Thoracic disc herniation

Thoracic discs are very stable and thoracic disc herniation is quite rare comprising 0.15% of all disc herniation and a peak incidence is in the fourth decade of life 1. Herniation of the uppermost thoracic discs can mimic cervical disc herniations, while herniation of the other discs can mimic lumbar herniations 2. Arce and Dhormann 3 reported that 75% of cases occurred below T8, whereas 3% of cases occurred between T1 and T2, and less than 1% occurred between T2 and T3. Disk degeneration is the main causing factor 4. Trauma is also considered to be a major factor. Up to 25% of patients have been found to report a history of trauma.

Asymptomatic thoracic disc herniations are relatively common in the general population. Autopsy studies have shown that the prevalence rate ranges from 7-15%. The prevalence of asymptomatic disc herniations found radiographically varies with the imaging modality used. Awwad et al 5 showed that 11-13% of asymptomatic subjects were found to have thoracic disc herniation on compute tomography (CT) myelograms, whereas Wood et al 6 showed 37% of such individuals were found to have thoracic disc herniation on magnetic resonance images (MRIs).

Despite the relatively high frequency of asymptomatic disc herniations, symptomatic disc herniations occur in a range from 1 in 1000 to 1 in 1 million persons. The number of patients with objective neurologic findings due to thoracic disc herniation is thought to be closer to 1 in 1 million annually.

Thoracic disc herniation has various and confusing manifestations. Among them, radicular pain down the leg could be the rarest presentation, especially if it is the only complaint. On the other hand, finding the relationship between clinical and paraclinical needs require high index of suspension and it is demanding because some patients have degenerated T12-L1 as a false positive paraclinical finding 7. A review of the related literature indicated that most cases of thoracic disk herniation were associated to mild-to-moderate clinical presentations involving sensorial complaints (abdominal wall pain) or pseudovisceral complaints of digestive, gynecologic, or urologic nature 4. Thus, the specialist to which such patients are often referred to, usually gastroenterologists, digestive surgeons, urologists, or gynecologists, hardly suspect the true cause of this clinical picture.

Pain is usually the first symptom. The pain may be centered over the injured disc but may spread to one or both sides of the mid-back. Also, patients commonly feel a band of pain that goes around the front of the chest. Patients may eventually report sensations of pins, needles, and numbness. Others say their leg or arm muscles feel weak. Disc material that presses against the spinal cord can also cause changes in bowel and bladder function.

Disc herniations can affect areas away from the spine. Herniations in the upper part of the thoracic spine can radiate pain and other sensations into one or both arms. If the herniation occurs in the middle of the thoracic spine, pain can radiate to the abdominal or chest area, mimicking heart problems. A lower thoracic disc herniation can cause pain in the groin or lower limbs and can mimic kidney pain.

Acute and subacute thoracic disc herniation occur in less than 10% of patients 8. Typically, thoracic disc herniation is the consequence of a soft herniation and is usually preceded by a minor trauma 7. A progressive course over a month or a year is predominant and calcification develops in more than 90% of patients 9.

The best way to diagnose a herniated thoracic disc is with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The MRI machine uses magnetic waves rather than X-rays to show the soft tissues of the body. It gives a clear picture of the discs and whether one has herniated. This machine creates pictures that look like slices of the area your doctor is interested in. The test does not require dye or a needle. This test has shown doctors that many people without symptoms have thoracic disc herniations. This has led some doctors to suggest that thoracic disc herniations not causing symptoms are normal.

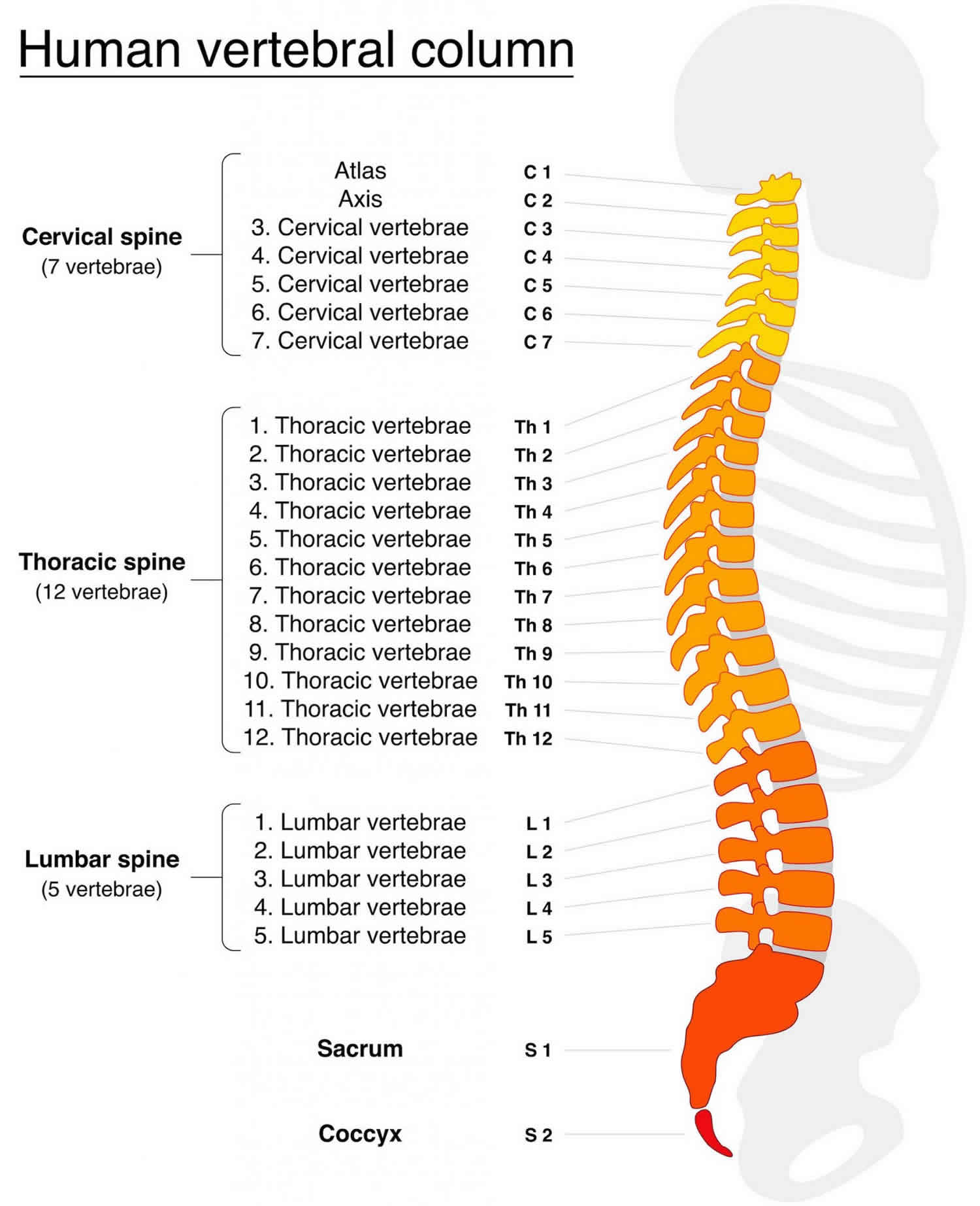

Thoracic spine anatomy

The thoracic region of the spine is relatively inflexible and functions primarily to provide erect posture and assist in weight bearing of the trunk, head, and upper extremities during daily activities. The vertebral bodies are taller posteriorly than anteriorly, resulting in an anterior concavity and normal thoracic kyphosis.

