What is ERCP

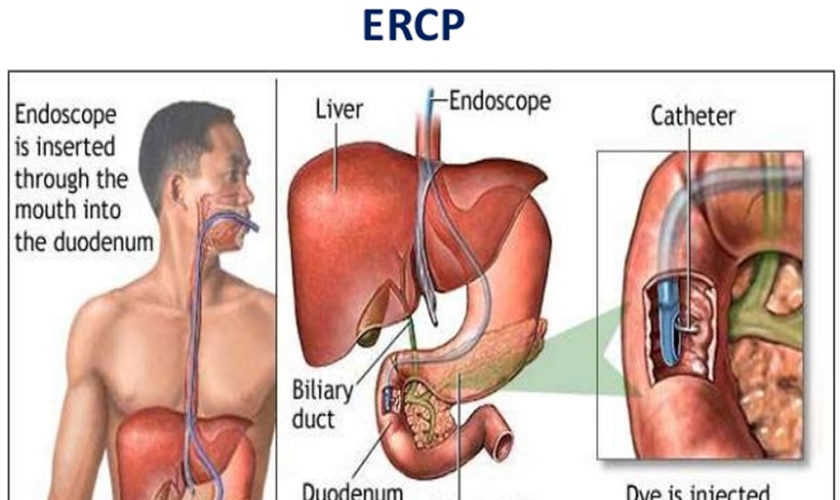

ERCP is an abbreviation for a medical procedure called Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography that combines upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and x-rays to to study the bile ducts, pancreatic duct and gallbladder and to treat problems of the bile and pancreatic ducts. ERCP is an advanced endoscopic procedure where a long, thin flexible tube with a camera at the end called the endoscope is passed through your mouth, esophagus and stomach into the duodenum (first part of the small intestine) down to where the bile and pancreatic duct opens into the small intestine. After your doctor sees the common opening to the ducts from the liver and pancreas, called the major duodenal papilla, your doctor will pass a narrow plastic tube called a catheter through the endoscope and into the ducts. Your doctor will inject a contrast material (dye) into the pancreatic or biliary ducts and will take X-rays.

ERCP procedure most often takes between 1 and 2 hours.

What are the bile and pancreatic ducts?

Your bile ducts are tubes that carry bile from your liver to your gallbladder and duodenum (see Figures 1 to 3). Your pancreatic ducts are tubes that carry pancreatic juice from your pancreas to your duodenum. Small pancreatic ducts empty into the main pancreatic duct. Your common bile duct and main pancreatic duct join before emptying into your duodenum (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Gallbladder location

Figure 2. Gallbladder anatomy

Figure 3. The common bile duct is closely associated with the pancreatic duct and the duodenum

Figure 5. ERCP suite

ERCP indications

Doctors use ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) to treat problems of the bile and pancreatic ducts. Doctors also use ERCP to diagnose problems of the bile and pancreatic ducts if they expect to treat problems during the procedure. For diagnosis alone, doctors may use noninvasive tests—tests that do not physically enter the body—instead of ERCP. Noninvasive tests such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)—a type of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) —are safer and can also diagnose many problems of the bile and pancreatic ducts.

Doctors perform ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) when your bile or pancreatic ducts have become narrowed or blocked because of:

- gallstones that form in your gallbladder and become stuck in your common bile duct

- infection

- acute pancreatitis

- chronic pancreatitis

- trauma or surgical complications in your bile or pancreatic ducts

- pancreatic pseudocysts

- tumors or cancers of the bile ducts

- tumors or cancers of the pancreas

How do I prepare for ERCP?

To prepare for ERCP, talk with your doctor, arrange for a ride home, and follow your doctor’s instructions.

Talk with your doctor

You should talk with your doctor about any allergies you have to medications or to intravenous contrast material (dye). Although an allergy doesn’t prevent you from having ERCP, it’s important to discuss it with your doctor prior to the procedure, as you may require specific allergy medications before the ERCP. Inform your doctor about medications you’re taking (all prescribed and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins, and supplements you take), particularly aspirin products, arthritis medications, anticoagulants (blood thinners, such as warfarin or heparin), clopidogrel or insulin. Also, be sure to tell your doctor if you have heart or lung conditions or other major diseases which might prevent or impact the decision to conduct endoscopy.

Medications list you’ll need to tell your doctor before having ERCP:

- arthritis medicines

- aspirin or medicines that contain aspirin

- blood thinners

- blood pressure medicines

- diabetes medicines

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and naproxen

Your doctor may ask you to temporarily stop taking medicines that affect blood clotting or interact with sedatives. You typically receive sedatives during ERCP to help you relax and stay comfortable.

