What is uveitis

Uveitis is a term to describe a group of conditions that cause inflammation of the uvea or the middle layer of the wall of your eye. However, the disease isn’t just limited to the uvea, it can also affect the lens, retina, optic nerve and vitreous. Uveitis can lead to redness, blurred vision and eye pain, and may cause irreversible blindness if left untreated. Uveitis warning signs often come on suddenly and get worse quickly. They include eye redness, pain and blurred vision. The condition can affect one or both eyes. Uveitis primarily affects people ages 20 to 60, but it may also affect children.

- Uveitis is the third leading cause of blindness worldwide.

The uvea is the middle layer of tissue in the wall of the eye. It consists of the iris, the ciliary body and the choroid. The choroid is sandwiched between the retina and the sclera. The retina is located at the inside wall of the eye and the sclera is the outer white part of the eye wall. The uvea provides blood flow to the deep layers of the retina.

Uveitis can last for a short (acute) or a long (chronic) time. The severest forms of uveitis reoccur many times.

Eye care professionals may also describe the disease as infectious or noninfectious uveitis.

The type of uveitis you have depends on which part or parts of the eye are inflamed:

- Iritis (anterior uveitis) affects the front of your eye and is the most common type.

- Cyclitis or pars planitis (intermediate uveitis) affects the ciliary body.

- Choroiditis and retinitis (posterior uveitis) affects the retina and blood vessels at the back of your eye.

- Diffuse uveitis (panuveitis) occurs when all layers of the uvea are inflamed.

In any of these conditions, the jelly-like material in the center of your eye (vitreous) can become inflamed and infiltrated with inflammatory cells.

The most common form of uveitis involves inflammation the front part of the eye. It is often called iritis because it most often only affects the iris. The iris is the colored part of the eye. In most cases, it occurs in healthy people. The disorder may affect only one eye. It is most common in young and middle-aged people.

Posterior uveitis affects the back part of the eye. It involves primarily the choroid. This is the layer of blood vessels and connective tissue in the middle layer of the eye. This type of uveitis is called choroiditis. If the retina is also involved, it is called chorioretinitis.

Another form of uveitis is pars planitis. Pars planitis is the inflammation involving the narrow section of the ciliary body (pars plana) between the colored part of the eye (iris) and the choroid. In association with the inflammation or immunological response, fluid and cells infiltrate the clear gelatin-like substance (vitreous humor) of the eyeball, near the retina and/or pars plana. As a result, swelling of the eye or eyes can also occur, but more importantly blurred vision and progressive increase in the vision of floaters is reported as main symptoms by patients suffering this condition as a result of the infiltration of the vitreous humor. Pars planitis most often occurs in young men. It is generally not associated with any other disease. However, it may be linked to Crohn’s disease and possibly multiple sclerosis. Pars planitis inflammation occurs in the intermediate zone of the eye; that is, between the anterior part(s) of the eye (iris) and the posterior part(s), the retina and/or choroid. It has therefore been designated as one of the diseases of a family of intermediate uveitis.

Possible causes of uveitis are infection, injury, or an autoimmune or inflammatory disease. Many times a cause can’t be identified.

Uveitis can be serious, leading to permanent vision loss. Early diagnosis and treatment are important to prevent the complications of uveitis.

