Vitreomacular adhesion

Vitreomacular adhesion (VMA) is clinically defined as the vitreous being attached within a 3-mm radius of the fovea, with surrounding separation of the cortical vitreous above the neurosensory retina 1. Vitreomacular adhesion occurs when there is incomplete or anomalous posterior vitreous detachment from the retinal internal limiting membrane 2. In addition, the retina should have no changes in surface contour or morphologic features on optical coherence tomography (OCT). Vitreomacular adhesion can be subclassified as focal (≤1500 μm) or broad (>1500 μm) based on the size of the adhesion 3.

As a part of natural aging, the process of posterior vitreous detachment occurs naturally; the vitreous liquefies and releases itself from the vitreoretinal interface 2. Typically, this is a normal process; however, in some cases, the posterior vitreous detachment can become pathological when vitreous liquefaction occurs without concomitant vitreoretinal interface weakening 4. Under these circumstances, the volume displacement from the central vitreous to the preretinal space is only able to achieve partial vitreous separation from the retina. This condition is referred to as anomalous posterior vitreous detachment (also referred to as incomplete or partial posterior vitreous detachment) 5. It may result from disorders that cause premature vitreous liquefaction, such as high myopia, vitreous hemorrhage, uveitis, hereditary vitreoretinal syndromes, trauma, retinal vascular diseases and aphakia 6. When the area of remaining attachment is in the macula (the area of the retina responsible for central vision), this attachment is known as vitreomacular adhesion 7.

Vitreomacular adhesion has emerged as a distinct clinical entity, evidenced by the recent assignment of an International Classification of Diseases (ICD) – Clinical Manifestations code. This persistent adhesion can lead to symptoms (i.e., symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion), including metamorphopsia (distorted vision), decreased visual acuity and central visual field defect. These symptoms are as a direct result of traction caused by the persistent vitreomacular adhesion at the vitreomacular interface, often referred to as vitreomacular traction. Vitreomacular adhesion and vitreomacular traction are two of the many entities along the spectrum during the course of an incomplete posterior vitreous detachment, also referred to as anomalous posterior vitreous detachment 8. Vitreomacular traction occurs as the result of vitreomacular adhesions in a detaching posterior vitreous. Vitreomacular traction can sometimes lead to the formation of a full-thickness macular hole. Hence, the term symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion encompasses symptomatology due to Vitreomacular traction and its consequences, such as macular hole.

The prevalence of vitreomacular adhesion was estimated at 14.74% in a random sample of patients from the three retina clinics in the USA 9.

Vitreomacular adhesion can be asymptomatic without complications 9. In some cases, however, vitreomacular adhesion can be symptomatic, contributing to the pathogenesis and clinical course of various ocular conditions 10, including vitreomacular traction syndrome 11, idiopathic macular hole 12, cystoid macular edema 13, diabetic macular edema 14, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) 15. Symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion can be associated with loss of visual function 16. It has been estimated that 1.5% of the population has eye disease caused by or associated with, vitreomacular adhesion 16. There are limited epidemiological data on vitreomacular traction syndrome, macular hole, diabetic macular edema, and other conditions linked to vitreomacular adhesion, and in certain conditions, the relationship to vitreomacular adhesion is not clear 17. In a meta-analysis, eyes with neovascular AMD (age-related macular degeneration) were two times more likely to have vitreomacular adhesion compared with controls. In addition, vitreomacular traction was present in 28.7% of eyes with diabetic macular edema 17. Such estimates are typically based on small sample sizes 17. The prevalence of symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion is not well documented. With imaging techniques such as optical coherence tomography (OCT), it may be possible to estimate vitreomacular adhesion prevalence. OCT, a noninvasive technique used to diagnose macular conditions, has been increasingly used to identify vitreomacular adhesion, because it is more sensitive than using clinical examination alone 18.

Vitreomacular adhesion OCT-based definition 19:

The following must be present on at least one OCT B-scan image:

- Partial vitreous detachment as indicated by elevation of cortical vitreous above the retinal surface in the perifoveal area

- Persistent vitreous attachment to the macula within a 3-mm radius from the center of the fovea

- Acute angle between posterior hyaloid and inner retinal surface

- Absence of changes in foveal contour or retinal morphology.

