What is a urinary tract infection

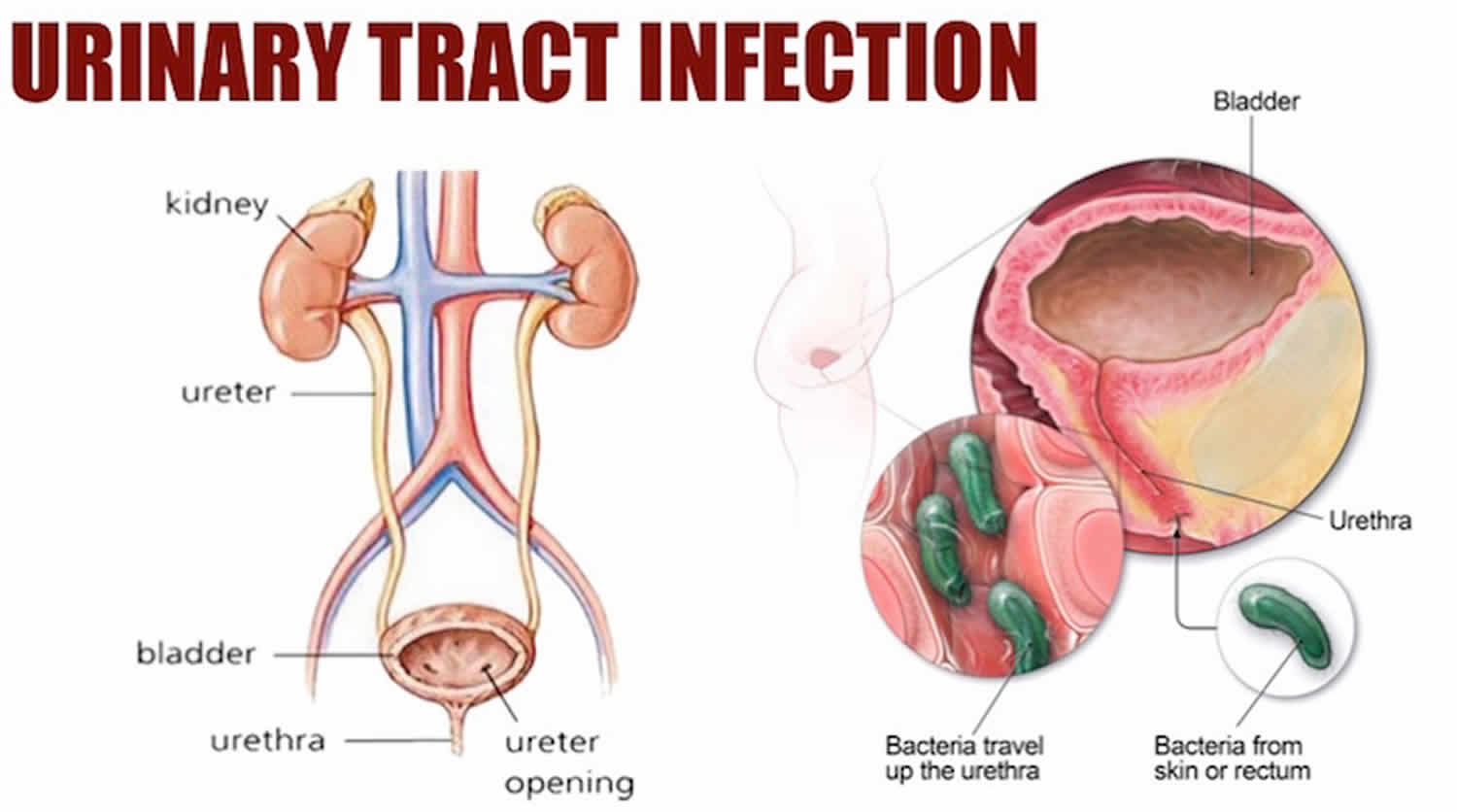

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection in any part of your urinary system — your kidneys (pyelonephritis), ureters (ureteritis), bladder (cystitis) and urethra (urethritis). A urinary tract infection is caused by bacteria entering your urinary tract, leading to an infection in the bladder, ureters (tubes that connect the kidneys to the bladder), urethra (tube connecting the bladder to the outside world), or kidneys. A urinary tract infection can affect any part of the urinary system, but most commonly occurs in the bladder (cystitis) and/or urethra (urethritis). Urinary tract infections can be painful and annoying, but usually clear up with a course of antibiotics. If untreated, urinary tract infections can lead to kidney infection, so it’s important to visit your doctor for early treatment.

The urinary system is your body’s drainage system for removing wastes and extra water. The urinary system includes two kidneys, two ureters, a bladder, and a urethra. Urinary tract infections are the second most common type of infection in the body.

Urinary tract infections don’t always cause signs and symptoms, but when they do you may notice:

- Pain or burning when you urinate

- Fever, tiredness, or shakiness

- A need to urinate small amounts often, or with urgency

- Pressure or feel uncomfortable in your lower belly

- Urine that smells bad or looks cloudy or reddish (a sign of blood in the urine)

- Pain in your back or side below the ribs

- Pelvic pain, in women — especially in the center of the pelvis and around the area of the pubic bone

People of any age or sex can get urinary tract infections. But about 30 times as many women get urinary tract infections as men 1. The annual incidence of physician-diagnosed UTIs in the United States is greater than 10% for females and 3% for males, and more than 60% of females will be diagnosed with a UTI in their lifetime 2. Individual risk for UTI depends on various factors, including age, sexual activity, family history, medical comorbidities and an individual history of UTI 3. You’re also at higher risk if you have diabetes, need a tube (catheter) to drain your bladder, or have a spinal cord injury.

The increased rate of urinary infection in the female population is explained by the difference in length of the male and female urethra. Most urinary tract infections occur when bacteria ascend from the genital region through the urethra and into the urinary bladder above. The average female urethra is approximately 4 cm long, permitting easy entry of bacteria into the bladder and cause infection. The average male urethra is 15-20 cm long, providing better protection against infection by way of its increased length. Besides the increased physical distance bacteria must travel to cause infection, the male urethra has a greater surface area to secrete antibodies to combat infection of the urinary tract. However, males at both ends of the age spectrum (mainly infants <1 year of age and elderly men with prostatic hypertrophy) exhibit a higher incidence of UTI, and other conditions in males (diabetes, spinal cord injury, catheter use) also promote UTI 4. Among individuals with upper-tract UTI (pyelonephritis), males exhibit greater morbidity and mortality than females 5, suggesting that non-anatomical differences may be at work in these more severe infections.

Urinary tract infection also has special significance in children for a number of reasons. Firstly, urinary tract infection is less easily diagnosed and thus more likely to progress to a serious extent if the problem infection is not treated. Also, urinary tract infections during childhood may be the first sign of “vesico-ureteric reflux” in which urine is allowed to flow back from the bladder to the kidneys. If left untreated, these patients may develop long-term kidney problems. When managed appropriately however, these long term problems are most often avoided.

If you think you have a urinary tract infection it is important to see your doctor. Your doctor can tell if you have a urinary tract infection with a urine test. Treatment is with antibiotics. Your doctor will usually prescribe a course of antibiotics that should get rid of the symptoms in a few days.

As with any course of antibiotics, it is important to complete the entire course, even if your symptoms have settled down or disappeared.

Sometimes, people with a kidney infection or those at risk of complications may need to be treated in a hospital.

The urinary tract infection is usually an isolated event, which will never recur in 90% of patients affected. In the vast majority of cases, the simple lower urinary tract infection will be easily treated with a 3-5 day course of oral antibiotics. Upper urinary tract infections may require admission to hospital for a short course of intravenous antibiotics with an oral course to be completed on discharge. The symptoms of infection will gradually subside of the course of treatment.

Recurrent urinary tract infections therefore occur in 10% of patients following their first event. The significance of recurrent infection is determined through assessment of urinary tract function. If the urinary tracts are normal, there is little chance that infection will spread to the kidneys and cause renal impairment. If the urinary tracts are abnormal (e.g. kidney stones) and an associated disease such as diabetes is present, the infection will more likely spread to the kidneys where repeat infection will result in long-term kidney impairment.

See a doctor if:

- you’re a man with symptoms of a urinary tract infection

- you’re pregnant and have symptoms of a urinary tract infection

- your child has symptoms of a urinary tract infection

- you’re caring for someone elderly who may have a urinary tract infection

- you have not had a urinary tract infection before

- you have blood in your pee

- your symptoms do not improve within a few days

- your symptoms come back after treatment

If you have symptoms of a sexually transmitted infection (STI), you can also get treatment from a sexual health clinic.

You are at greater risk of developing complications from a urinary tract infection and should seek medical advice promptly if you:

- have existing kidney disease, diabetes, or another chronic condition

- are pregnant

- are over the age of 65

- or have one or more of the following symptoms – high temperature 100.4 °F (38°C or above), shivering, nausea and/or vomiting, diarrhea or worsening pain in your abdomen, pelvis or back.

