What is ulcerative colitis

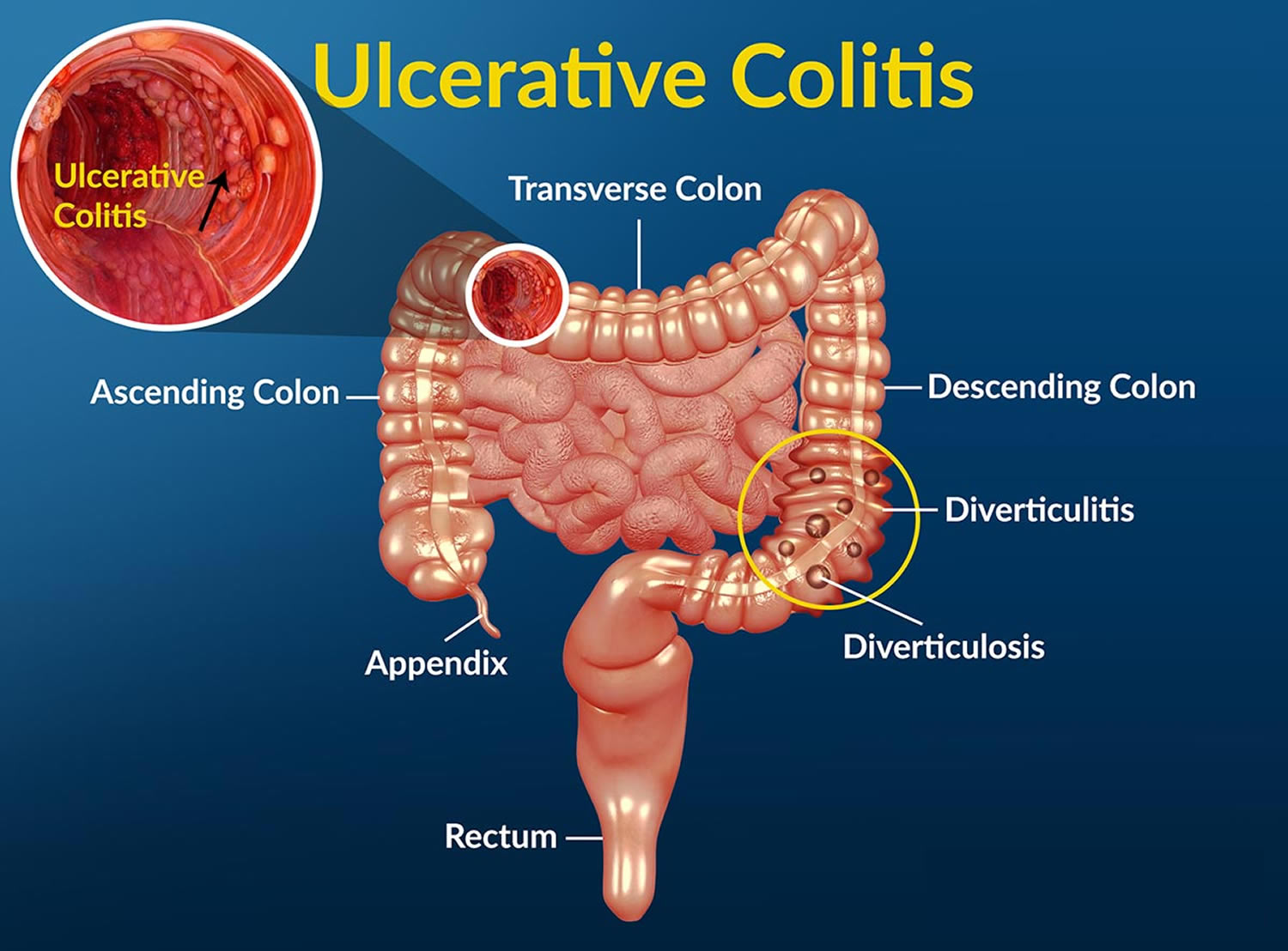

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic (long lasting), progressive, and disabling inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that causes inflammation—irritation or swelling—and ulcers (sores) on the inner lining of your large intestine (colon) and rectum. Crohn’s disease and microscopic colitis are other common types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Ulcerative colitis always involves the last part of the colon (the rectum). It can go higher up in the colon, up to involving the whole colon. Ulcerative colitis never has the “skip” areas typical of Crohn’s disease. That is damaged areas are continuous (not patchy) – usually starting at the rectum and spreading further into the colon. In ulcerative colitis the inflammation is present only in the innermost (deepest) layer of the lining of your large intestine (colon). Ulcerative colitis most often begins gradually and can become worse over time. However, it can also start suddenly. Symptoms can range from mild to severe and the symptoms may come and go. These occurrences are called flare-ups. In between periods of flare-ups—times when people have symptoms—most people have periods of remission—times when symptoms disappear. Periods of remission can last for weeks or years. Flare-ups can last many months and may come back at different times throughout your life. Typically, patients with ulcerative colitis experience periods of relapse and remission. Up to 90% will have one or more relapses after the first attack, and early relapse or active disease in the first 2 years is associated with a worse disease course subsequently 1. The goal of treatment is to keep people in remission long term.

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease of multifactorial origin whose cause and pathogenesis are not yet fully understood 2. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is more common in industrialized countries and in Western nations. The incidence is also increased in persons who live at higher latitudes 3. Worldwide and in less developed nations, ulcerative colitis is more common than Crohn’s disease, whereas in some studies of U.S. populations, the incidence of the two disorders is almost equal 3. Four percent of cases of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) cannot be characterized definitively as either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis; these patients are said to have indeterminate colitis if features are still indeterminate after colectomy histology is assessed 4. Inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified (IBD-U) is more common in children than adults 5. In a small proportion of ulcerative colitis patients their diagnosis is later changed to inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified (IBD-U) or Crohn’s disease 6.

Ulcerative colitis may affect as many as 907,000 Americans 7. The annual incidence of ulcerative colitis in the United States is between 9 and 12 cases per 100,000 persons 3. Men and women are equally likely to be affected (in contrast with Crohn’s disease, which has a higher incidence in women), and most people are diagnosed in their mid-30s. Ulcerative colitis can occur at any age (including infants) and older men are more likely to be diagnosed than older women.

While ulcerative colitis tends to run in families, researchers have been unable to establish a clear pattern of inheritance. Studies show that up to 20 percent of people with ulcerative colitis will also have a close relative with the disease. The disease is more common among white people of European origin and among people of Jewish heritage.

Ulcerative colitis can be debilitating and can sometimes lead to life-threatening complications. While it has no known cure, treatment can greatly reduce signs and symptoms of the disease and even bring about long-term remission.

To diagnose ulcerative colitis, doctors review medical and family history, perform a physical exam, and order medical tests. Doctors may use blood tests, stool tests, and endoscopy of the large intestine to diagnose ulcerative colitis.

Common Extraintestinal Manifestations of Ulcerative Colitis 8.

Approximately one-third of patients with ulcerative colitis have extraintestinal manifestations, which may be present even when the disease is inactive.

- Arthritis (21%)

- Aphthous stomatitis (4%)

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis (4%)

- Uveitis (4%)

- Erythema nodosum (3%)

- Ankylosing spondylitis (2%)

- Pyoderma gangrenosum (2%)

- Psoriasis (1%)

Researchers have not found that specific foods cause ulcerative colitis symptoms, although healthier diets appear to be associated with less risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Researchers have not found that specific foods worsen ulcerative colitis. Talk with your doctor about any foods that seem to be related to your symptoms. Your doctor may suggest keeping a food diary to help identify foods that seem to make your symptoms worse.

Depending on your symptoms and the medicines you take, your doctor may recommend changes to your diet. Your doctor may also recommend dietary supplements. Most people with ulcerative colitis receive care from a gastroenterologist, a doctor who specializes in digestive diseases. The goal of care is to keep people in remission long term.

See your doctor if you experience a persistent change in your bowel habits or if you have signs and symptoms such as:

- Abdominal pain

- Blood in your stool

- Ongoing diarrhea that doesn’t respond to over-the-counter medications

- Diarrhea that awakens you from sleep

- An unexplained fever lasting more than a day or two

Although ulcerative colitis usually isn’t fatal, it’s a serious disease that, in some cases, may cause life-threatening complications.

Who is more likely to develop ulcerative colitis?

