Tungiasis

Tungiasis also known as sand flea disease, is a tropical parasitic skin disease caused by female sand fleas (Tunga penetrans, Siphonaptera: Tungidae, Tunginae) embedded in the skin of the host 1. The Tunga penetrans flea is also referred to as the chigoe, nigua, chica, pico, pique or suthi flea. Tungiasis affects millions of people in South America, the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa and predominantly affects children living in impoverished rural communities. In these settings tungiasis is associated with important morbidity.

Children and the elderly bear the highest tunga disease burden 2. In these population groups prevalence may be as high as 65%. Children frequently carry dozens of embedded sand fleas simultaneously 3. In endemic areas 95 to 98% of all tungiasis lesions occur at the feet 4. The toes, the sole and the heel are typical affected sites 5.

The female Tunga penetrans jigger flea penetrates into the skin of its host, undergoes a peculiar hypertrophy, expels several hundred eggs for a period of <3 weeks, and eventually dies. The shriveled carcass is then sloughed from the epidermis by host repair mechanisms 6. Within 10 days, the female Tunga penetrans jigger flea increases its volume by a factor of approximately 2,000, finally reaching the size of a pea 7. Through its hindquarters, which serve for breathing, defecating, and expulsing eggs, the flea remains in contact with the air, leaving a sore (240–500 μm) in the skin; the sore is an entry point for pathogenic microorganisms 8. The preferred localization for female Tunga penetrans jigger fleas is the periungual region of the toes, but lesions may occur on any part of the body 9.

Being a continuously enlarging and biologically active foreign body located in the epidermis, embedded sand fleas cause an intense inflammatory response 10. Bacterial superinfection is common and intensifies the inflammation 11. Intense pain and itching are almost constant 7. Frequent complications are suppuration, ulcers, deep fissures, periungual edema as well as deformation of nails and toes 5.

Tungiasis lesions can range from asymptomatic to pruritic to extremely painful. Note the following history findings:

- Travel to areas with tunga penetrans, including Central America, South America, India, and tropical Africa 12

- Walking along beach areas with bare feet or in sandals

- Pain or itching and papular or nodular eruptions, usually on the feet (although infection can occur on any area of the body to which the flea has access)

Although an effective and safe treatment exists it is not yet available in endemic countries 13. Therefore, embedded sand fleas are removed by inappropriate sharp and non-sterile instruments such as needles, safety pins or razor blades 14. This further increases the risk of bacterial superinfection and intense inflammation. Constant re-infection–as is the rule in endemic settings—impairs mobility, eventually leads to mutilation of the feet and immobilization of the patient. Anecdotal observations suggest that the restricted mobility may have a detrimental effect on household economics and impair school performance in children, mainly due to high absenteeism 14.

Tungiasis causes

Tungiasis (sand flea disease) is a parasitic skin disease caused by female sand fleas (Tunga penetrans) penetrated into the skin of humans or animals 15. Tungiasis is a zoonosis that affects a broad range of domestic and peridomestic animals, such as dogs, cats, pigs, and rats 16. Where humans live in close contact with these animals and where environmental factors and human behavior favor exposure, the risk for infection is high 17.

Numerous case reports detail the clinical aspects of tungiasis. However, they almost all exclusively describe travelers who have returned from the tropics with a mild disease 18. Having reviewed 14 cases of tungiasis imported to the United States, Sanushi 19 reported that the patients showed only one or two lesions and, that except for itching and local pain, no clinical pathology was observed. In contrast, older observations show that indigenous populations and recent immigrants, as well as deployed military personnel, frequently suffered from severe disease, characterized by deep ulcerations, tissue necrosis leading to denudation of bones, and auto-amputation of digits, resulting in physical disability, such as being unable to work and walk 20. Tungiasis has also been associated with lethal tetanus in nonvaccinated persons 21. In a study in São Paulo State, Brazil, tungiasis was identified as the place of entry in 10% of tetanus cases 22.