Children and babies and urinary tract infections

See your doctor promptly if you think your child or baby has a urinary tract infection (or another infection). Although urinary tract infection in children can usually be treated quickly and effectively, serious complications can occur if left untreated. This includes scarring of the kidneys, which may cause kidney disease and high blood pressure (hypertension).

Urinary tract anatomy

Urine is generally considered sterile. The urinary tract is the body’s drainage system for removing urine, which is made up of wastes and extra fluid. The urinary system can be divided into the upper urinary tract and lower urinary tract:

- Upper urinary tract consists of the kidneys (renal parenchyma and collecting system) and the ureters

- Kidneys. Two bean-shaped organs, each about the size of a fist. They are located just below your rib cage, one on each side of your spine. Every day, your kidneys filter about 120 to 150 quarts of blood to remove wastes and balance fluids. This process produces about 1 to 2 quarts of urine per day.

- Ureters. Thin tubes of muscle that connect your kidneys to your bladder and carry urine to the bladder.

- Lower urinary tract includes the bladder (responsible for storage and elimination of urine), the urethra (tube through which urine exits the bladder to the outside world), and prostate in men. In the female, the urethra exits the bladder near the vaginal area, the vagina could contribute to contamination of urine specimens. In the male, the urethra exits the bladder, passes through the prostate, and then through the penile urethra. The foreskin when present may contribute to infection in select instances.

- Bladder. A hollow, muscular, balloon-shaped organ that expands as it fills with urine. The bladder sits in your pelvis between your hip bones. A normal bladder acts like a reservoir. It can hold 1.5 to 2 cups of urine. Although you do not control how your kidneys function, you can control when to empty your bladder. Bladder emptying is known as urination.

- Urethra. A tube located at the bottom of the bladder that allows urine to exit the body during urination.

All parts of the urinary tract—the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra—must work together to urinate normally. The urinary tract is important because it filters wastes and extra fluid from the bloodstream and removes them from the body.

Figure 1. Urinary tract anatomy

Figure 2. Urinary bladder anatomy

Figure 3. Urinary bladder anatomy

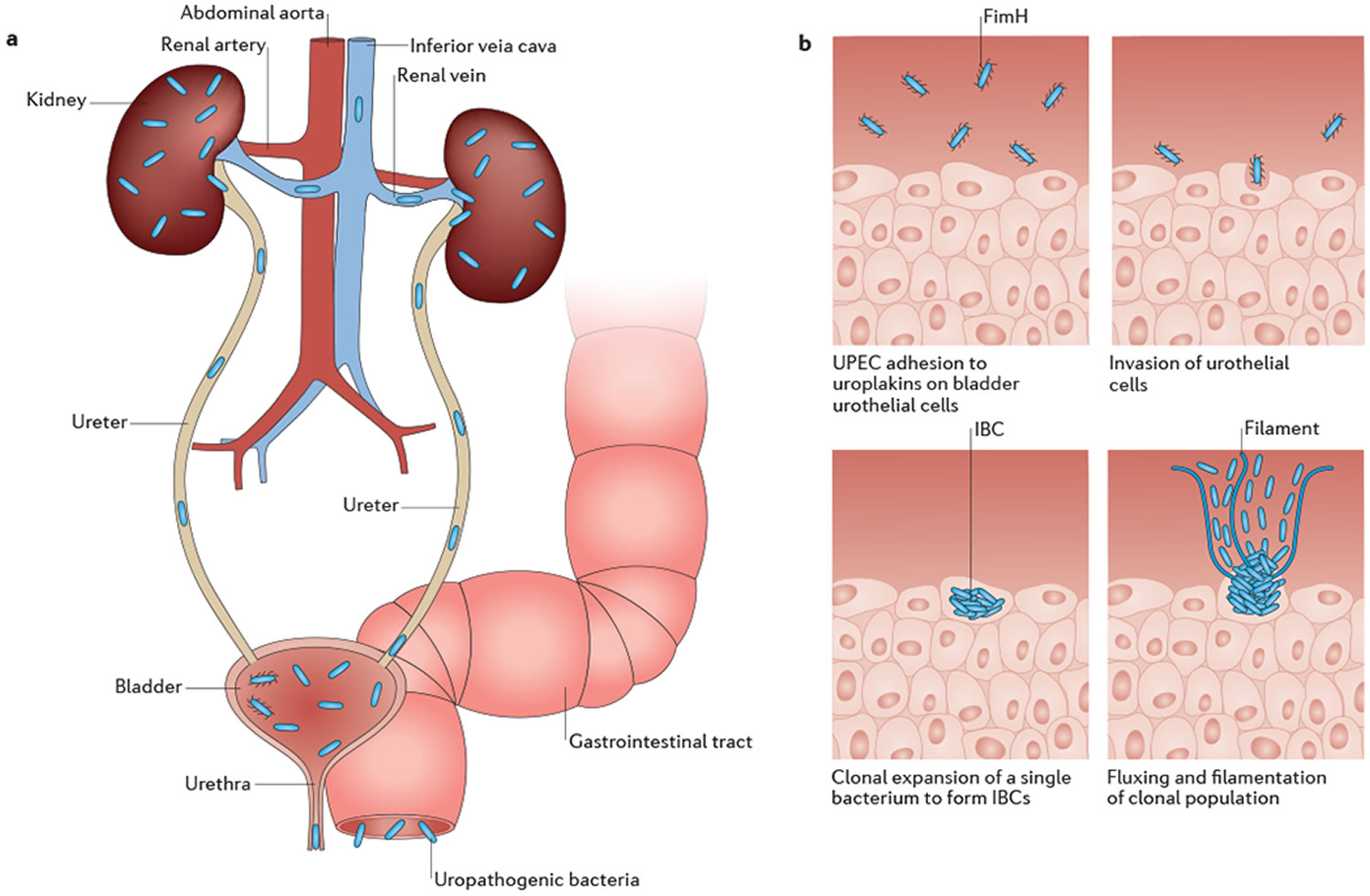

Figure 4. Urinary tract infection pathogenesis

Footnotes: (A) Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) colonizing the gastrointestinal tract, perineum or vagina inoculate the urethra and ascend into the bladder. Isolated infections of the bladder are termed cystitis, and result in the classic urinary tract infection (UTI) symptoms, such as urinary frequency, urinary urgency, dysuria, and suprapubic tenderness. Bacteria can also ascend the ureters to the kidneys, where they cause a kidney infection termed pyelonephritis that can result in fever, chills and flank pain. Finally, bacteria can invade the bloodstream, causing bacteremia that can eventually lead to septic shock. (B) In the bladder, individual bacteria adhere to and invade superficial urothelial umbrella cells in a FimH-dependent manner. There, they undergo clonal expansion to form biofilm-like intracellular bacterial communities (IBCs), where they can evade mechanical and immunological clearance mechanisms by the host. Bacteria then form filaments that flux out of the umbrella cells into the bladder lumen, where they can subsequently bind to neighboring cells and begin a new infection cycle.

[Source 6 ]Can my eating, diet, and nutrition help prevent bladder infections?

Experts don’t think eating, diet, and nutrition play a role in preventing or treating bladder infections. Some research showed that cranberry juice, extract, gelatinized products, cranberry capsules and whole cranberries, have been used with increasing frequency to prevent UTI 7, 8. A 2017 meta-analysis of 7 randomized controlled studies conducted in 1,498 women aged ≥ 18 years with a history of UTI showed that cranberry reduced the risk of UTI by 26% 9. In addition, research shows that cranberry products are not effective in treating a bladder infection if you already have one 10, 11, 12.

The benefit of cranberry products for the prevention of recurrent UTI in children is less clear. Moreover, long-term, regular consumption of cranberry products can be difficult, especially for young children 8.

Probiotics have been used for the prevention of UTI in children and adults 13, 14, 15. A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis of 6 randomized and quasi-randomized controlled studies involving 352 children and adults with UTI found no significant reduction in the risk of recurrent UTI between patients treated with probiotics and placebo with wide confidence intervals 15. The authors commented that a benefit cannot be ruled out as the data were few and derived from small studies with poor methodological reporting.

There’s mixed evidence that cranberry can help to prevent urinary tract infections:

- In a 2016 year-long study of 147 women living in nursing homes 16, taking two daily cranberry capsules decreased bacteria levels in their urine in the first 6 months of the study, but didn’t decrease their frequency of urinary tract infections over the year of the study, compared to taking a placebo. The two capsules together contained as much proanthocyanidin, a compound that is believed to protect against bacteria, as 20 ounces of cranberry juice.

- A 2012 research review of 13 clinical trials 17 suggested that cranberry may help reduce the risk of urinary tract infections in certain groups, including women with recurrent urinary tract infections, children, and people who use cranberry-containing products more than twice daily.

- A 2012 research review of 24 clinical trials 18 concluded that cranberry juice and supplements don’t prevent urinary tract infections but many of the studies were poor quality.

