Childhood vaccinations

Vaccination is the term used for getting a vaccine, that is, actually getting the injection or taking an oral vaccine dose. Vaccines train your immune system to quickly recognize and clear out germs (bacteria and viruses) that can cause serious illnesses. Vaccines strengthen your immune system a bit like exercise strengthens muscles. Below is the Recommended Child and Adolescent Immunization Schedule for ages 18 years or younger, United States, 2022. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine vaccination or immunization to prevent 17 vaccine-preventable diseases that occur in infants, children, adolescents, or adults. The schedules shown below is recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/index.html) and approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov), American Academy of Pediatrics (https://www.aap.org/en-us/Pages/Default.aspx), American Academy of Family Physicians (https://www.aafp.org/home.html), American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (https://www.acog.org), and American College of Nurse-Midwives (https://www.midwife.org/default.aspx).

Diphtheria (Can be prevented by Tdap vaccination)

Diphtheria is a very contagious bacterial disease that affects the respiratory system, including the lungs. Diphtheria bacteria can be spread from person to person by direct contact with droplets from an infected person’s cough or sneeze. When people are infected, the bacteria can produce a toxin (poison) in the body that can cause a thick coating in the back of the nose or throat that makes it hard to breathe or swallow. Effects from this toxin can also lead to swelling of the heart muscle and, in some cases, heart failure. In serious cases, the illness can cause coma, paralysis, or even death.

Hepatitis A (Can be prevented by HepA vaccination)

Hepatitis A is an infection in the liver caused by hepatitis A virus. The virus is spread primarily person-to-person through the fecal-oral route. In other words, the virus is taken in by mouth from contact with objects, food, or drinks contaminated by the feces (stool) of an infected person. Symptoms can include fever, tiredness, poor appetite, vomiting, stomach pain, and sometimes jaundice (when skin and eyes turn yellow). An infected person may have no symptoms, may have mild illness for a week or two, may have severe illness for several months, or may rarely develop liver failure and die from the infection. In the U.S., about 100 people a year die from hepatitis A.

Hepatitis B (Can be prevented by HepB vaccination)

Hepatitis B causes a flu-like illness with loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, rashes, joint pain, and jaundice. Symptoms of acute hepatitis B include fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, pain in joints and stomach, dark urine, grey-colored stools, and jaundice (when skin and eyes turn yellow).

Human Papillomavirus (Can be prevented by HPV vaccination)

Human papillomavirus is a common virus. HPV is most common in people in their teens and early 20s. About 14 million people, including teens, become infected with HPV each year. HPV infection can cause cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancers in women and penile cancer in men. HPV can also cause anal cancer, oropharyngeal cancer (back of the throat), and genital warts in both men and women.

Influenza (Can be prevented by annual flu vaccination)

Influenza is a highly contagious viral infection of the nose, throat, and lungs. The virus spreads easily through droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes and can cause mild to severe illness. Typical symptoms include a sudden high fever, chills, a dry cough, headache, runny nose, sore throat, and muscle and joint pain. Extreme fatigue can last from several days to weeks. Influenza may lead to hospitalization or even death, even among previously healthy children.

Measles (Can be prevented by MMR vaccination)

Measles is one of the most contagious viral diseases. Measles virus is spread by direct contact with the airborne respiratory droplets of an infected person. Measles is so contagious that just being in the same room after a person who has measles has already left can result in infection. Symptoms usually include a rash, fever, cough, and red, watery eyes. Fever can persist, rash can last for up to a week, and coughing can last about 10 days. Measles can also cause pneumonia, seizures, brain damage, or death.

Meningococcal Disease (Can be prevented by meningococcal vaccination)

Meningococcal disease has two common outcomes: meningitis (infection of the lining of the brain and spinal cord) and bloodstream infections. The bacteria that cause meningococcal disease spread through the exchange of nose and throat droplets, such as when coughing, sneezing, or kissing. Symptoms include sudden onset of fever, headache, and stiff neck. With bloodstream infection, symptoms also include a dark purple rash. About one of every ten people who gets the disease dies from it. Survivors of meningococcal disease may lose their arms or legs, become deaf, have problems with their nervous systems, become developmentally disabled, or suffer seizures or strokes.

Mumps (Can be prevented by MMR vaccination)

Mumps is an infectious disease caused by the mumps virus, which is spread in the air by a cough or sneeze from an infected person. A child can also get infected with mumps by coming in contact with a contaminated object, like a toy. The mumps virus causes swollen salivary glands under the ears or jaw, fever, muscle aches, tiredness, abdominal pain, and loss of appetite. Severe complications for children who get mumps are uncommon, but can include meningitis (infection of the covering of the brain and spinal cord), encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), permanent hearing loss, or swelling of the testes, which rarely results in decreased fertility.

Pertussis (Whooping Cough) (Can be prevented by Tdap vaccination)

Pertussis spreads very easily through coughing and sneezing. It can cause a bad cough that makes someone gasp for air after coughing fits. This cough can last for many weeks, which can make preteens and teens miss school and other activities. Pertussis can be deadly for babies who are too young to receive the vaccine. Often babies get whooping cough from their older brothers or sisters, like preteens or teens, or other people in the family. Babies with pertussis can get pneumonia, have seizures, become brain damaged, or even die. About half of children under 1 year of age who get pertussis must be hospitalized.

Pneumococcal Disease (Can be prevented by pneumococcal vaccination)

Pneumonia is an infection of the lungs that can be caused by the bacteria called pneumococcus. These bacteria can cause other types of infections too, such as ear infections, sinus infections, meningitis (infection of the lining of the brain and spinal cord), and bloodstream infections. Sinus and ear infections are usually mild and are much more common than the more serious forms of pneumococcal disease. However, in some cases pneumococcal disease can be fatal or result in long-term problems, like brain damage, and hearing loss. The bacteria that cause pneumococcal disease spread when people cough or sneeze. Many people have the bacteria in their nose or throat at one time or another without being ill—this is known as being a carrier.

Polio (Can be prevented by IPV vaccination)

Polio is caused by a virus that lives in an infected person’s throat and intestines. It spreads through contact with the stool of an infected person and through droplets from a sneeze or cough. Symptoms typically include sore throat, fever, tiredness, nausea, headache, or stomach pain. In about 1% of cases, polio can cause paralysis. Among those who are paralyzed, About 2 to 10 children out of 100 die because the virus affects the muscles that help them breathe.

Rubella (German Measles) (Can be prevented by MMR vaccination)

Rubella is caused by a virus that is spread through coughing and sneezing. In children rubella usually causes a mild illness with fever, swollen glands, and a rash that lasts about 3 days. Rubella rarely causes serious illness or complications in children, but can be very serious to a baby in the womb. If a pregnant woman is infected, the result to the baby can be devastating, including miscarriage, serious heart defects, mental retardation and loss of hearing and eye sight.

Tetanus (Lockjaw) (Can be prevented by Tdap vaccination)

Tetanus mainly affects the neck and belly. When people are infected, the bacteria produce a toxin (poison) that causes muscles to become tight, which is very painful. This can lead to “locking” of the jaw so a person cannot open his or her mouth, swallow, or breathe. The bacteria that cause tetanus are found in soil, dust, and manure. The bacteria enter the body through a puncture, cut, or sore on the skin. Complete recovery from tetanus can take months. One to two out of 10 people who get tetanus die from the disease.

Varicella (Chickenpox) (Can be prevented by varicella vaccination)

Chickenpox is caused by the varicella zoster virus. Chickenpox is very contagious and spreads very easily from infected people. The virus can spread from either a cough, sneeze. It can also spread from the blisters on the skin, either by touching them or by breathing in these viral particles. Typical symptoms of chickenpox include an itchy rash with blisters, tiredness, headache and fever. Chickenpox is usually mild, but it can lead to severe skin infections, pneumonia, encephalitis (brain swelling), or even death.

Table 1. Vaccine-Preventable Diseases and the Vaccines that Prevent Them

| Disease | Vaccine | Disease spread by | Disease symptoms | Disease complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chickenpox | Varicella vaccine protects against chickenpox. | Air, direct contact | Rash, tiredness, headache, fever | Infected blisters, bleeding disorders, encephalitis (brain swelling), pneumonia (infection in the lungs) |

| Diphtheria | DTaP* vaccine protects against diphtheria. | Air, direct contact | Sore throat, mild fever, weakness, swollen glands in neck | Swelling of the heart muscle, heart failure, coma, paralysis, death |

| Haemophilus influenzae infections | Hib vaccine protects against Haemophilus influenzae type b. | Air, direct contact | May be no symptoms unless bacteria enter the blood | Meningitis (infection of the covering around the brain and spinal cord), intellectual disability, epiglottitis (life-threatening infection that can block the windpipe and lead to serious breathing problems), pneumonia (infection in the lungs), death |

| Hepatitis A | HepA vaccine protects against hepatitis A. | Direct contact, contaminated food or water | May be no symptoms, fever, stomach pain, loss of appetite, fatigue, vomiting, jaundice (yellowing of skin and eyes), dark urine | Liver failure, arthralgia (joint pain), kidney, pancreatic, and blood disorders |

| Hepatitis B | HepB vaccine protects against hepatitis B. | Contact with blood or body fluids | May be no symptoms, fever, headache, weakness, vomiting, jaundice (yellowing of skin and eyes), joint pain | Chronic liver infection, liver failure, liver cancer |

| Influenza (Flu) | Flu vaccine protects against influenza. | Air, direct contact | Fever, muscle pain, sore throat, cough, extreme fatigue | Pneumonia (infection in the lungs) |

| Measles | MMR** vaccine protects against measles. | Air, direct contact | Rash, fever, cough, runny nose, pinkeye | Encephalitis (brain swelling), pneumonia (infection in the lungs), death |

| Mumps | MMR**vaccine protects against mumps. | Air, direct contact | Swollen salivary glands (under the jaw), fever, headache, tiredness, muscle pain | Meningitis (infection of the covering around the brain and spinal cord) , encephalitis (brain swelling), inflam mation of testicles or ovaries, deafness |

| Pertussis | DTaP* vaccine protects against pertussis (whooping cough). | Air, direct contact | Severe cough, runny nose, apnea (a pause in breathing in infants) | Pneumonia (infection in the lungs), death |

| Polio | IPV vaccine protects against polio. | Air, direct contact, through the mouth | May be no symptoms, sore throat, fever, nausea, headache | Paralysis, death |

| Pneumococcal | PCV13 vaccine protects against pneumococcus. | Air, direct contact | May be no symptoms, pneumonia (infection in the lungs) | Bacteremia (blood infection), meningitis (infection of the covering around the brain and spinal cord), death |

| Rotavirus | RV vaccine protects against rotavirus. | Through the mouth | Diarrhea, fever, vomiting | Severe diarrhea, dehydration |

| Rubella | MMR** vaccine protects against rubella. | Air, direct contact | Children infected with rubella virus sometimes have a rash, fever, swollen lymph nodes | Very serious in pregnant women—can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, premature delivery, birth defects |

| Tetanus | DTaP* vaccine protects against tetanus. | Exposure through cuts in skin | Stiffness in neck and abdominal muscles, difficulty swallowing, muscle spasms, fever | Broken bones, breathing difficulty, death |

Footnotes: For Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Vaccine Recommendations and Guidelines go here: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs

* DTaP combines protection against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis.

