Testicular trauma

Testicular trauma is defined as any injury sustained by the testicle. Trauma to the testicle or scrotum can harm any of its contents. Testicular trauma can be divided into three broad categories based on the mechanism of injury: (1) blunt trauma, (2) penetrating trauma, and (3) degloving trauma 1. Such injuries are typically seen in males aged 15-40 years. Testicular trauma is relatively uncommon. Blunt trauma accounts for approximately 85% of cases, and penetrating trauma accounts for 15%. Acute scrotal swelling in children is often associated with testicular torsion, testicular rupture, hernia, epididymitis and direct testicular trauma 2. In a previous study testicular torsion, torsion of testicular appendages, and epididymitis were found to represent 94% of all final diagnoses in boys under the age of 17 years who were hospitalized for acute scrotal pain and swelling 3. Testicular torsion is when the testicle twists around, cutting off its blood supply. It’s rare, but when it does happen it’s often for no obvious reason. Occasionally torsion is brought on by a serious trauma to the testicles or strenuous activity. Testicular torsion is an emergency. Testicular torsion usually affects boys ages 12 to 18, so if you think it’s happening to you, go to the emergency room right away. If doctors fix a testicular torsion within 4 to 6 hours of the time the pain starts there’s usually no lasting damage to the testicles. But if a testicular torsion isn’t fixed within that timeframe, there’s a high chance of losing a testicle or having permanently reduced sperm production. Doctors sometimes fix a testicular torsion manually by untwisting the testicle. If that doesn’t work, they do a simple surgery.

The first sign of trauma to the testicle or scrotum is most often severe pain. Pain around the testicle may also be due to infection or swelling of the epididymis (“epididymitis”). Because the epididymis has a very thin wall, it easily becomes red and swollen by infection or injury. If not treated, in rare cases the blood supply to the testicle can get blocked. This can lead to loss of the testicle.

Men who suffer more than a minor injury to the scrotum should seek care by a urologist. Reasons to seek medical care are:

- any penetrating injury to the scrotum

- bruising and/or swelling of the scrotum

- trouble peeing or blood in the urine

- fevers after testicular injury

Though not linked to the injury, a large number of testicular tumors are found after minor injuries when men are more likely to carefully check their testicles. Many men don’t notice the painless, solid lump bulging from the smooth testicular cover until they have a reason to look. Even if you think this is a simple bruise, it’s a medical emergency. Testicular cancer caught early can often be cured. But tumors found late often need drawn-out treatment with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

Therefore, a thorough history and detailed physical examination are essential for an accurate diagnosis 1. Scrotal ultrasonography with Doppler flow evaluation is particularly helpful in determining the nature and extent of the injury. This is especially true in blunt trauma cases, given the difficulty of scrotal examination and the repercussions of missing a testicular rupture. The sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography in this situation has been reported to be 93.5% and 100%, respectively. However, in the setting of a clinically apparent hematocele (blood in the tunica vaginalis), some authors question the value of a ultrasonographic examination and feel prompt exploration is more appropriate 4. As many as 80% of hematoceles (blood in the tunica vaginalis) are associated with testicular rupture.

Penetrating testicular trauma usually requires scrotal exploration to determine the severity of testicular injury, to assess the structural integrity of the testis, and to control intrascrotal hemorrhage. If the tunica albuginea is violated, early surgical exploration, debridement, and closure of the tunica albuginea are necessary.

Blunt injuries are encountered more often than penetrating injuries and are usually unilateral, whereas penetrating injuries involve both testes in a third of cases. Most cases of blunt trauma to the testicles are minor and usually require only conservative therapy. However, in one study, Buckley and McAninch 5 reported that 46% of patients presenting with blunt scrotal trauma underwent surgical exploration and were found to have rupture of the tunica albuginea. Operative indications for blunt trauma are as follows:

- Suspicion of rupture

- Expanding hematomas

- Dislocation refractory to manual reduction

- Avulsion

- Scrotal degloving

However, a study by Chandra et al 4 has suggested that conservative management is an option in blunt trauma patients when ultrasonography demonstrates absence of hematocele, obvious testicular fracture planes, or disruption of the tunica albuginea. In a study of nonoperative management in seven adolescent boys who presented with testicular rupture 1 to 5 days after sustaining blunt scrotal trauma, Cubillos et al 6 reported that none of the patients required orchiectomy or developed atrophy at 6 months of follow-up. Further investigation is needed before such an approach can be recommended in children or adults.

I’ve noticed pain in my scrotum and testicle but I don’t remember any injury. What should I do?

There are many possible causes of scrotal or testicle pain, such as epididymitis, swelling of the testicle, and problems with other parts of the scrotum. You should be checked by a urologist to find the source.

I was hit by a knee during a basketball game and have since noticed a new lump in my scrotum. It doesn’t hurt, but should I do anything about it?

Like many young men, you’re likely checking yourself for the first time now that you’ve had a sporting injury. There’s a good chance that the lump or “new” mass you’ve just felt is a normal part of the anatomy (your epididymis). But it could be an injury or even testicular cancer. Any new lump should be checked at once by a trained urologist. With his/her skill, a urologist will ease your mind and point you to swift and proper treatment.

