White sponge nevus

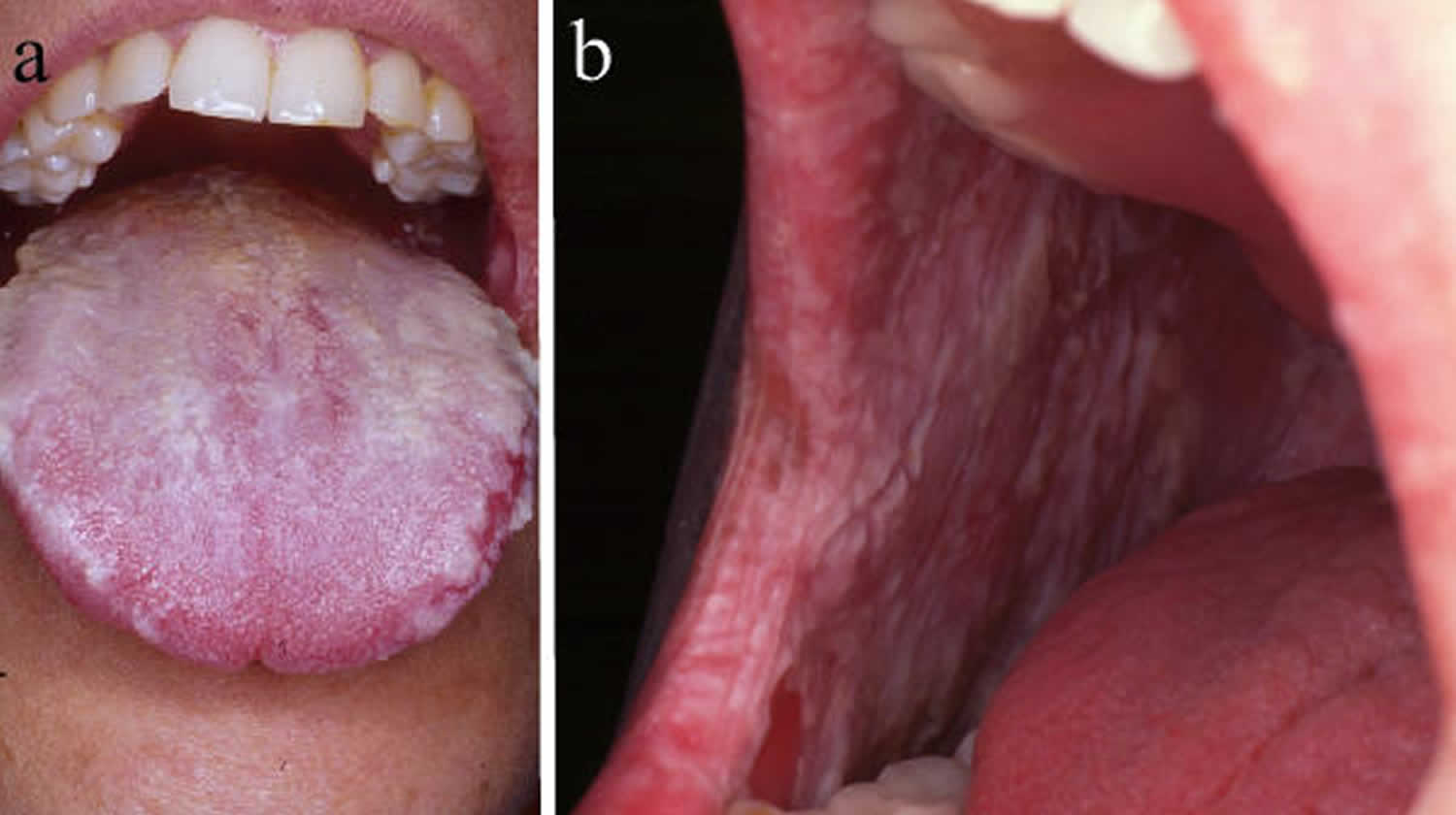

White sponge nevus or oral white sponge naevus, is a rare benign genetic condition that causes the formation of white patches of tissue called nevus that appear as thickened, velvety, sponge-like tissue of the mucous membranes, most commonly found on the moist lining of the mouth (oral mucosa), especially on the inside of the cheeks (buccal mucosa) and less frequently nasal, esophageal, rectal, and genital mucosa 1. Affected individuals usually develop multiple nevi. White sponge nevus has also been called WSN, congenital leukokeratosis, familial white folded mucosal dysplasia, leukoderma exfoliativum mucosae oris, hereditary leukokeratosis, white folded gingivostomatitis, oral epithelial nevus, nevus of Cannon or white sponge nevus of Cannon 2. Oral white sponge nevus appears as white or gray diffuse plaques thickened with multiple furrows and spongy texture located onbuccal, labial, gingival mucosa and floor of the mouth 3.

White sponge nevus is a benign, uncommon, autosomal dominant disorder that involves a mutation in mucosal keratin that predominantly affects non-keratinized stratified-squamous epithelia 4. The exact prevalence of white sponge nevus is unknown, but it is estimated to affect less than 1 in 200,000 individuals worldwide 5.