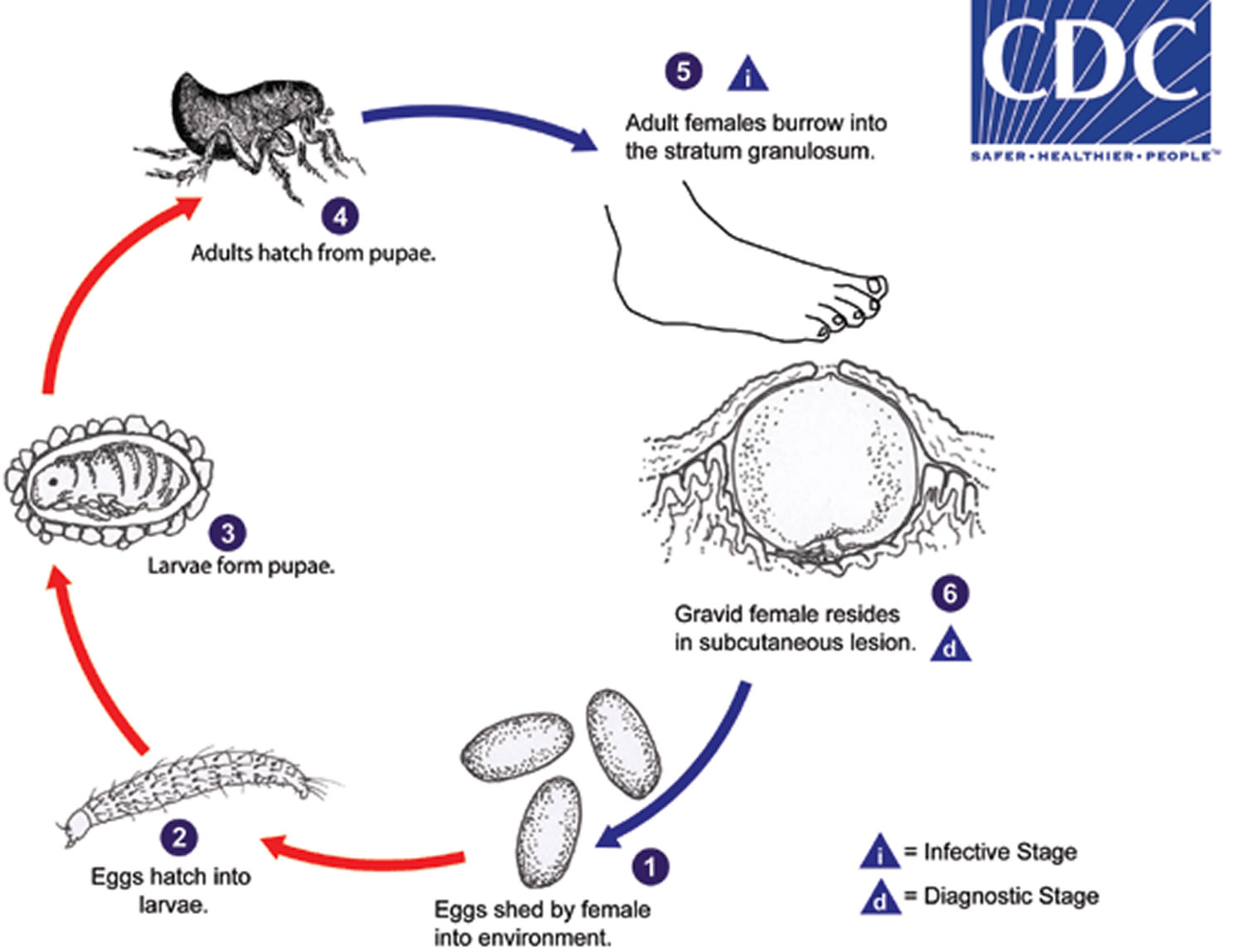

Tungiasis life cycle

Tunga penetrans is distributed in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, including Mexico to South America, the West Indies and Africa. The fleas normally occur in sandy climates, including beaches, stables and farms.

