Unconjugated bilirubin

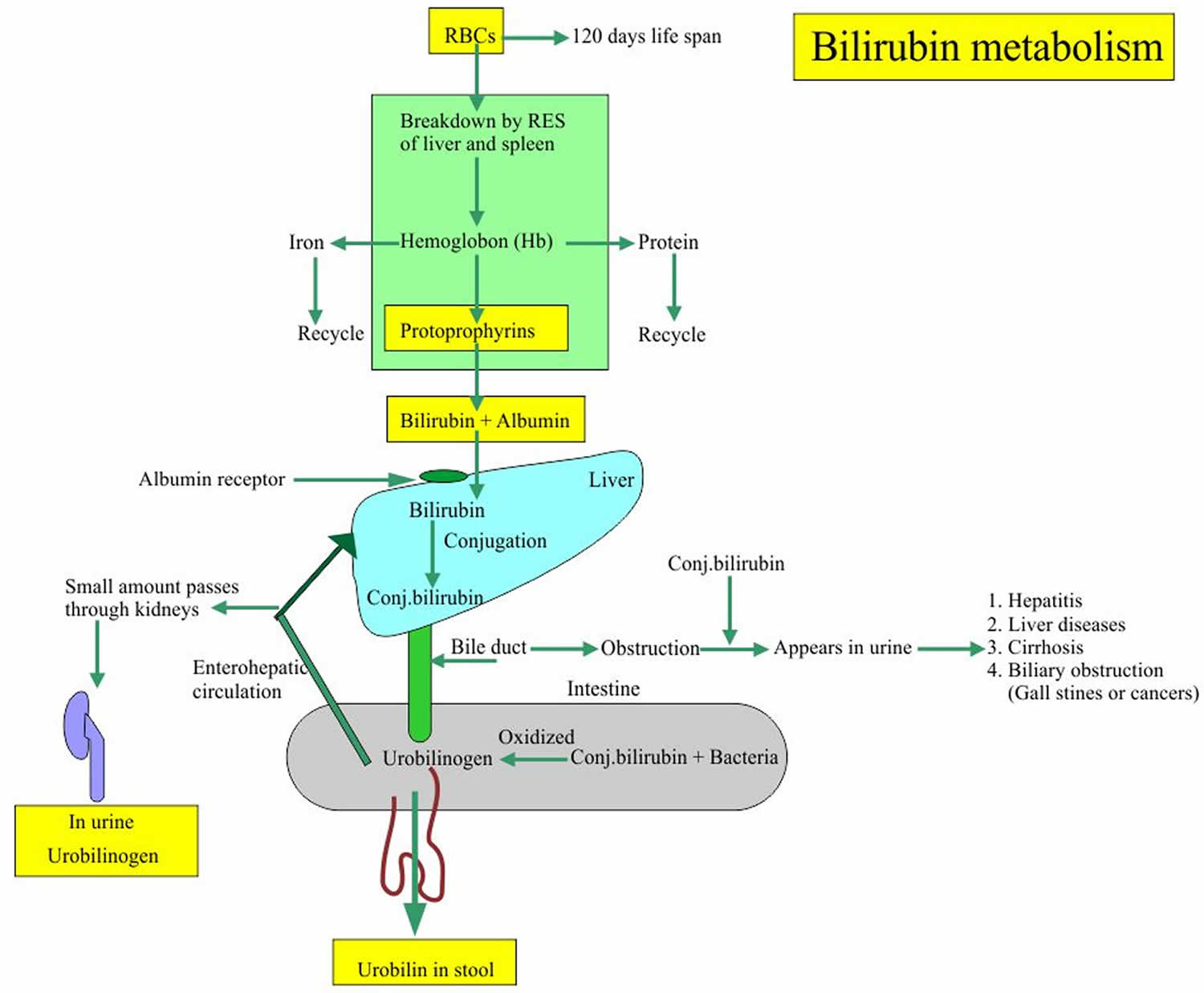

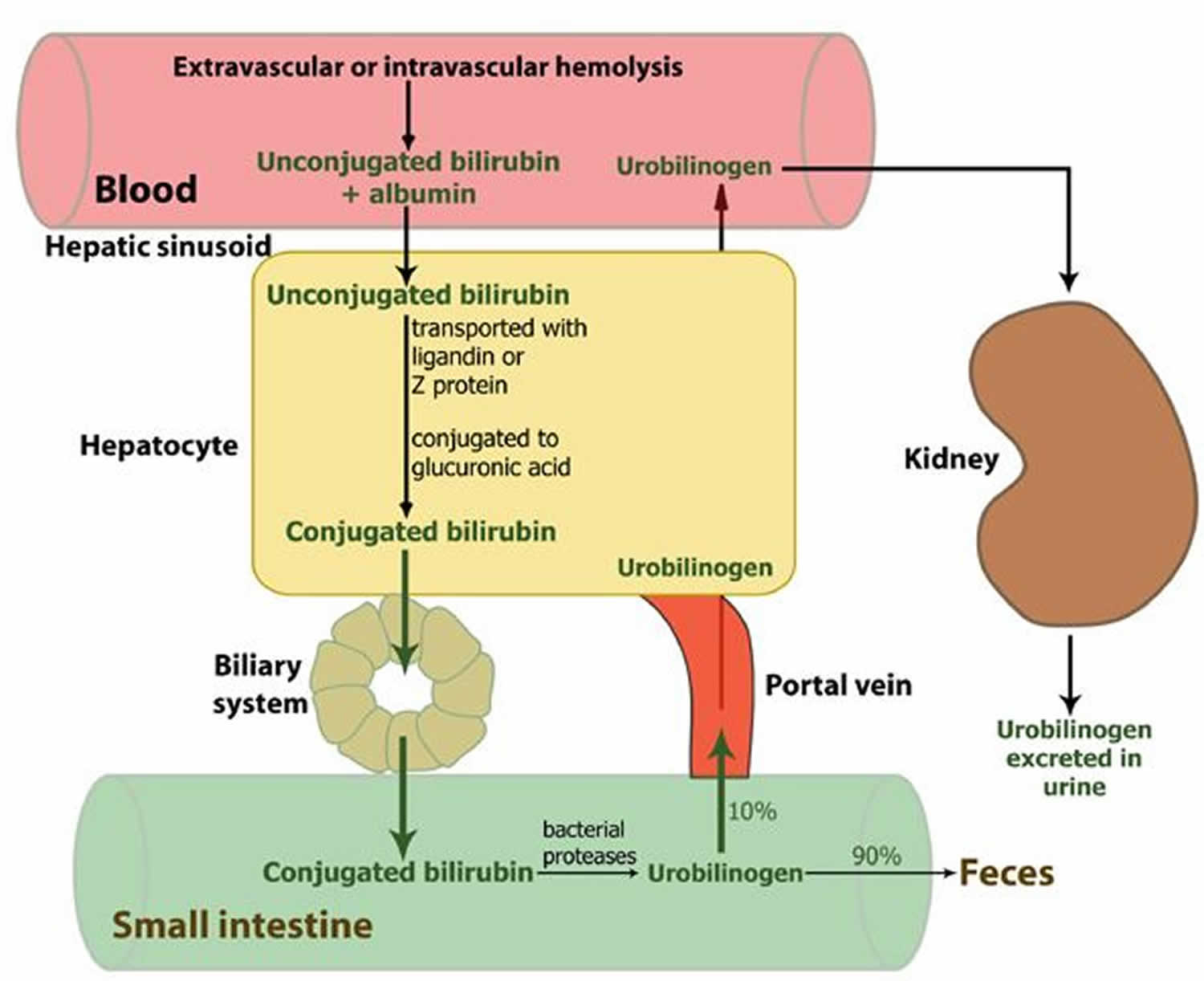

Unconjugated bilirubin also known as indirect bilirubin, is a fat-soluble form of bilirubin that is formed during the initial chemical breakdown of hemoglobin and while being transported in the blood, is mostly bound to albumin to the liver. The binding affinity for albumin to bilirubin is extremely high, and under ideal conditions, no free (non-albumin bound) unconjugated bilirubin is seen in the plasma 1. Binding of albumin limits the escape of bilirubin from the vascular space, minimizes glomerular filtration, and prevents its precipitation and deposition in tissues. When the albumin-unconjugated bilirubin complex reaches the liver, sugars are attached (conjugated) to the unconjugated bilirubin to form water soluble conjugated bilirubin (bilirubin mono- and diglucuronide) also known as direct bilirubin. Conjugated bilirubin are then excreted in the bile and passes from the liver to the small intestines; there, it is further broken down by bacteria and eventually eliminated in the stool. Thus, the breakdown products of bilirubin give stool its characteristic brown color.

