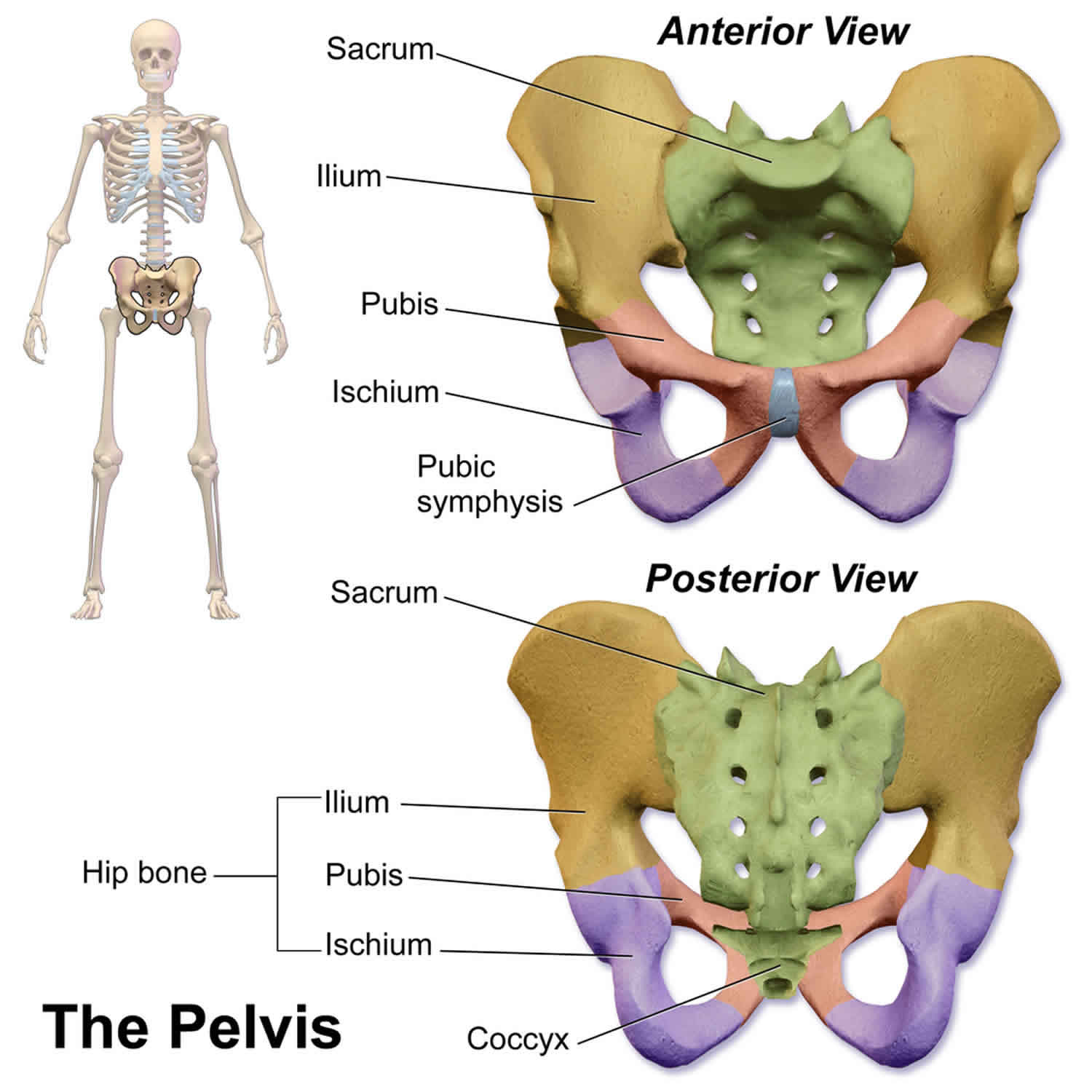

Symphysis pubis dysfunction (SPD) now called pelvic girdle pain, is a term describing pelvic pain in pregnancy 1. Symphysis pubis dysfunction is also known as peripartum pelvic pain, pregnancy-related pelvic pain, pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain, anterior or posterior pelvic pain, and pubic symphysis dysfunction. The pelvic girdle is a ring of bones around your body at the base of your spine (Figure 1). Symphysis pubis dysfunction or pelvic girdle pain, is pain in the front and/or the back of your pelvis that can also affect other areas such as the hips or thighs 2. It can affect the sacroiliac joints at the back and/or the symphysis pubis joint at the front 2. Pain when you are walking, climbing stairs and turning over in bed are common symptoms of SPD. SPD is more common later in pregnancy. SPD or pelvic girdle pain can be mild to severe but is treatable at any stage in pregnancy and the sooner it is treated, the more likely you are to feel better. Early diagnosis and treatment can relieve your pain. Treatment is safe at any stage during or after pregnancy.