** MMR combines protection against measles, mumps, and rubella.

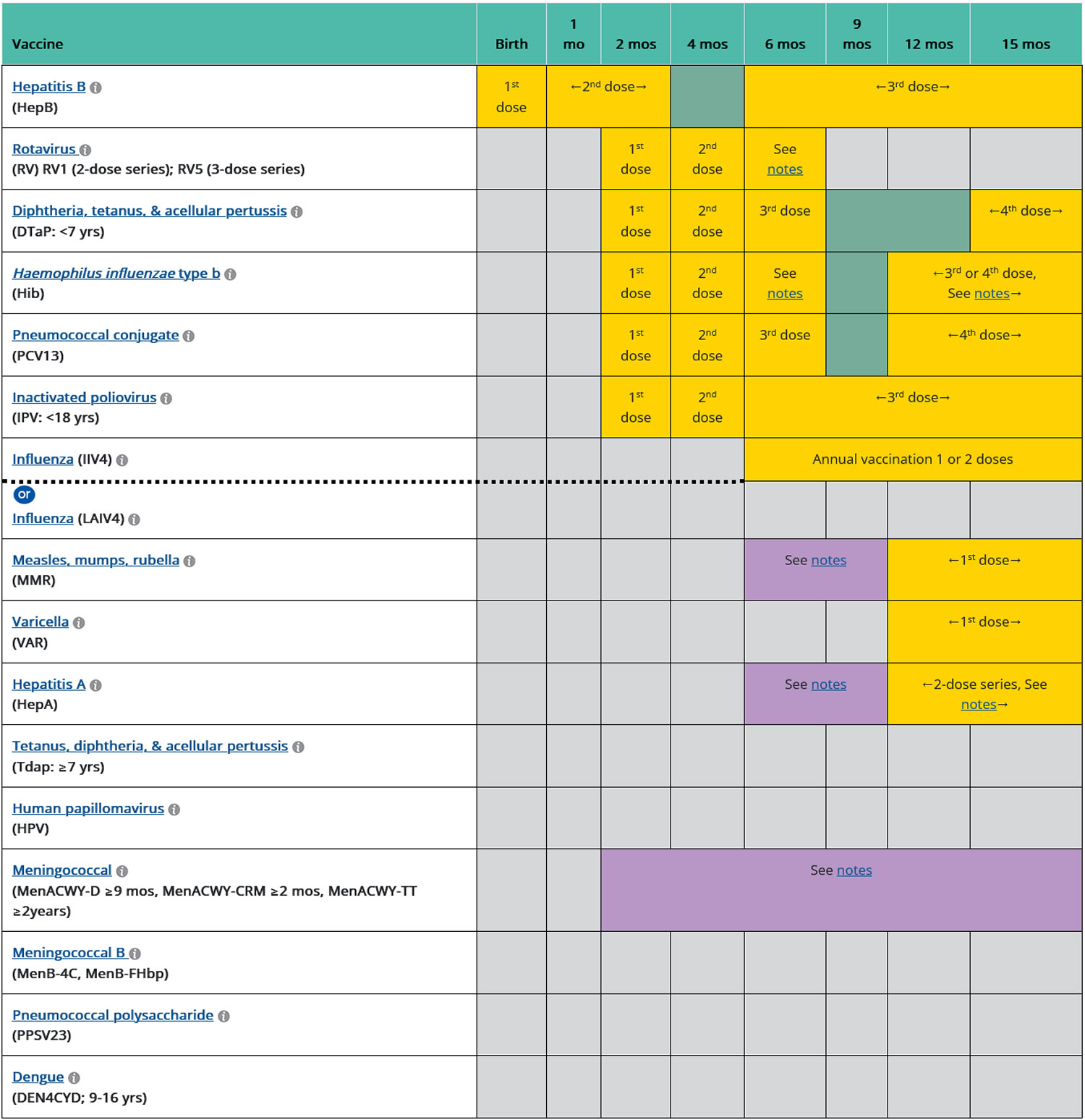

[Source 1 ]Table 2. Childhood vaccinations from birth to 15 months

Footnotes: YELLOW = Range of recommended ages for all children; GREEN = Range of recommended ages for catch-up immunization; PURPLE = Range of recommended ages for certain high-risk groups; BLUE = Recommended based on shared clinical decision-making or *can be used in this age group; GREY = No recommendation/Not applicable

- For calculating intervals between doses, 4 weeks = 28 days. Intervals of ≥4 months are determined by calendar months.

- Vaccine doses administered ≤4 days before the minimum age or interval are considered valid. Doses of any vaccine administered ≥5 days earlier than the minimum age or minimum interval should not be counted as valid and should be repeated as age-appropriate. The repeat dose should be spaced after the invalid dose by the recommended minimum interval.

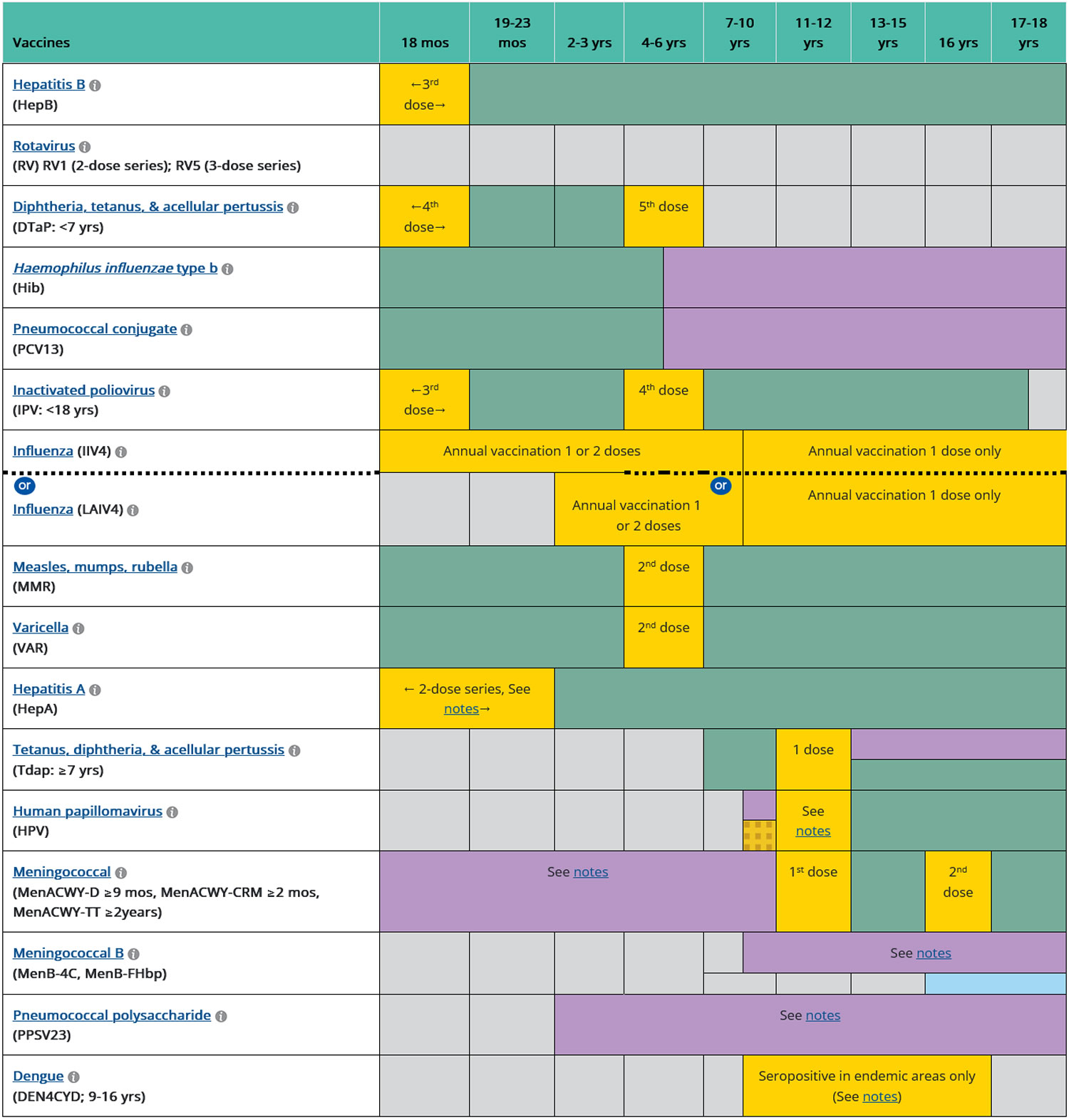

Table 3. Childhood vaccinations from 18 months to 18 years

Footnotes: YELLOW = Range of recommended ages for all children; GREEN = Range of recommended ages for catch-up immunization; PURPLE = Range of recommended ages for certain high-risk groups; BLUE = Recommended based on shared clinical decision-making or *can be used in this age group; GREY = No recommendation/Not applicable