White sponge nevus can be present from birth but usually first appears during early childhood, with 50 percent of patients being diagnosed before age 20 6 and showed no gender preference 7. The size and location of white sponge nevus can change over time 5. In the oral mucosa, both sides of the mouth are usually affected. White sponge nevus are generally painless, but the folds of extra tissue can promote bacterial growth, which can lead to infection that may cause discomfort. The altered texture and appearance of the affected tissue, especially the oral mucosa, can be bothersome for some affected individuals. There have been no reports of oral cancer developing in a white sponge nevus. However, Downham and Plezia 8 reported the occurrence of an oral squamous-cell carcinoma within a white sponge nevus. This malignant transformation might be induced by chronic prednisone use, and no other similar cases were reported 8.

No treatment required in case of asymptomatic oral white sponge nevus and no standard treatment for the condition exists 9. Various molecules were tested to reduce the clinical presentation of the white sponge nevus. These include beta-carotene, antibiotics (penicillin, azithromycin, etc.), antifungal therapy 10, antihistamines, local applications of retinoic acid 11, tetracycline mouth rinses 12, surgical resection, and laser ablation, but without any success 13.

Although oral white sponge nevus is painless, patients may complain of an altered texture of the mucosa or that lesions are not aesthetic. There may be periods of exacerbation and remission; typically, no treatment is sought by patients. Generally, progression of oral white sponge nevus stops at puberty and there is no malignant transformation 14. Reassurance is all that is required.

