What is bronchitis

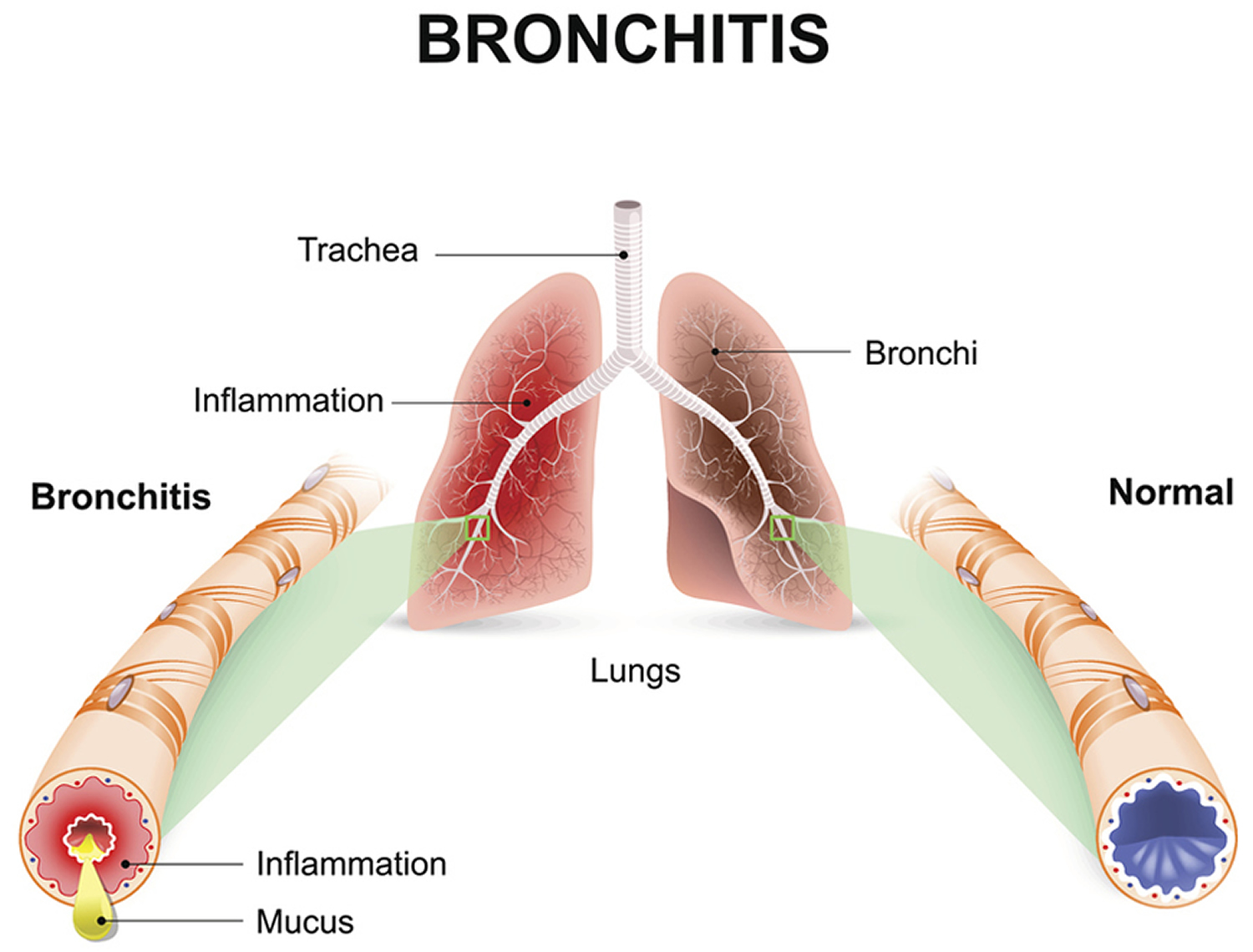

Bronchitis is a condition in which the bronchial tubes become inflamed 1. These tubes carry air to your lungs. People who have bronchitis often have a cough that brings up mucus. Mucus is a slimy substance made by the lining of the bronchial tubes. Bronchitis also may cause wheezing (a whistling or squeaky sound when you breathe), chest pain or discomfort, a low fever, and shortness of breath.

There are two main types of bronchitis, one is acute (short term) and chronic (ongoing) bronchitis.

Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis, often called a “chest cold,” is the most common type of bronchitis 2. Infections or lung irritants cause acute bronchitis. Acute bronchitis is viral in > 95% of cases, often part of a upper respiratory infection. The same viruses that cause colds and the flu are the most common cause of acute bronchitis — rhinovirus, parainfluenza, influenza A or B virus, respiratory syncytial virus, coronavirus, or human metapneumovirus. Less common causes may be Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis, and Chlamydia pneumoniae 3. Less than 5% of cases are caused by bacteria, sometimes in outbreaks 3.

These viruses are spread through the air when people cough. They also are spread through physical contact (for example, on hands that have not been washed).

Acute bronchitis lasts from a few days to 10 days. However, coughing may last for several weeks (normally last less than 3 weeks) after the infection is gone. Antibiotics are not indicated to treat acute bronchitis. Using antibiotics when not needed could do more harm than good.

However, sometimes bacteria can cause acute bronchitis.

Several factors increase your risk for acute bronchitis. Examples include exposure to tobacco smoke (including secondhand smoke), dust, fumes, vapors, and air pollution. Avoiding these lung irritants as much as possible can help lower your risk for acute bronchitis.

Most cases of acute bronchitis go away within a few days. If you think you have acute bronchitis, see your doctor. He or she will want to rule out other, more serious health conditions that require medical care.

What causes acute bronchitis ?

Acute bronchitis is frequently a component of a upper respiratory infection caused by rhinovirus, parainfluenza, influenza A or B virus, respiratory syncytial virus, coronavirus or human metapneumovirus. Less common causes may be Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis, and Chlamydia pneumoniae. Less than 5% of cases are caused by bacteria, sometimes in outbreaks.

Certain substances can irritate your lungs and airways and raise your risk for acute bronchitis. For example, inhaling or being exposed to tobacco smoke, dust, fumes, vapors, or air pollution raises your risk for the condition. These lung irritants also can make symptoms worse.

Being exposed to a high level of dust or fumes, such as from an explosion or a big fire, also may lead to acute bronchitis.

Prevention of acute bronchitis

- Practice good hand hygiene

- Keep you and your child up to date with recommended vaccines

- Don’t smoke and avoid secondhand smoke, chemicals, dust, or air pollution

- Always cover your mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing

- Make sure you and your child are to up-to-date with all recommended vaccine

Who is at Risk for Bronchitis ?

Bronchitis is a very common condition. Millions of cases occur every year.

Elderly people, infants, and young children are at higher risk for acute bronchitis than people in other age groups.

People of all ages can develop chronic bronchitis, but it occurs more often in people who are older than 45. Also, many adults who develop chronic bronchitis are smokers. Women are more than twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with chronic bronchitis.

Smoking and having an existing lung disease greatly increase your risk for bronchitis. Contact with dust, chemical fumes, and vapors from certain jobs also increases your risk for the condition. Examples include jobs in coal mining, textile manufacturing, grain handling, and livestock farming.

Air pollution, infections, and allergies can worsen the symptoms of chronic bronchitis, especially if you smoke.

Symptoms of Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis caused by an infection usually develops after you already have a cold or the flu. Coughing with or without mucus production is the main symptom of acute bronchitis 2. Persistent cough, which may last 10 to 20 days. The cough may produce clear mucus (a slimy substance). If the mucus is yellow or green, you may have a bacterial infection as well. Even after the infection clears up, you may still have a dry cough for days or weeks.

Other symptoms of acute bronchitis include wheezing (a whistling or squeaky sound when you breathe), low fever, and chest tightness or pain.

If your acute bronchitis is severe, you also may have shortness of breath, especially with physical activity.

You may also experience:

- Soreness in the chest

- Fatigue (feeling tired)

- Mild headache

- Mild body aches

- Watery eyes

- Stuffy or runny nose

- Sore throat

- Fever

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

When to Seek Medical Care for acute bronchitis

See a healthcare professional if you or your child have any of the following:

- Temperature higher than 100.4 °F

- Cough with bloody mucus

- Shortness of breath or trouble breathing

- Symptoms that last more than 3 weeks

- Repeated episodes of bronchitis

How Is Bronchitis Diagnosed ?

Your doctor usually will diagnose bronchitis based on your signs and symptoms. He or she may ask questions about your cough, such as how long you’ve had it, what you’re coughing up, and how much you cough.