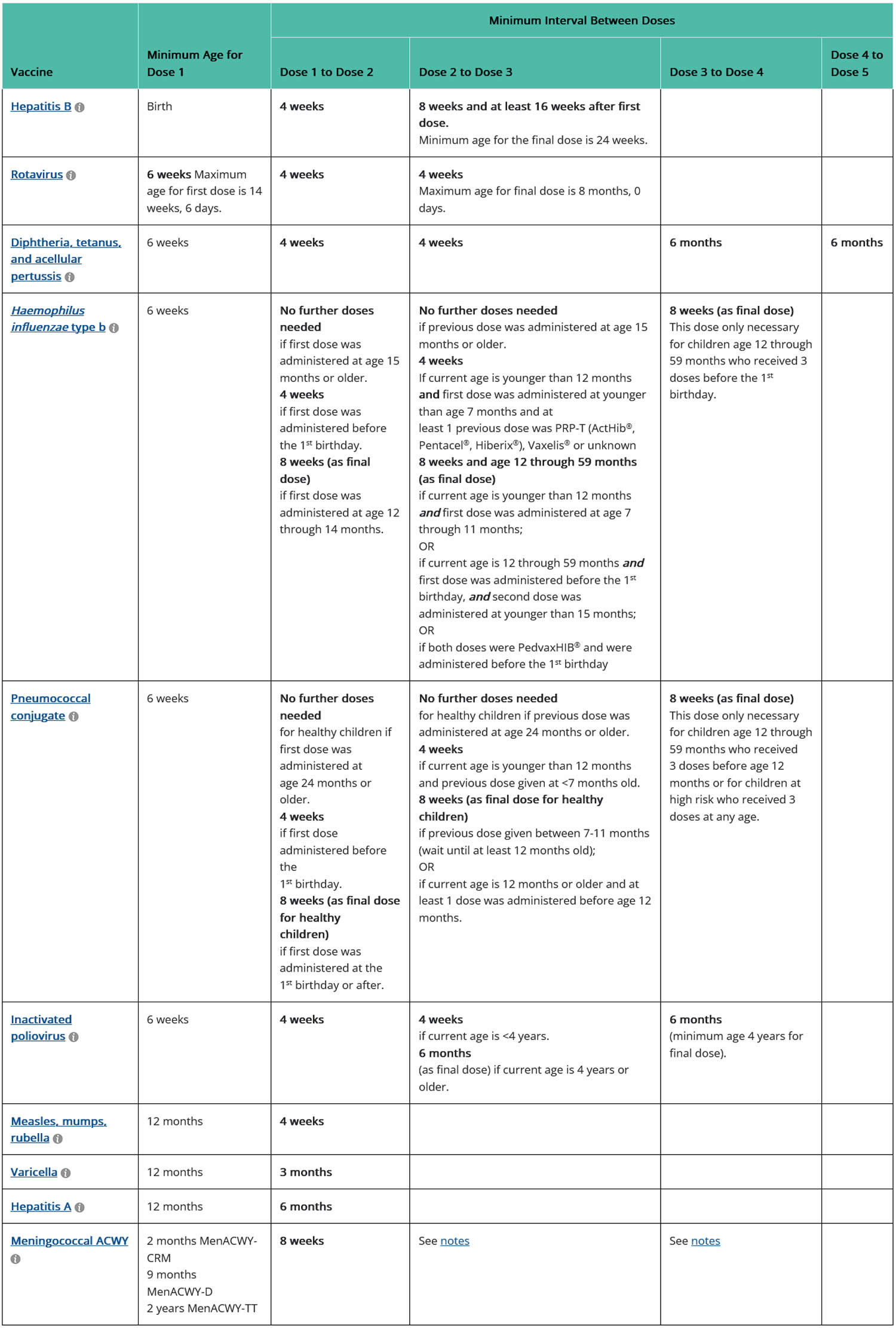

[Source 2 ]Table 4. Catch-up immunization schedule for children aged 4 months through 6 years who start late or who are more than 1 month behind, United States, 2022

Footnotes: Administer recommended vaccines if immunization history is incomplete or unknown. Do not restart or add doses to vaccine series for extended intervals between doses. When a vaccine is not administered at the recommended age, administer at a subsequent visit. The use of trade names is for identification purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices or CDC.

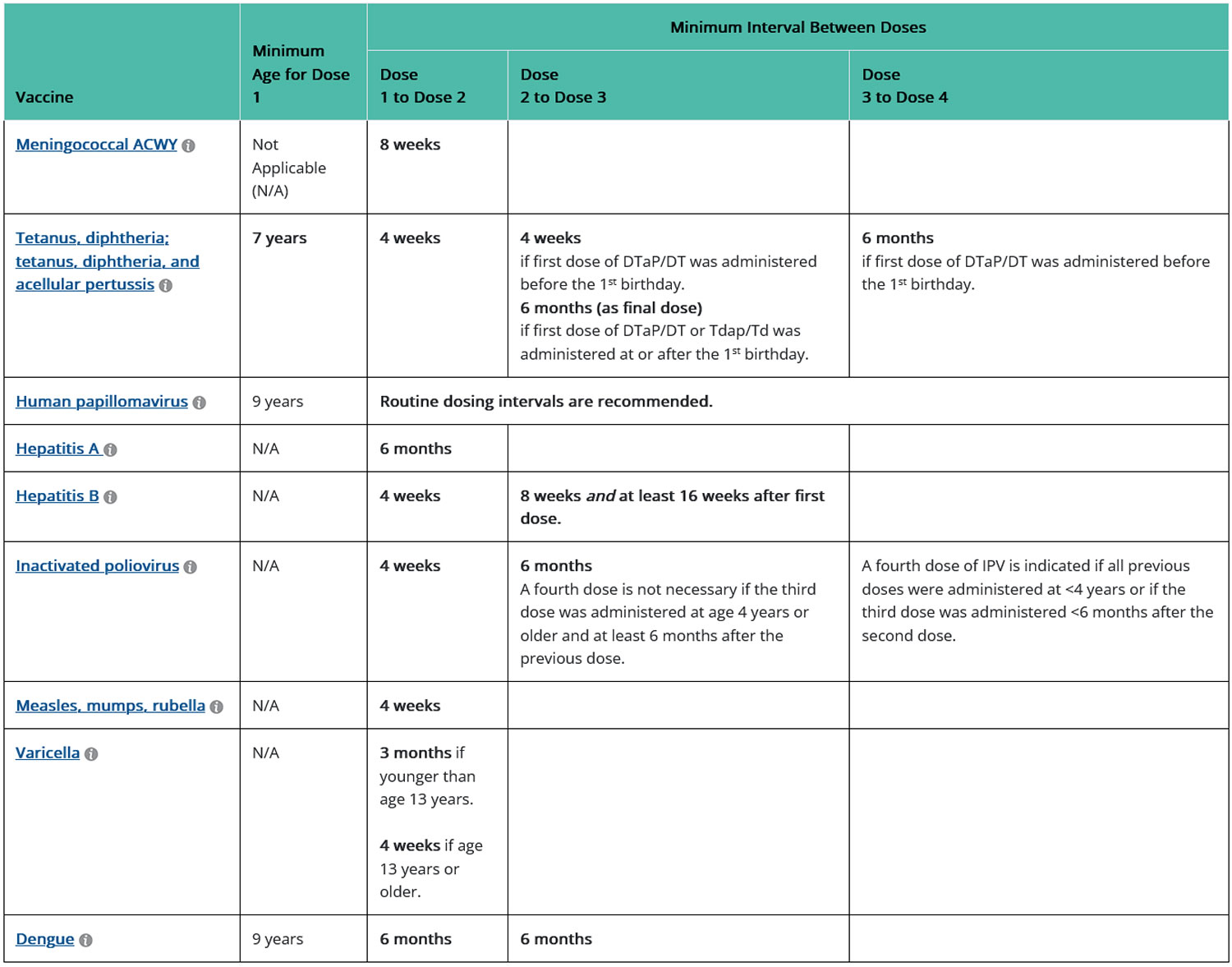

[Source 3 ]Table 5. Catch-up immunization schedule for children and adolescents age 7 through 18 years who start late or who are more than 1 month behind, United States, 2022

Footnotes: Administer recommended vaccines if immunization history is incomplete or unknown. Do not restart or add doses to vaccine series for extended intervals between doses. When a vaccine is not administered at the recommended age, administer at a subsequent visit. The use of trade names is for identification purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices or CDC.

[Source 3 ]Are vaccines safe?

Yes. Vaccines are very safe. The United States’ long-standing vaccine safety system ensures that vaccines are as safe as possible. Currently, the United States has the safest vaccine supply in its history. Millions of children safely receive vaccines each year. The most common side effects are typically very mild, such as pain or swelling at the injection site.

Childhood vaccinations list

List of Vaccines Used in United States 4:

- Adenovirus

- Anthrax

- AVA (BioThrax)

- Cholera

- Vaxchora

- Diphtheria

- DTaP (Daptacel, Infanrix)

- Td (Tenivac, generic)

- DT (-generic-)

- Tdap (Adacel, Boostrix)

- DTaP-IPV (Kinrix, Quadracel)

- DTaP-HepB-IPV (Pediarix)

- DTaP-IPV/Hib (Pentacel)

- Hepatitis A

- HepA (Havrix, Vaqta)

- HepA-HepB (Twinrix)

- Hepatitis B

- HepB (Engerix-B, Recombivax HB, Heplisav-B)

- DTaP-HepB-IPV (Pediarix)

- HepA-HepB (Twinrix)

- DTaP-IPV-Hib-HepB (Vaxelis)

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

- Hib (ActHIB, PedvaxHIB, Hiberix)

- DTaP-IPV/Hib (Pentacel)

- DTaP-IPV-Hib-HepB (Vaxelis)

- Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- HPV9 (Gardasil 9) (For scientific papers, the preferred abbreviation is 9vHPV)

- Seasonal Influenza (Flu) only

- IIV* (Afluria, Fluad, Flublok, Flucelvax, FluLaval, Fluarix, Fluvirin, Fluzone, Fluzone High-Dose, Fluzone Intradermal)

- *There are various acronyms for inactivated flu vaccines – IIV3, IIV4, RIV3, RIV4 and ccIIV4.

