Bleeding in the upper gastrointestinal tract

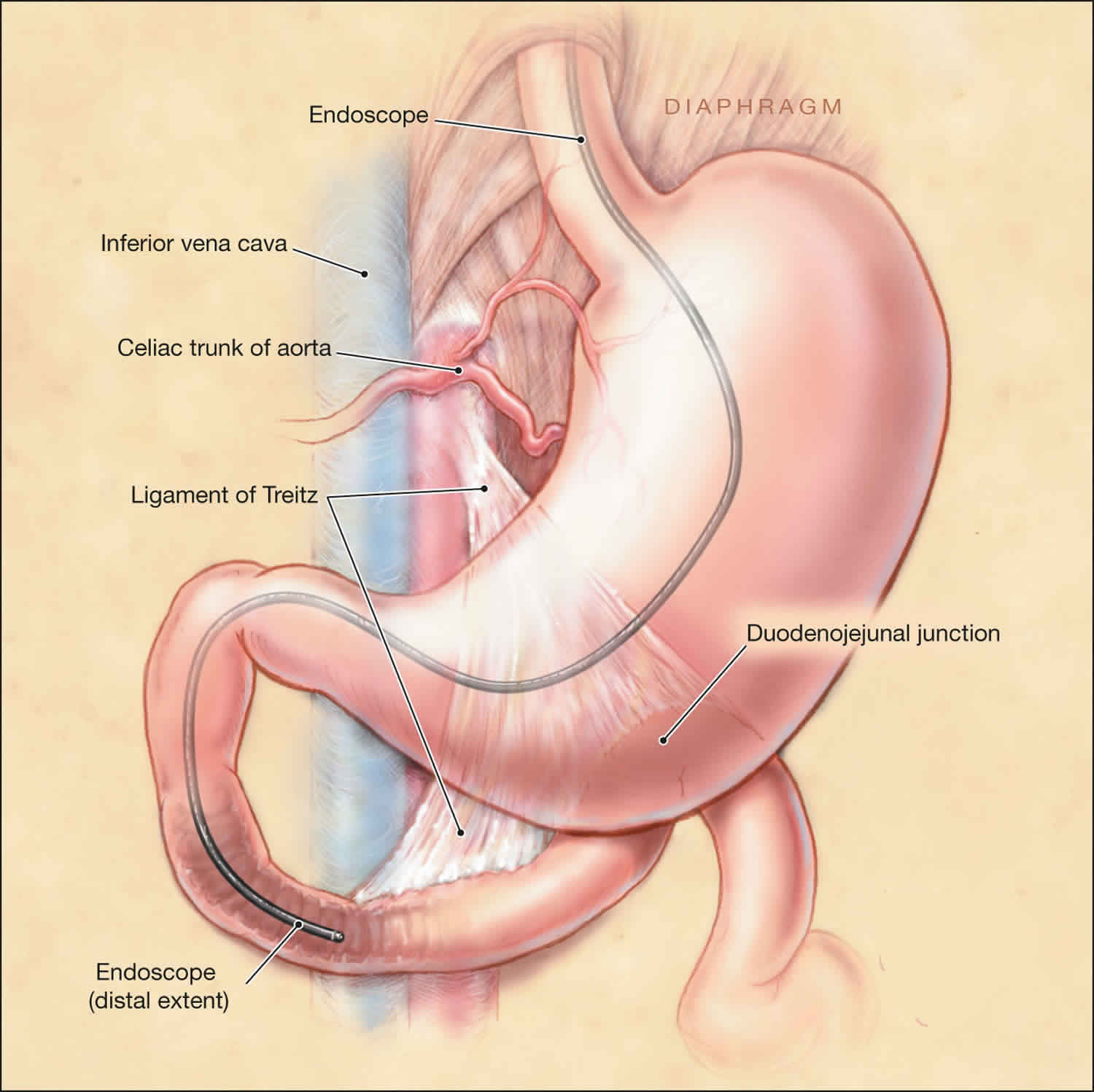

Upper GI bleeding or upper gastrointestinal bleeding is classified as any blood loss from a gastrointestinal source above the ligament of Treitz, this includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, and small intestine 1. Upper GI bleeding can manifest as hematemesis (bright red emesis or coffee-ground emesis), hematochezia, or melena. Patients can also present with symptoms secondary to blood loss, such as syncopal episodes, fatigue, and weakness. Upper GI bleeding can be acute, occult, or obscure 2. Upper GI bleeding is a common problem with an annual incidence of approximately 80 to 150 per 100,000 population, with estimated mortality rates between 2% to 15%.

