Vesicointestinal fistula

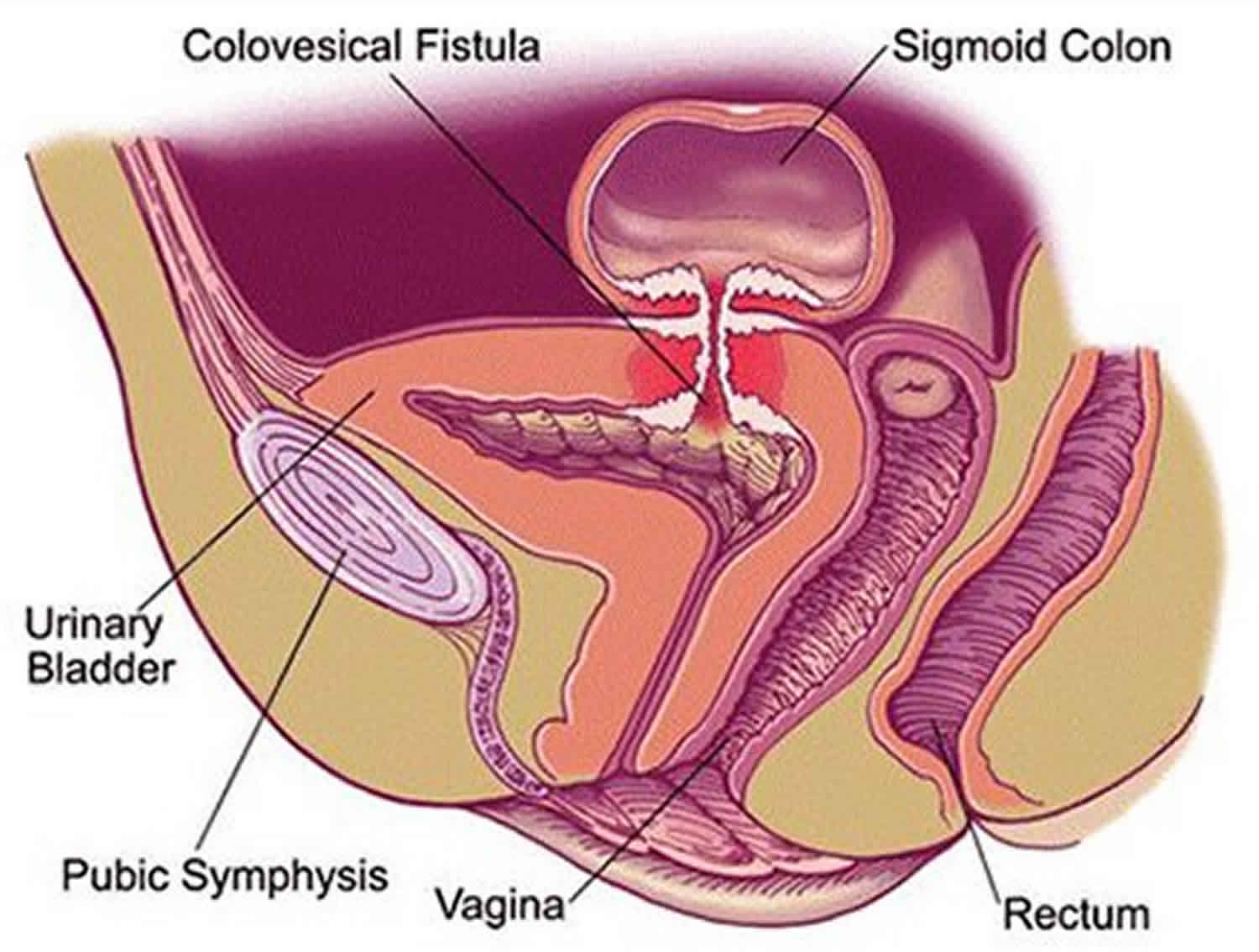

Vesicointestinal fistula also known as enterovesical fistula or intestinovesical fistula, is a fistula (a communication between the lumen of the colon and that of the urinary bladder) that forms between the bladder and the bowel, either directly or via an intervening abscess cavity (foyer intermediaire).