- LAIV (FluMist)

- Japanese Encephalitis

- JE (Ixiaro)

- Measles

- MMR (M-M-R II)

- MMRV (ProQuad)

- Meningococcal

- MenACWY (Menactra, Menveo)

- MenB (Bexsero, Trumenba)

- Mumps

- MMR (M-M-R II)

- MMRV (ProQuad)

- Pertussis

- DTaP (Daptacel, Infanrix)

- Tdap (Adacel, Boostrix)

- DTaP-IPV (Kinrix, Quadracel)

- DTaP-HepB-IPV (Pediarix)

- DTaP-IPV/Hib (Pentacel)

- Pneumococcal

- PCV13 (Prevnar13)

- PCV15 (Vaxneuvance)

- PCV20 (Prevnar20)

- PPSV23 (Pneumovax 23)

- Polio

- Polio (Ipol)

- DTaP-IPV (Kinrix, Quadracel)

- DTaP-HepB-IPV (Pediarix)

- DTaP-IPV/Hib (Pentacel)

- DTaP-IPV-Hib-HepB (Vaxelis)

- Rabies

- Rabies (Imovax Rabies, RabAvert)

- Rotavirus

- RV1 (Rotarix)

- RV5 (RotaTeq)

- Rubella

- MMR (M-M-R II)

- MMRV (ProQuad)

- Shingles

- RZV (Shingrix)

- Smallpox

- Vaccinia (ACAM2000):

- Tetanus

- DTaP (Daptacel, Infanrix)

- Td (Tenivac, generic)

- DT (-generic-)

- Tdap (Adacel, Boostrix)

- DTaP-IPV (Kinrix, Quadracel)

- DTaP-HepB-IPV (Pediarix)

- DTaP-IPV/Hib (Pentacel)

- DTaP-IPV-Hib-HepB (Vaxelis)

- Tuberculosis

- Typhoid Fever

- Typhoid Oral (Vivotif)

- Typhoid Polysaccharide (Typhim Vi)

- Varicella

- VAR (Varivax)

- MMRV (ProQuad):

- Yellow Fever

- YF (YF-Vax)

Table 6. Vaccines in the child and adolescent immunization schedule

| Vaccines | Abbreviations | Trade Names |

|---|---|---|

| Diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis vaccine | DTaP | Daptacel® Infanrix® |

| Diphtheria, tetanus vaccine | DT | No Trade Name |

| Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine | Hib (PRP-T) Hib (PRP-OMP) | ActHIB® Hiberix® PedvaxHIB® |

| Hepatitis A vaccine | HepA | Havrix® Vaqta® |

| Hepatitis B vaccine | HepB | Engerix-B® Recombivax HB® |

| Human papillomavirus vaccine | HPV | Gardasil 9® |

| Influenza vaccine (inactivated) | IIV | Multiple |

| Influenza vaccine (live, attenuated) | LAIV | FluMist® Quadrivalent |

| Measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine | MMR | M-M-R® II |

| Meningococcal serogroups A, C, W, Y vaccine | MenACWY-D MenACWY-CRM | Menactra® Menveo® |

| Meningococcal serogroup B vaccine | MenB-4C MenB-FHbp | Bexsero® Trumenba® |

| Pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine | PCV13 | Prevnar 13® |

| Pneumococcal 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine | PPSV23 | Pneumovax® 23 |

| Poliovirus vaccine (inactivated) | IPV | IPOL® |

| Rotavirus vaccine | RV1 RV5 | Rotarix® RotaTeq® |

| Tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine | Tdap | Adacel® Boostrix® |

| Tetanus and diphtheria vaccine | Td | Tenivac® TDvax™ |

| Varicella vaccine | VAR | Varivax® |

Table 7. Combination vaccines (use combination vaccines instead of separate injections when appropriate)

| Vaccines | Abbreviations | Trade Names |

|---|---|---|

| DTaP, hepatitis B, and inactivated poliovirus vaccine | DTaP-HepB-IPV | Pediarix® |

| DTaP, inactivated poliovirus, and Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine | DTaP-IPV/Hib | Pentacel® |

| DTaP and inactivated poliovirus vaccine | DTaP-IPV | Kinrix® Quadracel® |

| Measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccines | MMRV | ProQuad® |

List of childhood vaccines

Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP) vaccination

Minimum age: 6 weeks (4 years for Kinrix or Quadracel)

Routine vaccination

- 5-dose series at 2, 4, 6, 15–18 months, 4–6 years

- Prospectively: Dose 4 may be administered as early as age 12 months if at least 6 months have elapsed since dose 3.

- Retrospectively: A 4th dose that was inadvertently administered as early as 12 months may be counted if at least 4 months have elapsed since dose 3.

Catch-up vaccination

- Dose 5 is not necessary if dose 4 was administered at age 4 years or older and at least 6 months after dose 3.

- For other catch-up guidance, see Tables 4 and 5.

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccination

Minimum age: 6 weeks

Routine vaccination

- ActHIB, Hiberix, or Pentacel: 4-dose series at 2, 4, 6, 12–15 months

- PedvaxHIB: 3-dose series at 2, 4, 12–15 months

Catch-up vaccination

- Dose 1 at 7–11 months: Administer dose 2 at least 4 weeks later and dose 3 (final dose) at 12–15 months or 8 weeks after dose 2 (whichever is later).

- Dose 1 at 12–14 months: Administer dose 2 (final dose) at least 8 weeks after dose 1.

- Dose 1 before 12 months and dose 2 before 15 months: Administer dose 3 (final dose) 8 weeks after dose 2.

- 2 doses of PedvaxHIB before 12 months: Administer dose 3 (final dose) at 12–59 months and at least 8 weeks after dose 2.

- Unvaccinated at 15–59 months: 1 dose

- Previously unvaccinated children age 60 months or older who are not considered high risk do not require catch-up vaccination.

- For other catch-up guidance, see Table 4.

Special situations

- Chemotherapy or radiation treatment:

- 12–59 months

- Unvaccinated or only 1 dose before age 12 months: 2 doses, 8 weeks apart

- 2 or more doses before age 12 months: 1 dose at least 8 weeks after previous dose

- Doses administered within 14 days of starting therapy or during therapy should be repeated at least 3 months after therapy completion.

- 12–59 months

- Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT):

- 3-dose series 4 weeks apart starting 6 to 12 months after successful transplant regardless of Hib vaccination history

- Anatomic or functional asplenia (including sickle cell disease):

- 12–59 months

- Unvaccinated or only 1 dose before age 12 months: 2 doses, 8 weeks apart

- 2 or more doses before age 12 months: 1 dose at least 8 weeks after previous dose

- Unvaccinated* persons age 5 years or older

- 1 dose

- 12–59 months

- Elective splenectomy:

- Unvaccinated* persons age 15 months or older

- 1 dose (preferably at least 14 days before procedure)

- Unvaccinated* persons age 15 months or older

- HIV infection:

- 12–59 months

- Unvaccinated or only 1 dose before age 12 months: 2 doses, 8 weeks apart

- 2 or more doses before age 12 months: 1 dose at least 8 weeks after previous dose

- Unvaccinated* persons age 5–18 years

- 1 dose

- 12–59 months

- Immunoglobulin deficiency, early component complement deficiency:

- 12–59 months

- Unvaccinated or only 1 dose before age 12 months: 2 doses, 8 weeks apart

- 2 or more doses before age 12 months: 1 dose at least 8 weeks after previous dose

- 12–59 months

*Unvaccinated = Less than routine series (through 14 months) OR no doses (15 months or older)

Hepatitis A vaccination

Minimum age: 12 months for routine vaccination

Routine vaccination

- 2-dose series (minimum interval: 6 months) beginning at age

- 12 months

Catch-up vaccination

- Unvaccinated persons through 18 years should complete a 2-dose series (minimum interval: 6 months).

- Persons who previously received 1 dose at age 12 months or older should receive dose 2 at least 6 months after dose 1.

- Adolescents 18 years and older may receive the combined HepA and HepB vaccine, Twinrix®, as a 3-dose series (0, 1, and 6 months) or 4-dose series (0, 7, and 21–30 days, followed by a dose at 12 months).

International travel

- Persons traveling to or working in countries with high or intermediate endemic hepatitis A:

- Infants age 6–11 months: 1 dose before departure; revaccinate with 2 doses, separated by at least 6 months, between 12 and 23 months of age

- Unvaccinated age 12 months and older: Administer dose 1 as soon as travel is considered.

Hepatitis B vaccination

Minimum age: birth

Birth dose (monovalent HepB vaccine only)

- Mother is HBsAg-negative: 1 dose within 24 hours of birth for all medically stable infants ≥2,000 grams. Infants

- <2,000 grams: administer 1 dose at chronological age 1 month or hospital discharge.

- Mother is HBsAg-positive:

- Administer HepB vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) (in separate limbs) within 12 hours of birth, regardless of birth weight. For infants <2,000 grams, administer 3 additional doses of vaccine (total of 4 doses) beginning at age 1 month.

- Test for HBsAg and anti-HBs at age 9–12 months. If HepB series is delayed, test 1–2 months after final dose.

- Mother’s HBsAg status is unknown:

- Administer HepB vaccine within 12 hours of birth, regardless of birth weight.

- For infants <2,000 grams, administer HBIG in addition to HepB vaccine (in separate limbs) within 12 hours of birth. Administer 3 additional doses of vaccine (total of 4 doses) beginning at age 1 month.

- Determine mother’s HBsAg status as soon as possible. If mother is HBsAg-positive, administer HBIG to infants ≥2,000 grams as soon as possible, but no later than 7 days of age.

Routine series

- 3-dose series at 0, 1–2, 6–18 months (use monovalent HepB vaccine for doses administered before age 6 weeks)

- Infants who did not receive a birth dose should begin the series as soon as feasible (see Table 2).

- Administration of 4 doses is permitted when a combination vaccine containing HepB is used after the birth dose.

- Minimum age for the final (3rd or 4th ) dose: 24 weeks

- Minimum intervals: dose 1 to dose 2: 4 weeks / dose 2 to dose 3: 8 weeks / dose 1 to dose 3: 16 weeks (when 4 doses are administered, substitute “dose 4” for “dose 3” in these calculations)

Catch-up vaccination

- Unvaccinated persons should complete a 3-dose series at 0, 1–2, 6 months.

- Adolescents age 11–15 years may use an alternative 2-dose schedule with at least 4 months between doses (adult formulation Recombivax HB only).

- Adolescents 18 years and older may receive a 2-dose series of HepB (Heplisav-B®) at least 4 weeks apart.