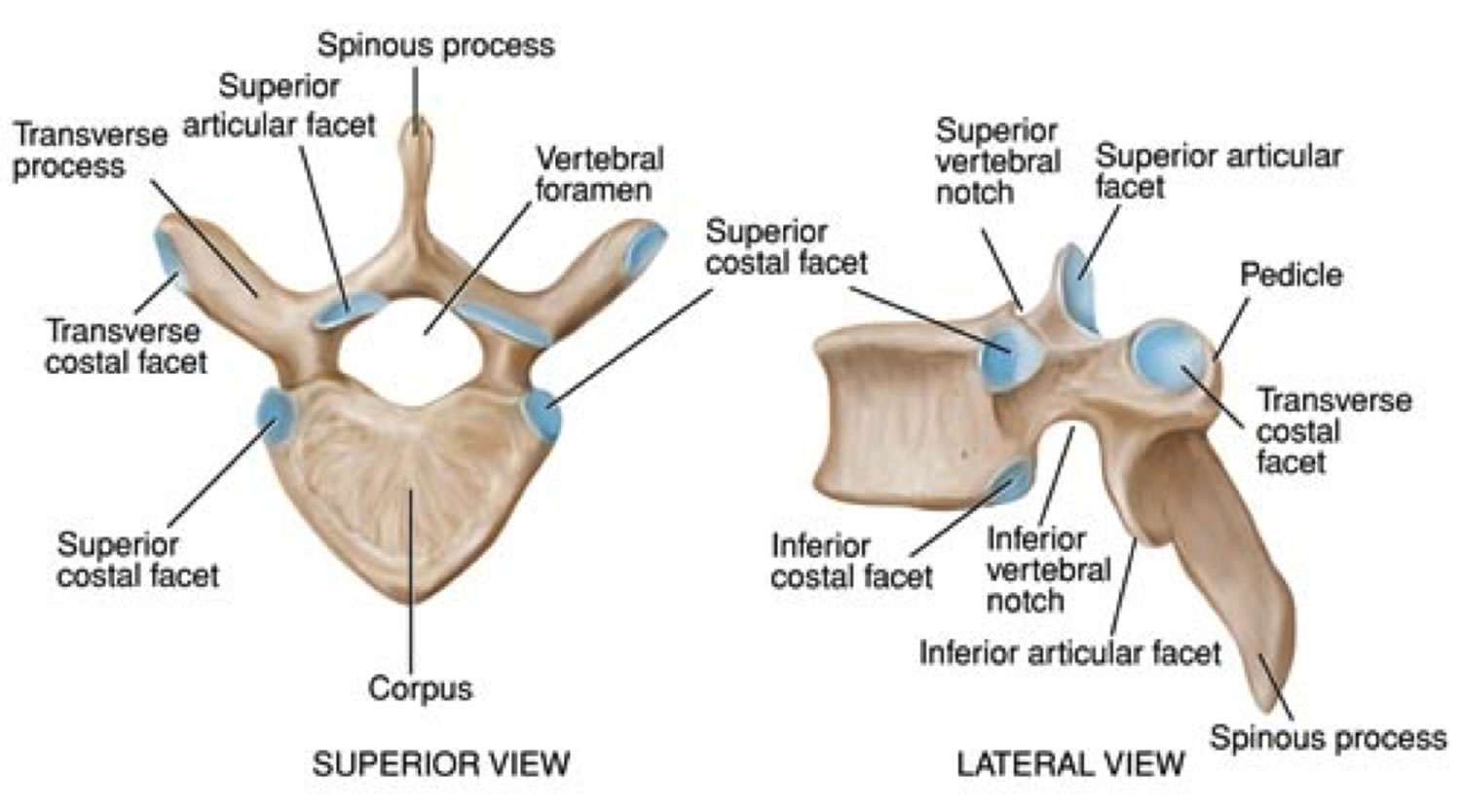

In the thoracic spine, the addition of the sternum, the ribs, and their associated ligamentous structures provide additional support and rigidity. The 10 most superior ribs articulate anteriorly with the sternum and posteriorly with the transverse processes and vertebral bodies. These ribs are oriented vertically, with slight medial angulation in the coronal plane. This arrangement provides the thoracic spine with relatively good stability in the midsagittal plane. However, it also affords less stability in the lateral and rotational planes. Biomechanical studies have shown that thoracic intervertebral discs are most susceptible to injury when torsional and lateral forces are applied in tandem.