The pubic symphysis is a fibrocartilaginous joint that sits between and joins the left and right superior rami of the pubic bones (Figure 1). The symphysis pubis joint holds the two innominate bones of the pelvis together and keeps them steady during activity. The pubic symphysis joint is further strengthened by external oblique fibres and the rectus abdominus muscle. Of the four ligaments enveloping the joint, the inferior or arcuate ligament is strongest and contributes most to joint stability but, together, all four neutralize shear and tensile stresses. The non pregnant woman’s symphysis pubis gap is 4–5 mm and it is normal for it to widen 2–3 mm, without discomfort, during the last trimester of pregnancy. This increases the diameters of the pelvic brim and cavity outlet to facilitate delivery of the fetus. The average symphysis pubis gap during the last two months of pregnancy is 7.7 mm with a range of 3–20 mm; 24% of women have a gap greater than 9 mm 3.

Symphysis pubis dysfunction or SPD occurs where the joint becomes sufficiently relaxed to allow instability in the pelvic girdle. In severe cases of SPD the symphysis pubis may partially or completely rupture. Where the gap increases to more than 10 mm this is known as diastasis of the symphysis pubis (DSP) 4.

SPD is a relatively common and debilitating condition affecting pregnant women. Symphysis pubis dysfunction or SPD is painful and can have a significant impact on your mobility and your quality of life, which can lead to potentially serious complications such as depression. Symphysis pubis dysfunction has been long recognized as an obstetrical condition in the literature but, until recently, there has been a lack of clinical interest 5. It is often confused with diastasis pubis (a separated symphysis pubis of more than 10 mm, or symphysiolysis), pelvic rupture (rupture of the symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joints simultaneously, which is extremely rare), and even osteitis pubis (partial or complete rupture of the symphysis pubis and requires aggressive treatment) 6. The disability related to symphysis pubis pain in pregnancy can vary from mild to severe, but is significant and any therapy that can help to reduce the discomfort is a welcome possibility 7.

The onset of pregnancy-related SPD can vary, with 74% in a first pregnancy and 12% in the first trimester, 34% in the second trimester and 52% in the third trimester 8. Women who develop SPD during pregnancy generally have a good prognosis, as delivery is usually curative. Most women’s pain regresses over the first 1–6 months post partum, with 25% having pain 4 months post partum and only a small number after 12 months 8. The exception to this are patients who may develop SPD after a traumatic delivery, which is approximately 1–17.4% of women 8. One study reported that non-invasive Doppler imaging of asymmetric laxity of the sacroiliac joints in women with moderate to severe pelvic pain in pregnancy can help to predict persistent pain postpartum (by three times) 9. It has also been found that the higher intensity of pain reported during pregnancy and an earlier onset were predictive of pelvic pain persisting post partum 9. The rates of reoccurrence have been reported between 41–77%, including 85% with a new pregnancy, 53–72% with menstruation, 22% with breast feeding 5.

Can SPD harm my baby?

No. Although symphysis pubis dysfunction can be very painful for you, it will not harm your baby.

Can I have a vaginal birth?

Yes. Most women with pelvic pain in pregnancy can have a normal vaginal birth.

Make sure the team looking after you in labour know you have SPD or pelvic girdle pain. They will ensure your legs are supported, help you to change position and help you to move around.

You may find a birthing pool helps to take the weight off your joints and allows you to move more easily. All types of pain relief are possible, including an epidural.

Do I need to have a caesarean section?

A caesarean section (C-section) will not normally be needed for SPD or pelvic girdle pain. There is no evidence that a caesarean section helps women with SPD or pelvic girdle pain and it may actually slow down your recovery.

Will I need to have labor started off (be induced) early?