- Adolescents 18 years and older may receive the combined HepA and HepB vaccine, Twinrix, as a 3-dose series (0, 1, and 6 months) or 4-dose series (0, 7, and 21–30 days, followed by a dose at 12 months).

- For other catch-up guidance, see see Table 4.

Special situations

- Revaccination is not generally recommended for persons with a normal immune status who were vaccinated as infants, children, adolescents, or adults.

- Revaccination may be recommended for certain populations, including:

- Infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers

- Hemodialysis patients

- Other immunocompromised persons

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination

Minimum age: 9 years

Routine and catch-up vaccination

- HPV vaccination routinely recommended at age 11–12 years (can start at age 9 years) and catch-up HPV vaccination recommended for all persons through age 18 years if not adequately vaccinated

- 2- or 3-dose series depending on age at initial vaccination:

- Age 9 through 14 years at initial vaccination: 2-dose series at 0, 6–12 months (minimum interval: 5 months; repeat dose if administered too soon)

- Age 15 years or older at initial vaccination: 3-dose series at 0, 1–2 months, 6 months (minimum intervals: dose 1 to dose 2: 4 weeks / dose 2 to dose 3: 12 weeks / dose 1 to dose 3: 5 months; repeat dose if administered too soon)

- If completed valid vaccination series with any HPV vaccine, no additional doses needed

Special situations

- Immunocompromising conditions, including HIV infection: 3-dose series as above

- History of sexual abuse or assault: Start at age 9 years

- Pregnancy: HPV vaccination not recommended until after pregnancy; no intervention needed if vaccinated while pregnant; pregnancy testing not needed before vaccination

Influenza vaccination

Minimum age: 6 months [IIV], 2 years [LAIV], 18 years [recombinant influenza vaccine, RIV]

Routine vaccination

- Use any influenza vaccine appropriate for age and health status annually:

- 2 doses, separated by at least 4 weeks, for children age 6 months–8 years who have received fewer than 2 influenza vaccine doses before July 1, 2019, or whose influenza vaccination history is unknown (administer dose 2 even if the child turns 9 between receipt of dose 1 and dose 2)

- 1 dose for children age 6 months–8 years who have received at least 2 influenza vaccine doses before July 1, 2019

- 1 dose for all persons age 9 years and older

- For the 2020–21 season, see the 2020–21 Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices influenza vaccine recommendations.

Special situations

- Egg allergy, hives only: Any influenza vaccine appropriate for age and health status annually

- Egg allergy with symptoms other than hives (e.g., angioedema, respiratory distress, need for emergency medical services or epinephrine): Any influenza vaccine appropriate for age and health status annually in medical setting under supervision of health care provider who can recognize and manage severe allergic reactions

- LAIV should not be used in persons with the following conditions or situations:

- History of severe allergic reaction to a previous dose of any influenza vaccine or to any vaccine component (excluding egg, see details above)

- Receiving aspirin or salicylate-containing medications

- Age 2–4 years with history of asthma or wheezing

- Immunocompromised due to any cause (including medications and HIV infection)

- Anatomic or functional asplenia

- Cochlear implant

- Cerebrospinal fluid-oropharyngeal communication

- Close contacts or caregivers of severely immunosuppressed persons who require a protected environment

- Pregnancy

- Received influenza antiviral medications within the previous 48 hours

Measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination

Minimum age: 12 months for routine vaccination

Routine vaccination

- 2-dose series at 12–15 months, 4–6 years

- Dose 2 may be administered as early as 4 weeks after dose 1.

Catch-up vaccination

- Unvaccinated children and adolescents: 2-dose series at least 4 weeks apart

- The maximum age for use of MMRV is 12 years.

Special situations

- International travel

- Infants age 6–11 months: 1 dose before departure; revaccinate with 2-dose series with dose 1 at 12–15 months (12 months for children in high-risk areas) and dose 2 as early as 4 weeks later.

- Unvaccinated children age 12 months and older: 2-dose series at least 4 weeks apart before departure

Meningococcal serogroup A,C,W,Y vaccination

Minimum age: 2 months [MenACWY-CRM, Menveo], 9 months [MenACWY-D, Menactra]

Routine vaccination

- 2-dose series at 11–12 years, 16 years

Catch-up vaccination

- Age 13–15 years: 1 dose now and booster at age 16–18 years (minimum interval: 8 weeks)

- Age 16–18 years: 1 dose

Special situations

- Anatomic or functional asplenia (including sickle cell disease), HIV infection, persistent complement component deficiency, complement inhibitor (e.g., eculizumab, ravulizumab) use:

- Menveo

- Dose 1 at age 8 weeks: 4-dose series at 2, 4, 6, 12 months

- Dose 1 at age 7–23 months: 2-dose series (dose 2 at least 12 weeks after dose 1 and after age 12 months)

- Dose 1 at age 24 months or older: 2-dose series at least 8 weeks apart

- Menactra

- Persistent complement component deficiency or complement inhibitor use:

- Age 9–23 months: 2-dose series at least 12 weeks apart

- Age 24 months or older: 2-dose series at least 8 weeks apart

- Anatomic or functional asplenia, sickle cell disease, or HIV infection:

- Age 9–23 months: Not recommended

- Age 24 months or older: 2-dose series at least 8 weeks apart

- Menactra must be administered at least 4 weeks after completion of PCV13 series.

- Persistent complement component deficiency or complement inhibitor use:

- Menveo

- Travel in countries with hyperendemic or epidemic meningococcal disease, including countries in the African meningitis belt or during the Hajj:

- Children less than age 24 months:

- Menveo (age 2–23 months):

- Dose 1 at 8 weeks: 4-dose series at 2, 4, 6, 12 months

- Dose 1 at 7–23 months: 2-dose series (dose 2 at least 12 weeks after dose 1 and after age 12 months)

- Menactra (age 9–23 months):

- 2-dose series (dose 2 at least 12 weeks after dose 1; dose 2 may be administered as early as 8 weeks after dose 1 in travelers)

- Menveo (age 2–23 months):

- Children age 2 years or older: 1 dose Menveo or Menactra

- Children less than age 24 months:

- First-year college students who live in residential housing (if not previously vaccinated at age 16 years or older) or military recruits:

- 1 dose Menveo or Menactra

- Adolescent vaccination of children who received MenACWY prior to age 10 years:

- Children for whom boosters are recommended because of an ongoing increased risk of meningococcal disease (e.g., those with complement deficiency, HIV, or asplenia): Follow the booster schedule for persons at increased risk (see below).

- Children for whom boosters are not recommended (e.g., those who received a single dose for travel to a country where meningococcal disease is endemic): Administer MenACWY according to the recommended adolescent schedule with dose 1 at age 11–12 years and dose 2 at age 16 years.

Note: Menactra should be administered either before or at the same time as DTaP. For MenACWY booster dose recommendations for groups listed under “Special situations” and in an outbreak setting.

Meningococcal serogroup B vaccination

Minimum age: 10 years [MenB-4C, Bexsero; MenB-FHbp, Trumenba]

Shared clinical decision-making

- Adolescents not at increased risk age 16–23 years (preferred age 16–18 years) based on shared clinical decision-making:

- Bexsero: 2-dose series at least 1 month apart

- Trumenba: 2-dose series at least 6 months apart; if dose 2 is administered earlier than 6 months, administer a 3rd dose at least 4 months after dose 2.

Special situations

- Anatomic or functional asplenia (including sickle cell disease), persistent complement component deficiency, complement inhibitor (e.g., eculizumab, ravulizumab) use:

- Bexsero: 2-dose series at least 1 month apart

- Trumenba: 3-dose series at 0, 1–2, 6 months

Bexsero and Trumenba are not interchangeable; the same product should be used for all doses in a series.

Pneumococcal vaccination

Minimum age: 6 weeks [PCV13], 2 years [PPSV23]

Routine vaccination with PCV13

- 4-dose series at 2, 4, 6, 12–15 months

Catch-up vaccination with PCV13

- 1 dose for healthy children age 24–59 months with any incomplete* PCV13 series

- For other catch-up guidance, see Tables 4 and 5.

Special situations

- High-risk conditions below: When both PCV13 and PPSV23 are indicated, administer PCV13 first. PCV13 and PPSV23 should not be administered during the same visit.

- Chronic heart disease (particularly cyanotic congenital heart disease and cardiac failure), chronic lung disease (including asthma treated with high-dose, oral corticosteroids), diabetes mellitus:

- Age 2–5 years

- Any incomplete* series with:

- 3 PCV13 doses: 1 dose PCV13 (at least 8 weeks after any prior PCV13 dose)

- Less than 3 PCV13 doses: 2 doses PCV13 (8 weeks after the most recent dose and administered 8 weeks apart)

- No history of PPSV23: 1 dose PPSV23 (at least 8 weeks after any prior PCV13 dose)

- Any incomplete* series with:

- Age 6–18 years

- No history of PPSV23: 1 dose PPSV23 (at least 8 weeks after any prior PCV13 dose)

- Age 2–5 years

- Cerebrospinal fluid leak, cochlear implant:

- Age 2–5 years

- Any incomplete* series with:

- 3 PCV13 doses: 1 dose PCV13 (at least 8 weeks after any prior PCV13 dose)

- Less than 3 PCV13 doses: 2 doses PCV13 (8 weeks after the most recent dose and administered 8 weeks apart)

- No history of PPSV23: 1 dose PPSV23 (at least 8 weeks after any prior PCV13 dose)

- Any incomplete* series with:

- Age 6–18 years

- No history of either PCV13 or PPSV23: 1 dose PCV13, 1 dose PPSV23 at least 8 weeks later

- Any PCV13 but no PPSV23: 1 dose PPSV23 at least 8 weeks after the most recent dose of PCV13

- PPSV23 but no PCV13: 1 dose PCV13 at least 8 weeks after the most recent dose of PPSV23

- Age 2–5 years

- Sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies; anatomic or functional asplenia; congenital or acquired immunodeficiency; HIV infection; chronic renal failure; nephrotic syndrome; malignant neoplasms, leukemias, lymphomas, Hodgkin disease, and other diseases associated with treatment with immunosuppressive drugs or radiation therapy; solid organ transplantation; multiple myeloma:

- Age 2–5 years

- Any incomplete* series with:

- 3 PCV13 doses: 1 dose PCV13 (at least 8 weeks after any prior PCV13 dose)

- Less than 3 PCV13 doses: 2 doses PCV13 (8 weeks after the most recent dose and administered 8 weeks apart)

- No history of PPSV23: 1 dose PPSV23 (at least 8 weeks after any prior PCV13 dose) and a 2nd dose of PPSV23 5 years later

- Any incomplete* series with:

- Age 6–18 years

- No history of either PCV13 or PPSV23: 1 dose PCV13, 2 doses PPSV23 (dose 1 of PPSV23 administered 8 weeks after PCV13 and dose 2 of PPSV23 administered at least 5 years after dose 1 of PPSV23)

- Any PCV13 but no PPSV23: 2 doses PPSV23 (dose 1 of PPSV23 administered 8 weeks after the most recent dose of PCV13 and dose 2 of PPSV23 administered at least 5 years after dose 1 of PPSV23)

- PPSV23 but no PCV13: 1 dose PCV13 at least 8 weeks after the most recent PPSV23 dose and a 2nd dose of PPSV23 administered 5 years after dose 1 of PPSV23 and at least 8 weeks after a dose of PCV13

- Age 2–5 years

- Chronic liver disease, alcoholism:

- Age 6–18 years

- No history of PPSV23: 1 dose PPSV23 (at least 8 weeks after any prior PCV13 dose)

- Age 6–18 years

*Incomplete series = Not having received all doses in either the recommended series or an age-appropriate catch-up series.