I’m 55 years old and noticed a lump in my scrotum after being hit in the groin during a pick-up game of baseball. Could this be testicular cancer, or am I too old for that?

Testicular cancer can show up at any age, though most cases are seen between 15 and 35 years of age. Any man with a new lump in his scrotum should see a urologist right away. Often, you won’t need any further tests because your urologist can make a diagnosis with a physical exam. He/she may also ask for an ultrasound, though. While some masses are safe (benign), many can be cancer (malignant). The good news is that testicular cancer caught early can be treated with good results. Don’t be afraid to call a urologist.

I noticed blood in my urine after being hit with a baseball. I don’t feel any lumps. Should I still report this to my doctor?

Absolutely. Blood in the urine that’s visible to the naked eye is almost always due to a urological problem. You need to see a doctor or urologist right away to find the reason.

What can I do to prevent injury to my testicles?

There are many common-sense steps you can take to lower your risk of testicular trauma. Wear a seat belt when driving a car. If you work around machinery that has exposed chains or belts, make sure your clothes are tucked in and loose belts or other items that can catch aren’t exposed. Wear a jock strap when playing sports. If the activity has a chance of rough contact (as in baseball, football, or hockey), use a hard cup.

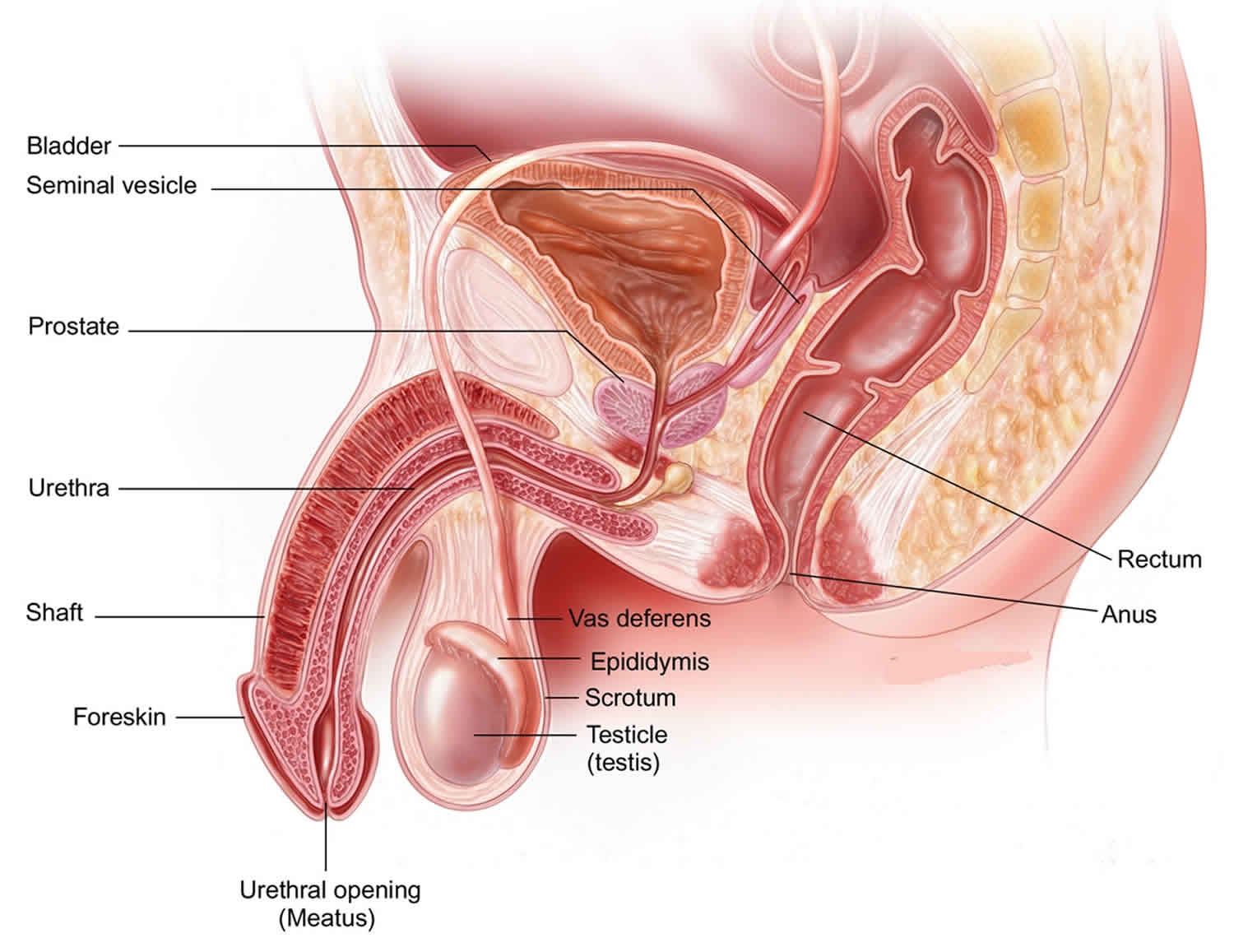

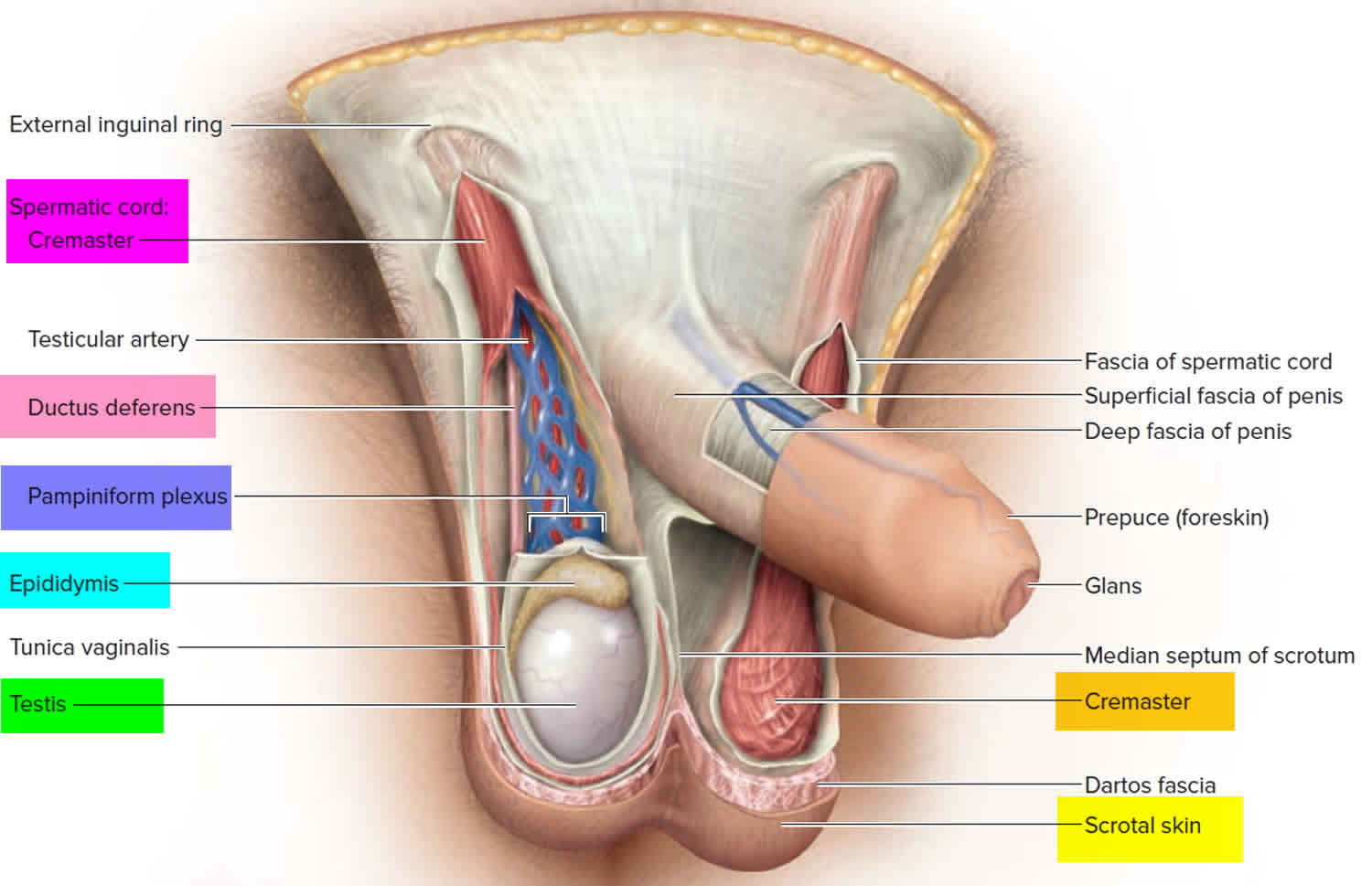

Testicles and scrotum anatomy

To properly evaluate and treat testicular injuries, a thorough knowledge of scrotal and testicular anatomy is required. The testicles are vital for reproduction and normal male hormones. Because they’re in the scrotum, which hangs outside the body, they don’t have muscles and bones to protect them like most organs have. This makes it easier for the testicles to be struck, hit, kicked, or crushed.

The outermost layer of the scrotum (the skin sac that hangs below the penis) is the scrotal skin. The next most superficial layer is the dartos muscle/fascia, which is contiguous with the Scarpa fascia of the abdomen, the Colles fascia of the perineum, and the dartos fascia of the penis. The dartos layer is followed by the external, middle, and internal spermatic fasciae, which are contiguous with the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversalis fasciae, respectively. The middle spermatic fascia forms the cremasteric muscle of the spermatic cord. In most cases, the testicle is tethered to the scrotum inferiorly by the gubernaculum.