Cranberry hasn’t been shown to be effective as a treatment for an existing urinary tract infection.

Can drinking liquid help prevent or relieve bladder infections?

Yes. Drink six to eight, 8-ounce glasses of liquid a day. Talk with a health care professional if you can’t drink this amount due to other health problems, such as urinary incontinence, urinary frequency, or kidney failure. The amount of liquid you need to drink depends on the weather and your activity level. If you live, work, or exercise in hot weather, you may need more liquid to replace the fluid you lose through sweat.

Types of UTI

When discussing UTI’s it is important to distinguish among the following terms:

- Contamination – organisms are introduced during collection or processing of urine. No health care concerns

- Asymptomatic bacteriuria (Colonization) – organisms are present in the urine but are causing no illness or symptoms. Depending on the circumstances, significance is variable, and the patient often does not require treatment

- Infection (urinary tract infection or UTI) – the combination of a pathogen(s) within the urinary system and symptoms and/or inflammatory response to the pathogen(s) requiring treatment

- Uncomplicated UTI – infection in a healthy, non-pregnant, pre-menopausal female patient with anatomically and functionally normal urinary tract

- Complicated UTI – infection associated with factors increasing colonization and decreasing efficacy of therapy

- Recurrent UTI – occurs after documented infection that had resolved. Defined as 2 or more infections in 6 months, or > 3 infections in 12 months

- Reinfection UTI – a new event with reintroduction of bacteria into urinary tract or by different bacteria

- Persistent UTI – UTI caused by same bacteria from focus of infection

Each type of urinary tract infection may result in more-specific signs and symptoms, depending on which part of your urinary tract is infected.

The types of urinary tract infections include:

Cystitis

Cystitis is the medical term for inflammation of the bladder. Most of the time, the bladder inflammation is caused by a bacterial infection, and it’s called a urinary tract infection (UTI). Most cases of cystitis are caused by a type of Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria. A bladder infection can be painful and annoying, and it can become a serious health problem if the infection spreads to your kidneys.

Less commonly, cystitis may occur as a reaction to certain drugs, radiation therapy or potential irritants, such as feminine hygiene spray, spermicidal jellies or long-term use of a catheter. Cystitis may also occur as a complication of another illness, such as diabetes, kidney stones, an enlarged prostate or spinal cord injuries.

Cystitis is common in women because women have a shorter urethra, which cuts down on the distance bacteria must travel to reach the bladder and the female genital area often harbors bacteria that can cause cystitis. In men without any predisposing health issues, cystitis is rare.

Women at greatest risk of UTIs include those who:

- Are sexually active. Sexual intercourse can result in bacteria being pushed into the urethra.

- Use certain types of birth control. Women who use diaphragms are at increased risk of a UTI. Diaphragms that contain spermicidal agents further increase your risk.

- Are pregnant. Hormonal changes during pregnancy may increase the risk of a bladder infection.

- Have experienced menopause. Altered hormone levels in postmenopausal women are often associated with UTIs.

Other risk factors in both men and women include:

- Interference with the flow of urine. This can occur in conditions such as a stone in the bladder or, in men, an enlarged prostate.

- Changes in the immune system. This can happen with certain conditions, such as diabetes, HIV infection and cancer treatment. A depressed immune system increases the risk of bacterial and, in some cases, viral bladder infections.

- Prolonged use of bladder catheters. These tubes may be needed in people with chronic illnesses or in older adults. Prolonged use can result in increased vulnerability to bacterial infections as well as bladder tissue damage.

Signs and symptoms of cystitis often include:

- A strong, persistent urge to urinate

- A pain, burning or stinging sensation when urinating (dysuria)

- Passing frequent, small amounts of urine

- Needing to urinate more often and urgently than usual

- Urine that’s dark, cloudy or strong smelling

- Blood in the urine (hematuria)

- Pelvic discomfort

- A feeling of pressure in the lower abdomen

- Low-grade fever

Signs and symptoms of cystitis in young children may also include:

- a high temperature – they feel hotter than usual if you touch their neck, back or tummy

- wetting themselves or new episodes of accidental daytime wetting

- reduced appetite and being sick

- weakness and irritability

In older, frail people with cognitive impairment (such as dementia) and people with a urinary catheter, cystitis symptoms may also include:

- changes in behavior, such as acting confused or agitated (delirium)

- wetting themselves more than usual

- shivering or shaking (rigors)

Cranberry juice or tablets containing proanthocyanidin are often recommended to help reduce the risk of recurrent bladder infections for some women. But research in this area is conflicting. Some smaller studies demonstrated a slight benefit, but larger studies found no significant benefit.

Although these preventive self-care measures aren’t well-studied, doctors sometimes recommend the following for repeated bladder infections 19:

- Drink plenty of water. Drinking lots of fluids is especially important if you’re getting chemotherapy or radiation therapy, particularly on treatment days.

- Urinate frequently. If you feel the urge to urinate, don’t delay using the toilet.

- Wipe from front to back after a bowel movement. This prevents bacteria in the anal region from spreading to the vagina and urethra.

- Take showers rather than tub baths. If you’re susceptible to infections, showering rather than bathing may help prevent them.

- Gently wash the skin around the vagina and anus. Do this daily, but don’t use harsh soaps or wash too vigorously. The delicate skin around these areas can become irritated.

- Empty your bladder as soon as possible after intercourse. Drink a full glass of water to help flush bacteria.

- Avoid using deodorant sprays or feminine products in the genital area. These products can irritate the urethra and bladder.

The usual treatment for bacterial cystitis is antibiotics. Which antibiotics are used and for how long depend on your overall health and the bacteria found in your urine.

Treatment for other types of cystitis depends on the underlying cause.

Postmenopausal women may be particularly susceptible to cystitis. As a part of your treatment, your doctor may recommend a vaginal estrogen cream — if you’re able to use this medication without increasing your risk of other health problems.

If you have recurrent UTIs, your doctor may recommend longer antibiotic treatment or refer you to a doctor who specializes in urinary tract disorders (urologist or nephrologist) for an evaluation, to see if urologic abnormalities may be causing the infections. For some women, taking a single dose of an antibiotic after sexual intercourse may be helpful.

Urethritis

Urethritis is urinary tract infection affecting the urethra (a fibromuscular tube through which urine exits the body in both males and females, and through which semen exits the body in males) 20. Both bacteria and viruses may cause urethritis. Some of the bacteria that cause urethritis include E coli, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Neisseria gonorrhea 21. These bacteria also cause urinary tract infections and some sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) 22. Viral causes are herpes simplex virus (HSV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV). Urethritis has a strong association with sexually transmitted infections (STIs) 20.

- Neisseria gonorrhea is the leading cause of urethritis (gonococcal urethritis or GCU). Neisseria gonorrhea is a gram-negative diplococci bacteria transmitted through sexual intercourse. The incubation period is 2-5 days. Patients are commonly co-infected with Chlamydia trachomatis. Neisseria gonorrhea is often associated with copious purulent or mucopurulent urethral discharge in men or can be asymptomatic.

- Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common nongonococcal cause of urethritis (nongonococcal urethritis or NGU) and is also transmittable through sexual intercourse. Chlamydia trachomatis is a small gram-negative obligate intracellular parasitic bacteria. The incubation period is usually 7-14 days. It is commonly co-infected with Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhea. Chlamydia trachomatis is most commonly asymptomatic. Symptomatic patients can have burning pain while urinating (dysuria) and urethral discharge.

Other infectious causes associated with urethritis include 20:

- Mycoplasma genitalium a cause of recurrent or persistent urethritis and is commonly a causative agent in men with nongonococcal urethritis (NGU). This organism is small self-replicating bacteria lacking a cell wall. This organism can be difficult to detect given its slow-growing nature 23. Mycoplasma genitalium infections are commonly asymptomatic, however; symptoms may include dysuria, purulent or mucopurulent urethral discharge, urethral pruritus, balanitis, and posthitis.

- Trichomonas vaginalis, a flagellated parasitic protozoal STI, is a common infection affecting the urogenital tract of both men and women 24.

- Herpes simplex virus, a double-stranded DNA virus, can cause a genital infection involving the urethra. Herpes simplex virus usually presents with intense dysuria with painful genital ulcers 23.

- Adenovirus is an uncommon cause of urethritis in men. However, it should be considered in all males presenting with dysuria, meatitis, and associated conjunctivitis or constitutional symptoms 25.

- Treponema pallidum may cause urethritis from an endourethral syphilitic chancre; uncommon.

- Haemophilus influenzae is an uncommon cause of urethritis transmitted through oral sex from respiratory secretions.

- Neisseria meningitides is a gram-negative diplococcus that colonizes the nasopharynx. Transmission of this organism is through oral sex and is a less common cause of urethritis.

- Ureaplasma urealyticum and ureaplasma parvum; some studies show ureaplasma has uncommon links to urethritis. In patients that have tested positive, it is usually in younger men and men with fewer sexual partners. This causative agent should be of suspicion when other identifiable etiologies of nongonococcal urethritis are absent 26.