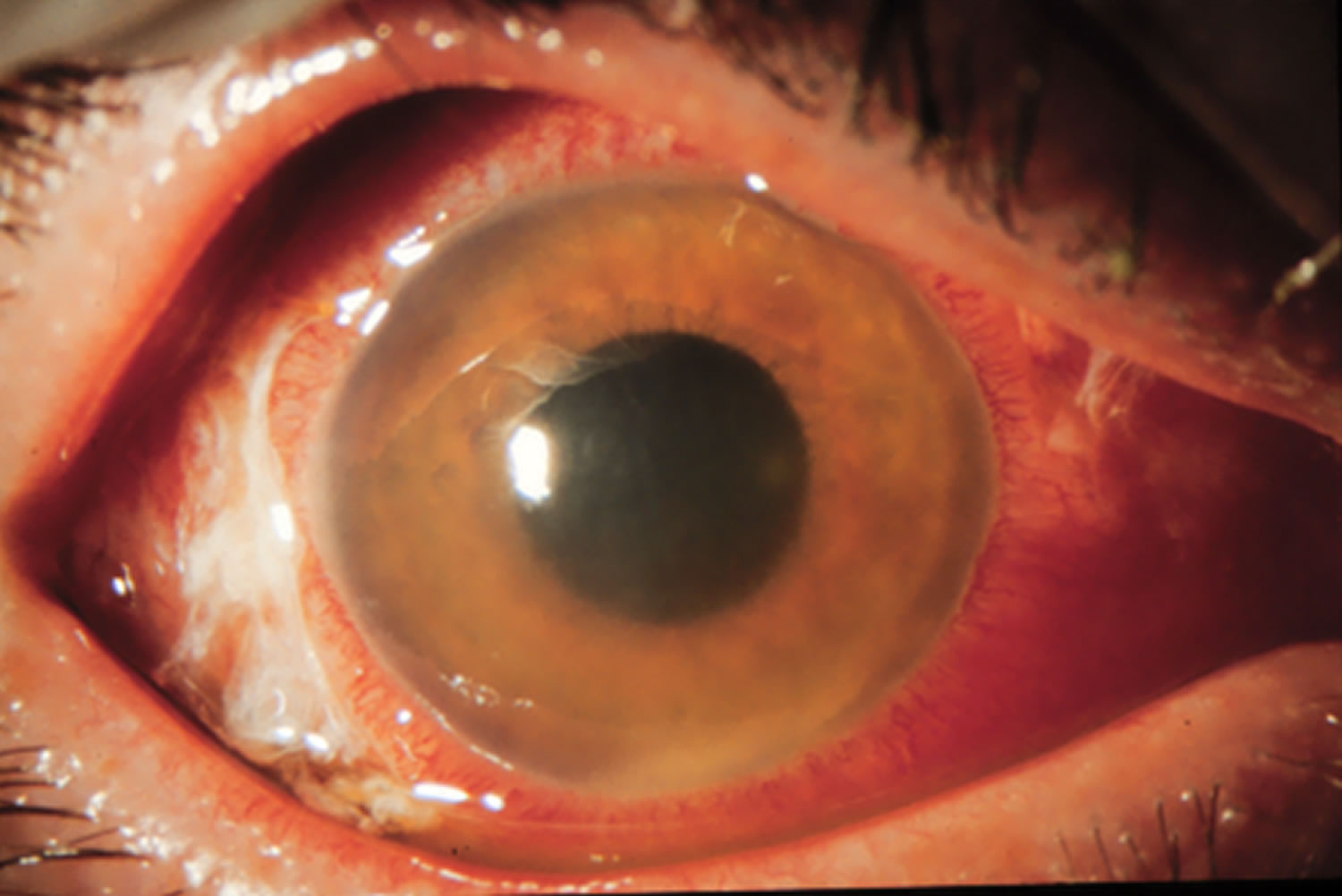

Anterior Uveitis

Anterior uveitis occurs in the front of the eye – when the iris and the ciliary body become inflamed. Anterior uveitis is the most common form of uveitis accounting for 75 percent of cases, predominantly occurring in young and middle-aged people. Many cases occur in healthy people and may only affect one eye but some are associated with rheumatologic, skin, gastrointestinal, lung and infectious diseases.

Intermediate Uveitis

Intermediate uveitis is commonly seen in children, teenagers and young adults. The center of the inflammation often appears in the vitreous. It has been linked to several disorders including, sarcoidosis and multiple sclerosis.

Posterior Uveitis

Posterior uveitis is the least common form of uveitis. It primarily occurs in the back of the eye, often involving both the retina and the choroid. It is often called choroditis or chorioretinitis. There are many infectious and non-infectious causes to posterior uveitis.

Pan-Uveitis

Pan-uveitis is a term used when all three major parts of the eye are affected by inflammation. Behcet’s disease is one of the most well-known forms of pan-uveitis and it greatly damages the retina.

Intermediate, posterior, and pan-uveitis are the most severe and highly recurrent forms of uveitis. They often cause blindness if left untreated.