Bilirubin is not normally present in the urine. However, conjugated bilirubin is water-soluble and may be eliminated from the body through the urine if it cannot pass into the bile. Measurable bilirubin in the urine usually indicates blockage of liver or bile ducts, hepatitis, or some other form of liver damage and may be detectable early in disease; for this reason, bilirubin testing is integrated into common dipstick testing used for routine urinalysis.

Bilirubin is a potentially toxic substance. A level of bilirubin in the blood of 2.0 mg/dL can lead to jaundice. Jaundice is a yellow color in the skin, mucus membranes, or eyes.

Jaundice is the most common reason to check bilirubin level. Low levels of bilirubin are generally not concerning and are not monitored.

In adults and older children, bilirubin is measured to:

- Diagnose and/or monitor diseases of the liver and bile duct (e.g., cirrhosis, hepatitis, or gallstones)

- Evaluate people with sickle cell disease or other causes of hemolytic anemia; these people may have episodes called crises when excessive RBC destruction increases bilirubin levels.

In newborns with jaundice (most newborns have some jaundice), bilirubin is used to distinguish the causes of jaundice.

- In both physiologic jaundice of the newborn and hemolytic disease of the newborn, only unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin is increased.

- In much less common cases, damage to the newborn’s liver from neonatal hepatitis and biliary atresia will increase conjugated (direct) bilirubin concentrations as well, often providing the first evidence that one of these less common conditions is present.

It is important that an elevated level of bilirubin in a newborn be identified and quickly treated because excessive unconjugated bilirubin damages developing brain cells. The consequences of this damage include mental retardation, learning and developmental disabilities, hearing loss, eye movement problems, and death.

Though unconjugated bilirubin may be toxic to brain development in newborns (up to 2-4 weeks of age), it does not pose the same threat to older children and adults. In older children and adults, the “blood-brain barrier” is more developed and prevents bilirubin from gaining access to brain cells. Nevertheless, elevated bilirubin strongly suggests that a medical condition is present that must be evaluated and treated.

Two forms of bilirubin can be measured or estimated by laboratory tests:

- Unconjugated bilirubin (indirect bilirubin) —when heme is released from hemoglobin, it is converted to unconjugated bilirubin. It is carried by proteins to the liver. Small amounts may be present in the blood.

- Conjugated bilirubin (direct bilirubin) —formed in the liver when sugars are attached (conjugated) to bilirubin. It enters the bile and passes from the liver to the small intestines and is eventually eliminated in the stool. Normally, no conjugated bilirubin is present in the blood.