Ulcerative colitis can occur in people of any age. However, it is more likely to develop in people:

- between the ages of 15 and 30 9, although the disease may develop in people of any age 10

- older than 60 11

- who have a family member (a parent, sibling, or child) with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

- of Jewish descent 12

8–14% of patients with ulcerative colitis have a family history of inflammatory bowel disease and first-degree relatives have four times the risk of developing the disease 13, 14. Jewish populations have higher rates of ulcerative colitis than other ethnicities 15, 16.

Types of ulcerative colitis

Doctors often classify ulcerative colitis according to its location. Types of ulcerative colitis include:

- Ulcerative proctitis. Inflammation is confined to the area closest to the anus (rectum), and rectal bleeding may be the only sign of the disease. This form of ulcerative colitis tends to be the mildest. For approximately 30% of all patients with ulcerative colitis, the illness begins as ulcerative proctitis. Because of its limited extent (usually less than the six inches of the rectum), ulcerative proctitis tends to be a milder form of ulcerative colitis. It is associated with fewer complications and offers a better outlook than more widespread disease.

- Proctosigmoiditis. Inflammation involves the rectum and sigmoid colon (lower end of the colon). Signs and symptoms include bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramps and pain, and an inability to move the bowels in spite of the urge to do so (tenesmus). Moderate pain on the lower left side of the abdomen may occur in active disease.

- Left-sided colitis. Inflammation extends from the rectum up through the sigmoid and descending colon. Signs and symptoms include bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramping and pain on the left side, and unintended weight loss.

- Pancolitis. Pancolitis often affects the entire colon and causes bouts of bloody diarrhea that may be severe, abdominal cramps and pain, fatigue, and significant weight loss. Potentially serious complications include massive bleeding and acute dilation of the colon (toxic megacolon), which may lead to an opening in the bowel wall. Serious complications may require surgery.

- Acute severe ulcerative colitis. This rare form of colitis affects the entire colon and causes severe pain, profuse diarrhea, bleeding, fever and inability to eat.

Ulcerative colitis classification

The Montreal classification in adults 17 and Paris classification in children 18 are useful in ascribing phenotypes to patients both for treatment and to assist with service delivery and research 19. Children developing ulcerative colitis generally have more extensive disease than adults 20. Establishing the extent of the inflammation in a patient with ulcerative colitis is important for prognosis as the likelihood of colectomy is dependent on disease extent. A systematic review showed that the 10 year colectomy rate is 19% for those with extensive colitis, 8% with left-sided colitis and 5% with proctitis; and male gender, young age and elevated inflammatory markers at diagnosis also increase the likelihood of colectomy 21. Backwash ileitis is also associated with more aggressive disease, and with primary sclerosing cholangitis 22. Those with extensive colitis also have the highest risk of developing colorectal cancer 23.

Disease extent can change after diagnosis 24. Up to half with proctitis or proctosigmoiditis will develop more extensive disease 21. Of patients with proctitis initially, 10% will ultimately have extensive colitis 25. However, over time the extent of inflammation can also regress, and classification should always remain as the maximal extent 24. Endoscopic appearance may significantly underestimate the true extent (particularly in quiescent ulcerative colitis), and this should be confirmed by mapping biopsies.

Table 1. Ulcerative Colitis Montreal and Paris classifications

| Montreal classification in adults 17 | Paris classification in children 18 | |||

| Extent* | E1 | Ulcerative proctitis | E1 | Ulcerative proctitis |

| E2 | Left-sided ulcerative colitis (distal to splenic flexure) | E2 | Left-sided ulcerative colitis (distal to splenic flexure) | |

| E3 | Extensive (proximal to splenic flexure) | E3 | Extensive (hepatic flexure distally) | |

| E4 | Pancolitis (proximal to hepatic flexure) | |||

| Severity | S0 | Clinical remission | S0 | Never severe† |

| S1 | Mild ulcerative colitis | S1 | Ever severe† | |

| S2 | Moderate ulcerative colitis | |||

| S3 | Severe ulcerative colitis | |||

Footnotes:

*Extent defined as maximal macroscopic inflammation.

†Severe defined by Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) ≥65.

[Source 26 ]Ulcerative Colitis disease activity

Definitions in relation to ulcerative colitis disease activity are shown in Table 2. The Mayo Score for ulcerative colitis is widely used in clinical trials and may be applied to clinical practice as a composite clinical and endoscopic tool 27. The Mayo disease activity score of 0–12 includes a measure of stool frequency, rectal bleeding, a physician’s global assessment and a measure of mucosal inflammation at endoscopy. The partial Mayo score uses the non-invasive components of the full score and correlates well to patient perceptions of response to therapy 28. Mayo Mayo disease activity score is the sum of scores for each of the four variables (maximum score 12). Disease activity: Mild 3–5; Moderate 6–10; Severe 11–12.

Table 2. Mayo disease activity score for ulcerative colitis

| Mayo index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stool frequency | Normal | 1–2/day more than normal | 3–4/day more than normal | 5/day more than normal |

| Rectal bleeding | None | Streaks of blood with stool <50% of the time | Obvious blood with stool most of time | Blood passed without stool |

| Mucosa (endoscopic subscore) | Normal or inactive disease | Mild disease (erythema, decreased vascular pattern, mild friability) | Moderate disease (marked erythema, lack of vascular pattern, friability, erosions) | Severe disease (spontaneous bleeding, ulceration) |

| Physician’s global assessment | Normal | Mild disease | Moderate disease | Severe disease |

Footnotes:

Clinical response: reduction of baseline Mayo score by ≥3 points and a decrease of 30% from the baseline score with a decrease of at least one point on the rectal bleeding subscale or an absolute rectal bleeding score of 0 or 1.

Clinical remission: defined as a Mayo score ≤2 and no individual subscore >1.

Mucosal healing: defined as a mucosa subscore of ≤1.

Disease activity: Mild 3–5; Moderate 6–10; Severe 11–12.

[Source 27 ]Endoscopic disease activity

There is wide variation in interpretation of ulcerative colitis disease activity endoscopically 29. The Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) has been developed to improve reliability (Table 3) 30. The Modified Mayo Endoscopic Score is another simple measure of endoscopic activity that correlates well with clinical and biological activity (Table 4) 31. Although both have been extensively validated, inter-observer variation remains a significant limitation for these visual scores 32.

Symptomatic and endoscopic scores may be limited by their ability to quantify accurately the impact of disease on quality of life, including fatigue and psychosocial function, or if complex the indices may be difficult to apply to clinical practice 33. An increasing emphasis on patient reported outcomes measures (PROMs: standardized questionnaires filled out by patients without clinician involvement) in clinical trials may translate to routine clinical practice 34.

Table 3. Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS)

| Descriptor (score most severe lesions) | Likert scale | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular pattern* | Normal (1) | Normal vascular pattern with arborisation of capillaries clearly defined, or with blurring or patchy loss of capillary margins |

| Patchy obliteration (2) | Patchy obliteration of vascular pattern | |

| Obliterated (3) | Complete obliteration of vascular pattern | |

| Bleeding* | None (1) | No visible blood |

| Mucosal (2) | Some spots or streaks of coagulated blood on the surface of the mucosa ahead of the scope, that can be washed away | |

| Luminal mild (3) | Some free liquid blood in the lumen | |

| Luminal moderate or severe (4) | Frank blood in the lumen ahead of endoscope or visible oozing from mucosa after washing intraluminal blood, or visible oozing from a hemorrhagic mucosa | |

| Erosions and ulcers* | None (1) | Normal mucosa, no visible erosions or ulcers |

| Erosions (2) | Tiny (≤5 mm) defects in the mucosa, of a white or yellow color with a flat edge | |

| Superficial ulcer (3) | Larger (>5 mm) defects in the mucosa, which are discrete fibrin-covered ulcers when compared with erosions, but remain superficial | |

| Deep ulcer (4) | Deeper excavated defects in the mucosa, with a slightly raised edge |

Footnotes:

UCEIS score = sum of all three descriptors in the worst affected area of the colon visible at endoscopy.

Remission, score ≤1.

*These three features account for 90% of variability in assessment of severity.