Eye with uvea

The uvea is the middle layer of the eye which contains much of the eye’s blood vessels (see diagram). This is one way that inflammatory cells can enter the eye. Located between the sclera, the eye’s white outer coat, and the inner layer of the eye, called the retina, the uvea consists of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid:

- Iris: The colored circle at the front of the eye. It defines eye color, secretes nutrients to keep the lens healthy, and controls the amount of light that enters the eye by adjusting the size of the pupil.

- Ciliary Body: It is located between the iris and the choroid. It helps the eye focus by controlling the shape of the lens and it provides nutrients to keep the lens healthy.

- Choroid: A thin, spongy network of blood vessels, which primarily provides nutrients to the retina.

Uveitis disrupts vision by primarily causing problems with the lens, retina, optic nerve, and vitreous.

Lens: Transparent tissue that allows light into the eye.

Retina: The layer of cells on the back, inside part of the eye that converts light into electrical signals sent to the brain.

Optic Nerve: A bundle of nerve fibers that transmits electrical signals from the retina to the brain.

Vitreous: The fluid filled space inside the eye.

Figure 1. Structure of the human eye

Figure 3. Posterior uveitis (toxoplasmosis)

Figure 4. Posterior uveitis (systemic lupus erythematosus)

Uveitis complications

Left untreated, uveitis can cause complications, including:

- Glaucoma

- Cataracts

- Optic nerve damage

- Fluid within the retina

- Irregular pupil

- Retinal detachment

- Permanent vision loss

Uveitis eye prognosis

With proper treatment, most attacks of anterior uveitis go away in a few days to weeks. However, the problem often returns.

Posterior uveitis may last from months to years. It may cause permanent vision damage, even with treatment.

Uveitis causes

In about 50 percent of all cases, the specific cause of uveitis isn’t clear. If a cause can be determined, it may be one of the following:

- Eye injury or surgery

- An autoimmune disorder, such as ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Behcet’s syndrome, Kawasaki disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), psoriasis, reactive arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Vogt Koyanagi Harada’s disease or sarcoidosis

- An inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis

- An infection, such as cat-scratch disease, herpes zoster, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, histoplasmosis, tuberculosis, AIDS, Lyme disease, CMV retinitis (cytomegalovirus) or West Nile virus

- A cancer that affects the eye, such as lymphoma

Uveitis is caused by inflammatory responses inside the eye.

Inflammation is the body’s natural response to tissue damage, germs, or toxins. It produces swelling, redness, heat, and destroys tissues as certain white blood cells rush to the affected part of the body to contain or eliminate the insult.

The reported incidence of ocular manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease is variable, ranging from 0.3% to 13%, 1.6% to 5.4% among those with ulcerative colitis and 3.5% to 6.8% among those with Crohn’s disease 1 and may be primary, secondary to treatment, effects of the intestinal disease or coincidental 2. Ocular complications occur more frequently in patients with Crohn’s disease 3, rather than ulcerative colitis, and an association has been reported with female sex 1. Patients with a colonic or ileocolonic disease location tend to have a higher incidence of ocular involvement compared with those with only a small bowel disease location 4. The presence of other extraintestinal manifestations such as arthralgia in Crohn’s disease has been associated with ocular involvement 5. Although episcleritis, scleritis, and uveitis are the most common ocular-extra-intestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease 2, orbital inflammatory disease has also been reported as a rare extra-intestinal manifestation.

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease is a rare disorder of unknown origin that affects many body systems, including as the eyes, ears, skin, and the covering of the brain and spinal cord (the meninges). The most noticeable symptom is a rapid loss of vision. There may also be neurological signs such as severe headache, vertigo, nausea, and drowsiness. Loss of hearing, and loss of hair (alopecia) and skin color may occur along, with whitening (loss of pigmentation) of the hair and eyelashes (poliosis).

Uveitis may be caused by:

- An attack from the body’s own immune system (autoimmunity).

- Infections or tumors occurring within the eye or in other parts of the body.

- Bruises to the eye.

- Toxins that may penetrate the eye.

Uveitis will cause symptoms, such as decreased vision, pain, light sensitivity, and increased floaters. In many cases the cause is unknown.