The next layer is the tunica vaginalis, which is composed of an outer (parietal) layer and an inner (visceral) layer. The tunica albuginea is a tough, white, fibrous, capsulelike layer surrounding the seminiferous tubules of the testis. The visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis adheres to this layer.

The testis is enveloped by layers of white fibrous connective tissue called the tunica vaginalis and the tunica albuginea. The tunica albuginea is the visceral layer that covers the testis, and the tunica vaginalis is the parietal layer that lines the hydrocele sac. The tunica albuginea extends inward posteriorly to form the mediastinum testis, the point where vessels and ducts traverse the testicular capsule. The epididymis attaches posterolaterally.

The tunica albuginea is the layer that is violated during a testicular rupture. Approximately 50 kg of force is required to rupture the testicle. A tear in the tunica albuginea leads to extrusion of the seminiferous tubules and allows an intratesticular hemorrhage to escape into the tunica vaginalis. This is referred to as a hematocele. Disruption of the tunica vaginalis or extension to the epididymis leads to bleeding into the scrotal wall, resulting in a scrotal hematoma.

Two factors protect the testes from minor external trauma. First, a thin layer of serous fluid (ie, physiologic hydrocele) separates the tunica albuginea from the tunica vaginalis and allows the testis to slide freely within the scrotal sac. Second, the testes are suspended within the scrotum by the spermatic cord, allowing them to move freely within the genital area. In cases of penetrating trauma or severe blunt trauma, these protective features are insufficient to prevent injury to the testis proper.

Sperm cells are made in the testicle and travel to the epididymis, a rubbery gland along the back of the testicle. In the epididymis, thousands of sperm-making ducts from the testicle join to form a single coiled tube. Sperm stop briefly in the epididymis to mature before mixing with semen and leaving through a tube (the vas deferens) that joins with the urethra. The vas deferens is covered by a thick muscle wall. But the epididymis has a thin, fragile coating, and so is at higher risk for swelling or injury.

Blood supply to the testes is threefold:

- The testicular artery is the principal artery, arising from the aorta, just below the renal artery.

- The cremasteric artery is a branch of the inferior epigastric artery.

- The deferential artery is a branch of the superior vesical artery.

These 3 vessels collateralize and anastomose in the spermatic cord and near the epididymis.

Figure 1. Testicles and scrotum anatomy

Figure 2. Testicle anatomy

Testicular trauma causes

The most common cause of blunt testicular trauma is sports injuries. For example, a study of rugby players in Australia and New South Wales from 1980 to 1993 revealed 14 players with testicular injuries, with the most unfortunate losing both testicles.

However, the risk of sports-related testicular injury in US children is likely less than previously suspected. Wan et al 7 reviewed the National Pediatric Trauma Registry for all 50 states and referenced commonly played contact sports. Of 5,439 reported sports injuries, none were testicular injuries. The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness gives an “unqualified yes” to the question of whether or not a boy with only one testicle can play sports. Protective cups may be required in some instances.

The second most common cause of testicular trauma is a kick to the groin. Less common causes include motor vehicle accidents, falls, and straddle injuries.

The most common cause of penetrating testicular injuries is a gunshot wound to the genital area 8. Other causes include stab wounds, self-mutilation, animal bites (usually dog), and emasculation.

Degloving testicular injuries most commonly result from accidents incurred while operating heavy machinery (eg, industrial or farming accidents).

Blunt testicular trauma

Blunt testicular trauma refers to injuries sustained from objects applied with any significant force to the scrotum and testicles. This can occur with various types of activity. Examples include a kick to the groin or a baseball injury 9. One report even described testicular rupture from a paint ball injury 10. Also, one study reported an increased incidence of testicular calcifications in extreme mountain bikers over nonbikers, suggesting repeated testicular trauma in these individuals 11.

Blunt testicular injuries can be managed either medically or surgically, depending on the clinical presentation. Early surgical intervention for blunt trauma is associated with higher salvage rates (94% vs 79%).

Penetrating testicular trauma

Penetrating testicular trauma refers to injuries sustained from sharp objects or high-velocity missiles. Examples include gunshot and stab wounds.

Testicular rupture

Testicular rupture or fractured testis refers to a rip or tear in the tunica albuginea resulting in extrusion of the testicular contents. This can happen when the testicle receives a forceful direct blow or when the testicle is crushed against the pubic bone (the bone that forms the front of the pelvis), causing blood to leak into the scrotum. Testicular rupture, like testicular torsion and other serious injuries to the testicles, causes extreme pain, swelling in the scrotum, nausea, and vomiting. To fix the problem, surgery is necessary to repair the ruptured testicle.

Degloving testicular trauma

Degloving injuries or avulsion injuries are less common. With these, scrotal skin is sheared off, for example, when a testicle becomes trapped in heavy machinery.