Figure 1. White sponge nevus

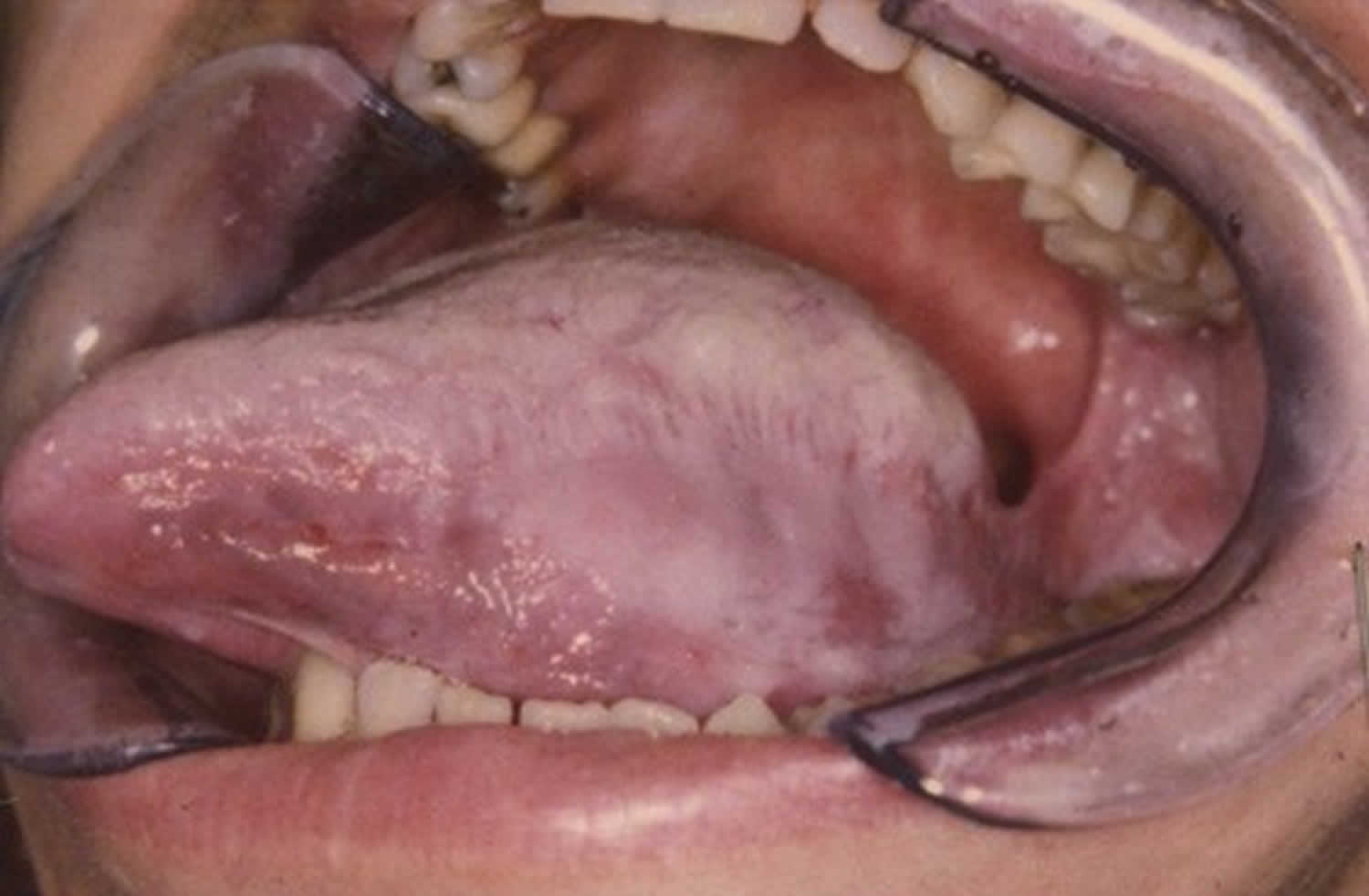

Figure 2. White sponge nevus tongue

White sponge nevus causes

Mutations in the Keratin 4 (KRT4) or Keratin 13 (KRT13) gene cause white sponge nevus. These genes provide instructions for making proteins called keratins. Keratins are a group of tough, fibrous proteins that form the structural framework of epithelial cells, which are cells that line the surfaces and cavities of the body and make up the different mucosae. The keratin 4 protein (produced from the KRT4 gene) and the keratin 13 protein (produced from the KRT13 gene) partner together to form molecules known as intermediate filaments. These filaments assemble into networks that provide strength and resilience to the different mucosae. Networks of intermediate filaments protect the mucosae from being damaged by friction or other everyday physical stresses.

Mutations in the KRT4 or KRT13 gene disrupt the structure of the keratin protein 15. As a result, keratin 4 and keratin 13 are mismatched and do not fit together properly, leading to the formation of irregular intermediate filaments that are easily damaged with little friction or trauma. Fragile intermediate filaments in the oral mucosa might be damaged when eating or brushing one’s teeth. Damage to intermediate filaments leads to inflammation and promotes the abnormal growth and division (proliferation) of epithelial cells, causing the mucosae to thicken and resulting in white sponge nevus.

