What is a vaginal fistula

A fistula is an abnormal connection between 2 epithelial surfaces. Fistula connects 2 surfaces or lumens. It begins on the offending side and makes its way to an adjacent lumen or surface. It follows the easiest and shortest path to the adjacent organ. Vaginal fistula like other fistulae, is a result of a complication of an underlying disease, surgical procedure or injury. A good understanding of the pathophysiological process helps to assess better, manage, and prevent vaginal fistula. Loss of wall integrity with ongoing inflammatory, infectious, or neoplastic process at the rectum, bladder, urethra, colon or vaginal wall can lead to erosion to the adjacent tissue or organ and establishing the abnormal fistulous connection. When the initial process is reversible or curable, like in diverticulitis, fistulae have a better chance to resolve.

The cause of vaginal fistula, an abnormal hole between the bladder (vesico-vaginal fistula) and/or rectum (recto-vaginal fistula) and the vagina of a woman, is divided into two main categories: obstetric and traumatic.

Histopathologic examination of the tissue involved in the fistula reflects an acute inflammatory reaction besides the original pathology of the causative disease. Acute inflammation is caused by a combination of more than one factor like the primary pathology causing the fistula (diverticular disease, malignancy, Crohn’s, among others), tissue irritation by the flow of intestinal content, and the resulting infection. Other histopathological findings like chronic inflammation from radiation, Crohn’s disease, malignancy, and or injury related necrotic process can be identified depending on the cause of the fistula.