Risk factors for uveitis

People with changes in certain genes may be more likely to develop uveitis. In addition, a recent study shows a significant association between uveitis and cigarette smoking.

Uveitis symptoms

Uveitis usually causes a red painful eye. The light hurts your eyes. You might get blurred vision and seeing dark floating spots. It can come on suddenly or slowly, and it can affect one or both eyes.

The signs, symptoms and characteristics of uveitis include:

- Eye redness

- Eye pain

- Light sensitivity (photophobia)

- Blurred vision

- Dark, floating spots in your field of vision (floaters)

- Decreased vision

Symptoms may occur suddenly and get worse quickly, though in some cases, they develop gradually. They may affect one or both eyes.

Anyone suffering eye pain, severe light sensitivity, and any change in vision should immediately be examined by an ophthalmologist.

The signs and symptoms of uveitis depend on the type of inflammation.

Acute anterior uveitis may occur in one or both eyes and in adults is characterized by eye pain, blurred vision, sensitivity to light, a small pupil, and redness.

Intermediate uveitis causes blurred vision and floaters. Usually it is not associated with pain.

Posterior uveitis can produce vision loss. This type of uveitis can only be detected during an eye examination.

Uveitis diagnosis

When you visit an eye specialist (ophthalmologist), he or she will likely conduct a complete eye exam and gather a thorough health history.

Diagnosis of uveitis includes a thorough examination and the recording of the patient’s complete medical history. Laboratory tests may be done to rule out an infection or an autoimmune disorder.

A central nervous system evaluation will often be performed on patients with a subgroup of intermediate uveitis, called pars planitis, to determine whether they have multiple sclerosis which is often associated with pars planitis.

You may also need these tests:

- Blood tests

- An Eye Chart or Visual Acuity Test: This test measures whether a patient’s vision has decreased.

- A Funduscopic Exam: The pupil is widened (dilated) with eye drops and then a light is shown through with an instrument called an ophthalmoscope to noninvasively inspect the back, inside part of the eye.

- Ocular Pressure: An instrument, such a tonometer or a tonopen, measures the pressure inside the eye. Drops that numb the eye may be used for this test.

- A Slit Lamp Exam: A slit lamp noninvasively inspects much of the eye. It can inspect the front and back parts of the eye and some lamps may be equipped with a tonometer to measure eye pressure. A dye called fluorescein, which makes blood vessels easier to see, may be added to the eye during the examination. The dye only temporarily stains the eye.

- Analysis of fluid from the eye

- Photography to evaluate the retinal blood flow (angiography)

- Photography to measure the thickness of the retinal tissue and to determine the presence or absence of fluid in or under the retina.

If the ophthalmologist thinks an underlying condition may be the cause of your uveitis, you may be referred to another doctor for a general medical examination and laboratory tests. Sometimes, it’s difficult to find a specific cause for uveitis. However, your doctor will try to determine whether your uveitis is caused by an infection or another condition.

Uveitis treatment

Uveitis treatments primarily try to eliminate inflammation, alleviate pain, prevent further tissue damage, and restore any loss of vision. Treatments depend on the type of uveitis a patient displays. Some, such as using corticosteroid eye drops and injections around the eye or inside the eye, may exclusively target the eye whereas other treatments, such immunosuppressive agents taken by mouth, may be used when the disease is occurring in both eyes, particularly in the back of both eyes.

An eye care professional will usually prescribe steroidal anti-inflammatory medication that can be taken as eye drops, swallowed as a pill, injected around or into the eye, infused into the blood intravenously, or, released into the eye via a capsule that is surgically implanted inside the eye. Long-term steroid use may produce side effects such as stomach ulcers, osteoporosis (bone thinning), diabetes, cataracts, glaucoma, cardiovascular disease, weight gain, fluid retention, and Cushing’s syndrome. Usually other agents are started if it appears that patients need moderate or high doses of oral steroids for more than 3 months.