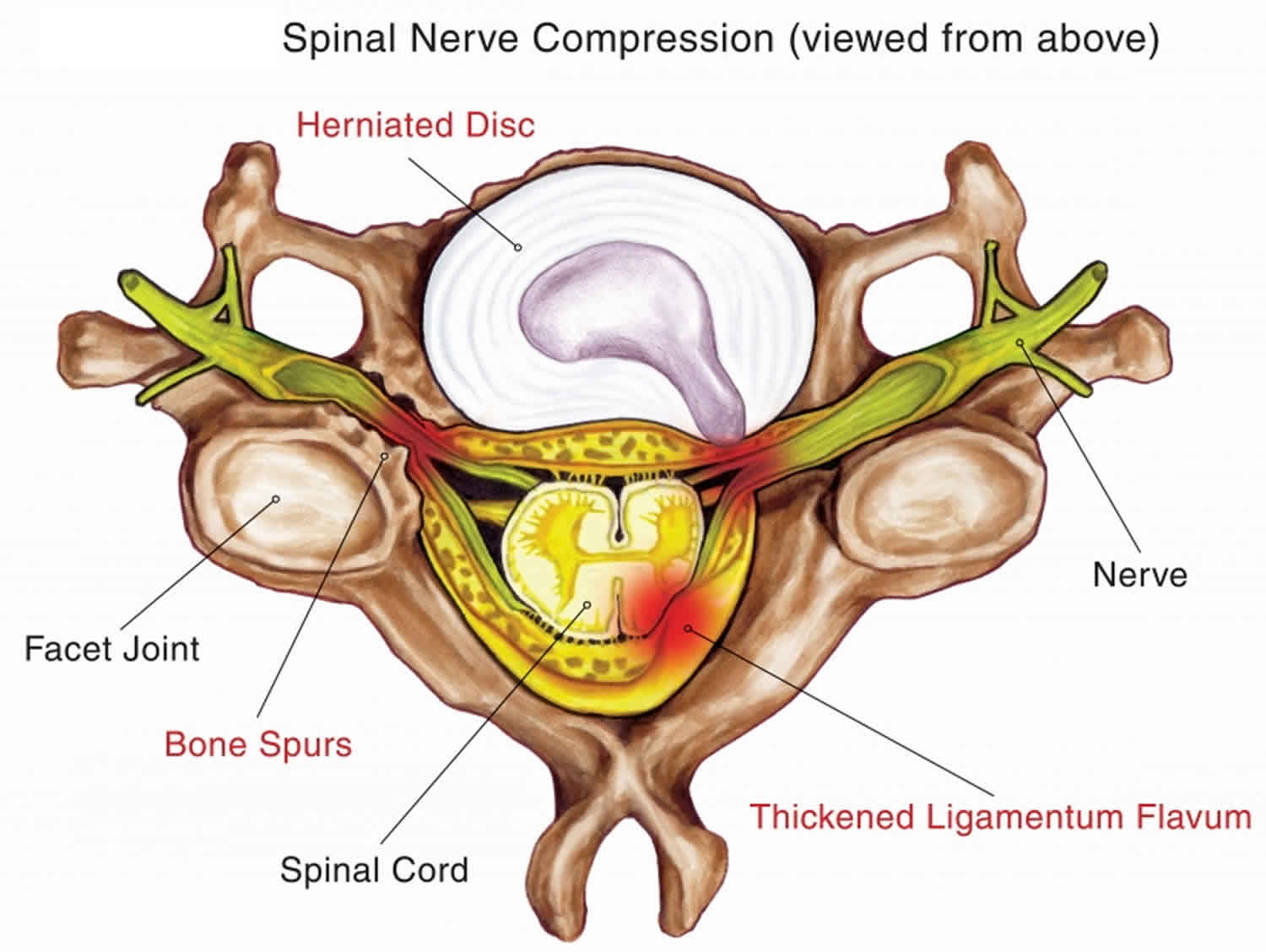

Several features of the thoracic spine increase its susceptibility to spinal cord compression associated with thoracic disc herniation, as follows:

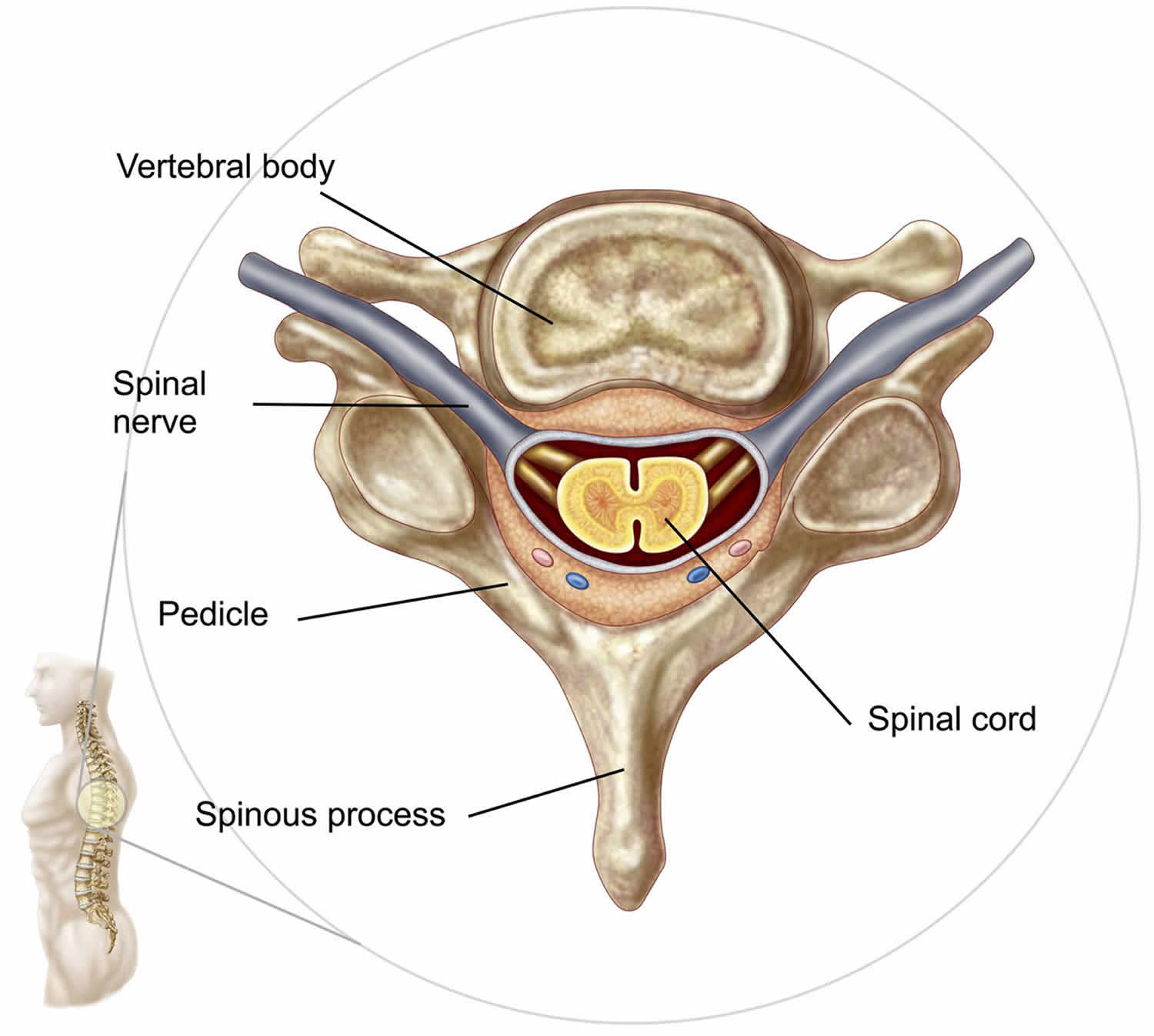

- The ratio of the spinal canal to the thoracic spinal cord is smaller than that found in the cervical and lumbar regions. Although the cross-sectional diameter of the thoracic cord is smaller than that of its cervical or lumbar counterparts, the diameter of the spinal canal is proportionally even smaller. Thus, the ratio of the spinal cord to the canal in the thoracic spine is 40%, whereas this ratio in the cervical spine is only 25%.

- The dentate ligaments situated between the spinal cord and the nerve roots restrict posterior movement of the spinal cord within the canal. This makes the thoracic spine prone to vertical compression from anterior disc and bony prominences.