Poliovirus vaccination

Minimum age: 6 weeks

Routine vaccination

- 4-dose series at ages 2, 4, 6–18 months, 4–6 years; administer the final dose at or after age 4 years and at least 6 months after the previous dose.

- 4 or more doses of IPV can be administered before age 4 years when a combination vaccine containing IPV is used. However, a dose is still recommended at or after age 4 years and at least 6 months after the previous dose.

Catch-up vaccination

- In the first 6 months of life, use minimum ages and intervals only for travel to a polio-endemic region or during an outbreak.

- IPV is not routinely recommended for U.S. residents 18 years and older.

Series containing oral polio vaccine (OPV), either mixed OPV-IPV or OPV-only series:

- Total number of doses needed to complete the series is the same as that recommended for the U.S. IPV schedule.

- Only trivalent OPV (tOPV) counts toward the U.S. vaccination requirements.

- Doses of OPV administered before April 1, 2016, should be counted (unless specifically noted as administered during a campaign).

- Doses of OPV administered on or after April 1, 2016, should not be counted.

- For other catch-up guidance, see Tables 4 and 5.

Rotavirus vaccination

Minimum age: 6 weeks

Routine vaccination

- Rotarix: 2-dose series at 2 and 4 months

- RotaTeq: 3-dose series at 2, 4, and 6 months

- If any dose in the series is either RotaTeq or unknown, default to 3-dose series.

Catch-up vaccination

- Do not start the series on or after age 15 weeks, 0 days.

- The maximum age for the final dose is 8 months, 0 days.

- For other catch-up guidance, see Tables 4 and 5.

Tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination

Minimum age: 11 years for routine vaccination, 7 years for catch-up vaccination

Routine vaccination

- Adolescents age 11–12 years: 1 dose Tdap

- Pregnancy: 1 dose Tdap during each pregnancy, preferably in early part of gestational weeks 27–36

- Tdap may be administered regardless of the interval since the last tetanus- and diphtheria-toxoid-containing vaccine.

Catch-up vaccination

- Adolescents age 13–18 years who have not received Tdap: 1 dose Tdap, then Td or Tdap booster every 10 years

- Persons age 7–18 years not fully vaccinated* with DTaP: 1 dose Tdap as part of the catch-up series (preferably the first dose); if additional doses are needed, use Td or Tdap.

- Tdap administered at 7–10 years

- Children age 7–9 years who receive Tdap should receive the routine Tdap dose at age 11–12 years.

- Children age 10 years who receive Tdap do not need to receive the routine Tdap dose at age 11–12 years.

- DTaP inadvertently administered at or after age 7 years:

- Children age 7–9 years: DTaP may count as part of catch-up series. Routine Tdap dose at age 11–12 years should be administered.

- Children age 10–18 years: Count dose of DTaP as the adolescent Tdap booster.

- For other catch-up guidance, see Tables 4 and 5.

*Fully vaccinated = 5 valid doses of DTaP OR 4 valid doses of DTaP if dose 4 was administered at age 4 years or older.

Varicella vaccination

Minimum age: 12 months

Routine vaccination

- 2-dose series at 12–15 months, 4–6 years

- Dose 2 may be administered as early as 3 months after dose 1 (a dose administered after a 4-week interval may be counted).

Catch-up vaccination

- Ensure persons age 7–18 years without evidence of immunity have 2-dose series:

- Age 7–12 years: routine interval: 3 months (a dose administered after a 4-week interval may be counted)

- Age 13 years and older: routine interval: 4–8 weeks (minimum interval: 4 weeks)

- The maximum age for use of MMRV is 12 years.

Vaccine ingredients sorted by vaccine

Vaccines contain ingredients, called antigens, which cause the body to develop immunity. Vaccines also contain very small amounts of other ingredients. All ingredients either help make the vaccine, or ensure the vaccine is safe and effective. These types of ingredients are listed below.

Table 8. Vaccine ingredients

| Type of Ingredient | Examples | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Preservatives | Thimerosal (only in multi-dose vials of flu vaccine)* | To prevent contamination |

| Adjuvants | Aluminum salts | To help stimulate the body’s response to the antigens |

| Stabilizers | Sugars, gelatin | To keep the vaccine potent during transportation and storage |

| Residual cell culture materials | Egg protein | To grow enough of the virus or bacteria to make the vaccine |

| Residual inactivating ingredients | Formaldehyde | To kill viruses or inactivate toxins during the manufacturing process |

| Residual antibiotics | Neomycin | To prevent contamination by bacteria during the vaccine manufacturing process |

Footnote: *Today, the only childhood vaccines used routinely in the United States that contain thimerosal (mercury) are flu vaccines in multi-dose vials. These vials have very tiny amounts of thimerosal as a preservative. This is necessary because each time an individual dose is drawn from a multi-dose vial with a new needle and syringe, there is the potential to contaminate the vial with harmful microbes (toxins).

[Source 6 ]Additional Facts

Additives used in the production of vaccines may include:

- suspending fluid (e.g. sterile water, saline, or fluids containing protein);

- preservatives and stabilizers to help the vaccine remain unchanged (e.g. albumin, phenols, and glycine); and

- adjuvants or enhancers to help the vaccine to be more effective.

Common substances found in vaccines include 6:

- Aluminum gels or salts of aluminum which are added as adjuvants to help the vaccine stimulate a better response. Adjuvants help promote an earlier, more potent response, and more persistent immune response to the vaccine.

- Antibiotics which are added to some vaccines to prevent the growth of germs (bacteria) during production and storage of the vaccine. No vaccine produced in the United States contains penicillin.

- Egg protein is found in influenza and yellow fever vaccines, which are prepared using chicken eggs. Ordinarily, persons who are able to eat eggs or egg products safely can receive these vaccines.

- Formaldehyde is used to inactivate bacterial products for toxoid vaccines, (these are vaccines that use an inactive bacterial toxin to produce immunity.) It is also used to kill unwanted viruses and bacteria that might contaminate the vaccine during production. Most formaldehyde is removed from the vaccine before it is packaged.

- Monosodium glutamate (MSG) and 2-phenoxy-ethanol which are used as stabilizers in a few vaccines to help the vaccine remain unchanged when the vaccine is exposed to heat, light, acidity, or humidity.

- Thimerosal is a mercury-containing preservative that is added to vials of vaccine that contain more than one dose to prevent contamination and growth of potentially harmful bacteria.

For children with a prior history of allergic reactions to any of these substances in vaccines, parents should consult their child’s healthcare provider before vaccination.

Thimerosal, Mercury, and Vaccine Safety

Thimerosal is a compound that contains mercury 7. Mercury is a metal found naturally in the environment. Thimerosal is used as a preservative in multi-dose vials of flu vaccines, and in two other childhood vaccines, it is used in the manufacturing process. When each new needle is inserted into the multi-dose vial, it is possible for microbes to get into the vial. The preservative, thimerosal, prevents contamination in the multi-dose vial when individual doses are drawn from it. Receiving a vaccine contaminated with bacteria can be deadly.

There is no evidence that the small amounts of thimerosal in flu vaccines cause any harm, except for minor reactions like redness and swelling at the injection site. Although no evidence suggests that there are safety concerns with thimerosal, vaccine manufacturers have stopped using it as a precautionary measure. Flu vaccines that do not contain thimerosal are available (in single dose vials).

Today, no childhood vaccine used in the U.S.—except some formulations of flu vaccine in multi-dose vials—use thimerosal as a preservative.

Was thimerosal in vaccines a cause of autism?

Reputable scientific studies have shown that mercury in vaccines given to young children is not a cause of autism. The studies used different methods. Some examined rates of autism in a state or a country, comparing autism rates before and after thimerosal was removed as a preservative from vaccines. In the United States and other countries, the number of children diagnosed with autism has not gone down since thimerosal was removed from vaccines.

What keeps today’s childhood vaccines from becoming contaminated if they do not contain thimerosal as a preservative?

The childhood vaccines that used to contain thimerosal as a preservative are now put into single-dose vials, so no preservative is needed. In the past, the vaccines were put into multi-dose vials, which could become contaminated when new needles were used to get vaccine out of the vial for each dose.

Vaccine side effects and risks

Like any medication, vaccines can cause side effects. The most common side effects are mild. On the other hand, many vaccine-preventable disease symptoms can be serious, or even deadly. Even though many of these diseases are rare in this country, they still occur around the world. Unvaccinated U.S. citizens who travel abroad can bring these diseases to the U.S., putting unvaccinated children at risk.

The side effects from vaccines are almost always minor (such as redness and swelling where the shot was given) and go away within a few days. If your child experiences a reaction at the injection site, use a cool, wet cloth to reduce redness, soreness, and swelling.

Serious side effects after vaccination, such as severe allergic reaction, are very rare and doctors and clinic staff are trained to deal with them. Pay extra attention to your child for a few days after vaccination. If you see something that concerns you, call your child’s doctor.