Going into labor naturally is better for you and your baby. Most women with SPD or pelvic girdle pain do not need to have labour started off. Being induced carries risks to you and your baby, particularly if this is before your due date. Your midwife or obstetrician will talk to you about the risks and your options.

What happens after the birth of my baby?

SPD or pelvic girdle pain usually improves after birth although around 1 in 10 women will have ongoing pain. If this is the case, it is important that you continue to receive treatment and take regular pain relief. If you have been given aids to help you get around, keep using them until the pain settles down.

If you have had severe SPD or pelvic girdle pain, you should take extra care when you move about. Ask for a room where you are near to toilet facilities, or an en-suite room if available. Aim to become gradually more mobile. You should continue treatment and take painkillers until your symptoms are better.

If your pain persists, seek advice from your family doctor, who may refer you to another specialist to exclude other causes such as hip problems or hypermobility syndrome.

Will it happen in my next pregnancy?

If you have had SPD or pelvic girdle pain, you are more likely to have it in a future pregnancy. Making sure that you are as fit and healthy as possible before you get pregnant again may help or even prevent it recurring. Strengthening abdominal and pelvic floor muscles makes it less likely that you will get SPD or pelvic girdle pain in the next pregnancy.

If you get it again, treating it early should control or relieve your symptoms.

Is there anything else I need to know?

Pregnant women have a higher risk of developing blood clots in the veins of their legs compared with women who are not pregnant. If you have very limited mobility, the risk of developing blood clots is increased. You will be advised to wear special stockings (graduated elastic compression stockings) and may need to have injections of heparin to reduce your risk of blood clots.

SPD during pregnancy causes

The three joints in the pelvis work together and normally move slightly. SPD or pelvic girdle pain is usually caused by the joints moving unevenly, which can lead to the pelvic girdle becoming less stable and therefore painful. As your baby grows in your womb, the extra weight and the change in the way you sit or stand will put more strain on your pelvis. You are more likely to have SPD or pelvic girdle pain if you have had a back problem or have injured your pelvis in the past or have hypermobility syndrome, a condition in which your joints stretch more than normal.

Theoretical causes of SPD 6:

- biomechanical strains of the pelvic ligaments and associated hyperlordosis,

- anatomical pelvic variations,

- metabolic (calcium) and hormonal (relaxin and pro-gesterone) changes leading to ligamentous laxity,

- pathological weakening of the joint,

- tearing of the fibrocartilagenous disc during delivery,

- narrowing, sclerosis and degeneration of the joint,

- muscle weakness

- increased fetal and pregnancy-related weight gain.

Risk factors for developing symphysis pubis dysfunction

Predisposing factors for SPD and pelvic pain 10:

- genetics,

- family history,

- personal pregnancy history,

- early menarche,

- oral contraceptive use,

- multiparity,

- high weight,

- high levels of stress,

- low job satisfaction,

- history of low back pain,

- previous pelvic or back pathology or trauma,

- history of back or pelvic injury,

- lack of regular exercise (including long-distance running specifically),

- hypermobility,

- macrosomia or post-term delivery in pregnancy in labour,

- postpartum breast feeding

- neonatal developmental hip dysplasia.

SPD during pregnancy symptoms

SPD or pelvic girdle pain is more common later in pregnancy.

Symptoms of SPD include:

- “shooting” pain in the symphysis pubis;

- clicking or grinding in the pelvic area;

- pain in the pubic region, lower back, hips, groin, thighs or knees;

- radiating pain into the lower abdomen, back, groin, perineum, thigh, and/or leg;

- pain made worse by movement, for example:

- walking on uneven surfaces/rough ground or for long distances

- moving your knees apart, like getting in and out of the car

- standing on one leg, like climbing the stairs, dressing or getting in or out of the bath

- rolling over in bed

- during sexual intercourse.

- pain with activities of daily living, including bending forward, standing on one leg, rising from a chair, go up or down stairs, turning in bed;

- pain relieved by rest;

- clicking, snapping or grinding heard or felt within the symphysis pubis;

- painful sexual intercourse (dyspareunia);

- occasional difficulty voiding;

- unmotivated fatigue 8.

Symptoms commonly disappear shortly after giving birth. However, some women can suffer for several months afterwards and in a few cases pain can persist for much longer. At six months postnatally the reported proportion of women with classic SPD symptoms varies from 0–25% 11. The degree of discomfort often causes the woman significant difficulty in caring for her family and can lead to social isolation. She is also at greater risk of developing severe anxiety and depression 12.