[Source 35 ]Table 4. Modified Mayo Endoscopic Score

| Ascending | Transverse | Descending | Sigmoid | Rectum | |

| Mayo endoscopic subscore: evaluated macroscopically at most severely inflamed part per segment (score 0–3: see table 2) | a | b | c | d | e |

| Maximal Extent (ME) in decimeters (during withdrawal) | ME | ||||

| Extended Modified Score (EMS) | EMS = (a+b+c+d+e) x ME | ||||

| Modified Mayo Endoscopic Score (MMES) | MMES=EMS/(number of segments with score >0) | ||||

Complications of ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis may lead to complications that develop over time, such as:

- Severe bleeding inside your colon (intestinal bleeding)

- A hole in the colon (perforated colon)

- Anemia, a condition in which you have fewer red blood cells than normal. Ulcerative colitis may lead to more than one type of anemia, including iron-deficiency anemia and anemia of inflammation or chronic disease.

- Severe dehydration

- Liver disease (rare)

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Bone problems, because ulcerative colitis and corticosteroids used to treat the disease can affect your bones. Bone problems include low bone mass, such as osteopenia or osteoporosis.

- Inflammation of your skin, joints and eyes

- An increased risk of colon cancer, because patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis that involves a third or more of the colon are at increased risk and require closer screening.

- A rapidly swelling colon (toxic megacolon)

- Increased risk of blood clots in veins and arteries

- Problems with growth and development in children, such as gaining less weight than normal, slowed growth, short stature, or delayed puberty.

In some cases, ulcerative colitis may lead to serious complications that develop quickly and can be life-threatening. These complications require treatment at a hospital or emergency surgery. Serious complications include:

- Fulminant ulcerative colitis, which causes extremely severe symptoms, such as more than 10 bloody bowel movements in a day, often with fever, rapid heart rate, and severe anemia 10. People with fulminant ulcerative colitis have a higher chance of developing other complications, such as toxic megacolon and perforation.

- Perforation, or a hole in the wall of the large intestine.

- Severe rectal bleeding or passing a lot of blood from the rectum. In some cases, people with ulcerative colitis may have severe or heavy rectal bleeding that may require emergency surgery.

- Toxic megacolon, which occurs when inflammation spreads to the deep tissue layers of the large intestine, and the large intestine swells and stops working.

Severe ulcerative colitis or serious complications may lead to additional problems, such as severe anemia and dehydration. These problems may require treatment at a hospital with blood transfusions or intravenous (IV) fluids and electrolytes.

Some people with ulcerative colitis also have inflammation in parts of the body other than the large intestine, including the:

- joints, causing certain types of arthritis

- skin

- eyes

- liver and bile ducts, causing conditions such as primary sclerosing cholangitis

People with ulcerative colitis also have a higher risk of blood clots in their blood vessels.

Fertility

The chances of a woman with ulcerative colitis becoming pregnant aren’t usually affected by the condition. However, infertility can be a complication of surgery carried out to create an ileo-anal pouch.

This risk is much lower if you have surgery to divert the small intestine through an opening in your abdomen (an ileostomy).

Pregnancy

The majority of women with ulcerative colitis who decide to have children will have a normal pregnancy and a healthy baby.

However, if you’re pregnant or planning a pregnancy you should discuss it with your care team. If you become pregnant during a flare-up, or have a flare-up while pregnant, there’s a risk you could give birth early (premature birth) or have a baby with a low birthweight.

For this reason, doctors usually recommend trying to get ulcerative colitis under control before getting pregnant.

Most ulcerative colitis medications can be taken during pregnancy, including corticosteroids, most 5-ASAs and some types of immunosuppressant medication.

However, there are certain medications (such as some types of immunosuppressant) that may need to be avoided as they’re associated with an increased risk of birth defects.

In some cases, your doctors may advise you to take a medicine that isn’t normally recommended during pregnancy. This might happen if they think the risks of having a flare-up outweigh the risks associated with the medicine.

Osteoporosis

People with ulcerative colitis are at an increased risk of developing osteoporosis, when the bones become weak and are more likely to fracture.

This isn’t directly caused by ulcerative colitis, but can develop as a side effect of the prolonged use of corticosteroid medication. It can also be caused by the dietary changes someone with the condition may take – such as avoiding dairy products, if they believe it could be triggering their symptoms.

If you’re thought to be at risk of osteoporosis, the health of your bones will be regularly monitored. You may also be advised to take medication or supplements of vitamin D and calcium to strengthen your bones.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis, where the bile ducts become progressively inflamed and damaged over time, is a rare complication of ulcerative colitis. Bile ducts are small tubes used to transport bile (digestive juice) out of the liver and into the digestive system.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis doesn’t usually cause symptoms until it’s at an advanced stage. Symptoms can include:

- fatigue (extreme tiredness)

- diarrhea

- itchy skin

- weight loss

- chills

- a high temperature (fever)

- yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes (jaundice)

There’s currently no specific treatment for primary sclerosing cholangitis, although medications can be used to relieve some of the symptoms, such as itchy skin. In more severe cases, a liver transplant may be required.

Toxic megacolon

Toxic megacolon is a rare and serious complication of severe ulcerative colitis, where inflammation in the colon causes gas to become trapped, resulting in the colon becoming enlarged and swollen.

This is potentially very dangerous as it can cause the colon to rupture (split) and cause infection in the blood (septicaemia).

The symptoms of a toxic megacolon include:

- abdominal (tummy) pain

- a high temperature (fever)

- a rapid heart rate

Toxic megacolon can be treated with fluids, antibiotics and steroids given intravenously (directly into a vein). If medications don’t improve the conditions quickly then surgical removal of the colon (known as a colectomy) may be needed.

Treating symptoms of ulcerative colitis before they become severe can help prevent toxic megacolon.

Colorectal cancer

People who have ulcerative colitis have an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer (cancer of the colon, rectum or bowel), especially if the condition is severe, started at a younger age or involves most of their large intestine (colon). The longer you have ulcerative colitis, the greater the risk. People have a higher risk for developing colorectal cancer if ulcerative colitis affects more of their large intestine, is more severe, started at a younger age, or has been present for a longer time. People with ulcerative colitis also have a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer if they have primary sclerosing cholangitis or have a family history of colorectal cancer 10.

People with ulcerative colitis are often unaware they have bowel cancer as the initial symptoms of this type of cancer are similar. These include:

- blood in the stools

- diarrhea

- abdominal pain

Therefore, you’ll usually have regular check-ups to look for signs of bowel cancer from about 8 years after your symptoms first develop 10.

If you have ulcerative colitis, your doctor may recommend a colonoscopy every 1 to 3 years to screen for colorectal cancer. Screening is testing for diseases when you have no symptoms. Screening can check for dysplasia—precancerous cells—or colorectal cancer. Diagnosing cancer early can improve chances for recovery.

For people with ulcerative colitis and primary biliary cholangitis, doctors typically recommend colonoscopies every year, starting at diagnosis 10.

Check-ups will involve examining your bowel with a colonoscope – a long, flexible tube containing a camera – that’s inserted into your rectum. The frequency of the colonoscopy examinations will increase the longer you live with the condition, and will also depend on factors such as how severe your ulcerative colitis is and if you have a family history of bowel cancer. This can vary between every one to three years, starting 8 years after ulcerative colitis started 10. For people with ulcerative colitis and primary biliary cholangitis, doctors typically recommend colonoscopies every year, starting at diagnosis 10.

To reduce the risk of bowel cancer, it’s important to:

- eat a healthy, balanced diet including plenty of fresh fruit and vegetables

- take regular exercise

- maintain a healthy weight

- avoid alcohol and smoking

Taking aminosalicylates as prescribed can also help reduce your risk of bowel cancer.

Ulcerative colitis causes

The exact cause of ulcerative colitis is unknown. Previously, diet and stress were suspected. However, researchers now know that these factors may aggravate but don’t cause ulcerative colitis. Researchers believe the following factors may play a role in causing ulcerative colitis:

- Overactive intestinal immune system

Scientists believe one cause of ulcerative colitis may be an abnormal immune reaction in the intestine. Normally, the immune system protects the body from infection by identifying and destroying bacteria, viruses, and other potentially harmful foreign substances. Researchers believe bacteria or viruses can mistakenly trigger the immune system to attack the inner lining of the large intestine. This immune system response causes the inflammation, leading to symptoms.

- Genes

Ulcerative colitis sometimes runs in families. Research studies have shown that certain abnormal genes may appear in people with ulcerative colitis. Genetic factors have a role in ulcerative colitis. Having a sibling with ulcerative colitis increases your risk of developing the disease 4.6-fold and the relative risk of one monozygotic twin having the disease is 95 times higher if the other twin is affected 36. However, researchers have not been able to show a clear link between the abnormal genes and ulcerative colitis.