Other immunosuppressive agents that are commonly used include medications such as methotrexate, mycophenolate, azathioprine, and cyclosporine. These treatments require regular blood tests to monitor for possible side effects. In some cases, biologic response modifiers (BRM), or biologics, such as, adalimumab, infliximab, daclizumab, abatacept, and rituximab are used. These drugs target specific elements of the immune system. Some of these drugs may increase the risk of having cancer.

Medications

- Drugs that reduce inflammation. Your doctor may first prescribe eyedrops with an anti-inflammatory medication, such as a corticosteroid. If those don’t help, a corticosteroid pill or injection may be the next step.

- Drugs that fight bacteria or viruses. If uveitis is caused by an infection, your doctor may prescribe antibiotics, antiviral medications or other medicines, with or without corticosteroids, to bring the infection under control.

- Drugs that affect the immune system or destroy cells. You may need immunosuppressive or cytotoxic drugs if your uveitis affects both eyes, doesn’t respond well to corticosteroids or becomes severe enough to threaten your vision.

Some of these medications can have serious side effects, such as glaucoma and cataracts. You may need to visit your doctor for follow-up examinations and blood tests every 1 to 3 months.

Surgical and other procedures

- Vitrectomy. Surgery to remove some of the vitreous in your eye (vitrectomy) may be necessary to manage the condition.

- Surgery that implants a device into the eye to provide a slow and sustained release of a medication. For people with difficult-to-treat posterior uveitis, a device that’s implanted in the eye may be an option. This device slowly releases corticosteroid medication into the eye for two to three years. Possible side effects of this treatment include cataracts and glaucoma.

The speed of your recovery depends in part on the type of uveitis you have and the severity of your symptoms. Uveitis that affects the back of your eye (choroiditis) tends to heal more slowly than uveitis in the front of the eye (iritis). Severe inflammation takes longer to clear up than mild inflammation does.

Uveitis can come back. Make an appointment with your doctor if any of your symptoms reappear after successful treatment.

Anterior Uveitis Treatments

Anterior uveitis may be treated by:

- Taking eye drops that dilate the pupil to prevent muscle spasms in the iris and ciliary body (see diagram).

- Taking eye drops containing steroids, such as prednisone, to reduce inflammation.

Intermediate, Posterior, and Pan-Uveitis Treatments

Intermediate, posterior, and pan-uveitis are often treated with injections around the eye, medications given by mouth, or, in some instances, time-release capsules that are surgically implanted inside the eye. Other immunosuppressive agents may be given. A doctor must make sure a patient is not fighting an infection before proceeding with these therapies.

A recent Multicenter Uveitis Treatment Trial (MUST), compared the safety and effectiveness of conventional treatment for these forms of uveitis, which suppresses a patient’s entire immune system, with a new local treatment that exclusively suppressed inflammation in the affected eye. Conventionally-treated patients were initially given high doses of prednisone, a corticosteroid medication, for 1 to 4 weeks which were then reduced gradually to low doses whereas locally-treated patients had a capsule that slowly released fluocinolone, another corticosteroid medication, surgically inserted in their affected eyes. Both treatments improved vision to a similar degree, with patients gaining almost one line on an eye chart. Conventional treatment produced few side effects. In contrast, the implant produced more eye problems, such as abnormally high eye pressure, glaucoma, and cataracts. Although both treatments decreased inflammation in the eye, the implant did so faster and to a greater degree. Nevertheless, visual improvements were similar to those of patients given conventional treatment.

References- Troncosa LL, Biancardi AL, Vierira de, Moraes H, Jr, et al. Ophthalmic manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. W J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5836–5848 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5583569/

- Harbord M, Annese V, Vavricka SR, et al. The first European evidence-based consensus on extra-intestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn’ss Colitis. 2016;10:239–254. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4957476/

- Katsanos A, Asproudis I, Katsanos KH, et al. Orbital and optic nerve complications of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn’ss Colitis. 2013;7:683–693. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23083697

- Ramalho J, Castillo M. Imaging of orbital myositis in Crohn’s’s disease. Clin Imaging. 2008;32:227–229. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18502352

- Hopkins DJ, Horan E, Burton IL, et al. Ocular disorders in a series of 332 patients with Crohn’s’s disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1974;58:732–737 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1215010/pdf/brjopthal00272-0048.pdf