Bleeding in upper digestive tract accounts for 75% of all acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding cases. Its annual incidence is approximately 80 to 150 per 100,000 population. Patients on long-term, low-dose aspirin have a higher risk of overt upper GI tract bleeding compared to placebo. When aspirin is combined with P2Y12 inhibitors such as clopidogrel, there is a two-fold to three-fold increase in the number of upper GI tract bleeding cases. When a patient requires triple therapy (i.e., aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitor and vitamin K antagonist), the risk of upper GI tract bleeding is even higher 3.

Management of the patient presenting with upper GI tract bleeding should always follow a step-wise approach. The first step is to assess the hemodynamic status and initiate resuscitative efforts as needed (including fluids and blood transfusions). Patients should be risk stratified based on their initial presentation, hemodynamic status, comorbidities, age, and initial laboratory tests. There are several scoring systems available, with the most commonly used being the Rockall and Blatchford scores. Upper endoscopy should be offered within 24 hours to help diagnose the source of bleeding and help further guide management if needed.

If a bleeding ulcer is found to be the culprit lesion, efforts should be taken to prevent recurrence of bleeding. If the patient is found to have H. pylori, eradication should be a target. If nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were likely the cause of the bleeding, they should be stopped, and if absolutely needed, alternative agents such as COX-2-selective NSAID plus a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) should be used. Patients with established cardiovascular disease who require aspirin or other antiplatelet agents should be on proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy and generally can have antiplatelet therapy reinstituted after bleeding ceases (ideally within 1 to 3 days and certainly within 7 days).

The natural history of patients who are treated with endoscopic therapy is that 80% to 90% of patients will have permanent control of their bleeding. However, 10% to 20% will rebleed. Patients who rebleed should have a second endoscopic procedure attempted. If bleeding persists despite endoscopic intervention or source of bleeding can not be identified, other modalities such as angiography or surgery should be considered 4.

Causes of upper GI bleeding

From the possible causes of upper GI tract bleeding, peptic ulcer disease accounts for 40% to 50% of the cases. Of those, the majority is secondary to duodenal ulcers (30%). Peptic ulcer disease can be associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), Helicobacter pylori, and stress-related mucosal disease 5.

Aside from peptic ulcer disease, erosive esophagitis accounts for 11%, duodenitis for 10%, varices 5% to 30% (depending if the population studied have a chronic liver disease), Mallory-Weiss tear 5% to 15% and vascular malformations for 5%.

Upper GI bleed signs and symptoms

Acute upper GI tract bleeding symptoms may include 6:

- Hematemesis (vomiting blood): 40%-50%

- Melena: 70%-80%

- Hematochezia: 15%-20%

- Either hematochezia or melena: 90%-98%

- Syncope: 14.4%

- Presyncope: 43.2%

- Symptoms 30 days prior to admission: No percentage available

- Dyspepsia: 18%

- Epigastric pain: 41%

- Heartburn: 21%

- Diffuse abdominal pain: 10%

- Dysphagia: 5%

- Weight loss: 12%

- Jaundice: 5.2%

The clinical presentation can vary but should be well-characterized. Vomiting blood (hematemesis) is the overt bleeding with vomiting of fresh blood or clots. Melena refers to dark and tarry-appearing stools with a distinctive smell. The term “coffee-grounds” describes gastric aspirate or vomitus that contains dark specks of old blood. Hematochezia is the passage of fresh blood per rectum. The latter is usually a reflection of lower gastrointestinal bleeding but may be seen in patients with brisk upper GI tract bleeding.

Patients may also present with syncope or orthostatic hypotension if bleeding is severe enough to cause hemodynamic instability.