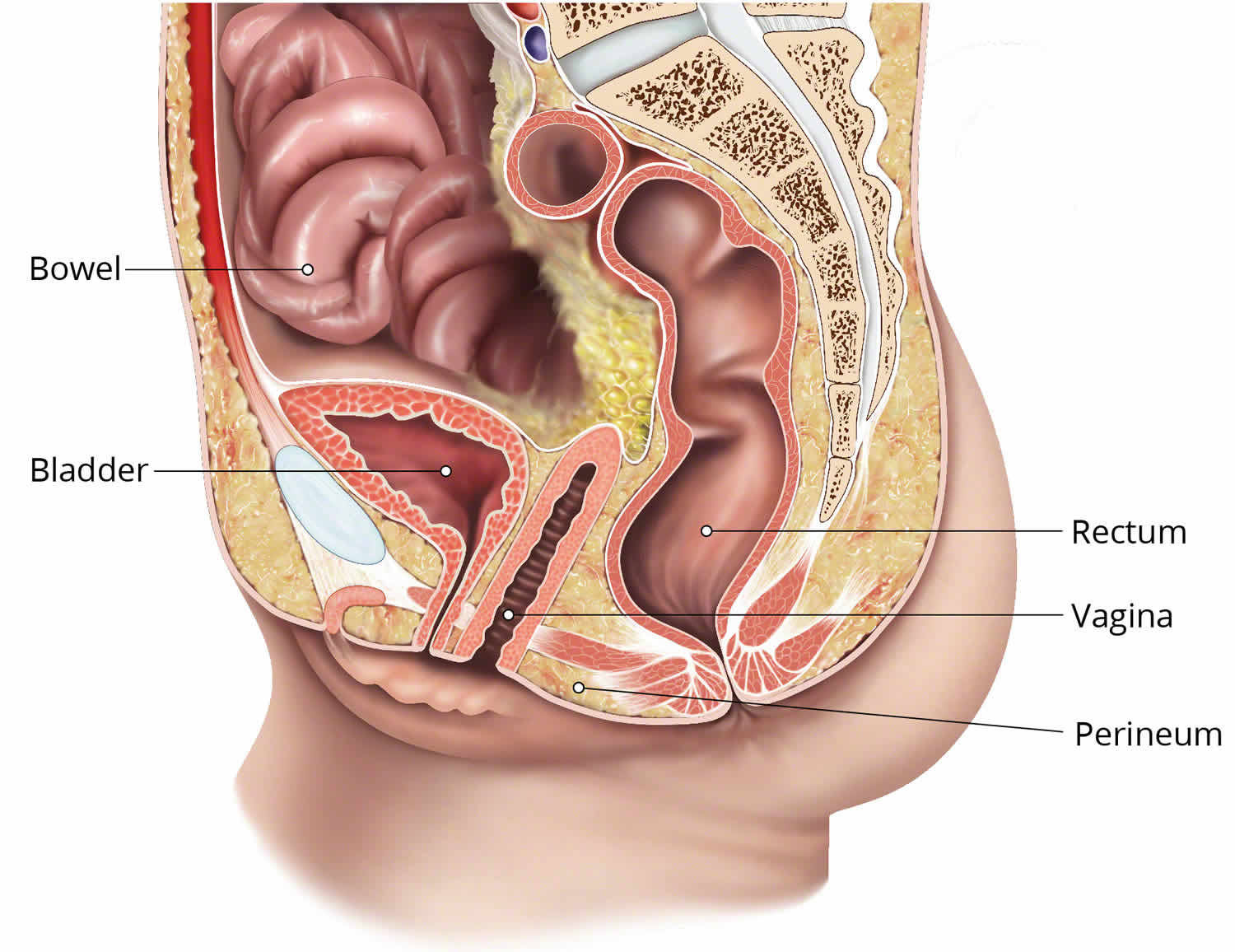

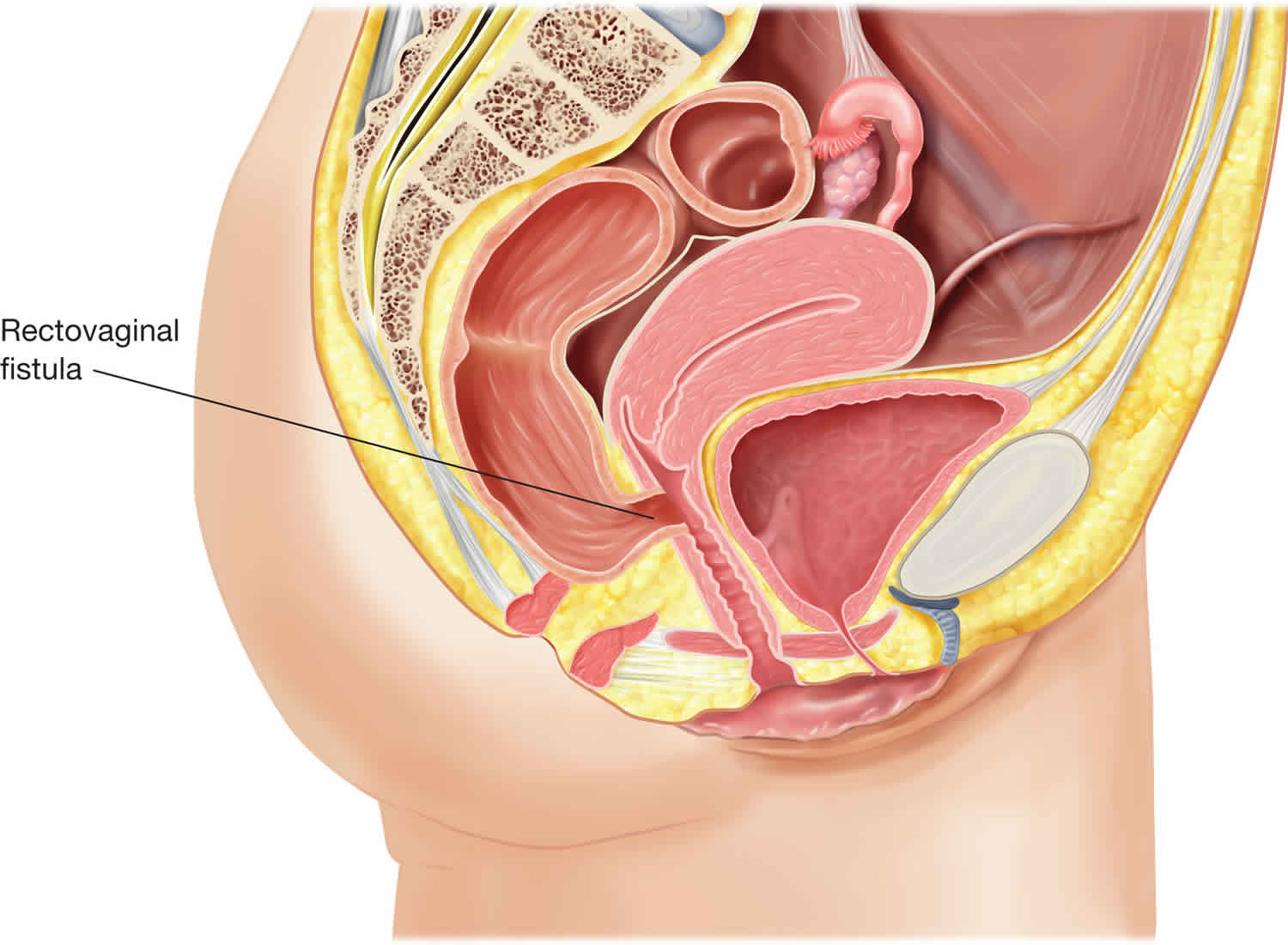

Rectal vaginal fistula

Recto-vaginal fistula starts from the rectum and extends to the vagina. Recto-vaginal fistula is not a healthy situation or physiological status. There is usually an underlying pathology, injury, or surgical event. Characteristics of rectovaginal fistula, for example, site, size, length, activity, and symptoms, vary depending on the cause of the fistula, patient factors, and the treatment received. Recto-vaginal fistula is a potentially challenging surgical condition for both the patient and health care team. The underlying cause determines the method of assessment, management, and prognosis.

The frequency of rectovaginal fistula varies according to the cause. They are typically classified by etiology, location, and size which affects the treatment and prognosis.

Rectovaginal fistulas are divided into 2 groups by location:

- Low rectal vaginal fistulas are located in the lower third of the rectum and the lower half of the vagina. They are closest to the anus and are repaired with a perineal surgical approach.

- High rectal vaginal fistulas are located between the middle third of the rectum and the posterior vaginal fornix. They require a transabdominal surgical repair approach.

- Most rectal vaginal fistulas are less than 2 cm in diameter and are stratified by size:

- Small: Less than 0.5 cm in diameter

- Medium-sized: 0.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter

- Large rectal vaginal fistulas: Exceed 2.5 cm in diameter

Figure 1. Rectovaginal fistula

Rectal vaginal fistula causes

Rectal vaginal fistula formation results as a complication of an underlying disease, injury or surgical event 1. Diseases of the vagina or the pelvic organs can be complicated with a persistent connection between the rectum and vagina. The common causes of rectovaginal fistula are 2:

- Obstetric-related injury: This is the most common etiology of traumatic rectal vaginal fistula, and probably for all rectal vaginal fistulas 3. This includes third- and fourth-degree lacerations during vaginal delivery.

- Surgical procedure: Surgical interventions that cause unrecognized vaginal or rectal injury, insufficient tissue thickness between the two organs, or ischemia of the tissue may result in perforation and fistula formation through the damaged tissue.

- Diverticular disease: Complex diverticular disease is a common cause of fistula connecting to an intra-abdominal organ like the bladder and vagina 4. Erosion of the diverticular wall with inflammation and abscess can extend, involve, and erode the adjacent organ walls resulting in a fistulous connection. An occasional increase in the luminal pressure on either side of the fistula and the continued inflammatory process will maintain the fistula patent.

- Crohn’s disease: Chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, especially Crohn’s disease, is a well-known cause of intestinal fistulization 5. Crohn’s is a transmural disease that involves the entire thickness of the bowl making an extension to and involvement of adjacent tissues and organs very common.

- Malignancy: Cancer of intestine or adjacent organs is a known cause of bowel perforation and fistulization. rectal vaginal fistula can result from vaginal, cervical or more commonly rectal cancer that involves the entire wall thickness and extends to the adjacent vagina. These fistulae are also called malignant fistulae.

- Radiation: Radiation causes long-term chronic tissue inflammation with poor healing and repair processes. Therefore, fistulae caused by radiation manifest after a lag period from the radiation exposure 6.

- Non-surgical injuries and foreign bodies: Injuries in trauma or by a foreign body can result in a non-healing abnormal connection with the vagina.

There are a number of causes that are abbreviated in the mnemonic “FRIEND” (Foreign body, Radiation, Inflammation, Epithelization, Neoplasm, Distal obstruction) 7. These are known causes of non-healing in fistulous diseases. They should not be mixed with the primary or underlying causes of fistula formation.

Rectal vaginal fistula symptoms

The clinical presentation of rectal vaginal fistula is a result of a combination of the passage of rectal content to the vagina, and the underlying disease or injury. A detailed history of the underlying disease should be explored. Clinically, the escape of stool or gas from the rectum to the vagina through the fistula gives the abnormal signs and symptoms of foul-smell vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, passing air, bleeding, and passage of frank stool especially when the patient has diarrhea. Further symptoms of complications like symptoms of cystitis or vaginitis are occasionally encountered. Symptoms of an underlying disease like rectal obstructing cancer or diverticulosis may be present.