Signs of SPD include:

- tenderness over the pubic symphysis and/or sacroiliac joints;

- palpable gap in the pubic symphysis;

- suprapubic edema and swelling;

- positive Trendelenberg’s sign on one or both sides;

- positive Lesague’s sign on one or both sides;

- Patrick test may be positive;

- waddling gait with short steps;

- paravertebral, gluteal, and piriformis muscles and sacrotuberous ligament tenderness 5.

- self-administered tests (alternative to the painful but highly sensitive and specific symphysis pubis palpation): pain drawing and a painful MAT-test (patient abducts and adducts the hip, simulating the movement of pulling a mat). These have shown the same results as palpation without the increased discomfort 13.

SPD during pregnancy diagnosis

Tell your midwife or doctor about your pain. You should be offered an appointment with a physiotherapist who will make an assessment to diagnose SPD or pelvic girdle pain. This will involve looking at your posture and your back and hip movements and ruling out other causes of pelvic pain.

Tenderness over the symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joints are the commonest clinical signs of SPD or pelvic girdle pain. The range of hip movements may be limited by pain, particularly during abduction and lateral rotation. A waddling gait may result from a tendency of the gluteus medius to lose its abductor function,which is further exaggerated by the natural lumbar lordosis of pregnancy. Fry et al. 14 explain how the clinician may be able to palpate the widening of the symphysis pubis but stress that the woman’s own description of discomfort is sufficient to diagnose SPD or pelvic girdle pain; this opinion is also supported by Wellock 15.

Continuous or disabling pelvic pain, especially when turning in bed, walking, climbing stairs, rising from a chair, standing on one leg or weight bearing unilaterally, is typical. In determining the presence of this condition it is helpful to conduct further examination assisted by an obstetric physiotherapist. No single test is diagnostic. However, the following tests 16 for symphyseal pain in pregnancy have high sensitivity, specificity and inter-examiner reliability (Kappa coefficient). Palpation of the entire anterior surface of the symphysis pubis, with the woman supine, typically elicits pain that persists for more than five seconds after removal of the examiner’s hand (60% sensitivity, 99% specificity, 0.89 Kappa coefficient). Commonly, when the woman stands on one leg she is unable to maintain the pelvis in a horizontal plane and the opposite buttock drops (Trendelenburg’s sign; 60% sensitivity, 99% specificity, 0.63 Kappa coefficient). A Patrick’s FABER sign may be elicited. With one iliac spine held in a fixed position by the examiner, the woman lies in a supine position, placing her opposite heel on the ipsilateral knee with the leg falling passively outwards. The test is positive if pain occurs in either sacroiliac joint (40% sensitivity, 99% specificity, 0.54 Kappa coefficient).

On palpation, anteroposterior or superoinferior displacement of the upper border of the pubic symphysis or pubic tubercle can be felt. Active straight leg raising (Lesague’s sign) may be limited or

impossible to perform, yielding pain as well as palpable displacement of the symphysis pubis joint. This is less painful if the pelvis is stabilised by manual compression and the active straight leg raising test then becomes easier to perform. Bilateral trochanteric compression may also increase pain.

Other tests shown to have high reproducibility include the pelvic girdle relaxation test for pain at the symphysis with the woman standing on one leg with the other hip flexed to 90º; and testing for unilateral or bilateral tenderness of the iliopsoas muscle, sacrotuberous ligaments and sacroiliac joints 17.

The differential diagnosis includes lumbago and sciatica, urinary tract infection, osteitis pubis and osteomyelitis. These need to be firmly excluded to ensure the diagnosis of SPD or pelvic girdle pain.

Imaging is the only way to confirm diastasis of the symphysis pubis. It may also prove a useful tool for monitoring progress of SPD or pelvic girdle pain and assisting in the exclusion of other differential diagnoses. Plain radiographs (anteroposterior view in the ‘flamingo position’ or single leg standing position to assess vertical mobility: computerized tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound scans have all been used to assess the misalignment of the pelvic bones 18.