Vitreomacular adhesion OCT-based classification 19:

- Focal: Width of attachment ≤1500 μm

- Broad: Width of attachment >1500 μm

- Concurrent: Associated with other macular abnormalities (e.g. age-related macular degeneration, retinal vein occlusion, diabetic macular edema)

- Isolated: Not associated with other macular abnormalities

Vitreomacular traction OCT-based definition 19:

The following must be present on at least one OCT B-scan image:

- Partial vitreous detachment as indicated by elevation of cortical vitreous above the retinal surface in the perifoveal area

- Persistent vitreous attachment to the macula within a 3-mm radius from the center of the fovea

- Acute angle between posterior hyaloid and inner retinal surface

- Presence of changes in foveal contour or retinal morphology (distortion of foveal surface, intraretinal structural changes such as pseudocyst formation, elevation of fovea from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), or a combination of any of these three features)

- Absence of full thickness interruption of all retinal layers

Vitreomacular traction OCT-based classification 19:

- Focal: Width of attachment ≤1500 μm

- Broad: Width of attachment >1500 μm

- Concurrent: Associated with other macular abnormalities (e.g. age-related macular degeneration, retinal vein occlusion, diabetic macular edema)

- Isolated: Not associated with other macular abnormalities.

Vitreomacular adhesion causes

With age, the vitreous gel undergoes liquefaction forming pockets of fluid within the vitreous (synchysis) which leads to a contraction or condensation (syneresis) of the vitreous. With loss of vitreous volume, there is a tractional pull exerted at sites of vitreoretinal and vitreopapillary attachments by means of the condensing dense vitreous cortex.

At the same time, there is weakening of these attachments between the vitreous and the internal limiting membrane (ILM) and it is proposed that detachment of the posterior hyaloid proceeds in the following sequence 20.:

- (i) Perifoveal region (possibly, temporal followed by nasal)

- (ii) Superior and inferior vascular arcades

- (iii) Fovea

- (v) Mid-peripheral retina

- (vi) Optic disc (when vitreous is detached fully from the optic disc, commonly associated with the Weiss ring, it is called a complete posterior vitreous detachment)

When anterior vitreous pull and weakening of attachments occur synchronously, a normal posterior vitreous detachment occurs. However, when these occur asynchronously (tractional component preceding or proceeding faster than the vitreoretinal detachment), an anomalous posterior vitreous detachment develops which can result in vitreomacular adhesion, vitreomacular traction and other vitreoretinal diseases. The vitreomacular traction progression can correlate with various stages of full thickness macular hole 21.

The vitreous is most firmly attached to the retina in areas where the internal limiting membrane (ILM) is the thinnest including:

- anteriorly at the vitreous base,

- surrounding lattice degeneration,

- enclosed ora bays, and retinal tufts; and

- posteriorly along major retinal vessels,

- optic disc margins, and

- certain areas of the macula – mainly to the foveola (500 μm diameter area in the center of macula) and the margin of the fovea (circumference of the 1500 μm diameter fovea) 22.

This partly explains the persistence of foveal attachment in vitreomacular traction. When the posterior hyaloid detaches from the posterior pole and macula, but remains attached at the fovea, the detached portion of posterior hyaloid lies anterior to the plane of vitreofoveal attachment. This leads to a static anterior traction due to the elastic properties of the vitreous and results in foveal elevation or distortion. Additionally, ocular rotations occurring with eye movements may exert dynamic anterior traction at the site of the vitreofoveal attachment. Such dynamic traction seems to be of greater importance than the static traction in vitreomacular traction 23. A smaller diameter of vitreofoveal adhesion is associated with higher tractional stress (force per unit area) resulting in greater foveal deformation 24. A vitreofoveal adhesion ≤500 μm is associated with vitreofoveolar traction syndrome (in addition to microhole, lamellar hole, and full-thickness macular hole), while a vitreofoveal adhesion approximating 1500 μm is associated with vitreomacular traction syndrome (in addition to exacerbation of concurrent diseases including tractional diabetic macular edema and exudative age-related macular degeneration) 23. Although still debated, both anteroposterior (vitreo-macular) and tangential (epiretinal/vitreoschisis remnants) tractional forces are thought to contribute to vitreomacular traction.