Your doctor also will likely ask:

- About your medical history

- Whether you’ve recently had a cold or the flu

- Whether you smoke or spend time around others who smoke

- Whether you’ve been exposed to dust, fumes, vapors, or air pollution

Your doctor will use a stethoscope to listen for wheezing (a whistling or squeaky sound when you breathe) or other abnormal sounds in your lungs. He or she also may:

- Look at your mucus to see whether you have a bacterial infection

- Test the oxygen levels in your blood using a sensor attached to your fingertip or toe

- Recommend a chest x ray, lung function tests, or blood tests

Recommended Treatment for Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis almost always gets better on its own—without antibiotics 2. Using antibiotics when they aren’t needed can do more harm than good. Unintended consequences of antibiotics include side effects, like rash and diarrhea, as well as more serious consequences, such as an increased risk for an antibiotic-resistant infection or Clostridium difficle infection, a sometimes deadly diarrhea.

Antibiotics usually aren’t prescribed for acute bronchitis. This is because they don’t work against viruses—the most common cause of acute bronchitis. However, if your doctor thinks you have a bacterial infection, he or she may prescribe antibiotics.

Evidence supporting efficacy of routine use of other symptomatic treatments, such as antitussives (drugs that suppresses coughing), mucolytics (drugs that are able to break down mucus) and bronchodilators 4, is weak 3. Antitussives should be considered only if the cough is interfering with sleep 3. Patients with wheezing may benefit from an inhaled β2-agonist (eg, albuterol) or an anticholinergic (eg, ipratropium) for a few days 3. Oral antibiotics are typically not used except in patients with pertussis or during known outbreaks of bacterial infection. A macrolide such as azithromycin 500 mg po once, then 250 mg po once/day for 4 days or clarithromycin 500 mg po bid for 14 days is given 3.

Home remedies for acute bronchitis:

- Get plenty of rest

- Drink plenty of fluids

- Use a clean humidifier or cool mist vaporizer

- Breathe in steam from a bowl of hot water or shower

- Use lozenges (do not give lozenges to children younger than 4 years of age)

- Aspirin (for adults) or acetaminophen to treat fever

- Ask your healthcare professional or pharmacist about over-the-counter medicines that can help you feel better.

Remember, always use over-the-counter medicines as directed. Do not use cough and cold medicines in children younger than 4 years of age unless specifically told to do so by a healthcare professional.

Your healthcare professional will most likely prescribe antibiotics for a diagnosis of whooping cough (pertussis) or pneumonia.

Chronic Bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis is defined as productive cough on most days of the week for at least 3 months total duration in 2 successive years 5. Chronic bronchitis becomes chronic obstructive bronchitis if spirometric evidence of airflow obstruction develops. Chronic asthmatic bronchitis is a similar, overlapping condition characterized by chronic productive cough, wheezing, and partially reversible airflow obstruction; it occurs predominantly in smokers with a history of asthma. In some cases, the distinction between chronic obstructive bronchitis and chronic asthmatic bronchitis is unclear and may be referred to as asthma chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap syndrome (ACOS) 5.

Chronic bronchitis is an ongoing, serious condition. It occurs if the lining of the bronchial tubes is constantly irritated and inflamed, causing a long-term cough with mucus. Smoking is the main cause of chronic bronchitis.

Viruses or bacteria can easily infect the irritated bronchial tubes. If this happens, the condition worsens and lasts longer. As a result, people who have chronic bronchitis have periods when symptoms get much worse than usual.

Chronic bronchitis is a serious, long-term medical condition. Early diagnosis and treatment, combined with quitting smoking and avoiding secondhand smoke, can improve quality of life. The chance of complete recovery is low for people who have severe chronic bronchitis.

In the US, about 24 million people have airflow limitation, of whom about 12 million have a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the 3rd leading cause of death, resulting in 135,000 deaths in 2010—compared with 52,193 deaths in 1980. From 1980 to 2000, the COPD mortality rate increased 64% (from 40.7 to 66.9/100,000) and has remained steady since then 5. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality rates increase with age. Prevalence is now higher in women, but total mortality is similar in both sexes. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) seems to aggregate in families independent of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (alpha-1antiprotease inhibitor deficiency).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is increasing worldwide because of the increase in smoking in developing countries, the reduction in mortality due to infectious diseases, and the widespread use of biomass fuels such as wood, grasses, or other organic materials. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) mortality may also affect developing nations more than developed nations. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects 64 million people and caused > 3 million deaths worldwide in 2005 and is projected to become the 3rd leading cause of death globally by the year 2030.

