Urethral cancer

Urethral cancer is a rare cancer that forms in tissues of the urethra (the tube through which urine empties the bladder and leaves the body). The urethra is the tube that carries urine from the bladder to outside the body. In women, the urethra is about 1½ inches long and is just above the vagina. In men, the urethra is about 8 inches long, and goes through the prostate gland and the penis to the outside of the body. In men, the urethra also carries semen. Urethral cancer is more common in men than in women. Urethral cancer can metastasize (spread) quickly to tissues around the urethra and has often spread to nearby lymph nodes by the time it is diagnosed.

The annual incidence rate for urethral cancer in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database during the period from 1973 to 2002 in the United States for men was 4.3 per million and for women was 1.5 per million, with downward trends over the three decades 1. The incidence was twice as high in African Americans as in whites (5 million vs. 2.5 per million). Urethral cancers appear to be associated with infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly HPV16, a strain of HPV known to be causative for cervical cancer 2.

In an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data from 1973 to 2002, the most common histologic types of urethral cancer were 1:

- Transitional cell (55%). Transitional cell carcinoma forms in the area near the urethral opening in women, and in the part of the urethra that goes through the prostate gland in men.

- Squamous cell (21.5%). Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of urethral cancer. It forms in the thin, flat cells in the part of the urethra near the bladder in women, and in the lining of the urethra in the penis in men.

- Adenocarcinoma (16.4%). Adenocarcinoma forms in the glands that are around the urethra in both men and women.

Other cell types, such as melanoma, were extremely rare 1.

The female urethra is lined by transitional cell mucosa proximally and stratified squamous cells distally. Therefore, transitional cell carcinoma is most common in the proximal urethra and squamous cell carcinoma predominates in the distal urethra. Adenocarcinoma may occur in both locations and arises from metaplasia of the numerous periurethral glands.

The male urethra is lined by transitional cells in its prostatic and membranous portion and stratified columnar epithelium to stratified squamous epithelium in the bulbous and penile portions. The submucosa of the urethra contains numerous glands. Therefore, urethral cancer in the male can manifest the histological characteristics of transitional cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or adenocarcinoma.

Except for the prostatic urethra, where transitional cell carcinoma is most common, squamous cell carcinoma is the predominant histology of urethral neoplasms. Since transitional cell carcinoma of the prostatic urethra may be associated with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and/or transitional cell carcinoma arising in prostatic ducts, it is often treated similarly to these primaries and should be separated from the more distal carcinomas of the urethra.

The histology of the primary urethral cancer is of less importance in estimating response to therapy and survival 3. Endoscopic examination, urethrography, and magnetic resonance imaging are useful in determining the local extent of the tumor 4.

Urethral cancer key points

- Urethral cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the urethra.

- There are different types of urethral cancer that begin in cells that line the urethra.

- A history of bladder cancer can affect the risk of urethral cancer.

- Signs of urethral cancer include bleeding or trouble with urination.

- Tests that examine the urethra and bladder are used to detect (find) and diagnose urethral cancer.

- Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

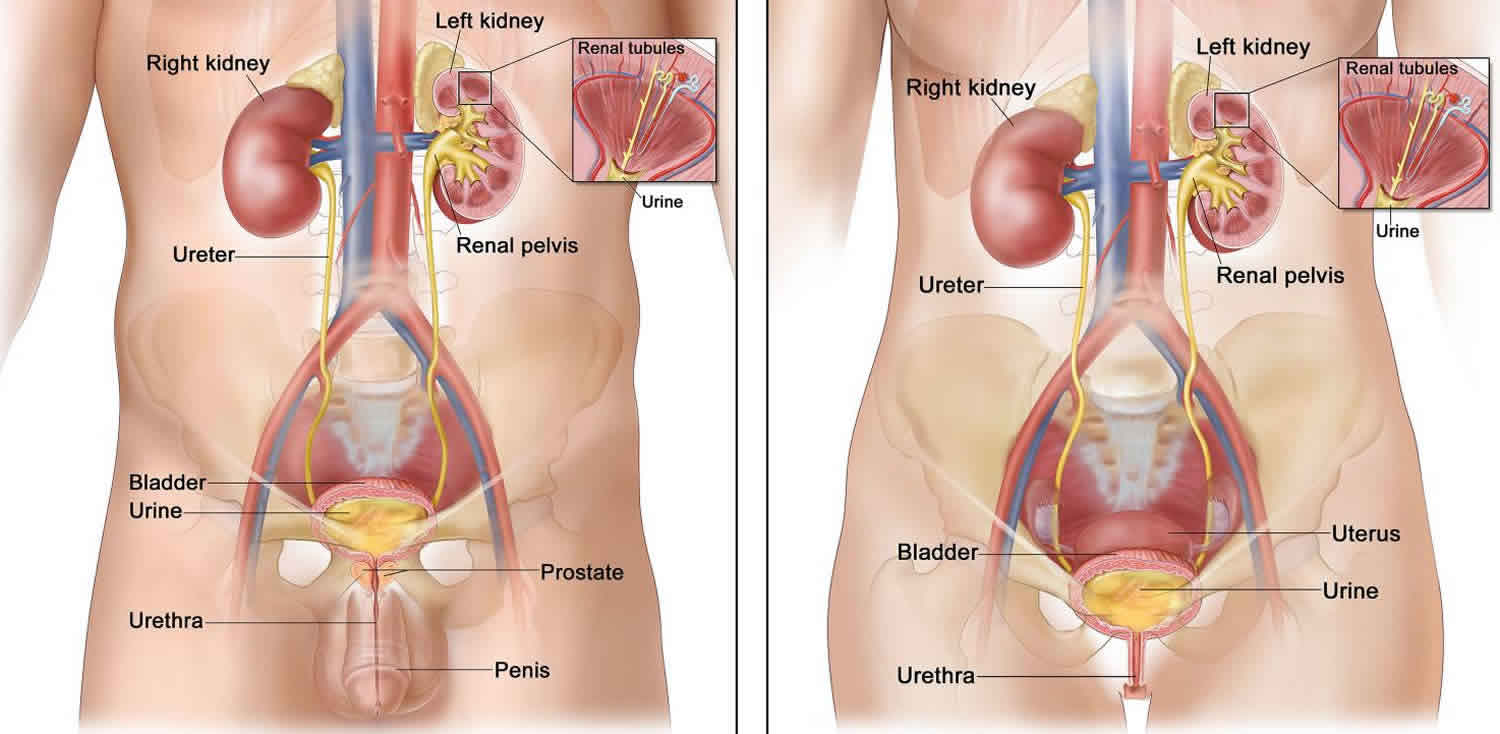

Urethra anatomy

The female urethra is largely contained within the anterior vaginal wall. In adults, it is about 4 cm in length.

The male urethra, which averages about 20 cm in length, is divided into distal and proximal portions. The distal urethra, which extends distally to proximally from the tip of the penis to just before the prostate, includes the meatus, the fossa navicularis, the penile or pendulous urethra, and the bulbar urethra. The proximal urethra, which extends from the bulbar urethra to the bladder neck, includes distally to proximally the membranous urethra and the prostatic urethra.

Footnote: Anatomy of the male urinary system (left panel) and female urinary system (right panel) showing the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. Urine is made in the renal tubules and collects in the renal pelvis of each kidney. The urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the bladder. The urine is stored in the bladder until it leaves the body through the urethra.

Urethral cancer causes

The cause of urethral cancer is obscure. Although cigarette smoking, exposure to aromatic amines, and analgesic abuse are associated with transitional-cell carcinoma of the bladder, no such correlation has been established with urethral carcinoma. However, patients with a history of bladder cancer are at an increased risk of urethral cancer.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) has been associated with nearly one-third of cases of urethral cancer in some studies. In men, the risk factors for primary urethral cancer include urethral stricture (25–76%), sexually transmitted diseases (24–50%), and trauma (7%). In females, chronic irritation (including HPV infection), diverticula, sexual activity, and childbirth are associated with the development of primary urethral cancer 5.

Chronic inflammation as an etiology of urethral cancer is highly controversial. One study found that 88% of male patients with urethral cancer had a history of stricture; another study found the correlation in only 16% of patients. This is further supported by the high prevalence of primary urethral cancer in the bulbomembranous urethra, which is also the most common location of urethral strictures.