Figure 1. Unconjugated bilirubin and conjugated bilirubin metabolism

As unconjugated bilirubin (indirect bilirubin) is always bound to albumin in serum, it cannot be filtered by the glomeruli (in the absence of glomerular disease). Thus, unconjugated bilirubin is never found in urine even when there is an elevated level of unconjugated bilirubin in circulation. Jaundice that occurs with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia is termed acholuric because the urine is not darkened. Dark urine, however, occurs when there is excretion of an excess of water-soluble, conjugated bilirubin. This is seen in conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and signifies the presence of either liver or biliary disease. Thus the presence of bilirubin in urine will help identify subtle hepatobiliary dysfunction leading to conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, even when the measured concentration of conjugated bilirubin is serum is only slightly elevated. An exception to this rule is when bilirubinuria is not detected in a patient with prolonged cholestasis and marked jaundice. This is due to the formation of delta bilirubin or conjugated bilirubin that is tightly bound to serum albumin. The absence of bilirubinuria in such patients should not cause any difficulty in diagnosing conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, as the patient is clearly jaundiced and serum conjugated bilirubin is markedly elevated in such cases 2.

The rate-limiting step in bilirubin throughput is the liver excretory capacity of conjugated bilirubin. Part of the conjugated bilirubin may accumulate in serum when the hepatic excretion of the conjugated bilirubin is impaired as in prolonged biliary obstruction or intrahepatic cholestasis. This fraction of conjugated bilirubin gets covalently bound to albumin, and is called delta bilirubin or delta fraction or biliprotein. As the delta bilirubin is bound to albumin, its clearance from serum takes about 12-14 days (equivalent to the half-life of albumin) in contrast to the usual 2 to 4 hours (half-life of bilirubin).

The process of bilirubin conjugation alters the physiochemical properties of bilirubin giving it many special properties. Most importantly, it makes the molecule water soluble which allows it to be transported in bile without a protein carrier. Conjugation also increases the size of the molecule. Conjugation prevents bilirubin from passively being reabsorbed by the intestinal mucosa due to its hydrophilicity and large molecular size. Thus, conjugation works to promote the elimination of potentially toxic metabolic waste products. Furthermore, conjugation modestly decreases the affinity of bilirubin for albumin.

Conjugated bilirubin (direct bilirubin) is not reabsorbed from the proximal intestine as mentioned above; in comparison, unconjugated bilirubin is partially reabsorbed across the lipid membrane of the small intestinal epithelium and undergoes enterohepatic circulation. Within the proximal small intestine, there is no additional metabolism of bilirubin, and very little deconjugation takes place. In stark contrast, when the conjugated bilirubin reaches the distal ileum and colon, it is rapidly reduced and deconjugated by colonic flora to a series of molecules termed urobilinogen. The major urobilinoids seen in stool are known as urobilinogen and stercobilinogen, nature and relative proportion of which will depend on the presence and composition of the gut bacterial flora. These substances are colorless but turn orange-yellow after oxidation to urobilin, giving stool its distinctive color.

Red blood cells normally degrade after about 120 days in circulation. As heme is released from hemoglobin, it is converted to unconjugated bilirubin. A small amount (approximately 250 to 350 milligrams) of unconjugated bilirubin is produced daily in a normal, healthy adult. Most (85%) of bilirubin is derived from damaged or degraded red blood cells, with the remaining amount (15%) derived from red blood cell precursors destroyed in the bone marrow and from the catabolism of other heme-containing proteins found in other tissues, primarily the liver and muscles. These proteins include myoglobin, cytochromes, catalase, peroxidase, and tryptophan pyrrolase 3.

Normally, small amounts of unconjugated bilirubin are released into the blood, but virtually no conjugated bilirubin is present. Both forms can be measured or estimated by laboratory tests, and a total bilirubin result (a sum of these) may also be reported.

A number of inherited and acquired diseases affect 1 or more of the steps involved in the production, uptake, storage, metabolism, and excretion of bilirubin. Bilirubinemia is frequently a direct result of these disturbances.

The most commonly occurring form of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia is that seen in newborns and referred to as physiological jaundice.