Physical exam of the vagina, the source of the symptoms, will likely reveal irritation, erythema, swelling, discharge, stool and possible fistula opening in speculum exam. Office colposcopic exam may reveal more details of the vaginal epithelium and the fistula site as an indurated indentation. A rectovaginal examination may reveal signs of the underlying disease like an obstructing low rectal tumor or phlegmon, Crohn’s disease, or tissue atrophy from radiation.

Rectal vaginal fistula diagnosis

When rectal vaginal fistula is suspected, a workup should be started to confirm the diagnosis, assess the extent of the fistula, and identify the underlying diagnosis. Work up, in addition to history and physical examination, should be complemented by the imaging and endoscopy if needed.

Laboratory tests to assess the baseline hematocrit, biochemical and infectious parameters are usually obtained. Signs of the overall disease impact, complications, and the severity can be estimated from these tests. Further tests may be needed according to the initial assessment.

Endoscopy like colposcopy and/or proctosigmoidoscopy (rigid or preferably flexible) may reveal the site of the fistula with the underlying disease. Signs of the underlying diseases like Crohn’s, diverticular disease, or rectal cancer are likely to be identified with endoscopy. Colposcopy can help detect cervical or vaginal cancers.

Imaging is commonly used and useful to confirm the diagnosis and identify the underlying disease. CT scan provides accurate, objective and detailed information of the fistula, the underlying disease, and the related nearby area. Rectal and intravenous contrast will outline the fistulous tract and the related structures. Presence of rectal contrast in the vagina is a confirmation of the diagnosis even if the fistulous tract itself cannot be visualized.

Further assessment includes laboratory workup to evaluate the general patient condition, underlying disease or complications of the fistula like infection or electrolytes imbalance. Tissue biopsy from suspected masses will help to confirm malignancy and its origin.

Rectal vaginal fistula treatment

Treating rectal vaginal fistula involves treating the underlying disease, the fistula itself and any related complications.[8][9] Therefore, confirming the fistula etiology should be done before planning treatment. Treatment approach depends on many factors like condition severity, acuity, presenting symptoms, patient’s general condition, underlying etiology, and complications resulting from the fistula.[10]

Treatment of Crohn’s disease, diverticular disease or colorectal or gynecologic cancers should follow the principles of treating these diseases primarily. Treating rectal vaginal fistula depends to a great extent on treating the underlying primary disease. There is more than one approach to the treatment of fistula with curative intent. In 2016, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons reviewed the approaches and developed guidelines to manage rectal vaginal fistula.

Medical Treatment

Conservative or non-surgical treatment approach of the symptoms and possible complications like UTI, local irritation, and site infection can be used in selected patients. This approach can be considered in high-risk patients and severe underlying disease. Medical treatment includes treating the infection and the associated symptoms, maximizing medical treatment of the underlying disease like in Crohn’s or diverticulitis, and support of the general patient’s condition. Other conservative treatment includes non-operative measures to close the fistula like fibrin glue or other occlusive measures. The success rate of these measures is not high. They are still an option to consider in high-risk patients who are not fit for surgery or for those who failed a prior surgical approach.

Rectal vaginal fistula surgery

Multiple operative approaches are used to treat rectal vaginal fistula depending on complexity, recurrence, and the underlying disease 8. Simple measures like draining seton in recurrent or acute infection may be used to optimize local tissue integrity and treat the infection.

The proximity of rectal wall to vaginal wall with minimal tissue in between makes repairs connecting fistula challenging. The principles of successful repair are to remove the unhealthy fistula tissue, replace with healthy tissue that has a good blood supply to enhance healing, and maintain thick interposing tissue between the rectal and vaginal walls. Following these principles (although not always possible) increase the chance of successful fistula treatment.

Fistula debridement and flaps are common surgical approaches. Advancement local endo-rectal flaps in simple rectal vaginal fistula or gracilis regional myocutaneous flap in more complicated rectal vaginal fistula are of the common flaps 8.

In proximal or high rectal vaginal fistula, surgical excision of the rectal wall in regimental resection is the other surgical radical approach.