In a comprehensive exam, search for evidence of chronic liver diseases such as palmar erythema, spider angiomas, gynecomastia, jaundice, and ascites. These features may give clues to the etiology of the bleeding (i.e., variceal bleeding).

Upper GI bleed diagnosis

To diagnose gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, a doctor will first find the site of the bleeding based on your medical history—including what medicines you are taking—and family history, a physical exam, and diagnostic tests.

Physical exam

During a physical exam, a doctor most often

- examines your body

- listens to sounds in your abdomen using a stethoscope

- taps on specific areas of your body

Diagnostic tests

Depending on your symptoms, your doctor will order one or more diagnostic tests to confirm whether you have GI bleeding and, if so, to help find the source of the bleeding.

Initial laboratory work must include a complete blood cell count (CBC) to look for current levels of hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelets. A low MCV can point towards chronic blood loss and iron deficiency anemia. Chemistry should also be evaluated. Elevated BUN or elevated BUN/Creatinine can also be indicative of upper GI tract bleeding. Coagulation panel should also be checked 7.

There are few scoring systems designed to predict which patients will likely need intervention and also to predict rebleeding and mortality. The Rockall score was designed to predict rebleeding and mortality and includes age, comorbidities, the presence of shock, and endoscopic stigmata. A pre-endoscopic Rockall is also available and can be used to stratify patient’s risk for rebleeding and mortality even before the endoscopic evaluation. When the Rockall score is used, patients with two or fewer points are considered low risk and have a 4.3% probability of rebleeding and 0.1% mortality. In contrast, patients with a score of six or more have a rebleeding rate of 15% and mortality of 39%.

Another scoring system that is traditionally used in upper GI tract bleeding is the Blatchford Score. This scoring system was designed to predict the need for intervention. It includes hemoglobin levels, blood pressure, presentation of syncope, melena, liver disease, and heart failure. A score of six or higher is associated with a greater than 50% risk of needing an intervention.

If the patient is suspected of having upper GI tract bleeding, endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy) must be performed to identify the cause and potentially treat the source of bleeding. Multiple studies have tried to identify the best timing to perform endoscopy. Until now, there is no evidence that emergent esophagogastroduodenoscopy is superior to routine EGD (done in 24 to 48 hours). The American College of Gastroenterology continues to recommend that all patients with upper GI tract bleeding should undergo endoscopy within 24 hours of admission, following resuscitative efforts to optimize hemodynamic parameters and other medical problems. Per American College of Gastroenterology recommendations, endoscopy within 12 hours should be considered for all patients with higher risk clinical features (e.g., tachycardia, hypotension, bloody emesis or nasogastric aspirate in the hospital) to potentially improve clinical outcomes 8.

Upper GI bleed treatment

Patients must have a minimum of two large-bore peripheral access catheters (at least 18-gauge). Intravenous fluids should be administered to maintain adequate blood pressure and hemodynamic stability. If patients are not able to protect their airways or have ongoing severe hematemesis, elective endotracheal intubation is advised.

Blood transfusions should be given to target a hematocrit above 20%, with a hematocrit above 30% targeted in high-risk patients, such as the elderly and patients with coronary artery disease. There is no evidence that higher targets for hematocrit goals should be sought as that higher targets can even be deleterious 9.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are used to treat patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleed. The use of antacids has been shown to alter the natural history of patients with acute upper GI bleeding. Patients with significant bleeding should be treated with an 80-mg bolus of proton pump inhibitor followed by a continuous infusion. The typical duration is 72 hours for patients with high-risk lesions visualized on esophagogastroduodenoscopy. If endoscopy was normal or only revealed low-risk lesion, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) infusion can be discontinued and patient switch to a daily twice a day infusion or even to oral proton pump inhibitors.

Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, is a medication used when variceal bleeding is suspected. It is given as an intravenous bolus of 20 mcg to 50 mcg, followed by a continuous infusion at a rate of 25 mcg to 50 mcg per hour. Its use is not recommended in patients with acute nonvariceal upper GI bleeding, but it can be used as adjunctive therapy in some cases. Its role is limited to settings in which endoscopy is unavailable or as a means to help stabilize patients before definitive therapy can be performed.