In rare instances, arsenic ingestion has been associated with an increased risk of primary urethral cancer 6.

Risk factors for urethral cancer

Anything that increases your chance of getting a disease is called a risk factor. Having a risk factor does not mean that you will get cancer; not having risk factors doesn’t mean that you will not get cancer. Talk with your doctor if you think you may be at risk. Risk factors for urethral cancer include the following:

- Having a history of bladder cancer.

- Having conditions that cause chronic inflammation in the urethra, including:

- Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including human papillomavirus (HPV), especially HPV type 16.

- Frequent urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Urethral cancer signs and symptoms

These and other signs and symptoms may be caused by urethral cancer or by other conditions. There may be no signs or symptoms in the early stages of urethral cancer. Check with your doctor if you have any of the following:

- Trouble starting the flow of urine.

- Weak or interrupted (“stop-and-go”) flow of urine.

- Frequent urination, especially at night.

- Incontinence.

- Discharge from the urethra.

- Bleeding from the urethra or blood in the urine.

- A lump or thickness in the perineum or penis.

- A painless lump or swelling in the groin.

Urethral cancer diagnosis

Tests that examine the urethra and bladder are used to detect (find) and diagnose urethral cancer.

The following tests and procedures may be used:

- Physical exam and history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- Pelvic exam: An exam of the vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and rectum. A speculum is inserted into the vagina and the doctor or nurse looks at the vagina and cervix for signs of disease. The doctor or nurse also inserts one or two lubricated, gloved fingers of one hand into the vagina and places the other hand over the lower abdomen to feel the size, shape, and position of the uterus and ovaries. The doctor or nurse also inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the rectum to feel for lumps or abnormal areas.

- Digital rectal exam: An exam of the rectum. The doctor or nurse inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the lower part of the rectum to feel for lumps or anything else that seems unusual.

- Urine cytology: A laboratory test in which a sample of urine is checked under a microscope for abnormal cells.

- Urinalysis: A test to check the color of urine and its contents, such as sugar, protein, blood, and white blood cells. If white blood cells (a sign of infection) are found, a urine culture is usually done to find out what type of infection it is.

- Blood chemistry studies: A procedure in which a blood sample is checked to measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual (higher or lower than normal) amount of a substance can be a sign of disease.

- Complete blood count (CBC): A procedure in which a sample of blood is drawn and checked for the following:

- The number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- The amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells.

- The portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells.

- CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the pelvis and abdomen, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

- Ureteroscopy: A procedure to look inside the ureter and renal pelvis to check for abnormal areas. A ureteroscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. The ureteroscope is inserted through the urethra into the bladder, ureter, and renal pelvis. A tool may be inserted through the ureteroscope to take tissue samples to be checked under a microscope for signs of disease.

- Biopsy: The removal of cell or tissue samples from the urethra, bladder, and, sometimes, the prostate gland. The samples are viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for signs of cancer.

Urethral cancer staging

After urethral cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread within the urethra or to other parts of the body.

The process used to find out if cancer has spread within the urethra or to other parts of the body is called staging. The information gathered from the staging process determines the stage of the disease. It is important to know the stage in order to plan treatment.

The following procedures may be used in the staging process:

- Chest x-ray: An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

- CT scan (CAT scan) of the pelvis and abdomen: A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of the pelvis and abdomen, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of the urethra, nearby lymph nodes, and other soft tissue and bones in the pelvis. A substance called gadolinium is injected into the patient through a vein. The gadolinium collects around the cancer cells so they show up brighter in the picture. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

- Urethrography: A series of x-rays of the urethra. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body. A dye is injected through the urethra into the bladder. The dye coats the bladder and urethra and x-rays are taken to see if the urethra is blocked and if cancer has spread to nearby tissue.

Urethral cancer is staged and treated based on the part of the urethra that is affected and how deeply the tumor has spread into tissue around the urethra. Urethral cancer can be described as distal or proximal.

Urethral cancer stage definitions by depth of invasion

- Stage 0 (Tis, Ta): Limited to mucosa.

- Stage A (T1): Submucosal invasion.

- Stage B (T2): Infiltrating periurethral muscle or corpus spongiosum.

- Stage C (T3): Infiltration beyond periurethral tissue.