The anomalous adherence of the posterior hyaloid to the retina can be either a primary abnormality or develop secondary to cellular proliferation from cortical vitreous remnants after a partial posterior vitreous detachment, also known as vitreoschisis, or from concurrent diseases (e.g. proliferative diabetic retinopathy) that provide a fibrovascular scaffold for cellular proliferation and contraction. An epiretinal membrane (ERM) is commonly associated with both the vitreofoveal and vitreomacular traction. It has been shown to proliferate from the retinal surface, coursing up the cone of attached vitreous, and then growing along the back surface of the detached perifoveal hyaloid 23.

Epiretinal membrane (ERM) is thought to exacerbate vitreomacular traction by:

- (i) strengthening vitreomacular adhesion and preventing spontaneous detachment in the short-term, and

- (ii) adding to the anterior traction via fibrocellular proliferation and contraction in the long-term 23.

Vitreopapillary adhesion (VPA) and vitreopapillary traction (VPT) may potentiate or facilitate the vitreomacular tractional forces as well 25.

Histopathology of vitreomacular traction specimens shows fibrocellular proliferation consisting of fibrous astrocytes, myofibroblasts, fibrocytes and RPE cells 26. It usually forms a ‘double membrane’ that bridges the posterior hyaloidal and the retinal interfaces. Transmission electron microscopy of vitreomacular traction specimens has confirmed the presence of myofibroblasts, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells, fibrocytes and macrophages, and recognized two distinct types of vitreomacular traction:

- (i) a multilayer of fibrocellular tissue (ERM) proliferating into native vitreous collagen and

- (ii) a monolayer of cells proliferating along the ILM directly 27.

The distinction of these two types of ERM are thought to be determined by the presence or absence of vitreoschisis which leaves behind cortical vitreous remnants on the epiretinal surface 28. Bone marrow derived progenitor cells may contribute to vitreomacular traction as well 27.

