Toxocariasis

Toxocariasis is the parasitic infection transmitted from animals to humans (zoonosis) caused by the larvae of two species of Toxocara roundworms (also known as nematode): Toxocara canis from dogs and, less commonly, Toxocara cati from cats. It is not known whether other closely-related Toxocara species can infect humans (e.g. Toxocara malaysiensis of cats). Anyone can become infected with Toxocara. Young children and owners of dogs or cats have a higher chance of becoming infected. Approximately 5% of the U.S. population has antibodies to Toxocara. This suggests that tens of millions of Americans may have been exposed to the Toxocara parasite.

In most cases, Toxocara infections are not serious, and many people, especially adults infected by a small number of larvae (immature worms), may not notice any symptoms. The most severe cases are rare, but are more likely to occur in young children, who often play in dirt, or eat dirt (pica) contaminated by dog or cat feces.

Toxocara species are prevalent worldwide, their concentration is in areas with large populations of domestic dogs and cats 1. Worldwide, Toxocara predominantly affects children in tropical and subtropical regions. Globally, toxocariasis is more common in developing countries, with seroprevalence reported above 80% in children in parts of Nigeria 2. In the United States, the seroprevalence estimates range from 5% to 15% and approximately 10,000 clinical cases are diagnosed yearly 3. Risk factors for Toxocara contraction include poverty, latitude, contaminated soil, young age, and high concentration of dogs and cats. There is a large discrepancy in prevalence between the developed and developing world just due to these risk factors.

Clinical disease is due to parasitic nematode larva migration through tissues. The signs and symptoms of toxocariasis reflect the number of migrating larvae, where the larvae have migrated in the body, and the degree of immune response and inflammation that developed in response to the presence of the larvae. Many infections are asymptomatic. In heavy infections, large numbers of larvae may migrate through liver and lungs or other internal organs, causing inflammation and symptomatic disease (visceral toxocariasis). Rarely, larvae may migrate to the central nervous system (CNS) causing eosinophilic meningoencephalitis or granuloma formation in the central nervous system. Signs of visceral toxocariasis include fever, cough, wheezing, abdominal pain, and hepatomegaly. Eosinophilia is often present. Visceral toxocariasis has been proposed as a cause of asthma; however, there may be multifactorial causes of asthma and further study is needed to establish a causative link between toxocariasis and asthma.