Two small Swedish studies 19, 20 have shown ultrasound to be simple, safe and as precise as X-rays at assessing symphyseal widening in pregnancy and the puerperium but without the concerns of fetal radiation exposure. However, several studies have failed to show any correlation between the symphyseal gap and severity of SPD or pelvic girdle pain 21. More studies using ultrasound are needed to investigate further joint widening in this condition.

SPD during pregnancy treatment

For most women, early diagnosis and treatment should stop symptoms from getting worse, relieve your pain and help you continue with your normal everyday activities. It is therefore very important that you are referred for treatment early. SPD or pelvic girdle pain is not something you just have to ‘put up with’ until your baby is born.

Conservative management of SPD can include pelvic support belts, which have been studied in the literature with contradictory results. One paper reported that belts are no better than exercise alone and recommended that patients strengthen their musculature for longer term stability instead 22. Subjects were given an exercise booklet with un-specified exercises to be performed 3 times daily using a logbook and had a single demonstration 23. Another study recommended 50 Newton of tension and a higher belt position (just caudal to the anterior superior iliac spines) to resist pelvic shear 24. Pelvic belts have also been found to significantly decrease mobility in the sacroiliac joints 25. A pelvic support belt has also been theorized to be most helpful in the later stages of pregnancy, when deep abdominal muscle activation is not possible, since the belt provides a “locked in” position to decrease the hypermobility in the pelvis that is associated with pregnancy related changes 26. It has been recommended to do muscular core training postpartum to provide this intrinsic stability 26.

Figure 2. Pregnancy pelvic support belt

Other treatments include elbow crutches, a walking frame or wheelchair may have to be used when mobility is compromised in extremely painful cases 5. Simple analgesics can be recommended by the obstetrician or midwife 5. TENS, rest, ice, heat, massage, acupuncture and mobilization or manipulation help to reduce discomfort as well 10. One retrospective case report of osteopathic treatment of SPD showed positive results (including soft tissue massage, manipulation the thoracolumbar junction, muscle energy and articulatory mobilization technique to the symphysis pubis, L5 and left innominate and strain-counterstrain technique) 26. Chiropractic treatment (including interferential therapy, massage, gentle lateral recumbent mobilization, home cryotherapy and exercises) has been shown to be beneficial and effective in treating SPD in one study that surveyed SPD patients and their chiropractors 27. Postural and ergonomic advice, use of a wedge-shaped pillow, and self-help group information may also help 5. In rare extreme cases of SPD and/or symphysis pubis separation, referral to an orthopaedic surgeon for suturing of the symphysis pubis or a pubic wedge resection may be a last resort treatment 5.

Rehabilitation exercise during pregnancy should include isometric and non-isometric exercises with short arc movements of the lower limbs and the avoidance of one-sided movement combinations to prevent aggravating symptoms 28. Also, supporting musculature should be targeted locally and globally to support the entire pelvis and low back, including aerobic conditioning, light stretching, relaxation exercises and ergonomic advice 29. Water aerobics have been found to help reduce pain and sick days in pregnant women with low back and pelvic pain 30. Much of the research states that individualized physical therapy has shown to lead to better functional outcomes and reduction in pain, but many of the articles do not specify what exercises are prescribed, the dose and the reasons they are chosen 30. One article prescribed three pelvic girdle stabilizing exercises (using a ball between the knees in sitting, standing and kneeling position), plus four strengthening exercises (lateral pulls, standing leg-press, sit-down rowing and curl-ups), as well as stretching of the hamstrings, hip flexors and calf muscles to pregnant participants 7. Unfortunately they found no difference in any of their three groups (information, home exercise and in clinic exercise groups) during pregnancy or on follow-up 7.

Post-partum rehabilitation exercise prescription recommendations include: restoring hip stability, lumbo-pelvic stability and motor control by training the transverse abdominis and multifidus muscles, activating the related muscle-fascia-tendon slings and pelvic floor muscles, with slow progressions within patient tolerance 6. These muscle slings connect with ligaments and fascia to contribute to stability and create a compressive “force closure” on the pelvis 31. This differs from “form closure” of the closely fitting joint surfaces that help to allow the pelvis to resist shear forces 31. Transversus abdominis contraction has been shown to decrease the laxity of the sacroiliac joint in non-pregnant women, while women with pelvic pain three years postpartum have been found to have poor muscle function 25. Stuge et al. 31 used a specific stabilization exercise program to improved functional status and reduce pain in women with postpartum pelvic pain. The program included specific transversus abdominis training during daily activities with multifidus coactivation, as well as gluteus maximus, abdominal obliques, erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, hip abductors and adductors training 31. The participants exercised 30–60 minutes, 10 repetitions per exercise, 3 days per week for 18–20 weeks 31. The success of this program was helped by individual training, the use of a training diary, as well as having home equipment 31. The authors found that the participants who did the specific exercises had less pain, improved function and a better quality of life 6.