White sponge nevus inheritance pattern

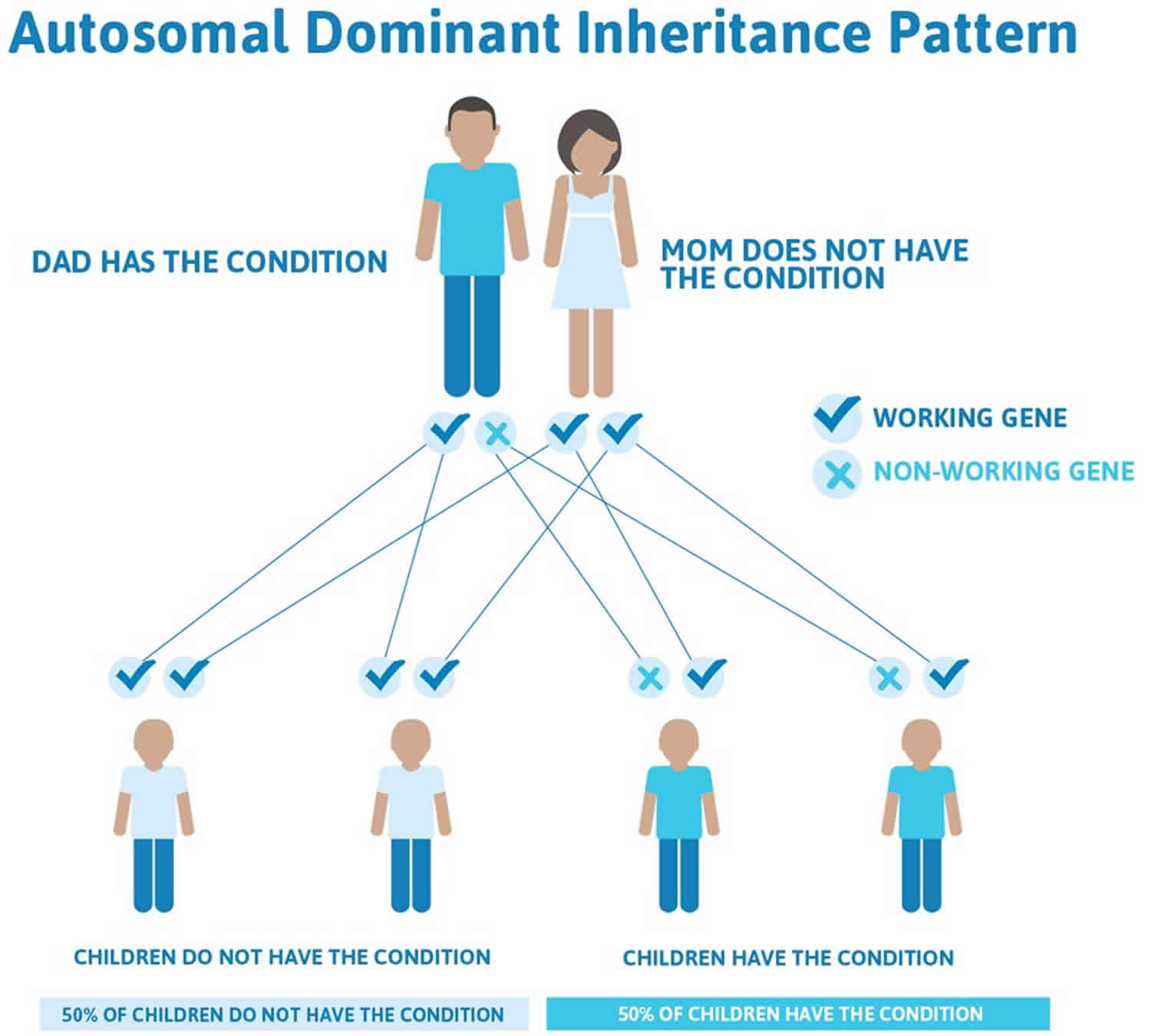

White sponge nevus is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, which means one copy of the altered gene in each cell can be sufficient to cause the disorder. However, some people who have a mutation that causes white sponge nevus do not develop these abnormal growths; this phenomenon is called reduced penetrance.

Cases without a familial background have been reported 16. Liu et al. 17 have recently compared sporadic and familial cases of white sponge nevus and concluded that only one of the five sporadic cases had keratin mutation.