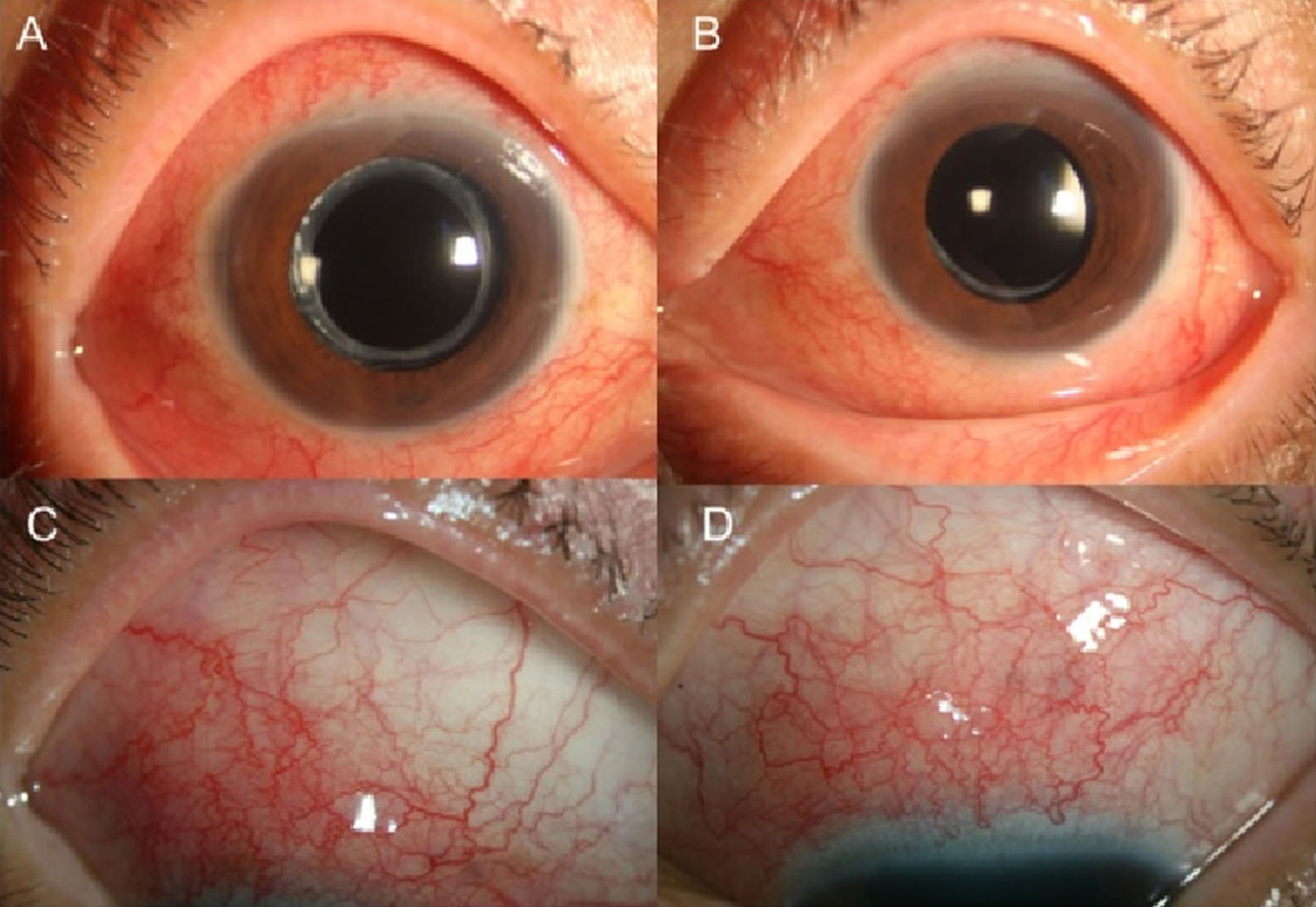

Typically, ocular toxocariasis is a unilateral disease, when a larva penetrates a single eye. Common signs are associated with granulomatous inflammation especially in the retina, uveitis, and/or chorioretinitis. Patients can present with leukocoria and decreased vision in the affected eye which may be confused with retinoblastoma. Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis or vitreal bands may develop.

Toxocariasis can be difficult to diagnose because the symptoms of toxocariasis are similar to the symptoms of other infections. A blood test is available that looks for evidence of infection with Toxocara larvae. In addition to the blood test, diagnosis of toxocariasis includes identifying the presence of typical clinical signs of visceral toxocariasis or ocular toxocariasis and a compatible exposure history.

Visceral toxocariasis is treated with antiparasitic drugs. Treatment of ocular toxocariasis is more difficult and usually consists of measures to prevent progressive damage to the eye. Visceral toxocariasis can be treated with antiparasitic drugs such as albendazole or mebendazole. Treatment of ocular toxocariasis is more difficult and usually consists of measures to prevent progressive damage to the eye.

Figure 1. Ocular toxocariasis

Footnote: Anterior segment of the right (a and c) and left eye (b and d). (a) and (b) show diffuse injections of both eyes. Episcleral and deep scleral vessels were engorged diffusely (c and d)

[Source 4 ]How is toxocariasis spread?

The most common Toxocara parasite of concern to humans is Toxocara canis, which puppies usually contract from their mother before birth or from her milk. The larvae mature rapidly in the puppy’s intestine; when the pup is 3 or 4 weeks old, the worms inside the puppy begin to produce large numbers of eggs that contaminate the environment through the puppy’s feces. After the eggs pass into the environment, it takes about 2 to 4 weeks for infective larvae to develop in the eggs. If a person ingests one of these infective eggs, then they can become infected with toxocariasis.

Toxocariasis is not spread by person-to-person contact like a cold or the flu.

What should I do if I think I have toxocariasis?

See your health care provider to discuss the possibility of infection and, if necessary, to be examined. Your provider may take a sample of your blood for testing.