Tunga penetrans eggs are shed by the gravid female into the environment (number 1). Eggs hatch into larvae (number 2) in about 3-4 days and feed on organic debris in the environment. Tunga penetrans has two larval stages before forming pupae (number 3). The pupae are in cocoons that are often covered with debris from the environment (sand, pebbles, etc). The larval and pupal stages take about 3-4 weeks to complete. Afterwards, adults hatch from pupae (number 4) and seek out a warm-blooded host for blood meals. Both males and females feed intermittently on their host, but only mated females burrow into the skin (epidermis) of the host, where they cause a nodular swelling (number 5). Females do not have any specialized burrowing organs, and simply claw into the epidermis after attaching with their mouthparts. After penetrating the stratum corneum, they burrow into the stratum granulosum, with only their posterior ends exposed to the environment (number 6). The female fleas continue to feed and their abdomens extend up to about 1 cm. Females shed about 100 eggs over a two-week period, after which they die and are sloughed by the host’s skin. Secondary bacterial infections are not uncommon with tungiasis.

Figure 1. Tungiasis life cycle

Tungiasis prevention

Wearing shoes when travelling in endemic regions can easily prevent infestation. In some areas where the fleas are prevalent, spraying the ground with a insecticide such as malathion can significantly reduce the number of infestations.

Walking barefoot, especially in children, remains the most common reason why tungiasis remains prevalent in poor, rural populations.

Tungiasis symptoms

Due to the limited jumping ability of the tunga flea the most common site of infection is the feet. The lesion forms a punctum or ulceration, and is often described as a white patch with a black dot. The flea breathes through the opening of the lesion. The lesion can range from 4-10mm in diameter.

The lesions can be painful and very itchy, although in some cases there may be no symptoms. In some cases there may also be redness and swelling around the affected site.

The initial burrowing by the gravid tunga penetrans female fleas is usually painless; symptoms, including itching and irritation, usually start to develop as the tunga penetrans female fleas become fully-developed into the engorged state. Inflammation and ulceration may become severe, and multiple lesions in the feet can lead to difficulty in walking. To alleviate the pain patients avoid placing the whole foot on the ground while walking leading to a classical gait which is readily recognized as a tungiasis patient from a long distance 23. Secondary bacterial infections, including tetanus and gangrene, are not uncommon with tungiasis.

Tungiasis lesions were staged according to the Fortaleza classification and counted 7:

- Stage 1: penetrating sand flea

- Stage 2: brownish/black dot with a diameter of 1–2 mm

- Stage 3: circular yellow-white watch glass-like patch with a diameter of 3–10 mm and with a central black dot

- Stage 4: brownish-black crust with or without surrounding necrosis

Stage 1 to 3 are viable sand fleas; in stage 4 the parasite is dying or already dead 24.

Figure 2. Tungiasis

Footnote: Right foot of a 50-year-old man. All nails have been lost. Embedded fleas have been manipulated by the patient, leaving innumerable sores. Desquamation and ulceration are merged. The skin tends to bleed where the stratum corneum is eroded.

[Source 25 ]Figure 3. Severe tungiasis

Footnote: Extremely severe tungiasis. The sole is covered with several layers of embedded sand fleas on top of each other.

[Source 26 ]Figure 4. Tungiasis elbow

Footnote: A cluster of embedded tunga penetrans fleas at the elbow.

[Source 26 ]Figure 5. Tungiasis hand

Footnote: Ectopic localization of embedded tunga penetrans sand fleas in the palm of the hand.

[Source 26 ]Tungiasis complications

Secondary infections, such as bacteremia or septicemia, lymphangitis, tetanus, and gas gangrene, can occur. Among a native population in Brazil, the most common causes of bacterial superinfection included Staphylococcus aureus and various Enterobacteriaceae; anaerobic streptococci and Clostridium species were also found 27. Sores caused by burrowed fleas can be a potential entry point for clostridial and other infections, or these infections may follow attempts to extract the flea. Autoamputation of digits or other extensive soft tissue debridement is also a possibility.

Death from tetanus associated with tungiasis has been reported 28. For example, a case series from Haiti demonstrates a high incidence of tetanus in areas where the prevalence of tungiasis is high. In areas of Northeast Brazil, monthly incidence of tetanus cases has paralleled the seasonal variation of tungiasis. Thus, tetanus prophylaxis should be kept up to date in areas where tungiasis is common 29.