- Candida species are a common fungal yeast that can cause infections and irritation to the urogenital tract 27

Non-infectious causes associated with urethritis include:

- Trauma is less commonly the cause of urethritis. However, inflammation and irritation may occur with intermittent catheterization, after urethral instrumentation or from foreign body insertion.

- Irritation of the genital area may also result in urethritis from:

- Rubbing or pressure resulting from tight clothing or sex.

- Physical activity including activities such as bicycle riding.

- Irritants including various soaps, body powders, and sensitivity to the chemicals used in spermicides, contraceptive jellies, or foams

- Menopausal females with insufficient estrogen levels may develop urethritis due to the tissues of the urethra and bladder becoming thinner and dryer, causing irritation. This is a very common cause of urethritis in older women.

Sometimes the cause of urethritis is unknown.

Risks for urethritis include:

- Being a female

- Being male, ages 20 to 35

- Having many sexual partners

- High-risk sexual behavior (such as men having penetrating anal sex without a condom)

- History of sexually transmitted diseases

Signs and symptoms of urethritis may include:

- In men:

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Burning pain while urinating (dysuria)

- Discharge from penis

- Fever (rare)

- Frequent or urgent urination

- Itching, tenderness, or swelling in penis

- Enlarged lymph nodes in the groin area

- Pain with intercourse or ejaculation

- In women:

- Abdominal pain

- Burning pain while urinating

- Fever and chills

- Frequent or urgent urination

- Pelvic pain

- Pain with intercourse

- Vaginal discharge

Urethritis is commonly asymptomatic; if symptomatic, the symptoms vary based on the causative organism. The most common symptom of urethritis is urethral discharge 28.

Therapy should be directed based on the offending agent causing the urethritis. If you have a bacterial infection, you will be given antibiotics.

You may take both pain relievers for general body pain and products for localized urinary tract pain, plus antibiotics.

People with urethritis who are being treated should avoid sex, or use condoms during sex. Your sexual partner must also be treated if the condition is caused by an infection.

Urethritis caused by trauma or chemical irritants is treated by avoiding the source of injury or irritation.

Urethritis that does not clear up after antibiotic treatment and lasts for at least 6 weeks is called chronic urethritis. Different antibiotics may be used to treat this problem.

Pyelonephritis

Kidney infection (pyelonephritis) is a type of urinary tract infection (UTI) that generally begins in your urethra or bladder and travels to one or both of your kidneys.

A kidney infection (pyelonephritis) requires prompt medical attention. If not treated properly, a kidney infection can permanently damage your kidneys or the bacteria can spread to your bloodstream and cause a life-threatening infection.

Signs and symptoms of a kidney infection might include:

- Upper back and side (flank) pain or groin pain

- High fever

- Shaking and chills

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Frequent urination

- Strong, persistent urge to urinate

- Burning sensation or pain when urinating

- Pus or blood in your urine (hematuria)

- Urine that smells bad or is cloudy

Seek immediate medical attention if you have kidney infection symptoms combined with bloody urine or nausea and vomiting.

If left untreated, a kidney infection can lead to potentially serious complications, such as:

- Kidney scarring. This can lead to chronic kidney disease, high blood pressure and kidney failure.

- Blood poisoning (septicemia). Your kidneys filter waste from your blood and return your filtered blood to the rest of your body. Having a kidney infection can cause the bacteria to spread through your bloodstream.

- Pregnancy complications. Women who develop a kidney infection during pregnancy may have an increased risk of delivering low birth weight babies.

Antibiotics are the first line of treatment for kidney infections. Which drugs you use and for how long depend on your health and the bacteria found in your urine tests.

Usually, the signs and symptoms of a kidney infection begin to clear up within a few days of treatment. But you might need to continue antibiotics for a week or longer. Take the entire course of antibiotics recommended by your doctor even after you feel better.

Your doctor might recommend a repeat urine culture to ensure the infection has cleared. If the infection is still present, you’ll need to take another course of antibiotics.

If your kidney infection is severe, your doctor might admit you to the hospital. Treatment might include antibiotics and fluids that you receive through a vein in your arm (intravenously). How long you’ll stay in the hospital depends on the severity of your condition.

Ureteritis

Ureteritis is urinary tract infection affecting the ureters. Ureters carry urine from your kidneys to the bladder, where it’s stored until it exits your body through the urethra.

Urinary tract infection possible complications

Complications of urinary tract infections aren’t common, but they can be serious and require immediate treatment by a doctor. They usually affect people diagnosed with diabetes, a weakened immune system, men with recurrent urinary tract infections, or women who are pregnant.

Lower urinary tract infections, such as cystitis (urinary tract infection affecting the bladder) or urethritis (urinary tract infection affecting the urethra), don’t often cause complications if they are treated properly.

If a urinary tract infection is left untreated, bacteria may travel to the kidneys causing kidney infection, damage and even kidney failure. Blood poisoning can happen and occurs when the infection spreads from the kidneys to the blood-stream.

If the infection moves to the kidneys, there may be high fever, back pain, diarrhea and vomiting. If you have these symptoms, it is important to see your doctor.

Sometimes complications can occur, especially in people with weakened immune systems or upper urinary tract infections. These can include:

- Recurrent infections, especially in women who experience two or more urinary tract infections in a six-month period or four or more within a year.

- Permanent kidney damage or kidney failure from an acute or chronic kidney infection (pyelonephritis) due to an untreated urinary tract infection.

- Increased risk in pregnant women of delivering low birth weight or premature infants.

- Urethral narrowing (stricture) in men from recurrent urethritis, previously seen with gonococcal urethritis.

- Inflamed prostate in men (prostatitis)

- Sepsis (blood poisoning): a serious infection that can develop when the urinary tract infection spreads from the kidneys to the blood.

Table 1. Risk Factors for Complicated Urinary Tract Infections*

| Patient characteristics |

|

|

|

|

|

| Medical conditions |

|

|

| Urologic conditions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Footnotes:

* Increased chance of treatment failure.

† Some experts consider the following groups to be uncomplicated: healthy post-menopausal women; patients with well-controlled diabetes; and patients with recurrent cystitis that responds to treatment.

[Source 29]How do you get a urinary tract infection?

Urinary tract infections typically occur when bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli) that live in your digestive system enter the urinary tract through the urethra and begin to multiply in the bladder. Although the urinary system is designed to keep out such microscopic invaders, these defenses sometimes fail. When that happens, bacteria may take hold and grow into a full-blown infection in the urinary tract.

The most common urinary tract infections occur mainly in women and affect the bladder and urethra.

- Infection of the bladder (cystitis). This type of urinary tract infection is usually caused by Escherichia coli (E. coli), a type of bacteria commonly found in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. However, sometimes other bacteria are responsible. Sexual intercourse may lead to cystitis, but you don’t have to be sexually active to develop it. All women are at risk of cystitis because of their anatomy — specifically, the short distance from the urethra to the anus and the urethral opening to the bladder.

- Infection of the urethra (urethritis). This type of urinary tract infection can occur when gastrointestinal bacteria spread from the anus to the urethra. Also, because the female urethra is close to the vagina, sexually transmitted infections, such as herpes, gonorrhea, chlamydia and mycoplasma, can cause urethritis.

Urinary tract infections are more common in women than men. This is because in women, the urethra is closer to the anus than it is in men, and is also shorter. This means the chances of bacteria entering the urinary system are greater in women.

Women have a 1-in-3 chance of developing a urinary tract infection in their lifetime. The risk of developing a urinary tract infection increases with age for both men and women.

Women are more likely to develop a urinary tract infection if they:

- Are sexually active: This is because having sex can irritate the urethra. When this happens it allows bacteria to travel more easily though the urethra and into the bladder.

- Use a diaphragm as contraception: The diaphragm can put pressure on the bladder and stop it from emptying properly.

- Develop an irritation to spermicide used on condoms: Some women develop a vaginal irritation from spermicide, making the area more vulnerable to infection.

- Are pregnant: Hormonal changes during pregnancy make women more vulnerable to urinary tract infections.

- Have gone through menopause: When levels of the hormone oestrogen decline, women may become more vulnerable to developing a urinary tract infection.

Overall, people are more likely to develop a urinary tract infection if they have:

- Kidney stones or another condition that blocks the urinary tract.

- A condition that stops the bladder from emptying fully (e.g. an enlarged prostate that presses on the bladder).

- A urinary catheter (a tube inserted into the urethra going into the bladder; often used after surgery if a person has to remain in bed for some time).

- A medical condition involving the bladder or kidneys (e.g. some babies are born with problems that stop the urine travelling properly though the urinary system).

- A medical condition that weakens the immune system (e.g. diabetes).

- Medical treatments that weaken the immune system (e.g. chemotherapy).

- A recent medical procedure on the urinary tract.

Babies and older people are also more prone to urinary tract infections.

Men with an enlarged prostate may be more prone to urinary tract infections, as this may affect the flow of urine.