Toxocara causes

Dogs and cats that are infected with Toxocara can shed Toxocara eggs in their feces. Adults and children can become infected by accidentally swallowing dirt that has been contaminated with dog or cat feces that contain infectious Toxocara eggs. Although it is rare, people can also become infected from eating undercooked meat containing Toxocara larvae.

Definite Toxocara hosts include cats, dogs, foxes, coyotes, and wolves 1. These hosts harbor the nematodes in their gut, shedding eggs in their feces. These embryonated eggs remain infectious for years outside the definitive host. In the wild, intermediate hosts such as other cats, dogs, rabbits, and fowl ingest the cysts, which hatch and migrate to various muscles and organs to encyst. In the wild, carnivorous animals such as cats and dogs consume infected meat (or simply soil containing the eggs), and the parasite remains in their gut. Additionally, there is solid documentation of transplacental transmission in dogs and cats. Humans are amongst a plethora of possible intermediate animal hosts. Clinical disease results from the migration of the parasite through extra-intestinal tissues 5.

Clinical Toxocariasis is a product of Toxocara species migration through tissues. Toxocara canis primarily infects canids (dogs, foxes, and wolves) whereas Toxocara cati primarily infects felids (cats). Toxocara cati is thought to more frequently cause severe human disease. Children are more prone to infection via the fecal-oral route as they are more likely to consume Toxocara eggs by ingesting soil or other contaminated substances. Epidemiologic studies have found that public parks with community sandboxes have particularly high egg burdens, placing children frequenting these areas at risk 6.