Often autosomal dominant conditions can be seen in multiple generations within the family. If one looks back through their family history they notice their mother, grandfather, aunt/uncle, etc., all had the same condition. In cases where the autosomal dominant condition does run in the family, the chance for an affected person to have a child with the same condition is 50% regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

- When one parent has the abnormal gene, they will pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. Each of their children therefore has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting the changed gene and being affected by the condition.

- There is also a 50% (1 in 2) chance that a child will inherit the normal copy of the gene. If this happens the child will not be affected by the disorder and cannot pass it on to any of his or her children.

Figure 3 illustrates autosomal dominant inheritance. The example below shows what happens when dad has the condition, but the chances of having a child with the condition would be the same if mom had the condition.

Figure 3. White sponge nevus autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

White sponge nevus differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of oral white sponge nevus in childhood is made with other conditions presenting as white lesions on the oral mucosa 18. These include other congenital disorders such as leukoedema, follicular keratosis, dyskeratosis congenita, hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis, and oral lesions of pachyonychia congenita and Darier disease 1. The acquired conditions include focal epithelial hyperplasia and oral florid papillomatosis associated with human papillomavirus. Most commonly white sponge nevus is misdiagnosed as oral candidiasis (thrush). A clue on clinical examination is that the white patches of candidiasis can be peeled off. This diagnosis is excluded by fungal examination and responsiveness to antifungal agents. Oral lichen planus may also be confused with an oral white sponge nevus, but this disorder is less common in young people and is readily distinguished on biopsy 18.

White sponge nevus symptoms

White sponge nevus is seen usually in oral mucosa bilaterally as symmetrical, thickened, white, velvety, diffuse plaques that affect the buccal mucosa. The affected mucosa may appear folded and it feels spongy, not hard 19. It cannot be detached. The change may be quite subtle and localized or can involve the entire inside of the mouth. The less common intraoral location of white sponge nevus includes the tongue, labial mucosa, soft palate, alveolar mucosa, and floor of the mouth 20.

White sponge nevus usually does not cause any symptoms, but patients may complain of roughness and of the appearance.

The mouth is the commonest site affected and the insides of the cheeks the most common site within the mouth. However the mucous membranes of inside the nose, the esophagus, the genitalia (vulva and vagina) and anorectal sites can also be involved. Usually the mouth is the first site noticed.

No changes are noticed elsewhere on the skin, nails, hair or teeth. This is important when considering other possible causes of the lesions.

White sponge nevus diagnosis

The combination of the clinical appearance, the absence of any other skin problems and a positive family history should raise the possibility of white sponge nevus diagnosis which is then confirmed on biopsy of the lesion and pathology examination. The histopathology of white sponge nevus is very characteristic and in particular shows extensive areas of large clear skin cells in the epidermis. The histological features include acanthosis, hyperparakeratosis, and vacuolization of keratinocytes with a characteristic perinuclear eosinophilic condensation which is not necessarily pathognomonic 13.

The diagnosis can now be made definitively on genetic analysis and identification of a mutation in a highly conserved sequence of one copy of the gene coding for the keratin 4 or 13 proteins.

Many other genetic conditions may show white patches in the mouth, but these can usually be excluded on clinical examination as they all have visible changes elsewhere on the skin, nails, etc. These include pachyonychia congenita, Darier disease, dyskeratosis congenita and hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis.

Most commonly white sponge nevus is misdiagnosed as oral candidiasis (thrush) but this can be excluded on microbiological swabs, failure to respond to antifungal treatment and biopsy. A clue on clinical examination is that the white patches of candidiasis can be peeled off.

The second most common misdiagnosis is oral lichen planus and this is readily distinguished on biopsy.

Other causes of localized white patches in the mouth that may cause confusion include leukoplakia, cheek biting, chewing of tobacco or betel nut (oral submucous fibrosis), syphilis and lupus erythematosus. Again, the pathology of a biopsy will clarify this.

White sponge nevus treatment

One of the important reasons for making this diagnosis is to avoid unnecessary treatment. In general, explanation and reassurance are all that is required.