Immunization vs Vaccination

The terms ‘vaccination’ and ‘immunization’ don’t mean quite the same thing. Vaccination is the term used for getting a vaccine, that is, actually getting the injection or taking an oral vaccine dose. Immunization refers to the process of both getting the vaccine and becoming immune to the disease following vaccination. Vaccines train your immune system to quickly recognize and clear out germs (bacteria and viruses) that can cause serious illnesses. Vaccines strengthen your immune system a bit like exercise strengthens muscles.

How does immunization work?

All forms of immunization work in the same way. When someone is injected with a vaccine, their body produces an immune response in the same way it would following exposure to a disease but without the person getting the disease. If the person comes in contact with the disease in the future, the body is able to make an immune response fast enough to prevent the person developing the disease or developing a severe case of the disease.

Vaccines are a safe and clever way of producing an immune response in the body without causing illness.

Vaccines use dead or severely weakened viruses to trick your body into thinking you have already had the disease.

When you get a vaccine, your immune system responds to these weakened ‘invaders’ and creates antibodies to protect you against future infection. It has special ‘memory’ cells that remember and recognize specific germs or viruses.

Vaccines strengthen your immune system by training it to recognize and fight against specific germs.

When you come across that virus in the future, your immune system rapidly produces antibodies to destroy it. In some cases, you may still get a less serious form of the illness, but you are protected from the most dangerous effects.

How does the immune system works?

Every day you come into contact with germs, including bacteria and viruses. A healthy immune system stops you getting sick from these germs.

The immune response is the way your body defends itself. It recognizes harmful bacteria, viruses and any other substances, also known as antigens, when they enter your body.

When an antigen like the cold virus enters your body, your immune response first produces something called mucus. The mucus tries to flush out the virus and stop more of it from entering the body.

Next, your immune response can send white blood cells to surround the virus to prevent more harm.

Lastly, it can produce special cells called antibodies. Antibodies can lock onto and destroy the virus.

The immune system is at work all the time to keep you as healthy as possible.

How Vaccines Prevent Diseases

The diseases vaccines prevent can be dangerous, or even deadly. Vaccines reduce your or your child’s risk of infection by working with your or your child body’s natural defenses to help them safely develop immunity to disease.

When germs, such as bacteria or viruses, invade the body, they attack and multiply. This invasion is called an infection, and the infection is what causes illness. The immune system then has to fight the infection. Once it fights off the infection, the body has a supply of cells that help recognize and fight that disease in the future. These supplies of cells are called antibodies.

Vaccines help develop immunity by imitating an infection, but this “imitation” infection does not cause illness. Instead it causes the immune system to develop the same response as it does to a real infection so the body can recognize and fight the vaccine-preventable disease in the future. Sometimes, after getting a vaccine, the imitation infection can cause minor symptoms, such as fever. Such minor symptoms are normal and should be expected as the body builds immunity.

As children get older, they require additional doses of some vaccines for best protection. Older kids also need protection against additional diseases they may encounter.

What if we stopped vaccinating?

So what would happen if we stopped vaccinating here? Diseases that are almost unknown would stage a comeback. Before long you would see epidemics of diseases that are nearly under control today. More children would get sick and more would die.

In 1974, Japan had a successful pertussis (whooping cough) vaccination program, with nearly 80% of Japanese children vaccinated. That year only 393 cases of pertussis were reported in the entire country, and there were no deaths from pertussis. But then rumors began to spread that pertussis vaccination was no longer needed and that the vaccine was not safe, and by 1976 only 10% of infants were getting vaccinated. In 1979 Japan suffered a major pertussis epidemic, with more than 13,000 cases of whooping cough and 41 deaths. In 1981 the government began vaccinating with acellular pertussis vaccine, and the number of pertussis cases dropped again.

Why get immunization?

As a parent, you may get upset or concerned when you watch your baby get 3 or 4 shots during a doctor’s visit. But, all of those shots add up to protection for your baby against 14 infectious diseases. Young babies can get very ill from vaccine-preventable diseases.

Immunization is a safe and effective way to protect you and your children from harmful, contagious diseases. Immunization also safeguards the health of other people, now and for future generations.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices 8, a group of medical and public health experts that develops recommendations on how to use vaccines to control diseases in the United States, designs the vaccination schedule. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices 8 designs the vaccination schedule to protect young children before they are likely to be exposed to potentially serious diseases and when they are most vulnerable to serious infections.

Although children continue to get several vaccines up to their second birthday, these vaccines do not overload the immune system. Every day, your healthy baby’s immune system successfully fights off thousands of antigens – the parts of germs that cause their immune system to respond. The antigens in vaccines come from weakened or killed germs so they cannot cause serious illness. Even if your child receives several vaccines in one day, vaccines contain only a tiny amount of antigens compared to the antigens your baby encounters every day.

This is the case even if your child receives combination vaccines. Combination vaccines take two or more vaccines that could be given individually and put them into one shot. Children get the same protection as they do from individual vaccines given separately—but with fewer shots.

Before vaccination campaigns in the 1960s and 1970s, diseases like tetanus, diphtheria, and whooping cough killed thousands of children. Today, it is extremely rare to die from these diseases in America.

When you get immunized, you protect yourself as well as helping to protect the whole community. When enough people in the community get immunized, it is more difficult for these diseases to spread. This helps to protect people who are at more risk of getting the disease, including unvaccinated members of the community. This means that even those who are too young or too sick to be vaccinated will not encounter the disease. Scientists call this ‘herd immunity’ and it can save lives.

If enough people in the community get immunized against a disease, the infection can no longer spread from person to person. The disease can die out altogether. For example, smallpox was eradicated in 1980 after a vaccination campaign led by the World Health Organization.

A similar campaign by the Global Polio Eradication Initiative has succeeded in reducing the number of polio cases. There are now only a few cases remaining in the developing world today.

Is ‘natural’ immunization better?

If a disease infects you, then you may become immune to it in the future. Doctors call this ‘natural’ immunity.

Some people believe that natural immunity is better than the immunity from vaccines. But the risks associated with natural immunity are much higher than risks associated with immunity provided by vaccines. Some highly contagious diseases can lead to severe complications. They can make you very ill or even kill you.

The benefits of vaccination far outweigh the risks. Vaccination protects you and your family from diseases, including ones that are deadly. It also protects other people in your community, including people who are vulnerable, too young, or too sick to be immunized.

The estimation is that immunization programs prevent about 2.5 million deaths every year.

Vaccination also helps protect the health of future generations, for example against the crippling disease polio.

Isn’t it better for children to develop immunity from the disease?

Allowing children to develop immunity by catching the diseases is not safe. Although catching a vaccine-preventable disease often protects a child from catching it again, it can make them seriously ill in the process. In comparison, vaccines are designed so that they can stimulate immunity but without causing disease. The side e ffects of vaccination are usually mild (like getting a sore arm) and pass quickly but the diseases they prevent can cause serious illnesses requiring hospital treatment. Occasionally children still die in United States from vaccine-preventable diseases. Vaccination is recommended because it is the safest way to develop immunity.

What are the risks and benefits of vaccines?

Vaccines can prevent infectious diseases that once killed or harmed many infants, children, and adults. Without vaccines, your child is at risk for getting seriously ill and suffering pain, disability, and even death from diseases like measles and whooping cough. The main risks associated with getting vaccines are side effects, which are almost always mild (redness and swelling at the injection site) and go away within a few days. Serious side effects after vaccination, such as a severe allergic reaction, are very rare and doctors and clinic staff are trained to deal with them. The disease-prevention benefits of getting vaccines are much greater than the possible side effects for almost all children. The only exceptions to this are cases in which a child has a serious chronic medical condition like cancer or a disease that weakens the immune system, or has had a severe allergic reaction to a previous vaccine dose.

How long do immunizations take to work?

In general, the normal immune response takes approximately 2 weeks to work. This means protection from an infection will not occur immediately after immunization. Most immunizations need to be given several times to build long-lasting protection.

A child who has been given only one or two doses of diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine (DTPa) is only partially protected against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (whooping cough), and may become sick if exposed to these diseases. However, some of the new vaccines, such as the meningococcal C vaccine, provide long-lasting immunity after only one dose.

How long do immunizations last?

The protective effect of immunizations is not always lifelong. Some, like tetanus vaccine, can last up to 30 years, after which time a booster dose may be given. Some immunizations, such as whooping cough vaccine, give protection for about 5 years after a full course. Influenza immunization is needed annually due to frequent changes to the type of flu virus in the community.

Is everyone protected from disease by immunization?

Even when all the doses of a vaccine have been given, not everyone is protected against the disease. Measles, mumps, rubella, tetanus, polio, hepatitis B and Hib vaccines protect more than 95% of children who have completed the course. One dose of meningococcal C vaccine at 12 months protects over 90% of children.

Three doses of whooping cough vaccine protects about 85% of children who have been immunized, and will reduce the severity of the disease in the other 15%, if they do catch whooping cough. Booster doses are needed because immunity decreases over time.

What is in vaccines?

Some vaccines contain a very small dose of a live, but weakened form of a virus. Some vaccines contain a very small dose of killed bacteria or small parts of bacteria, and other vaccines contain a small dose of a modified toxin produced by bacteria.

Vaccines may also contain either a small amount of preservative or a small amount of an antibiotic to preserve the vaccine. Some vaccines may also contain a small amount of an aluminium salt which helps produce a better immune response.

Is there a link between vaccines and autism?

No. Scientific studies and reviews continue to show no relationship between vaccines and autism.

Some people have suggested that thimerosal (a compound that contains mercury) in vaccines given to infants and young children might be a cause of autism. Others have suggested that the MMR (measles- mumps-rubella) vaccine may be linked to autism. However, numerous scientists and researchers have studied and continue to study the MMR vaccine and thimerosal, and reach the same conclusion: there is no link between MMR vaccine or thimerosal and autism.

Can vaccines overwhelm my baby’s immune system?

Vaccines cannot overwhelm a baby’s immune system. From the moment they are born babies are exposed to countless germs (bacteria and viruses) every day through their skin, noses, throats and guts. Babies’ immune systems are designed to deal with this constant exposure to new things, learning to recognize and respond to things that are harmful. Even if all the vaccine doses on the schedule were given to a baby all at once, only a small fraction of available immune cells

would be occupied. The immune system is still able to respond to all other threats at any time.