The increased production of bilirubin, that accompanies the premature breakdown of erythrocytes and ineffective erythropoiesis, results in hyperbilirubinemia in the absence of any liver abnormality.

The rare genetic disorders, Crigler-Najjar syndromes type I and type II, are caused by a low or absent activity of bilirubin UDP-glucuronyl-transferase. In type I, the enzyme activity is totally absent, the excretion rate of bilirubin is greatly reduced and the serum concentration of unconjugated bilirubin is greatly increased. Patients with this disease may die in infancy owing to the development of kernicterus.

In hepatobiliary diseases of various causes, bilirubin uptake, storage, and excretion are impaired to varying degrees. Thus, both conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin are retained and a wide range of abnormal serum concentrations of each form of bilirubin may be observed. Both conjugated and unconjugated bilirubins are increased in hepatitis and space-occupying lesions of the liver; and obstructive lesions such as carcinoma of the head of the pancreas, common bile duct, or ampulla of Vater.

Normal bilirubin results

It is normal to have some bilirubin in the blood. A normal level is:

- Direct bilirubin or conjugated bilirubin: less than 0.3 mg/dL (less than 5.1 µmol/L)

- Total serum bilirubin: 0.1 to 1.2 mg/dL (1.71 to 20.5 µmol/L)

Normal value ranges may vary slightly among different laboratories. Some labs use different measurements or may test different samples. Talk to your health care provider about the meaning of your specific test results.

Bilirubin concentrations tend to be slightly higher in males than females. African Americans routinely show lower bilirubin concentrations than non-African Americans. Strenuous exercise may increase bilirubin levels.

Usually, a chemical test is used to first measure the total bilirubin level (unconjugated plus conjugated bilirubin). If the total bilirubin level is increased, the laboratory can use a second chemical test to detect water-soluble forms of bilirubin, called “direct” bilirubin. The direct bilirubin test provides an estimate of the amount of conjugated bilirubin present. Subtracting direct bilirubin level from the total bilirubin level helps estimate the “indirect” level of unconjugated bilirubin. The pattern of bilirubin test results can give the healthcare provider information regarding the condition that may be present.

Elevated bilirubin (hyperbilirubinemia)

If the bilirubin level increases in the blood, a person may appear jaundiced, with a yellowing of the skin and/or whites of the eyes. The pattern of bilirubin test results can give the health care practitioner information regarding the condition that may be present. For example, unconjugated bilirubin (indirect bilirubin) may be increased when there is an unusual amount of red blood cell destruction (hemolysis) or when the liver is unable to process bilirubin (i.e., with liver diseases such as cirrhosis or inherited problems). Conversely, conjugated bilirubin (direct bilirubin) can increase when the liver is able to process bilirubin but is not able to pass the conjugated bilirubin to the bile for removal; when this happens, the cause is often acute hepatitis or blockage of the bile ducts.

Increased total and unconjugated bilirubin levels are relatively common in newborns in the first few days after birth. This finding is called “physiologic jaundice of the newborn” and occurs because the newborn’s liver is not mature enough to process bilirubin yet. Usually, physiologic jaundice of the newborn resolves itself within a few days. However, in hemolytic disease of the newborn, red blood cells may be destroyed because of blood incompatibilities between the baby and the mother; in these cases, treatment may be required because high levels of unconjugated bilirubin can damage the newborn’s brain. The level of bilirubinemia that results in kernicterus in a given infant is unknown. In preterm infants, the risk of a handicap increases by 30% for each 2.9 mg/dL increase of maximal total bilirubin concentration. While central nervous system damage is rare when total serum bilirubin is less than 20 mg/dL, premature infants may be affected at lower levels. The decision to institute therapy is based on a number of factors including total serum bilirubin, age, clinical history, physical examination, and coexisting conditions. Phototherapy typically is discontinued when total serum bilirubin level reaches 14 to 15 mg/dL.