Urinary tract infection women

Women of all ages get urinary tract infections up to 30 times more often than men do 1, 30. Also, as many as 4 in 10 women who get a urinary tract infection will get at least one more within six months of an initial infection 31, 32. Healthy women with normal urologic anatomy account for most patients who have recurrent UTIs 33. Recurrent UTI is typically defined as three or more UTIs in 12 months, or two or more infections in six months 31.

Urinary tract infections are caused by bacteria or, rarely, yeast getting into your urinary tract. Once there, they multiply and cause inflammation (swelling) and pain. You can help prevent urinary tract infections by wiping from front to back after using the bathroom.

Women get urinary tract infections more often because a woman’s urethra (the tube from the bladder to where the urine comes out of the body) is shorter than a man’s. This makes it easier for bacteria to get into the bladder. A woman’s urethral opening is also closer to both the vagina and the anus, the main source of germs such as Escherichia coli (E. coli) that cause urinary tract infections 34.

You may be at greater risk for a urinary tract infection if you 35:

- Are sexually active. Sexual activity can move germs that cause urinary tract infections from other areas, such as the vagina, to the urethra.

- Use a diaphragm for birth control or use spermicides (creams that kill sperm) with a diaphragm or with condoms. Spermicides can kill good bacteria that protect you from urinary tract infections.

- Are pregnant. Pregnancy hormones can change the bacteria in the urinary tract, making urinary tract infections more likely. Also, many pregnant women have trouble completely emptying the bladder, because the uterus (womb) with the developing baby sits on top of the bladder during pregnancy. Leftover urine with bacteria in it can cause a urinary tract infection.

- Have gone through menopause. After menopause, loss of the hormone estrogen causes vaginal tissue to become thin and dry. This can make it easier for harmful bacteria to grow and cause a urinary tract infection.

- Have diabetes, which can lower your immune (defense) system and cause nerve damage that makes it hard to completely empty your bladder

- Have any condition, like a kidney stone, that may block the flow of urine between your kidneys and bladder

- Have or recently had a catheter in place. A catheter is a thin tube put through the urethra into the bladder. Catheters drain urine when you cannot pass urine on your own, such as during surgery.

Urinary tract infection symptoms in women

If you have a urinary tract infection, you may have some or all of these symptoms 36:

- Pain or burning when urinating

- An urge to urinate often, but not much comes out when you go

- Pressure in your lower abdomen

- Urine that smells bad or looks milky or cloudy

- Blood in the urine. This is more common in younger women. If you see blood in your urine, tell a doctor or nurse right away.

- Feeling tired, shaky, confused, or weak. This is more common in older women.

- Having a fever, which may mean the infection has reached your kidneys

How do urinary tract infections affect pregnancy?

Changes in hormone levels during pregnancy raise your risk for urinary tract infections. urinary tract infections during pregnancy are more likely to spread to the kidneys.

If you’re pregnant and have symptoms of a urinary tract infection, see your doctor or nurse right away. Your doctor will give you an antibiotic that is safe to take during pregnancy.

If left untreated, urinary tract infections could lead to kidney infections and problems during pregnancy, including:

- Premature birth (birth of the baby before 39 to 40 weeks)

- Low birth weight (smaller than 5 1/2 pounds at birth)

- High blood pressure, which can lead to a more serious condition called preeclampsia 37

Recurrent UTI in women

Women who get two urinary tract infections in six months or three or more UTIs within 12 months have recurrent urinary tract infections 38. Recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) are common in women, including healthy women with normal genitourinary anatomy 38. Recurrent UTI is thought to occur by ascent of uropathogens in fecal flora along the urogenital tract and by reemergence of bacteria from intracellular bacterial colonies in uroepithelial cells 38. In either mechanism, the same species that caused the initial infection is typically the reinfecting agent 33.

Escherichia coli causes approximately 75% of recurrent UTIs; most other infections are caused by Enterococcus faecalis, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella, or Staphylococcus saprophyticus 33.

Independent risk factors for recurrent UTIs in premenopausal women include sexual intercourse three or more times per week, spermicide use, new or multiple sex partners, and having a UTI before 15 years of age 38, 39. In postmenopausal women, estrogen deficiency and urinary retention are strong contributors 40. Prophylaxis with a cranberry product in premenopausal women or topical estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women may limit UTI recurrences and thereby limit antibiotic use, although data about cranberry use are conflicting. Cranberries contain proanthocyanidins, which may prevent adherence of E. coli to uroepithelial cells. Data are conflicting about the effectiveness of cranberry products for preventing recurrent UTI in premenopausal women 41. A 2012 meta-analysis 42 demonstrated a decrease in UTI rates in women who received daily cranberry tablets. However, a 2012 Cochrane review 43 found insufficient evidence to recommend routine use of cranberry products for pro-phylaxis. They are generally a low-risk intervention and may prove to be another means to reduce UTI episodes and antibiotic use. Appropriate dosing and formulation of cranberry products have not been determined. Dosages of 36 to 72 mg per day are being tested in an ongoing clinical trial 44. Cranberry tablets seem to cause less gastroesophageal reflux and nausea than cranberry juice 45, 41.

Your doctor or nurse might do tests to find out why. If the test results are normal, you may need to take a small dose of antibiotics every day to prevent infection. Your doctor may also give you a supply of antibiotics to take after sex or at the first sign of infection 46. Continuous daily and postcoital (after sex) low-dose antibiotic prophylactic regimens decrease recurrence of symptomatic UTIs by approximately 95%, although patients may revert to preprophylaxis recurrence rates once prophylaxis is discontinued 33, 47. The optimal duration of antibiotic prophylaxis is unknown. Based on consensus opinion and limited data, an initial 6 to 12-month course should be offered 47, 48. Small studies have shown effectiveness for up to five years, although long-term adverse effects such as antibiotic resistance and reversible pulmonary fibrosis from several years of nitrofurantoin use have been reported 48. Common dosing options for antibiotic prophylaxis are listed in Table 3.

Uncomplicated urinary tract infections can be treated with a three-day course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, a five-day course of nitrofurantoin, or a one-day course of fosfomycin (Monurol) 30; these regimens are preferred to fluoroquinolones to minimize antibiotic resistance. Beta-lactams are less effective. Recommended regimens are the same for women with diabetes. Compared with longer treatment durations, three-day courses of bactericidal antimicrobials are associated with fewer side effects, improved treatment adherence, and similarly low risk of progression to pyelonephritis (less than 1%) 47.

In postmenopausal women, treatment of atrophic vaginitis with topical estrogen formulations may decrease rates of UTI recurrence through effects on vaginal flora 49. In a 2008 Cochrane review 50, women treated with topical estrogen had a 50% reduction in UTI recurrence 50. Oral estrogens are less effective and confer risks associated with systemic hormone replacement, and should not be used for this purpose 50.

Evidence for intravaginal and oral Lactobacillus probiotics, oral D-mannose, acupuncture, and immunoprophylactic regimens is sparse and conflicting, and further study is warranted 15, 41, 51.

Although UTIs in women with diabetes have historically been classified as complicated 48, new limited data suggest that causative pathogens and resistance rates are comparable to those of UTIs in women without diabetes 52. Two recent systematic reviews suggest that UTIs in women with diabetes should be treated in the same manner as those in women without diabetes unless risk factors for functionally or anatomically altered voiding are present 47, 53.

Persistent bacteriuria after resolution of clinical symptoms should be considered asymptomatic bacteriuria and should not be further treated in nonpregnant women.37,38 Furthermore, treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria may increase the risk of UTI recurrence by altering normal flora 54, 55.

Table 2. Antibiotics for Uncomplicated Acute Cystitis and Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women

| Antibiotic | Dosage | Effectiveness (%) | Resistance rate (%)* | Cautions and contraindications | Adverse effects | U.S. Food and Drug Administration pregnancy category | Comments | Infectious Diseases Society of America recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line agents | ||||||||

| Fosfomycin (Monurol) | 3-g packet one time | 91 | Up to 0.6 | Hypersensitivity to fosfomycin, suspected pyelonephritis | Diarrhea, headache, nausea, vaginitis | B | Minimal change in gut flora; effective against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, ESBL-producing organisms, Enterococcus faecalis, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus | Single dose is appropriate for acute cystitis despite concerns about effectiveness |

| Nitrofurantoin | 100 mg two times per day for five days | 93 | Up to 1.6 | Glomerular filtration rate less than 40 to 60 mL per minute, history of cholestatic jaundice or hepatic dysfunction with previous use, pregnancy (greater than 38 weeks’ gestation), pulmonary or hepatic fibrosis, suspected pyelonephritis; use with caution in patients with G6PD deficiency | Flatus, headache, hemolytic anemia, nausea, neuropathy; risk of pulmonary and hepatic fibrosis with long-term use | B | Minimal change in gut flora; should be taken with meals; may turn urine orange; effective against E. faecalis, S. aureus, and Staphylococcus saprophyticus | Five-day course is as effective as three-day course of trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole for treatment of acute cystitis |

| Trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole | 160/800 mg two times per day for three days | 93 | Up to 24.2 | History of drug-induced thrombocytopenia or other hematologic disorder, local resistance rates greater than 20%, pregnancy, sulfa allergy, use in previous three to six months; use with caution in patients with hepatic or renal impairment, porphyria, or G6PD deficiency | Bone marrow suppression, electrolyte abnormalities, hepatotoxicity, nausea, nephrotoxicity, photosensitivity, rash, Stevens-Johnson syndrome | D | Alters gut flora | Three-day course is appropriate if local resistance rates do not exceed 20% |

| Second-line agents | ||||||||

| Fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin [Levaquin]) | Ciprofloxacin: 250 mg two times per day for three days Levofloxacin: 250 to 500 mg per day for three days | 90 | Ciprofloxacin: up to 17 Levofloxacin: up to 6 | Concurrent use with medications that prolong QT interval, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, local resistance rates greater than 10%, myasthenia gravis, pregnancy; use with caution in patients with renal impairment | Diarrhea, drowsiness, headache, insomnia, nausea, QT interval prolongation, tendon rupture | C | Alters gut flora; ciprofloxacin is preferred over other fluoroquinolones; limit use to patients with pyelonephritis or resistant cystitis | Three-day course is highly effective for treatment of cystitis; reserve for treatment of more severe conditions (e.g., pyelonephritis) |

| Alternative agents if first- and second-line agents are contraindicated | ||||||||

| Beta-lactams (e.g., amoxicillin/clavulanate [Augmentin], cefaclor, cefdinir, cefpodoxime, cephalexin [Keflex]) | Amoxicillin/clavulanate: 500/125 mg two times per day for three days Cefaclor: 250 mg three times per day for five days Cefdinir: 300 mg two times per day for five days Cefpodoxime: 100 mg two times per day for three days Cephalexin: 500 mg two times per day for seven days | 89 | Varies by medication | Cephalosporin or penicillin allergy, history of cholestatic jaundice with previous use; use with caution in patients with renal or hepatic impairment, history of infectious colitis, or active mononucleosis; use cephalexin with caution in patients with elevated international normalized ratios | Diarrhea (including Clostridium difficile colitis), headache, hepatotoxicity, nausea, rash, vaginitis | B | Alters gut flora; use with caution because of increasing prevalence of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli | Courses of three to seven days are appropriate if other agents cannot be used; fewer supporting data for cephalexin; high resistance rates should preclude use of amoxicillin |

Footnotes: * Resistance information is based on averages from one large 2010 multicenter analysis of 12 million outpatient cultures obtained throughout the United States 56. Fosfomycin resistance is difficult to ascertain because most laboratories do not routinely test its susceptibility. However, one international multicenter study found resistance rates of 0.6% 57 and its effectiveness was demonstrated in a 2010 meta-analysis 58. Local resistance rates may vary.

Abbreviations: ESBL = extended-spectrum beta-lactamase; G6PD = glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; NA = not available.

[Source 38 ]Antibiotic prophylaxis

Some doctors recommend long-term prophylactic use of antibiotics in women with recurring urinary tract infections. A Cochrane meta-analysis indicated positive outcomes of prophylactic use of antibiotics in young non-pregnant women with recurring UTIs 59. Results published by Ahmed et al. 60, however, show that long-term antibiotic prophylaxis had positive outcomes in patients aged 65 years and above only when continued for more than 2 years. The patients received nitrofurantoin, cephalexin, or trimethoprim. The treatment reduced the frequency of recurring symptomatic urinary tract infections and the need for additional antibiotic prescriptions 60. At the same time, a small but statistically significant increase of hospitalizations due to UTIs was observed 60.

According to European Association of Urology guidelines, antibiotic prophylaxis should be introduced when neither behavioral interventions nor non-antibiotic prevention is successful.

Table 3. Recommended Prophylactic Antibiotics for Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women

| Antibiotic | Continuous dosage | Postcoital dose |

|---|---|---|

| Commonly used first-line agents | ||

| Nitrofurantoin | 50 to 100 mg per day | 100 mg |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 40/200 mg (one-half of an 80/400-mg tablet) per day or 40/200 mg three times per week (alternative) | 40/200 mg or 80/400 mg |

| Occasionally used first-line agents | ||

| Cefaclor | 250 mg per day | — |

| Cephalexin (Keflex) | 125 to 250 mg per day | 250 mg |

| Trimethoprim | 100 mg per day | — |

| Agents not commonly used for prophylaxis | ||

| Ciprofloxacin | 125 mg per day | 125 mg |

| Fosfomycin (Monurol) | One 3-g packet every 10 days | — |

| Ofloxacin | — | 100 mg |

Footnotes: All regimens have demonstrated an expected frequency of less than one urinary tract infection per year, compared with 0.8 to 3.6 per year with placebo.

[Source 38 ]Non-antibiotic prophylactic treatment

Uro-Vaxom (OM-89®) is an immunomodulatory drug 61, 62. Uro-Vaxom (OM-89®) is effective against Escherichia coli infections, constituting 70–80% of all urinary tract infections. Women with recurring urinary tract infections treated with Uro-Vaxom (OM-89®) for 6 months had a twofold reduced further recurrence rate (67.3% vs. 32.7%) 63. Uncontrolled diabetes significantly reduced the treatment efficacy, however. In a multi-center double blind study involving 453 women, a 34% reduction of urinary tract infections was observed after 3 months of initial treatment and a 10-day boos-ter course of Uro-Vaxom (OM-89®) 64. The same treatment structure was utilized in a retrospective study of 79 patients, with Escherichia coli identified as the main pathogen in 49% of the population 62. Sixty-three per cent of those infected with Escherichia coli and 53% of the whole population had a positive response to treatment.

Uro-Vaxom (OM-89®) efficacy was also confirmed in a study involving menopausal women 65. A clinical trial was carried out with a group of patients aged 66 years on average. The number of recurrent infections in the group dropped from 3.4 to 1.8 (a reduction of 65%) after the immunomodulatory treatment 65.

Uro-Vaxom (OM-89®) oral immunomodulatory treatment for the prevention of recurring UTIs is recommended both by the European Association of Urology (EAU) in uncomplicated UTIs in women 66 and by the Polish Association of Urology in prevention of recurring urinary tract infections. The treatment helps reduce the frequency of recurring infections, patients’ symptoms, antibiotic prescriptions, and the risk of antibiotic resistance 67. To prevent recurring UTIs, Uro-Vaxom (OM-89®) is administered once a day before a meal, for a total of 90 days. The drug can be used in parallel with antibiotic treatment during the acute phase of an infection, without prior urine culture results, because it induces a strong immune response not only to E. coli, but also to other pathogens causing UTIs 67.

How can I prevent urinary tract infections?

You can take steps to help prevent a urinary tract infection. But you may follow these steps and still get a urinary tract infection.

- Urinate when you need to. Don’t go without urinating for longer than three or four hours. The longer urine stays in the bladder, the more time bacteria have to grow.

- Try to urinate before and after sex.

- Always wipe from front to back.

- Try to drink six to eight glasses of fluid per day.

- Clean the anus and the outer lips of your genitals each day.

- Do not douche or use feminine hygiene sprays.

- If you get a lot of urinary tract infections and use creams that kill sperm (spermicides), talk to your doctor or nurse about using a different form of birth control instead.

- Wear underpants with a cotton crotch. Avoid tight-fitting pants, which trap moisture, and change out of wet bathing suits and workout clothes quickly.

- Take showers, or limit baths to 30 minutes or less.

Urinary tract infections in children

Urinary tract infections are relatively common in children, particularly young children still in diapers. Girls are more likely than boys to develop a urinary tract infection, except in the first 12 months of life, when boys seem to be more susceptible. In the first year of life, UTIs are more common in boys than girls and 10 times higher in uncircumcised boys, compared with circumcised boys 68. Up to 7% of girls and 2% of boys have had a UTI by six years of age 69. The recurrence rate is 30% 69. Sexual activity increases the risk of UTI in teenage girls 70. Children who have had a UTI have a 13–19% increased risk of recurrence and 17% will develop renal scarring 71. However, few children (<4%) will develop end-stage renal failure from a UTI; this is often a result of recurrent UTIs or vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) 72.

The most common organisms that infect the urine are bacteria that normally live in the bowel, Escherichia coli accounts for 80 to 90% of UTI in children 73, 74. Other bacteria causing UTIs include Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter aerogenes, Citrobacter, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus spp., Serratia and Staphylococcus saprophyticus 75, 76. Proteus mirabilis is more common in boys than in girls 77. Streptococcus agalactiae is relatively more common in newborn infants 78. Staphylococcus saprophyticus is very common in sexually active female adolescents, accounting for ≥ 15% of UTI 79. In children with anomalies of the urinary tract (anatomic, neurologic, or functional) or compromised immune system, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus viridians, and Streptococcus agalactiae may be responsible 80, 81. Hematogenous spread of infection, an uncommon cause of UTI, may be caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and nontyphoidal Salmonella 75. Rare bacterial causes of UTI include Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Streptococcus pneumoniae 82, 83.