- Female: Vagina, labia, muscle.

- Male: Corpus cavernosum, muscle.

- Stage D1 (N+): Regional nodes; pelvic and inguinal.

- Stage D2 (N+, M+): Distant nodes; visceral metastases.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has designated staging by TNM classification to define urethral cancer 7.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) use 3 factors to stage (classify) urethral cancer:

- The extent (size) of the tumor (T): Has the cancer spread outside the ovary or fallopian tube? Has the cancer reached nearby pelvic organs like the uterus or bladder?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to the lymph nodes in the pelvis or around the aorta (the main artery that runs from the heart down along the back of the abdomen and pelvis)? Also called para-aortic lymph nodes.

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to fluid around the lungs (malignant pleural effusion) or to distant organs such as the liver or bones?

Primary Tumor (T) (Male and Female)

- TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed.

- T0 No evidence of primary tumor.

- Ta Noninvasive papillary, polypoid, or verrucous carcinoma.

- Tis Carcinoma in situ.

- T1 Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue.

- T2 Tumor invades any of the following: corpus spongiosum, prostate, periurethral muscle.

- T3 Tumor invades any of the following: corpus cavernosum, beyond prostatic capsule, anterior vagina, bladder neck.

- T4 Tumor invades other adjacent organs.

Urothelial (Transitional Cell) Carcinoma of the Prostate

- Tis pu Carcinoma in situ, involvement of the prostatic urethra.

- Tis pd Carcinoma in situ, involvement of the prostatic ducts.

- T1 Tumor invades urethral subepithelial connective tissue.

- T2 Tumor invades any of the following: prostatic stroma, corpus spongiosum, periurethral muscle.

- T3 Tumor invades any of the following: corpus cavernosum, beyond prostatic capsule, bladder neck (extraprostatic extension).

- T4 Tumor invades other adjacent organs (invasion of the bladder).

Regional Lymph Nodes

- NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed.

- N0 No regional lymph node metastasis.

- N1 Metastasis in a single lymph node 2 cm or less in greatest dimension.

- N2 Metastasis in a single node more than 2 cm in greatest dimension, or in multiple nodes.

Distant Metastasisa

- M0 No distant metastasis.

- M1 Distant metastasis

Table 1. Anatomic Stage or Prognostic Groups

| Stage | T | N | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0a | Ta | N0 | M0 |

| 0is | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| Tis pu | N0 | M0 | |

| Tis pd | N0 | M0 | |

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| III | T1 | N1 | M0 |

| T2 | N1 | M0 | |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | |

| IV | T4 | N0 | M0 |

| T4 | N1 | M0 | |

| Any T | N2 | M0 | |

| Any T | Any N | M1 |

Distal urethral cancer

These lesions are often superficial.

- Female: Lesions of the distal third of the urethra.

- Male: Anterior, or penile, portion of the urethra, including the meatus and pendulous urethra.

In distal urethral cancer, the cancer usually has not spread deeply into the tissue. In women, the part of the urethra that is closest to the outside of the body (about ½ inch) is affected. In men, the part of the urethra that is in the penis is affected.

Proximal urethral cancer

These lesions are often deeply invasive.

- Female: Lesions not clearly limited to the distal third of the urethra.

- Male: Bulbomembranous and prostatic urethra.

Proximal urethral cancer affects the part of the urethra that is not the distal urethra. In women and men, proximal urethral cancer usually has spread deeply into tissue.

Urethral cancer associated with invasive bladder cancer

In men, cancer that forms in the proximal urethra (the part of the urethra that passes through the prostate to the bladder) may occur at the same time as cancer of the bladder and/or prostate. Sometimes this occurs at diagnosis and sometimes it occurs later.

Approximately 5% to 10% of men with cystectomy for bladder cancer may have or may develop urethral cancer distal to the urogenital diaphragm 8.

Recurrent urethral cancer

Recurrent urethral cancer is cancer that has recurred (come back) after it has been treated. The cancer may come back in the urethra or in other parts of the body.

Treatment options:

- Locally recurrent urethral cancer after radiation therapy should be treated by surgical excision, if feasible.

- Locally recurrent urethral cancer after surgery alone should be considered for combination radiation and wider surgical resection.