Don’t infants have natural immunity? Isn’t natural immunity better than the kind from vaccines?

Babies may get some temporary immunity (protection) from mom during the last few weeks of pregnancy, but only for diseases to which mom is immune. Breastfeeding may also protect your baby temporarily from minor infections, like colds. These antibodies do not last long, leaving your baby vulnerable to disease.

Natural immunity occurs when your child is exposed to a disease and becomes infected. It is true that natural immunity usually results in better immunity than vaccination, but the risks are much greater. A natural chickenpox infection may result in pneumonia, whereas the vaccine might only cause a sore arm for a couple of days.

Wouldn’t it be safer to vaccinate babies when they are older?

Vaccines are given as soon as it is safe to give them. Babies and young children are most vulnerable to infections when they are very young. In order to protect babies from diseases, they need to be vaccinated before they come into contact with the diseases. Delaying vaccination would leave babies and young children in danger of catching diseases for longer. Babies need the protection vaccines can give them as soon as possible.

Why are so many doses needed for each vaccine?

Getting every recommended dose of each vaccine provides your child with the best protection possible. Depending on the vaccine, your child will need more than one dose to build high enough immunity to prevent disease or to boost immunity that fades over time. Your child may also receive more than one dose to make sure they are protected if they did not get immunity from a first dose, or to protect them against germs that change over time, like flu. Every dose is important because each protects against infectious diseases that can be especially serious for infants and very young children.

Why do vaccines start so early?

The recommended schedule protects infants and children by providing immunity early in life, before they come into contact with life-threatening diseases. Children receive immunization early because they are susceptible to diseases at a young age. The consequences of these diseases can be very serious, even life-threatening, for infants and young children.

What do you think of delaying some vaccines or following a non-standard schedule?

Children do not receive any known benefits from following schedules that delay vaccines. Infants and young children who follow immunization schedules that spread out or leave out shots are at risk of developing diseases during the time you delay their shots. Some vaccine-preventable diseases remain common in the United States and children may be exposed to these diseases during the time they are not protected by vaccines, placing them at risk for a serious case of the disease that might cause hospitalization or death.

Can’t I just wait to vaccinate my baby, since he isn’t in child care, where he could be exposed to diseases?

No, even young children who are cared for at home can be exposed to vaccine preventable diseases, so it’s important for them to get all their vaccines at the recommended ages. Children can catch these illnesses from any number of people or places, including from parents, brothers or sisters, visitors to their home, on playgrounds or even at the grocery store. Regardless of whether or not your baby is cared for outside the home, she comes in contact with people throughout the day, some of whom may be sick but not know it yet.

If someone has a vaccine preventable disease, they may not have symptoms or the symptoms may be mild, and they can end up spreading disease to babies or young children. Remember, many of these diseases can be especially dangerous to young children so it is safest to vaccinate your child at the recommended ages to protect her, whether or not she is in child care.

Can’t I just wait until my child goes to school to catch up on immunizations?

Before entering school, young children can be exposed to vaccine-preventable diseases from parents and other adults, brothers and sisters, on a plane, at child care, or even at the grocery store. Children under age 5 are especially susceptible to diseases because their immune systems have not built up the necessary defenses to fight infection. Don’t wait to protect your baby and risk getting these diseases when he or she needs protection now.

What’s wrong with delaying some of my baby’s vaccines if I’m planning to get them all eventually?

Young children have the highest risk of having a serious case of disease that could cause hospitalization or death. Delaying or spreading out vaccine doses leaves your child unprotected during the time when they need vaccine protection the most. For example, diseases such as Hib or pneumococcus almost always occur in the first 2 years of a baby’s life. And some diseases, like Hepatitis B and whooping cough (pertussis), are more serious when babies get them at a younger age. Vaccinating your child according to the CDC’s recommended immunization schedule means you can help protect him at a young age.

I got the whooping cough and flu vaccines during my pregnancy. Why does my baby need these vaccines too?

The protection (antibodies) you passed to your baby before birth will give him some early protection against whooping cough and flu. However, these antibodies will only give him short-term protection. It is very important for your baby to get vaccines on time so he can start building his own protection against these serious diseases.

Do I have to vaccinate my baby on schedule if I’m breastfeeding him?

Yes, even breastfed babies need to be protected with vaccines at the recommended ages. The immune system is not fully developed at birth, which puts newborns at greater risk for infections.

Breast milk provides important protection from some infections as your baby’s immune system is developing. For example, babies who are breastfed have a lower risk of ear infections, respiratory tract infections, and diarrhea. However, breast milk does not protect children against all diseases. Even in breastfed infants, vaccines are the most effective way to prevent many diseases. Your baby needs the long-term protection that can only come from making sure he receives all his vaccines according to the CDC’s recommended schedule.

Should I get vaccinated if I have allergies?

This depends on the allergy you have. Always ask for medical advice to determine whether you can safely receive vaccinations.

What if I or my child are egg-sensitive?

A number of studies show that most people with anaphylaxis or allergy to eggs can be safely vaccinated.

If you are unsure, ask your doctor.

What if I have a reaction after receiving a vaccination?

It is important to report negative reactions to a vaccination. This gives us a better understanding of the safety of vaccines.

You can report adverse events to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) at https://vaers.hhs.gov/

In general, most children who have had a reaction to a vaccination can be safely re-vaccinated. Immunization specialist services are available in some states. They can advise whether your child needs more testing or precautions before receiving further vaccines. Contact your state or territory health department for details about these services.

What if a family member has had a reaction to an immunization?

Adverse reactions are not hereditary. You should not avoid immunizations because another family member has had a reaction to a vaccine.

What are combination vaccines? Why are they used?

Combination vaccines protect your child against more than one disease with a single shot. They reduce the number of shots and office visits your child would need, which not only saves you time and money, but also is easier on your child.

Some common combination vaccines are Pediarix® which combines DTap, Hep B, and IPV (polio) and ProQuad® which combines MMR and varicella (chickenpox).

Why does my child need a chickenpox shot? Isn’t it a mild disease?

Your child needs a chickenpox vaccine because chickenpox can actually be a serious disease. In many cases, children experience a mild case of chickenpox, but other children may have blisters that become infected. Others may develop pneumonia. There is no way to tell in advance how severe your child’s symptoms will be.

Before vaccine was available, about 50 children died every year from chickenpox, and about 1 in 500 children who got chickenpox was hospitalized.

Who can be immunized?

Most people can be immunized, except for people with certain medical conditions and people who are severely allergic (anaphylactic) to vaccine ingredients.

Certain medical conditions may influence whether you can be immunized. Your ability to be immunized may change when your condition changes.

You should consult your doctor before immunization if you:

- have a fever of more than 101.3 °F (38.5 °C) on the day of your vaccination

- are receiving a medical treatment such as chemotherapy

- have had a bad reaction to a vaccine in the past

- are planning pregnancy, are pregnant or breastfeeding

- are an organ transplant recipient

- have an autoimmune disease or chronic condition.

When do I get immunized?

Your health, age, lifestyle and job will determine the vaccines you need and when to get them.

- Health: Some health conditions may make you more vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases. For example, babies born prematurely, or people who have a weakened immune system may benefit from additional or more frequent immunizations.

- Age: People need protection from different diseases at different ages.

- Lifestyle: Lifestyle choices can have an impact on your immunization needs. You may benefit from immunizations if you are traveling overseas, planning a family, sexually active, a smoker or play sport that may expose you to someone’s blood.

- Occupation: Some jobs may expose you to a greater risk of contact with vaccine-preventable diseases or put you in contact with people who are more susceptible to vaccine-preventable diseases. This includes people working in aged care, childcare, healthcare or emergency service. Find out more about immunization for work.

Vaccines During Pregnancy

Even before becoming pregnant, make sure you are up to date on all your vaccines. This will help protect you and your child from serious diseases. You probably know that when you are pregnant, you share everything with your baby. That means when you get vaccines, you aren’t just protecting yourself—you are giving your baby some early protection too. For example, rubella is a contagious disease that can be very dangerous if you get it while you are pregnant. In fact, it can cause a miscarriage or serious birth defects. The best protection against rubella is MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) vaccine, but if you aren’t up to date, you’ll need it before you get pregnant. Make sure you have a pre-pregnancy blood test to see if you are immune to the disease. Most women were vaccinated as children with the MMR vaccine, but you should confirm this with your doctor. If you need to get vaccinated for rubella, you should avoid becoming pregnant until one month after receiving the MMR vaccine and, ideally, not until your immunity is confirmed by a blood test. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends you get a whooping cough and flu vaccine during each pregnancy to help protect yourself and your baby 9.

Vaccines for Travel: If you are pregnant and planning international travel, you should talk to your doctor at least 4 to 6 weeks before your trip to discuss any special precautions or vaccines that you may need.

Hepatitis B: A baby whose mother has hepatitis B is at highest risk for becoming infected with hepatitis B during delivery. Talk to your healthcare professional about getting tested for hepatitis B and whether or not you should get vaccinated.

Additional Vaccines: Some women may need other vaccines before, during, or after they become pregnant. For example, if you have a history of chronic liver disease, your doctor may recommend the hepatitis A vaccine. If you work in a lab, or if you are traveling to a country where you may be exposed to meningococcal disease, your doctor may recommend the meningococcal vaccine.

Vaccinations before pregnancy

Measles, mumps and rubella

Rubella infection during pregnancy can cause serious birth defects. If you were born after 1966, you may need a booster vaccination for full protection. This should be done in consultation with your doctor. It is recommended that you wait four weeks after receiving this vaccine before trying to get pregnant.

Chickenpox (varicella)

Chickenpox infection during pregnancy can cause severe illness in you and your unborn baby. A simple blood test can determine if you have immunity to this infection. If you are not protected, speak to your doctor about receiving two doses of the vaccine for full immunity. It is recommended that you wait four weeks after receiving this vaccine before trying to get pregnant.

Pneumococcal

Protection against serious illness caused by pneumococcal disease is recommended for smokers and people with chronic heart, lung or kidney disease, or diabetes.

Travel vaccinations

Vaccines that are required to travel to other countries are not always recommended during pregnancy. Find out more about travel and pregnancy.

Safe vaccinations during pregnancy

Influenza and pertussis vaccines are the only vaccines recommended for women during pregnancy.

Whooping cough (pertussis)