Wiping your child’s bottom from the front to the back (rather than from back to front) can help prevent carrying bacteria from the bowel to the urinary tract.

Viruses such as adenoviruses, enteroviruses, echoviruses, and coxsackieviruses may also cause UTI 79. Adenoviruses are known to cause hemorrhagic cystitis 84. Fungi (e.g., Candida spp., Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus spp.) are uncommon causes of UTI and occur mainly in children with an indwelling urinary catheter, anomalies of the urinary tract, long-term use of broad-spectrum antibiotic, or compromised immune system 84.

Urinary tract infections, especially ones that recur, can also be caused by your child’s bladder not emptying properly or sometimes by structural problems of the kidneys or bladder.

Underlying kidney and bladder problems

Urine is made in the kidneys and then normally flows down from the kidneys into the bladder via the ureters. From the bladder, urine can leave the body via the urethra. In some children, urine flows back up the ureters towards the kidneys rather than being passed straight down the urethra. This abnormal flow of urine is called urinary reflux or sometimes vesico-ureteric reflux.

Urinary reflux can be harmful because it not only predisposes your child to infection (because of some urine always being left in the bladder) but it can also contribute to scarring of the kidneys if the reflux is severe.

Some children (including infants and those with severe infections) need to be tested for problems with their kidneys or bladder after having a single urinary tract infection. Most children should be tested after having recurrent urinary tract infections. These tests help show any problems with the urinary tract and whether the urine is flowing in the right direction.

The tests usually include:

- a kidney and bladder ultrasound (which can show problems with the kidneys, ureters and bladder); with or without

- a bladder X-ray, known as a micturating cystourethrogram (MCUG).

In an micturating cystourethrogram (MCUG), a catheter (thin tube) is passed into the bladder and dye is injected through it. It will show what happens when your child passes urine and whether urine is flowing in the right direction.

Occasionally, special nuclear medicine scans (DMSA and MAG3) may be recommended to help detect kidney scarring or urinary reflux.

The treatment of vesico-ureteric reflux may involve ongoing use of antibiotics in some children to prevent severe or recurrent infections. Antibiotics may be initially recommended for 6 months in these cases.

Usually with time, the reflux will improve by itself. In some severe cases, surgery may be recommended to treat the reflux.

Signs and symptoms of urinary tract infections in children

Clinical signs and symptoms of a urinary tract infection depend on the age of the child. Newborns with urinary tract infection may present with jaundice, sepsis, failure to thrive, vomiting, or fever 85. In infants and young children, typical signs and symptoms include fever, strong-smelling urine, hematuria, abdominal or flank pain, and new-onset urinary incontinence 85. School-aged children may have symptoms similar to adults, including dysuria, frequency, or urgency 85. Boys are at increased risk of urinary tract infection if younger than six months, or if younger than 12 months and uncircumcised. Girls are generally at an increased risk of urinary tract infection, particularly if younger than one year 86. Physical examination findings can be nonspecific but may include suprapubic tenderness or costovertebral angle tenderness.

Symptoms of a urinary tract infection can vary. In infants and young children, symptoms are often non-specific and can include:

- fever;

- irritability;

- vomiting;

- diarrhea;

- tiredness;

- smelly urine;

- poor feeding; or

- failure to put on weight.

As children get older, the symptoms often become more specific, such as:

- pain or stinging on passing urine;

- accidentally wetting themselves when they’ve been toilet trained previously;

- abdominal or back pain; and

- going to the toilet more frequently than usual.

Fever may or may not be present.

Urinary tract infections prevention in children

In children who have had urinary tract infections, the following measures may help prevent further infections.

- Getting your child to drink plenty of fluids.

- Ensuring your child empties their bladder when they get the urge and doesn’t delay going to the toilet.

- Making sure your child properly cleans themselves and wipes from front to back after toileting.

- Avoiding bubble baths (which may irritate the urethra).

- Seeing your doctor for advice on treating constipation in children, which can contribute to problems with bladder emptying.

Urinary tract infection tests and diagnosis in children

Your doctor will ask about your child’s symptoms and perform a physical examination, looking for signs of a urinary tract infection.

To diagnose a urinary tract infection, your doctor will need to send a urine specimen to the laboratory for testing. In older children, this can easily be done by collecting a sample in a specimen jar as your child passes urine into the toilet.

In younger children, urine samples can be more difficult to collect. The most common collection method used in infants and toddlers who wear nappies is removing the nappy, waiting for the child to urinate and trying to catch some urine in a specimen jar.

Very occasionally, your doctor may need to insert a tube (catheter) through the urethra into your child’s bladder, or pass a fine needle into the bladder through the wall of the abdomen to collect a sample.

So called ‘bag urines’, where an adhesive plastic collecting bag is used to collect urine, frequently yield contaminated samples which cannot provide a diagnosis; if this method is used, it’s best that a nurse or doctor performs the collection rather than trying to do it yourself at home.

Currently, there is no consensus regarding the best method for urine collection in children who are not toilet trained 87. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that the urine specimen needs to be obtained through suprapubic aspiration or catheterization only 88. Unfortunately, suprapubic aspiration and catheterization are invasive, stressful, and may not be feasible in a primary care setting 13. On the other hand, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the Italian Society of Pediatric Nephrology (ISPN) recommend the clean-catch method as the method of choice for urine collection, reserving suprapubic aspiration or catheterization for specific situations such as a febrile child in poor general health or appears severely ill 89, 90. The Canadian Paediatric Society recommends leaving the child with the diaper off and obtaining a clean-catch urine sample when the child voids 91. If the urinalysis is abnormal, urine collection by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration would be in order 91. For children who are toilet trained, a clean-catch midstream urine specimen should be obtained after proper cleansing of the external genitalia 91.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guidelines, the diagnosis of UTI in children 2 to 24 months requires positive dipstick test (leukocyte esterase and/or nitrite test), microscopy positive for pyuria or bacteriuria, and the presence of ≥ 50,000 colony-forming unit (CFU)/ml of a uropathogen in a catheterized or suprapubic aspiration specimen 88. According to the Canadian Paediatric Society guidelines, a positive dipstick test (leukocyte esterase and/or nitrite) and a positive urine culture of a single uropathogen (≥ 100,000 CFU/ml in a midstream urine specimen, ≥ 50,000 CFU/ml in a catheterized specimen, and any organism in a suprapubic aspiration specimen) are required for the diagnosis of UTI 91. The European Association of Urology (EAU) / European Society for Paediatric Urology (ESPU) guidelines state that growth of 10,000 or even 1,000 cfu/ml of a uropathogen from a catheterized specimen or any counts from a suprapubic aspiration specimen is sufficient to diagnose a UTI 80. In toilet-trained children, a clean-catch midstream urine specimen rather than a catheterized or a suprapubic aspiration specimen should be submitted for urinalysis and urine culture 91.

Clinical judgment is important as UTI can occur, though rarely, in the absence of pyuria and that urine culture can be negative in children with UTI if a bacteriostatic/bactericidal antimicrobial agent is present in the urine or if there is ureteric obstruction preventing discharge of bacteria from the kidney to the bladder 92. UTI with low bacterial count is not uncommon if the infection is caused by non-E. coli species 93.

Treatment of urinary tract infections in children

If your child is unwell and a urinary tract infection is strongly suspected, your doctor may prescribe antibiotics as soon as the urine specimen is collected. Otherwise your doctor may wait until the result of the urine test is known.

Commonly, antibiotics are given by mouth. However, in some cases, such as in children who are extremely unwell or in very young infants, antibiotics will be given via a drip into a vein (intravenous antibiotics). Intravenous (IV) antibiotics need to be given in hospital.

Some children with urinary tract infections may be referred to a pediatrician (specialist in children’s health) for further assessment and treatment.

Currently, a second or third generation cephalosporin and amoxicillin-clavulanate are drugs of choice in the treatment of acute uncomplicated UTI 87. Intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy is recommended for infants ≤ 2 months and any child who is toxic-looking, hemodynamically unstable, immunocompromised, unable to tolerate oral medication, or not responding to oral medication. A combination of intravenous ampicillin and intravenous/intramuscular gentamycin or a third-generation cephalosporin can be used in those situations. Routine antimicrobial prophylaxis is rarely justified, but continuous antimicrobial prophylaxis should be considered for children with frequent febrile UTI.