- The natural kyphosis of the thoracic spine places the spinal cord in close proximity to the posterior longitudinal ligament and the posterior aspects of both the vertebral bodies and the discs in the thoracic region. This makes the thoracic cord especially susceptible to ventral compression from herniations.

Normal discs and disc degeneration

The 3 basic structures of normal vertebral discs are the nucleus pulposus, the annulus fibrosus, and the vertebral endplates. The nucleus pulposus is the gelatinous core of the disc and is composed mostly of water and proteoglycans. The annulus fibrosus surrounds the nucleus pulposus and is composed primarily of water and concentric layers of collagen. The vertebral endplates lie on the superior and inferior aspect of the discs adjacent to the vertebral bodies and aid in the diffusion of nutrients into the discs. As a normal part of aging, the water content of the discs decreases, leading to decreased disc height and impaired capability to absorb the axial loads of the spine. Disc herniations, annular tears, and endplate degeneration all can occur.

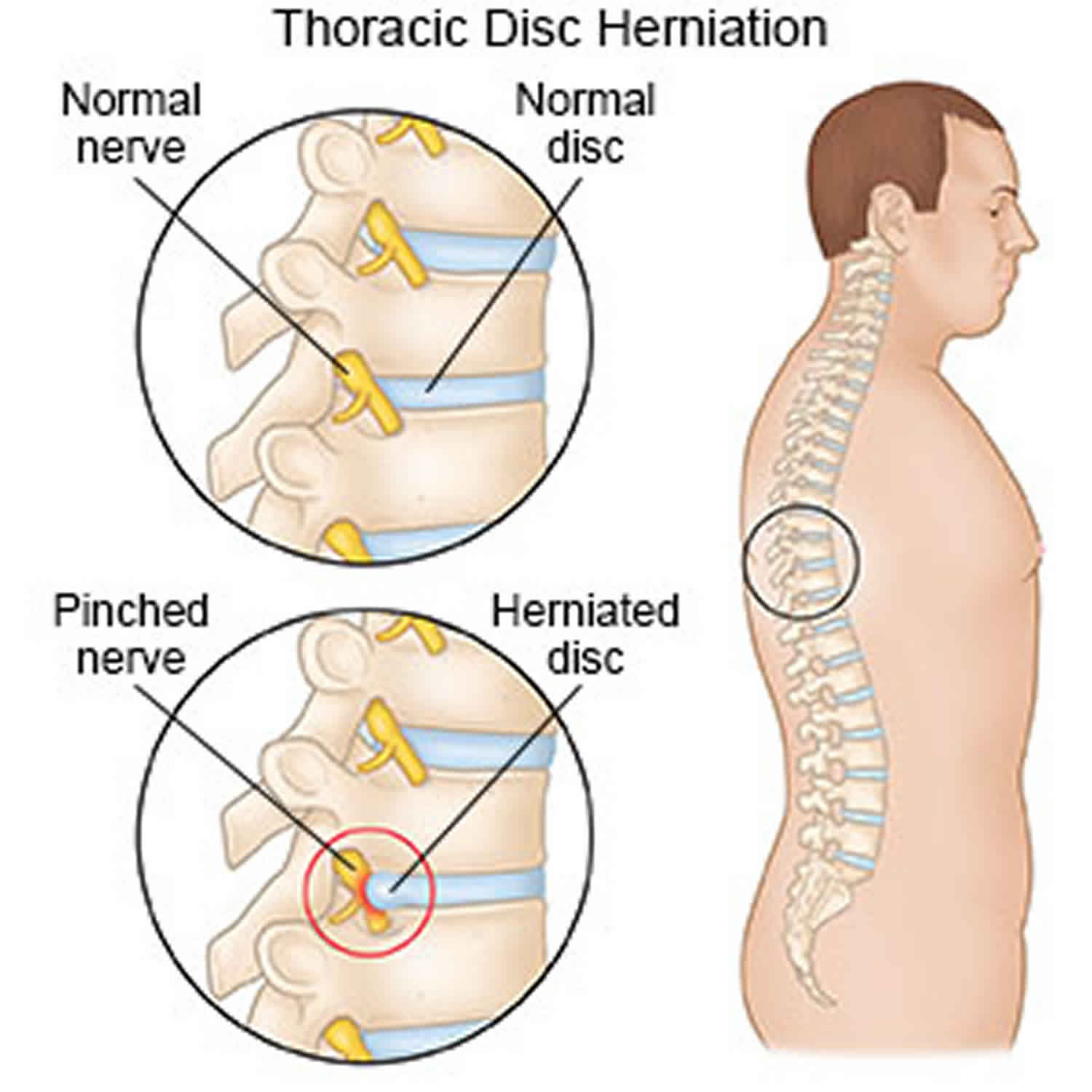

Figure 1. Thoracic spine anatomy

Figure 2. Thoracic vertebrae

Figure 3. Thoracic disc herniation

Thoracic herniated disc causes

Up to 90% of herniated discs in the thoracic spine are due to a wear and tear in the thoracic disc. This wear and tear is known as degeneration. As a normal part of aging, the water content of thoracic discs decreases, leading to decreased disc height and impaired capability to absorb the axial loads of the spine. Thoracic disc herniations, annular tears, and endplate degeneration all can occur. As a disc’s annulus ages, it tends to crack and tear. These injuries are repaired with scar tissue. Over time the annulus weakens, and the nucleus may squeeze (herniate) through the damaged annulus. Spine degeneration is common in T11 and T12. T12 is where the thoracic and lumbar spine meet. This link is subject to forces from daily activity, such as bending and twisting, which lead to degeneration. Not surprisingly, most thoracic disc herniations occur in this area.

Trauma can be an important factor in 10-20% of patients with thoracic disc herniation. In patients with symptomatic thoracic disc herniations for which trauma is implicated as the cause, a twisting or torsional movement is often involved. Participation in any sport that involves axial rotation of the spine can potentially increase the risk of disc herniation. These types of forces may be observed in sports such as golf, in which axial rotation of the spine is required at the top of the backswing, with subsequent uncoiling and hyperextension observed through the downswing and follow-through.

Diseases of the thoracic spine may lead to thoracic disc herniation. Patients with Scheuermann’s disease, for example, are more likely to suffer thoracic disc herniations. It appears these patients often have more than one herniated disc, though the evidence is not conclusive.

The spinal cord may be injured when a thoracic disc herniates. The spinal canal of the thoracic spine is narrow, so the spinal cord is immediately in danger from anything that takes up space inside the canal. Most disc herniations in the thoracic spine squeeze straight back, rather than deflecting off to either side. As a result, the disc material is often pushed directly toward the spinal cord. A herniated disc can cut off the blood supply to the spinal cord. Discs that herniate into the critical zone of the thoracic spine (T4 to T9) can shut off blood from the one and only blood vessel going to the front of the spinal cord in this section of the spine. This can cause the nerve tissues in the spinal cord to die, leading to severe problems of weakness or paralysis in the legs.