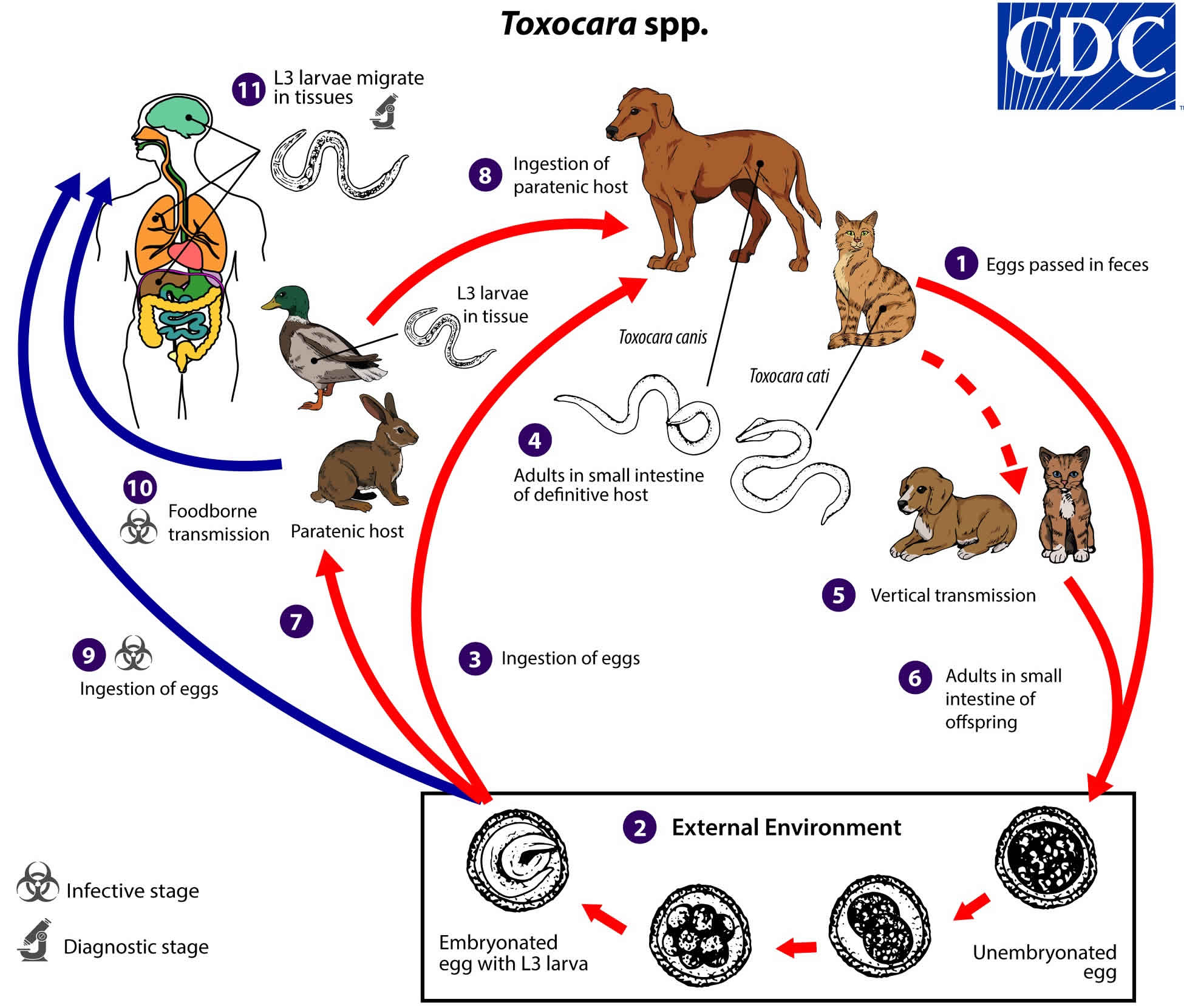

Toxocara life cycle

Toxocara species can follow a direct (one host) or indirect (multiple host) life cycle. Unembryonated eggs are shed in the feces of the definitive host (canids: Toxocara canis; felids: Toxocara cati) (number #1). Eggs embryonate over a period of 1 to 4 weeks in the environment and become infective, containing third-stage (L3) larvae (number #2). Following ingestion by a definitive host (number #3), the infective eggs hatch and larvae penetrate the gut wall. In younger dogs (Toxocara canis) and in cats (Toxocara cati), the larvae migrate through the lungs, bronchial tree, and esophagus, where they are coughed up swallowed into the gastrointestinal tract; adult worms develop and oviposit in the small intestine (number #4). In older dogs, patent (egg-producing) infections can also occur, but larvae more commonly become arrested in tissues. Arrested larvae are reactivated in female dogs during late gestation and may infect pups by the transplacental (major) and transmammary (minor) routes (number #5) in whose small intestine adult worms become established (number #6). In cats, Toxocara cati larvae can be transmitted via the transmammary route (number #5) to kittens if the dam is infected during gestation, but somatic larval arrest and reactivation does not appear to be important as in Toxocara canis.

Toxocara spp. can also be transmitted indirectly through ingestion of paratenic hosts. Eggs ingested by suitable paratenic hosts hatch and larvae penetrate the gut wall and migrate into various tissues where they encyst (number #7). The life cycle is completed when definitive hosts consume larvae within paratenic host tissue (number #8), and the larvae develop into adult worms in the small intestine.

Humans are accidental hosts who become infected by ingesting infective eggs (number #9) or undercooked meat/viscera of infected paratenic hosts (number #10). After ingestion, the eggs hatch and larvae penetrate the intestinal wall and are carried by the circulation to a variety of tissues (liver, heart, lungs, brain, muscle, eyes) (number #11). While the larvae do not undergo any further development in these sites, they can cause local reactions and mechanical damage that causes clinical toxocariasis.

Figure 2. Toxocara life cycle

Risk factor for toxocariasis

Infected dogs and cats shed Toxocara eggs in their feces into the environment. Once in the environment, it takes 2 to 4 weeks for Toxocara larvae to develop inside the eggs and become infectious. Toxocara eggs have a strong protective layer, which allows the eggs to survive in the environment for months or even years under the right conditions. Humans or other animals (e.g. rabbits, pigs, cattle, or chickens) can be infected by accidentally ingesting Toxocara eggs. For example, humans can become infected if they work with dirt and accidentally ingest dirt containing Toxocara eggs. Although rare, people can be infected by eating undercooked or raw meat from an infected animal such as a lamb or rabbit. Because dogs and cats are frequently found where people live, there may be large numbers of infected eggs in the environment. Once in the body, the Toxocara eggs hatch and the larvae can travel in the bloodstream to different parts of the body, including the liver, heart, lungs, brain, muscles, or eyes. Most infected people do not have any symptoms. However, in some people, the Toxocara larvae can cause damage to these tissues and organs. The symptoms of toxocariasis, the disease caused by these migrating larvae, include fever, coughing, inflammation of the liver, or eye problems.