Table 4. Antibiotics Commonly Used to Treat Urinary Tract Infections in Children

| Antibiotic | Dosing | Common side effects |

|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) | 25 to 45 mg per kg per day, divided every 12 hours | Diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, rash |

| Cefixime (Suprax) | 8 mg per kg every 24 hours or divided every 12 hours | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, flatulence, rash |

| Cefpodoxime (Vantin) | 10 mg per kg per day, divided every 12 hours | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, rash |

| Cefprozil (Cefzil) | 30 mg per kg per day, divided every 12 hours | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, elevated results on liver function tests, nausea |

| Cephalexin (Keflex) | 25 to 50 mg per kg per day, divided every 6 to 12 hours | Diarrhea, headache, nausea/vomiting, rash |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra) | 8 to 10 mg per kg per day, divided every 12 hours | Diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, photosensitivity, rash |

Urinary tract infections in children prognosis

Children with a functional or anatomic abnormality of the urinary tract or immunodeficiency are prone to UTI 94. The prognosis of UTI in the absence of vesicoureteric reflux (VUR) and renal scarring is usually good and not associated with long-term complications 95, 96. Recent studies have shown that much of the kidney scarring previously attributed to acute pyelonephritis is related to congenital renal dysplasia, high-grade vesicoureteric reflux, or urinary tract obstruction 74. Nevertheless, it has been proven beyond doubt that delay in treatment of febrile UTI or recurrent febrile UTI may lead to renal scarring 94.

Urinary tract infection signs and symptoms

Common symptoms of a urinary tract infection include:

- A burning sensation when passing urine.

- The need to urinate urgently.

- Passing urine more frequently than usual.

- Feeling the urge to urinate, but being unable to or only passing a few drops.

- Dull pain in the pelvis.

- Unpleasant smelling urine.

- Urine that is cloudy, bloody, pink or dark.

- Back pain.

- Generally feeling unwell.

- Fever.

Symptoms that may indicate that the infection involves the kidney(s) (pyelonephritis) include:

- Fever and rigors (shivering).

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Diarrhea.

- Back pain.

Urinary tract infection prognosis

Lower urinary tract infections are seldom complicated and complete recovery is expected with a short course of antibiotics. Those patients with an uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection are at no risk of developing renal failure in later life.

Upper urinary tract infections will require admission to hospital for intravenous antibiotics followed by an extended oral course of antibiotics at home following discharge from hospital. Recovery is expected with a variable but commonly small reduction in kidney function.

In women with recurrent UTIs, the quality of life is poor. About 25% of women experience such recurrences. Factors that indicate a poor outlook include 97:

- Poor overall health

- Advanced age

- Presence of kidney stones (renal calculi)

- Diabetes (especially if poorly controlled)

- Sickle cell anemia

- Presence of malignancy

- Catheterization

- Ongoing chemotherapy

- Incontinence

- Chronic diarrhea

Urinary tract infection causes

The urinary system’s job is to excrete wastes from the body in the form of urine. The kidneys act as filtration units to remove some of the body’s waste products from the blood, such as urea and ammonia. These are then converted to urine and passed through the ureters, into the bladder and then through the urethra to leave the body.

A urinary tract infection occurs when part of the urinary tract becomes infected, usually with bacteria (e.g., uropathogenic Escherichia coli [UPEC]) that live in the digestive system — where they usually live and do not cause a problem. The bacteria often enter the urinary tract through the urethra, for example from the anus. This can happen if bacteria in feces is transmitted to the urethra by toilet paper, such as when a woman wipes from back to front rather than from front to back. Women have a shorter urethra than men. This means bacteria are more likely to reach the bladder or kidneys and cause an infection. Once inside the urinary tract, these bacteria can multiply and cause an infection resulting in local irritation and inflammation.

Hematogenous spread is an uncommon cause of UTIs. The bacteria most commonly involved with hematogenous spread are Staphylococcus aureus, Candida species and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Hematogenous infection develops most often in immunocompromised patients, elderly, or neonates. Relapsing hematogenous infections can be secondary to incompletely treated prostatic or kidney parenchymal infections (e.g. emphysematous pyelonephritis).

Common causative pathogens in adult UTIs:

- Escherichia coli (80% of outpatient UTIs) 6

- Staphylococcus saprophyticus (5–15% of outpatient UTIs)

- Klebsiella

- Proteus

- Pseudomonas

- Enterobacter

- Enterococcus

- Candida

- Adenovirus type 11

Normal perineal flora:

- Lactobacillus

- Corynebacterium

- Staphylococcus

- Streptococcus

Things that increase the risk of bacteria getting into the bladder include:

- having sex

- pregnancy

- conditions that block the urinary tract – such as kidney stones

- conditions that make it difficult to fully empty the bladder – such as an enlarged prostate in men and constipation in children

- urinary catheters (a tube in your bladder used to drain urine)

- having a weakened immune system – for example, people with diabetes or people having chemotherapy

- not drinking enough fluids

- not keeping the genital area clean and dry

For most people, a urinary tract infection is a one-off illness that resolves quickly and responds to treatment with antibiotics when necessary. However, for some people, urinary tract infections are a recurrent (recurring) problem.

You are considered to have recurrent urinary tract infections if you have either:

- 2 or more urinary tract infections within 6 months, or

- 3 or more urinary tract infections within 1 year.

Risk factors for urinary tract infection

Urinary tract infections are common in women, and many women experience more than one infection during their lifetimes.

Risk factors specific to women for urinary tract infections include:

- Female anatomy. A woman has a shorter urethra than a man does, which shortens the distance that bacteria must travel to reach the bladder.

- Sexual activity. Sexually active women tend to have more urinary tract infections than do women who aren’t sexually active.

- New sexual partner. Having a new sexual partner also increases your risk.

- Certain types of birth control. Women who use diaphragms for birth control may be at higher risk, as well as women who use spermicidal agents.

- Menopause. After menopause, a decline in circulating estrogen causes changes in the urinary tract that make you more vulnerable to infection.

Other risk factors for urinary tract infections include:

- Urinary tract abnormalities. Babies born with urinary tract abnormalities that don’t allow urine to leave the body normally or cause urine to back up in the urethra have an increased risk of urinary tract infections.

- Blockages in the urinary tract with incomplete bladder emptying. Kidney stones, an enlarged prostate (prostatic hyperplasia), prostatic carcinoma, urethral stricture, pelvic organ prolapse or foreign body, can trap urine in the bladder and increase the risk of urinary tract infections.

- A suppressed immune system. Diabetes and other diseases that impair the immune system — the body’s defense against germs — can increase the risk of urinary tract infections.

- Catheter use (chronic or intermittent). People who can’t urinate on their own and use a tube (catheter) to urinate have an increased risk of urinary tract infections (catheter-associated UTIs [CAUTIs]). This may include people who are hospitalized, people with neurological problems that make it difficult to control their ability to urinate and people who are paralyzed.

- A recent urinary procedure. Urinary surgery or an exam of your urinary tract that involves medical instruments can both increase your risk of developing a urinary tract infection.

- Urinary incontinence

- Fecal incontinence

- Neurogenic bladder

- Residual urine with ischemia of bladder wall

- Inadequate fluid uptake

- Voiding dysfunction

- Spermicide – increased binding

- Recent antibiotic use – decreased indigenous flora

- Vaginal dysbiosis. Recent studies have also revealed an association between vaginal dysbiosis and increased UTI risk 98. Transient colonization with Gardnerella vaginalis, an organism that is overgrown in patients with bacterial vaginosis, triggered activation of latent uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) reservoirs in a mouse model of infection 99. Gardnerella vaginalis colonization leads to the exfoliation of superficial umbrella cells by inducing apoptosis in the bladder epithelium. These effects were not seen with transient colonization of Lactobacillus crispatus, a normal component of a healthy vaginal microbiota with proven efficacy in reducing the risk of recurrent UTI 100. Additionally, Gardnerella vaginalis causes kidney inflammation in an interleukin-1α (IL-1α)-dependent manner, predisposing colonized animals to uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC)-dependent pyelonephritis 99. Together, these findings provide mechanistic support for previous observations noting the overlap between bacterial vaginosis and pyelonephritis risk factors 101.

Urinary tract infection prevention

Besides prescription antibiotic treatment, if you have repeated urinary tract infections there are some self-help measures that may help prevent further infections.

You can take these steps to reduce your risk of urinary tract infections:

- Drink more fluids especially water to help flush out bacteria to at least 2L/day. Drinking water helps dilute your urine and ensures that you’ll urinate more frequently — allowing bacteria to be flushed from your urinary tract before an infection can begin.

- Drink cranberry juice. Although studies are not conclusive that cranberry juice prevents urinary tract infections, it is likely not harmful.

- Urinate immediately after intercourse. Also, drink a full glass of water to help flush bacteria.

- Gently wipe from front to back after urinating and after a bowel movement helps prevent bacteria in the anal region from spreading to the vagina and urethra.

- Wear cotton underwear and loose fitting pants.

- Avoid potentially irritating feminine products. Using deodorant sprays or other feminine products, such as douches and powders, in the genital area can irritate the urethra.

- Eat natural yogurt to restore normal vaginal environment

- Find an alternative method of birth control if you use spermicides or diaphragm. Diaphragms, or unlubricated or spermicide-treated condoms, can all contribute to bacterial growth.