SPD pain relief

The following simple measures may help:

- keeping active but also getting plenty of rest

- standing tall with your bump and bottom tucked in a little

- changing your position frequently – try not to sit for more than 30 minutes at a time

- sitting to get dressed and undressed

- putting equal weight on each leg when you stand

- trying to keep your legs together when getting in and out of the car

- lying on the less painful side while sleeping

- keeping your knees together when turning over in bed

- using a pillow under your bump and between your legs for extra support in bed.

You should avoid anything that may make your symptoms worse, such as:

- lifting anything heavy, for example heavy shopping

- going up and down the stairs too often

- stooping, bending or twisting to lift or carry a toddler or baby on one hip

- sitting on the floor, sitting twisted, or sitting or standing for long periods

- standing on one leg or crossing your legs.

Your physiotherapist will suggest the right treatment for you. This may include:

- advice on avoiding movements that may be aggravating the pain. You will be given advice on the best positions for movement and rest and how to pace your activities to lessen your pain.

- exercises that should help relieve your pain and allow you to move around more easily. They should also strengthen your abdominal and pelvic floor muscles to improve your balance and posture and make your spine more stable.

- manual therapy (hands-on treatment) to the muscles and joints by a physiotherapist, osteopath or chiropractor who specialises in SPD in pregnancy. They will give you hands-on treatment to gently mobilise or move the joints to get them back into position, and help them move normally again. This should not be painful.

- warm baths, or heat or ice packs

- hydrotherapy

- acupuncture

- a support belt or crutches.

I’ve tried these measures but I’m still in pain. What are my options?

Being in severe pain and not being able to move around easily can be extremely distressing. Ask for help and support during your pregnancy and after the birth. Talk to your midwife and doctor if you feel you are struggling. If you continue to have severe pain or limited mobility, it is worth considering:

- regular pain relief. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is safe in pregnancy and may help if taken in regular doses. If you need stronger pain relief, your doctor will discuss this with you.

- aids such as crutches or a wheelchair for you to use on a short-term basis. Your physiotherapist will be able to advise you about this. Equipment such as bath boards, shower chairs, bed levers and raised toilet seats may be available.

- changes to your lifestyle such as getting help with regular household jobs or doing the shopping.

- if you work, talking to your employer about ways to help manage your pain. You shouldn’t be sitting for too long or lifting heavy weights. You may want to consider shortening your hours or stopping work earlier than you had planned if your symptoms are severe.

If you are in extreme pain or have very limited mobility, you may be offered admission to the antenatal ward where you will receive regular physiotherapy and pain relief. Being admitted to hospital every now and then may help you to manage your pain.

References- Howell ER. Pregnancy-related symphysis pubis dysfunction management and postpartum rehabilitation: two case reports. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56(2):102–111. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3364059

- Pelvic girdle pain and pregnancy. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/patients/patient-information-leaflets/pregnancy/pi-pelvic-girdle-pain-and-pregnancy.pdf

- Philipp E, Setchell M. The bones, joints and ligaments of the female pelvis. In: Philipp E, Setchell M, editors. Scientific Foundations of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 1991. p. 80.

- Jain S, Eedarapalli P, Jamjute P, Sawdy R. Symphysis pubis dysfunction: a practical approach to management. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2006;8:153–158.

- Leadbetter RE, Mawer D, Lindow SW. Symphysis pubis dysfunction: a review of the literature. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Medicine. 2004;16:349–354.

- Borg-Stein J, Dugan SA. Musculoskeletal disorders of pregnancy, delivery and postpartum. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18(3):459–476.

- Nilsson-Wikmar L, Holm K, Oijerstedt R, Harms-Ringdahl K. Effect of three different physical therapy treatments on pain and activity in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: a randomized clinical trial with 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up postpartum. Spine. 2005;30(8):850–856.