Conditions associated with tungiasis and its complications is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Spectrum of morbidity and complications in patients with very severe tungiasis

| Morbidity | Complication |

|---|---|

| Deformation of feet (clubfoot-like) | Immobility -> malnutrition -> starvation -> cachexia |

| Mutilation of toes | Loss/amputation of toes |

| Deep fissure, ulcers with extended necrosis of tissue (ulcère phagédénique) | Immobility -> malnutrition -> starvation -> cachexia; bacterial superinfection |

| Abscess, suppuration, phlegmone | Lymphangitis, septicemia -> death |

| Infection with Clostridia | Tissue necrosis, gangrene, tetanus -> death |

| Hyperkeratosis of sole | Embedded sand fleas are located in several layers on top of each other and cannot be removed surgically; immobility due to extreme pain |

| Inflammation of feet | Oedema -> pain -> immobility |

| Osteomyelitis | Loss of toes and limbs -> death |

| Anemia | Incapacity to work and to collect food -> malnutrition -> cachexia; heart failure |

Tungiasis diagnosis

Extraction of the gravid tunga penetrans flea using a sterile needle is diagnostic and therapeutic. A skin biopsy of a suspected papule or nodule may be performed.

In general, no laboratory studies are indicated other than a histologic examination of excised tissue to confirm the presence of the flea. No imaging studies are indicated unless there is a secondary infection with a complication such as gas gangrene.

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy (direct skin microscopy) may be helpful in identifying typical features, including an irregular, central, brown discoloration with a plugged opening in the middle or a gray-blue discoloration 30. Sometimes, a serosanguineous exudate oozes from the central opening, and eggs may be seen on microscopic examination.

Tungiasis treatment

In many cases tungiasis will heal on its own as the burrowed flea dies within 2 weeks and naturally sloughs off as the skin sheds. Over the 1-2 weeks whilst it feeds on the host’s blood the flea will lay more than 100 eggs that fall to the ground through the opening of the lesion.

Medical interventions include:

- physical removal of the flea using sterile forceps or needles. The opening needs to be enlarged and often when the flea is engorged it can be difficult to extract. In many cases the entire lesion needs to be cut out.

- application of topical anti-parasitic medications such as ivermectin, metrifonate, and thiabendazole.

- suffocation of the flea by applying a thick wax or jelly, and

- locally freezing the lesion using liquid nitrogen (cryotherapy).

All precautions should be taken to prevent secondary infections such as cellulitis, bacteremia, tetanus and gangrene. A course of oral antibiotics may be instituted if secondary infection is suspected. Ensure that tetanus prophylaxis is up to date.

Dimethicone

A two-component dimethicone, available under the brand name NYDA®, has been shown to cause 80%-95% of all embedded sand fleas to lose viability within seven days. It is most effective when applied topically directly to the affected area. Further, dimethicone is considered wholly nontoxic and very safe for extended human use 31.

Zanzarin

The insect repellant Zanzarin, a lotion consisting of coconut oil, jojoba oil, and aloe vera, was shown to reduce the number of newly embedded fleas and skin lesions, as well as to almost completely reverse the cutaneous pathology, when applied twice daily 32. In a study in Madagascar, a twice-daily application of Zanzarin was found to be much more effective than the use of closed toed shoes. It is believed that this is because shoes are less financially accessible and often not culturally desired 32. Zanzarin has now been removed from the market but is made of ingredients that could be accessed locally and so manufactured in areas affected by tungiasis.

Topical antibiotics and petroleum jelly

Topical ivermectin, metrifonate, and thiabendazole have been reported as effective. Occlusive petrolatum suffocates the organism. Twenty-percent salicylated petroleum jelly (Vaseline) applied 12-24 hours in profound infestations caused the death of the fleas and facilitated their manual removal 33. However, these treatments do not remove the flea from the skin, and they do not result in quick relief from painful lesions 34. When secondary infection is already present, an oral antibiotic should be considered 35. The primary complicating factor of tungiasis infection is the bacterial superinfections that can result from loss of integrity of the skin structures on the feet and thus a cellulitis and spreading infection. With repeated and extensive infections, pain and difficulty walking are significant contributors to morbidity.

References- Wiese S, Elson L, Feldmeier H. Tungiasis-related life quality impairment in children living in rural Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(1):e0005939. Published 2018 Jan 8. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005939 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5757912

- Ugbomoiko US, Ofoezie IE, Heukelbach J. Tungiasis: high prevalence, parasite load, and morbidity in a rural community in Lagos State, Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 2007. May;46(5):475–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03245.x

- Muehlen M, Heukelbach J, Wilcke T, Winter B, Mehlhorn H, Feldmeier H. Investigations on the biology, epidemiology, pathology and control of Tunga penetrans in Brazil. II. Prevalence, parasite load and topographic distribution of lesions in the population of a traditional fishing village. Parasitol Res. 2003. August;90(6):449–55. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0877-7

- Heukelbach J, Wilcke T, Eisele M, Feldmeier H. Ectopic localization of tungiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002. August;67(2):214–6.

- Feldmeier H, Eisele M, Van Marck E, Mehlhorn H, Ribeiro R, Heukelbach J. Investigations on the biology, epidemiology, pathology and control of Tunga penetrans in Brazil: IV. Clinical and histopathology. Parasitol Res. 2004. October;94(4):275–82. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1197-2

- Eisele M, Heukelbach J, van Marck E, Mehlhorn H, Meckes O, Franck S, Investigations on the biology, epidemiology, pathology and control of Tunga penetrans in Brazil: I. Natural history of tungiasis in man. Parasitol Res. 2003;90:87–99.

- Eisele M, Heukelbach J, Van Marck E, Mehlhorn H, Meckes O, Franck S, et al. Investigations on the biology, epidemiology, pathology and control of Tunga penetrans in Brazil: I. Natural history of tungiasis in man. Parasitol Res. 2003. June;90(2):87–99. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0817-y

- Feldmeier H, Heukelbach J, Eisele M, Sousa AQ, Barbosa LM, Carvalho CB, Bacterial superinfection in human tungiasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:559–64.

- Heukelbach J, Wilcke T, Eisele M, Feldmeier H. Ectopic localization of tungiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:214–6.

- Feldmeier H, Eisele M, Sabóia-Moura RC, Heukelbach J. Severe tungiasis in underprivileged communities: case series from Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003. August;9(8):949–55. doi: 10.3201/eid0908.030041

- Feldmeier H, Heukelbach J, Eisele M, Sousa AQ, Barbosa LMM, Carvalho CBM. Bacterial superinfection in human tungiasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2002. July 1;7(7):559–64.

- Rathe M, Rafn A, Poulsen T, Mohey R. [Tungiasis case after a trip to Kenya]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2009 Mar 2. 171(10):818.

- Nordin P, Thielecke M, Ngomi N, Mudanga GM, Krantz I, Feldmeier H. Treatment of tungiasis with a two-component dimeticone: a comparison between moistening the whole foot and directly targeting the embedded sand fleas. Trop Med Health [Internet]. 2017. March 10 [cited 2017 Jun 14];45 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5345134

- Feldmeier H, Sentongo E, Krantz I. Tungiasis (sand flea disease): a parasitic disease with particular challenges for public health. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol. 2013. January;32(1):19–26.

- Pampiglione S, Fioravanti ML, Gustinelli A, Onore G, Mantovani B, Luchetti A, et al. Sand flea (Tunga spp.) infections in humans and domestic animals: state of the art. Med Vet Entomol. 2009. September;23(3):172–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2009.00807.x

- Heukelbach J, Costa AML, Wilcke T, Mencke N, Feldmeier H. The animal reservoir of Tunga penetrans in poor communities in Northeast Brazil. Med Vet Entomol. 2003. In press.

- Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Tungiasis in poor communities of Northeast Brazil: an important public health problem. Public Health (Bayer). 2002;16:79–87

- Franck S, Wilcke T, Feldmeier H. Heukelbach. Tungiasis bei Tropenreisenden: eine kritische Bestandsaufnahme. Dtsch Arztebl. 2003. In press.

- Sanusi ID, Brown EB, Shepard TG, Granton WD. Tungiasis: report of one case and review of the 14 reported cases in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:941–4.

- Joyeux C, Sicé A. Précis de médecine coloniale. Paris: Edition Masson et Cte; 1937. p. 441.

- Tonge BL. Tetanus from chigger flea sores. J Trop Pediatr. 1989;35:94.

- Litvoc J, Leite RM, Katz G. Aspectos epidemiológicos do tétano no estado de São Paulo (Brasil). Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1991;33:477–84.

- Waterton C. Wanderings in South America, the north-west of the United States and the Antilles, in the years 1812, 1816, 1820 & 1824; London, 1825; 352 pages. Reprint 1973, Oxford University Press, p. 108–109 2nd ed. London: Printed for B. Fellowes,; 1828. 366 p.

- Kehr JD, Heukelbach J, Mehlhorn H, Feldmeier H. Morbidity assessment in sand flea disease (tungiasis). Parasitol Res. 2007. January;100(2):413–21. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0348-z

- Feldmeier, H., Eisele, M., Sabóia-Moura, R. C., & Heukelbach, J. (2003). Severe Tungiasis in Underprivileged Communities: Case Series from Brazil. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 9(8), 949-955. https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid0908.030041

- Miller H, Ocampo J, Ayala A, Trujillo J, Feldmeier H. Very severe tungiasis in Amerindians in the Amazon lowland of Colombia: A case series. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(2):e0007068. Published 2019 Feb 7. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007068 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6366737

- Feldmeier H, Heukelbach J, Eisele M, Sousa AQ, Barbosa LM, Carvalho CB. Bacterial superinfection in human tungiasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2002 Jul. 7(7):559-64.

- Pilger D, Schwalfenberg S, Heukelbach J, Witt L, Mehlhorn H, Mencke N, et al. Investigations on the biology, epidemiology, pathology, and control of Tunga penetrans in Brazil: VII. The importance of animal reservoirs for human infestation. Parasitol Res. 2008 Apr. 102(5):875-80.

- Joseph JK, Bazile J, Mutter J, Shin S, Ruddle A, Ivers L. Tungiasis in rural Haiti: a community-based response. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006 Oct. 100(10):970-4.

- Cabrera R, Daza F. Dermoscopy in the diagnosis of tungiasis. Br J Dermatol. 2009 May. 160(5):1136-7.

- Thielecke M, Nordin P, Ngomi N, Feldmeier H. Treatment of Tungiasis with dimeticone: a proof-of-principle study in rural Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014. 8 (7):e3058.

- Feldmeier H, Kehr JD, Heukelbach J. A plant-based repellent protects against Tunga penetrans infestation and sand flea disease. Acta Trop. 2006 Oct. 99(2-3):126-36.

- Clyti E, Couppie P, Deligny C, Jouary T, Sainte-Marie D, Pradinaud R. [Effectiveness of 20% salicylated vaseline in the treatment of profuse tungiasis. Report of 8 cases in French Guiana]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2003 Jan. 96(5):412-4.

- )Heukelbach J, Franck S, Feldmeier H. Therapy of tungiasis: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial with oral ivermectin. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004 Dec. 99(8):873-6.).

Other known treatments

Reported topical treatments for tungiasis include cryotherapy and electrodesiccation of the nodules. Application of formaldehyde, chloroform, or dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) to the infested skin has been used, but such treatments are not recommended and may cause patient morbidity.

Tungiasis prognosis

The prognosis of tungiasis is excellent if proper sterile methods are followed for the extraction of fleas and if extraction occurs soon after infection. Uncomplicated infestation results in pain, swelling, tenderness, and some limitation in mobility (although sometimes lesions are pruritic or even asymptomatic).

To prevent superinfection, tunga penetrans sand fleas should be surgically extracted immediately after penetration and the crater should be treated with topical antibiotic ((Feldmeier H, Heukelbach J, Eisele M, Sousa AQ, Barbosa LM, Carvalho CB. Bacterial superinfection in human tungiasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2002 Jul. 7(7):559-64.

- Gibbs SS. The diagnosis and treatment of tungiasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Sep. 159(4):981.