What causes chronic bronchitis ?

Repeatedly breathing in fumes that irritate and damage lung and airway tissues causes chronic bronchitis. Smoking is the major cause of the condition.

Breathing in air pollution and dust or fumes from the environment or workplace also can lead to chronic bronchitis.

People who have chronic bronchitis go through periods when symptoms become much worse than usual. During these times, they also may have acute viral or bacterial bronchitis.

Inhalational exposure

Of all inhalational exposures, cigarette smoking is the primary risk factor in most countries, although only about 15% of smokers develop clinically apparent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); an exposure history of 40 or more pack-years is especially predictive. Smoke from indoor cooking and heating is an important causative factor in developing countries. Smokers with preexisting airway reactivity (defined by increased sensitivity to inhaled methacholine), even in the absence of clinical asthma, are at greater risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) than are those without.

Low body weight, childhood respiratory disorders, and exposure to passive cigarette smoke, air pollution, and occupational dust (eg, mineral dust, cotton dust) or inhaled chemicals (eg, cadmium) contribute to the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) but are of minor importance compared with cigarette smoking.

Genetic factors

The best-defined causative genetic disorder is alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, which is an important cause of emphysema in nonsmokers and influences susceptibility to disease in smokers.

In recent years, > 30 genetic variants have been found to be associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or decline in lung function in selected populations, but none has been shown to be as consequential as alpha-1 antitrypsin.

Pathophysiology of Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Various factors cause the airflow limitation and other complications of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Inflammation

Inhalational exposures can trigger an inflammatory response in airways and alveoli that leads to disease in genetically susceptible people. The process is thought to be mediated by an increase in protease activity and a decrease in antiprotease activity. Lung proteases, such as neutrophil elastase, matrix metalloproteinases, and cathepsins, break down elastin and connective tissue in the normal process of tissue repair. Their activity is normally balanced by antiproteases, such as alpha-1 antitrypsin, airway epithelium–derived secretory leukoproteinase inhibitor, elafin, and matrix metalloproteinase tissue inhibitor. In patients with COPD, activated neutrophils and other inflammatory cells release proteases as part of the inflammatory process; protease activity exceeds antiprotease activity, and tissue destruction and mucus hypersecretion result.

Neutrophil and macrophage activation also leads to accumulation of free radicals, superoxide anions, and hydrogen peroxide, which inhibit antiproteases and cause bronchoconstriction, mucosal edema, and mucous hypersecretion. Neutrophil-induced oxidative damage, release of profibrotic neuropeptides (eg, bombesin), and reduced levels of vascular endothelial growth factor may contribute to apoptotic destruction of lung parenchyma.

The inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) increases as disease severity increases, and, in severe (advanced) disease, inflammation does not resolve completely despite smoking cessation. This chronic inflammation does not seem to respond to corticosteroids.

Infection

Respiratory infection (which COPD patients are prone to) may amplify progression of lung destruction.

Bacteria, especially Haemophilus influenzae, colonize the lower airways of about 30% of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In more severely affected patients (eg, those with previous hospitalizations), colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa or other gram-negative bacteria is common. Smoking and airflow obstruction may lead to impaired mucus clearance in lower airways, which predisposes to infection. Repeated bouts of infection increase the inflammatory burden that hastens disease progression. There is no evidence, however, that long-term use of antibiotics slows the progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Airflow limitation

The cardinal pathophysiologic feature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is airflow limitation caused by airway narrowing and/or obstruction, loss of elastic recoil, or both.

Airway narrowing and obstruction are caused by inflammation-mediated mucus hypersecretion, mucus plugging, mucosal edema, bronchospasm, peribronchial fibrosis, and destruction of small airways or a combination of these mechanisms. Alveolar septa are destroyed, reducing parenchymal attachments to the airways and thereby facilitating airway closure during expiration.

Enlarged alveolar spaces sometimes consolidate into bullae, defined as airspaces ≥ 1 cm in diameter. Bullae may be entirely empty or have strands of lung tissue traversing them in areas of locally severe emphysema; they occasionally occupy the entire hemithorax. These changes lead to loss of elastic recoil and lung hyperinflation.