Location of thoracic disc herniation

Thoracic disc herniation are generally classified into 4 categories. These are central thoracic disc herniations, centrolateral thoracic disc herniations, lateral thoracic disc herniations, and intradural thoracic disc herniations. Central and centrolateral protrusions are the most common and are found in 70% of cases. Intradural herniations are rare and are found in less than 10% of cases. Clinical presentations vary, but the following generalizations are appropriate:

- Central protrusions may cause spinal cord compression, and patients may present with myelopathic symptoms, such as increased muscle tone, hyperreflexia, abnormal gait, and urinary/bowel incontinence.

- Centrolateral protrusions may result in a presentation resembling Brown-Sequard syndrome, with ipsilateral weakness and contralateral pain or sensory disturbances.

- Lateral herniations may cause nerve root compression, and patients may present with a radiculopathy.

Intraosseous disc herniations

Thoracic intervertebral discs can herniate into the spinal canal as well as through vertebral endplates, directly into the adjacent vertebral bodies. The resulting herniations are called Schmorl nodes or cartilaginous nodes. These can occur in association with osteoporosis, tumors, metabolic diseases, congenital weak points in the endplates, or degenerative endplate changes. Although Schmorl nodes often do not cause symptoms, an inflammatory, foreign body–type reaction can occur, resulting in severe pain.

Scheuermann disease, or juvenile kyphosis, is a disorder of childhood in which these types of changes are particularly pronounced. Children with this disorder generally present at age 8-16 years with rigid thoracic kyphoses. Although the exact etiology is not known, endplate degeneration and avascular necrosis of the ring apophysis result in the development of multilevel Schmorl nodes and vertebral wedging. This may cause the patient to have a severe kyphotic posture and pain in the early teenage years.

Annular tears

Tears in the annulus fibrosis may contribute to thoracic discogenic pain, even in the absence of an associated disc herniation. The outer third of the annulus fibrosis is innervated by the sinuvertebral nerve, which relays sensory information, including pain, to the dorsal root ganglion. Tears in this region, particularly radial tears, may be clinically significant. A study by Schellhas et al 10 evaluated the results of 100 patients with thoracic discographies. The study found that greater than 50% of painful discs had annular tears with no evidence of significant herniation.

Calcification

Calcification is also a common finding in thoracic disc herniations, particularly in those discs that are herniated as a result of degeneration. The terms “hard” disc herniations and “soft” disc herniations are used throughout the literature to indicate disc herniations with and without calcification, respectively. The presence and extent of calcification is also important in surgical planning.

Thoracic disc herniation prevention

Trauma and strain due to sport-related injuries or other causes is implicated in only 20% of patients with thoracic disc herniations. In many of these cases, a twisting or torsional movement is involved. Minimizing forces on the spine through the use of proper mechanics in specific sporting activities is important. Additionally, strengthening the dynamic stabilizers of the spine to counteract the significant forces exerted on the spine during certain athletic activities is also important.

Maintaining proper flexibility plays a significant role in the prevention of injury in athletes of all ages. Additionally, an improvement in aerobic fitness can increase blood flow and oxygenation to all tissues, including the muscles, bones, and ligaments of the spine. Aerobic conditioning is a reasonable addition to any rehabilitation and prevention program.

Thoracic herniated disc symptoms

Symptoms of thoracic disc herniation vary widely. Symptoms depend on where and how big the disc herniation is, where it is pressing, and whether the spinal cord has been damaged.

The diagnosis of thoracic discogenic pain syndrome can be challenging. The relative rarity of thoracic disc herniation makes it a diagnosis that is not often considered. Furthermore, the presentation of thoracic discogenic pain syndrome is variable and may resemble that of cervical or lumbar discogenic pain, which is much more common. When considering the diagnosis of thoracic discogenic pain syndrome, pertinent aspects of the patient history include the duration of symptoms, the extent of pain and weakness, and the presence of bowel or bladder symptoms.

Duration of symptoms

Thoracic discogenic pain syndrome most commonly manifests insidiously, with no history of a significant trauma. The initial symptom is usually pain, which then progresses to either radiculopathy or myelopathy to varying degrees. Nannapaneni and Marks 11 described a subset of patients that is young and often presents with a more definite history of trauma. These patients tend to have centrolateral disc herniations that either precipitate initial symptoms or intensify existing ones. These patients also tend to present with contralateral pain and sensory disturbances with ipsilateral weakness resembling Brown-Sequard syndrome.

Pain

Pain is the most common symptom in thoracic discogenic pain syndrome and is the presenting symptom in approximately 60% of affected patients. The quality and location of the pain depend on the location of the disc pathology and whether or not neural elements have been compromised. Purely discogenic pain may be dull and localized to the thoracic spine. Although less common, upper thoracic disc herniations may manifest as cervical pain and lower thoracic disc herniations may manifest as lumbar back pain. Pain may also be referred to the retrogastric, retrosternal, or inguinal areas, resulting in misdiagnoses such as cholecystitis, myocardial infarction, hernia, or nephrolithiasis.

According to Schellhas et al 10, annular tears may also have referral patterns based on the anatomic location of the tear. Anterior tears may refer pain to anterior extraspinal sites, such as the ribs, chest wall, sternum, or visceral structures. Lateral tears can produce radicular pain to either visceral or musculoskeletal sites. Posterior tears typically produce back pain, in either a local or diffuse pattern.

When a herniated disc compromises thoracic nerve roots, the patient may present with the symptoms listed above as well as radicular pain. This pain may be intermittent or constant and is usually described as electric, burning, or shooting in nature. The distribution is often bandlike, spanning the anterior chest wall. The T10 dermatomal region is most often described as the focus of pain, irrespective of the level involved. When cord compression and myelopathy are present, pain can be in any dermatome distal to the site of compression.

Sensory disturbances

Sensory disturbances may be the presenting symptom in approximately 25% of patients with thoracic discogenic pain syndrome. Numbness is the most commonly reported sensory disturbance, but dysesthesias and paresthesias in a dermatomal distribution may also be reported. The absence of these findings does not exclude thoracic discogenic pain syndrome, but, when present, they are highly suggestive of the diagnosis. A more concerning presentation of sensory disturbances is a wider distribution below the suspected thoracic disc herniation. This is consistent with myelopathy due to cord compression.

Cord compression can cause burning or tract dorsal pain (Lhermitte sign) below the lesion and gets worse by spine rotation due to irritation of ascending spinothalamic tract. Also, a dorsal vertebral pain is a vague and diffuse pain and resembles normal population back pain and fails to conform to any dermatomal distribution.

Weakness

Weakness may be the presenting symptom in 17% of patients with thoracic discogenic pain syndrome. The motor nerves of the thoracic spinal segments supply the abdominal and intercostal muscles. Although weakness of these muscles may occur, it is unlikely to be an early presenting symptom. Patients are more likely to present with weakness in the lower extremities when compression and myelopathy are present.

Bladder symptoms

Bladder symptoms (eg, incontinence) are the presenting symptom in only 2% of patients. However, bladder symptoms are common when cord compression and myelopathy have occurred. These patients may also have bowel incontinence.

Thoracic herniated disc diagnosis

Diagnosis begins with a complete history and physical examination. Your doctor will ask questions about your symptoms and how your problem is affecting your daily activities. These include questions about where you feel pain, if you have numbness or weakness in your arms or legs, and if you are having any problems with bowel or bladder function. Your doctor will also want to know what positions or activities make your symptoms worse or better.

Then the doctor examines you to see which back movements cause pain or other symptoms. Your skin sensation, muscle strength, and reflexes are also tested.

Imaging studies

Plain radiography

The primary role of radiographs in the evaluation of back pain is to evaluate for fracture, tumors, or infection. However, radiographs can also provide some useful information when evaluating for thoracic disc herniations. Osteophyte formation, disc-space narrowing, and kyphosis are signs of disc degeneration and often occur in conjunction with disc herniation. However, these findings have a low specificity for the diagnosis of thoracic disc herniation. Although not diagnostic, disc calcification is a more reliable finding when evaluating for thoracic disc herniation on radiographs. This finding is present in up to 70% of patients with thoracic disc herniation and is seen in only 4-6% of patients without thoracic disc herniation.

CT myelography

With the advent of MRI, CT myelography is used less frequently in the evaluation of thoracic discogenic pain syndrome. MRI has diagnostic advantages over CT myelography and does not involve injection of contrast into the epidural space. However, CT myelography is good for diagnosing lateral herniations and calcification, and this imaging modality is often used in preoperative planning.

MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most commonly used diagnostic test in the evaluation of thoracic disc herniation. It is the screening test of choice and is extremely sensitive for detecting disc abnormalities. Advantages of MRI compared with CT scanning or CT scanning with myelography include better visualization of the soft-tissue structures, earlier recognition of disc degeneration, and the ability to evaluate in the sagittal plane.

MRI can be used to determine the size and location of the disc herniation and to characterize it as a protrusion, extrusion, or sequestration. Although helpful in preoperative planning, these features may not be helpful in determining a prognosis. Brown et al 12 retrospectively reviewed the MRI results of 55 patients with symptomatic thoracic disc herniations. Fifteen patients ultimately needed surgery and 40 patients did well with conservative management. MRI could not help distinguish the discs in the surgically treated group from the discs in the conservatively treated group 12.

A more useful way of determining the severity of thoracic disc herniation with MRI may be quantifying the amount of neural compression. One such grading system suggested by Kaplan is as follows 13:

- Mild: The anterior epidural fat is not obliterated.

- Moderate: The epidural fat is obliterated, and the thecal sac is displaced.

- Severe: The cord is effaced or the nerve root(s) is displaced.

Despite the usefulness of MRI, it does have limitations. As technology has improved, thoracic disc herniations are more easily recognized. However, all of these thoracic disc herniations may not be clinically significant. Wood et al evaluated 90 individuals without thoracic pain to determine the frequency of abnormalities 14. Intervertebral degenerative changes, annular abnormalities, or both were found in 73% of the subjects; herniation was seen in 37% of the subjects.

MRI is also less sensitive for the evaluation of annular tears, particularly in the thoracic region. The high-intensity zone that commonly represents radial tears in cervical and lumbar MRIs is not seen as often in the thoracic region. These limitations underscore the importance of the patient’s history and physical examination. MRI plays an important role in the evaluation of thoracic discogenic pain syndrome, but the results must be interpreted in light of the clinical findings and with knowledge of the limitations of MRI.

Electrodiagnostic studies

Electrodiagnostic studies, including nerve conduction study, needle electromyography (EMG), and somatosensory evoked potentials, can be useful adjuncts to the history and physical examination. Nerve conduction study and EMG can be used in the evaluation of thoracic radiculopathy; however, their utility is limited by the limited number of tests, the lack of their ability to localize the level of involvement, and the risk of pneumothorax or penetration of the abdominal cavity with some techniques. However, nerve conduction study and EMG can be extremely useful in excluding other possible diagnoses, such as cervical radiculopathy, lumbosacral radiculopathy, and peripheral neuropathy.

Somatosensory evoked potentials should be considered in cases in which it is unclear whether clinical symptoms are due to an upper motor neuron or lower motor neuron process. Somatosensory evoked potentials can help make this distinction and can assist in directing subsequent treatment accordingly.

Discography

Thoracic discography may be considered in patients who are considering surgical intervention for predominantly axial back pain that is thought to be discogenic in nature 15. Discograms are most useful when they demonstrate single-level concordant pain that is associated with endplate irregularities or annular tears and normal discs at adjacent levels. However, the results of thoracic discography should be interpreted with caution.

Wood et al 14 showed that 55% of discograms performed in patients with symptomatic thoracic pain revealed concordant pain. Whether this large number of positive results represents multilevel disease or a high false-positive rate in the population is unclear. Furthermore, 2 of 10 asymptomatic patients demonstrated pain that could be interpreted as a positive result. Wood et al concluded that long-term prospective studies of surgical outcomes and their correlation with discography results are warranted.

Thoracic herniated disc treatment

Nonsurgical treatment

Doctors closely monitor patients with symptoms from a thoracic disc herniation, even when the size of the herniation is small. If the disc starts to put pressure on the spinal cord or on the blood vessels going to the spinal cord, severe neurological symptoms can develop rapidly. In these cases, surgery is needed right away. However, unless your condition is affecting the spinal cord or is rapidly getting worse, most doctors will begin with nonsurgical treatment.

At first, your doctor may recommend immobilizing your back. Keeping the back still for a short time can calm inflammation and pain. This might include one to two days of bed rest, since lying on your back can take pressure off sore discs and nerves. However, most doctors advise against strict bed rest and prefer their patients do ordinary activities, using pain to gauge how much activity is too much. Another option for immobilizing the back is a back support brace worn for up to one week.

Doctors prescribe certain types of medication for patients with thoracic disc herniation. Patients may be prescribed anti-inflammatory medications such as aspirin or ibuprofen. Muscle relaxants may be prescribed if the back muscles are in spasm. Pain that spreads into the arms or legs is sometimes relieved with oral steroids taken in tapering dosages.

Your doctor will probably have a physical therapist direct your rehabilitation program. Therapy treatments focus on relieving pain, improving back movement, and fostering healthy posture. A therapist can design a rehabilitation program for your condition that helps you prevent future problems.

Modalities such as electrical stimulation should be limited to the initial stages of treatment so that patients can progress quickly to more active treatment that addresses restoration of motion and strengthening.

Most people with a herniated thoracic disc get better without surgery. Doctors usually have their patients try nonoperative treatment for at least six weeks before considering surgery.

Epidural corticosteroid injections

For patients with a thoracic radiculopathy as a result of a thoracic disc herniation whose condition has not responded to conservative therapy, thoracic epidural steroid injections are a reasonable treatment option 16. The efficacy of epidural corticosteroid injections has been documented in cervical and lumbar radiculopathies. However, because of the small number of documented cases of thoracic discogenic pain syndrome, no study has been performed to evaluate efficacy for this specific condition.

Surgical treatment

Surgeons may recommend surgery if patients aren’t getting better with nonsurgical treatment, or if the problem is becoming more severe. When there are signs that the herniated disc is affecting the spinal cord, surgery may be required, sometimes right away. The signs surgeons watch for when reaching this decision include weakening in the arm or leg muscles, pain that won’t ease up, and problems with the bowels or bladder.

Surgical treatment for thoracic disc herniation includes:

- costotransversectomy and discectomy

- transthoracic decompression

- video assisted thoracoscopy surgery (VATS)

- fusion

Surgery for removal of a herniated thoracic disc is often a technically difficult procedure. The limited space available for spinal cord manipulation and the relatively tenuous blood supply increase the susceptibility of the spinal cord to injury during decompression. However, in the hands of a competent surgeon, carefully selected patients have had good outcomes 17.

No strict evidence-based indications have been developed for surgical thoracic discectomy; however, general guidelines have been determined. The general agreement is that surgery is indicated when myelopathic signs are present. These patients may benefit from early surgery because the rate of recovery diminishes when more advanced neurologic deficits are present. Surgical indications in cases of radiculopathy are less clear, because many patients’ conditions respond to conservative management. However, surgery is a viable option for patients with radicular symptoms who have not had a satisfactory response to conservative care. Patients with purely discogenic or axial pain are not generally treated surgically 18.

Many approaches can be used to remove herniated thoracic discs. The earliest surgical approach, used in the early 1900s, was a posterior laminectomy. That technique was used for many years until numerous studies demonstrated it produces poor results and has an unacceptable complication rate. In current practice, many other surgical options are available for thoracic disc herniations, all of which are modifications of 3 basic approaches.

The 3 approaches are the anterolateral, the lateral, and the posterolateral. The anterolateral approaches include transthoracic, trans-sternal, and thoracoscopic 19. The lateral approaches include costotransversectomy, lateral extracavitary, and parascapular. The posterolateral approaches are a transpedicular or transfacet pedicle-sparing procedure.

The decision regarding the most appropriate surgical approach is individualized and based on the consistency of the compressive disc, the level of herniation, its relationship to the spinal cord, and the likelihood of dural involvement 20. The surgeon’s familiarity with the particular approach must also be taken into consideration.

A study by Yoshihara et al 21 compared in-hospital morbidity and mortality rates between anterior and nonanterior approach procedures for thoracic disc herniation. The study concluded that anterior approach procedures for thoracic disc herniation were associated with increased in-hospital morbidity and mortality rates, as well as increased health care burden, compared with nonanterior approach procedures.

Costotransversectomy

Surgeons use costotransversectomy to open a window through the bones that cover the injured disc. Operating from the back of the spine, the surgeon takes out a small section on the end of two or more ribs where they connect to the spine. (Costo means rib.) Then the bony knob on the side of the vertebra (the transverse process) is removed. (Ectomy means to remove.) This opens a space for the surgeon to work. The injured portion of the disc that is pressing against the spinal cord is removed (discectomy) with small instruments. Surgeons take extreme care not to harm the spinal cord.

Transthoracic decompression

Transthoracic describes the approach used by the surgeon. Trans means across or through. The thoracic region is the chest. So in transthoracic decompression, the surgeon operates through the chest cavity to reach the injured disc. This approach gives the surgeon a clear view of the disc.

With the patient on his or her side, the surgeon cuts a small opening through the ribs on the side of the thorax (the chest). Instruments are placed through the opening, and the herniated part of the disc is taken out. This takes pressure off the spinal cord (decompression).

Video Assisted Thoracoscopy Surgery (VATS)

Recent developments in thoracic surgery include video assisted thoracoscopy surgery (VATS). This procedure is done with a thoracoscope, a tiny television camera that can be inserted into the side of the thorax through a small incision. The camera allows the surgeon to see the area where he or she is working on a TV screen. Small incisions give passage for other instruments used during the surgery. The surgeon watches the TV screen while cutting and removing damaged portions of the disc.

Categorized as minimally invasive surgery, VATS is thought to be less taxing on patients. Advocates also believe that this type of surgery is easier to perform, prevents scarring around the nerves and joints, and helps patients recover more quickly.

Fusion

After removing part or all of the disc, the spine may be loose and unstable. Fusion surgery may be needed immediately afterward. The medical term for fusion is arthrodesis. This procedure locks the vertebrae in place and stops movement between the vertebrae. This steadies the bones and can ease pain. Fusion surgery is not usually needed if only a small amount of bone and disc material was removed during surgery to fix a herniated thoracic disc.

In this procedure, the surgeon lays small grafts of bone over or between the loose spinal bones. Surgeons may use a combination of screws, cables, and rods to prevent the vertebrae from moving and allow the graft to heal.

After surgery

Rehabilitation after surgery is more complex. Some patients leave the hospital shortly after surgery. However, some surgeries require patients to stay in the hospital for a few days. Patients who stay in the hospital may be visited by a physical therapist soon after surgery. The treatment sessions help patients learn to move and do routine activities without putting extra strain on the back.

During recovery from surgery, patients should follow their surgeon’s instructions about wearing a back brace or support belt. They should be cautious about overdoing activities in the first few weeks after surgery.

Many surgical patients need physical therapy outside of the hospital. They see a therapist for one to three months, depending on the type of surgery. At first, therapists may use treatments such as heat or ice, electrical stimulation, massage, and ultrasound to calm pain and muscle spasm. Then they teach patients how to move safely with the least strain on the healing back.

As patients recover, they gradually begin doing flexibility exercises for the hips and shoulders. Mobility exercises are also started for the back. Strengthening exercises address the back muscles. Patients may work with the therapist in a pool. Patients progress with exercises to improve endurance, muscle strength, and body alignment.

As the rehabilitation program evolves, patients do more challenging exercises. The goal is to safely advance strength and function.

Ideally, patients are able to go back to their previous activities. However, some patients may need to modify their activities to avoid future problems.

When treatment is well under way, regular visits to the therapist’s office will end. The therapist will continue to be a resource. But patients are in charge of doing their exercises as part of an ongoing home program.

Rehabilitation

Even if you don’t need surgery, your doctor may recommend that you work with a physical therapist. Patients are normally seen a few times each week for four to six weeks. Physical therapy should emphasize extension-based strengthening exercises, postural training, and education in proper posture and body mechanics.

The first goals of treatment are to control symptoms, find positions that ease pain, and teach you how to keep your spine safe during routine activities. Pain during this phase should be judiciously managed with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, or other oral agents to allow the patient to adequately participate in therapy.

As patients recover, they gradually advance in a series of strengthening exercises. Aerobic exercises, such as walking or swimming, can ease pain and improve endurance.

With the progression of therapy and control of painful symptoms, a spine stabilization program should follow. With spine stabilization exercises, the goal is to teach the patient how to find and maintain a neutral spine during everyday activities. The neutral spine position is specific to the individual and is determined by the pelvic and spine posture that places the least stress on the elements of the spine and supporting structures. In classic discogenic pain, the neutral spine has an extension bias.

In classic posterior element pain and spinal stenosis, both of which may result from the ongoing degenerative cascade initiated by disc degeneration, the neutral spine may have a mild flexion bias. Dynamic spinal stabilization may be used with the McKenzie approach to provide dynamic muscular control and to protect the spine from biomechanical stresses, including tension, compression, torsion, and shear. Spinal stabilization emphasizes the synergistic activation of the trunk and spinal musculature in the midrange position.

Strengthening of the abdominal and gluteal muscle groups is emphasized, because these muscles attach to the thoracolumbar fascial support system, one of the potential spine stabilizing structures. The overall goals of this comprehensive exercise program are to reduce pain, to develop the muscular support of the trunk and spine, and, ultimately, to diminish the overall stress to the intervertebral disc and other static stabilizers of the spine.

Return to play

Return-to-play criteria following thoracic disc herniation or thoracic discogenic pain syndrome require the athlete to be free of signs or symptoms due to the original injury, to have full range of motion, to have normal strength and flexibility, and to have healthy sport-specific mechanics. Athletes must be aware of their own limitations, a concept that is particularly important for individuals gradually returning to a competitive level of activity after an injury.

Thoracic disk herniation prognosis

The progression of symptoms in patients with thoracic disc herniation varies considerably. When seen in younger patients, traumatic disc herniations may later cause myelopathy. In middle-aged persons, in whom degenerative disc herniation is more common, the course of symptoms involving spinal cord compression is often more protracted.

In patients who present with unilateral symptoms, the progression of symptoms is often slower than that of patients who have a bilateral presentation. In any case, a patient without evidence of myelopathy should receive conservative treatment. A return to previous activity level occurs in approximately 80% of patients treated with nonsurgical measures. Patients with intractable pain, progressive neurologic deficits, or bilateral involvement often require surgical intervention.

References- Surgical Treatment for Central Calcified Thoracic Disk Herniation: A Novel L-Shaped Osteotome. Zhuang QS, Lun DX, Xu ZW, Dai WH, Liu DY. Orthopedics. 2015 Sep; 38(9):e794-8.

- Thoracic Disc Injuries. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/96168-overview

- Thoracic disc herniation. Improved diagnosis with computed tomographic scanning and a review of the literature. Arce CA, Dohrmann GJ. Surg Neurol. 1985 Apr; 23(4):356-61.

- Lara FJ, Berges AF, Quesada JQ, Ramiro JA, Toledo RB, Muñoz HO. Thoracic disk herniation, a not infrequent cause of chronic abdominal pain. Int Surg. 2012;97(1):27–33. doi:10.9738/CC98.1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3723187

- Awwad EE, Martin DS, Smith KR Jr, Baker BK. Asymptomatic versus symptomatic herniated thoracic discs: their frequency and characteristics as detected by computed tomography after myelography. Neurosurgery. 1991 Feb. 28(2):180-6.

- Wood KB, Garvey TA, Gundry C, Heithoff KB. Magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic spine. Evaluation of asymptomatic individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995 Nov. 77(11):1631-8.

- Golbakhsh M, Mottaghi A, Zarei M. Lower thoracic disc herniation mimicking lower lumbar disk disease: A case report. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2017;31:87. Published 2017 Dec 16. doi:10.14196/mjiri.31.87 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6014753

- A novel approach to thoracic disk herniation. Ziewacz JE, Mummaneni P. World Neurosurg. 2013 Sep-Oct; 80(3-4):317-8.

- Minimally invasive approaches in the treatment of thoracic disk herniation. Bydon M, Gokaslan Z. World Neurosurg. 2014 May-Jun; 81(5-6):717-8.

- Schellhas KP, Pollei SR, Dorwart RH. Thoracic discography. A safe and reliable technique. Spine. 1994 Sep 15. 19(18):2103-9.

- Nannapaneni R, Marks SM. Posterolateral thoracic disc disease: clinical presentation and surgical experience with a modified approach. Br J Neurosurg. 2004 Oct. 18(5):467-70.

- Brown CW, Deffer PA Jr, Akmakjian J, Donaldson DH, Brugman JL. The natural history of thoracic disc herniation. Spine. 1992 Jun. 17(6 suppl):S97-102.

- Kaplan PA, Helms CA, Dussault R, Anderson MW, Major NM. Musculoskeletal MRI. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Company; 2001. 279-332.

- Wood KB, Schellhas KP, Garvey TA, Aeppli D. Thoracic discography in healthy individuals. A controlled prospective study of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals. Spine. 1999 Aug 1. 24(15):1548-55.

- Singh V, Manchikanti L, Onyewu O, Benyamin RM, Datta S, Geffert S, et al. An update of the appraisal of the accuracy of thoracic discography as a diagnostic test for chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2012 Nov-Dec. 15(6):E757-75.

- [Guideline] Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, Benyamin RM, Boswell MV, Buenaventura RM, et al. An update of comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in chronic spinal pain. Part II: guidance and recommendations. Pain Physician. 2013 Apr. 16(2 Suppl):S49-283.

- Court C, Mansour E, Bouthors C. Thoracic disc herniation: Surgical treatment. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018 Feb. 104 (1S):S31-S40.

- Boswell MV, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al, for the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians. Interventional techniques: evidence-based practice guidelines in the management of chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2007 Jan. 10(1):7-111.

- Quint U, Bordon G, Preissl I, Sanner C, Rosenthal D. Thoracoscopic treatment for single level symptomatic thoracic disc herniation: a prospective followed cohort study in a group of 167 consecutive cases. Eur Spine J. 2011 Dec 10.

- Kerezoudis P, Rajjoub KR, Goncalves S, Alvi MA, Elminawy M, Alamoudi A, et al. Anterior versus posterior approaches for thoracic disc herniation: Association with postoperative complications. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018 Apr. 167:17-23.

- Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D. Comparison of in-hospital morbidity and mortality rates between anterior and nonanterior approach procedures for thoracic disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014 May 20. 39 (12):E728-33.