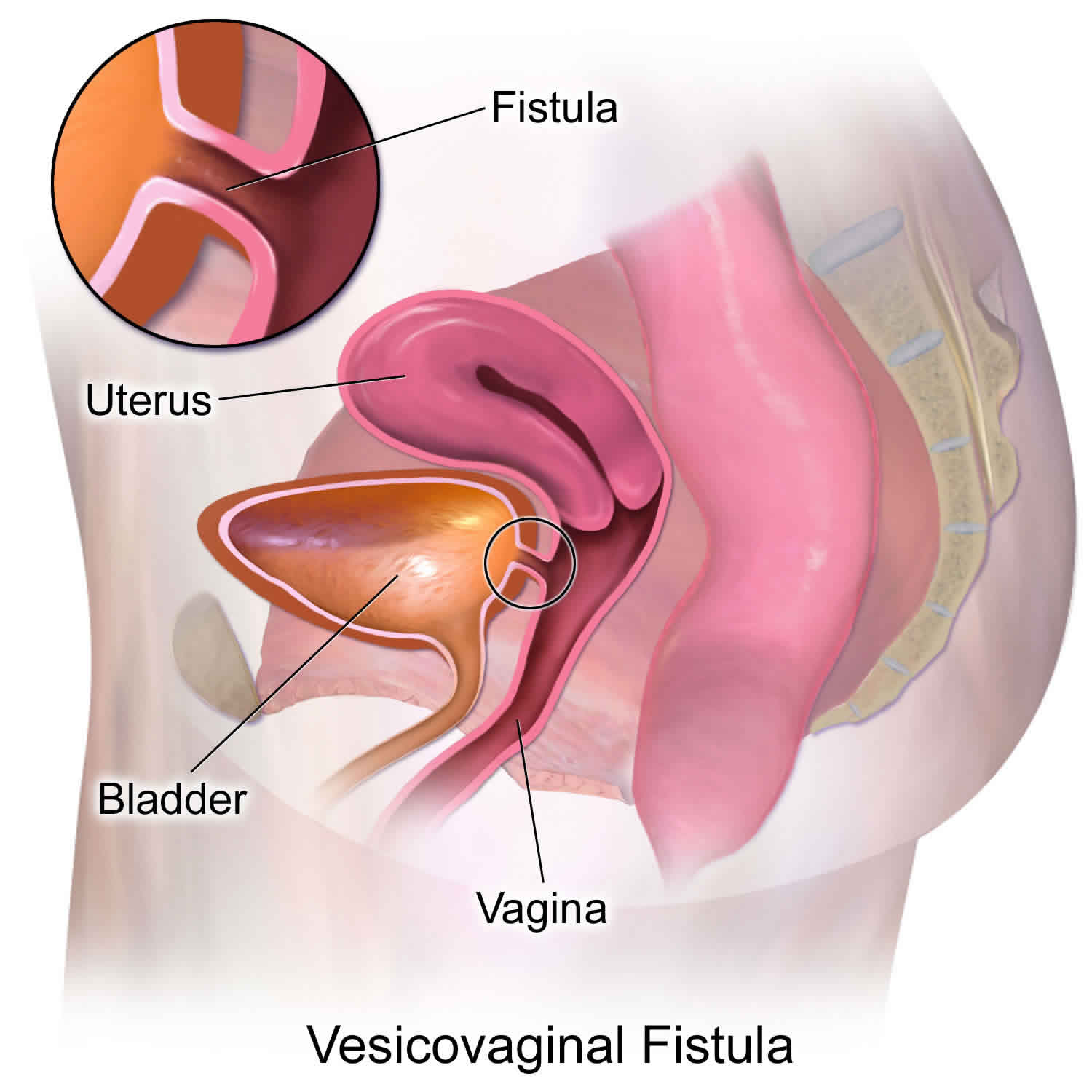

Bladder vaginal fistula

Bladder vaginal fistula also known as vesico-vaginal fistula is an abnormal fistulous tract communicating the urinary bladder with the vagina resulting in continuous urinary leak in to the vagina. Majority of the bladder vaginal fistulas are caused by gynecologic and other pelvic surgical procedures. Birth trauma is still the commonest cause of bladder vaginal fistula in underdeveloped countries with fewer facilities for obstetric care. Significant emotional and social distress accompanies the diagnosis of bladder vaginal fistula and hence requires timely intervention.

In developing countries, the predominant cause of bladder vaginal fistula is prolonged obstructed labor (97%) 9. Bladder vaginal fistulas are associated with marked pressure necrosis, edema, tissue sloughing, and cicatrization. The frequency of bladder vaginal fistula is largely underreported in developing countries.

The magnitude of the bladder vaginal fistula problem worldwide is unknown but believed to be immense 10. In Nigeria alone, Harrison (1985) reported a vesicovaginal fistula rate of 350 cases per 100,000 deliveries at a university teaching hospital. The Nigerian Federal Minister for Women Affairs and Youth Development, Hajiya Aish M.S. Ismail, has estimated that the number of unrepaired bladder vaginal fistulas in Nigeria is between 800,000 and 1,000,000 (2001). In 1991, the World Health Organization identified the following geographic areas where obstetric fistula prevalence is high: virtually all of Africa and south Asia, the less-developed parts of Oceana, Latin America, the Middle East, remote regions of Central Asia, and isolated areas of the former Soviet Union and Soviet-dominated eastern Europe 11.

In contrast to developing countries, countries that practice modern obstetrics have a low rate of urogenital fistulas and bladder vaginal fistula remains the most common type. Less frequently, urogenital fistulas may occur (1) between the bladder and cervix or uterus; (2) between the ureter and vagina, uterus, or cervix; and (3) between the urethra and vagina. Of note, a ureteric injury is identified in association with 10-15% of bladder vaginal fistulas.

The majority of urogenital fistulas in developed countries are a consequence of gynecological surgery. Consequently, the incidence may change as surgical management changes. The incidence of bladder vaginal fistula in the United States is debated. Although most authors quote an incidence rate of bladder vaginal fistula after total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) of 0.5-2%, others suggest only a 0.05% incidence rate of injury to either the bladder or ureter. So if injuries to the bladder and ureters occur in roughly 1% of major gynecologic procedures, and approximately 75% are associated with hysterectomy, and if there are about 500,000 hysterectomies performed each year then about 5,000 women will experience an injury.

Lee, in a series of 35,000 hysterectomies, found more than 80% of genitourinary fistulas arose from gynecological surgery for benign disease. Uncomplicated TAH accounted for more than 70% of these surgeries. The indications for these TAH surgeries excluded the more complex diagnoses, such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), endometriosis, and carcinoma; instead, they were performed primarily for diagnoses such as abnormal bleeding, fibroids, and prolapse. In approximately 10% of cases of bladder vaginal fistula, obstetrical trauma was the associated etiology. Radiotherapy and surgery for malignant gynecologic disease each accounted for 5% of cases.

Notably, a rise in incidence of urogenital fistulas paralleled the switch in policy toward the preference of performing a total hysterectomy over a supracervical hysterectomy.

Figure 2. Bladder vaginal fistula

Bladder vaginal fistula causes

Bladder vaginal fistulas in developed countries are attributed predominantly to inadvertent bladder injury during pelvic surgery (90%). They involve a relatively limited focal bladder injury leading to smaller bladder vaginal fistulas than are observed in developing countries. Numerous authors highlight the risk of various types of bladder trauma during pelvic surgery. Such injuries include unrecognized intraoperative laceration of the bladder, bladder wall injury from electrocautery or mechanical crushing, and the dissection of the bladder into an incorrect plane, causing avascular necrosis.

Suture placement through the bladder wall in itself may not play a significant role in bladder vaginal fistula development. However, the risk of formation of a hematoma or avascular necrosis after a suture is placed through the bladder wall can lead to infection, abscess, and subsequent suture erosion through the bladder wall. This wall defect permits the escape of urine into the vagina and may be followed by an eventual epithelialization of the track.

Gynecologic procedures are the most common iatrogenic factor. Symmonds evaluated 800 genitourinary fistulas over a 30-year period at the Mayo Clinic. Of these, 85% of the bladder vaginal fistulas were related to pelvic operations and 75% were related to hysterectomy, with more than 50% being secondary to simple uncomplicated total abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy. Symmonds also found that 5% of these bladder vaginal fistulas were obstetric and 10% occurred after radiotherapy. Obstetric urogenital fistulas in modern centers include vaginal lacerations from forceps rotations, cesarean delivery, hysterectomy, and ruptured uterus.

Other types of pelvic surgery (eg, urologic, gastrointestinal surgery) also contribute to the incidence of bladder vaginal fistulas; such surgeries include suburethral sling procedures, surgical repair of urethral diverticulum, electrocautery of bladder papilloma, and surgery for pelvic carcinomas. Other less common causes of bladder vaginal fistulas include pelvic infections (eg, tuberculosis, syphilis, lymphogranuloma venereum), vaginal trauma, and vaginal erosion with foreign objects (eg, neglected pessary). Lastly, a congenital urogenital abnormality may exist that includes a bladder vaginal fistula.

Risk factors that predispose to bladder vaginal fistulas include prior pelvic or vaginal surgery, previous pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ischemia, diabetes, arteriosclerosis, carcinoma, endometriosis, anatomic distortion by uterine myomas, and infection, particularly postoperative cuff abscess. Tancer found prior cesarean delivery to be the most common factor predisposing to vault fistula after abdominal surgery in his series of 110 cases; here, 29% were associated with prior cesarean delivery 12. Of interest, Tancer also noted 67% of the bladder vaginal fistulas in his series occurred in the absence of any risk factors. He also noted that 24 patients incurred a bladder injury during hysterectomy; the injury was recognized intraoperatively and received immediate intraoperative repair (often by a consulting specialist). Despite prompt identification, treatment, and postoperative continuous bladder drainage for 7-10 days, a bladder vaginal fistula could not be averted.

Developing countries

Numerous factors contribute to the development of bladder vaginal fistula in developing countries. Commonly, these are areas where the culture encourages marriage and conception at a young age, often before full pelvic growth has been achieved. Chronic malnutrition further limits pelvic dimensions, increasing the risk of cephalopelvic disproportion and malpresentation. In addition, few women are attended by qualified health care professionals or have access to medical facilities during childbirth; their obstructed labor may be protracted for days or weeks 13.

The effect of prolonged impaction of the fetal presenting part in the pelvis is one of widespread tissue edema, hypoxia, necrosis, and sloughing resulting from prolonged pressure on the soft tissues of the vagina, bladder base, and urethra. Typically in these countries, the urogenital fistula is large and involves the bladder, urethra, bladder trigone, and the anterior cervix. Complex neuropathic bladder dysfunction and urethral sphincteric incompetency often result, even if the fistula can be repaired successfully. Other cultural factors that increase the likelihood of obstetrical urogenital fistulas include outlet obstruction due to female circumcision and the practice of harmful traditional medical practices such as Gishiri incisions (anterior vaginal wall incisions) and the insertion of caustic substances into the vagina with the intent to treat a gynecologic condition or to help the vagina to return to its nulliparous state.

Bladder vaginal fistula symptoms

The uncontrolled leakage of urine into the vagina is the hallmark symptom of patients with urogenital fistulas. Patients may complain of urinary incontinence or an increase in vaginal discharge following pelvic surgery or pelvic radiotherapy with or without antecedent surgery. The drainage may be continuous; however, in the presence of a very small urogenital fistula, it may be intermittent. Increased postoperative abdominal, pelvic, or flank pain; prolonged ileus; and fever should alert the physician to possible urinoma or urine ascites and mandates expeditious evaluation. Recurrent cystitis or pyelonephritis, abnormal urinary stream, and hematuria also should initiate a workup for urogenital fistula.

The time from initial insult to clinical presentation depends on the etiology of the bladder vaginal fistula. A bladder vaginal fistula secondary to a bladder laceration typically presents immediately. Approximately 90% of genitourinary fistulas associated with pelvic surgery are symptomatic within 7-30 days postoperatively. An anterior vaginal wall laceration associated with obstetric fistulas typically (75%) presents in the first 24 hours of delivery. In contrast, radiation-induced urogenital fistulas are associated with slowly progressive devascularization necrosis and may present 30 days to 30 years later. Patients with radiation-induced bladder vaginal fistulas initially present with symptoms of radiation cystitis, hematuria, and bladder contracture.

Bladder vaginal fistula diagnosis

Upon examination of the vaginal vault, any fluid collection noted can be tested for urea, creatinine, or potassium concentration to determine the likelihood of a diagnosis of bladder vaginal fistula as opposed to a possible diagnosis of vaginitis.

Indigo carmine dye can be given intravenously and if the dye appears in the vagina, a fistula is confirmed.

Once the diagnosis of urine discharge is made, the physician must identify its source. Cystourethroscopy may be performed, and the fistula(s) may be identified. If ureter involvement is suspected then intravenous pyelogram (IVP) can be performed.

The differential diagnosis for the discharge of urine into the vagina includes single or multiple vesicovaginal, urethrovaginal, or ureterovaginal fistulas and fistula formation between the urinary tract and the cervix, uterus, vagina, vaginal cuff, or (rarely) ureteral fistula to a fallopian tube.

A full vaginal inspection is essential and should include assessment of tissue mobility; accessibility of the fistula to vaginal repair; determination of the degree of tissue inflammation, edema, and infection; and possible association of a rectovaginal fistula.

Urine should be collected for culture and sensitivity, and patients with positive results should be treated prior to surgery.

In patients with a history of local malignancy, a biopsy of the fistula tract and microscopic evaluation of the urine is warranted.

Imaging Studies

Radiologic studies should be employed prior to surgical repair of a bladder vaginal fistula. An intravenous urogram (IVU) is necessary to exclude ureteral injury or fistula because 10% of bladder vaginal fistulas have associated ureteral fistulas. If suspicion is high for a ureteral injury or fistula and the intravenous urogram (IVU) findings are negative, retrograde ureteropyelography should be performed at the time of cystoscopy and examination under anesthesia. A Tratner catheter can be used to assist in evaluation of a urethrovaginal fistula.

Fibrin occlusion therapy is used for the treatment of a variety of fistulas, such as enterocutaneous, anorectal, bronchopleural, ureterocutaneous, and, more recently, bladder vaginal fistulas. Fistulograms are a valuable adjunct to fibrin occlusion therapy.

Diagnostic Procedures

Intraoperative assessment for bladder or ureteral injury may be performed by administering indigo carmine intravenously and closely observing for any subsequent extravasation of dye into the pelvis. Cystourethroscopy to assure bilateral ureteral patency and absence of suture placement in the bladder or urethra has been advocated by some authors as a standard for all pelvic surgery.

Alternatively, intraoperative back-filling of the bladder with methylene blue or sterile milk before completing abdominal or vaginal surgery also may help detect a bladder laceration. Retrograde filling of the bladder also can be used during surgery to better define the bladder base in more difficult dissections.

In the office, the evaluation should include a complete physical examination and detailed review of systems. A cystoscopic examination with a small scope (eg, 19F) may be used to identify bladder vaginal fistula in the bladder or urethra, to determine the number and location and proximity to ureteric orifices, and to identify and remove abnormal entities such as calculi or sutures in the bladder.

In the office, as with the operating room setting, the bladder can be filled with sterile milk or methylene blue in retrograde fashion using a small transurethral catheter. Placement of tampons in tandem in the vaginal vault and observation for staining of the tampons by methylene blue may help to identify and locate fistulas.