- Metastatic urethral cancer should be considered for clinical trials using chemotherapy. Transitional cell cancer of the urethra may respond favorably to the same chemotherapy regimens employed for advanced transitional cell cancer of the bladder 8.

Urethral cancer treatment

There are different types of treatment for patients with urethral cancer. Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment. Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Surgery is the mainstay of therapy for urethral cancers in both women and men. The surgical approach depends on tumor stage and anatomic location, and tumor grade plays a less important role in treatment decisions 9. Although the traditional recommendation has been to achieve a 2-cm tumor-free margin, the optimal surgical margin has not been rigorously studied and is not well defined. The role of lymph node dissection is not clear in the absence of clinical involvement, and the role of prophylactic dissection is controversial 9. Radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy may be added in some cases in patients with extensive disease or in an attempt at organ preservation; but there are no clear guidelines for patient selection, and the low level of evidence precludes confident conclusions about their incremental benefit 10.

Ablative techniques, such as transurethral resection, electroresection and fulguration, or laser vaporization-coagulation, are used to preserve organ function in cases of superficial anterior tumors, although the supporting literature is scant 9.

Four types of standard treatment are used:

Surgery

Surgery to remove the cancer is the most common treatment for cancer of the urethra. One of the following types of surgery may be done:

- Open excision: Removal of the cancer by surgery.

- Transurethral resection (TUR): Surgery to remove the cancer using a special tool inserted into the urethra.

- Electroresection with fulguration: Surgery to remove the cancer by electric current. A lighted tool with a small wire loop on the end is used to remove the cancer or to burn the tumor away with high-energy electricity.

- Laser surgery: A surgical procedure that uses a laser beam (a narrow beam of intense light) as a knife to make bloodless cuts in tissue or to remove or destroy tissue.

- Lymph node dissection: Lymph nodes in the pelvis and groin may be removed.

- Cystourethrectomy: Surgery to remove the bladder and the urethra.

- Cystoprostatectomy: Surgery to remove the bladder and the prostate.

- Anterior exenteration: Surgery to remove the urethra, the bladder, and the vagina. Plastic surgery may be done to rebuild the vagina.

- Partial penectomy: Surgery to remove the part of the penis surrounding the urethra where cancer has spread. Plastic surgery may be done to rebuild the penis.

- Radical penectomy: Surgery to remove the entire penis. Plastic surgery may be done to rebuild the penis.

If the urethra is removed, the surgeon will make a new way for the urine to pass from the body. This is called urinary diversion. If the bladder is removed, the surgeon will make a new way for urine to be stored and passed from the body. The surgeon may use part of the small intestine to make a tube that passes urine through an opening (stoma). This is called an ostomy or urostomy. If a patient has an ostomy, a disposable bag to collect urine is worn under clothing. The surgeon may also use part of the small intestine to make a new storage pouch (continent reservoir) inside the body where the urine can collect. A tube (catheter) is then used to drain the urine through a stoma.

After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen at the time of the surgery, some patients may be given chemotherapy or radiation therapy after surgery to kill any cancer cells that are left. Treatment given after the surgery, to lower the risk that the cancer will come back, is called adjuvant therapy.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. There are two types of radiation therapy:

- External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer.

- Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer.

The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the type of cancer and where the cancer formed in the urethra. External and internal radiation therapy are used to treat urethral cancer.

Radiation therapy with external beam, brachytherapy, or a combination is sometimes used for the primary therapy of early-stage proximal urethral cancers, particularly in women. Brachytherapy may be delivered with low-dose-rate iridium Ir 192 sources using a template or urethral catheter. Definitive radiation is also sometimes used for advanced-stage tumors, but because monotherapy of large tumors has shown poor tumor control, it is more frequently incorporated into combined modality therapy after surgery or with chemotherapy 11. There are no head-to-head comparisons of these various approaches, and patient selection may explain differences in outcomes among the regimens.