A U.S. study in 1996 showed that 30% of dogs younger than 6 months deposit Toxocara eggs in their feces; other studies have shown that almost all puppies are born already infected with Toxocara canis. Research also suggests that 25% of all cats are infected with Toxocara cati. Infection rates are higher for dogs and cats that are left outside and allowed to eat other animals. In humans, it has been found that 5% of the U.S. population has been infected with Toxocara. Globally, toxocariasis is found in many countries, and prevalence rates can reach as high as 40% or more in parts of the world. There are several factors that have been associated with higher rates of infection with Toxocara. People are more likely to be infected with Toxocara if they own a dog. Children and adolescents under the age of 20 are more likely to test positive for Toxocara infection than adults. This may be because children are more likely to eat dirt and play in outdoor environments, such as sandboxes, where dog and cat feces can be found. This infection is more common in people living in poverty. Geographic location plays a role as well, because Toxocara is more prevalent in hot, humid regions where eggs are able to survive better in the soil.

Toxocariasis prevention

Controlling Toxocara infection in dogs and cats will reduce the number of infectious eggs in the environment and reduce the risk of infection for people. Have your veterinarian treat your dogs and cats, especially young animals, regularly for worms. This is especially important if your pets spend time outdoors and may become infected again.

There are several things that you can do around your home to make you and your pets safer, including the following:

- Clean your pet’s living area at least once a week; every day is better. Feces should be either buried or bagged and disposed of in the trash. Wash your hands after handling pet waste.

- Do not allow children to play in areas that are soiled with pet or other animal feces and cover sandboxes when not in use to make sure that animals do not get inside and contaminate them.

- Wash your hands with soap and warm water after playing with your pets or other animals, after outdoor activities, and before handling food or eating.

- Teach children the importance of washing hands to prevent infection.

- Teach children that it is dangerous to eat dirt or soil.

Toxocara eggs have a strong protective layer, which allows the eggs to survive in the environment for months or even years under the right conditions. Many common disinfectants are not effective against Toxocara eggs but extreme heat has been shown to kill the eggs. Prompt removal of animal feces can help prevent infection since the eggs require 2 to 4 weeks to become infective once they are passed out of the animal.

Although rare, people can also be infected by eating undercooked or raw meat from an infected animal such as a lamb or rabbit. Meat and offal should always be cooked thoroughly and to appropriate temperatures to prevent illness.

Toxocariasis symptoms

Many people who are infected with Toxocara do not have symptoms and do not ever get sick. There are two major forms of toxocariasis, visceral toxocariasis also called visceral larva migrans and ocular toxocariasis also called ocular larva migrans. The syndromes visceral larva migrans and ocular larva migrans can be caused by infection with the migrating larvae of other kinds of parasites which cause symptoms similar to those caused by migrating Toxocara larvae.

Some people may get sick from the infection and may develop the following:

- Ocular toxocariasis: Ocular larva migrans occurs when Toxocara larvae migrate through the posterior segment of the eye. Symptoms and signs of ocular toxocariasis include vision loss, eye inflammation or damage to the retina. Typically, only one eye is affected. Ocular toxocariasis is a leading infectious cause of blindness in children in developed countries. Ocular toxocariasis classically presents with unilateral vision loss in a child, most often between the ages of five to ten. The exam may demonstrate uveitis, retinitis, choroiditis, or endophthalmitis based on the location of the parasite. The infection can also result in secondary glaucoma. Histologically, eosinophilic abscesses with surrounding granulomatous reactions are the expected manifestations.

- Visceral toxocariasis: Visceral toxocariasis occurs when Toxocara larvae migrate to various body organs, such as the liver or central nervous system. Symptoms of visceral toxocariasis include fever, fatigue, coughing, wheezing, or abdominal pain. Visceral toxocariasis should be considered in any child presenting with fever, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and eosinophilia. An exam may be notable for hepatosplenomegaly, which can serve as a clue for clinicians that the presentation is not simple viral gastroenteritis. Lung involvement can result in bronchospasm and wheezing. Central nervous system disease is rare but can be severe and range from eosinophilic meningitis to fulminant meningoencephalitis, presenting with seizures, encephalopathy or neuropsychiatric symptoms 7.