Staining of the apical tampon would implicate the vaginal apex or cervix/uterus/fallopian tube; staining of a distal tampon raises suspicion of a urethral fistula. If the tampons are wet but not stained, oral phenazopyridine (Pyridium) or intravenous indigo carmine then can be used to rule out a ureterovaginal, ureterouterine, or ureterocervical fistula. Evidence of staining or wetting of a tampon should then prompt the physician to proceed with additional diagnostic testing prior to proceeding with definitive management.

Water cystoscopy may be inadequate in the face of large or multiple fistulas.

A cystoscopic examination using carbon dioxide gas may be used with the patient in the genupectoral position. With the vagina filled with water or isotonic sodium chloride solution, the infusion of gas through the urethra with a cystoscope produces air bubbles in the vaginal fluid at the site(s) of a urogenital fistula (flat tire sign).

Combined vaginoscopy-cystoscopy may be useful. Andreoni et al describe their technique of simultaneously viewing 2 images on the monitor screen (both cystoscopic and vaginal examinations) 14. They use a laparoscope and clear speculum in the vagina and they use regular cystoscope in the bladder to enhance visualization and identification of bladder vaginal fistulas. Transillumination of the bladder or vagina by turning off the vaginal or bladder light source allows for easier identification of the fistula in the more difficult cases.

Color Doppler ultrasonography with contrast media of the urinary bladder may be considered in cases where cystoscopic evaluation is suboptimal, such as in those patients with severe bladder wall changes like bullous edema or diverticula. Color Doppler ultrasonography demonstrated a bladder vaginal fistula in 92% of the patients studied by Volkmer and colleagues using diluted contrast media and observing jet phenomenon through the bladder wall toward the vagina 15.

Bladder vaginal fistula treatment

Conservative management

If bladder vaginal fistula is diagnosed within the first few days of surgery, a transurethral or suprapubic catheter should be placed and maintained for up to 30 days. Small fistulas (< 1 cm) may resolve or decrease during this period if caution is used to ensure proper continuous drainage of the catheter.

In 1985, Zimmern 16 concluded that if the fistula is small and the patient’s vaginal leakage of urine is cured with Foley placement, the fistula has a high spontaneous cure rate with a 3-week trial of Foley drainage. He also noted that in general, if at the end of 30 days of catheter placement the fistula has diminished in size, a trial of continued catheter drainage for an additional 2-3 weeks may be beneficial. Finally, Zimmern concluded that if no improvement is observed after 30 days, a bladder vaginal fistula is not likely to resolve spontaneously. Under these circumstances, prolonged catheterization only increases the risks of infection and offers no increased benefit to fistula cure.

In their series, Davits and Miranda 17 found complete resolution of 4 bladder vaginal fistulas with continuous bladder drainage maintained for 19-54 days. Tancer 12 noted spontaneous closure in 3 of 151 patients (2%). In these 3 patients, continuous bladder catheterization was provided within 3 weeks of index hysterectomy; none had an epithelialized fistula tract, and 2 had transvesical sutures that were removed at the time of the initial cystoscopic examination. The size of the bladder vaginal fistulas was not documented.

Elkins and Thompson 18 noted some success with continuous bladder drainage. Unfortunately, the rate of success was unpredictable for the individual patient; the rates ranged from 12-80%. Successful cases were characterized by the following criteria: continuous bladder drainage for up to 4 weeks, the bladder vaginal fistulas were diagnosed and treated within 7 days of index surgery, bladder vaginal fistulas were less than 1 cm, and they were not associated with carcinoma or radiation.

Medications

Estrogen replacement therapy in the postmenopausal patient may assist with optimizing tissue vascularization and healing. Oral hormone replacement therapy/estrogen replacement therapy (HRT/ERT) alone has been found to suboptimally estrogenize urogenital tissue in 40% of patients. Treatment with estrogen vaginal cream is recommended for patients with bladder vaginal fistulas who are hypoestrogenic. A 4- to 6-week treatment regimen prior to surgery is commonly recommended. It may be used alone or in combination with oral hormone replacement therapy/estrogen replacement therapy. Dosages range from 2-4 g placed vaginally at bedtime once per week. Alternatively, the patient may place 1 g vaginally at bedtime 3 times per week.

Corticosteroid and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy is theorized to minimize early inflammatory changes at the fistula site. However, its efficacy has not been proven. Because it also carries potential risks for impairment of wound healing, when early repair is planned, cortisone is not recommended for the treatment of bladder vaginal fistula.

Acidification of urine to diminish risks of cystitis, mucus production, and formation of bladder calculi may be a consideration, particularly in the interval between the diagnosis and surgical repair of bladder vaginal fistula. Vitamin C at 500 mg orally 3 times per day may be used to acidify urine. Alternatively, methenamine mandelate at 550 mg plus sodium acid phosphate at 500 mg 1-4 times per day also can be administered to achieve urine acidification.

Urised is effective for control of postoperative bladder spasms. It is a combination of antiseptics (methenamine, methylene blue, phenyl salicylate, benzoic acid) and parasympatholytics (atropine sulfate, hyoscyamine sulfate).

Sitz baths and barrier ointments, such as zinc oxide preparations, can provide needed relief from local ammoniacal dermatitis.

Bladder vaginal fistula surgery

Guidelines to follow intraoperatively to minimize bladder vaginal fistula formation are identical to those followed at the time of index surgery to prevent a fistula complication. A summary of these guidelines follows 19.

Adequate exposure of the operative field should be obtained to avoid inadvertent organ injury and to ensure prompt identification of any injury incurred.

Minimize bleeding and hematoma formation. The closure of dead space at the anterior vaginal wall upon completion of an anterior colporrhaphy will prevent hematoma formation. This technique employs intermittently incorporating pubocervicovaginal fascia with the vaginal mucosal layer as the vaginal wall is sutured.

Widely mobilize the bladder from the vagina during hysterectomy to diminish the risk of suture placement into the bladder wall. A minimum of a 1- to 2-cm margin of dissection of the bladder from the vaginal cuff should be developed prior to cuff closure.

Dissect the pubocervicovaginal endopelvic fascia between the vagina and the bladder in the appropriate plane. Dissection may be easier with a sharp technique compared to a blunt technique; the key is to prevent trauma and separation of bladder wall fibers as the bladder is mobilized off the anterior vaginal wall. The principle of traction and countertraction of the bladder and uterus works well to effect a bloodless dissection at the areolar pubocervicovaginal fascial plane.