- Microbiome

The microbes in your digestive tract—including bacteria, viruses, and fungi—that help with digestion are called the microbiome. Studies have found differences between the microbiomes of people who have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and those who don’t. Researchers are still studying the relationship between the microbiome and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

- Environment

Some studies suggest that certain things in the environment may increase the chance of a person getting ulcerative colitis, although the overall chance is low. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 11, antibiotics 11 and oral contraceptives 37 may slightly increase the chance of developing ulcerative colitis. A diet high in refined sugar, fat, and meat increases the risk, whereas a diet rich in vegetables reduces the risk 3, 38. Infection with nontyphoid Salmonella or Campylobacter is associated with an eight to 10 times higher risk of developing ulcerative colitis in the following year 39. The risk diminishes with time, but is still present up to 10 years later. The intestinal bacterial flora (microbiome) of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been shown to be markedly abnormal, but this finding has not yet led to therapeutic interventions 40.

The hygiene hypothesis states that excessive hygiene habits in Western industrialized nations prevent children from normal exposure to bacterial and helminthic antigens, thereby changing immune system responsiveness. Epidemiologic data provide indirect evidence for this theory, in the same way that they do for asthma and allergies 3.

Some people believe eating certain foods, stress, or emotional distress can cause ulcerative colitis. Emotional distress does not seem to cause ulcerative colitis. A few studies suggest that stress may increase a person’s chance of having a flare-up of ulcerative colitis. Also, some people may find that certain foods can trigger or worsen symptoms.

Researchers are still studying how people’s environments interact with genes, the immune system, and the microbiome to affect the chance of developing ulcerative colitis.

Risk factors for ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis affects about the same number of women and men. Risk factors may include:

- Age. Ulcerative colitis usually begins before the age of 30. But, it can occur at any age, and some people may not develop the disease until after age 60.

- Race or ethnicity. Although whites have the highest risk of the disease, it can occur in any race. If you’re of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, your risk is even higher.

- Family history. You’re at higher risk if you have a close relative, such as a parent, sibling or child, with the disease.

Ulcerative colitis signs and symptoms

Symptoms of ulcerative colitis a person experiences can vary depending on the severity of the inflammation and where it occurs in the intestine. Symptoms of ulcerative colitis may vary in severity. For example, mild symptoms may include having fewer than four bowel movements a day and sometimes passing blood with stool. Severe symptoms may include having more than six bowel movements a day and passing blood with stool most of the time. In extremely severe—or fulminant—ulcerative colitis, you may have more than 10 bloody bowel movements in a day 12.

When symptoms first appear, most people with ulcerative colitis have mild to moderate symptoms and about 10 percent of people can have severe symptoms, such as frequent, bloody bowel movements (hematochezia); fevers; and severe abdominal cramping 11.

The most common signs and symptoms of ulcerative colitis are diarrhea with blood, mucus or pus and abdominal pain and cramping.

Other signs and symptoms include:

- an urgent need to have a bowel movement even though your bowel may be empty (tenesmus)

- inability to defecate despite urgency

- cramping and pain in the abdomen

- feeling tired or fatigue

- nausea or loss of appetite

- weight loss

- fever

- anemia—a condition in which the body has fewer red blood cells than normal

- rectal pain

- rectal bleeding — passing small amount of blood with stool

- in children, failure to grow

Ulcerative colitis symptoms may cause some people to lose their appetite and eat less, and they may not get enough nutrients. In children, a lack of nutrients may play a role in problems with growth and development.

Less common symptoms include:

- joint pain or soreness

- eye irritation

- certain rashes.

Symptoms of ulcerative colitis may vary in severity. For example, mild symptoms may include having fewer than four bowel movements a day and sometimes passing blood with stool. Severe symptoms may include having more than six bowel movements a day and passing blood with stool most of the time. In extremely severe or fulminant ulcerative colitis, you may have more than 10 bloody bowel movements in a day 12.

Some symptoms are more likely to occur if ulcerative colitis is more severe or affects more of the large intestine. These symptoms include:

- fatigue, or feeling tired

- fever

- nausea or vomiting

- weight loss

You may have periods of remission—times when symptoms disappear—that can last for weeks or years. After a period of remission, you may have a relapse, or a return of symptoms.

Symptoms of ulcerative colitis flare-up

Some people may go for weeks or months with very mild symptoms, or none at all (known as remission), followed by periods where the symptoms are particularly troublesome (known as flare-ups or relapses).

During a ulcerative colitis flare-up, some people with ulcerative colitis also experience symptoms elsewhere in their body. For example, some people develop:

- painful and swollen joints (arthritis)

- mouth ulcers

- areas of painful, red and swollen skin

- irritated and red eyes

In severe cases, defined as having to empty your bowels six or more times a day, additional symptoms may include:

- shortness of breath

- a fast or irregular heartbeat

- a high temperature (fever)

- blood in your stools becoming more obvious

In most people, no specific trigger for flare-ups is identified, although a gut infection can occasionally be the cause. Stress is also thought to be a potential factor.

Ulcerative colitis diagnosis

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis cannot be established definitively by any single diagnostic study. Rather, it is made on the basis of an overall interpretation of the clinical signs, symptoms, laboratory tests, and endoscopic, histological, and radiological findings 41.

To diagnose ulcerative colitis, doctors review your medical and family history, perform a physical exam, and order medical tests. Doctors may use blood tests, stool tests, and endoscopy of the large intestine to diagnose ulcerative colitis.

The onset of symptoms can be sudden or gradual 42. The presence of anemia, thrombocytosis (too many platelets in blood), or hypoalbuminemia (the level of albumin in the blood is abnormally low) may suggest inflammatory bowel disease, but most patients with ulcerative colitis will not have these abnormalities 43. C-reactive protein (CRP) level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are relatively insensitive for detecting ulcerative colitis and should not be relied on to exclude inflammatory bowel disease. At the time of diagnosis, fewer than one-half of patients with ulcerative colitis have abnormal findings on these tests 44.

Endoscopic biopsy is used to confirm the diagnosis 45.

Elevated fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin levels have been proven sensitive for the detection of inflammatory bowel disease, but using these tests to exclude patients from endoscopic examination delays diagnosis in 6 to 8 percent of patients 44. Tests for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and anti– Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies are often positive in patients with ulcerative colitis, and can help distinguish the condition from Crohn’s disease in those with indeterminate histology 44. Approximately one-third of patients with ulcerative colitis have extraintestinal manifestations, which may be present even when the disease is inactive.

A health care provider diagnoses ulcerative colitis with the following:

- Medical and family history. To help diagnose ulcerative colitis, your doctor will ask about your symptoms, your medical history, and any medicines you take. Your doctor will also ask about lifestyle factors, such as smoking, and about your family medical history.

- Physical exam. During a physical exam, your doctor may:

- check your blood pressure, heart rate, and temperature—if you have ulcerative colitis, doctors may use these measures, along with information about your symptoms and test results, to find out how severe the disease is

- use a stethoscope to listen to sounds within your abdomen

- press on your abdomen to feel for tenderness or masses

- The physical exam may also include a digital rectal exam to check for blood in your stool.

- Lab tests

- Endoscopies of the large intestine

- X-ray. If you have severe symptoms, your doctor may use a standard X-ray of your abdominal area to rule out serious complications, such as a perforated colon.

- CT scan. A CT scan of your abdomen or pelvis may be performed if your doctor suspects a complication from ulcerative colitis. A CT scan may also reveal how much of the colon is inflamed.

- Computerized tomography (CT) enterography and magnetic resonance (MR) enterography. Your doctor may recommend one of these noninvasive tests if he or she wants to exclude any inflammation in the small intestine. These tests are more sensitive for finding inflammation in the bowel than are conventional imaging tests. MR enterography is a radiation-free alternative.

The health care provider may perform a series of medical tests to rule out other bowel disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease, or celiac disease, that may cause symptoms similar to those of ulcerative colitis.

Lab Tests

A health care provider may order lab tests to help diagnose ulcerative colitis, including blood and stool tests.