Testicular dislocation

Testicular dislocation is an uncommon and sometimes easily overlooked event that refers to a testis that has been relocated from its orthotopic position to another location secondary to blunt trauma. Indirect inguinal hernias and atrophic testicles may be predisposing factors. Most cases of testicular dislocation are the result of motorcycle crashes, and one third involve both testicles. This is related to impact with the fuel tank, and the inguinal region is the most frequent site of displacement 12. Additional dislocation routes include the following:

- Pubic

- Preputial

- Acetabular

- Canalicular

- Penile

- Intra-abdominal

- Retrovesical

- Perineal

- Crural

Testicular dislocation is seen in less than 0.5% of cases of abdominal trauma. One retrospective review of emergency department records found that all instances were missed initially, even with CT scanning demonstrating an empty scrotum and displaced testis. The average delay in diagnosis was 19 days 13. Diagnosis of testicular dislocation should be followed by early treatment in the form of manual closed reduction. Surgical fixation is used if closed reduction is unsuccessful.

Genital self-mutilation

Genital self-mutilation is another potential source of testicular trauma. The offending patient is often psychotic, although nonpsychotic patients practicing autoeroticism and motivated yet desperate transsexuals may find themselves requiring an urgent urologic consultation. Most cases of genital self-mutilation involve men castrating themselves. If the patients seek care promptly and the testicles are vital, reimplantation may be considered.

Testicular trauma symptoms

Patients with testicular trauma typically present to the emergency department with a straightforward history of injury (eg, sports injury, kick to the groin, gunshot wound) soon after the event occurs.

Patients who have sustained severe blunt trauma usually exhibit symptoms of extreme scrotal pain, frequently associated with nausea and vomiting. When evaluating a patient with a clinical history of only minor trauma, do not overlook the possibility of testicular torsion or epididymitis. Physical examination often reveals a swollen, severely tender testicle with a visible hematoma. Scrotal or perineal ecchymosis may be present. Bilateral testicular examination and perineal examination should always be performed to rule out associated pathologies. However, because of the severe pain the patient experiences, performing a thorough examination is often difficult, and radiologic evaluation or surgical exploration may be required.

Most blunt testicular injuries are unilateral and isolated (ie, without other associated injuries). The absence of scrotal swelling and hematoma may indicate a relatively benign injury. Additional imaging tests or scrotal exploration is required if testicular rupture is suggested because of clinical findings or when a patient experiences pain out of proportion to the physical examination findings. Blunt trauma to the testes may manifest as a hematocele or a ruptured testis. The complete absence of pain in a patient with scrotal swelling and hematoma raises the possibility of testicular infarction or spermatic cord torsion.

For penetrating injuries, determine the entrance and exit sites of the wound. Up to 75% of men with penetrating injuries to the genitalia demonstrate additional associated injuries. Carefully examine the contralateral hemiscrotum and the perineal area. Rule out injuries to the contralateral testicle, bulbar urethra, and rectum. Also evaluate the femoral vessels, as major vascular insult in the thigh region is the most commonly reported associated injury. Although uncommon, vascular injury subsequently leading to an ischemic testis has been reported.

Using universal precautions when evaluating these injuries is important. One review of 40 men with penetrating trauma revealed that 38% tested positive for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or both. Furthermore, according to Cline et al 14 in 1998, 60% of these patients were legally intoxicated at the time of injury.

Screening urinalysis is an important adjunct to the physical examination to rule out urinary tract infection or epididymo-orchitis.

Scrotal ultrasonography with Doppler studies is valuable for diagnosing and staging testicular injuries. The presence of a disrupted tunica albuginea is pathognomonic for testicular rupture. A scrotal hematoma often has associated scrotal skin thickening.

Perform Doppler studies during the scrotal ultrasonography because they provide information on the vascular status of the testes. Blood flow to the testis indicates that the vascular pedicle is intact. An absence of flow implies that a torsion or devascularizing injury has occurred to the spermatic cord.

Other imaging studies, such as nuclear imaging or MRI, may be used to obtain additional information in equivocal cases. However, the definitive diagnosis of testicular rupture is made in the operating room, and time is a factor in testicular preservation. Scrotal exploration is truly the best diagnostic tool for any equivocal testicular trauma.

Indications for scrotal exploration include the following:

- Uncertainty in diagnosis after appropriate clinical and radiographic evaluations

- Clinical findings consistent with testicular injury

- Disruption of the tunica albuginea

- Absence of blood flow on sonograms with Doppler studies

Clinical hematoceles that are expanding or of considerable size (eg, ≥5 cm) should be explored. Collections of smaller size are also often explored, because that has been shown to allow for more optimal pain control and shorter hospital stays.

If the testis is fractured, testicular debridement and surgical closure of the tunica albuginea are necessary.

Penetrating testicular trauma usually requires exploration to ascertain the degree of injury, assess the integrity of the testis, and identify and control intratesticular hemorrhage.

Degloving injuries are another indication for operative evaluation and often require debridement. Skin closure may or may not be possible in the acute setting.

The absence of blood flow on ultrasonography may represent spermatic cord torsion, avulsion, or infarction.