If scarring is present at the pubocervicovaginal fascia and dissection is difficult, consider performing an intentional anterior extraperitoneal cystotomy. This technique enables the surgeon to assess the anatomic boundaries of the bladder wall with digital palpation. If scarring is present at the pubocervicovaginal fascia and dissection is difficult, consider employing an intrafascial technique of hysterectomy to best dissect the endopelvic fascial plane.

Intraoperative retrograde filling and emptying of the bladder or mild traction on a temporarily placed small Foley catheter inserted into the fistula itself are helpful to optimally identify anatomical planes and reveal intraoperative bladder lacerations.

Consider supracervical abdominal hysterectomy instead of total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH). The incidence of urogenital fistula formation is lower for supracervical versus total hysterectomy.

If an intraoperative bladder injury does occur, Tancer argues strongly for widely mobilizing the bladder from the underlying structures (fascia and vagina, cervix, or uterus). In doing so, the surgeon can effect a bladder vaginal fistula closure under no tension.

For repairing a cystotomy at the trigonal area, a transverse closure is preferable over a vertical one. Vertical closure would be more likely to produce ureteral obstruction because the ureteral orifices would be drawn inward toward each other. Ureteral catheters should be considered in repair of a cystotomy involving or encroaching on ureteric orifices.

Consider performing cystourethroscopy when performing pelvic surgery. Cystourethroscopy to assure bilateral ureteral patency and the absence of suture placement in the bladder or the urethra has been advocated by some authors as a standard for all pelvic surgery.

Timing of repair

The occurrence of a urogenital fistula is an anguishing experience for both the patient and the surgeon. The timing of repair should be dictated by the overall medical condition of the patient and the tissue quality surrounding the fistula. While the emotional status of the patient should not be underestimated, it also should not play a dominant role in the decision process of when to repair a bladder vaginal fistula.

Controversy surrounds the length of delay between diagnosis and surgical repair of a noninfected bladder vaginal fistula in a patient who has not undergone radiation treatment. Complicating the analysis of data is the fact that no definition has been established for “early” and “late” intervals. Traditionally, late referred to waiting for an 8- to 12-week interval between index surgery and repair. Longer intervals are universally accepted as the standard of care in infected or irradiated tissue. A 1-year interval for radiation-induced fistulas is recommended to ensure full resolution of tissue necrosis.

Margolis and Mercer 20 simply recommend delaying surgery until inflamed and infected tissue has been treated and the infection and inflammation have resolved. O’Conor 21 agrees that the exact timing for repair depends on when the tissue health is adequate; most of his patients were brought to surgery approximately 3 months after index surgery. During the waiting period, he discouraged indwelling catheter usage and generally advocated vaginal estrogen therapy. Consideration to adjunctive steroid therapy may be contemplated.

Carr and Webster 22 suggest a strategy of examining the fistula at 2-week intervals and proceeding to surgery when the tissue is pliable, not infected, and not inflamed. In their experience, this typically occurred 4-8 weeks after index surgery.

In Persky’s series of 7 patients 23, a 100% success rate was noted with repair performed between 1 and 10 weeks. All of these patients had an interposition graft of peritoneum and omentum placed.

In a retrospective analysis of 25 patients with bladder vaginal fistula referred between 1970 and 1980, Blandy and colleagues 24 noted success with all early and late repairs. Only 12 patients were referred before 6 weeks and, therefore, were candidates for early repair. The remaining 13 were referred after 6 weeks. The surgical technique used in all cases was midline cystotomy to the level of the fistula, ureteral catheterization, bladder mobilization from vagina, closure of the vaginal defect with 3-0 chromic catgut in interrupted fashion, and placement of an omental interposition graft. Urethral catheterization was used for 10-12 days. A suprapubic catheter also was placed in approximately half of the patients. Ureteral stents were removed after 5-10 days.

Blaivas 25 documented his philosophy “to repair fistulas as soon as possible and, preferably, by a vaginal approach” in his 1995 article that examined the repair of 24 bladder vaginal fistulas between 1989 and 1993. Early repairs were defined as those that occurred within 12 weeks of index surgery. Success rates for early repair were similar to those for late repair as long as general principles of surgery were followed. He concluded that no benefit was noted by delaying surgery once evidence of any inflammation, induration, or infection was resolved.

Lee 26 found a correlation between increased surgical failure and bladder vaginal fistula repair performed very early (10-15 days). In his experience, a delay of 8-12 weeks from index surgery or failed repair ensures a full resolution of inflammation and edema and provides an adequate blood supply, thereby optimizing success of bladder vaginal fistula repair. However, he exempts certain cases from this general rule. These include fistulas diagnosed within hours of surgery and obstetrical lacerations.

Contraindications to early closure of fistulas, as per Huang et al 27, include multiple unsuccessful closures in the past, an associated enteric fistula with pelvic phlegmon, or previous radiation. These types of fistulas require a delay in their repair of a minimum of 4-8 months and should include usage of an interposing flap/buttress.

Techniques of repair

The best chance for a surgeon to achieve successful repair is by using the type of surgery with which he or she is most familiar. Techniques of repair include (1) the vaginal approach, (2) the abdominal approach, (3) electrocautery, (4), fibrin glue, (5) endoscopic closure using fibrin glue with or without adding bovine collagen, (6) the laparoscopic approach, and (7) using interposition flaps or grafts 28.

The literature documents excellent success rates for both the vaginal and abdominal approaches if the following general surgical principles are followed: (1) complete preoperative diagnosis, (2) exposure, (3) hemostasis, (4) mobilization of tissue, (5) tissue closure under no tension, (6) watertight closure of bladder with any cystotomy repair, (7) timing to avoid infection and inflammation of tissue, (8) adequate blood supply at area of repair, and (9) continuous catheter drainage postoperatively.

The fistula tract excision debate

In their experiences, Raz 29, Vasavada, and Margolis and Mercer 20 note that routine excision of the fistula tract is not mandatory. They emphasize the risks of increasing the size of the fistula tract with attempts to resect it. Additionally, these surgeons contend that the fibrous ring of the fistula may add to the strength of the repair and prevent postoperative bladder spasms. Cruikshank reported a 100% success rate in his series of 11 patients with fistula repair without tract excision 30. Elkins and Thompson 18 state that a small fistula may be resected, but large tracts should only be freshened. They warn of the risk of overexcising fistula edges, thereby causing an increase in the size of the fistula. They point out further risks of intracystic bleeding and blood clot formation from the mucosal edge of the bladder with fistula resection. Subsequent blockage of the catheter postoperatively would then increase the risk of failure of the bladder vaginal fistula repair.