The most commonly used tumor doses are in the range of 60 Gy to 70 Gy. Severe complication rates for definitive radiation are about 16% to 20% and include fistula development, especially for large tumors invading the vagina, bladder, or rectum. Urethral strictures also occur in the setting of urethral-sparing treatment. Toxicity rates increase at doses greater than 65 Gy to 70 Gy. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy has come into more common use in an attempt to decrease local morbidity of the radiation 11.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping the cells from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy). When chemotherapy is placed directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, an organ, or a body cavity such as the abdomen, the drugs mainly affect cancer cells in those areas (regional chemotherapy). The way the chemotherapy is given depends on the type of cancer and where the cancer formed in the urethra.

The literature on chemotherapy for urethral carcinoma is anecdotal in nature and restricted to retrospective, single-center case series or case reports 12. A wide variety of agents used alone or in combination have been reported over the years, and their use has largely been extrapolated from experience with other urinary tract tumors.

For squamous cell cancers, agents that have been used in penile cancer or anal carcinoma include 12:

- Cisplatin.

- 5-Fluorouracil.

- Bleomycin.

- Methotrexate.

- Irinotecan.

- Gemcitabine.

- Paclitaxel.

- Docetaxel.

- Mitomycin-C.

Chemotherapy for transitional cell urethral tumors is extrapolated from experience with transitional cell bladder tumors and, therefore, usually contains the following 8:

- Methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC).

- Paclitaxel.

- Carboplatin.

- Ifosfamide, with occasional complete responses.

Chemotherapy has been used alone for metastatic disease or in combination with radiation therapy and/or surgery for locally advanced urethral cancer. It may be used in the neoadjuvant setting with radiation therapy in an attempt to increase the resectability rate or in an attempt at organ preservation 10. However, the impact of any of these regimens on survival is not known for any stage or setting.

Active surveillance

Active surveillance is following a patient’s condition without giving any treatment unless there are changes in test results. It is used to find early signs that the condition is getting worse. In active surveillance, patients are given certain exams and tests, including biopsies, on a regular schedule.

Urethral cancer prognosis

The prognosis (chance of recovery) of urethral cancer depends on the following factors 7:

- The anatomical location of the primary tumor.

- The size of the tumor.

- The stage of the cancer.

- The depth of invasion of the tumor.

Superficial tumors located in the distal urethra of both the female and male are generally curable. However, deeply invasive lesions are rarely curable by any combination of therapies. In men, the prognosis of tumors in the distal (pendulous) urethra is better than for tumors of the proximal (bulbomembranous) and prostatic urethra, which tend to present at more advanced stages 13. Likewise, distal urethral tumors tend to occur at earlier stages in women, and they appear to have a better prognosis than proximal tumors 14.

Distal cancers of the male urethra exhibit significantly improved survival rates compared with proximal tumors, and present a cure rate which can reach 90% thanks to a generally earlier detection referable to more evident symptoms 15. Proximal neoplasms are usually invasive and more aggressive at presentation and require extended surgery including resection of the penis, urethra, scrotum, and pubic bone with radical cystoprostatectomy. Disease-free survival for these patients is reported to be between 33% and 45% 16.

A study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database concluded that, set againsttransitional cell carcinoma, advanced age, higher grade, higher stage, systemic metastases, other histology (non-squamous cell carcinoma, nonadenocarcinoma), and no surgery versus radical resection were predictive of increased likelihood of death as well as death from disease. As compared with transitional cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma was associated with a lower likelihood of death and death from disease. This study illuminates prognostic indicators that previous, smaller studies were unable to reveal, yet it is limited by its lack of data regarding tumor location 17.

Another study using the SEER database found patient gender had a significant influence on the histologic variant of primary urethral cancer found at the time of presentation and diagnosis. The most common histology in men was transitional cell carcinoma (134, 53.6%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (87, 34.8%) and adenocarcinoma (29, 11.6%). The most common histology in women was adenocarcinoma (79, 46.7%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (43, 25.4%) and transitional cell carcinoma (42, 24.9%). adenocarcinoma cases of primary urethral cancer have the highest proportion of locally advanced (T3 and T4) disease for males and females, at 41% and 65%, respectively. In male primary urethral cancer, nodal and metastatic spread is most common in squamous cell carcinoma, at 37% and 15%, respectively. However, in female primary urethral cancer, nodal and metastatic spread is most common in UC cases, at 26% and 19%, respectively 18.