Testicular trauma complications

Complications associated with untreated testicular injuries are significant and include the following:

- Testicular infarction

- Testicular torsion

- Testicular or epididymal abscess

- Infertility

- Testicular necrosis

- Testicular atrophy

Complications associated with scrotal exploration and testicular salvage include the following:

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Loss of testis

Nearly all of the aforementioned complications are irreversible. However, Yoshimura et al 15 reported restoration of spermatogenesis in a patient by orchiopexy 13 years after bilateral traumatic testicular dislocation. Although the patient was azoospermic before surgery and was found to have atrophic testicles rotated 180° intraoperatively, he was able to father a child 10 months later.

Animal-based research has found that grade I unilateral blunt testicular trauma, defined as intratesticular hemorrhage with an intact tunica albuginea, significantly affects germ cell maturation bilaterally and alters the sex hormone profile. Ischemia-reperfusion of the testis, which is possible in a trauma patient, has been shown to cause germ cell–specific apoptosis and subsequent aspermatogenesis. Lysiak et al 16 suggested that this may be due to a cytokine–stress-related kinase pathway.

Progressive testicular atrophy may occur in spite of a successful repair. Testicular atrophy is most likely the result of the original testicular trauma rather than efforts to salvage the testis. Cross and colleagues 17 performed a follow-up ultrasonographic study of unilateral testicular trauma patients. Half of the patients in that study were found to have atrophy of the injured side, defined as a reduction in volume of more than 50%, as compared with the unaffected side.

Testicular trauma-related torsion may account for 5%-6% of testicular torsion cases.

Testicular trauma diagnosis

Your urologist can often figure out how bad the injury to the testicle is with a physical exam. After asking questions about how the injury occurred, as well as other questions about your health, he/she will look at your scrotum. It’s often easy for your urologist to feel the tough testicle cover, as well as the thin, soft epididymis. He/she will also feel the structures that run into the testicle–the artery, vein and vas deferens–to make sure they’re normal.

If all seem normal with no injury, your urologist will likely give you pain meds, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen. You’ll also be told to wear a jock strap to support the scrotum.

Your urologists may obtain a urinalysis to rule out urinary tract infection or epididymo-orchitis.

If it’s not clear if injury has occurred, your urologist may ask for a scrotal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound uses sound waves bouncing off organs to make a picture of what’s inside your body. Based on the same sonar sound waves that guide submarines, this device can safely image parts of the sac, including the testicle, epididymis and spermatic cord, to check the blood flow.

Though no imaging test is 100% perfect, ultrasound is easy to do, uses no X-rays, and clearly shows the structure of the scrotum. In rare cases, the ultrasound leaves more questions than answers. Your urologists may ask for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a more sophisticated imaging technique.

Imaging studies

Scrotal ultrasonography with Doppler studies (performed by an experienced ultrasonographer or radiologist) is valuable for diagnosing and staging testicular injuries. A normal parenchymal echo pattern, with normal blood flow in cases of blunt trauma, can safely exclude significant injury. Acute bleeding or contusion of the testicular parenchyma typically appears as a hyperechoic area, whereas old blood appears as a hypoechoic lesion.

Acute and chronic hematoceles are observed as mixed hypoechoic and hyperechoic areas confined by the tunica vaginalis. The most specific finding for testicular rupture is a discrete fracture plane, but this is seen in only 17% of cases. Characterization seems to be further improved by the use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound, which may allow for more informed surgical decision-making 18.

Perform Doppler studies during the scrotal ultrasonography. Doppler studies provide information on the vascular status of the testes. Blood flow to the testis indicates that the vascular pedicle is intact. Absence of flow implies that a torsion or devascularizing injury has occurred to the spermatic cord.

Other imaging studies, such as nuclear imaging or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have been used to obtain additional information in equivocal cases. An animal-based study by Srinivas et al 19 demonstrated that MRI after blunt testicular trauma could assist in stratifying the extent of injury and provide information regarding prognosis.

Testicular trauma treatment

Surgical therapy is unnecessary in cases of minor trauma in which the testes are unequivocally spared and the scrotum has not been violated.

The usual conservative treatment for patients with minor trauma consists of the following:

- Scrotal support

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Ice packs

- Bed rest for 24-48 hours

Scrotal support decreases scrotal mobility and the likelihood of aggravating the injury. Anti-inflammatory medications decrease scrotal edema and provide nonsedating analgesia. Ice packs applied to the groin at least every 3-4 hours decrease swelling in the acute phase.

If associated epididymitis is suggested or if urinary tract infection is present, administer appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Failure of medical management after an appropriate period of observation warrants imaging of the scrotum with ultrasonography and Doppler studies.

In the case of testicular dislocation, manual reduction has been used successfully in 15% of cases. Future elective orchiopexy should still be performed to minimize the risk of torsion.

Attempts have been made to apply injury severity scales, such as that of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, to determine whether nonoperative management is appropriate in certain cases of testicular trauma. However, prospective validation and long-term outcome data are lacking.

Surgical therapy

If any imaging study suggests testicular injury, the usual course of action is surgery. Penetrating testicular trauma (with the possible exception of a superficial skin injury) should be explored in the operating room. Patients with a history of blunt trauma and associated hematoceles often undergo surgical exploration for earlier resolution of pain and shorter convalescence. However, some institutions defer surgical exploration of small (<5 cm) nonexpanding hematoceles following blunt trauma.

Begin broad-spectrum antibiotics preoperatively and continue postoperatively; gangrenous infection is the most feared complication of scrotal trauma.

Documented testicular injuries mandate immediate repair. Inappropriately protracted expectant management promotes testicular infection, atrophy, and necrosis. Delay in repair may herald the loss of spermatogenesis and hormonal functions. Lee et al reported that 20% of patients with a conservatively managed testicular rupture had atrophic changes on follow-up ultrasonography and consequently underwent delayed orchiectomy 20.

Proper operative management includes adequate debridement of necrotic or devitalized tissue, copious irrigation, meticulous attention to hemostasis, and closure of the tunica albuginea. This is true even if 50% of the parenchyma is destroyed.

Conservative debridement is critical to tissue preservation 21. In bilateral testicular injury with significant reduction in viable tunica albuginea, Yap et al reported successful salvage via merging of the remaining tissue into a single midline testis 22. A small, dependently placed drain and broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage are also indicated.

Injury to the vas deferens or epididymis may be repaired using microsurgical techniques. This is usually performed as a staged procedure several months later to avoid operating in a potentially contaminated field.

Sometimes an injury is so bad the testicle can’t be fixed. In this case, your urologist will remove the testicle (orchiectomy). Orchiectomy is rarely indicated, unless the testis is completely infarcted or shattered. This doesn’t mean you can’t father a child, though. Only 1 working testicle is needed for normal fertility. A single testicle will most often make normal amounts of sperm and testosterone. If your other testicle is normal, you should be able to get your partner pregnant.

Testicular injuries may be associated with significant loss of scrotal covering. Loss of scrotal skin from degloving injuries is most commonly the result of industrial or large machinery accidents and may be treated in 1 of 3 ways, as follows:

- The preferred method is primary closure of the testis using the remaining scrotal skin. A minimum of 20% of the original scrotal skin provides adequate coverage of the scrotal contents. Adequate debridement and copious irrigation are required before attempting primary closure.

- If the amount of remaining scrotal skin is insufficient, mobilize the testis to adjacent areas to obtain coverage. The optimal locations are subcutaneous thigh pouches, with delayed scrotal reconstruction in 4-6 weeks. The temperature of the thigh is approximately 10° lower than core body temperature, favoring spermatogenesis. Ramdas et al 23 reported a novel technique of temporary grafting of an avulsed testis to the forearm with successful staged microsurgical transfer to an orthotopic position at a more appropriate time.

- As a last resort, allow the testicles to remain exposed and apply daily moist-to-dry normal saline dressings until adequate granulation tissue forms. Within 1 week, follow this with a split-thickness skin graft, preferably harvested from the inner thigh.

Bilateral or unilateral testicular amputation treated within 8 hours with microvascular reimplantation techniques may allow successful revascularization. Thus, early involvement of appropriate specialists should be considered, even in the polytrauma patient 24. Sperm extraction for cryopreservation should be considered at this time. Do not place a testicular prosthesis until complete healing has occurred. If reimplantation is not possible, the ductus deferens should be cleaned and ligated, with subsequent primary closure. It is important to note that in the case of psychotic and transsexual men, 20-25% reattempt autoemasculation following reconstruction after genital self-mutilation.

Postoperative details

Continue intravenous antibiotics until patient discharge. Drainage usually becomes minimal within the first 24 hours, and the Penrose drain may be removed the day after surgery. If the drainage is persistent, discharge the patient home with the drain in place.

If associated perineal or penile injury has been sustained, leaving an indwelling catheter is advisable to prevent soilage of the operative site by urine. Discharge medications should include oral antibiotics and analgesics. Recommend scrotal support, ice packs to the groin area, and bed rest.

Follow-up

Instruct the patient to return for a follow-up visit in 1 week. If drain removal is necessary, instruct the patient to return for a follow-up visit in 24 hours.

Inspect the scrotal area for incision integrity and the presence of infection. Expect the scrotum to be somewhat enlarged and edematous from postsurgical edema and hematoma. This swelling and ecchymosis gradually subside over the next 4 weeks.

The final office visit usually occurs in 1 month. All athletes should be educated on the need for appropriate protective equipment.

Testicular trauma prognosis

Traumatic testicular injuries are relatively uncommon. When present, they are most often caused by blunt trauma. History, physical examination, and scrotal ultrasonography with Doppler studies are important in diagnosing and staging these injuries.

Surgical exploration of all testicular penetrating injuries and many blunt injuries has proven to increase testicular salvage rates and decrease morbidity. Early surgical intervention leads to higher salvage rates, shorter hospitalizations, and a more rapid return to baseline activity. Phonsombat et al 21 found that testicular salvage rates are significantly higher with gunshot wound injuries than with stab wounds and lacerations, as gunshot wounds less commonly involve the spermatic cord.