- Blood tests. A blood test involves drawing blood at a health care provider’s office or a lab. A lab technologist will analyze the blood sample. A health care provider may use blood tests to look for:

- anemia

- inflammation or infection somewhere in the body

- markers that show ongoing inflammation

- low albumin, or protein—common in patients with severe ulcerative colitis

- Stool tests. A stool test is the analysis of a sample of stool. A health care provider will give the patient a container for catching and storing the stool at home. The patient returns the sample to the health care provider or to a lab. A lab technologist will analyze the stool sample. Health care providers commonly order stool tests to rule out other causes of gastrointestinal diseases, such as infections that could be causing your symptoms. Doctors may also use stool tests to check for signs of inflammation in the intestines.

Endoscopies of the Large Intestine

Endoscopies of the large intestine are the most accurate methods for diagnosing ulcerative colitis and ruling out other possible conditions, such as Crohn’s disease, diverticular disease, or cancer. Doctors also use endoscopy to find out how severe ulcerative colitis is and how much of the large intestine is affected. Endoscopies of the large intestine include:

- Colonoscopy. A colonoscopy can show irritated and swollen tissue, ulcers, and abnormal growths such as polyps––extra pieces of tissue that grow on the inner lining of the intestine. If the gastroenterologist suspects ulcerative colitis, he or she will biopsy the patient’s colon and rectum. A biopsy is a procedure that involves taking small pieces of tissue for examination by a pathologist under a microscope.

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy. Flexible sigmoidoscopy is a test that uses a flexible, narrow tube with a light and tiny camera on one end, called a sigmoidoscope or scope, to look inside the rectum, the sigmoid colon, and sometimes the descending colon. In most cases, a patient does not need anesthesia. The health care provider will look for signs of bowel diseases and conditions such as irritated and swollen tissue, ulcers, and polyps.

Imaging procedures

- X-ray. If you have severe symptoms, your provider may use a standard X-ray of your abdominal area to rule out serious complications, such as a megacolon or a perforated colon.

- CT scan. A CT scan of your abdomen or pelvis may be performed if a complication from ulcerative colitis is suspected. A CT scan may also reveal how much of the colon is inflamed.

- Computerized tomography (CT) enterography and magnetic resonance (MR) enterography. These types of noninvasive tests may be recommended to exclude any inflammation in the small intestine. These tests are more sensitive for finding inflammation in the bowel than are conventional imaging tests. MR enterography is a radiation-free alternative.

Ulcerative colitis treatment

Ulcerative colitis treatment usually involves either drug therapy or surgery. Each person experiences ulcerative colitis differently, and doctors recommend treatments based on how severe ulcerative colitis is and how much of the large intestine is affected. Doctors most often treat severe and fulminant ulcerative colitis in a hospital.

Several categories of drugs may be effective in treating ulcerative colitis. The type you take will depend on the severity of your condition. The drugs that work well for some people may not work for others, so it may take time to find a medication that helps you. In addition, because some drugs have serious side effects, you’ll need to weigh the benefits and risks of any treatment.

Figure 1. Ulcerative colitis treatment (recommended treatment approach)

[Source 46]Active disease

For active disease distal to the descending colon, topical 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), including suppository and enema formulations, is the preferred treatment 47. Topical 5-ASA is more effective than oral 5-ASA or topical corticosteroid foams or enemas. Suppositories are effective for proctitis, whereas enemas are effective for disease that reaches as proximally as the splenic flexure 47. Topical mesalamine enemas, a common formulation of 5-ASA, induce remission in 72 percent of cases of active, left-sided ulcerative colitis within four weeks 48. Corticosteroid foams are also effective, although less so than 5-ASA. However, they may be easier to administer and more comfortable to retain 47. Oral 5-ASA is effective and may be preferred by patients who have difficulty with irritation or retaining topical formulations.18 A combination of oral and topical 5-ASA is superior to either formulation alone and should be used when other treatments are ineffective 49.

Oral 5-ASA is effective for mild to moderate active ulcerative colitis extending proximal to the sigmoid colon 50. If oral 5-ASA is ineffective, the addition of topical 5-ASA can be more effective than oral treatment alone 51. A short-term course of oral corticosteroids may be effective if the disease does not respond to combination 5-ASA therapy, or for patients in whom a more rapid response is desired 52. Infliximab (Remicade), an intravenously administered monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor-α, is effective for corticosteroid-refractory disease 53. A recent meta-analysis of studies of azathioprine (Imuran) for treatment of active ulcerative colitis showed no statistically significant effect 54.

Patients with severe to fulminant disease can be divided into those who require urgent hospitalization and those who may receive a trial of outpatient treatment. Signs and symptoms that suggest the need for urgent hospitalization include severe pain, abdominal or colonic distension, gastrointestinal bleeding, and toxicity (e.g., fever, tachycardia, leukocytosis, anemia). In patients who do not require urgent hospitalization, a trial of maximal dosage combined oral/topical 5-ASA therapy is recommended in conjunction with oral corticosteroids. If symptoms do not improve and the patient still does not require urgent hospitalization, the addition of infliximab as outpatient therapy is another option 46.

For patients who do not improve on maximal outpatient medical management or who have signs of toxicity, hospital admission and administration of intravenous corticosteroids reduce morbidity and mortality 55. If intravenous corticosteroids are ineffective after three to five days, intravenous cyclosporine (Sandimmune) or infliximab increases remission rates 56.

For patients who do not improve with the addition of cyclosporine or infliximab, there is evidence that switching to the other agent may decrease the risk of colectomy; however, this is associated with an increased risk of infectious complications, and the decision should be individualized 56. For patients with severe acute or chronic colitis who do not improve with medical therapy, surgical proctocolectomy is the next step. Proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis is most common; however, permanent ileostomy is also an option. Other indications for surgery are exsanguinating hemorrhage, perforation, or carcinoma 46. A recent systematic literature review showed that 12 months after surgery, health-related quality of life and health status are equivalent to that in the general population 57. Despite the potential benefits of surgery, complications are a concern. Colectomy is associated with a 54 percent reoperation rate for postsurgical complications 58. Pouchitis (inflammatory disease of the ileal pouchanal anastomosis pouch of unknown etiology) is also common 58.

Maintenance

Once remission is induced, the same agent is usually used to maintain remission. 5-ASA suppositories and enemas are effective for maintenance of distal disease 59. Oral 5-ASA is effective for extensive colitis.21 As with active disease, combined oral/topical therapy is more effective in maintaining remission than either agent alone 60. Corticosteroids are not effective in maintaining remission and have potentially serious adverse effects with long-term use 61. They should not be used for maintenance therapy. Azathioprine is an option for patients who require corticosteroids or cyclosporine for induction of remission or in whom remission is not adequately maintained with 5-ASA. However, it usually takes several months before it reaches full effect 62. For patients in whom remission was induced using infliximab, the same agent may be continued as maintenance therapy 53.

Ulcerative colitis medications

While no medication cures ulcerative colitis, many can reduce symptoms. Doctors prescribe medicines to reduce inflammation in the large intestine and to help bring on and maintain remission—a time when your symptoms disappear.

The goals of medication therapy are:

- inducing and maintaining remission

- improving the person’s quality of life

Many people with ulcerative colitis typically require medication therapy indefinitely (lifelong treatment), unless they have their colon and rectum surgically removed.

Which medicines your doctor prescribes will depend on how severe ulcerative colitis is. Ulcerative colitis medicines that reduce inflammation in the large intestine include:

- Aminosalicylates also called 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), which doctors prescribe to treat mild or moderate ulcerative colitis or to help people stay in remission.

- Corticosteroids also called steroids, which doctors prescribe to treat moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and to treat mild to moderate ulcerative colitis in people who don’t respond to aminosalicylates. Doctors typically don’t prescribe corticosteroids for long-term use or to maintain remission. Long-term use may cause serious side effects.

- Immunosuppressants, which doctors may prescribe to treat people with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and help them stay in remission. Doctors may also prescribe immunosuppressants to treat severe ulcerative colitis in people who are hospitalized and don’t respond to other medicines.

- Biologics, which doctors prescribe to treat people with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and help them stay in remission.

- A novel small molecule medicine (e.g., tofacitinib), which doctors may prescribe for adults with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis who don’t respond to other medicines or who have severe side effects with other medicines.