- Covert toxocariasis is a mild, subclinical, febrile illness. Symptoms can include cough, difficulty sleeping, abdominal pain, headaches, and behavioral problems. Examination may reveal hepatomegaly, lymphadenitis, and/or wheezing.

In a few people who are infected with high numbers of Toxocara larvae or have repeated infections, the larvae can travel through parts of the body such as the liver, lungs, or central nervous system and cause symptoms such as fever, coughing, enlarged liver or pneumonia. This form of toxocariasis is called visceral toxocariasis. The larvae can also travel to the eye and cause ocular toxocariasis. Ocular toxocariasis occurs when a microscopic Toxocara larva enters the eye and causes inflammation and scarring on the retina. Ocular toxocariasis typically occurs only in one eye and can cause irreversible vision loss.

Toxocariasis complications

Decreased visual acuity or blindness may occur if ocular toxocariasis is not identified and treated.

Retinal detachment due to ocular involvement may cause unilateral visual loss.

Seizures and even death may result from cerebral involvement.

Toxocariasis diagnosis

Toxocariasis can be difficult to diagnose because the symptoms of toxocariasis are similar to the symptoms of other infections. If you think you or your child may have toxocariasis, you should see your health care provider to discuss the possibility of infection and, if necessary, to be examined.

Diagnosis of either visceral toxocariasis or ocular toxocariasis are based on the presence of signs of visceral toxocariasis or ocular toxocariasis and history of exposure to a potential source of infectious Toxocara eggs or larvae (e.g. in undercooked infected meat or offal). The diagnosis of visceral toxocariasis is based on compatible disease and exposure history with positive results by serological testing. The currently recommended test is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with larval stage antigens, usually excretory/secretory antigens are released when infective Toxocara larvae are cultured. The specificity of this assay is good although cross reactivity with antibody to the human roundworm, Ascaris lumbricoides, is possible; however, assays employing Toxocara excretory/secretory antigens minimize this problem. Positive serological results should be interpreted with consideration of the patient’s clinical status. Detectable antibody may be the result of infection in the past. Also, seropositivity can be present in asymptomatic Toxocara infection. Paired serum samples demonstrating a significant rise in antibody level over time may be useful to confirm active infection.

In ocular toxocariasis, Toxocara antibody levels in serum can be low or absent despite clinical disease. In some cases, Toxocara antibody can be detected in the aqueous or vitreous fluid samples from the affected eye and may be due to local antibody production or leakage of antibody from the circulation. The ocular fluid sample may be tested at a lower dilution than serum to improve ELISA sensitivity.

Signs and symptoms of visceral toxocariasis or ocular toxocariasis can be caused by the migrating larvae of other helminths, including Baylisascaris procyonis (both visceral toxocariasis and ocular toxocariasis), Strongyloides spp. (visceral toxocariasis), and Paragonimus spp. (visceral toxocariasis). Careful attention to disease course, exposure history and serological testing can be useful for differential diagnosis. For ocular toxocariasis, if a larva is visualized in the eye, measuring size may help differentiate the larger larvae of Baylisascaris from Toxocara or other larvae.

Toxocariasis treatment

Treatment with albendazole or mebendazole is indicated for visceral toxocariasis, although optimal duration of treatment is undefined. Both drugs are metabolized in the liver; prolonged use of albendazole (weeks to months) has led to development of pancytopenia in some patients with compromised liver function. Patients on long term treatment should be monitored by serial blood cell counts. However, albendazole has been used to treat millions of patients worldwide and in mass drug administration campaigns, and it is considered to be a safe drug with low toxicity record. In addition to antiparasitic therapy, symptomatic therapy including steroid treatment to control inflammation may be indicated.

| Drug | Dose and duration |

|---|---|

| Albendazole | 400 mg by mouth twice a day for five days (both adult and pediatric dosage) |

| Mebendazole | 100-200 mg by mouth twice a day for five days (both adult and pediatric dosage) |

Oral albendazole is available for human use in the United States.