When treatment is requested there have been some reports of successful control using topical or systemic antibiotics:

- tetracycline mouthwash – 0.25% aqueous tetracycline solution, 5ml twice daily.

- tetracycline orally – initially 250mg, four times daily for 4 weeks followed by 250mg once each week to maintain the response

- amoxycillin orally – initially 250mg three times daily for 4 weeks followed by 250mg once each week to maintain the improvement.

- erythromycin may help should tetracycline and amoxycillin be inappropriate due to allergy.

These are not curative, but may sometimes induce either a complete or partial remission which may be maintained by continuing with a low dose. When the antibiotic is ceased, the condition recurs, usually after weeks or months. Why these antibiotics should help some patients is unclear.

Many other treatments have been tried unsuccessfully including topical antifungal agents, oral antifungal therapies, retinoids such as acitretin and isotretinoin, vitamins and other antibiotics such as metronidazole and trimethoprim + sulphamethoxazole.

References- Elfatoiki FZ, Capatas S, Skali HD, Hali F, Attar H, Chiheb S. Oral White Sponge Nevus: An Exceptional Differential Diagnosis in Childhood. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:9296768. Published 2020 Aug 26. doi:10.1155/2020/9296768 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7471808

- Cannon AB. White sponge nevus of the mucosa (naevus spongiosus albus mucosae) Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1935;31:365.

- Regezi J. A., Scuibba J. J., Jordan R. C. Oral Pathology Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 6th. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Saunders Elsevier; 2012. pp. 80–81.

- Epidermal nevi, neoplasms and cysts. In: Odom RB, et al., eds. Andrews Diseases of the Skin Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000: 815

- White sponge nevus. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/white-sponge-nevus

- Woo S-B. Diseases of the oral mucosa. In: Mckee PH, et al., eds. Pathology of the Skin with Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby, 2005:387

- Quintella C., Janson G., Azevedo L. R., Damante J. H. Orthodontic therapy in a patient with white sponge nevus. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2004;125(4):497–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.07.003

- Downham T. F., Jr., Plezia R. A. Oral squamous-cell carcinoma within a white-sponge nevus. The Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1978;4(6):470–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1978.tb00476.x

- Everett FG, Noyes HJ. White folded gingivostomatitis. J Periodontol 1953;24:32

- O’Leary PA, et al. White sponge naevus: moniliasis? Arch Dermatol Syphilol 1950;62:608

- Aloi FG, Moliners A. White sponge nevus with epidermolytic changes. Dermatologica 1988;177:323

- Lamey PJ, et al. Oral white naevus: responds to antibiotic therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol 1998;23:59

- Sanjeeta N., Nandini D., Premlata T., Banerjee S. White sponge nevus: report of three cases in a single family. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2016;20(2):300–303. doi: 10.4103/0973-029x.185915

- Lamey PJ, et al. Oral White sponge naevus: response to antibiotic therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol 1998;23:59

- Shibuya Y., Zhang J., Yokoo S., Umeda M., Komori T. Constitutional mutation of keratin 13 gene in familial white sponge nevus. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2003;96(5):561–565. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00372-x

- Part 2: Developmental abnormalities. In: Rushton MA, Cooke BED. Oral Histopathology. Edinburgh: Livingstone, 1963: 140

- Liu X., Li Q., Gao Y., Song S., Hua H. Mutational analysis in familial and sporadic patients with white sponge naevus. British Journal of Dermatology. 2011;165(2):448–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10404.x

- Sobhan M., Alirezaei P., Farshchian M., Eshghi G, Ghasemi Basir H. R, Khezrian L. White sponge nevus: report of a case and review of the literature. Acta Medica Iranica. 2017;55(8):533–535.

- Rajendran R. Diseases of the skin. In: Rajendran R., Sivapathasundharam B., editors. Shafer’s Textbook of Oral Pathology. 7th. New Delhi, India: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 821–822.

- Neville B. W., Damn D. D., Allen C. M., et al. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Elsevier; 2002.