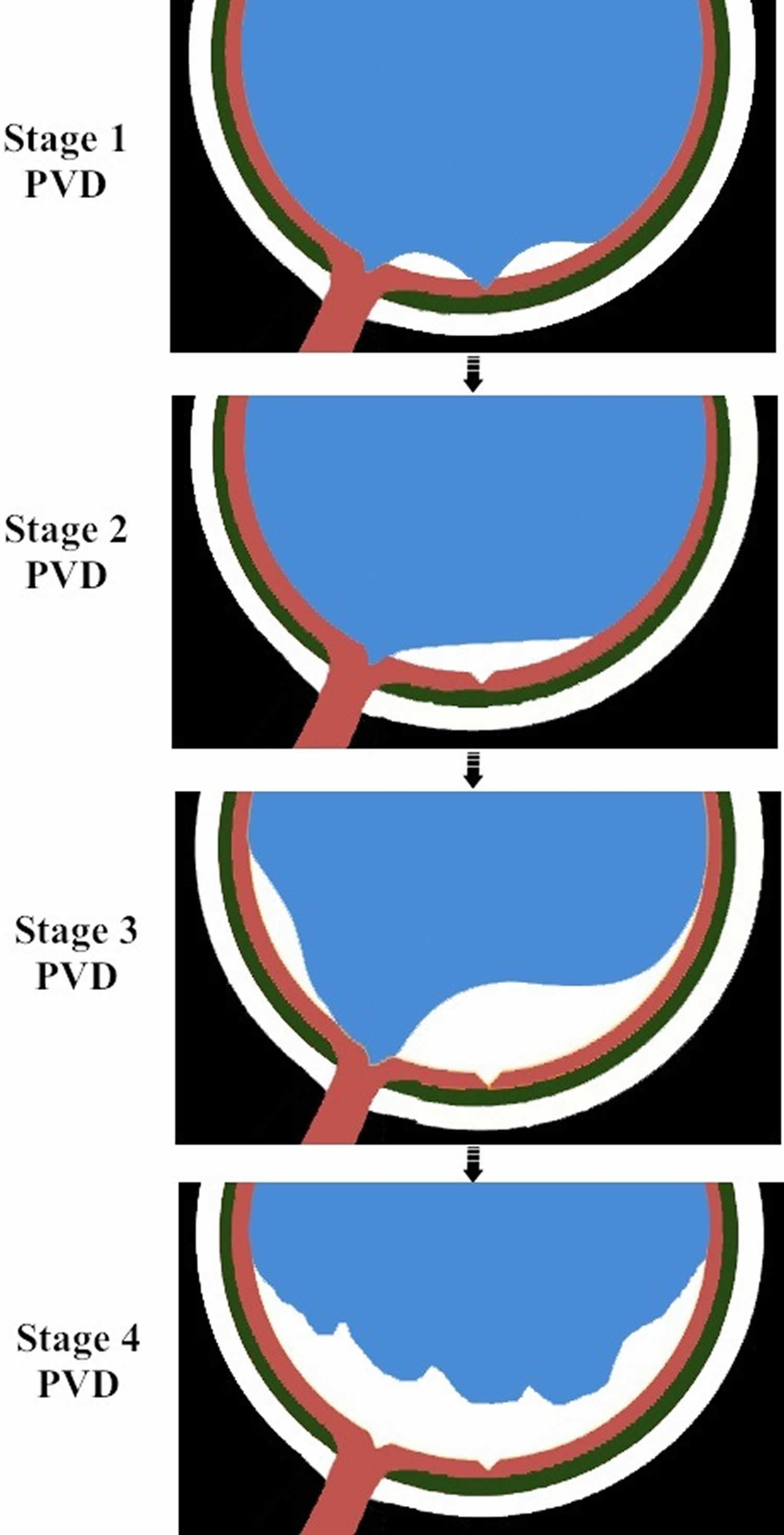

Figure 1. Evolution of normal posterior vitreous detachment (PVD)

Footnotes: Stage 1 consists of perifoveal vitreous detachment with persistence of vitreous attachment to the fovea, mid-peripheral retina and the optic disc. Stage 2 consists of vitreofoveal detachment with persistence of vitreous attachment to the mid-peripheral retina and the optic disc. Stage 3 consists of vitreous detachment from mid-peripheral retina with persistent attachment to the optic disc. Stage 4 or complete posterior vitreous detachment consists of detachment of the vitreous from the optic disc. Stage 1 of posterior vitreous detachment can present as vitreomacular adhesion (VMA) or vitreomacular traction (VMT). Stages 2 and 3 of posterior vitreous detachment can present as vitreopapillary adhsion (VPA) or vitreopapillary traction (VPT). The evolution of posterior vitreous detachment may deviate from this typical pattern.

Figure 2. Perifoveal posterior vitreous detachment

Footnote: (A) Pictorial representation of the eye shows two pockets of vitreous gel liquefaction and a perifoveal posterior vitreous detachment associated with persistent attachment of the vitreous to the foveal region (B). Optical coherence tomography of the vitreomacular interface shows vitreomacular traction (C) resulting from the incomplete posterior vitreous detachment.

Vitreomacular adhesion symptoms

Vitreomacular adhesion is asymptomatic.

Vitreomacular traction: Symptomatic with blurred or reduced vision, metamorphopsia, micropsia, scotoma, and difficulties with daily vision-related tasks such as reading 20. Onset and progression of symptoms are usually gradual, except in a few cases of sudden onset of vision loss/scotoma due to severe traction causing foveal detachment 26.

Vitreomacular adhesion diagnosis

Vitreomacular adhesion diagnosis is usually confirmed by optical coherence tomography (OCT). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) allows noninvasive visualization and imaging of vitreomacular interface and is an important tool in the diagnosis and management of vitreomacular adhesion and vitreomacular traction syndrome, especially with the advent of non-surgical management with pharmacologic vitreolysis.

Vitreomacular adhesion OCT-based definition 19:

The following must be present on at least one OCT B-scan image:

- Partial vitreous detachment as indicated by elevation of cortical vitreous above the retinal surface in the perifoveal area

- Persistent vitreous attachment to the macula within a 3-mm radius from the center of the fovea

- Acute angle between posterior hyaloid and inner retinal surface

- Absence of changes in foveal contour or retinal morphology.