- Leadbetter RE, Mawer D, Lindow SW. The development of a scoring system for symphysis pubis dysfunction. J Obstetrics Gynecology. 2006;26(1):20–23.

- Damen L, Buyruk HM, Guler-Uysal F, Lotgering FK, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ. The prognostic value of asymmetric laxity of the sacroiliac joints in pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Spine. 2002;27(24):2820–2824.

- Karadeli E, Uslu N. Postpartum sacral fracture presenting as lumbar pain. J Women’s Health. 2009;18(5):663–665.

- Coldron Y. Margie Poldon Memorial lecture: ‘Mind the gap!’Symphysis pubis dysfunction revisited. Journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Women’s Health 2005;96:3–15.

- Wainwright M, Fishburn S, Tudor-Williams N, Naoum H, GarnerV. Symphysis pubis dysfunction: improving the service. British Journal of Midwifery 2003;11:664–7.

- Olsen MF, Gutke A, Elden H, Nordenman C, Fabricius L, Gravesen M, Lind A, Kjellby-Wendt G. Self-administered tests as a screening procedure for pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(8):1121–1129.

- Fry D, Hay-Smith J, Hough J, McIntosh J, Polden M, Shepherd J, et al. Symphysis pubis dysfunction. Physiotherapy 1997;83:41–2.

- WellockVK. The ever widening gap – symphysis pubis dysfunction. British Journal of Midwifery 2002;10:348–53.

- Albert H, Godskesen WJ. Evaluation of clinical tests used in classification procedures in pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain. Eur Spine J 2000;9:161–6.

- Hansen A, Jensen DV, Wormslev M, Minck H, Johansen S, Larsen EC, et al. Symptom-giving pelvic girdle relaxation in pregnancy. II: Symptoms and clinical signs. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999;78:111–15.

- Bjorklund K, Bergstrom S, Lindgren PG, Ulmsten U. Ultrasonographic measurement of the symphysis pubis: a potential method of studying symphyseolysis in pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1996;42:151–53.

- Coldron Y. Margie Poldon Memorial lecture: ‘Mind the gap!’ Symphysis pubis dysfunction revisited. Journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Women’s Health 2005;96:3–15.

- Bjorklund K, Bergstrom S, Nordstrom ML, Ulmsten U. Symphyseal distension in relation to serum relaxin levels and pelvic pain in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scan 2000;79:269–75.

- Bjorklund K, Nordstrom ML, Bergstrom S. Sonographic assessment of symphyseal joint distension during pregnancy and post partum with special reference to pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scan 1999;78:125–30.

- Depledge J, McNair PJ, Keal-Smith C, Williams M. Management of symphysis pubis dysfunction during pregnancy using exercise and pelvic support belts. Physical Therapy. 2005;85(12):1290–1300.

- Depledge J, McNair PJ, Keal-Smith C, Williams M. Management of symphysis pubis dysfunction during pregnancy using exercise and pelvic support belts (see Figure 2). Physical Therapy. 2005;85(12):1290–1300.

- Damen L, Spoor CW, Snijeders CJ, Stam HJ. Does a pelvic belt influence sacroiliac joint laxity? Clin Biomechanics. 2002;17(7):495–498.

- Mens JMA, Damen L, Snijeders CJ, Stam HJ. The mechanical effect of a pelvic belt in patients with pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Clin Biomechanics. 2006;21(2):122–127.

- Cassidy IT, Jones CG. A retrospective case report of symphysis pubis dysfunction in a pregnant woman. J Osteopath Med. 2002;5(2):83–86.

- Andrews C, Pedersen P. A study into the effectiveness of chiropractic treatment for pre- and postpartum women with symphysis pubis dysfunction. Eur J Chiro. 2003;48(3):77–95.

- Sanders SG. Dancing through pregnancy: activity guidelines for professional and recreational dancers. J Dance Med Sci. 2008;12(1):17–22.

- Mens JMA, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ. Diagonal trunk muscle exercises in peripartum pelvic pain: A randomized clinical trial. Physical Therapy. 2000;80(12):1164–1173.

- Stuge B, Hilde G, Vollestad N. Physical therapy for pregnancy-related low back and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(11):983–990.

- Stuge B, Laerum E, Kikesola G, Vollestad N. The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2004;29(4):351–359.