However, Iselin and colleagues 31 strongly feel excision of the fistula tract ensures closure of all layers with viable tissue, thereby optimizing wound healing. In their series of 20 patients who had undergone hysterectomy, a 100% cure rate was obtained with full excision of the fistula tract. They emphasize lack of complications, such as symptomatic vaginal shortening, with their technique.

De-epithelialization of the fistula tract can be accomplished by various techniques. Screw curette is one method. In 1977, Aycinena 32 described the use of a common type of screw to strip away or curet the epithelial lining of small bladder vaginal fistulas. He then simply allowed spontaneous healing to occur. Seven patients were reported in this series, all of whom were treated successfully. Experts in the field caution that this procedure is efficacious only in the smallest of bladder vaginal fistulas. Other methods used to de-epithelialize the fistula tract include electrocoagulation and sharp knife dissection.

References- Thubert T, Cardaillac C, Fritel X, Winer N, Dochez V. [Definition, epidemiology and risk factors of obstetric anal sphincter injuries: CNGOF Perineal Prevention and Protection in Obstetrics Guidelines]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2018 Dec;46(12):913-921

- Bhama AR, Schlussel AT. Evaluation and Management of Rectovaginal Fistulas. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2018 Jan;61(1):21-24

- Mocumbi S, Hanson C, Högberg U, Boene H, von Dadelszen P, Bergström A, Munguambe K, Sevene E., CLIP working group. Obstetric fistulae in southern Mozambique: incidence, obstetric characteristics and treatment. Reprod Health. 2017 Nov 10;14(1):147

- Bahadursingh AM, Longo WE. Colovaginal fistulas. Etiology and management. J Reprod Med. 2003 Jul;48(7):489-95.

- Sheedy SP, Bruining DH, Dozois EJ, Faubion WA, Fletcher JG. MR Imaging of Perianal Crohn Disease. Radiology. 2017 Mar;282(3):628-645.

- Iwamuro M, Hasegawa K, Hanayama Y, Kataoka H, Tanaka T, Kondo Y, Otsuka F. Enterovaginal and colovesical fistulas as late complications of pelvic radiotherapy. J Gen Fam Med. 2018 Sep;19(5):166-169.

- Tuma F, Waheed A, Al-Wahab Z. Rectovaginal Fistula. [Updated 2019 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535350

- Rottoli M, Vallicelli C, Boschi L, Cipriani R, Poggioli G. Gracilis muscle transposition for the treatment of recurrent rectovaginal and pouch-vaginal fistula: is Crohn’s disease a risk factor for failure? A prospective cohort study. Updates Surg. 2018 Dec;70(4):485-490.

- Vesicovaginal Fistula. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/267943-overview

- Maheu-Giroux M, Filippi V, Maulet N, et al. Risk factors for vaginal fistula symptoms in Sub-Saharan Africa: a pooled analysis of national household survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:82. Published 2016 Apr 21. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0871-6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4839076

- Tebeu PM, Fomulu JN, Khaddaj S, de Bernis L, Delvaux T, Rochat CH. Risk factors for obstetric fistula: a clinical review. Int Urogynecol J. 2011 Dec 6.

- Tancer ML. Observations on prevention and management of vesicovaginal fistula after total hysterectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992 Dec. 175(6):501-6.

- Capes T, Ascher-Walsh C, Abdoulaye I, Brodman M. Obstetric fistula in low and middle income countries. Mt Sinai J Med. 2011 May-Jun. 78(3):352-61.

- Andreoni C, Bruschini H, Truzzi JC, Simonetti R, Srougi M. Combined vaginoscopy-cystoscopy: a novel simultaneous approach improving vesicovaginal fistula evaluation. J Urol. 2003 Dec. 170(6 Pt 1):2330-2.

- Volkmer BG, Kuefer R, Nesslauer T, Loeffler M, Gottfried HW. Colour Doppler ultrasound in vesicovaginal fistulas. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2000 Jun. 26(5):771-5.

- Zimmern PE, Hadley HR, Staskin D. Genitourinary fistulas: vaginal approach for repair of vesicovaginal fistulas. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1985 Jun. 12(2):403-13.

- Davits RJ, Miranda SI. Conservative treatment of vesicovaginal fistulas by bladder drainage alone. Br J Urol. 1991 Aug. 68(2):155-6.

- Elkins T, Thompson J. Lower urinary tract fistulas. Walters M, Karram M, eds. Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1999. 355-66.

- Angioli R, Penalver M, Muzii L, Mendez L, Mirhashemi R, Bellati F. Guidelines of how to manage vesicovaginal fistula. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003 Dec. 48(3):295-304.

- Margolis T, Mercer LJ. Vesicovaginal fistula. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994 Dec. 49(12):840-7.

- O’Conor VJ Jr. Review of experience with vesicovaginal fistula repair. J Urol. 1980 Mar. 123(3):367-9.

- Carr LK, Webster GD. Abdominal repair of vesicovaginal fistula. Urology. 1996 Jul. 48(1):10-1.

- Persky L, Herman G, Guerrier K. Nondelay in vesicovaginal fistula repair. Urology. 1979 Mar. 13(3):273-5.

- Blandy JP, Badenoch DF, Fowler CG. Early repair of iatrogenic injury to the ureter or bladder after gynecological surgery. J Urol. 1991 Sep. 146(3):761-5.

- Blaivas JG, Heritz DM, Romanzi LJ. Early versus late repair of vesicovaginal fistulas: vaginal and abdominal approaches. J Urol. 1995 Apr. 153(4):1110-2; discussion 1112-3.

- Lee RA, Symmonds RE, Williams TJ. Current status of genitourinary fistula. Obstet Gynecol. 1988 Sep. 72(3 Pt 1):313-9.

- Huang WC, Zinman LN, Bihrle W 3rd. Surgical repair of vesicovaginal fistulas. Urol Clin North Am. 2002 Aug. 29(3):709-23.

- Abdel-Karim AM, Moussa A, Elsalmy S. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery extravesical repair of vesicovaginal fistula: early experience. Urology. 2011 Sep. 78(3):567-71

- Raz S. Female Urology. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1893. 373-7.

- Cruikshank SH. Early closure of posthysterectomy vesicovaginal fistulas. South Med J. 1988 Dec. 81(12):1525-8.

- Iselin CE, Aslan P, Webster GD. Transvaginal repair of vesicovaginal fistulas after hysterectomy by vaginal cuff excision. J Urol. 1998 Sep. 160(3 Pt 1):728-30.

- Aycinena JF. Small vesicovaginal fistula. Urology. 1977 May. 9(5):543-5.