Vitreomacular adhesion OCT-based classification 19:

- Focal: Width of attachment ≤1500 μm

- Broad: Width of attachment >1500 μm

- Concurrent: Associated with other macular abnormalities (e.g. age-related macular degeneration, retinal vein occlusion, diabetic macular edema)

- Isolated: Not associated with other macular abnormalities

Vitreomacular traction OCT-based definition 19:

The following must be present on at least one OCT B-scan image:

- Partial vitreous detachment as indicated by elevation of cortical vitreous above the retinal surface in the perifoveal area

- Persistent vitreous attachment to the macula within a 3-mm radius from the center of the fovea

- Acute angle between posterior hyaloid and inner retinal surface

- Presence of changes in foveal contour or retinal morphology (distortion of foveal surface, intraretinal structural changes such as pseudocyst formation, elevation of fovea from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), or a combination of any of these three features)

- Absence of full thickness interruption of all retinal layers

Vitreomacular traction OCT-based classification 19:

- Focal: Width of attachment ≤1500 μm

- Broad: Width of attachment >1500 μm

- Concurrent: Associated with other macular abnormalities (e.g. age-related macular degeneration, retinal vein occlusion, diabetic macular edema)

- Isolated: Not associated with other macular abnormalities.

Vitreomacular adhesion treatment

The goal of therapy for symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion and related conditions is to relieve tractional effects on the macula, thereby resolving the underlying condition with subsequent functional improvement.

Intravitreal ocriplasmin (formerly, microplasmin) pharmacotherapy is the treatment of choice to relieve symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion 29. Asymptomatic vitreomacular adhesion is not an indication for ocriplasmin use 30. Ocriplasmin is a proteolytic enzyme indicated for the treatment of symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion 31. The vitreoretinal interface consists of the vitreous cortex attached to the internal limiting membrane of the retina by means of several extracellular matrix proteins such as laminin, fibronectin, and certain collagens (types VI, VII, XVIII) 32. Ocriplasmin is a recombinant truncated form of human plasmin that has proteolytic activity against these proteins anchoring the vitreoretinal interface. More importantly, ocriplasmin lacks activity against type IV collagen, an important component of internal limiting membrane, which allows targeted action at the vitreoretinal interface without significant retinal toxicity 26. It also causes vitreolysis by its activity on native collagens in the vitreous. Jetrea (ThromboGenics, Inc., Iselin, NJ), the active component of which is ocriplasmin, can be administered via intravitreal injection for pharmacologic vitreolysis. Two large randomized controlled phase 3 clinical trials, MIVI-TRUST (Microplasmin for Intravitreous Injection – Traction Release without Surgical Treatment), compared intravitreal injection of 125 μg/0.1 ml ocriplasmin versus (vs) placebo and found statistically significantly higher rates of resolution of pathology with ocriplasmin injection, including resolution of vitreomacular adhesion in 26.5% vs 10.1% eyes, total posterior vitreous detachment in 13.4% vs 3.7%, macular hole closure in 40.6% vs 10.6% of eyes at day 28, and visual gain ≥ 3 lines occurred in 12.3% vs 6.4% of eyes at month 6 30. Ocular adverse events (usually considered transient) such as floaters, photopsia, injection-related eye pain, or conjunctival hemorrhage occurred in 68.4% vs 53.5% of eyes 30. There have been concerns raised regarding ocular adverse events such as retinal tear/detachment and significant unexplainted short term vision loss which did recover in all cases, although very rare. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Jetrea for the treatment of patients with symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion (i.e. vitreomacular traction) 33 The European Medicines Agency has approved Jetrea for the treatment of patients with vitreomacular traction alone or vitreomacular traction with concurrent full thickness macular hole of diameter ≤ 400 μm 34. It should be noted that vitrectomy may still be required in patients failing ocriplasmin therapy and also in about 20% of the patients successfully treated with ocriplasmin 35.

Other pharmacologic agents that have been investigated include enzymatic agents such as collagenase, chondroitinase, hyaluronidase, dispase, nattokinase, autologous plasmin, plasminogen activators, and non-enzymatic agents such as RGP (arginine-glycine-aspartate) peptides and urea-based Vitreosolve (Vitreoretinal Technologies Inc., Irvine, CA) 36. While many of these have been discredited due to poor efficacy, retinal toxicity, worsening of vitreomacular traction (via vitreous liquefaction without vitreoretinal dehiscence) or persistent need for surgery, some are still being studied 36.

Patients with symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion including macular hole have a poor prognosis if left untreated. Most untreated eyes undergo a further decrease in vision and in some cases progressive complications 37. In patients with symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion who underwent vitrectomy, greater improvement in visual acuity was observed in eyes with better preoperative visual acuity and shorter duration of symptoms 38. Thus, the data suggest that earlier treatment of symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion and related diseases may help in achieving better visual outcome. Nevertheless, the invasiveness, patient inconvenience and complications commonly associated with vitrectomy, often limit its use to patients with advanced disease. Therefore, patients often remain untreated until the condition progressively worsens to a point that warrants surgery.