Endoscopic intervention might be warranted depending on the findings during the upper endoscopy. If a patient has an ulcer with a clean base, no intervention is needed. However, if a bleeding vessel is visualized or there is stigmata of recent bleeding, therapeutic options might include thermal coagulation to achieve hemostasis, local injection of epinephrine or use of clips. A combination of these methods might be needed based on the severity of the lesions.

Upper GI bleeding prognosis

Recurrence of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is common. In a study to evaluate national 30-day re-admissions after upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in US patients, of 82,290 patients admitted for upper GI tract bleeding, the all-cause 30-day readmission rate was 14.6% (vs 14.4% for lower gastrointestinal bleeding) 10. The most common causes of upper GI tract bleeding were GI (33.9%), cardiac (13.3%), infectious (10.4%), and respiratory (7.8%). Significant predictors of 30-day readmission were metastatic disease, discharge against medical advice, and hospital stay for longer than 3 days 10.

Age older than 60 years is an independent marker for a poor outcome in upper GI tract bleeding 11, with the mortality rate ranging from 12% to 25% in this group of patients.

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy grouped patients with upper GI tract bleeding according to age and correlated age category to the risk of mortality. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy found a mortality of 3.3% for patients aged 21-31 years, 10.1% for those aged 41-50 years, and 14.4% for those aged 71-80 years 11.

The following risk factors are associated with an increased mortality, recurrent bleeding, the need for endoscopic hemostasis, or surgery 12:

- Age older than 60 years

- Severe comorbidity

- Active bleeding (eg, witnessed hematemesis, red blood per nasogastric tube, fresh blood per rectum)

- Hypotension

- Red blood cell transfusion greater than or equal to 6 units

- Inpatient at time of bleed

- Severe coagulopathy

Patients who present in hemorrhagic shock have a mortality rate of up to 30%.

References- Antunes C, Copelin II EL. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. [Updated 2019 Apr 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470300

- Kamboj AK, Hoversten P, Leggett CL. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Etiologies and Management. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019 Apr;94(4):697-703.

- Sehested TSG, Carlson N, Hansen PW, Gerds TA, Charlot MG, Torp-Pedersen C, Køber L, Gislason GH, Hlatky MA, Fosbøl EL. Reduced risk of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with proton pump inhibitor therapy in patients treated with dual antiplatelet therapy after myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2019 Mar 09

- Hajiagha Mohammadi AA, Reza Azizi M. Prognostic factors in patients with active non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2019 Mar;20(1):23-27.

- Stanley AJ, Laine L. Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ. 2019 Mar 25;364:l536.

- Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding (UGIB) Clinical Presentation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/187857-clinical

- Mocker L, Hildenbrand R, Oyama T, Sido B, Yahagi N, Dumoulin FL. Implementation of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early upper gastrointestinal tract cancer after primary experience in colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endosc Int Open. 2019 Apr;7(4):E446-E451.

- Jung K, Moon W. Role of endoscopy in acute gastrointestinal bleeding in real clinical practice: An evidence-based review. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2019 Feb 16;11(2):68-83.

- Sung JJ, Chiu PW, Chan FKL, Lau JY, Goh KL, Ho LH, Jung HY, Sollano JD, Gotoda T, Reddy N, Singh R, Sugano K, Wu KC, Wu CY, Bjorkman DJ, Jensen DM, Kuipers EJ, Lanas A. Asia-Pacific working group consensus on non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: an update 2018. Gut. 2018 Oct;67(10):1757-1768.

- Robertson M, Majumdar A, Boyapati R, et al. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding: comparison of the AIMS65 score with the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jun. 83(6):1151-60.

- Peter DJ, Dougherty JM. Evaluation of the patient with gastrointestinal bleeding: an evidence based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999 Feb. 17(1):239-61, x.

- Elmunzer BJ, Young SD, Inadomi JM, Schoenfeld P, Laine L. Systematic review of the predictors of recurrent hemorrhage after endoscopic hemostatic therapy for bleeding peptic ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Oct. 103(10):2625-32; quiz 2633.