A rare (about 1 in 10,000 births) but life-threatening congenital condition called biliary atresia can cause increased total and conjugated bilirubin levels in newborns. This condition must be quickly detected and treated, usually with surgery, to prevent serious liver damage that may require liver transplantation within the first few years of life. Some children may require liver transplantation despite early surgical treatment.

Adults and children with hyperbilirubinemia

Increased total bilirubin that is mainly unconjugated bilirubin (indirect bilirubin) may be a result of:

- Hemolytic or pernicious anemia

- Transfusion reaction

- Scarring of the liver (cirrhosis)

- A relatively common inherited condition called Gilbert syndrome, due to low levels of the enzyme that produces conjugated bilirubin

If conjugated bilirubin (direct bilirubin) is elevated more than unconjugated bilirubin (indirect bilirubin), there typically is a problem associated with decreased elimination of bilirubin by the liver cells. Some conditions that may cause this include:

- Viral hepatitis

- Drug reactions

- Alcoholic liver disease

Conjugated bilirubin (direct bilirubin) is also elevated more than unconjugated bilirubin (indirect bilirubin) when there is blockage of the bile ducts. This may occur, for example, with:

- Gallstones present in the bile ducts

- Cancer of the pancreas or gallbladder

- Scarring of the bile ducts

Rare inherited disorders that cause abnormal bilirubin metabolism such as Rotor, Dubin-Johnson, and Crigler-Najjar syndromes, may also cause increased levels of bilirubin. The Gilbert syndrome, Dubin-Johnson syndrome and Rotor syndrome are usually mild, chronic conditions that can be aggravated under certain conditions but in general cause no significant health problems. For example, Gilbert syndrome is very common; about 1 in every 6 people has this genetic abnormality, but usually people with Gilbert syndrome do not have elevated bilirubin. Crigler-Najjar syndrome is the most serious inherited condition listed; this disorder is relatively rare, and some people with it may die.

The drug atazanavir increases unconjugated bilirubin (indirect bilirubin). Drugs that can decrease total bilirubin include barbiturates, caffeine, penicillin, and high doses of salicylates.

Newborns with hyperbilirubinemia

An elevated bilirubin level in a newborn may be temporary and resolve itself within a few days to two weeks. However, if the bilirubin level is above a critical threshold or increases rapidly, an investigation of the cause is needed so appropriate treatment can be initiated. Increased bilirubin concentrations may result from the accelerated breakdown of red blood cells due to:

- Blood type incompatibility between the mother and her newborn, a blood disorder called erythroblastosis fetalis or hemolytic disease of the newborn

- Certain congenital infections

- Lack of oxygen (hypoxia)

- Diseases that can affect the liver

In most of these conditions, only unconjugated bilirubin (indirect bilirubin) is increased. An elevated conjugated bilirubin (direct bilirubin) is seen in the rare conditions of biliary atresia and neonatal hepatitis. Biliary atresia requires surgical intervention to prevent liver damage.

Bilirubin high treatment

Treatment depends on the cause of the jaundice or hyperbilirubinemia. In newborns, phototherapy (special light therapy), blood exchange transfusion, and/or certain drugs may be used to reduce the bilirubin level. In Gilbert, Rotor, and Dubin-Johnson syndromes, no treatment is usually necessary. Crigler-Najjar syndrome may respond to certain enzyme drug therapy or may require a liver transplant. Jaundice caused by an obstruction is often resolved by surgery. Jaundice due to cirrhosis is a result of long-term liver damage and does not respond well to any type of therapy other than liver transplantation.

References- Kalakonda A, John S. Physiology, Bilirubin. [Updated 2019 May 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470290

- Patel SP, Vasavda C, Ho B, Meixiong J, Dong X, Kwatra SG. Cholestatic pruritus: Emerging mechanisms and therapeutics. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019 Apr 1

- Ngashangva L, Bachu V, Goswami P. Development of new methods for determination of bilirubin. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2019 Jan 05;162:272-285.