Observation

A recent spectral domain OCT evolution study by John et al. 39 of ‘symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion’ or vitreomacular traction (VMT) patients showed that over a mean follow-up of 23 months, spontaneous release occurred in 30% of ‘grade 1 vitreomacular adhesion’, 30% of ‘grade 2 vitreomacular adhesion’, and 57% of ‘grade 3 vitreomacular adhesion’ patients, while worsening of spectral domain OCT features occurred in 16% of ‘grade 1 vitreomacular adhesion’, 14% of ‘grade 2 vitreomacular adhesion’ and 28% of ‘grade 3 vitreomacular adhesion’. A higher rate of spontaneous posterior vitreous detachment noted in this natural history study using spectral domain OCT is most likely related to detection and inclusion of patients with early vitreomacular adhesion/vitreomacular traction compared to the previous study by Hikichi et al. using clinical biomicroscopy 39. Based on their spectral domain OCT study, John et al. 39 have suggested that initial observation remains a viable option and may be offered to patients with mild symptoms and vitreomacular adhesion/vitreomacular traction features on spectral domain OCT, before proceeding to surgical or medical treatments.

The natural history of vitreomacular traction syndrome with observation over a median follow-up of 5 years by Hikichi et al. 40 showed that the visual acuity declined by two or more Snellen lines in 64%, cystoid changes persisted in 67%, and new cystoid changes appeared in 17% of the eyes. Resolution of vitreomacular traction by means of a spontaneous complete posterior vitreous detachment was infrequent, occurred in only 11% of eyes at a median duration of 15 months, and was associated with resolution of cystoid changes and visual improvement in them 40. Based on these findings, earlier traction release (as opposed to observation) is recommended for treatment of vitreomacular traction syndrome. Observation may be warranted in rare cases that have spontaneously evolved to complete posterior vitreous detachment and have resolving macular changes (from prior vitreomacular traction) 26.

Disease monitoring

Routine self-assessment by Amsler grid evaluation may be advised for patients with this spectrum of disease identified on routine imaging for other indications.

References- Simpson A. R. H., Petrarca R., Jackson T. L. Vitreomacular adhesion and neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2012;57(6):498–509. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.01.011

- Johnson MW, Brucker AJ, Chang S, et al. Vitreomacular disorders: pathogenesis and treatment. Retina. 2012;32(suppl 2):S173.

- Kang EC, Koh HJ. Effects of Vitreomacular Adhesion on Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:865083. doi:10.1155/2015/865083 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4573628

- Vitreomacular Interface Diseases. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/772188_3

- Sebag J. Anomalous posterior vitreous detachment: a unifying concept in vitreo-retinal disease. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 242(8), 690–698(2004).

- Johnson MW. Posterior vitreous detachment: evolution and complications of its early stages. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 149(3), 371–382(2010).

- Dugel PU. A new focus on the vitreous and its role in retinal function. Retina Today. 2012;4:50–53.

- Vitreomacular Traction Syndrome. https://eyewiki.org/Vitreomacular_Traction_Syndrome

- Reichel E, Jaffe GJ, Sadda SR, et al. Prevalence of vitreomacular adhesion: an optical coherence tomography analysis in the retina clinic setting. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:627-633. Published 2016 Apr 6. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S95524 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4827918

- Schneider EW, Johnson MW. Emerging nonsurgical methods for the treatment of vitreomacular adhesion: a review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1151–1165.

- Jaffe NS. Vitreous traction at the posterior pole of the fundus due to alterations in the vitreous posterior. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1967;71(4):642–652.

- Steel DH, Lotery AJ. Idiopathic vitreomacular traction and macular hole: a comprehensive review of pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Eye (Lond) 2013;27(suppl 1):S1–S21.

- Roldan M, Serrano JM. Macular edema and vitreous detachment. Ann Ophthalmol. 1989;21(4):141–148.

- Nasrallah FP, Jalkh AE, Van CF, et al. The role of the vitreous in diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(10):1335–1339.