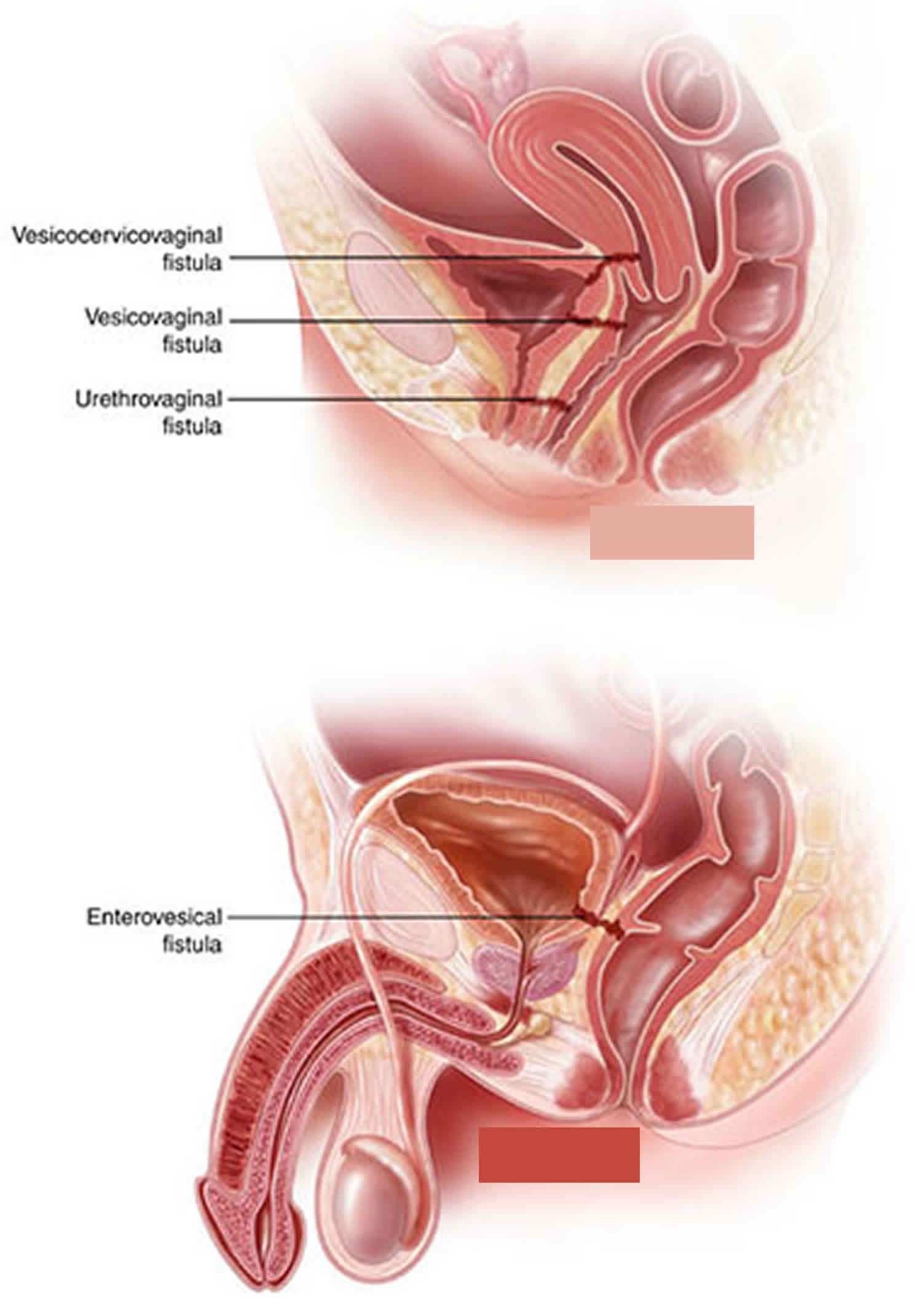

A fistula involving the bladder can have one of many specific names, describing the specific location of its outlet:

- Bladder and intestine: “vesicoenteric”, “enterovesical”, or “vesicointestinal” fistula

- Bladder and colon: “vesicocolic” or “colovesical” fistula

- Bladder and rectum: “vesicorectal” or “rectovesical” fistula

Colovesical fistula is the most common form of vesicointestinal fistula and is most often located between the sigmoid colon and the dome of the bladder. When the communication is between the rectum and urinary bladder, the term rectovesical fistula is used. Rectourethral and rectovesical fistulae are observed in the postoperative setting, such as after prostatectomy, as a consequence of chronic infection or tissue destruction that accompanies massive decubiti, or in the setting of acute infections such as Fournier gangrene 1.

In most cases, the colovesical fistula occurs through the dome of the bladder (~ 60%). The posterior wall (~ 30%) and trigone (~ 10%) are less frequent sites 2.

Normally, the urinary system is completely separated from the alimentary canal. Connections may result from any of the following:

- Incomplete separation of the two systems during embryonic development (eg, failure of the urorectal septum to divide the common cloaca)

- Infection

- Inflammatory conditions

- Cancer

- Trauma or foreign body

- Iatrogenic causes (presenting either postoperatively or as a treatment complication)

Colovesical fistulas and its cause can be characterized in a number of ways, although the fistulous tract itself is often difficult to demonstrate.

In most instances, colovesical fistula diagnosis is suspected clinically due to pneumaturia (bubbles in the urine), faecaluria (feces in the urine), recurrent urinary tract infections, or passage of urine rectally 3. In some cases, colovesical fistula will be first diagnosed radiologically at the time of investigation for the primary disease.

Surgical resection of the colovesical fistula and abnormal segment of bowel is usually required for cure, although in the setting of cancer this suggests advanced disease (T4) making surgery complex. In such cases, if palliation only is required then defunctioning colostomy, colonic stent placement or a nephrostomy may be required 4.

Vesicointestinal fistula causes

Diverticulitis is the most common cause of vesicointestinal fistula, arising in 60% of such cases 5.

Other causes include 5:

- Carcinoma of the bladder invading the colon

- Carcinoma of the colon invading the bladder – colorectal cancer ~ 20%

- Crohn disease ~ 10%

- Radiation bowel injury

- External trauma

- Foreign bodies

- Appendicitis.

Vesicointestinal fistulas are rare medical findings and mostly represent complications of diverticulitis, cancer, or Crohn’s disease 6. Advanced tumors, which grow abundantly in the abdominal or pelvic cavity, are responsible for approximately 20%-30% of vesicointestinal fistulas 7. Most frequently, vesicointestinal fistulas originate from colon adenocarcinomas but may also occur as a consequence of neoplasms in other pelvic organs 8. In any case, vesicointestinal fistulas are observed at very advanced stages of neoplastic diseases 9. Congenital colovesical fistulas are rare and are often associated with an imperforate anus.

Inflammatory vesicointestinal fistula

Diverticulitis accounts for approximately 50%-70% of vesicoenteric fistulae, almost all of which are vesicointestinal fistulas. A phlegmon or abscess is a risk factor for fistula formation 10. This complication occurs in 2%-4% of cases of diverticulitis, although referral centers have reported a higher incidence 11.

Crohn disease accounts for approximately 10% of vesicointestinal fistulas and is the most common cause of an ileovesical fistula. Ileovesical fistulae develop in 10% of patients with regional ileitis. The transmural nature of the inflammation characteristic of Crohn colitis often results in adherence to other organs. Subsequent erosion into adjacent organs can then give rise to a fistula. The mean duration of Crohn disease at the time of first symptoms of fistula formation is 10 years, and the average patient age is 30 years 12.

Less-common inflammatory causes of vesicointestinal fistulas include Meckel diverticulum 13, genitourinary coccidioidomycosis 14 and pelvic actinomycosis 15. In addition, case reports have described appendicovesical fistulae as a complication of appendicitis 16. Enterovesical fistula formation due to lymphadenopathy associated with Fabry disease has been reported 17.

Rarely, the inflammatory process originates in the bladder, as noted in a case report from Spain of bladder gangrene that caused a vesicointestinal fistula in a patient with diabetes mellitus 18. Other case reports have demonstrated fistula formation in the setting of chronic outlet obstruction due to benign prostatic hypertrophy, with the formation of a large bladder stone and recurrent infections 19.

Malignant vesicointestinal fistula

Malignancy accounts for up to 20% of vesicointestinal fistulas and is the second most common cause of enterovesical fistula. Rectovesical fistula is the most common presentation, as rectal carcinoma is the most common colonic malignancy resulting in fistula formation 20. Transmural carcinomas of the colon and rectum may adhere to adjacent organs and may eventually invade directly, causing development of a fistula. Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder is the next most common malignancy-related pathology 21. Occasionally, carcinomas of the cervix, prostate, and ovary are implicated, and incidents involving small-bowel lymphoma have been reported 22.

Although cancer is the second most common cause of enterovesical fistula formation, such cases have become uncommon because most carcinomas are diagnosed and treated prior to this advanced stage.

Iatrogenic vesicointestinal fistula

Iatrogenic fistulae are usually induced by surgical procedures, primary or adjunctive radiotherapy, and/or postprocedural infection. Surgical procedures, including prostatectomies, resections of benign or malignant rectal lesions, and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, are well-documented causes of rectovesical and rectourethral fistulae 23. Unrecognized rectal injury at the time of radical prostatectomy is an uncommon but well-documented etiology of rectourethral fistula.

External beam radiation or brachytherapy to bowel in the treatment field can eventually lead to fistula development. Radiation-associated fistulae usually develop years after radiation therapy for a gynecologic or urologic malignancy. The incidence of radiation-induced fistula associated with gynecological cancers (most commonly cervical cancer) is approximately 1%, many of which are rectovaginal or vesicovaginal 24.

Fistulae develop spontaneously after perforation of the irradiated intestine, with the development of an abscess in the pelvis that subsequently drains into the adjacent bladder. Radiation-associated fistulae are usually complex and often involve more than one organ (eg, colon to bladder). Because of improvements in radiotherapy techniques, the incidence of this complication is decreasing.

Although rare, fistulae due to cytotoxic therapy have been reported. One case involved a patient undergoing a CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) regimen for non-Hodgkin lymphoma 25. Another involved enterovesical fistula as a result of neutropenic enterocolitis (a complication of chemotherapy) in a pediatric patient with acute leukemia 26.

Traumatic vesicointestinal fistula

Urethral disruption caused by blunt trauma or a penetrating injury can result in fistulae, but these fistulae are typically rectourethral in nature. Penetrating abdominal or pelvic trauma, such as a gunshot wound, may result in fistula formation between both small and large bowel, including the rectum with the bladder. In a recent review of complications of penetrating rectal and bladder injuries, fistula formation occurred only in the presence of bowel and bladder injuries 27. Foreign bodies in the bowel (eg, swallowed chicken bones or toothpicks) and peritoneum (eg, lost gallstone during laparoscopic cholecystectomy) have been reported as a cause of vesicointestinal fistulae 28.

Vesicointestinal fistula symptoms

The patient may be asymptomatic. More commonly, patient’s present with 29:

- Fecaluria – mixture of feces and urine that is passed from the urethra

- Pneumaturia – air bubbles that pass in your urine

- Passage of urine rectally

- Refractory urinary tract infection

In some cases, it will be first diagnosed radiologically at the time of investigation for the primary disease.

On examination, a pelvic mass be palpable.

The hallmark of enterovesical fistulas may be described as Gouverneur syndrome, namely, suprapubic pain, frequency, dysuria, and tenesmus. Other signs include abnormal urinalysis findings, malodorous urine, pneumaturia, debris in the urine, hematuria, and UTIs (urinary tract infections) 30.

The severity of the presentation also varies. Chronic urinary tract infection symptoms are common, and patients with enterovesical fistula frequently report numerous courses of antibiotics prior to referral to a urologist for evaluation. Urosepsis may be present and can be exacerbated in the setting of obstruction. It has been demonstrated in dog models that surgically created colovesical fistulae are tolerated well in the absence of obstruction 31.

Pneumaturia and fecaluria may be intermittent and must be carefully sought in the history. Pneumaturia occurs in approximately 50%-60% of patients with enterovesical fistula but alone is nondiagnostic, as it can be caused by gas-producing organisms (eg, Clostridium species, yeast) in the bladder, particularly in patients with diabetes mellitus (ie, fermentation of diabetic urine) or in those undergoing urinary tract instrumentation. Pneumaturia is more likely to occur in patients with diverticulitis or Crohn disease than in those with cancer. Fecaluria is pathognomonic of a fistula and occurs in approximately 40% of cases. Patients may describe passing vegetable matter in the urine. The flow through the fistula predominantly occurs from the bowel to the bladder. Patients very rarely pass urine from the rectum 20.

Symptoms of the underlying disease causing the fistula may be present. Abdominal pain is more common in patients with Crohn disease, but an abdominal mass is discovered in fewer than 30% of patients. In patients with Crohn disease who have a fistula, abdominal mass and abscess are more common 20.

Vesicointestinal fistula diagnosis

Various modalities of diagnosis are available:

- Cystoscopy

- Sigmoidoscopy – ideally, flexible rather than rigid

- Colonoscopy

- Barium enema

- Poppy seed test

- Cystography

- Intravenous urography

- Dye markers such as methylene blue

- Abdominopelvic CT

- MRI

In most cases, vesicointestinal fistula occurs through the dome of the bladder (~ 60%). The posterior wall (~ 30%) and trigone (~ 10%) are less frequent sites 5. Vesicointestinal fistulas and its cause can be characterized in a number of ways, although the fistulous tract itself is often difficult to demonstrate.

Computed tomography

CT (computed tomography) scanning of the abdomen and pelvis is the most sensitive imaging test for detecting a vesicointestinal fistula, and CT scanning should be included as part of the initial evaluation of suspected colovesical fistulae 32. CT scanning can demonstrate small amounts of air or contrast material in the bladder, localized thickening of the bladder wall, or an extraluminal gas-containing mass adjacent to the bladder. Three-dimensional reconstruction is useful when traditional axial and coronal images fail to demonstrate the anatomy in sufficient detail 33.

Avoiding oral contrast ingestion and having the patient evacuate rectally administered barium can enhance the value of CT scanning in the process of fistula identification 34. CT scanning also plays an important role in preoperative surgical planning by demonstrating the extent and degree of pericolonic inflammation.

3-dimensional CT scanning provided improved imaging of the anatomic relationships. Additionally, multidetector row CT urography is useful in identifying urinary tract abnormalities, including fistulae 35. More sophisticated CT imaging modalities, such as CT colonoscopy, have been reported in the literature, but no clinical trials demonstrating a clinical benefit to this modality over traditional CT scanning have been published to date 36.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can be used to identify enterovesical fistulae. In a study of 25 patients with Crohn disease, 16 patients had enterovesical, deep perineal, or cutaneous fistulae. One false-negative result occurred in a patient who had a vesicointestinal fistula 37. Some authors recommend MRI evaluation in patients with Crohn disease given the presence of chronic inflammation and superior anatomic detail in relation to the anal sphincter. Another benefit is that this study does not expose the patient to additional radiation 38.

T1-weighted images delineate the extension of the fistula relative to sphincters and adjacent hollow viscera and show inflammatory changes in fat planes.

T2-weighted images show fluid collections within the fistula, localized fluid collections in extra-intestinal tissues, and inflammatory changes within muscles.

MRI may be useful in identifying deep perineal fistulae but is not generally used in the routine workup of vesicointestinal fistulae. In a study of 22 patients who presented with symptoms suggestive of vesicointestinal fistula, MRI was performed in conjunction with cystoscopy. Afterward, 19 of the patients underwent laparotomy and repair. They found that MRI correctly identified 18 cases of fistula. Fistula was ruled out in the remaining patient. This data showed MRI to be a highly sensitive and specific study for vesicointestinal fistula.

Although MRI is an excellent study, the increasing image quality of CT scanning, together with the high cost and limited availability of MRI, limit the practical application MRI as a diagnostic study for enterovesical fistulae 39.

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy can be a helpful component of the diagnostic evaluation. Prior to the advancement of radiological diagnostic techniques, cystoscopy was considered to be the most reliable method of diagnosis 30. The findings of this procedure can suggest the presence of a fistula, and cystoscopy can be used to evaluate for a possible malignancy.

Cystoscopy can be useful in paring down the list of differential diagnoses, and it enables the physician to obtain a biopsy of the fistula to check for malignancy. Localized erythema, papillary/bullous mucosal changes, and, occasionally, material oozing through an area are present in 80%-90% of diagnosed cases.

Poppy seed test

The poppy seed test has recently proven to be a potentially helpful diagnostic tool. This test consists of administering 1.25 g of poppy seeds with 12 ounces of fluid or 6 ounces of yogurt to the patient. The urine is then collected for the next 48 hours and examined for poppy seeds.

In a recent trial, the accuracy of the poppy seed test was compared with CT scanning and nuclear cystography in 20 patients with surgically confirmed fistulae. The poppy seed test yielded a 100% detection rate, whereas CT scanning and nuclear cystography yielded rates of 70% and 80%, respectively. Because of the low cost of the test ($5.37 for the poppy seed test, $652.92 for CT scanning, $490.83 for nuclear cystography), this may serve as an excellent confirmatory test when fistula is suspected. An obvious problem with the poppy seed test is that it provides little detail as to the location and type of fistula present 40.

Laboratory studies

Urinalysis usually shows a full field of white blood cells, bacteria, and debris. A variant of the Bourne test (see Bourne test) using orally administered charcoal is also helpful. Charcoal in the urine is detected either visually or microscopically in the centrifuged urine 41.

Urine culture findings are typically interpreted as mixed flora, although the most common organism identified is Escherichia coli. In the setting of sepsis, attempts should be made to characterize the predominant organisms and to obtain sensitivities to guide further therapy. Recurrent UTIs with various organisms are consistent with, but not diagnostic of, enterovesical fistulae.

Blood studies should include measurement of the blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and electrolytes; findings are typically within the reference range. The results of the complete blood cell count (CBC) are typically normal. Leukocytosis may be found in cases associated with focal areas of undrained abscess or development of florid cystitis or pyelonephritis. Anemia may be present in patients with chronic disease and may be associated with malignancy.

When large areas of inflammation are appreciated or when abscess is involved, possible ureteral involvement should be considered, especially in the setting of any hydronephrosis. Preoperative evaluation with retrograde pyelography or intravenous pyelography (IVP) helps to demonstrate the extent of involvement for surgical repair 42.

Vesicointestinal fistula treatment

Vesicointestinal fistula treatment involves treating the underlying cause. Any abscess should be drained.

Antibiotic therapy is recommended in the interim, particularly in patients with vesicointestinal fistula, to prevent urinary and renal sepsis.

Nonsurgical treatment of vesicointestinal fistulae may be a viable option in patients who cannot tolerate general anesthesia or in selected patients who can be maintained on prolonged antibacterial therapy for symptomatic relief.

Vesicointestinal fistulae in patients with diverticulitis who are deemed to be a surgical risk have been managed conservatively. In highly select patients, nonoperative therapy has been reported as a viable treatment option. Six patients observed for 3-14 years encountered little inconvenience and were without significant complications while on intermittent antibacterial therapy alone 43. In another study, six patients who declined surgical intervention were monitored and were found to exhibit no significant changes in renal function, and urosepticemia was not documented 44.

If the fistula closes spontaneously, which occurs in as many as 50% of patients with diverticulitis, requirements for resection depend on the nature of the underlying colonic disease. Some patients tolerate a vesicointestinal fistula so well that surgery is deferred indefinitely. However, although some small studies have suggested conservative management as a reasonable option, no randomized controlled trials have supported conservative management, and careful selection with close follow-up is stressed.

For enterovesical fistulae due to Crohn disease, medical therapy is the first choice 45. Zhang et al 46 reported that 13 of 37 patients with Crohn disease achieved long-term remission of enterovesical fistulae over a mean of 4.7 years through treatment with antibiotics, azathioprine, steroids, and/or infliximab. Significant risk factors for surgery included sigmoid-originated fistulae and concurrent Crohn disease complications such as small bowel obstruction, abscess formation, enterocutaneous fistula, enteroenteric fistula, and persistent ureteral obstruction or urinary tract infection.

In a study analyzing the outcomes of 97 patients with enterovesical fistulae due to Crohn disease, the use of anti-TNF agents was associated with an increased rate of remission without need for surgery 47. A review of Crohn disease–related internal fistulae, including 16 enterovesical fistulae, treated with anti-TNF agents (infliximab or adalimumab) reported a cumulative surgery rate of 47.2%, and a fistula closure rate of 27.0% at 5 years from the induction of anti-TNF therapy 48.

Patients with advanced carcinoma may be treated with catheter drainage of the bladder alone or supravesical percutaneous diversion.

Vesicointestinal fistula surgery

The documented presence of a fistula that is causing symptoms or adversely affecting quality of life is an indication for surgical intervention in patients with enterovesical fistulae. Fistulae should be repaired in patients with any of the following:

- Abdominal pain

- Dysuria

- Malodorous urine

- Incontinence

- Urinary outlet obstruction

- Recurrent cystitis

- Bouts of sepsis

- Pyelonephritis

Patients at high surgical risk may be treated with medical therapy and catheter drainage but may ultimately require at least diverting surgery if symptoms persist. Patients with terminal cancer are often better treated conservatively or with simple diversions.

Open surgery

Vesicointestinal fistulae can almost always be treated with resection of the involved segment of colon and primary reanastomosis. Fistulae due to inflammation are generally managed with resection of the primarily affected diseased segment of intestine, with repair of the bladder only when large visible defects are present. The bladder usually heals uneventfully with temporary urethral catheter drainage. Suprapubic tube diversion is an option but is not necessary 49.

Historically, staged procedures were used to treat vesicointestinal fistula. Staged repairs may be more judicious in patients with large intervening pelvic abscesses or in those with advanced malignancy or radiation changes. Most cases do not involve abscesses. If an abscess is present, spontaneous drainage through the fistula into the bladder may alleviate the immediate need for drainage if the bladder is emptying under low pressure. Further operations may be delayed pending culture results and after adequate antibiotic therapy has reduced the inflammation. A one-stage operation is recommended for patients in good general health who have a well-organized fistula and no systemic infection 50.

A diverting colostomy, with or without urinary diversion, may be used as a long-term solution for palliation or severe radiation damage in cases of advanced cancer.

Endoscopic treatment

A review of the literature reveals one reported case of a vesicointestinal fistula treated with transurethral resection with no evidence of recurrence in more than 2 years of follow-up 51. With the development and advancements of hemostatic sealants, endoscopic injection of these materials is possible as a minimally invasive treatment. One concern would be the presence of foreign material in direct contact with the urine possibly acting as a nidus for stone formation. Few clinical trails have studied the application of these sealants, and this author does not recommend their use from an endoscopic approach.

Laparoscopic treatment

Several reports suggest that laparoscopic resection and reanastomosis of the offending bowel segment is possible as a minimally invasive treatment 52. However, an abdominal incision is still required for removal of the affected intestinal segment intact for pathological assessment to rule out cancer.

Follow-up

After repair of fistulae caused by benign disease, the urinary catheter is left in place for 5-7 days or longer depending on the level of inflammation and size of the repair. The patient remains on appropriate antibiotics (ie, based on preoperative culture findings and sensitivity). At the next observation, a repeat urine culture with sensitivity is obtained. The author’s preference is to perform a gravity cystography with postdrainage films to confirm healing before catheter removal. Antibiotics are continued for 24-48 hours after catheter removal until the culture results are documented as negative.

Thereafter, the primary enteric process is treated as indicated, and the patient is periodically observed with urinalysis and cultures as indicated. Patients are usually aware of the symptoms of recurrence and should be encouraged to return early if they experience any indication of infection, pneumaturia, or fecaluria.

If cancer resection is performed, observational colonoscopy and CT scanning are obtained as indicated based on tumor histology findings and stage. Periodic cystoscopy may also be indicated because of the possibility of local recurrence in the detrusor muscle. Cystoscopy is especially important if the margin status of the tumor is questionable.

Certainly, any hematuria in the postoperative period should be carefully evaluated with upper tract imaging and cystoscopy.

Vesicointestinal fistula surgery complications

In a 1988 study, Woods et al 53 reported a 3.5% operative mortality rate and a complication rate of 27%. Fistula recurrences have been reported in 4%-5% of patients. Most other studies have not reported such high operative mortality rates, except in the cases of severely ill patients with other significant medical problems.

Short-term complications include the usual potential problems after general surgery (eg, fever, atelectasis, slow return of bowel function, catheter-related UTI, deep vein thrombosis [DVT], wound breakdown and infection). These complications are largely preventable with incentive spirometry, early ambulation, thromboembolic hose or anticoagulation in susceptible patients, and appropriate wound-closure techniques.

Long-term complications include persistent bladder leak (usually observed after radiotherapy for carcinoma), recurrence of a fistula (also more likely after radiotherapy), pelvic/abdominal abscess (from a leaking anastomosis), cutaneous fistulization (also from a leaking anastomosis), and bowel obstruction (from adhesions or recurrent diverticulitis).

Consider recurrent cancer in the abdomen or previously involved bladder wall when patients return with signs of bowel obstruction, new hematuria, or irritative voiding. Repeat CT scanning, serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) measurement, urine culture and cytology, and cystoscopy are indicated in these settings.

Vesicointestinal fistula surgery contraindications

Poor overall general health, inability to tolerate general or regional anesthesia, and terminal cancer are contraindications to aggressive management of enterovesical fistula. Patients with those contraindications may be served better with medical therapy or less-invasive diversions (eg, colostomy, ureterostomy, percutaneous drainage).

Vesicointestinal fistula prognosis

In a retrospective record review of 76 patients diagnosed with vesicointestinal fistula over a 12-year period, the complication rate in those treated with single-stage repair was not statistically different from that in patients who underwent multistage repair 54.

In general, the overall outcome and prognosis are excellent in patients with non–radiation-induced or cancer-induced fistulae. Such patients usually respond well to resection of the diseased colon and have no significant urinary sequelae.

The prognosis in patients with colon carcinoma and fistulization is less favorable because the involvement of the bladder usually heralds a more aggressive tumor that often is metastatic at the time of detection.

Radiation-induced fistulae are more likely to recur, but the long-term patient prognosis may be better if the malignancy for which the radiation was administered has been controlled.

References- Enterovesical Fistula. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/442000-overview

- Pollard SG, Macfarlane R, Greatorex R, Everett WG, Hartfall WG. Colovesical fistula. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1987;69(4):163–165. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2498444/pdf/annrcse01545-0017.pdf

- Kaiser AM. McGraw-Hill Manual Colorectal Surgery. McGraw-Hill Professional. (2008) ISBN:0071590706.

- Malignant stricture with colovesical fistula: stent insertion in the colon. W Cwikiel and A Andrén-Sandberg. Radiology 1993 186:2, 563-564.

- Pollard SG, Macfarlane R, Greatorex R, Everett WG, Hartfall WG. Colovesical fistula. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1987;69(4):163-165.

- Skierucha M, Barud W, Baraniak J, Krupski W. Colovesical fistula as the initial manifestation of advanced colon cancer: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2018;6(12):538–541. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v6.i12.538 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6212606

- Golabek T, Szymanska A, Szopinski T, Bukowczan J, Furmanek M, Powroznik J, Chlosta P. Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:617967.

- McCaffrey JC, Foo FJ, Dalal N, Siddiqui KH. Benign multicystic peritoneal mesothelioma associated with hydronephrosis and colovesical fistula formation: report of a case. Tumori. 2009;95:808–810.

- Yahagi N, Kobayashi Y, Ohara T, Suzuki N, Kiguchi K, Ishizuka B. Ovarian carcinoma complicated by sigmoid colon fistula formation: a case report and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:250–253.

- Balsara KP, Dubash C. Complicated sigmoid diverticulosis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1998 Apr. 17(2):46-7.

- Corman ML. Colovesical fistula complicating diverticulitis in brothers. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999 Nov. 42(11):1511.

- Charúa-Guindic L, Jiménez-Bobadilla B, Reveles-González A, Avendaño-Espinosa O, Charúa-Levy E. [Incidence, diagnosis and treatment of colovesical fistula]. Cir Cir. 2007 Sep-Oct. 75(5):343-9.

- Dearden C, Humphreys WG. Meckel’s diverticulum: a vesico-diverticular fistula. Ulster Med J. 1983. 52(1):73-4.

- Kuntze JR, Herman MH, Evans SG. Genitourinary coccidioidomycosis. J Urol. 1988 Aug. 140(2):370-4.

- Piper JV, Stoner BA, Mitra SK, Talerman A. Ileo-vesical fistula associated with pelvic actinomycosis. Br J Clin Pract. 1969 Aug. 23(8):341-3.

- Cakmak MA, Aaronson IA. Appendicovesical fistula in a girl with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1997 Dec. 32(12):1793-4.

- Carter D, Choi HY, Telford G, Otterson M, Chitapalli K, Pintar K. Lymphadenopathy and entero-vesical fistula in Fabry’s disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988 Dec. 90(6):726-31.

- Téllez Martinez-Fornés M, Fernandez A, Burgos F, et al. Colovesical fistula secondary to vesical gangrene in a diabetic patient. J Urol. 1991 Oct. 146(4):1115-7.

- Abbas F, Memon A. Colovesical fistula: an unusual complication of prostatomegaly. J Urol. 1994 Aug. 152(2 Pt 1):479-81.

- Pontari MA, McMillen MA, Garvey RH, Ballantyne GH. Diagnosis and treatment of enterovesical fistulae. Am Surg. 1992 Apr. 58(4):258-63.

- Dawam D, Patel S, Kouriefs C, Masood S, Khan O, Sheriff MK. A “urological” enterovesical fistula. J Urol. 2004 Sep. 172(3):943-4.

- Paul AB, Thomas JS. Enterovesical fistula caused by small bowel lymphoma. Br J Urol. 1993 Jan. 71(1):101-2.

- Miller B, Morris M, Gershenson DM, et al. Intestinal fistulae formation following pelvic exenteration: a review of the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience, 1957-1990. Gynecol Oncol. 1995 Feb. 56(2):207-10.

- Levenback C, Gershenson DM, McGehee R, et al. Enterovesical fistula following radiotherapy for gynecologic cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1994 Mar. 52(3):296-300.

- Ansari MS, Nabi G, Singh I, et al. Colovesical fistula an unusual complication of cytotoxic therapy in a case of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Int Urol Nephrol. 2001. 33(2):373-4.

- Bordbar M, Kamali K, Basiratnia M, Fourotan H. Enterovesical fistula as a result of neutropenic enterocolitis in a pediatric patient with acute leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017 Apr. 64 ,4

- Crispen PL, Kansas BT, Pieri PG, Fisher C, Gaughan JP, Pathak AS, et al. Immediate postoperative complications of combined penetrating rectal and bladder injuries. J Trauma. 2007 Feb. 62(2):325-9.

- Daoud F, Awwad ZM, Masad J. Colovesical fistula due to a lost gallstone following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2001. 31(3):255-7.

- Kaiser AM. McGraw-Hill Manual Colorectal Surgery. McGraw-Hill Professional. (2008) ISBN:0071590706

- Driver CP, Anderson DN, Findlay K, et al. Vesico-colic fistulae in the Grampian region: presentation, assessment, management and outcome. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1997 Jun. 42(3):182-5.

- Krco MJ, Jacobs SC, Malangoni MA, Lawson RK. Colovesical fistulas. Urology. 1984 Apr. 23(4):340-2.

- Golabek T, Szymanska A, Szopinski T, Bukowczan J, Furmanek M, Powroznik J, et al. Enterovesical fistulae: aetiology, imaging, and management. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013. 2013:617967.

- Shinojima T, Nakajima F, Koizumi J. Efficacy of 3-D computed tomographic reconstruction in evaluating anatomical relationships of colovesical fistula. Int J Urol. 2002 Apr. 9(4):230-2.

- Narumi Y, Sato T, Kuriyama K, Fujita M, Mitani T, Kameyama M. Computed tomographic diagnosis of enterovesical fistulae: barium evacuation method. Gastrointest Radiol. 1988 Jul. 13(3):233-6.

- Caoili EM, Cohan RH, Korobkin M, et al. Urinary tract abnormalities: initial experience with multi-detector row CT urography. Radiology. 2002 Feb. 222(2):353-60.

- Ing A, Lienert A, Frizelle F. Medical image. CT colonography for colovesical fistula. N Z Med J. 2008 Aug 8. 121(1279):105-8.

- Haggett PJ, Moore NR, Shearman JD, Travis SP, Jewell DP, Mortensen NJ. Pelvic and perineal complications of Crohn’s disease: assessment using magnetic resonance imaging. Gut. 1995 Mar. 36(3):407-10.

- Koelbel G, Schmiedl U, Majer MC, et al. Diagnosis of fistulae and sinus tracts in patients with Crohn disease: value of MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989 May. 152(5):999-1003.

- Ravichandran S, Ahmed HU, Matanhelia SS, Dobson M. Is there a role for magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosing colovesical fistulas?. Urology. 2008 Oct. 72(4):832-7.

- Kwon EO, Armenakas NA, Scharf SC, Panagopoulos G, Fracchia JA. The poppy seed test for colovesical fistula: big bang, little bucks!. J Urol. 2008 Apr. 179(4):1425-7.

- Corman ML. Colovesical Fistula. Colon and Rectal Surgery. Philadelphia, Pa: JB Lippincott; 1984. 505.

- Rames RA, Bissada N, Adams DB. Extent of bladder and ureteric involvement and urologic management in patients with enterovesical fistulas. Urology. 1991 Dec. 38(6):523-5.

- Amin M, Nallinger R, Polk HC Jr. Conservative treatment of selected patients with colovesical fistula due to diverticulitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984 Nov. 159(5):442-4.

- Solkar MH, Forshaw MJ, Sankararajah D, Stewart M, Parker MC. Colovesical fistula–is a surgical approach always justified?. Colorectal Dis. 2005 Sep. 7(5):467-71.

- Fiocchi C. Closing fistulas in Crohn’s disease–should the accent be on maintenance or safety?. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 26. 350(9):934-6.

- Zhang W, Zhu W, Li Y, Zuo L, Wang H, Li N, et al. The respective role of medical and surgical therapy for enterovesical fistula in Crohn’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014 Sep. 48(8):708-11.

- Taxonera C, Barreiro-de-Acosta M, Bastida G, et al. Outcomes of Medical and Surgical Therapy for Entero-urinary Fistulas in Crohn’s Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016 Jun. 10 (6):657-62.

- Kobayashi T, Hishida A, Tanaka H, Nuki Y, Bamba S, Yamada A, et al. Real-world Experience of Anti-tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy for Internal Fistulas in Crohn’s Disease: A Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Dec. 23 (12):2245-2251.

- Ferguson GG, Lee EW, Hunt SR, Ridley CH, Brandes SB. Management of the bladder during surgical treatment of enterovesical fistulas from benign bowel disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2008 Oct. 207(4):569-72.

- Kirsh GM, Hampel N, Shuck JM, Resnick MI. Diagnosis and management of vesicoenteric fistulas. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991 Aug. 173(2):91-7.

- Van Thillo EL, Delaere KP. Endoscopic treatment of colovesical fistula. An endoscopical approach. Acta Urol Belg. 1992. 60(2):151-2.

- Perniceni T, Burdy G, Gayet B, et al. [Results of elective segmental colectomy done with laparoscopy for complicated diverticulosis]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2000 Feb. 24(2):189-92.

- Woods RJ, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, et al. Internal fistulas in diverticular disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988 Aug. 31(8):591-6.

- McBeath RB, Schiff M, Allen V, et al. A 12-year experience with enterovesical fistulas. Urology. 1994 Nov. 44(5):661-5.