Oral mebendazole is available for human use in the United States.

For ocular toxocariasis, the goal of treatment is to minimize damage to the eye. Systemic antiparasitic treatment with albendazole or mebendazole at the same doses as for visceral disease may be beneficial for active disease. Attempts to surgically remove the larva may be unsuccessful. Control of inflammation in the eye by use of topical or systemic steroids may be indicated. For patients with quiescent disease, improved outcomes may result from surgical intervention to prevent further damage due to chronic inflammation.

Albendazole

Treatment in pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C: Either studies in animals have revealed adverse effects on the fetus (teratogenic or embryocidal, or other) and there are no controlled studies in women or studies in women and animals are not available. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Albendazole is pregnancy category C. Data on the use of albendazole in pregnant women are limited, though the available evidence suggests no difference in congenital abnormalities in the children of women who were accidentally treated with albendazole during mass prevention campaigns compared with those who were not. In mass prevention campaigns for which the World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk, WHO allows use of albendazole in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of pregnancy. However, the risk of treatment in pregnant women who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

Treatment in breastfeeding

It is not known whether albendazole is excreted in human milk. Albendazole should be used with caution in breastfeeding women.

Treatment in children

The safety of albendazole in children less than 6 years old is not certain. Studies of the use of albendazole in children as young as one year old suggest that its use is safe. According to WHO guidelines for mass prevention campaigns, albendazole can be used in children as young as 1 year old. Many children less than 6 years old have been treated in these campaigns with albendazole, albeit at a reduced dose.

Mebendazole

Treatment in pregnancy

Pregnancy Category C: Either studies in animals have revealed adverse effects on the fetus (teratogenic or embryocidal, or other) and there are no controlled studies in women or studies in women and animals are not available. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

Mebendazole is in pregnancy category C. Data on the use of mebendazole in pregnant women are limited. The available evidence suggests no difference in congenital anomalies in the children of women who were treated with mebendazole during mass treatment programs compared with those who were not. In mass treatment programs for which the World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk, WHO allows use of mebendazole in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of pregnancy. The risk of treatment in pregnant women who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

Treatment in breastfeeding

It is not known whether mebendazole is excreted in breast milk. The WHO classifies mebendazole as compatible with breastfeeding and allows the use of mebendazole in lactating women.

Treatment in children

The safety of mebendazole in children has not been established. There is limited data in children age 2 years and younger. Mebendazole is listed as an intestinal antihelminthic medicine on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children, intended for the use of children up to 12 years of age.

Toxocariasis prognosis

The prognosis for visceral toxocariasis is generally good; however, chronic disease has potential correlations with both epilepsy and cognitive delay.

References- Winders WT, Menkin-Smith L. Toxocara Canis (Visceral Larva Migrans, Toxocariasis) [Updated 2019 Feb 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538524

- Sowemimo OA, Lee YL, Asaolu SO, Chuang TW, Akinwale OP, Badejoko BO, Gyang VP, Nwafor T, Henry E, Fan CK. Seroepidemiological study and associated risk factors of Toxocara canis infection among preschool children in Osun State, Nigeria. Acta Trop. 2017 Sep;173:85-89.

- Berrett AN, Erickson LD, Gale SD, Stone A, Brown BL, Hedges DW. Toxocara Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors in the United States. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017 Dec;97(6):1846-1850.

- Pak, K.Y., Park, S.W., Byon, I.S., & Lee, J.E. (2016). Ocular toxocariasis presenting as bilateral scleritis with suspect retinal granuloma in the nerve fiber layer: a case report. BMC Infectious Diseases.

- Ain Tiewsoh JB, Khurana S, Mewara A, Sehgal R, Singh A. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients with toxocariasis encountered at a tertiary care centre in North India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2018 Jul-Sep;36(3):432-434.

- Fakhri Y, Gasser RB, Rostami A, Fan CK, Ghasemi SM, Javanian M, Bayani M, Armoon B, Moradi B. Toxocara eggs in public places worldwide – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2018 Nov;242(Pt B):1467-1475.

- Woodhall DM, Fiore AE. Toxocariasis: A Review for Pediatricians. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2014 Jun;3(2):154-9.