In patients treated with radiation therapy, complications include urethral stricture, radiation cystitis/urethritis, bowel irritation, fibrosis, infection, bleeding, and, rarely, fistula formation or secondary cancers; the overall risk of complication is roughly 20% 19.

Patients treated with urethrectomy or partial penectomy have a lower risk of complications from urethral stricture formation or development of urethral fistulae, but these risks should be addressed with the patient prior to surgery. Urinary incontinence may result from bladder overactivity and severe urgency or from damage to the external sphincter, which may lead to stress incontinence or progress to total urinary incontinence.

Tumor recurrence leads to erosion or abscess of the penile, scrotal, and perineal skin. Necrotic tissue at these sites may lead to poor wound healing and the development of fistulae and abscesses, culminating in sepsis.

In patients treated with radical cystoprostatectomy, complications include bowel obstruction, infection, and leakage, primarily due to the use of intestinal or colonic conduits for urinary diversion.

The perioperative mortality rate is 1-2%. The local tumor recurrence rate is approximately 50%.

References- Swartz MA, Porter MP, Lin DW, et al.: Incidence of primary urethral carcinoma in the United States. Urology 68 (6): 1164-8, 2006.

- Wiener JS, Walther PJ: A high association of oncogenic human papillomaviruses with carcinomas of the female urethra: polymerase chain reaction-based analysis of multiple histological types. J Urol 151 (1): 49-53, 1994.

- Grigsby PW, Corn BW: Localized urethral tumors in women: indications for conservative versus exenterative therapies. J Urol 147 (6): 1516-20, 1992.

- Pavlica P, Barozzi L, Menchi I: Imaging of male urethra. Eur Radiol 13 (7): 1583-96, 2003.

- Dayyani F, Hoffman K, Eifel P, Guo C, Vikram R, Pagliaro LC, et al. Management of advanced primary urethral carcinomas. BJU Int. 2014 Jul. 114 (1):25-31.

- Tsai YS, Yang WH, Tong YC, Lin JS, Pan CC, Tzai TS. Experience with primary urethral carcinoma from the blackfoot disease-endemic area of South Taiwan: increased frequency of bulbomembranous adenocarcinoma?. Urol Int. 2005. 74(3):229-34.

- Urethra. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2010, pp 508-9.

- Trabulsi DJ, Gomella LG: Cancer of the urethra and penis. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, pp 1272-79.

- Karnes RJ, Breau RH, Lightner DJ: Surgery for urethral cancer. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 445-57, 2010.

- Cohen MS, Triaca V, Billmeyer B, et al.: Coordinated chemoradiation therapy with genital preservation for the treatment of primary invasive carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol 179 (2): 536-41; discussion 541, 2008.

- Koontz BF, Lee WR: Carcinoma of the urethra: radiation oncology. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 459-66, 2010.

- Trabulsi EJ, Hoffman-Censits J: Chemotherapy for penile and urethral carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am 37 (3): 467-74, 2010.

- Dalbagni G, Zhang ZF, Lacombe L, et al.: Male urethral carcinoma: analysis of treatment outcome. Urology 53 (6): 1126-32, 1999.

- Gheiler EL, Tefilli MV, Tiguert R, et al.: Management of primary urethral cancer. Urology 52 (3): 487-93, 1998.

- [Guideline] Gakis G, Witjes JA, Compérat E, Cowan NC, De Santis M, Lebret T, et al. EAU Guidelines on Primary Urethral Carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2013 Nov. 64(5):823-830.

- Lucarelli G, Spilotros M, Vavallo A, Palazzo S, Miacola C, Forte S, et al. A Challenging Surgical Approach to Locally Advanced Primary Urethral Carcinoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 May. 95 (19):e3642.

- Rabbani F. Prognostic factors in male urethral cancer. Cancer. Jun 1 2011 [epub 2010 Dec 14]. 117(11):2426-2434.

- Aleksic I, Rais-Bahrami S, Daugherty M, Agarwal PK, Vourganti S, Bratslavsky G. Primary urethral carcinoma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data analysis identifying predictors of cancer-specific survival. Urol Ann. 2018 Apr-Jun. 10 (2):170-174.

- Grivas PD, Davenport M, Montie JE, Kunju LP, Feng F, Weizer AZ. Urethral cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2012 Dec. 26(6):1291-314.