Tell your doctor if you are, or may be, pregnant. If you are pregnant and need ERCP to treat a problem, the doctor performing the procedure may make changes to protect the fetus from x-rays. Research has found that ERCP is generally safe during pregnancy 1.

Arrange for a ride home

For safety reasons, you can’t drive for 24 hours after ERCP, as the sedatives or anesthesia used during the procedure needs time to wear off. You will need to make plans for getting a ride home after ERCP.

Don’t eat, drink, smoke, or chew gum

To see your upper GI tract clearly, you doctor will most likely ask you not to eat, drink, smoke, or chew gum for at least six hours (and preferably overnight) before the ERCP procedure to make sure you have an empty stomach, which is necessary for the best examination. Your doctor will give you precise instructions about how to prepare.

How is ERCP performed?

Doctors who have specialized training in ERCP perform this procedure at a hospital or an outpatient center. An intravenous (IV) needle will be placed in your arm to provide a sedative. Sedatives help you stay relaxed and comfortable during the procedure. A health care professional will give you a liquid anesthetic to gargle or will spray anesthetic on the back of your throat. The anesthetic numbs your throat and helps prevent gagging during the procedure. The health care staff will monitor your vital signs and keep you as comfortable as possible. Some patients also receive antibiotics before the procedure. In some cases, you may receive general anesthesia.

You’ll be asked to lie on your abdomen on a X-ray table. The doctor will carefully feed the endoscope down your esophagus, through your stomach, and into your duodenum. A small camera mounted on the endoscope will send a video image to a monitor. The endoscope pumps air into your stomach and duodenum, making them easier to see. The ERCP instrument does not interfere with breathing, but you might feel a bloating sensation because of the air introduced through the instrument.

During ERCP, the doctor:

- locates the opening where the bile and pancreatic ducts empty into the duodenum

- slides a thin, flexible tube called a catheter through the endoscope and into the ducts

- injects a special dye, also called contrast medium, into the ducts through the catheter to make the ducts more visible on x-rays

- uses a type of x-ray imaging, called fluoroscopy, to examine the ducts and look for narrowed areas or blockages (see Figure 5 below)

The doctor may pass tiny tools through the endoscope to:

- open blocked or narrowed ducts.

- break up or remove stones.

- perform a biopsy or remove tumors in the ducts.

- insert stents—tiny tubes that a doctor leaves in narrowed ducts to hold them open. A doctor may also insert temporary stents to stop bile leaks that can occur after gallbladder surgery.

Figure 6. ERCP showing multiple gallstones – Note: multiple filling defects with the common bile duct in keeping with choledocholithiasis.

Figure 7. ERCP showing stricture at the bifurcation of the hepatic duct, which was suggestive of a cholangiocarcinoma of the common hepatic duct. The final diagnosis was inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the biliary tree.

ERCP complications

ERCP is a well-tolerated procedure when performed by doctors who are specially trained and experienced in the technique. Although complications requiring hospitalization can occur, they are uncommon. The overall ERCP complication rate requiring hospitalization is 6-10%.

Depending on your age, your other medical problems, what therapy is performed, and the indication for your procedure, your complication rate may be higher or lower than the average. Your doctor will discuss your likelihood of complications before you undergo the test.

Risks vary, depending on why the test is performed, what is found during the procedure, what therapeutic intervention is undertaken, and whether a patient has major medical problems. Patients undergoing therapeutic ERCP, such as for stone removal, face a higher risk of complications than patients undergoing diagnostic ERCP. Your doctor will discuss your likelihood of complications before you undergo the test.

The risks of ERCP include complications such as the following:

- pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas)

- infection of the bile ducts or gallbladder

- excessive bleeding, called hemorrhage

- an abnormal reaction to the sedative, including respiratory or cardiac problems

- perforation in the bile or pancreatic ducts, or in the duodenum near the opening where the bile and pancreatic ducts empty into it

- tissue damage from x-ray exposure

- death, although this complication is rare

- sometimes the procedure cannot be completed for technical reasons.

Research has found that these complications occur in about 5 to 10 percent of ERCP procedures 2. People with complications often need treatment at a hospital.

Seek care right away

If you have any of the following symptoms after ERCP, seek medical attention right away:

- bloody or black, tar-colored stool

- chest pain

- fever

- pain in your abdomen that gets worse

- problems breathing

- problems swallowing or throat pain that gets worse

- vomiting—particularly if your vomit is bloody or looks like coffee grounds

What is a therapeutic ERCP?

ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) is a study of the ducts that drain the liver and pancreas. Ducts are drainage routes into the bowel. The ones that drain the liver and gallbladder are called bile or biliary ducts. The one that drains the pancreas is called the pancreatic duct. The bile and pancreatic ducts join together just before they drain into the upper bowel, about 3 inches from the stomach. The drainage opening is called the papilla. The papilla is surrounded by a circular muscle, called the sphincter of Oddi.

Diagnostic ERCP is when X-ray contrast dye is injected into the bile duct, the pancreatic duct, or both. This contrast dye is squirted through a small tube called a catheter that fits through the ERCP endoscope. X-rays are taken during ERCP to get pictures of these ducts. That is called diagnostic ERCP. However, most ERCPs are actually done for treatment and not just picture taking. When an ERCP is done to allow treatment, it is called therapeutic ERCP.

What treatments can be done through an ERCP scope?

Sphincterotomy

Sphincterotomy is cutting the muscle that surrounds the opening of the ducts, or the papilla. This cut is made to enlarge the opening. The cut is made while your doctor looks through the ERCP scope at the papilla, or duct opening. A small wire on a specialized catheter uses electric current to cut the tissue. A sphincterotomy does not cause discomfort, you do not have nerve endings there. The actual cut is quite small, usually less than a 1/2 inch. This small cut, or sphincterotomy, allows various treatments in the ducts. Most commonly the cut is directed towards the bile duct, called a biliary sphincterotomy. Occasionally, the cutting is directed towards the pancreatic duct, depending on the type of treatment you need.

Stone Removal

The most common treatment through an ERCP scope is removal of bile duct stones. These stones may have formed in the gallbladder and traveled into the bile duct or may form in the duct itself years after your gallbladder has been removed. After a sphincterotomy is performed to enlarge the opening of the bile duct, stones can be pulled from the duct into the bowel. A variety of balloons and baskets attached to specialized catheters can be passed through the ERCP scope into the ducts allowing stone removal. Very large stones may require crushing in the duct with a specialized basket so the fragments can be pulled out through the sphincterotomy.

Stent Placement

Stents are placed into the bile or pancreatic ducts to bypass strictures, or narrowed parts of the duct. These narrowed areas of the bile or pancreatic duct are due to scar tissue or tumors that cause blockage of normal duct drainage. There are two types of stents that are commonly used. The first is made of plastic and looks like a small straw. A plastic stent can be pushed through the ERCP scope into a blocked duct to allow normal drainage. The second type of stent is made of metal wires that looks like the cross wires of a fence. The metal stent is flexible and springs open to a larger diameter than plastic stents. Both plastic and metal stents tend to clog up after several months and you may require another ERCP to place a new stent. Metal stents are permanent while plastic stents are easily removed at a repeat procedure. Your doctor will choose the best type of stent for your problem.

Balloon Dilation

There are ERCP catheters fitted with dilating balloons that can be placed across a narrowed area or stricture. The balloon is then inflated to stretch out the narrowing. Dilation with balloons is often performed when the cause of the narrowing is benign (not a cancer). After balloon dilation, a temporary stent may be placed for a few months to help maintain the dilation.

Tissue Sampling

One procedure that is commonly performed through the ERCP scope is to take samples of tissue from the papilla or from the bile or pancreatic ducts. There are several different sampling techniques although the most common is to brush the area with subsequent examination of the cells obtained. Tissue samples can help decide if a stricture, or narrowing, is due to a cancer. If the sample is positive for cancer it is very accurate. Unfortunately, a tissue sampling that does not show cancer may not be accurate.

ERCP recovery

After ERCP, you can expect the following:

- You will most often stay at the hospital or outpatient center for 1 to 2 hours after the procedure so the sedation or anesthesia can wear off. In some cases, you may need to stay overnight in the hospital after ERCP.

- You may have bloating or nausea for a short time after the procedure.

- You may have a sore throat for 1 to 2 days.

- You can go back to a normal diet once your swallowing has returned to normal.

- You should rest at home for the remainder of the day.

- You should not drive a car for the rest of the day although most patients can return to full activity the next day.

Following the procedure, you—or a friend or family member who is with you if you’re still groggy—will receive instructions on how to care for yourself after the procedure. You should follow all instructions.

Some results from ERCP are available right away after the procedure. After the sedative has worn off, the doctor will share results with you or, if you choose, with your friend or family member.

If the doctor performed a biopsy, a pathologist will examine the biopsy tissue. Biopsy results take a few days or longer to come back.

References- ASGE Standard of Practice Committee, Shergill AK, Ben-Menachem T, et al. Guidelines for endoscopy in pregnant and lactating women. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;76(1):18–24.

- Szary NM, Al-Kawas FH. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: how to avoid and manage them. Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;9(8):496–504.