Increased airway resistance increases the work of breathing. Lung hyperinflation, although it decreases airway resistance, also increases the work of breathing. Increased work of breathing may lead to alveolar hypoventilation with hypoxia and hypercapnia, although hypoxia is also caused by ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch.

Complications of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

In addition to airflow limitation and sometimes respiratory insufficiency, complications include

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Respiratory infection

- Weight loss and other comorbidities

Chronic hypoxemia increases pulmonary vascular tone, which, if diffuse, causes pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale. The increase in pulmonary vascular pressure may be augmented by the destruction of the pulmonary capillary bed due to destruction of alveolar septa.

Viral or bacterial respiratory infections are common among patients with COPD and cause a large percentage of acute exacerbations. It is currently thought that acute bacterial infections are due to acquisition of new strains of bacteria rather than overgrowth of chronic colonizing bacteria.

Weight loss may occur, perhaps in response to decreased caloric intake and increased levels of circulating tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha.

Other coexisting or complicating disorders that adversely affect quality of life and survival include osteoporosis, depression, anxiety, coronary artery disease, lung cancer and other cancers, muscle atrophy, and gastroesophageal reflux. The extent to which these disorders are consequences of COPD, smoking, and the accompanying systemic inflammation is unclear.

Signs and symptoms of chronic bronchitis

The signs and symptoms of chronic bronchitis include coughing, wheezing, and chest discomfort. The coughing may produce large amounts of mucus. This type of cough often is called a smoker’s cough.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) takes years to develop and progress.

- Most patients have smoked ≥ 20 cigarettes/day for > 20 yr.

- Productive cough usually is the initial symptom, developing among smokers in their 40s and 50s.

- Dyspnea (difficult or laboured breathing) that is progressive, persistent, exertional, or worse during respiratory infection appears when patients are in their late 50s or 60s.

Symptoms usually progress quickly in patients who continue to smoke and in those who have a higher lifetime tobacco exposure. Morning headache develops in more advanced disease and signals nocturnal hypercapnia or hypoxemia.

Signs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) include wheezing, a prolonged expiratory phase of breathing, lung hyperinflation manifested as decreased heart and lung sounds, and increased anteroposterior diameter of the thorax (barrel chest). Patients with advanced emphysema lose weight and experience muscle wasting that has been attributed to immobility, hypoxia, or release of systemic inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-alpha.

Signs of advanced disease include pursed-lip breathing, accessory respiratory muscle use, paradoxical inward movement of the lower intercostal interspaces during inspiration (Hoover sign), and cyanosis. Signs of cor pulmonale include neck vein distention, splitting of the 2nd heart sound with an accentuated pulmonic component, tricuspid insufficiency murmur, and peripheral edema. Right ventricular heaves are uncommon in COPD because the lungs are hyperinflated.

Spontaneous pneumothorax may occur (possibly related to rupture of bullae) and should be suspected in any patient with COPD whose pulmonary status abruptly worsens.

Acute exacerbations

Acute exacerbations occur sporadically during the course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and are heralded by increased symptom severity. The specific cause of any exacerbation is almost always impossible to determine, but exacerbations are often attributed to viral URIs, acute bacterial bronchitis, or exposure to respiratory irritants. As chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) progresses, acute exacerbations tend to become more frequent, averaging about 1 to 3 episodes/yr.

How is Chronic Bronchitis Treated ?

The main goals of treating chronic bronchitis are to relieve symptoms and make breathing easier.

A humidifier or steam can help loosen mucus and relieve wheezing and limited air flow. If your bronchitis causes wheezing, you may need an inhaled medicine to open your airways. You take this medicine using an inhaler. This device allows the medicine to go straight to your lungs.

Your doctor also may prescribe medicines to relieve or reduce your cough and treat your inflamed airways (especially if your cough persists).

If you have chronic bronchitis and also have been diagnosed with COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), you may need medicines to open your airways and help clear away mucus. These medicines include bronchodilators (inhaled) and steroids (inhaled or pill form).

If you have chronic bronchitis, your doctor may prescribe oxygen therapy. This treatment can help you breathe easier, and it provides your body with needed oxygen.

One of the best ways to treat acute and chronic bronchitis is to remove the source of irritation and damage to your lungs. If you smoke, it’s very important to quit.

Talk with your doctor about programs and products that can help you quit smoking. Try to avoid secondhand smoke and other lung irritants, such as dust, fumes, vapors, and air pollution.

How Can Bronchitis Be Prevented ?