Table 5. Ulcerative Colitis medications

| Medication (form) | Dosage for active disease | Maintenance dosage | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine; oral) | 4 to 6 g per day in 4 divided doses | 2 to 4 g per day | Headache,† interstitial nephritis, nausea, vomiting |

| 5-Aminosalicylic acid (oral) | 2 to 4.8 g per day in 3 divided doses‡ | 1.2 to 2.4 g per day | Interstitial nephritis |

| 5-Aminosalicylic acid (suppository) | 1,000 mg once per day | 500 mg once or twice per day | Anal irritation, discomfort |

| 5-Aminosalicylic acid (enema) | 1 to 4 g per day | 2 to 4 g daily to every third day | Difficulty retaining, rectal irritation |

| Hydrocortisone (enema) | 100 mg | Not recommended | Difficulty retaining, rectal irritation |

| Hydrocortisone (10% foam) | 90 mg once or twice per day | Not recommended | Rectal irritation |

| Prednisone (oral) | 40 to 60 mg per day until clinical improvement, then taper by 5 to 10 mg per week | Not recommended | Adrenal suppression, bone disease,§ cataracts, cushingoid features, glaucoma, impaired wound healing, infections, metabolic abnormalities, peptic ulcers, psychiatric disturbances |

| Methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol; IV) | 40 to 60 mg per day | Not recommended | |

| Infliximab (Remicade; IV) | 5 to 10 mg per kg on weeks 0, 2, and 6 | 5 to 10 mg per kg every 4 to 8 weeks | Increased risk of infection and lymphoma, infusion reaction |

| Azathioprine (Imuran; oral) | Not recommended | 1.5 to 2.5 mg per kg per day|| | Allergic reactions, bone marrow suppression, infection, pancreatitis |

| Cyclosporine (Sandimmune; IV) | 2 to 4 mg per kg per day | Not recommended | Infection, nephrotoxicity, seizures |

| Lactobacillus GG (oral) | Not recommended | 18 × 109 viable bacteria per day | Minimal |

| Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (Mutaflor¶; oral) | Not recommended | 2.5 to 25 × 109 viable bacteria per day | Minimal |

Footnote: Medications are listed in order of preferred use, with first-line therapies listed first.

IV = intravenous.

†—Because of sulfapyridine moiety, which is not present in 5-aminosalicylic acid.

‡—Dosage for the newer multimatrix formulation is 2.4 to 4.8 g once per day.

§—Guidelines on prevention of complications related to long-term glucocorticoid therapy are available from the American College of Rheumatology at http://www.rheumatology.org/practice/clinical/guidelines/osteoupdate.asp.

||—May take three to six months to achieve full effectiveness.

¶—Not available in the United States but can be shipped from Canada.

[Source 63 ]Anti-inflammatory drugs

Anti-inflammatory drugs are often the first step in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. They include:

- 5-aminosalicylates also called 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA). Examples of this type of medication include sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), mesalamine (Asacol HD, Delzicol, others), balsalazide (Colazal) and olsalazine (Dipentum). Which one you take, and whether it is taken by mouth or as an enema or suppository, depends on the area of your colon that’s affected.

- Corticosteroids also known as steroids. These drugs, which include prednisone and hydrocortisone, are generally reserved for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis that doesn’t respond to other treatments. Due to the side effects, they are not usually given long term.

Immune system suppressors

These drugs also reduce inflammation, but they do so by suppressing the immune system response that starts the process of inflammation. For some people, a combination of these drugs works better than one drug alone.

Immunosuppressant drugs include:

- Azathioprine (Azasan, Imuran) and mercaptopurine (Purinethol, Purixan). These are the most widely used immunosuppressants for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Taking them requires that you follow up closely with your doctor and have your blood checked regularly to look for side effects, including effects on the liver and pancreas.

- Cyclosporine (Gengraf, Neoral, Sandimmune). This drug is normally reserved for people who haven’t responded well to other medications. Cyclosporine has the potential for serious side effects and is not for long-term use.

- Tofacitinib (Xeljanz). This is called a “small molecule” and works by stopping the process of inflammation. Tofacitinib is effective when other therapies don’t work. Main side effects include the increased risk of shingles infection and blood clots. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently issued a warning about tofacitinib, stating that preliminary studies show an increased risk of serious heart-related problems and cancer from taking this drug. If you’re taking tofacitinib for ulcerative colitis, don’t stop taking the medication without first talking with your doctor.

Biologics

This class of therapies targets proteins made by the immune system. Types of biologics used to treat ulcerative colitis include:

- Infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira) and golimumab (Simponi). These drugs, called tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, or biologics, work by neutralizing a protein produced by your immune system. They are for people with severe ulcerative colitis who don’t respond to or can’t tolerate other treatments.

- Vedolizumab (Entyvio). This medication was recently approved for treatment of ulcerative colitis for people who don’t respond to or can’t tolerate other treatments. It works by blocking inflammatory cells from getting to the site of inflammation.

- Ustekinumab (Stelara). This medication is approved for treatment of ulcerative colitis for people who don’t respond to or can’t tolerate other treatments. It works by blocking a different protein that causes inflammation.

Other medications

You may need additional medications to manage specific symptoms of ulcerative colitis. Always talk with your doctor before using over-the-counter medications.

He or she may recommend one or more of the following:

- Antibiotics. People with ulcerative colitis who run fevers will likely take antibiotics to help prevent or control infection.

- Anti-diarrheal medications. For severe diarrhea, loperamide (Imodium) may be effective. Use anti-diarrheal medications with great caution and after talking with your doctor, because they may increase the risk of toxic megacolon (enlarged colon).

- Pain relievers. For mild pain, your doctor may recommend acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) — but not ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve), and diclofenac sodium (Voltaren), which can worsen symptoms and increase the severity of disease.

- Antispasmodics. Sometimes doctors will prescribe antispasmodic therapies to help with cramps.

- Iron supplements. If you have chronic intestinal bleeding, you may develop iron deficiency anemia and be given iron supplements.

Surgery

Surgery can often eliminate ulcerative colitis. But that usually means removing your entire colon and rectum (proctocolectomy).

In most cases, this involves a procedure called ileal pouch anal anastomosis (J-pouch surgery). This procedure eliminates the need to wear a bag to collect stool. Your surgeon constructs a pouch from the end of your small intestine. The pouch is then attached directly to your anus, allowing you to expel waste relatively normally.

In some cases a pouch is not possible. Instead, surgeons create a permanent opening in your abdomen (ileal stoma) through which stool is passed for collection in an attached bag.

Your doctor may recommend surgery if you have:

- colorectal cancer

- dysplasia, or precancerous cells that increase the risk for developing colorectal cancer

- complications that are life-threatening, such as severe rectal bleeding, toxic megacolon, or perforation of the large intestine

- symptoms that don’t improve or stop after treatment with medicines

- symptoms that only improve with continuous treatment with corticosteroids, which may cause serious side effects when used for a long time.

To treat ulcerative colitis, surgeons typically remove the colon and rectum and change how your body stores and passes stool. The most common types of surgery for ulcerative colitis are:

- ileoanal reservoir surgery. Surgeons create an internal reservoir, or pouch, from the end part of the small intestine, called the ileum. Surgeons attach the pouch to the anus. Ileoanal reservoir surgery most often requires two or three operations. After the operations, stool will collect in the internal pouch and pass through the anus during bowel movements.

- ileostomy. Surgeons attach the end of your ileum to an opening in your abdomen called a stoma. After an ileostomy, stool will pass through the stoma. You’ll use an ostomy pouch—a bag attached to the stoma and worn outside the body—to collect stool.

Surgery may be laparoscopic or open. In laparoscopic surgery, surgeons make small cuts in your abdomen and insert special tools to view, remove, or repair organs and tissues. In open surgery, surgeons make a larger cut to open your abdomen.

If you are considering surgery to treat ulcerative colitis, talk with your doctor or surgeon about what type of surgery might be right for you and the possible risks and benefits.

Treating symptoms and complications of ulcerative colitis

Doctors may recommend or prescribe other treatments for symptoms or complications of ulcerative colitis. Talk with your doctor before taking any over-the-counter medicines.

To treat mild pain, doctors may recommend acetaminophen (paracetamol) instead of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). People with ulcerative colitis should avoid taking NSAIDs for pain because these medicines can make symptoms worse. NSAIDs include aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others), naproxen sodium (Aleve), diclofenac sodium (Voltaren) and others. While they do not cause ulcerative colitis, they can lead to inflammation of the bowel that makes ulcerative colitis worse.

To prevent or slow loss of bone mass and osteoporosis, doctors may recommend calcium and vitamin D supplements or medicines, if needed. For safety reasons, talk with your doctor before using dietary supplements or any other complementary or alternative medicines or practices.

Doctors most often treat severe complications in a hospital. Doctors may give:

- antibiotics, if severe ulcerative colitis or complications lead to infection

- blood transfusions to treat severe anemia

- IV fluids and electrolytes to prevent and treat dehydration

Doctors may treat life-threatening complications with surgery.

Cancer surveillance

Patients with ulcerative colitis have an increased risk of colorectal cancer. You will need more-frequent screening for colon cancer because of your increased risk. The recommended schedule will depend on the location of your disease and how long you have had it.

If your disease involves more than your rectum, you will require a surveillance colonoscopy every one to two years. Additionally, random biopsies spaced at regular intervals throughout the colon are recommended every one to two years during screening colonoscopies. Patients with proctitis or proctosigmoiditis do not seem to be at increased risk of cancer 46. You will need a surveillance colonoscopy beginning as soon as eight years after diagnosis if the majority of your colon is involved, or 15 years if only the left side of your colon is involved.

Foods to avoid with ulcerative colitis

Sometimes you may feel helpless when facing ulcerative colitis. But changes in your diet and lifestyle may help control your symptoms and lengthen the time between flare-ups. If you have ulcerative colitis, you should eat a healthy, well-balanced diet. Talk with your doctor or a registered dietitian about a healthy eating plan. Drink plenty of liquids. Try to drink plenty of liquids daily. Water is best. Alcohol and beverages that contain caffeine stimulate your intestines and can make diarrhea worse, while carbonated drinks frequently produce gas.

There’s no studies have suggested that diet can either cause or treat ulcerative colitis and there is no specific diet that patients with ulcerative colitis should follow, though it is advisable to eat a balanced diet 64. Likewise, there is no convincing evidence that ulcerative colitis results from food allergies. But certain foods and beverages can aggravate your signs and symptoms, especially during a flare-up.

It can be helpful to keep a food diary to keep track of what you’re eating, as well as how you feel. If you discover that some foods are causing your symptoms to flare, you can try eliminating them. Here are some suggestions that may help:

Foods to limit or avoid

- Limit dairy products. Many people with inflammatory bowel disease find that problems such as diarrhea, abdominal pain and gas improve by limiting or eliminating dairy products. You may be lactose intolerant — that is, your body can’t digest the milk sugar (lactose) in dairy foods. Using an enzyme product such as Lactaid may help as well.

- Limit fiber, if it’s a problem food. If you have inflammatory bowel disease, high-fiber foods, such as fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains, may make your symptoms worse. If raw fruits and vegetables bother you, try steaming, baking or stewing them.

In general, you may have more problems with foods in the cabbage family, such as broccoli and cauliflower, and nuts, seeds, corn and popcorn. Avoid other problem foods. Spicy foods, alcohol and caffeine may make your signs and symptoms worse.

Low-residue diet

Temporarily eating a low-residue or low-fiber diet can sometimes help improve symptoms of ulcerative colitis during a flare-up. These diets are designed to reduce the amount and frequency of the stools you pass.

Examples of foods that can be eaten as part of a low-residue diet include:

- white bread

- refined (non-wholegrain) breakfast cereals, such as cornflakes

- white rice, refined pasta and noodles

- cooked vegetables (but not the peel, seeds or stalks)

- lean meat and fish

- eggs

If you’re considering trying a low-residue diet, make sure you talk to your care team first.

Other dietary measures

- Eat small meals. You may find you feel better eating five or six small meals a day rather than two or three larger ones.

- Drink plenty of liquids. Try to drink plenty of fluids daily. Water is best. Alcohol and beverages that contain caffeine stimulate your intestines and can make diarrhea worse, while carbonated drinks frequently produce gas.

- Talk to a dietitian. If you begin to lose weight or your diet has become very limited, talk to a registered dietitian.

Ulcerative colitis diet

In studies involving people with chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, the anti-Inflammatory diet (IBD-AID) has been used as an adjunct dietary therapy for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) 65. The goal of the anti-Inflammatory diet (IBD-AID) is to assist with a decreased frequency and severity of flares, obtain and maintain remission in people with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Dysbiosis, or altered bacterial flora, is one of the theories behind the development of anti-Inflammatory diet (IBD-AID), in that certain carbohydrates in the lumen of the gut provide pathogenic bacteria a substrate on which to proliferate 66, 67.

The anti-Inflammatory diet (IBD-AID) has five basic components:

- The first of which is the modification of certain carbohydrates, (including lactose, and refined or processed complex carbohydrates)

- The second places strong emphasis on the ingestion of pre- and probiotics (e.g.; soluble fiber, leeks, onions, and fermented foods) to help restore the balance of the intestinal flora 68, 69, 70

- The third distinguishes between saturated, trans, mono- and polyunsaturated fats 71, 72,

- The fourth encourages a review of the overall dietary pattern, detection of missing nutrients, and identification of intolerances.

- The last component modifies the textures of the foods (e.g.; blenderized, ground, or cooked) as needed (per patient symptomology) to improve absorption of nutrients and minimize intact fiber.

The phases indicated in Table 6 are examples of the modification of texture complexity, so that dietitian and patient can expand the diet as the patient’s tolerance and absorption improves. Some sensitivities common to many patients (not just those with IBD), are eased through supplementation of digestive enzymes or avoidance. A senior dietitian advised the patient and either family or spouse regarding the details of the diet during regular clinic visits. Patients taking supplements (probiotics, vitamin/minerals, omega-3 fatty acids) were advised to continue or discontinue, depending on the needs of the individual and the dietary intake 73.

The anti-Inflammatory diet (IBD-AID) consists of lean meats, poultry, fish, omega-3, eggs, particular sources of carbohydrate, select fruits and vegetables, nut and legume flours, limited aged cheeses (made with active cultures and enzymes), fresh cultured yogurt, kefir, miso and other cultured products (rich with certain probiotics) and honey. Prebiotics, in the form of soluble fiber (containing beta-glucans and inulin, such as bananas, oats, blended chicory root, and flax meal) are suggested. In addition, the patient is advised to begin at a texture phase of the diet matching with symptomology, starting with phase one if in an active flare. Many patients require foods to be softened and textures mechanically altered by pureeing the foods, and avoiding foods with stems and seeds when starting the diet (see phases 1–3 of Table 6), as intact fiber can be problematic for those with strictures and highly active mucosal inflammation. Some patients will require lifelong avoidance of intact fiber. Food irritants are not limited to intact fiber, but may include certain foods, processing agents and flavorings to which IBD patients may be reactive.

Table 6. The Anti-Inflammatory Diet (IBD-AID) Food Phase chart

| Phase type | Phase I | Phase II | Phase III | Phase IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soft, well-cooked or cooked then pureed foods, no seeds | Soft Textures: well-cooked or pureed foods, no seeds, choose floppy or tender foods | May still need to avoid stems, choose floppy greens or other greens depending on individual tolerance | If in remission with no strictures | |

| Vegetables | Butternut Squash, Pumpkin, Sweet Potatoes, Onions | Carrots, Zucchini, Eggplant, Peas, Snow peas, Spaghetti squash, Green beans, Yellow beans, Microgreens (2 week old baby greens), Watercress, Arugula, Fresh flat leaf parsley and cilantro, Seaweed, Algae | Butter lettuce, Baby spinach, Peeled cucumber, Olives, Leeks Bok Choy, Bamboo shoots, Collard greens, Beet greens, Sweet peppers, Kale, Fennel bulb | Artichokes, Asparagus, Tomatoes, Lettuce, Brussels sprouts, Beets, Cabbage, Kohlrabi, Rhubarb, Pickles, Spring onions, Water chestnuts, Celery, Celeriac, Cauliflower, Broccoli, Radish, Green pepper, Hot pepper |

| Pureed vegetables: Mushrooms, Phase II vegetables (pureed) | Pureed vegetables: all except cruciferous | Pureed vegetables: all from Phase IV, Kimchi | ||

| Fruits | Banana, Papaya, Avocado, Pawpaw | Watermelon (seedless), Mangoes, Honeydew, Cantaloupe, May need to be cooked: Peaches, Plums, Nectarines, Pears, (Phase III fruits are allowed if pureed and seeds are strained out) | Strawberries, Cranberries, Blueberries, Apricots, Cherries, Coconut, Lemons, Limes, Kiwi, Passion fruit, Blackberries, Raspberries, Pomegranate (May need to strain seeds from berries) | Grapes, Grapefruit, Oranges, Currants, Figs, Dates, Apples (best cooked), Pineapple, Prunes |

| Meats and fish | All fish (no bones), Sardines (small bones ok), Turkey and ground beef, Chicken, Eggs | Scallops | Lean cuts of Beef, Lamb, Duck, Goose | Shrimp, Prawns, Lobster |

| Non dairy unsweetened | Coconut milk, Almond milk, Oat milk, Soy milk | |||

| Dairy, unsweetened | Yogurt, Kefir | Farmers cheese (dry curd cottage cheese), Cheddar cheese | Aged cheeses | |

| Nuts/Oils/Legumes/Fats | Miso (refrigerated), Tofu, Olive oil, Canola oil, Flax oil, Hemp oil, Walnut oil, Coconut oil | Almond flour, Peanut flour, Soy flour, Sesame oil, Grapeseed oil, Walnut oil, Pureed nuts, Safflower oil, Sunflower oil | Whole nuts, Soybeans, Bean flours, Nut butters, Well-cooked lentils (pureed), Bean purees (e.g. hummus) | Whole beans and lentils |

| Grains | Ground flax or Chia Seeds (as tolerated) | Steel cut oats (well-cooked as oatmeal) | Rolled well-cooked oats | |

| Spices | Basil, Sage, Oregano, Salt, Nutmeg, Cumin, Cinnamon, Turmeric, Saffron, Mint, Bay leaves, Tamari (wheat free soy sauce), Fenugreek tea, Fennel tea, Vanilla | Dill, Thyme, Rosemary Tarragon, Cilantro, Basil, Parsley | Mint, Ginger, Garlic (minced), Paprika, Chives, Daikon, Mustard | Wasabi, Tamarind, Horseradish, Fenugreek, Fennel |

| Sweeteners | Stevia, Maple syrup, Honey (local), Unsweetened fruit juice | Lemon and lime juice | ||

| Misc. | Capsule or liquid supplements, Cocoa powder | Baking powder (no cornstarch), Baking soda, Unflavored gelatin | Ghee, Light mayonnaise, Vinegar | Ketchup (sugar free), Hot sauce (sugar free) |

Inflammatory bowel disease dietary guidelines

To help patients navigate their nutritional questions, the International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases recently reviewed the best current evidence to develop expert recommendations regarding dietary measures that might help to control and prevent relapse of inflammatory bowel disease 74. In particular, the International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases focused on the dietary components and additives that they felt were the most important to consider because they comprise a large proportion of the diets that inflammatory bowel disease patients may follow. Furthermore, the recent International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases guidelines are an excellent starting point for discussions between patients and their doctors about whether specific dietary changes might be helpful in reducing symptoms and risk of relapse of inflammatory bowel disease. However, all patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should work with their doctor or a nutritionist, who will conduct a nutritional assessment to check for malnutrition and provide advice to correct deficiencies if they are present.

The International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases recommendations were developed with the aim of reducing symptoms and inflammation 74. The ways in which altering the intake of particular foods may trigger or reduce inflammation are quite diverse, and the mechanisms are better understood for certain foods than others. For example, fruits and vegetables are generally higher in fiber, which is fermented by bacterial enzymes within the colon. This fermentation produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that provide beneficial effects to the cells lining the colon. Patients with active IBD have been observed to have decreased short-chain fatty acids, so increasing the intake of plant-based fiber may work, in part, by boosting the production of short-chain fatty acids. However, it is important to note disease-specific considerations that might be relevant to your particular situation. For example, about one-third of Crohn’s disease patients will develop an area of intestinal narrowing, called a stricture, within the first 10 years of diagnosis. Insoluble fiber can worsen symptoms and, in some cases, lead to intestinal blockage if a stricture is present. So, while increasing consumption of fruits and vegetable is generally beneficial for Crohn’s disease, patients with a stricture should limit their intake of insoluble fiber.

Table 7. The International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases guidelines

| Food | If you have Crohn’s disease | If you have ulcerative colitis |

| Fruits | increase intake | insufficient evidence |

| Vegetables | increase intake | insufficient evidence |

| Red/processed meat | insufficient evidence | decrease intake |

| Unpasteurized dairy products | best to avoid | best to avoid |

| Dietary fat | decrease intake of saturated fats and avoid trans fats | decrease consumption of myristic acid (palm, coconut, dairy fat), avoid trans fats, and increase intake of omega-3 (from marine fish but not dietary supplements) |

| Food additives | decrease intake of maltodextrin-containing foods | decrease intake of maltodextrin-containing foods |

| Thickeners | decrease intake of carboxymethylcellulose | decrease intake of carboxymethylcellulose |

| Carrageenan (a thickener extracted from seaweed) | decrease intake | decrease intake |

| Titanium dioxide (a food colorant and preservative) | decrease intake | decrease intake |

| Sulfites (flavor enhancer and preservative) | decrease intake | decrease intake |

What are specific diets for inflammatory bowel disease?

A number of specific diets have been explored for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including the Mediterranean diet, specific carbohydrate diet, Crohn’s disease exclusion diet, autoimmune protocol diet, and a diet low in fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs). Although the International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases group initially set out to evaluate some of these diets, they did not find enough high-quality trials that specifically studied them 74. Therefore, they limited their recommendations to individual dietary components. Stronger recommendations may be possible once additional trials of these dietary patterns become available. For the time being, patients are to monitor for correlations of specific foods to their symptoms. In some cases, patients may explore some of these specific diets to see if they help.

Stress relief

Although stress doesn’t cause inflammatory bowel disease, it can make your signs and symptoms worse and may trigger flare-ups.

Successfully managing stress levels may reduce the frequency of symptoms. The following advice may help:

To help control stress, try:

- Exercise. Even mild exercise can help reduce stress, relieve depression and normalize bowel function. Talk to your doctor about an exercise plan that’s right for you.

- Biofeedback. This stress-reduction technique helps you reduce muscle tension and slow your heart rate with the help of a feedback machine. The goal is to help you enter a relaxed state so that you can cope more easily with stress.

- Regular relaxation and breathing exercises. An effective way to cope with stress is to perform relaxation and breathing exercises. You can take classes in yoga and meditation or practice at home using books, CDs or DVDs.

Emotional impact

Living with a long-term condition that is as unpredictable and potentially debilitating as ulcerative colitis can have a significant emotional impact.

In some cases, anxiety and stress caused by ulcerative colitis can lead to depression. Signs of depression include feeling very down, hopeless and no longer taking pleasure in activities you used to enjoy. If you think you might be depressed, contact your doctor for advice.

You may also find it useful to talk to others affected by ulcerative colitis, either face-to-face or via the internet. Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation 75 is a good resource, with details of local support groups and a large range of useful information on ulcerative colitis and related issues.

Alternative medicine

Many people with digestive disorders have used some form of complementary and alternative therapy.

Some commonly used therapies include:

- Herbal and nutritional supplements. The majority of alternative therapies aren’t regulated by the FDA. Manufacturers can claim that their therapies are safe and effective but don’t need to prove it. What’s more, even natural herbs and supplements can have side effects and cause dangerous interactions. Tell your doctor if you decide to try any herbal supplement.

- Probiotics. Researchers suspect that adding more of the beneficial bacteria (probiotics) that are normally found in the digestive tract might help combat the disease 76. Lactobacillus GG and Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (Mutaflor) have been shown to be as effective as 5-ASA for maintenance therapy 77, 78. Although research is limited, there is some evidence that adding probiotics along with other medications may be helpful, but this has not been proved.

- Fish oil. Fish oil acts as an anti-inflammatory, and there is some evidence that adding fish oil to aminosalicylates may be helpful, but this has not been proved.

- Aloe vera. Aloe vera gel may have an anti-inflammatory effect for people with ulcerative colitis, but it can also cause diarrhea.

- Acupuncture. Only one clinical trial 79 has been conducted regarding its benefit. The procedure involves the insertion of fine needles into the skin, which may stimulate the release of the body’s natural painkillers.

- Turmeric. Curcumin, a compound found in the spice turmeric, has been combined with standard ulcerative colitis therapies in clinical trials. There is some evidence of benefit, but more research is needed.

- Wheatgrass has also shown some effectiveness in reducing symptoms of active disease 80.

Ulcerative colitis prognosis