- Robison CD, Krebs I, Binder S, et al. Vitreomacular adhesion in active and end-stage age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(1):79–82.

- Jackson TL, Nicod E, Simpson A, Angelis A, Grimaccia F, Kanavos P. Symptomatic vitreomacular adhesion. Retina. 2013;33(8):1503–1511.

- Jackson TL, Nicod E, Angelis A, et al. Vitreous attachment in age-related macular degeneration, diabetic macular edema, and retinal vein occlusion: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Retina. 2013;33:1099–1108.

- Girach A, Pakola S. Vitreomacular interface diseases: pathophysiology, diagnosis and future treatment options. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2012;7(14):311–323.

- Duker JS, Kaiser PK, Binder S, et al. The International Vitreomacular Traction Study Group Classification of Vitreomacular Adhesion, Traction, and Macular Hole. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(12):2611–2619.

- Stalmans P, Duker JS, Kaiser PK, et al. OCT-BASED INTERPRETATION OF THE VITREOMACULAR INTERFACE AND INDICATIONS FOR PHARMACOLOGIC VITREOLYSIS. Retina. 2013.

- Ito Y, Terasaki H, Suzuki T, et al. Mapping posterior vitreous detachment by optical coherence tomography in eyes with idiopathic macular hole. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;135(3):351–5.

- Bottós JM, Elizalde J, Rodrigues EB, Maia M. Current concepts in vitreomacular traction syndrome. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2012;23(3):195–201.

- Johnson MW. Posterior vitreous detachment: evolution and complications of its early stages. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2010;149(3):371–82.e1.

- Spaide RF, Wong D, Fisher Y, Goldbaum M. Correlation of vitreous attachment and foveal deformation in early macular hole states. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2002;133(2):226–9.

- Romano MR, Vallejo-Garcia JL, Camesasca FI, Vinciguerra P, Costagliola C. Vitreo-papillary adhesion as a prognostic factor in pseudo- and lamellar macular holes. Eye (Lond). 2012;26(6):810–5.

- Bottós J, Elizalde J, Arevalo JF, Rodrigues EB, Maia M. Vitreomacular traction syndrome. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 2012;7(2):148–61.

- Chang LK, Fine HF, Spaide RF, Koizumi H, Grossniklaus HE. Ultrastructural correlation of spectral-domain optical coherence tomographic findings in vitreomacular traction syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008;146(1):121–7.

- Gandorfer A, Rohleder M, Kampik A. Epiretinal pathology of vitreomacular traction syndrome. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002;86(8):902–9.

- Stalmans P, Delaey C, de Smet MD, van Dijkman E, Pakola S. Intravit-real injection of microplasmin for treatment of vitreomacular adhesion: results of a prospective, randomized, sham-controlled phase II trial (the MIVI-IIT trial) Retina. 2010;30(7):1122–1127.

- Stalmans P, Benz MS, Gandorfer A, et al. Enzymatic vitreolysis with ocriplasmin for vitreomacular traction and macular holes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367(7):606–15.

- JETREA [package insert] Iselin, NJ: ThromboGenics, Inc; 2014.

- Ponsioen TL, van Luyn MJ a, van der Worp RJ, van Meurs JC, Hooymans JMM, Los LI. Collagen distribution in the human vitreoretinal interface. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008;49(9):4089–95.

- https://www.fda.gov/media/101182/download

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/smop-initial/chmp-summary-positive-opinion-jetrea_en.pdf

- Syed YY, Dhillon S. Ocriplasmin: A Review of Its Use in Patients with Symptomatic Vitreomacular Adhesion. Drugs. 2013:1617–1625.

- Schneider EW, Johnson MW. Emerging nonsurgical methods for the treatment of vitreomacular adhesion: a review. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1151–65.

- Hikichi T, Yoshida A, Trempe CL. Course of vitreomacular traction syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 119(1), 55–61(1995).

- Sebag J. Pharmacologic vitreolysis – premise and promise of the first decade. Retina 29(7), 871–874(2009).

- John VJ, Flynn HW, Smiddy WE, et al. CLINICAL COURSE OF VITREOMACULAR ADHESION MANAGED BY INITIAL OBSERVATION. Retina. 2013.

- Hikichi T, Yoshida A, Trempe CL. Course of vitreomacular traction syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1995;119(1):55–61.