Following repair of penetrating testicular trauma caused by conventional bullet wounds, fertility results are approximately 62%. If the wound sustained was the product of high-velocity ammunition, fertility rates are much lower.

References- Testicular trauma. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/441362-overview

- Okonkwo KC, Wong KG, Cho CT, Gilmer L. Testicular trauma resulting in shock and systemic inflammatory response syndrome: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1(1):4. Published 2008 May 12. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-1-4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2438311

- Knight PJ, Vassy LE. The diagnosis and treatment of the acute scrotum in children and adolescents. Ann Surg. 1984;200:664–673. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198411000-00019

- Chandra RV, Dowling RJ, Ulubasoglu M, Haxhimolla H, Costello AJ. Rational approach to diagnosis and management of blunt scrotal trauma. Urology. 2007 Aug. 70(2):230-4.

- Buckley JC, McAninch JW. Use of ultrasonography for the diagnosis of testicular injuries in blunt scrotal trauma. J Urol. 2006 Jan. 175(1):175-8.

- Cubillos J, Reda EF, Gitlin J, Zelkovic P, Palmer LS. A conservative approach to testicular rupture in adolescent boys. J Urol. 2010 Oct. 184(4 Suppl):1733-8.

- Wan J, Corvino TF, Greenfield SP, DiScala C. Kidney and testicle injuries in team and individual sports: data from the national pediatric trauma registry. J Urol. 2003 Oct. 170(4 Pt 2):1528-3; discussion 1531-2.

- Bjurlin MA, Kim DY, Zhao LC, Palmer CJ, Cohn MR, Vidal PP, et al. Clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes of penetrating external genital injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Mar. 74 (3):839-44.

- Freehill MT, Gorbachinsky I, Lavender JD, Davis RL 3rd, Mannava S. Presumed testicular rupture during a college baseball game: a case report and review of the literature for on-field recognition and management. Sports Health. 2015 Mar. 7 (2):177-80.

- Joudi FN, Lux MM, Sandlow JI. Testicular rupture secondary to paint ball injury. J Urol. 2004 Feb. 171(2 Pt 1):797.

- Frauscher F, Klauser A, Stenzl A, Helweg G, Amort B, zur Nedden D. US findings in the scrotum of extreme mountain bikers. Radiology. 2001 May. 219(2):427-31.

- Jecmenica DS, Alempijevic DM, Pavlekic S, Aleksandric BV. Traumatic testicular displacement in motorcycle drivers. J Forensic Sci. 2011 Mar. 56(2):541-3.

- Ko SF, Ng SH, Wan YL, et al. Testicular dislocation: an uncommon and easily overlooked complication of blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2004 Mar. 43(3):371-5.

- Cline KJ, Mata JA, Venable DD, Eastham JA. Penetrating trauma to the male external genitalia. J Trauma. 1998 Mar. 44(3):492-4.

- Yoshimura K, Okubo K, Ichioka K, Terada N, Matsuta Y, Arai Y. Restoration of spermatogenesis by orchiopexy 13 years after bilateral traumatic testicular dislocation. J Urol. 2002 Feb. 167(2 Pt 1):649-50.

- Lysiak JJ, Nguyen QA, Kirby JL, Turner TT. Ischemia-reperfusion of the murine testis stimulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and activation of c-jun N-terminal kinase in a pathway to E-selectin expression. Biol Reprod. 2003 Jul. 69(1):202-10.

- Cross JJ, Berman LH, Elliott PG, Irving S. Scrotal trauma: a cause of testicular atrophy. Clin Radiol. 1999 May. 54(5):317-20.

- Valentino M, Bertolotto M, Derchi L, Bertaccini A, Pavlica P, Martorana G, et al. Role of contrast enhanced ultrasound in acute scrotal diseases. Eur Radiol. 2011 Jun 2.

- Srinivas M, Degaonkar M, Chandrasekharam VV, Gupta DK, Hemal AK, Shariff A. Potential of MRI and 31P MRS in the evaluation of experimental testicular trauma. Urology. 2002 Jun. 59(6):969-72.

- Lee SH, Bak CW, Choi MH, Lee HS, Lee MS, Yoon SJ. Trauma to male genital organs: a 10-year review of 156 patients, including 118 treated by surgery. BJU Int. 2008 Jan. 101(2):211-5.

- Phonsombat S, Master VA, McAninch JW. Penetrating external genital trauma: a 30-year single institution experience. J Urol. 2008 Jul. 180(1):192-5; discussion 195-6.

- Yap SA, DeLair SM, Ellison LM. Novel technique for testicular salvage after combat-related genitourinary injury. Urology. 2006 Oct. 68(4):890.e11-2.

- Ramdas S, Thomas A, Arun Kumar S. Temporary ectopic testicular replantation, refabrication and orthotopic transfer. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007. 60(7):700-3.

- A Ward M, L Burgess P, H Williams D, E Herrforth C, L Bentz M, D Faucher L. Threatened fertility and gonadal function after a polytraumatic, life-threatening injury. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010 Apr. 3(2):199-203.