You can’t always prevent acute or chronic bronchitis. However, you can take steps to lower your risk for both conditions. The most important step is to quit smoking or not start smoking.

Also, try to avoid other lung irritants, such as secondhand smoke, dust, fumes, vapors, and air pollution. For example, wear a mask over your mouth and nose when you use paint, paint remover, varnish, or other substances with strong fumes. This will help protect your lungs.

Wash your hands often to limit your exposure to germs and bacteria. Your doctor also may advise you to get a yearly flu shot and a pneumonia vaccine.

Prognosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Severity of airway obstruction predicts survival in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The mortality rate in patients with an FEV1 ≥ 50% of predicted is slightly greater than that of the general population. If the FEV1 is 0.75 to 1.25 L, 5-yr survival is about 40 to 60%; if < 0.75 L, about 30 to 40%.

More accurate prediction of death risk is possible by simultaneously measuring body mass index (B), the degree of airflow obstruction (O, which is the FEV1), dyspnea (D, which is measured using Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC Questionnaire), and exercise capacity (E, which is measured with a 6-min walking test); this is the BODE index.

Table 1. Breathlessness Measurement using the Modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) Questionnaire

Grade | Shortness of Breath |

0 | None except during strenuous exercise |

1 | Occurring when hurrying on level ground or walking up a slight incline |

2 | Resulting in walking more slowly than people of the same age on level ground or Resulting in stopping for breath when walking at own pace on level ground |

3 | Resulting in stopping for breath after walking about 100 meters or after a few minutes on level ground |

4 | Severe enough to prevent the person from leaving the house or Occurring when dressing or undressing |

Also, older age, heart disease, anemia, resting tachycardia, hypercapnia, and hypoxemia decrease survival, whereas a significant response to bronchodilators predicts improved survival. Risk factors for death in patients with acute exacerbation requiring hospitalization include older age, higher Paco2, and use of maintenance oral corticosteroids.

Patients at high risk of imminent death are those with progressive unexplained weight loss or severe functional decline (eg, those who experience dyspnea with self-care, such as dressing, bathing, or eating). Mortality in COPD may result from intercurrent illnesses rather than from progression of the underlying disorder in patients who have stopped smoking. Death is generally caused by acute respiratory failure, pneumonia, lung cancer, heart disease, or pulmonary embolism.

Living With Chronic Bronchitis

If you have chronic bronchitis, you can take steps to control your symptoms. Lifestyle changes and ongoing care can help you manage the condition.

Lifestyle Changes

The most important step is to not start smoking or to quit smoking. Talk with your doctor about programs and products that can help you quit.

Also, try to avoid other lung irritants, such as secondhand smoke, dust, fumes, vapors, and air pollution. This will help keep your lungs healthy.

Wash your hands often to lower your risk for a viral or bacterial infection. Also, try to stay away from people who have colds or the flu. See your doctor right away if you have signs or symptoms of a cold or the flu.

Follow a healthy diet and be as physically active as you can. A healthy diet includes a variety of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. It also includes lean meats, poultry, fish, and fat-free or low-fat milk or milk products. A healthy diet also is low in saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, sodium (salt), and added sugar.

Ongoing Care

See your doctor regularly and take all of your medicines as prescribed. Also, talk with your doctor about getting a yearly flu shot and a pneumonia vaccine.

If you have chronic bronchitis, you may benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation. Pulmonary rehabilitation is a broad program that helps improve the well-being of people who have chronic (ongoing) breathing problems.

People who have chronic bronchitis often breathe fast. Talk with your doctor about a breathing method called pursed-lip breathing. This method decreases how often you take breaths, and it helps keep your airways open longer. This allows more air to flow in and out of your lungs so you can be more physically active.

To do pursed-lip breathing, you breathe in through your nostrils. Then you slowly breathe out through slightly pursed lips, as if you’re blowing out a candle. You exhale two to three times longer than you inhale. Some people find it helpful to count to two while inhaling and to four or six while exhaling.

References- What Is Bronchitis ? National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/brnchi

- Preventing and Treating Bronchitis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/for-patients/common-illnesses/bronchitis.html

- Acute Bronchitis. Merck Manual. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pulmonary-disorders/acute-bronchitis/acute-bronchitis

- drugs that cause widening of the bronchi

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Merck Manual. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pulmonary-disorders/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-and-related-disorders/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd